Abstract

Background

As thousands of electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) refill fluids continue to be formulated and distributed, there is a growing need to understand the cytotoxicity of the flavouring chemicals and solvents used in these products to ensure they are safe. The purpose of this study was to compare the cytotoxicity of e-cigarette refill fluids/solvents and their corresponding aerosols using in vitro cultured cells.

Methods

E-cigarette refill fluids and do-it-yourself products were screened in liquid and aerosol form for cytotoxicity using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. The sensitivity of human pulmonary fibroblasts, lung epithelial cells (A549) and human embryonic stem cells to liquids and aerosols was compared. Aerosols were produced using Johnson Creek’s Vea cartomizer style e-cigarette.

Results

A hierarchy of potency was established for the aerosolised products. Our data show that (1) e-cigarette aerosols can produce cytotoxic effects in cultured cells, (2) four patterns of cytotoxicity were found when comparing refill fluids and their corresponding aerosols, (3) fluids accurately predicted aerosol cytotoxicity 74% of the time, (4) stem cells were often more sensitive to aerosols than differentiated cells and (5) 91% of the aerosols made from refill fluids containing only glycerin were cytotoxic, even when produced at a low voltage.

Conclusions

Our data show that various flavours/brands of e-cigarette refill fluids and their aerosols are cytotoxic and demonstrate the need for further evaluation of e-cigarette products to better understand their potential health effects.

INTRODUCTION

The variety of electronic cigarette (e-cigarettes) refill fluids is increasing rapidly,1 and e-cigarettes have become popular with teens as well as adults who previously did not use tobacco products.2 This rapid rise in e-cigarette popularity has occurred with little information on their safety and health risks. A recent risk assessment concluded that additional work is needed to better understand the public health impact that e-cigarettes pose.3

Cig-alike models of e-cigarette come with prefilled cartomizers that contain a solvent, such as propylene glycol or glycerin (also called vegetable glycerin or glycerol), flavourings and nicotine (often ranging from 0 to 36 mg/mL).4,5 Users also purchase bottles of refill fluid that can be manually dripped into e-cigarette cartomizers. Some refill products, referred to as do-it-yourself (DIY), are sold as concentrates that can be diluted by the user. Refill fluids are available in numerous flavours, are commonly customisable in nicotine concentration and solvents, and are often more cost-effective than prefilled cartomizers.

Given their rise in popularity, it is critical to understand the positive and negative health effects that e-cigarettes introduce. Over 25 case reports attribute adverse health effects to e-cigarettes.6 These include systemic effects involving the respiratory, cardiac and digestive systems, unintentional and intentional poisonings, and injuries due to explosion. Several in vitro studies found that e-cigarettes lead to activation of cell stress pathways including inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis and DNA damage.7–12 In addition, many negative and some positive symptoms have been attributed to e-cigarette exposure by users self-reporting on Internet forum websites.13,14 The FDA has documented minor to severe adverse events reported to them by e-cigarette users.15,16 The above adverse effects may be attributed to nicotine withdrawal or overdose,6,13 metal particles and nanoparticles in e-cigarette aerosol,17–19 reactive oxygen species, or flavourings such as diacetyl and cinnamaldehyde.20,21 Several studies found carbonyl compounds, such as acrolein and formaldehyde, in e-cigarette aerosol.22–24 These highly reactive and toxic compounds are produced by the pyrolysis of the solvents (eg, propylene glycol or glycerin).22,25,26

Our laboratory recently showed that the cytotoxicity of 33 e-cigarette refill fluids and three DIY products varied significantly when tested with adult and embryonic cells.27 The cytotoxicity of some products was correlated with the number and concentration of the chemicals used to flavour the refill fluids. Cinnamon-flavoured products were particularly cytotoxic, and cinnamaldehyde was identified as the most potent additive in these fluids.21 We also reported that cinnamaldehyde is widely used in refill fluids, including popular fruity and sweet flavours, and that it produces adverse effects on cells at doses that do not cause cell death.28

The purpose of this study was to follow-up on our prior publication dealing with the cytotoxicity of refill fluids.27 Specifically, we compare the cytotoxicity of these refill fluids and their corresponding aerosols using three different cell types and also evaluated the cytotoxicity of aerosols made from authentic propylene glycol and glycerin, the two most commonly used refill fluid solvents.

METHODS

Sources of e-cigarette products

Thirty-six e-cigarette refill fluids were tested in a previous screen27 with the exception #3 Marcado (Johnson Creek), which was replaced with a duplicate bottle (#73 Marcado, Johnson Creek). The tested products were manufactured by Freedom Smoke USA (Tucson, Arizona, USA), Global Smoke (Los Angeles, California, USA), Johnson Creek (Johnson Creek, Wisconsin) and Red Oak (a subsidiary of Johnson Creek). Thirty five of the original 36 bottles of refill fluids and e-cigarette DIY products containing various flavourings and nicotine concentrations were evaluated (table 1). The products were chosen to give a range of manufacturers, solvents, nicotine concentrations and flavours. All bottles were given an inventory number and stored at 4°C for 1 year before rescreening. Manufacturers labelled their products ‘vegetable glycerin’ and/or ‘glycerol’, which are chemically the same. We refer to both terms as ‘glycerin’ when discussing them in the text, but use the manufacturers’ terms (glycerol and vegetable glycerin) in table 1 to show actual labelling of each product.

Table 1.

E-cigarette product information and human pulmonary fibroblast cytotoxicity data of the fluids and aerosols

| Aerosol (%) |

<70% of CN |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inv. no | Refill fluid (company) | Flavour category | Nicotine (mg/mL) | Solvent | NOAEL | LOAEL | IC50 | RF redo IC50 (%) | A | RF |

| 6 | Valencia (R) | Fruit | 18 | G, V | 1.008 | 3.360 | >3 | >1 | No | No |

| 34 | JC Original (J) | Tobacco | 11 | P, V | 0.031 | 0.092 | >3 | >1 | No | No |

| 8 | Arctic Menthol (J) | Mint/tobacco | 18 | P, V, G | 0.744 | 2.479 | >2 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Chocolate Truffle (J) | Chocolate/creamy/tob. | 18 | P, V, G | 0.721 | 2.403 | >2 | 2.038 | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | JC Original (J) | Tobacco | 18 | P, V, G | 0.277 | 0.830 | >2 | >1 | No | No |

| 15 | Simply Strawberry (J) | Fruit | 18 | P, V, G | 0.250 | 0.750 | >2 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | Summer Peach (J) | Fruit | 18 | P, V, G | 0.768 | 2.559 | >2 | >1 | No | No |

| 23 | Menthol Arctic (F) | Mint/menthol | 0 | U | 0.659 | 2.195 | >2 | 1.439 | No | Yes |

| 32 | Propylene Glycol (F) | - | - | P | 0.236 | 0.707 | >2 | 2.109 | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | French Vanilla (J) | Nutty/creamy/tob. | 18 | P, V, G | 0.507 | 1.689 | >1 | >1 | No | No |

| 14 | Mint Chocolate (J) | Mint/chocolate | 18 | P, V, G | 0.190 | 0.570 | >1 | >1 | No | No |

| 17 | Tennessee Cured (J) | Tobacco | 18 | P, V, G | 0.519 | 1.730 | >1 | >1 | No | No |

| 27 | Caramel (F) | Creamy/buttery | 6 | U | 0.495 | 1.649 | >1 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 40 | Caramel (G.S.) | Creamy/buttery | 18 | U | 0.172 | 0.516 | >1 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Black Cherry (J) | Fruit/tobacco | 18 | P, V, G | 0.643 | 2.142 | 2.036 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Bubblegum (F) | Candy | 24 | U | 0.660 | 2.201 | 1.635 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Espresso (J) | Coffee/creamy/tob. | 18 | P, V, G | 0.727 | 2.423 | 1.587E | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | Caramel (F) | Creamy/buttery | 0 | U | 0.233 | 0.698 | 1.499 | 0.560 | Yes | Yes |

| 31 | Tennessee Cured (J) | Tobacco | 11 | P, V | 0.704 | 2.347 | 1.420 | >1 | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | Pure Nicotine Liquid (F) | - | U* | P | 0.655 | 2.184 | 1.385 | 0.750 | Yes | Yes |

| 3 (73) | Marcado (R) | Spiced/tobacco | 18 | G, V | 0.850 | 2.834 | 1.382 | 0.210 | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Island (R) | Fruit | 18 | G, V | 0.268 | 0.805 | 1.174 | 1.456 | Yes | Yes |

| 41 | Butterscotch (F) | Creamy/buttery | 0 | U | 0.213 | 0.639 | 1.020 | 0.700 | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Tennessee Cured (R) | Tobacco | 18 | G, V | 0.525 | 1.749 | 0.875 | 1.101 | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | Vanilla Tahity (F) | Creamy/buttery | 0 | U | 0.160 | 0.479 | 0.563 | 0.640 | Yes | Yes |

| 33 | Vegetable Glycerin (F) | - | - | V | 0.152 | 0.457 | 0.517 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 1 | Domestic (R) | Tobacco | 18 | G, V | 0.148 | 0.443 | 0.453 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 7 | Wisconsin Frost (R) | Mint/tobacco | 18 | G, V | 0.170 | 0.511 | 0.426 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 22 | Cinnamon Ceylon (F) | Spiced/cinnamon | 0 | U | 0.092 | 0.306 | 0.408 | 0.020 | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | Butterfinger (F) | Creamy/buttery | 24 | U | 0.043 | 0.143 | 0.333 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 28 | Caramel (F) | Creamy/buttery | 6 | V | 0.044 | 0.146 | 0.119 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 30 | Butterscotch (F) | Creamy/buttery | 0 | V | 0.044 | 0.146 | 0.105 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 29 | Butterscotch (F) | Creamy/buttery | 6 | V | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.023 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 26 | Caramel (F) | Creamy/buttery | 0 | V | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.021 | >1 | Yes | No |

| 4 | Swiss Dark (R) | Chocolate/creamy/tob. | 18 | G, V | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.303 | Yes | Yes |

The column titled <70% of CN denotes a response in the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay that fell below 70% of the control. Solvent (P, G or V) was recorded as it appears on the company’s label.

Products are ordered based on the aerosol inhibitory concentration at 50% (IC50) values.

A, aerosol; CN, control; F, Freedom Smoke USA; G, glycerol; G.S. Global Smoke; Inv. no, inventory number; J, Johnson Creek; LOAEL, lowest observed adverse effect levels; NOAELP, no observed adverse effect levels; P, propylene glycol; R, Red Oak; RF, refill fluid;tob, tobacco; U, unknown solvent type; U*, unknown nicotine concentration; V, vegetable glycerin.

E-cigarette aerosol collection

E-cigarette aerosol was produced using a smoking machine described previously.28 The puffer box was connected with Cole Parmer MasterFlex Tygon tubing (Vernon Hills, Illinois, USA) to a MasterFlex peristaltic pump (Barnart Company, Barrington, Illinois, USA; Model #7520–00). The line between the smoking machine and the pump contained a T connector (Fisher Scientific) that held the e-cigarette. The peristaltic pump was warmed up for a minimum of 15 min before collecting aerosol into culture medium in a round bottom flask submerged into an ice bath.

Each batch of aerosol was prepared with a fresh unused cartomizer. Empty cartomizers were purchased from Johnson Creek for use with their 2.85 V Vea model e-cigarette. To avoid dry puffing, 1 mL of refill fluid was pipetted into each cartomizer as recommended by the vendor, and weights were taken before and after puffing to monitor fluid consumption. The peristaltic pump speed was reduced to zero until just before every puff at which time pump speed was increased to the desired level. The smoking machine was calibrated to draw a puff volume of 30 mL for a duration of 4.3 s, which is the average puff duration for e-cigarette users29 at a frequency of 10 puffs/hour. For each batch of aerosol, 24 puffs were collected into 4 mL of culture medium.

Cell culture

The human pulmonary fibroblasts (hPFs) were chosen as they were used in our previous studies, they are one of the first cell types exposed to inhaled aerosol and they are involved in development of lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.30–32 hPFs (ScienCell, Carlsbad, California, USA) were cultured using the manufacturer’s protocol in complete fibroblast medium containing 2% fetal bovine serum, 1% fibroblast growth serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. hPFs were dispersed into single cells and plated at 4000 cells/well in a 96-well plate using a BioMate 3S Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Chino, California, USA) based standard curve.

A549 lung epithelial cells (ATCC CCL-185 cells, Manassas, Virginia, USA) are often used in toxicological and inhalation testing. A549 cells were cultured using the distributor’s protocol in ATCC F-12K medium and 10% fetal bovine serum using tissue culture flasks. A549 cells were plated as single cells at a density of 50 000 cells/well in 96-well plates using a BioMate 3S Spectrophotometer-based standard curve.

The pluripotent human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) were used as a model for early postimplantation human embryos.33 The hESCs (H9) (WiCell, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) were cultured on Matrigel in mTeSR medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) in six-well plates as described in detail previously.34 For experiments, colonies of 2–10 cells were plated using a standard curve-based method where 40 000 cells/well in a 96-well plate were measured.

Each cell type was plated at a density that grew to about 80% confluency by the end of the experiment.

MTT assay

E-cigarette fluids and their aerosols were tested in 96-well plates in dose–response experiments using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay to observe cytotoxic effects on hPF, hESC and A549 cells. Dilutions of aerosols were tested at concentrations ranging from 0.0006 to 6 TPE (TPE = total puff equivalents, which is the number of puffs/mL of culture medium). To compare non-aerosolised and aerosolised refill fluid, TPE were converted to percentage (%) using the density of the fluid and the weight/puff of the aerosol. Density was determined by comparing the weight of the fluid with that of water on an analytical balance. Then, the weight of one puff of e-cigarette aerosol was calculated by subtracting the weight of the cartomizer before use and after dividing the weight by 24 (number of puffs taken). The weight of one puff was divided by the density of the fluid and converted to a percentage using the total number of puffs/mL of medium.

Thirty-six refill fluids and DIY e-cigarette products were screened for toxicity in a previous study.27 To determine if these products showed similar toxicity after storage at 4°C, dilutions of the 35 refill fluids and DIY products were rescreened without aerosolisation using the MTT assay at concentrations of 0.001%, 0.01%, 0.03%, 0.1%, 0.3% and 1.0%. To make dilutions, all fluids were brought to room temperature, and mixed thoroughly by pipetting.

The MTT assay was performed as described in detail previously.35,36 Refill fluids and aerosols diluted with culture medium were tested in 96-well plates with negative controls located to the left and to the right of the concentrations tested. The control adjacent to the highest concentrations checked for vapour effects produced by volatile fluids and aerosols.35,37 When a vapour effect was found, a lower high concentration was used to rescreen. Cells and treatments were plated together and incubated for 48 hours, and then examined microscopically to observe the condition of the cells. The MTT solution was added for 2 hours, and the MTT assay was performed. Aerosols were tested in three independent experiments, and means and SE of the mean were used to produce dose–response curves for each cell type. Refill fluids were rescreened a single time to observe their correspondence with the original screen.27 In some cases, an additional high concentration (>1%) of refill fluid was tested to allow comparison of the refill fluid with the highest concentration of aerosol. These additional high concentrations are represented as blue block arrows in figures 1 and 2 and supplementary file S2.

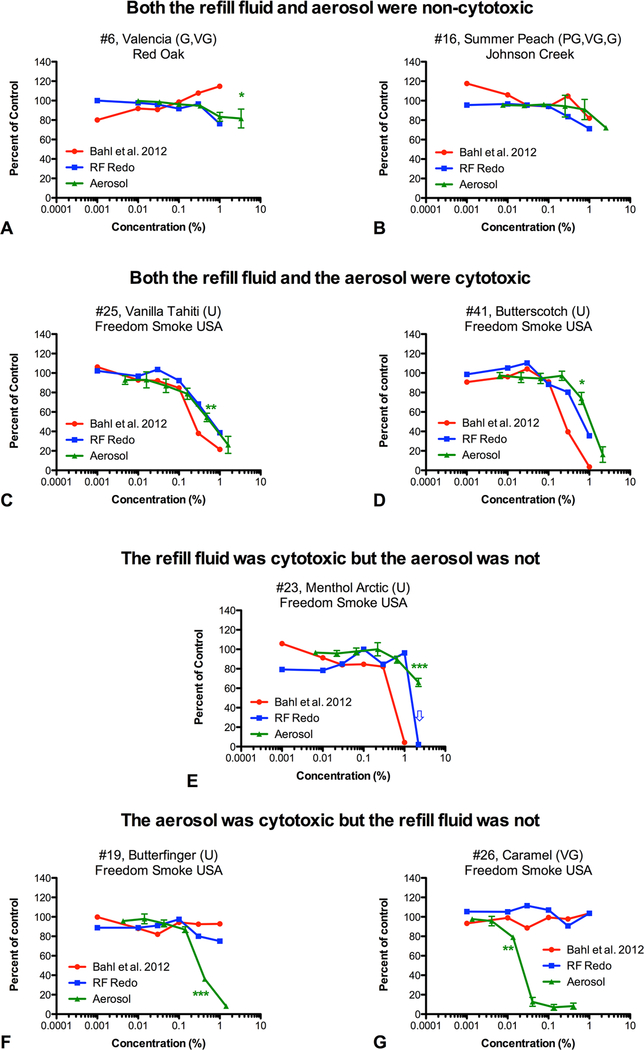

Figure 1.

Four patterns of cytotoxicity for e-cigarette refill fluids (RF) and aerosols. (A and B) Both the RF and aerosol were non-cytotoxic. (C and d) Both the RF and the aerosol were cytotoxic. (e) The RF was cytotoxic but the aerosol was not. (F and G) The aerosol was cytotoxic but the RF was not. Red lines are RF previously screened with human pulmonary fibroblast (hPF).27 Blue lines are the same RF rescreened in this study to determine if storage effected cytotoxicity. Green lines are aerosols produced from each RF and used to treat hPF. For green lines, data are the means and SE of the mean of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate the lowest concentrations that are significantly different from the untreated controls (lowest observed adverse effect level). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

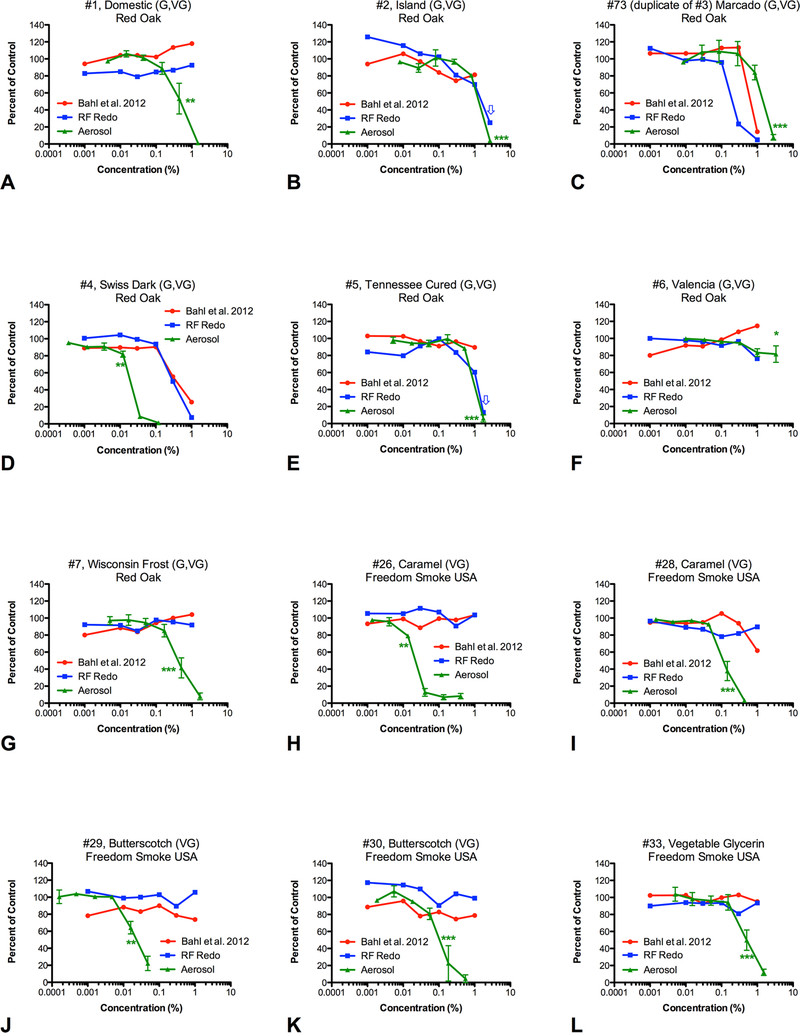

Figure 2.

Most e-cigarette products containing glycerin produce cytotoxic aerosols. (A–L) Comparison of the 11 refill fluids (RF) and one do-ityourself purchased sample of vegetable glycerin. Red lines are RF previously screened with human pulmonary fibroblast (hPF).27 Blue lines are the same RF rescreened in this study to determine if storage effected cytotoxicity. Green lines are aerosols produced from each RF and used to treat hPF. For green lines, data are the means and SE of the mean of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate the lowest concentrations that are significantly different and represent the lowest observed adverse effect level. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Data analysis

For aerosol dose–response experiments, inhibitory concentration at 50% (IC50) values were computed with Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, California, USA) using the log inhibitor versus normalised response-variable slope with the top and bottom constraints set to 100% and 0%, respectively. For the refill fluid redo screen, IC50 values were determined by eye from the dose–response curve. Statistical significance for aerosols was determined using an analysis of variance on three independent experiments using Graph Pad Prism. When significance was found, treated groups were compared with the lowest concentration using Dunnett’s post hoc test, and means were considered significantly different for p<0.05. The no observed adverse effect levels (NOAEL) and the lowest observed adverse effect levels (LOAEL) were determined by statistical significance.

RESULTS

Cytotoxicity of refill fluid and aerosol samples with hPF

Table 1 summarises data on the products used, our inventory numbers, the company of origin, the amount of nicotine/product, the solvent when known, the flavour category, the dose–response data (NOAEL, LOAEL and IC50) and the cytotoxicity data (response <70% of the control) for both the fluids and their corresponding aerosols. All of the products were considered refill fluids except for #24, #32 and #33, which were DIY products. These products ranged in potency (table 1), and all dose–response curves for the 35 aerosols, with one exception, yielded concentrations that were significantly more toxic than the lowest concentration tested. While flavouring categories, such as creamy/buttery, mint/menthol, tobacco and fruit were within the hierarchy of potency, 6 of the 14 ‘creamy’ aerosols (#4, #19, #26, #28, #29, #30) were the most potent in this screen.

Generally, unheated refill fluids produced similar dose–response data to that obtained in our original screen (supplementary files S1–3), showing that cytotoxicity of the refill fluids did not change measurably when stored for prolonged times at 4°C. Clear exceptions to this are #34 JC Original by Johnson Creek (supplementary file S1G) and #40 Caramel by Global Smoke (supplementary file S2R), which lost potency with storage. Differences between the previous screen and current rescreen may be due to ageing of the product or escape of volatile flavouring chemicals during storage.

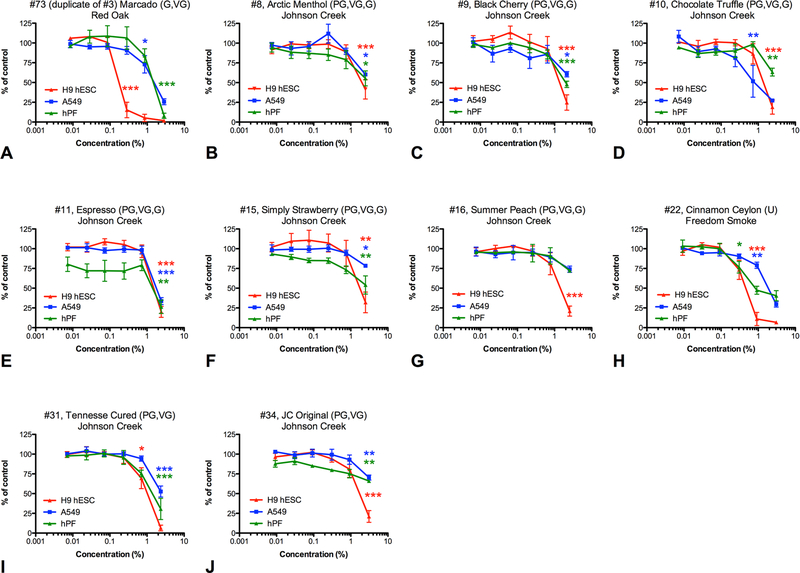

Sensitivity of adult respiratory cells and stem cells

A subset of aerosols from the refill fluids that were most cytotoxic in the original screen was further tested using hESC and A549 human lung epithelial cells (figure 3). hESCs were more sensitive than hPF and A549 cells to about 50% and 40% of the aerosols, respectively. This agrees with our previous data showing that stem cells are more sensitive than differentiated adult cells to e-cigarette products.27 The two adult lung cell types responded similarly to 80% of the aerosol treatments.

Figure 3.

Two adult respiratory cell types and a pluripotent cell compared for sensitivity to e-cigarette aerosols. H9 hESC (red lines), A549 cells (blue lines) and hPF (green lines) were treated with 10 e-cigarette aerosols (A–J). Data are plotted as the means and SE of the mean of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate the lowest concentrations that are significantly different from the untreated control (lowest observed adverse effect level). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. hESC, human embryonic stem cell; hPF, human pulmonary fibroblast.

Patterns of cytotoxicity

The dose–response data from the above screen can be broken down into four patterns of cytotoxicity by determining whether the highest concentration was less or greater than 70% of the control (figure 2; supplementary files 1–3).38 For example, if the sample’s high concentration was <70% of the control, the refill fluid or aerosol was considered cytotoxic. The patterns were characterised as follows: (1) both the refill fluid and its aerosol were non-cytotoxic (7 of 35=20%) (figure 1A,B and supplementary file 1); (2) both the refill fluid and its aerosol were cytotoxic (19 of 35=54%) (figure 1C, D and supplementary file 2); (3) the refill fluid was cytotoxic but the aerosol was not (1 of 35=3%) (figure 1E); and (4) the aerosol was cytotoxic but the refill fluid was not (8 of 35=23%) (figure 1F, G and supplementary file 3). Collectively, when combining patterns (1) and (2), 74% of the 35 unheated refill fluids/DIY products correctly predicted the cytotoxicity of their corresponding aerosol. In some cases, either the refill fluid or aerosol was just above 70% of the control, while the other fell just below 70%. For these graphs, the per cent difference was calculated and if the two numbers were within 10%, they were considered both non-cytotoxic.

Most refill fluids/dIY products containing only glycerin produced cytotoxic aerosols

Ten of the 11 aerosolised glycerin-based refill fluids (91%) were cytotoxic (figure 2A-K). Aerosolised vegetable glycerin by itself, which was purchased from Freedom Smoke USA as a DIY product, was cytotoxic (figure 2L). Only one refill fluid that contained glycerin, #6 Valencia, produced an aerosol that was not cytotoxic (figure 2F).

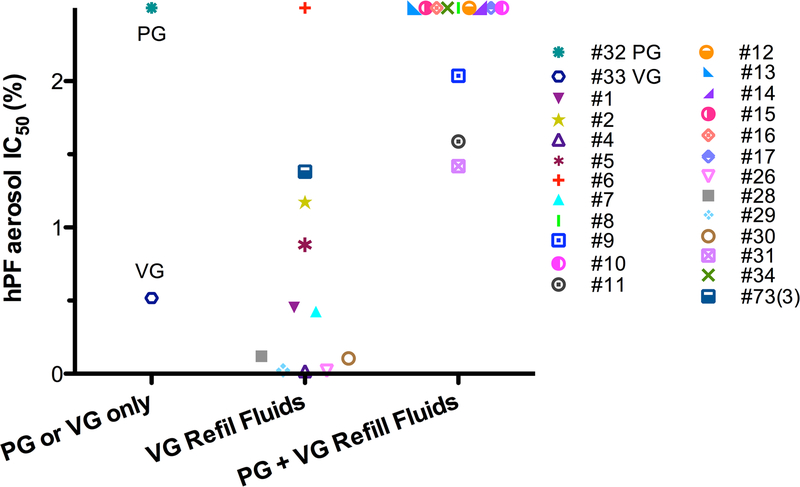

Solvent cytotoxicity

In figure 4, solvent aerosols and aerosols from refill fluids with known solvent compositions read off the label were plotted based on IC50 values and solvent composition. Generally, refill fluid aerosols containing glycerin were the most cytotoxic. In contrast, aerosols containing a mixture of propylene glycol and glycerin were overall less cytotoxic (figure 4). This pattern was also seen for the authentic aerosolised solvents, where propylene glycol showed lower cytotoxicity than glycerin. mixture of propylene glycol and glycerin were overall less cytotoxic (figure 4). This pattern was also seen for the authentic aerosolised solvents, where propylene glycol showed lower cytotoxicity than glycerin.

Figure 4.

Relationship between solvent and aerosol cytotoxicity. The IC50s (concentration in per cent) of the aerosols for the hPF are plotted for each product denoted by inventory number. Lower IC50 values indicate higher cytotoxicity. Points plotted at 2.5 were not potent in the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay, as an IC50 value could not be generated. The ‘PG or VG only’ column denotes aerosols made from PG and VG purchased from Freedom Smoke USA. The ‘VG refill fluids’ column denotes aerosols made from refill fluids containing glycerin, and the ‘PG + VG refill fluids’ column denotes refill fluids that contain propylene glycol and glycerin. Each refill fluid was categorised based on the manufacturer’s labelling. hPF, human pulmonary fibroblast; IC50, inhibitory concentration at 50%.

DISCUSSION

This study compared the cytotoxicity of refill fluids and their corresponding aerosols, established a hierarchy of potency for the e-cigarette aerosols, compared the sensitivity of three different cell types to e-cigarette aerosols and demonstrated that aerosols made from cartomizers with glycerin were more cytotoxic than those made from propylene glycol.

Approximately 74% of the aerosols and their corresponding refill fluids had similar cytotoxicity classification. This correlation suggests that using refill fluids for screening purposes may be useful, practical and economical since there are thousands of unique refill fluids available, which may preclude testing large numbers of aerosols.1 Developing a screening method in which refill fluids are first tested for toxicity followed by testing aerosols from those fluids that show toxicity would be less expensive, faster and less labour intense than producing aerosols for every sample. However, some toxic aerosols may be missed with this strategy and when testing for chemical modifications or generation of new chemicals due to heating, screening of the aerosols would be necessary. In cases where the refill fluid contains only glycerin, predicting aerosol toxicity from refill fluid data would be over 90% accurate based on our data.

Other studies on the cytotoxicity of e-cigarette aerosols have found variable results. In concordance with our study, several groups have reported e-cigarette toxicity and activation of cellular stress pathways, including oxidative stress and inflammation.8,9,11,12,39–42 Similar to our results, one group found that aerosol toxicity varied when using different refill fluids with the same e-cigarette device and therefore concluded that the fluid composition is an important source of toxicity.43 In contrast to our study, some groups have concluded that e-cigarette refill fluids and aerosols are not cytotoxic or have relatively low cytotoxicities.44–47 These differences in cytotoxicity that have been reported by different laboratories could be due to variables such as cell type, species, the brand of e-cigarette studied, the voltage/ wattage and the method of aerosol collection. Other groups have used air–liquid interface systems to directly expose human lung cells to e-cigarette aerosols. These studies have shown that a variety of toxicological effects arise including oxidation, stimulated inflammatory response, decreased cell viability, decreased metabolic activity and alterations in gene expression when using a 3D system.7,39,48–50 As a follow-up to our current screen, we are testing a subset of our refill fluids using an air–liquid interface system with intermittent exposure to determine if toxicity is similar in 3D culture.

Several studies have identified flavouring chemicals in e-cigarettes that may be potentially harmful including cinnamaldehyde (cinnamon), benzaldehyde (cherry) and 2,5-dimethypyrazine (chocolate).28,51,52 The hierarchy of potency generated for the aerosol dose–response data in our study shows that a variety of flavoured refill fluids are cytotoxic. Of the six most cytotoxic aerosols, five were in the creamy/buttery flavour category exclusively (ie, #19 Butterfinger, #28 Caramel, #30 Butterscotch, #29 Butterscotch and #26 Caramel), while the sixth was a mix of tobacco, chocolate and creamy/buttery (ie, #4 Swiss Dark). These six products are glycerin based and have IC50 values lower than that of the vegetable glycerin DIY product (#33). Due to this, it is plausible that their increased potency is related to the flavouring chemicals. Diacetyl and 2,3-pentanedione, which have been linked to lung disease in humans and rats,53–55 are frequently found in creamy/buttery refill fluids,20,56 and could be contributing to the cytotoxicity observed in our study.

All aerosols tested in this study, including those with relatively low potency, were significantly different from untreated controls except for #16 Summer Peach (figure 2B), and the majority of the refill fluids produced aerosol that reduced cell survival to 70% of the control or lower. While our in vitro studies cannot be applied directly to humans, some human data have shown that chronic exposure to e-cigarette aerosol may be linked to adverse health effects.6,13,14 However, it is probable that not all users are equally affected by e-cigarette products, as several studies have reported beneficial effects or no major adverse effects.6,13,14,57–59 hESCs, which model a postimplantation stage in human development,33 were often more sensitive to e-cigarette aerosols than differentiated adult cells. This trend is in line with the our original fluid screen, in which the two stem cell types were more sensitive than adult lung cells.27 Studies that have addressed e-cigarette use during pregnancy in animals have found alterations in cardiac development (zebrafish), behavioural changes (male mice) and impairment of developmental rate and brood size (Caenorhabditis elegans).42,60,61 Additionally, one case report describes a 1-day old infant with colonic necrotising enterocolitits, where the mother’s e-cigarette use throughout pregnancy and during labour was speculated to be the cause.62 The above studies indicate a need for additional research on the health effects of prenatal exposure to e-cigarette aerosol, especially since pregnant women sometimes switch from tobacco cigarettes to e-cigarettes to reduce harm to their embryo/fetus.63,64

One of the most important findings in this study was that aerosolised glycerin was more cytotoxic than aerosolised propylene glycol under normal conditions of use and without dry puffing. Our results are supported by other e-cigarette studies that used different cell types and showed that the solvents themselves caused toxicological effects in vitro.49,50 While the reported concentrations of carbonyl compounds in e-cigarette aerosols have varied,22,24,65–67 recent studies indicate that aerosolisation of glycerin produces carbonyls that could account for the cytoxicity we observed.22,67 The cytotoxicity of the solvents is of particular importance given the growing popularity of glycerin-based refill fluids which produce a thicker aerosol cloud.14 Additionally, some refill fluids are advertised as propylene glycol free, likely to provide a product to users with propylene glycol allergies and on many websites users are able to customise their propylene glycol/ glycerin concentrations.14,68

In conclusion, this study shows that (1) aerosolised e-cigarette products vary in their cytotoxicity with creamy/buttery flavours being the most potent; (2) hESCs were often more sensitive than the adult lung cells to e-cigarette aerosols; (3) four patterns of cytotoxicity emerged when screening refill fluids and their corresponding aerosols; (4) about 74% of the time, cytotoxicity data from the refill fluids and aerosols correlated well; (5) using refill fluids to screen followed by focused screening of aerosols is a fast, inexpensive and less laborious method for identifying products that may produce cytotoxicity; (6) 91% of the time, glycerin-based refill fluids produced aerosols that were cytotoxic using a 2.85 V cartomizer style e-cigarette; and (7) when compared with propylene glycol and mixed solvent products, aerosols from glycerin-based products produced greater cytotoxicity. These data demonstrate that e-cigarette fluids and aerosols are often cytotoxic to human cells and may be hazardous to the respiratory system. This study provides new information to help guide the regulation of these products and to help users of e-cigarettes avoid products that may be harmful to their health.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds?

Thousands of refill fluids with unique flavourings are available online and in shops around the world making screening in aerosol form difficult.

Cytotoxicity in general did not change when refill fluids were stored at 4°C for 1 year.

Stem cells were generally more sensitive than lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells to aerosols.

Seventy-four per cent of the time refill fluid cytotoxicity data accurately predicted the toxicity of the corresponding aerosol, signifying that toxicity screens could be done with fluids.

Aerosols from the creamy/buttery flavoured refill fluids were more cytotoxic than any other flavour group.

Glycerin-based refill fluids produced aerosols that were cytotoxic 91% of the time indicating that glycerin alone may be more harmful than propylene glycol or mixed solvent products.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Victor Camberos, Michael Dang, Jisoo Kim, Alex Razo and Eriel Datuin for their help making aerosol preparations, and My Hua for her helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent The project did not involve humans.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

data sharing statement All of the relevant data are included in the manuscript.

RefeRences

- 1.Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii3–iii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. Electronic Cigarette Use among adults: united States, 2014. 2015:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meng Q, Schwander S, Son Y, et al. Has the mist been peered through? Revisiting the building blocks of human health risk assessment for electronic cigarette use. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2016;22:558–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis B, Dang M, Kim J, et al. Nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarette refill and do-it-yourself fluids. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trtchounian A, Williams M, Talbot P. Conventional and electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have different smoking characteristics. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:905–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hua M, Talbot P. Potential health effects of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review of case reports. Prev Med Rep 2016;4:169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leigh NJ, Lawton RI, Hershberger PA, et al. Flavourings significantly affect inhalation toxicity of aerosol generated from electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Tob Control 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii81–ii87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shivalingappa PC, Hole R, Westphal CV, et al. Airway exposure to E-Cigarette Vapors impairs autophagy and induces Aggresome formation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2015:6367–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji EH, Sun B, Zhao T, et al. Characterization of Electronic Cigarette Aerosol and its induction of Oxidative stress response in Oral keratinocytes. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu V, Rahimy M, Korrapati A, et al. Electronic cigarettes induce DNA strand breaks and cell death independently of nicotine in cell lines. Oral Oncol 2016;52:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweitzer KS, Chen SX, Law S, et al. Endothelial disruptive proinflammatory effects of nicotine and e-cigarette vapor exposures. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015;309:L175–L187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sancilio S, Gallorini M, Cataldi A, et al. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction by e-cigarette fluids in human gingival fibroblasts. Clin Oral Investig 2016;20:477–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua M, Alfi M, Talbot P. Health-related effects reported by electronic cigarette users in online forums. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e59–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Q, Zhan Y, Wang L, et al. Analysis of symptoms and their potential associations with e-liquids’ components: a social media study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen IL. FDA summary of adverse events on electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:615–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durmowicz EL, Rudy SF, Chen IL. Electronic cigarettes: analysis of FDA adverse experience reports in non-users. Tob Control 2016;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams M, Villarreal A, Bozhilov K, et al. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PLoS One 2013;8:e57987–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerner CA, Sundar IK, Watson RM, et al. Environmental health hazards of e-cigarettes and their components: oxidants and copper in e-cigarette aerosols. Environ Pollut 2015;198:100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schober W, Szendrei K, Matzen W, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) impairs indoor air quality and increases FeNO levels of e-cigarette consumers. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2014;217:628–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farsalinos KE, Kistler KA, Gillman G, et al. Evaluation of electronic cigarette liquids and aerosol for the presence of selected inhalation toxins. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:168–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behar RZ, Davis B, Wang Y, et al. Identification of toxicants in cinnamon-flavored electronic cigarette refill fluids. Toxicology in Vitro 2014;28:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sleiman M, Logue JM, Montesinos VN, et al. Emissions from electronic cigarettes: key parameters affecting the Release of Harmful Chemicals. Environ Sci Technol 2016;50:9644–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen RP, Luo W, Pankow JF, et al. Hidden formaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosols. N Engl J Med 2015;372:392–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Fik M, et al. Carbonyl compounds in Electronic Cigarette Vapors: effects of Nicotine Solvent and Battery output voltage. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2014;16:1319–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laino T, Tuma C, Curioni A, et al. A revisited picture of the mechanism of glycerol dehydration. J Phys Chem A 2011;115:3592–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laino T, Tuma C, Moor P, et al. Mechanisms of propylene glycol and triacetin pyrolysis. J Phys Chem A 2012;116:4602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bahl V, Lin S, Xu N, et al. Comparison of electronic cigarette refill fluid cytotoxicity using embryonic and adult models. Reprod Toxicol 2012;34:529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behar RZ, Luo W, Lin SC, et al. Distribution, quantification and toxicity of cinnamaldehyde in electronic cigarette refill fluids and aerosols. Tob Control 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii94–ii102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hua M, Yip H, Talbot P. Mining data on usage of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) from YouTube videos. Tob Control 2013;22:103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallgren O, Nihlberg K, Dahlbäck M, et al. Altered fibroblast proteoglycan production in COPD. Respir Res 2010;11:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitamura H, Cambier S, Somanath S, et al. Mouse and human lung fibroblasts regulate dendritic cell trafficking, airway inflammation, and fibrosis through integrin αvβ8-mediated activation of TGF-β. J Clin Invest 2011;121:2863–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Togo S, Holz O, Liu X, et al. Lung fibroblast repair functions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are altered by multiple mechanisms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:248–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nichols J, Smith A. The origin and identity of embryonic stem cells. Development 2011;138:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin S, Talbot P. Methods for culturing mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol 2011;690:31–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behar RZ, Bahl V, Wang Y, et al. A method for rapid dose-response screening of environmental chemicals using human embryonic stem cells. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2012;66:238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behar RZ, Bahl V, Wang Y, et al. Adaptation of stem cells to 96-well plate assays: use of human embryonic and mouse neural stem cells in the MTT assay. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol 2012;Chapter 1:Unit 1C.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behar RZ, Davis B, Wang Y, et al. Identification of toxicants in cinnamon-flavored electronic cigarette refill fluids. Toxicol In Vitro 2014;28:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.I.S. EN ISO 10993–5. Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 5: tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. 2009:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerner CA, Sundar IK, Yao H, et al. Vapors produced by electronic cigarettes and e-juices with flavorings induce toxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response in lung epithelial cells and in mouse lung. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higham A, Rattray NJ, Dewhurst JA, et al. Electronic cigarette exposure triggers neutrophil inflammatory responses. Respir Res 2016;17:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Q, Jiang D, Minor M, et al. Electronic cigarette liquid increases inflammation and virus infection in primary human airway epithelial cells. PLoS One 2014;9:e108342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panitz D, Swamy H, Nehrke K. A C. elegans model of electronic cigarette use: physiological effects of e-liquids in Nematodes. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2015;16:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Putzhammer R, Doppler C, Jakschitz T, et al. Vapours of US and EU Market Leader Electronic Cigarette Brands and Liquids are cytotoxic for human vascular endothelial cells. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157337–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misra M, Leverette R, Cooper B, et al. Comparative in Vitro Toxicity Profile of Electronic and tobacco cigarettes, smokeless tobacco and nicotine replacement therapy Products: e-liquids, extracts and Collected Aerosols. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:11325–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romagna G, Allifranchini E, Bocchietto E, et al. Cytotoxicity evaluation of electronic cigarette vapor extract on cultured mammalian fibroblasts (ClearStream-LIFE): comparison with tobacco cigarette smoke extract. Inhal Toxicol 2013;25:354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teasdale JE, Newby AC, Timpson NJ, et al. Cigarette smoke but not electronic cigarette aerosol activates a stress response in human coronary artery endothelial cells in culture. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;163:256–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor M, Carr T, Oke O, et al. E-cigarette aerosols induce lower oxidative stress in vitro when compared to tobacco smoke. Toxicol Mech Methods 2016;26:465–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moses E, Wang T, Corbett S, et al. Molecular impact of electronic cigarette aerosol exposure in human bronchial epithelium. Toxicol Sci 2016:kfw198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheffler S, Dieken H, Krischenowski O, et al. Evaluation of E-cigarette liquid vapor and mainstream cigarette smoke after direct exposure of primary human bronchial epithelial cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:3915–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cervellati F, Muresan XM, Sticozzi C, et al. Comparative effects between electronic and cigarette smoke in human keratinocytes and epithelial lung cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2014;28:999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Prokopowicz A, et al. Cherry-flavoured electronic cigarettes expose users to the inhalation irritant, benzaldehyde. Thorax 2016;71:376–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherwood CL, Boitano S. Airway epithelial cell exposure to distinct e-cigarette liquid flavorings reveals toxicity thresholds and activation of CFTR by the chocolate flavoring 2,5-dimethypyrazine. Respir Res 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harber P, Saechao K, Boomus C. Diacetyl-Induced lung disease. Toxicol Rev 2006;25:261–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanwal R, Kullman G, Piacitelli C, et al. Evaluation of flavorings-related lung disease risk at six microwave popcorn plants. J Occup Environ Med 2006;48:149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hubbs AF, Cumpston AM, Goldsmith WT, et al. Respiratory and olfactory cytotoxicity of inhaled 2,3-pentanedione in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Pathol 2012;181:829–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allen JG, Flanigan SS, LeBlanc M, et al. Response to “Comment on ‘Flavoring Chemicals in E-Cigarettes: Diacetyl, 2,3-Pentanedione, and Acetoin in a Sample of 51 Products, Including Fruit-, Candy-, and Cocktail-Flavored E-Cigarettes’”. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pisinger C, Døssing M. A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Prev Med 2014;69:248–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polosa R, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, et al. Success rates with nicotine personal vaporizers: a prospective 6-month pilot study of smokers not intending to quit. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polosa R, Morjaria J, Caponnetto P, et al. Effect of smoking abstinence and reduction in asthmatic smokers switching to electronic cigarettes: evidence for harm reversal. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:4965–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palpant NJ, Hofsteen P, Pabon L, et al. Cardiac development in zebrafish and human embryonic stem cells is inhibited by exposure to tobacco cigarettes and e-cigarettes. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith D, Aherrera A, Lopez A, et al. Adult behavior in Male mice exposed to E-Cigarette Nicotine Vapors during late prenatal and early Postnatal Life. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137953–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gillen S, Saltzman D. Antenatal exposure to e-cigarette vapor as a possible etiology to total colonic necrotizing enterocolitits: a case report. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2014;2:536–7. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mark KS, Farquhar B, Chisolm MS, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of electronic cigarette use among pregnant women. J Addict Med 2015;9:266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baeza-Loya S, Viswanath H, Carter A, et al. Perceptions about e-cigarette safety may lead to e-smoking during pregnancy. Bull Menninger Clin 2014;78:243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bekki K, Uchiyama S, Ohta K, et al. Carbonyl compounds generated from electronic cigarettes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:11192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uchiyama S, Senoo Y, Hayashida H, et al. Determination of Chemical compounds generated from Second-generation E-cigarettes using a Sorbent Cartridge followed by a Two-step Elution Method. Anal Sci 2016;32:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang P, Chen W, Liao J, et al. A Device-Independent evaluation of Carbonyl Emissions from Heated Electronic Cigarette Solvents. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use among Youth and Young adults. A Report of the Surgeon General 2016:1–298. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.