Abstract

The peptide transmitter N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) and its receptor, the type 3 metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR3, GRM3), are prevalent and widely distributed in the mammalian nervous system. Drugs that inhibit the inactivation of synaptically released NAAG have procognitive activity in object recognition and other behavioral models. These inhibitors also reverse cognitive deficits in animal models of clinical disorders. Antagonists of mGluR3 block these actions and mice that are null mutant for this receptor are insensitive to the actions of these procognitive drugs. A positive allosteric modulator of this receptor also has procognitive activity. While some data suggest that drugs acting on mGluR3 achieve their procognitive action by increasing arousal during acquisition training, exploration of the procognitive efficacy of NAAG is in its early stages and thus substantial opportunities exist to define the breadth and nature of this activity.

Keywords: memory, NAAG, N-acetylaspartylglutamate, metabotropic receptors, mGluR3, glutamate carboxypeptidase II

1.1. Introduction

N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) is the third most prevalent and widely distributed neurotransmitter in the mammalian nervous system (Neale et al., 2005, 2011). Following synaptic release (Figure 1), NAAG is inactivated by a glial enzyme, glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) (Slusher et al., 1990, Bzdega et al., 1997). Among its established functions, NAAG activates the presynaptic type 3 (mGluR3, GRM3) metabotropic glutamate receptor (see Riener and Levitz, 2018 for review of mGluRs) to inhibit subsequent release of its co-transmitters, including glutamate (Zhong et al., 2006, Olszewski et al., 2012b, Zuo et al., 2012, Romei et al., 2013, Nonaka et al., 2017). Inhibitors of GCPII reduce the rate of inactivation of NAAG and elevate the extracellular concentration of this peptide (Zhong et al., 2006, Zuo et al., 2012). These GCPII inhibitors are effective in animal models of inflammatory pain (Nonaka et al., 2017), stroke (Slusher et al., 1999), traumatic brain injury (Zhong et al., 2005, Gao et al., 2015) and schizophrenia (Olszewski et al., 2004, 2008, 2012). In the pain, brain injury and schizophrenia studies, these actions are blocked by the heterotropic group II (mGluR2/3) receptor antagonist LY341495. Drugs that act as heterotropic agonists at these group II receptors have been inconsistent with respect to their procognitive effects (Sato et al., 2004; Spinelli et al., 2005; Daumas et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2010). In contrast, inhibitors of the inactivation of extra-synaptic NAAG elicit procognitive actions in animal models and these actions are blocked by the mGluR2/3 antagonist (Olszewski et al., 2012a; Janczura et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

NAAG as a peptide co-transmitter. In this figure, NAAG is co-released with a primary amine transmitter, such as glutamate, under conditions of elevated neuronal activity. NAAG is released into the perisynaptic space where it activates presynaptic and glial type 3 metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR3). NAAG is inactivated by glutamate carboxypeptidases II (GCPII) and III (GCPIII), forming N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and glutamate (Glu), which are rapidly transported into glial cells. Inhibition of these peptidases by a NAAG peptidase inhibitor, such as ZJ43, reduces inactivation of NAAG and increaases perisynaptic NAAG levels. In animal models, the NAAG peptidase inhibitor-mediated elevation of peptide levels increases the activation of mGluR3 receptors on axon endings, reducing subsequent transmitter release. The consequences of NAAG activation of mGluR3 receptors on glial cells have not been well established beyond the observation that NAAG inhibits adenylate cyclase and stimulates the release of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β).

Figure reproduced with permission: Neale et al., (2011) Journal of Neurochemistry, 118(4), 490-498.

1.2. Procognitive Actions of NAAG via Glutamate Carboxypeptidase Inhibitors

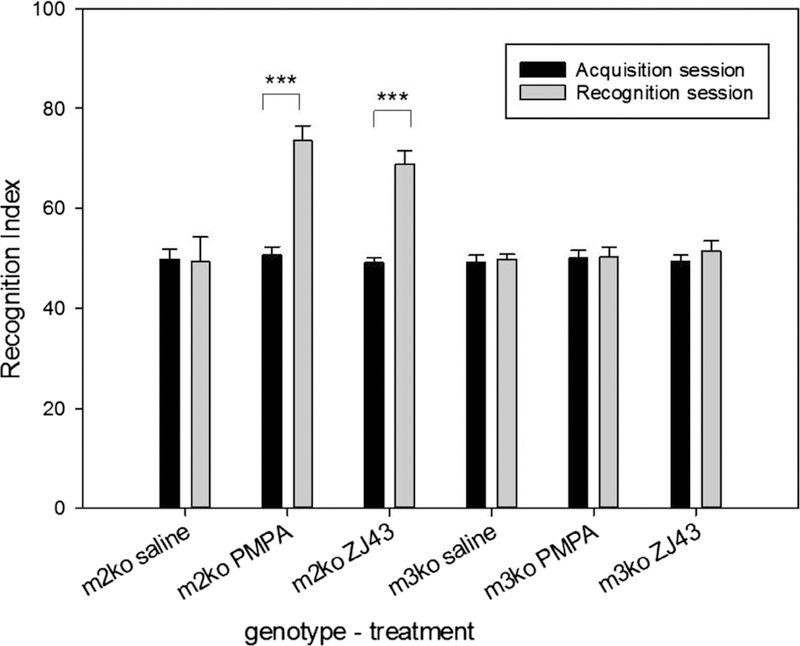

The procognitive effects of NAAG have been assayed using the Novel Object Recognition Test. In this test, mice are presented with two identical objects during the acquisition trial and tested 1.5 hour (short-term memory) or one day (long-term memory) later with one of the original objects and one novel object (Antunes and Biala, 2012). Memory of the original object is determined by the extent to which the mice explore the novel object relative to the familiar object in the retention trial. Mice tested for novel object recognition have substantial short-term recall of the novel object when tested within a few hours of acquisition but lack significant long-term memory of the novel object 24 hours or more later (Antunes, and Biala, 2012). However, treatment of mice with a GCPII inhibitor 15 minutes prior to the acquisition trial results in novel object recognition at the 24 hr test point (Janczura et al., 2013). Similarly, untreated mice in which the GCPII gene had been deleted demonstrate good retention in the long-term novel object recognition while their control colony mates do not (Janczura et al., 2013). The mechanism of action of this procognitive effect was tested in mice that were null mutant for mGluR2 or mGluR3 (Figure 2, Olszewski et al., 2017). Mice lacking mGluR2 responded to GCPII inhibitors (ZJ43 and 2-PMPA) with a significantly increased level of recall after 24 hours while the inhibitor had no procognitive activity in mice lacking mGluR3. Since these inhibitors lacked direct activity at mGluR3 (Olszewski et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2007), these data support the conclusion that this procognitive action of the peptidase inhibitor is mediated via NAAG activation of mGluR3.

Figure 2.

Long-term novel object recognition memory test in mGluR2 and mGluR3 KO mice. During the acquisition session, mice were individually placed in a chamber for 10 minutes with two identical objects and the amount of time exploring each object was recorded. In the recognition session 24 hours after acquisition, mice were returned to the chamber with one of the original objects and a novel object. For the acquisition session, the recognition index (RI) was calculated as [time exploring one of the objects/the time exploring both objects] × 100. For the recognition session, the RI was calculated as [time exploring the novel object/the time exploring both the familiar and novel object] × 100. During the acquisition phase, mice explored each of the two identical objects about the same amount of time (recognition index ~50). During the recognition phase 24 h later, the mGluR2 KO mice (m2ko) treated with saline explored the novel and familiar object similar amounts of time while those treated with 2-PMPA (100 mg/kg) or ZJ43 (150 mg/kg) explored the novel object twice as often as the original object (recognition index ~70). The NAAG peptidase inhibitors had no procognitive effect in the mGluR3 ko mice (m3ko) supporting the conclusion that NAAG acts via mGluR3. ***p < 0.001 for comparison between acquisition session and recognition session within treatment group.

Figure reproduced with permission: Olszewski et al., (2017) Neurochemical Research, 42, 2646–2657,.

While mice typically have substantial short-term novel object recall when tested 1.5 hr. after acquisition (Fahlstrom et al., 2011), this cognitive function is substantially blocked in animal models of schizophrenia and alcohol intoxication. In mice, the open channel NMDA receptor antagonists MK801 and PCP induce schizophrenia-like behaviors including cognitive deficits (Olszewski et al., 2004, 2012a). GCPII inhibitors significantly reduce behaviors induced by these drugs in control mice and in mice lacking mGluR2 but not in mice lacking mGluR3 (Olszewski et al., 2012b) again consistent with the role of NAAG as an mGluR3 agonist. Pretreatment of mice with GCPII inhibitors reverses MK801-induced loss of short-term novel object recognition (Olszewski et al., 2012a). Similarly, GCPII inhibition as well as a heterotropic mGluR/3 agonist restores short-term object recognition in mice treated with intoxicating doses (2.3g/l) of ethanol (Olszewski et al., 2017). In this clinical model, the GCPII inhibitors also moderate the loss of motor coordination.

Triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model mice perform well in short-term novel object recognition at 8 weeks but not at 5 and 9 months of age in contrast to non transgenic colony mates that perform well on this test as late as 22 months of age (Webster et al., 2013). Pretreatment of the 9 month-old Alzheimer’s model mice with a GCPII inhibitor immediately before testing significantly improves short-term novel object recognition (Olszewski et al., 2017).

A GCPII inhibitor also was tested in an EAE model of Multiple Sclerosis (Hollinger et al., 2016). The drug was given daily for two weeks and found to have no significant effects on the degenerative elements of the model. However, the inhibitor treatment did rescue the EAE induced deficits in the Barnes maze test in a dose dependent manner. Since the last dose of the drug was given just before the onset of behavioral testing, it is unclear if its procognitive efficacy was due to the long-term treatment or to the effects of the most proximate dose.

It is possible that GCPII inhibitors acted via different mechanisms in these studies. Their efficacy in increasing long-term memory in control mice and short term memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease model mice might involve increased attention during acquisition trials. Consistent with this, a heterotropic group II agonist increased attention and working memory in monkeys (Spinelli et al., 2005). Alternatively, the inhibitors might act directly on cellular mechanisms underlying short- and long-term memory formation. Given differences in the cellular mechanisms underlying these processes, such as the role of protein synthesis the long-term but not the short term phase of LTP (Allen et al., 2018) and long-term but not short term memory formation (Neale et al., 1973), it would seem unlikely that one drug would act directly on the cellular mechanisms underlying both. In the ethanol and schizophrenia models, the GCPII inhibition inhibitors also had positive effects on non-cognitive elements of the models (Olszewski et al., 2004, 2012a, 2017). As a result, it could be that in these studies the inhibitors increased cognition by moderating the mechanisms of action of the drugs that underly these models.

1.3. Group II metabotropic receptor agonists and allosteric modulators

Behavioral studies using heterotropic group II mGluR agonists and antagonists have not provided a consistent picture of the role of these receptors in cognition. The group II antagonist, LY342495, reduced acquisition in the novel object recognition test (Barker et al., 2006). In another study, a high dose of the antagonist reduced performance in the novel object recognition test while a lower dose not affect initial recall but rather decreased extinction of the memory (Pitsikas et al., 2012). Chronic treatment with a group II mGluR antagonist also reduced cognition in a spatial memory test (Altinbilek et al., 2009). Consistent with these studies, the group II agonist, LY379268, reversed social isolation-induced recognition memory deficits (Jones et al., 2010). In contrast: the group II agonist, LY354740, reduced attention and working memory in monkeys (Spinelli et al., 2005); the group II agonist, DCG-IV, and antagonist, LY341495, both impaired memory in a passive avoidance task (Sato et al., 2004); DCG-IV similarly impaired contextual fear memory consolidation when injected into the hippocampus (Daumas et al, 2009).

Data from group II receptor deletion studies support a role for these receptors in cognition. mGluR2 null mutant mice exhibited deficits in the rewarded alternation elevated T-maze test, while mice lacking mGluR3 were impaired initially but improved in the course of the retention test (Bishop et al., 2014, DeFilippis et al., 2014). The deletion of both group II receptors negatively affected a series of appetitively motivated learning paradigms but failed to affect aversely motivated special learning tasks, a result suggesting that the procognitive role of one or both receptors is mediated by increasing attention or arousal during acquisition trials (Lyon et al., 2011). A difficulty in interpreting the data from such gene deletion studies derives from the potential of structurally related receptors to compensate for the loss of each other.

Consistent with data on the efficacy of NAAG/mGluR3 mediated increases in cognition described above, treatment of mice with a mGluR3 selective negative allosteric modulator resulted in impaired learning in a medial prefrontal cortex dependent fear extinction task (Walker et al., 2015). Additional, albeit indirect, support for the involvement of mGluR3 in human cognition comes from studies that established a correlation between polymorphisms in the mGluR3 gene with deficits in cognition as well as with schizophrenia (Egan et al., 2004). Complex pharmacological relationships also have been deduced among polymorphisms in this gene and deficits in cognition and response to antipsychotic drugs (Bishop et al., 2015).

1.4. Mechanisms of Action

Like many peptide transmitters, NAAG appears to be released when neuronal circuits are activated at high levels. One consequence is the activation of presynaptic autoreceptors with the consequent reduction in calcium-dependent transmitter release, a mechanism that would extend the dynamic range of the circuit. That is, as the activity rises within a circuit, the increasing co-release of NAAG gradually dampens the release of the primary transmitter resulting in an expansion of the upper range of circuit activity before the pre- and/or post-synaptic responses reach maximum capacity. Consistent with this model, NAAG-mediated inhibition of transmitter release has been confirmed in vivo in animal models of stroke, traumatic brain injury, inflammatory pain and schizophrenia (Slusher et al., 1990, Zhong et al., 2006, Zuo et al., 2012, Nonaka et al., 2017).

While mGluR3 receptors and heterotropic mGluR2/mGluR3 receptors are found on presynaptic terminals in spinal cord and cortex, respectively (Di Prisco et al., 2016; Olivero et al, 2017), NAAG also could act procognitively via postsynaptic mGluR3 receptors. Data supporting this hypothesis derives from a study in the primate dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a region involved in processing working memory (Jin et al., 2018). In this study, NAAG and a GCPII inhibitor independently stimulated cortical Delay cell firing during a working memory task via inhibition of a cAMP-mediated pathway.

At the cellular level, NAAG activation of mGluR3 results in reduced levels of cAMP and cGMP in neurons and astrocytes (Wroblewska et al., 1998, 2006). Consistent with the role of cAMP in mediating long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus, NAAG blocked long-term potentiation at this synapse via presynaptic mGluR3 activation (Lea et al., 2001; Pöschel et al., 2005). Conversely, a mGluR3 antagonist blocked long-term depression in the dentate gyrus (Pöschel et al., 2005) while a mGluR3 negative allosteric modulator blocked long-term depression in the medial prefrontal cortex (Walker et al., 2015). NAAG also acts as an antagonist at a subset of hippocampal NMDA receptors that are pH dependent (Khacho et al., 2015) while it fails to affect NMDA receptors more broadly (Losi et al., 2004). A role for NAAG at NMDA receptors has not been explored with respect to cognition. Given the positive role of NMDA receptors in plasticity, including LTP, it is difficult to see how antagonism at hippocampal NMDA receptors would mediate a procognitive action.

Considering the breadth of brain circuits involved in attention and object recognition memory together with the widespread distribution of NAAG and mGluR3, dissection of the precise locus of action of the peptide in cognitive processes will be demanding and likely to depend on the model of cognition being tested. From the pharmacological prospective, such analyses will be advanced by the development of mGluR3 selective agonists and antagonists and yet be complicated by the tendency of metabotropic glutamate receptors to form mGluR heterodimers (Levitz et al., 2016) and to intimately associate with other metabotropic transmitters (Møller et al., 2018, Olivero et al., 2018).

1.5. Future Research

Assessment of the behavioral characteristics and cellular mechanisms underlying of the apparent procognitive effects of NAAG peptidase inhibition will benefit from: 1) testing the efficacy of GCPII inhibition in studies that discriminate between attention and memory consolidation, 2) testing these inhibitors in models of different types of memory, 3) testing GCPII, mGluR2 and mGluR3 null mutant mice in the above studies, 4) application of GCPII, mGluR2 and mGluR3 knock-down methods, GCPII inhibitors and mGluR selective allosteric modulators in discrete brain regions associated with attention, learning and memory, analogous to studies of these drugs in pain pathways (Nonaka et al., 2017), 5) positive results from the prior studies would support assessment within relevant brain regions of the cellular consequences of mGluR activation that mediate procognitive responses.

1.6. Conclusion

A series of object recognition studies have demonstrated the procognitive effect of drugs that inhibit the NAAG inactivating enzyme, glutamate carboxypeptidase II. Extensive biochemical, pharmacologic and gene deletion studies support the conclusion that this effect is mediated by NAAG activation of mGluR3. Considerable opportunities exist to define the broader impact of NAAG and glutamate carboxypeptidase inhibitors on learning, memory consolidation and attention.

Highlight:

The peptide transmitter NAAG has procognitive activity

Acknowledgment:

This research was supported by NIH (R01 MH 79983), Georgetown University Biology Department, and an endowment and generous gifts from Nancy and Daniel Paduano. While the patent for ZJ43 is held by Georgetown University, the authors have no proprietary interest in this compound. Authors have no commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this submitted article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen K,D, Regier M,J, Hsieh C, Tsokas P, Barnard M, Phatarpekar S, Wolk J, Sacktor T,C, Fenton A,A & Hernández A,I (2018) Learning-induced ribosomal RNA is required for memory consolidation in mice-Evidence of differentially expressed rRNA variants in learning and memory. PLoS One, 13(10), e0203374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altinbilek B & Manahan-Vaughan D (2009) A specific role for group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in hippocampal long-term depression and spatial memory. Neuroscience, 158(1), 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes M, & Biala G (2012) The novel object recognition memory: neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cognitive Processing, 13(2), 93–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker G,R, Bashir Z,I, Brown M,W & Warburton E,C (2006) A temporally distinct role for group I and group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in object recognition memory. Learn Mem, 13(2), 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JR, Reilly JL, Harris MS, Patel SR, Kittles R, Badner JA, Prasad KM, Nimgaonkar VL, Keshavan MS & Sweeney JA (2015) Pharmacogenetic associations of the type-3 metabotropic glutamate receptor (GRM3) gene with working memory and clinical symptom response to antipsychotics in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 232(1), 145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdega T, Turi T, Wroblewska B, She D, Chung HS, Kim H & Neale JH (1997) Molecular cloning of a peptidase against N‐acetylaspartylglutamate from a rat hippocampal cDNA library. Journal of Neurochemistry, 69, 2270–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumas S, Ceccom J, Halley H, Francés B & Lassalle J,M (2009) Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 2/3 supports the involvement of the hippocampal mossy fiber pathway on contextual fear memory consolidation. Learn Mem 16(8), 504–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis B, Lyon L, Taylor A, Lane T, Burnet PW, Harrison PJ & Bannerman DM (2015) The role of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in cognition and anxiety: comparative studies in GRM2(−/−), GRM3(−/−) and GRM2/3(−/−) knockout mice. Neuropharmacology, 89, 19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco S, Merega E, Bonfiglio T, Olivero G, Cervetto C, Grilli M, Usai C, Marchi M & Pittaluga A (2016) Presynaptic, release-regulating mGlu2 -preferring and mGlu3 -preferring autoreceptors in CNS: pharmacological profiles and functional roles in demyelinating disease. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173(9), 1465–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Straub RE, Goldberg TE, Yakub I, Callicott JH, Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Bertolino A, Hyde TM, Shannon-Weickert C, Akil M, Crook J, Vakkalanka RK, Balkissoon R, Gibbs RA, Kleinman JE, & Weinberger DR (2004) Variation in GRM3 affects cognition, prefrontal glutamate, and risk for schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A. 101(34), 12604–12609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlström A, Yu Q & Ulfhake B (2011) Behavioral changes in aging female C57BL/6 mice. Neurobiology of Aging, 32(10), 1868–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Xu S, Cui Z, Zhang M, Lin Y, Cai L, Wang Z, Luo X, Zheng Y, Wang Y, Luo Q, Jiang J, Neale JH & Zhong C (2015) Mice lacking glutamate carboxypeptidase II develop normally, but are less susceptible to traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurochemistry, 134(2), 340–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger K,R, Alt. J, Riehm AM & Kaplin AI (2016) Dose-dependent inhibition of GCPII to prevent and treat cognitive impairment in the EAE model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Research, 1635, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczura KJ, Olszewski RT, Bzdega T, Bacich D,J, Heston WD,\ & Neale JH (2013) NAAG peptidase inhibitors and deletion of NAAG peptidase gene enhance memory in novel object recognition test. European Journal of Pharmacology, 701(1–3), 27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin LE, Wang M, Galvin VC, Lightbourne TC, Conn PJ, Arnsten AFT & Paspalas CD (2018) mGluR2 versus mGluR3 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors in Primate Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex: Postsynaptic mGluR3 Strengthen Working Memory Networks. Cerebral Cortex, 28(3), 974–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CA, Brown AM, Auer DP Fone KC (2010) The mGluR2/3 agonist LY379268 reverses postweaning social isolation-induced recognition memory deficits in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 214, 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khacho P, Wang B, Ahlskog N, Hristova E & Bergeron R (2015) Differential effects of N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate on synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are subunit- and pH-dependent in the CA1 region of the mouse hippocampus. Neurobiology of Disease, 82, 580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea. P,M 4th, Wroblewska B, Sarvey J,M & Neale J,H (2001) beta-NAAG rescues LTP from blockade by NAAG in rat dentate gyrus via the type 3 metabotropic glutamate receptor. Journal of Neurophysiology, 85(3), 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitz J, Habrian C, Bharill S, Fu Z, Vafabakhsh R & Isacoff E,Y (2016) Mechanism of Assembly and Cooperativity of Homomeric and Heteromeric Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. Neuron, 92(1), 143–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losi G, Vicini S & Neale J (2004) NAAG fails to antagonize synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in cerebellar granule neurons. Neuropharmacology, 46(4), 490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon L, Burnet P,W, Kew J,N, Corti C, Rawlins J,N,, Lane T, De Filippis B, Harrison P,J & Bannerman D,M (2011) Fractionation of spatial memory in GRM2/3 (mGlu2/mGlu3) double knockout mice reveals a role for group II metabotropic glutamate receptors at the interface between arousal and cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36(13), 2616–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller T,C, Hottin J, Clerté C, Zwier J,M, Durroux T, Rondard P, Prézeau L, Royer C,A, Pin J,P, Margeat E & Kniazeff J (2018) Oligomerization of a G protein-coupled receptor in neurons controlled by its structural dynamics. Science Reports, 8(1), 10414–10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J,H, Klinger P,D & Agranoff B,W (1973) Camptothecin blocks memory of conditioned avoidance in the goldfish. Science, 179,1243–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J,H, Olszewski R,T, Zuo D, Janczura K,J, Profaci C,P, Lavin K,M, Madore J,C & Bzdega T (2011) Advances in understanding the peptide neurotransmitter NAAG and appearance of a new member of the NAAG neuropeptide family. Journal of Neurochemistry, 118(4), 490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J,H, Olszewski R,T, Gehl L,M, Wroblewska B & Bzdega T (2005) The neurotransmitter N-acetylaspartylglutamate in models of pain, ALS, diabetic neuropathy, CNS injury and schizophrenia. Trends in Pharmacological Science, 26(9), 477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T, Yamada T, Ishimura T, Zuo D, Moffett J,R, Neale J,H & Yamamoto T (2017) A role for the locus coeruleus in the analgesic efficacy of N-acetylaspartylglutamate peptidase (GCPII) inhibitors ZJ43 and 2-PMPA. Molecular Pain, 13, 1744806917697008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivero G, Bonfiglio T, Vergassola M, Usai C, Riozzi B, Battaglia G, Nicoletti F & Pittaluga A (2017) Immuno-pharmacological characterization of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors controlling glutamate exocytosis in mouse cortex and spinal cord. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(24), 4785–4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivero G, Grilli M, Vergassola M, Bonfiglio T, Padolecchia C, Garrone B, Di Giorgio F,P, Tongiani S, Usai C, Marchi M & Pittaluga A (2018) 5-HT2A-mGlu2/3 receptor complex in rat spinal cord glutamatergic nerve endings: A 5-HT2A to mGlu2/3 signalling to amplify presynaptic mechanism of auto-control of glutamate exocytosis. Neuropharmacology, 2018, 133, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski R,T, Bukhari N, Zho J,Kozikowski A,P, Wroblewski J,T, Shamimi-Noori S, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T, Vicini S, Barton F,B & Neale J,H (2004) NAAG peptidase inhibition reduces locomotor activity and some stereotypes in the PCP model of schizophrenia via group II mGluR. Journal of Neurochemistry, 89, 876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski R,T, Bzdega T & Neale J,H (2012b) mGluR3 and not mGluR2 receptors mediate the efficacy of NAAG peptidase inhibitor in validated model of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 136(1–3), 160–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski R,T, Janczura K,J, Ball S,R, Madore J,C, Lavin K,M, Lee J,C, Lee M,J, Der E,K, Hark T,J, Farago P,R, Profaci C,P, Bzdega T & Neale J,H (2012a) NAAG peptidase inhibitors block cognitive deficit induced by MK-801 and motor activation induced by d-amphetamine in animal models of schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry, 2, e145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski R,T, Janczura K,J, Bzdega T, Der E,K, Venzor F, O’Rourke B, Hark T,J, Craddock K,E, Balasubramanian S, Moussa C & Neale J,H (2017) NAAG Peptidase Inhibitors Act via mGluR3: Animal Models of Memory, Alzheimer’s, and Ethanol Intoxication. Neurochemical Research, 42(9), 2646–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski R,T, Wegorzewska M,M, Monteiro A,C, Krolikowski K,A, Zhou J, Kozikowski A,P, Long K, Mastropaolo J, Deutsch S,I & Neale J,H (2008) Phencyclidine and dizocilpine induced behaviors reduced by N-acetylaspartylglutamate peptidase inhibition via metabotropic glutamate receptors. Biological Psychiatry, 63(1), 86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsikas N, Kaffe E & Markou A (2012) The metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor antagonist LY341495 differentially affects recognition memory in rats. Behavioral Brain Research, 230(2), 374–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöschel B, Wroblewska B, Heinemann U & Manahan-Vaughan D (2005) The metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR3 is critically required for hippocampal long-term depression and modulates long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats. Cerebral Cortex, 15(9), 1414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A & Levitz J (2018) Glutamatergic Signaling in the Central Nervous System: Ionotropic and Metabotropic Receptors in Concert. Neuron, 98(6),1080–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romei C, Raiteri M & Raiteri L (2013) Glycine release is regulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors sensitive to mGluR2/3 ligands and activated by N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG). Neuropharmacology, 66, 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Tanaka K, Ohnishi Y, Teramoto T, Irifune M & Nishikawa T (2004) Inhibitory effects of group II mGluR-related drugs on memory performance in mice. Physiol Behav, 80(5), 747–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusher B,S, Robinson M,B, Tsai G, Simmons M,L, Richards S,S & Coyle J,T (1990) Rat brain N-acetylated alpha-linked acidic dipeptidase activity. Purification and immunologic characterization. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 265(34), 21297–21301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusher B,S, Vornov J,J, Thomas A,G, Hurn P,D, Harukuni I, Bhardwaj A, Traystman R,J, Robinson M,B, Britton P, Lu X,C, Tortella F,C, Wozniak K,M, Yudkoff M, Potter B,M & Jackson P,F (1999) Selective inhibition of NAALADase, which converts NAAG to glutamate, reduces ischemic brain injury. Nature Medicine, 5(12), 1396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli S, Ballard T, Gatti-McArthur S, Richards G,J, Kapps M, Woltering T, Wichmann J, Stadler H, Feldon J & Pryce C,R (2005) Effects of the mGluR2/3 agonist LY354740 on computerized tasks of attention and working memory in marmoset monkeys. Psychopharmacology, (Berl), 179, 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A,G, Wenthur C,J, Xiang Z, Rook J,M, Emmitte K,A, Niswender C,M, Lindsley C,W & Conn P,J (2015) Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 activation is required for long-term depression in medial prefrontal cortex and fear extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A, 112(4), 1196–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster S,J, Bachstetter A,D & Van Eldik L,J (2013) Comprehensive behavioral characterization of an APP/PS-1 double knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy, 5(3), 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewska B, Santi M,R & Neale J,H (1998) N-acetylaspartylglutamate activates cyclic AMP-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar astrocytes. Glia, 24(2), 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewska B, Wegorzewska I,N, Bzdega T, Olszewski R,T & Neale J,H (2006) Differential negative coupling of type 3 metabotropic glutamate receptor to cyclic GMP levels in neurons and astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry, 96(4), 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Saito O, Aoe T, Bartolozzi A, Sarva J, Zhou J, Kozikowski A, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T & Neale J,H, (2007) Local administration of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) peptidase inhibitors is analgesic in peripheral pain in rats. European Journal of Neuroscience, 25(1), 147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Zhao X, Sarva J, Kozikowski A, Neale J,H & Lyeth B,G (2005) NAAG peptidase inhibitor reduces acute neuronal degeneration and astrocyte damage following lateral fluid percussion TBI in rats. Journal of Neurotrauma, 22(2), 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Zhao X, Van K,C, Bzdega T, Smyth A, Zhou J, Kozikowski A,P, Jiang J, O’Connor W,T, Berman R,F, Neale J,H & Lyeth B,G (2006) NAAG peptidase inhibitor increases dialysate NAAG and reduces glutamate, aspartate and GABA levels in the dorsal hippocampus following fluid percussion injury in the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry, 97(4), 1015–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo D, Bzdega T, Olszewski R,T, Moffett J,R & Neale J,H (2012) Effects of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) peptidase inhibition on release of glutamate and dopamine in prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens in phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287(26), 21773–21782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]