Abstract

Background:

Parent empowerment is often an expressed goal in clinical pediatrics and in pediatric research, but the antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment are not well established.

Objective:

To synthesize potential antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment in health care settings.

Eligibility criteria:

Inclusion criteria: 1) studies with results about parent empowerment in the context of children’s health care or health care providers; and 2) qualitative studies, observational studies, systematic reviews of such studies.

Information sources:

PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (2006–2016) and reference lists.

Included studies:

Forty-four articles met inclusion criteria.

Synthesis of results:

We identified six themes within consequences of empowerment: increased parent involvement in daily care, improved symptom management, enhanced informational needs and tools, increased involvement in care decisions, increased advocacy for child, and engagement in empowering others. Six themes summarizing antecedents of empowerment also emerged: parent-provider relationships, processes of care, experiences with medical care, experiences with community services, receiving informational/emotional support, and building personal capacity and narrative. We synthesized these findings into a conceptual model to guide future intervention development and evaluation.

Strengths and Limitations of evidence:

Non-English articles were excluded.

Interpretation:

Parent empowerment may enhance parent involvement in daily care and care decisions, improve child symptoms, enhance informational needs and skills, , and increase advocacy and altruistic behaviors. Parent empowerment may be promoted by parent-provider relationship and care processes, finding the right fit of medical and community services, and attention to cognitive and emotional needs of parents.

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines patient empowerment as “a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health [1].” In the context of pediatric health care, parents and caregivers are often the target of efforts to promote empowerment, given their integral role in the care of children. Building on the WHO definition for patient empowerment, parent empowerment can be defined as the process through which parents are able to increase the control they have over decisions and actions affecting their child’s health. Notably, parent empowerment relates to several other topics receiving growing attention in recent years, such as family-centered care [2, 3], shared decision-making [4, 5], and family engagement [6]. These, in addition to parent empowerment, reflect the underlying goal of “the patient as the source of control” recognized by the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) as a guiding force in transitioning to improved systems of health care [7]. Parents navigating the health care system, particularly on behalf of children with chronic illness, may be less likely to perceive an internal locus of control, [8], making attention to empowerment among these families particularly relevant.

Despite its perceived desirability and inherent face-value, the current literature lacks a recent synthesis or an overarching model of the factors that act as antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment. A conceptual model is necessary to guide comprehensive intervention development and to support systematic intervention evaluation. To fill this gap, we sought to synthesize available literature regarding current knowledge of antecedents (i.e. strategies that may result in parent empowerment) and consequences of parent empowerment in the pediatric health care setting.

Specifically, we performed a systematic review to examine (1) proposed consequences and (2) proposed antecedents of parent empowerment in the pediatric health care setting. Because most identified studies on parent empowerment were qualitative, we then performed a narrative synthesis of these studies to best represent their findings. The goal of this systematic review was to develop a hypothesis-generating conceptual model of antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment to guide the evaluation of the impact of empowerment-promoting interventions on health outcomes and to inform strategies to increase parent empowerment.

2. METHODS

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify and extract existing knowledge about parent empowerment in pediatric health care settings. Through narrative synthesis of results from identified publications, we developed a hypothesis-generating conceptual model. A narrative synthesis is the preferred method when heterogeneity in methodology exists across studies [9] and allows identification of descriptive themes [10]. We then further refined the conceptual model by reviewing results and soliciting feedback from parent and provider stakeholders. We focused our review on two primary questions:

For parents navigating the pediatric health care system, what consequences (e.g., functional status, utilization, family burden, parent experience) may be realized by parents experiencing empowerment compared to parents who do not achieve empowerment?

Among parents navigating the pediatric health care system, what factors (i.e., antecedents) may have supported their empowerment compared to parents not achieving empowerment?

We structured our review in this order (i.e., consequences, then antecedents) because identifying consequences of parent empowerment is needed first to determine the value of identifying antecedents. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO (protocol number 2017:CRD42017059478) after the initial search while defining inclusion and exclusion criteria and prior to review of the articles. For this study, we used a working definition of parent empowerment building on the WHO definition of patient empowerment: the process through which parents are able to increase control over decisions and actions affecting their child’s health.

2.1. Search Strategy

We searched PubMed and Web of Science from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2016, with an updated search to incorporate relevant studies from 2017, using search terms related to parents/caregiver (e.g., mother, father, caregiver, parent), empowerment (e.g., empowerment, advocacy), and pediatric/child (e.g., child, pediatric) including additional derivatives. See Appendix Table 1 for the full search string, which was crafted to focus specifically on conceptualizations of empowerment. We also searched Google Scholar and reviewed the reference lists of identified studies. We focused on articles since 2006 to capture the last decade of conceptualizations of parent empowerment, given the evolving understanding of the role of patients and families in health care and the increasing focus on family-centered care, shared decision-making, and family engagement [2–6].

2.2. Selection Criteria

Peer-reviewed research articles were eligible for inclusion if they discussed parent empowerment in the context of the child’s health care or health care providers. We excluded studies that were not either primary studies or structured reviews (e.g. systematic reviews, narrative reviews, or thematic reviews) as well as studies that did not address parent empowerment within the results section of the study. We excluded articles focused only on child/patient empowerment and articles focused entirely on settings and outcomes outside of the health care setting (e.g., education), but did include studies spanning multiple settings if they addressed health care delivery, health care providers, or health care utilization in some capacity. We also excluded studies that were not available in English.

To broadly capture a full range of hypothesized conceptual relationships, we included qualitative studies (including focus groups and interview studies), observational analyses, and systematic reviews of qualitative or observational studies. We excluded intervention studies from this analysis because we could not find an existing framework to use to evaluate the components of these interventional studies. Given this, we instead focused on qualitative and observational studies to develop the needed conceptual model of antecedents and consequences of empowerment, which could be used in turn to deconstruct the components of interventions targeting empowerment (i.e., antecedents), and their impact (i.e., consequences).

2.3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (LEA and KNR) reviewed titles and abstracts independently in duplicate, and excluded studies not meeting inclusion criteria. We reviewed and discussed discrepancies until reaching consensus. All remaining articles were then read in full by one reviewer (LEA) and extracted methodically using structured data extraction forms with both closed- and open-ended fields. A second reviewer (KNR) reviewed 20% of these articles (42/151), after which inclusion/exclusion decisions and data extraction were compared, with substantial consensus noted and discrepancies addressed through iterative discussion. From the articles, we extracted study characteristics as well as the study’s definition of empowerment (if present). We did not formally evaluate the quality or biases of individual qualitative studies, in keeping with current expert recommendations which note the problematic nature of such evaluations in qualitative evidence syntheses [11]. Focusing on reported results of each study, we extracted reported consequences of empowerment (e.g., what happens because of being empowered or disempowered) and reported antecedents of empowerment (e.g., what contributes to and/or deters from being empowered).

2.4. Data Synthesis and Stakeholder Review

We applied narrative synthesis techniques of extracting, grouping, and identifying themes. We synthesized results to identify major themes among (1) consequences of empowerment and (2) antecedents of empowerment. From these themes, we iteratively developed a conceptual model.

To refine the model, we sought iterative input from a stakeholder group of two parents, three physicians, and one hospital administrator to incorporate a range of experiences to guide interpretation and synthesis of findings. This six-member group was convened prior to the current study using best practices for engaging stakeholders as collaborators with the goal of guiding and informing research on pediatric care delivery [12]. The need for the current study was identified through prior work with this group [13]. Stakeholders assisted with reviewing definitions of empowerment, and also reviewed and suggested modifications to groupings of themes and the evolving conceptual model at multiple stages of analysis through group discussion and follow-up one-on-one discussions and emails.

3. RESULTS

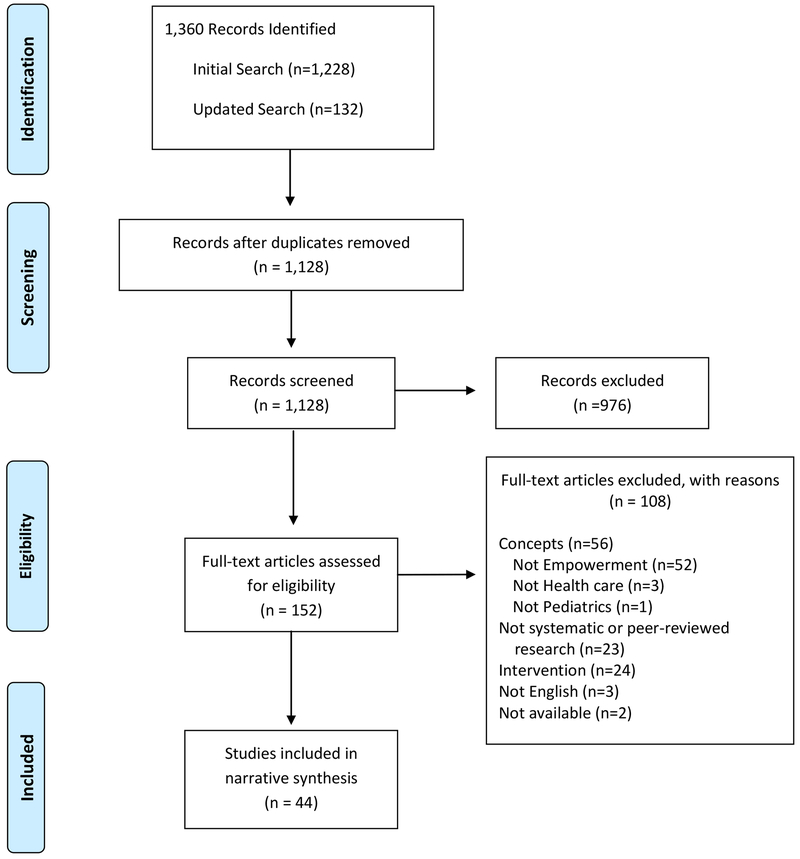

The search resulted in 1,128 unique articles (Figure 1). After initial title and abstract review, 976 were excluded, leaving 152 articles for full review. Many articles excluded during this initial review used “empower” in a non-specific way to discuss implication of their research findings (e.g., suggesting that their study’s findings will empower parents or providers), with no actual focus on the construct of “empowerment.” Of the remaining 152, 56 did not address the topic of interest in their results, including not addressing empowerment (n=52), health care (n=3), or pediatrics (n=1). Twenty-three articles were excluded because they did not include results generated through research methods (e.g. personal narrative/memoir: n=18), were not available in English (n=3) or the full text was not available (n=2). Intervention studies were excluded (n=24) for the reasons noted previously.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram illustrating articles included and excluded in this systematic review and narrative synthesis.

The 44 remaining articles were included. Study characteristics are in Appendix Table 2. The majority were qualitative, employing interview or focus group methods (n=29), representing a total of 687 participants across qualitative studies, with three studies not reporting participant numbers. An additional 10 studies were observational (primarily cross-sectional) with a total of 2,135 participants. Remaining articles were review articles (n=4) and an analysis of discussion board comments (n=1). Most studies included children with special health care needs. Included articles originated the United States (n=22), Canada (n=5), Australia (n=4), Ireland (n=2) and Japan (n=2), with the remaining articles from nine unique countries.

3.1. Definition of Empowerment

The majority of articles (n=32) did not include a formal definition of empowerment. Among those that did, recurrent elements of the definition include acquisition of skills and/or knowledge leading to increased confidence and control interacting with and ultimately navigating the health care environment [14–21]. Often, empowerment was defined, at least in part, by anticipated outcomes such as involvement in decision making [17, 22, 23], providing care [15, 24], and service delivery [21].

3.2. Consequences

The consequences of parent empowerment (or disempowerment), discussed in 29 articles, were synthesized into six themes: (1) involvement or engagement in daily care, (2) symptom management, (3) enhanced informational needs and tools, (4) involvement in care decisions, (5) advocacy for child/family, and (6) empowering others (Table 1).

Table 1:

Consequences of Parent Empowerment

| Consequences of empowerment: why does empowerment matter? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Consequence category | Consequence due to empowerment | Consequence due to lack of empowerment |

| Involvement/Engagement in Daily Care | ||

| Symptom Management | ||

| Enhanced informational Needs and Tools | ||

| Involvement in Care Decisions | ||

| Advocacy for child/family |

|

|

| Empowering others | ||

3.2.1. Involvement or Engagement in Daily Care

Across studies, concepts related to increased involvement or engagement in daily care among empowered parents included enhanced parent belief in their own ability to gain needed skills [25] and achieving mastery of these skills [26]. Other studies suggested that empowerment increased parents engaging in daily care [16, 19, 27, 28], tending to the child’s safety needs [26], desiring increased involvement in treatment [20], and helping the child towards self-management [29].

3.2.2. Symptom Management

Improved symptom management was suggested through reports of empowered parents actively seeking to reduce exposure to triggers (e.g. environmental factors which may result in an increase in disease symptoms) [30] and through the observation of decreased parent-reported symptom burden for children in families with higher empowerment [15]. Despite discussion of reduced symptom burden, we did not find discussion of reduced emergency department visits or hospitalizations.

3.2.3. Enhanced Information Needs and Tools

Enhanced informational needs and tools were indicated through enhanced ability to find information and support [25], actively seeking medical and educational resources [31], and changes in the types of informational needs/priorities of parents [20], including self-education on rights and responsibilities [32]. These heightened informational needs and increased skills suggest increased capacity and skill for engaging with the health care system, while also increasing confidence in the ability to manage and parent in a broader sense [28].

3.2.4. Involvement in Care Decisions

Increased involvement in care decisions was reflected in an increased desire [20], increased confidence [26], or increased perceived control [26] in participating in decisions and partnering in their child’s care [33]. Such decisions may ultimately manifest in receiving fewer services [21]. Actively setting goals for the future [16] was also noted. In contrast, parent disempowerment was associated with loss of choice in care decisions [17] and decreased ability to raise concerns [34].

3.2.5. Advocacy for Child/Family

Additional studies suggested that parent empowerment resulted in increasingly speaking out in the child’s interest. This included advocating for one’s family, advocating for the care for their child, or advocating for themselves as parents [18, 25, 32, 35, 21],. In contrast, one study suggested that parents who are disempowered may need additional help communicating with others [36]. Further, one study suggested empowered parents may stand-up for their child when facing discrimination, whereas disempowered parents may not respond [35].

3.2.6. Empowering Others

Finally, empowered parents may work to empower others [25, 37, 38]. Specifically, one study reported empowered mothers sharing their experiences in hopes of empowering other mothers in similar situations [39].

Overall, these six clusters of consequences vary in immediacy of impact, from a focus on daily care and symptom management to long-term decision-making and planning and striving to improve circumstances for the child and beyond.

3.3. Antecedents

The antecedents of parent empowerment (or disempowerment), discussed in 23 articles, were synthesized into twenty subthemes representing six major themes (Table 2).

Table 2:

Antecedents of Parent Empowerment

| Antecedents of Empowerment: How do we promote empowerment? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Antecedents → Empowerment | Lack of Antecedent/Barrier → Disempowerment |

| PARENT-PROVIDER RELATIONSHIP | ||

| Communication/Being Heard | ||

| Trust | ||

| Continuity of care |

|

|

| Equal member of team |

|

|

| CARE PROCESSES | ||

| Shared decision making | ||

| Shared Goals |

|

|

| Family-centered Care |

|

|

| ALIGNMENT OF CURRENT MEDICAL CARE WITH NEEDS | ||

| Right-fit care/Meeting medical needs | ||

| Medical care in the home | ||

| Symptom Management |

|

|

| ALIGNMENT OF CURRENT COMMUNITY SERVICES WITH NEEDS | ||

| Access to community services | ||

| RECEIVING INFORMATIONAL AND EMOTIONAL SUPPORT | ||

| Receiving information/education | ||

| Being supported in providing daily care/therapy | ||

| Receiving emotional support | ||

| Receiving Peer Support |

|

|

| BUILDING PERSONAL CAPACITY AND NARRATIVE | ||

| Processing the Journey/Narrative Development | ||

| Redefining parenthood/new normal | ||

| Having perceived Influence |

|

|

| Building coping strategies |

|

|

| Develop identify/role as advocate | ||

3.3.1. Parent-Provider Relationship

The parent-provider relationship comprised four subthemes, including attentive communication and being heard [20, 25, 40], trust between the parent and provider [26], continuity of care [26], and family perception of being an equal team member [40, 41]. In contrast, interactions with providers who are insensitive to family preferences [25] or lack of communication with the family overall [42] may lead to disempowerment.

3.3.2. Care Processes

Closely related to the parent-provider relationship, specific processes of care were often discussed as antecedents of empowerment. These included shared decision-making [26, 40, 23, 43], developing shared goals [20, 26, 44], and family-centered care [29]. In contrast, processes leading to disempowerment included parent exclusion from decision-making [41, 43, 45, 25] and discordant expectations and/or goals between parents and providers [26].

3.3.3. Alignment of Current Medical Care with Needs

Articles suggested that finding the health care resource or care setting which best aligns with the medical needs of the child could promote empowerment [24, 21]. A few articles highlighted professional medical care in the home (e.g., home nursing) as an example [25, 45].

3.3.4. Alignment of Current Community Services with Needs

While our search focused on experience with the health care setting, the value of understanding and connecting with community resources was noted as well [43].

3.3.5. Receiving Informational and Emotional Support

Articles frequently discussed the value of parents receiving informational and emotional support. Simply gaining information about their child’s health, diagnosis, and treatment [16, 20, 22, 29, 24, 46, 14] was often discussed as a pathway to empowerment. Lack of information [47], being overwhelmed with information and advice [41], or having unanswered questions [25] were posited as leading to disempowerment. Acquiring the skills and information necessary to provide daily care to the child also emerged as an antecedent of empowerment, including external support for this role [26, 45], and gaining hands-on practice [20, 24, 38, 14]. In addition to these practical skills and cognitive needs, receiving emotional support from providers [16, 25, 26, 48] was frequently mentioned as an antecedent of parent empowerment. Peer support was noted in eight studies as a antecedent of empowerment addressing these informational and emotional needs, ranging from informal parent-to-parent support [16, 49, 24, 22] to more formal peer parent advocates [18, 32, 50, 47]. In contrast, one observational study reported that social support was not significantly associated with family empowerment [36].

3.3.6. Building personal capacity and narrative

In part through these external sources of information and emotional support, several studies discussed an internal evolution toward empowerment as parents process their journey and develop their own narrative. Studies discussed the need for parents to construct a meaningful narrative [51] through self-reflection [45] to facilitate empowerment. Relatedly, many studies described parents arriving at a “new normal” [25, 17] or redefining parenthood [45, 16, 24, 52] in which parents come to accept their reality as a caregiver of a child with a disability or chronic illness. An anchor in developing a personal narrative and accepting the new normal appears to be gaining a sense of perceived influence with the clinical team [23, 43]. In contrast, parents may experience disempowerment through perceived loss of control and certainty [17]. Building coping strategies was identified as another antecedent of empowerment [16, 25, 53, 52]. In contrast, one study noted that parents who feel expected to cope without being given adequate coping skills may be disempowered [25]. Finally, developing an identity as an advocate appeared to promote empowerment [35, 45, 38].

3.4. Contextual Factors

Additionally, nine articles noted contextual factors impacting the process of achieving empowerment. Such factors may include parent, family, and child factors [20]. For example, parent well-being [16], cultural expectations [31], and prior interactions with the health care system [15] may impact the process of empowerment for families. Additional parent factors such as level of education [43], language barriers [15], increased stress [54], mental illness [55], and depressive symptoms [56], and parent’s race [57] may impact the empowerment process. Family factors such as child care arrangements [43], having younger children in the family [43], family financial strain [19], and income [57] were also noted. Finally, child-specific factors such as child behavior issues [55] and medications [52] were further suggested to impact empowerment. Notably, many of these contextual factors may vary over time, such that the degree to which a parent is primed for empowerment in a given health care interaction may vary as well.

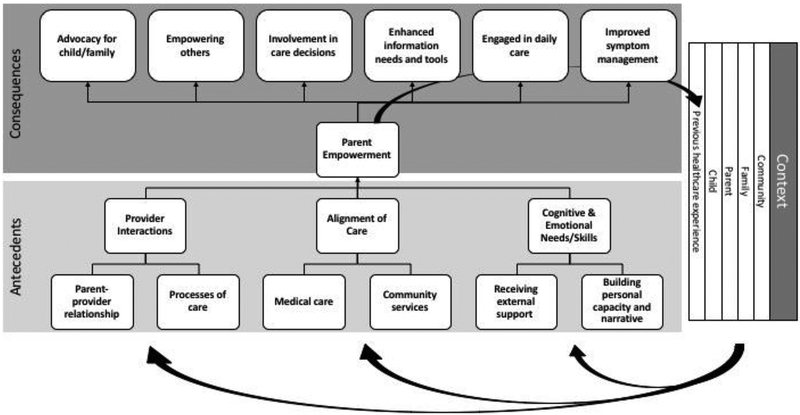

3.5. Conceptual Model

The identified consequences and antecedents of parent empowerment in the pediatric health care setting were further synthesized into a conceptual model and refined through group and one-on-one conversations with stakeholder parents and providers. Group and individual stakeholder discussions emphasized the cyclical nature of empowerment, in which past experiences become a contextual factor impacting the process of empowerment in future interactions. Stakeholder discussions informed iterative grouping of concepts and themes throughout analysis. Stakeholders also described ways that the identified themes and model resonated with their experiences by providing examples from their own lives and experiences.

The model proposed here (Figure 2) illustrates the six major antecedent themes further grouped into provider interactions, alignment of care, and cognitive/emotional support and skills. Provider interactions (e.g., parent-provider relationship and care processes) include the interactions between the clinical team and the parent, child, and family. Alignment of care comprises access and participation in services (e.g., medical and community-based) that align with the needs of the parent and child. Cognitive/emotional support and skills include both the external informational and emotional support received by the parent as well as the personal processing and narrative building by parents over time. Contextual factors, as discussed above, determine the “readiness” for parent empowerment in a given clinical scenario. The model further illustrates that history of achieving empowerment in a prior parent-provider relationship or clinical experience, in turn, contributes to the contextual background that influences how parents approach subsequent interactions with care teams. Thus, empowerment is not a single state to be achieved once, but a dynamic and longitudinal process.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model illustrating the relationship between antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment. Bold curved arrow highlights that prior health care experiences, including prior parent empowerment, become contextual factors influencing current health care experiences and current empowerment.

4. DISCUSSION

We identified six major consequences of parent empowerment, ranging from enhancement of parent involvement in daily care to increased advocacy for the child and the broader community, which were incorporated into a conceptual model. The model offers a comprehensive vision of the antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment, with antecedents broadly divided into interactions with providers, alignment of care, and cognitive and emotional needs.

Parent empowerment is closely aligned with family-centered care, shared decision-making, and family engagement. However, an important distinction from these aforementioned themes emerged through this review, in that parent empowerment uniquely encompasses the parent’s cumulative experiences and skills. The following reviews conceptualizations of parent empowerment as compared to similar themes (i.e. family centered care, shared decision-making, and family engagement) in order to better understand the distinct construct of parent empowerment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) defines patient and family-centered care as “an innovative approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among patients, families, and providers that recognizes the importance of the family in the patient’s life [58].” Core principles include listening to and respecting the patient and family, tailoring services, sharing information, providing formal and informal support, collaborating with families, and recognizing individual strengths of patients and families [58], which broadly overlap with identified antecedents of empowerment: emphasis on the parent-provider relationship, receipt of services that fit the family’s needs, and the need for family support. While family-centered care appears to overlap with antecedents of parent empowerment, consequences for the two constructs diverge. Specifically, compared to consequences identified for family-centered care [2], consequences associated with parent empowerment in our review include more focus on the parent experience and development (e.g., growing as an advocate) and less focus on health care utilization. Additionally, the construct of family-centered care emphasizes the current care experience, whereas the construct of parent empowerment emphasizes the parent’s developmental journey.

Shared decision-making, as a key component of family-centered care, warrants specific attention as it relates to parent empowerment. Shared decision-making is defined as “an interactive process in which patients (families and children, especially more cognitively able children) and physicians (and other involved professionals) simultaneously participate in all phases of the decision-making process and together arrive at a treatment plan to be implemented [5].” Prior work identified barriers and facilitators of shared decision-making that overlap with some of the antecedents (e.g., continuity, power balance) and contexts (e.g., language barriers) [5] of parent empowerment. To date, consequences associated with shared decision-making include more immediate consequences than those discussed for parent empowerment (e.g., reduce decisional conflict, reduce indecision) [5]. In another recent systematic review, the synthesized evidence most robustly indicated that shared decision-making appeared to improve knowledge and reduce decisional conflict [4]. Our synthesis suggests that shared decision-making may be one antecedent of parent empowerment, but that parent empowerment is achieved through a broader set of antecedents and results in a broader set of consequences than shared decision-making alone. In turn, our synthesis suggests that by achieving this broader goal of empowerment, parents may be better prepared to engage in shared decision-making with future providers.

Finally, patient and family engagement include partnerships between families and providers for “improving health, quality, safety, and delivery of health care [6].” In a recent narrative review, patient and family engagement was noted across different studies to improve patient-centered communication, reduce unnecessary health care utilization, improve health status, improve safety, improve satisfaction with communication, and improve family functioning [6], again overlapping with some consequences identified in our literature review (e.g., symptom management), but omitting some (e.g., self-advocacy, evolving informational needs, altruism), and incorporating others not identified (e.g., reduced unnecessary utilization, improved satisfaction). These differences in part help emphasize the distinctiveness of the terms, with family engagement emphasizing the relationship with the health care system, whereas parent empowerment emphasizes the parent’s personal development and evolution. The comparison between family engagement and parent empowerment also highlights the lack of connection between parent empowerment and reduced health care utilization in our synthesized results. This does not necessarily mean that there is no link between parent empowerment and utilization, but rather that this link has not emerged in qualitative analysis or in cross-sectional studies. Qualitative work specifically exploring the link between parent empowerment and health care utilization could be valuable given this gap.

Therefore, parent empowerment is a unique construct that relates to family-centered care, shared decision-making, and family engagement, but with notable differences in the conceptualized antecedents and consequences. Family-centered care appears to summarize the antecedents that lead to empowerment (with shared decision-making being one of these antecedents), and family engagement is a state that families may achieve but is defined more specifically in the family’s relationship with the health care system rather than an internal state achieved by parents. These distinctions are important for those seeking to promote empowerment and for those seeking to assess the impact of empowerment.

An additional point that warrants further discussion is the cyclical conception of empowerment that arose through this synthesis, which first became apparent through our review and was further highlighted by stakeholders. First, we observed that prior health care experiences were identified as a contextual factor that may influence empowerment, suggesting that each experience shapes the likelihood of future empowerment. Understanding these contextual factors as a component of each episode of care is critical in fully promoting empowerment in parents. Without an understanding of the environment within which parents exist - and a recognition that this environment can vary across time and episodes of care -- efforts to increase parent empowerment may not be successful. Future research to understand and tailor interventions based on parent contextual factors may be needed to promote parent empowerment.

Second, we noted that several similar or related concepts were suggested as antecedents and as consequences in different studies. For example, receiving adequate information was often suggested as an antecedent of empowerment, with a related consequence of empowerment being the improved ability to find information and changes in informational needs. As another example, shared decision-making appeared as a potential antecedent of empowerment, and involvement in care decisions was suggested as a consequence. One reason for this relatedness in our synthesis could be due to the nature of the studies - qualitative and observational studies only determine association between concepts with directionality generally inferred. However, another potential explanation, and one suggested by stakeholders, is that prior experiences shape future expectations and interactions. In our conceptual model, the feedback loop highlights this possibility. The cyclical experience is likely more apparent in discussion of the concept of parent empowerment compared to family-centered care, shared decision-making, and family engagement due to the focus on the state of the parent.

4.1. Limitations

The current study is a narrative synthesis of observational work and should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Many of the observational studies synthesized reported associations. When directionality of relationships was not obvious from the empiric findings, we used the interpretation of the original study’s authors in our synthesis. Additionally, we note that among proposed antecedents, prior work does not address whether individual antecedents are either necessary or sufficient to foster parent empowerment. We excluded intervention studies because we lacked a framework to evaluate the components of disparate interventions. With the framework provided in this study, future research should systematically review intervention studies and examine causal relationship between conceptualized antecedents and consequences of parent empowerment. We note that including systematic reviews in addition to primary literature could over-represent findings of specific studies in a quantitative synthesis but is less of a concern in this narrative synthesis, which focused on identifying concepts rather than quantitatively weighting them. An additional limitation is the inconsistent definition, conceptualization, and measurement of parent empowerment in prior work. For example, some studies used the term “empowerment” without providing or referencing an explicit definition, raising the question of the authors’ intent in use of the term. Given this, we performed our search broadly to capture as many relevant studies as possible. We hope that one outcome of this work is increased rigor in future studies operationalizing and assessing parent empowerment. Finally, most studies focused on children with chronic conditions, such that generalizability to other pediatric populations may be limited. Despite these limitations, this study provides a synthesis and conceptualization of parent empowerment, providing a hypothesis-generating framework for synthesis of existing interventional work and for development and evaluation of future interventions.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, through narrative synthesis of 33 studies with iterative stakeholder review, we identified six consequences and six antecedents of parent empowerment, and developed a conceptual model, which acknowledges that strategies to promote parent empowerment should consider the context of specific family circumstances, care teams, and health care situations. Future research should explore which combination or combinations of antecedents lead to parent empowerment while also considering contextual factors, which may vary greatly. The current study provides a foundation for future work to better understand mechanisms by which parents may achieve empowerment and expected outcomes of parent empowerment in the pediatric health care setting.

Supplementary Material

Key Points for Decision Makers.

Parent empowerment may increase parent engagement in daily care, increase parent involvement in care decisions, enhance parent informational needs and tools, improve the child’s symptom management, increase parent ability to advocate for the child and family, and promote engagement in activities that empower others.

Strategies to support parent empowerment may include enhancing parent-provider relationships, family-centered processes of care, aligning the fit of both medical care and community services, providing informational/emotional support, and improving parents’ self-reflection and coping strategies.,

Acknowledgements.

We gratefully acknowledge the time and contribution of our stakeholder group, the Pediatric Care Delivery Consultants, to this work. This study was supported in part by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022989, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institutional Mentored Career Development Award, Dr. Ray) and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC (Dr. Ray). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript

Ms. Ashcraft has no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Asato receives salary support from HRSA # T73MC00036 (LEND Program at the University of Pittsburgh) and NINDS U24NS107166 (Network of Excellence in Neuroscience Clinical Trials - University of Pittsburgh CRS). Medical Advisory for Epilepsy Western Central PA and the Emma Bursick Memorial Foundation

Dr. Houtrow has no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Kavalieratos receives research support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K01HL133466). He has no non-financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Miller has a mid-career development award from the National Institutes of Health, K24HD075862.

Dr. Ray has received research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022989) and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. She has no non-financial conflicts of interest.

LEA and KNR conceptualized the study. LEA, MA, AJH, EM, and KNR contributed to conceptual design, and LEA, DK, and KNR contributed to methodological design. LEA and KNR completed the search, literature review, and data extraction. LEA, MA, AJH, DK, EM, and KNR participated in analysis and interpretation of results. LEA drafted the manuscript and all authors critically revised for important intellectual content. All authors approve the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022989)

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Health Promotion Glossary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhlthau KA, Bloom S, Van Cleave J, Knapp AA, Romm D, Klatka K et al. Evidence for family-centered care for children with special health care needs: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(2):136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Council on Children with D, Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory C. Patient- and family-centered care coordination: a framework for integrating care for children and youth across multiple systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1451–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyatt KD, List B, Brinkman WB, Prutsky Lopez G, Asi N, Erwin P et al. Shared Decision Making in Pediatrics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(6):573–83. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams RC, Levy SE, Council On Children With D. Shared Decision-Making and Children With Disabilities: Pathways to Consensus. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cene CW, Johnson BH, Wells N, Baker B, Davis R, Turchi R. A Narrative Review of Patient and Family Engagement: The “Foundation” of the Medical “Home”. Med Care. 2016;54(7):697–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee on Quality Health Care in America IoM. Crossing the quality chasm : a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, [2001] ©2001; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrin EC, Shapiro E. Health locus of control beliefs of healthy children, children with a chronic physical illness, and their mothers. J Pediatr. 1985;107(4):627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT GSe. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org.

- 12.PCORI. PCORI Engagement Rubric. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/EngagementRubric.pdf. 2015. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf.

- 13.Ray KN, Ashcraft LE, Kahn JM, Mehrotra A, Miller E. Family Perspectives on High-Quality Pediatric Subspecialty Referrals. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(6):594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.05.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis CE, Reid S, Elliott C, Nyquist A, Jahnsen R, Rosenberg M et al. ‘It’s important that we learn too’: Empowering parents to facilitate participation in physical activity for children and youth with disabilities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017:1–14. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1378367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutinho MT, Kopel SJ, Williams B, Dansereau K, Koinis-Mitchell D. Urban caregiver empowerment: Caregiver nativity, child-asthma symptoms, and emergency-department use. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(3):229–39. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson RJ, Johnson A, Moodie S. Parent-to-parent support for parents with children who are deaf or hard of hearing: a conceptual framework. Am J Audiol. 2014;23(4):437–48. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox T Caregivers reflecting on the early days of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis TS, Gavazzi SM, Scheer SD, Uppal R. Measuring Individualized Parent Advocate Services in Children’s Mental Health: A Contextualized Theoretical Application. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;20(5):669–84. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9443-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox GL, Nordquist VM, Billen RM, Savoca EF. Father Involvement and Early Intervention: Effects of Empowerment and Father Role Identity. Family Relations. 2015;64(4):461–75. doi: 10.1111/fare.12156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kruijsen-Terpstra AJ, Verschuren O, Ketelaar M, Riedijk L, Gorter JW, Jongmans MJ et al. Parents’ experiences and needs regarding physical and occupational therapy for their young children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;53–54: 314–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casagrande KA, Ingersoll BR. Service Delivery Outcomes in ASD: Role of Parent Education, Empowerment, and Professional Partnerships. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2017;26(9):2386–95. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0759-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujioka H, Ogasawara A, Okubo Y, Ito M. Empowerment process of mothers rearing children with disabilities in mother and child residential rehabilitation program. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timberlake MT, Leutz WN, Warfield ME, Chiri G. “In the driver’s seat”: Parent perceptions of choice in a participant-directed medicaid waiver program for young children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):903–14. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaughan V, Logan D, Sethna N, Mott S. Parents’ perspective of their journey caring for a child with chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(1):246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewetson R, Singh S. The lived experience of mothers of children with chronic feeding and/or swallowing difficulties. Dysphagia. 2009;24(3):322–32. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panicker L Nurses’ perceptions of parent empowerment in chronic illness. Contemp Nurse. 2013;45(2):210–9. doi: 10.5172/conu.2013.45.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown FL, Whittingham K, Sofronoff K, Boyd RN. Parenting a child with a traumatic brain injury: experiences of parents and health professionals. Brain Inj. 2013;27(13–14):1570–82. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.841996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King G, Schwellnus H, Servais M, Baldwin P. Solution-Focused Coaching in Pediatric Rehabilitation: Investigating Transformative Experiences and Outcomes for Families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017:1–17. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2017.1379457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmbeck GN, Alriksson-Schmidt AI, Bellin MH, Betz C, Devine KA. A family perspective: how this product can inform and empower families of youth with spina bifida. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57(4):919–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellin MH, Land C, Newsome A, Kub J, Mudd SS, Bollinger ME et al. Caregiver perception of asthma management of children in the context of poverty. J Asthma. 2017;54(2):162–72. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1198375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yousafzai AK, Farrukh Z, Khan K. A source of strength and empowerment? An exploration of the influence of disabled children on the lives of their mothers in Karachi, Pakistan. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(12):989–98. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.520811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munson MR, Hussey D, Stormann C, King T. Voices of parent advocates within the systems of care model of service delivery. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31(8):879–84. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gadepalli SK, Canvasser J, Eskenazi Y, Quinn M, Kim JH, Gephart SM. Roles and Experiences of Parents in Necrotizing Enterocolitis: An International Survey of Parental Perspectives of Communication in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. 2017;17(6):489–98. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coyne I, McNamara N, Healy M, Gower C, Sarkar M, McNicholas F. Adolescents’ and parents’ views of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in Ireland. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(8):561–9. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neely-Barnes SL, Graff JC, Roberts RJ, Hall HR, Hankins JS. “It’s our job”: qualitative study of family responses to ableism. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;48(4):245–58. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-48.4.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decker KA, Miller WR, Buelow JM. Parent Perceptions of Family Social Supports in Families With Children With Epilepsy. J Neurosci Nurs. 2016;48(6):336–41. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rafferty KA, Sullivan SL. “You Know the Medicine, I Know My Kid”: How Parents Advocate for Their Children Living With Complex Chronic Conditions. Health Commun. 2017;32(9):1151–60. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1214221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adelsperger S, Prows CA, Myers MF, Perry CL, Chandler A, Holm IA et al. Parental Perception of Self-Empowerment in Pediatric Pharmacogenetic Testing: The Reactions of Parents to the Communication of Actual and Hypothetical CYP2D6 Test Results. Health Commun. 2017;32(9):1104–11. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1214216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan CE. Cybersupport: empowering asthma caregivers. Pediatr Nurs. 2008;34(3):217–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong ST, Lynam MJ, Khan KB, Scott L, Loock C. The social paediatrics initiative: a RICHER model of primary health care for at risk children and their families. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson K, Balandin S, Stancliffe R. Australian parents’ experiences of speech generating device (SGD) service delivery. Dev Neurorehabil. 2014;17(2):75–83. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2013.857735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fixter V, Butler C, Daniels J, Phillips S. A Qualitative Analysis of the Information Needs of Parents of Children with Cystic Fibrosis prior to First Admission. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;34:e29–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vuorenmaa M, Halme N, Perala ML, Kaunonen M, Astedt-Kurki P. Perceived influence, decision-making and access to information in family services as factors of parental empowerment: a cross-sectional study of parents with young children. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(2):290–302. doi: 10.1111/scs.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lotz JD, Daxer M, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Fuhrer M. “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst”: A qualitative interview study on parents’ needs and fears in pediatric advance care planning. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):764–71. doi: 10.1177/0269216316679913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dellenmark-Blom M, Wigert H. Parents’ experiences with neonatal home care following initial care in the neonatal intensive care unit: a phenomenological hermeneutical interview study. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(3):575–86. doi: 10.1111/jan.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konrad SC. What parents of seriously ill children value: parent-to-parent connection and mentorship. Omega (Westport). 2007;55(2):117–30. doi: 10.2190/OM.55.2.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell M, Fitzgerald R, Legge M. Parent peer advocacy, information and refusing disability discourses. Kotuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 2013;8(1–2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan-Bolyai S, Lee MM. Parent mentor perspectives on providing social support to empower parents. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(1):35–43. doi: 10.1177/0145721710392248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeHoff BA, Staten LK, Rodgers RC, Denne SC. The Role of Online Social Support in Supporting and Educating Parents of Young Children With Special Health Care Needs in the United States: A Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(12):e333. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis TS, Scheer SD, Gavazzi SM, Uppal R. Parent advocates in children’s mental health: program implementation processes and considerations. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010;37(6):468–83. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levine KA. Against all odds: resilience in single mothers of children with disabilities. Soc Work Health Care. 2009;48(4):402–19. doi: 10.1080/00981380802605781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wakimizu R, Yamaguchi K, Fujioka H. Family empowerment and quality of life of parents raising children with Developmental Disabilities in 78 Japanese families. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2017;4(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gannoni AF, Shute RH. Parental and child perspectives on adaptation to childhood chronic illness: a qualitative study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):39–53. doi: 10.1177/1359104509338432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bode AA, George MW, Weist MD, Stephan SH, Lever N, Youngstrom EA. The Impact of Parent Empowerment in Children’s Mental Health Services on Parenting Stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25(10):3044–55. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0462-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiss JA, Cappadocia MC, MacMullin JA, Viecili M, Lunsky Y. The impact of child problem behaviors of children with ASD on parent mental health: the mediating role of acceptance and empowerment. Autism. 2012;16(3):261–74. doi: 10.1177/1362361311422708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martinez KG, Perez EA, Ramirez R, Canino G, Rand C. The role of caregivers’ depressive symptoms and asthma beliefs on asthma outcomes among low-income Puerto Rican children. J Asthma. 2009;46(2):136–41. doi: 10.1080/02770900802492053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huscroft-D’Angelo J, Trout AL, Lambert MC, Thompson R. Caregiver perceptions of empowerment and self-efficacy following youths’ discharge from residential care. Journal of Family Social Work. 2017;20(5):433–56. doi: 10.1080/10522158.2017.1350893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Committee on Hospital Care. American Academy of P. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):691–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.