Abstract

Background

Approximately 8.3–15.9% of patients with clinical stage I non‐small cell lung cancer are subsequently shown to have lymph node metastasis. However, the clinical characteristics of patients with lymph node metastasis in China are not fully understood.

Methods

This is a multicenter retrospective analysis of pathological T1 non‐small cell lung cancer patients who underwent surgical resection from 2 January 2014 to 27 December 2017. Clinical and pathological information was collected with the assistance of the Large‐scale Data Analysis Center of Cancer Precision Medicine‐LinkDoc database. The clinical and pathological factors associated with lymph node metastasis were analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression.

Results

A total of 10 885 participants (51.6% women; 15.3% squamous cell carcinoma) were included in the analysis. The median age was 60.0 years (range 12.9–86.6 years). A total of 1159 patients (10.6%) had metastases in mediastinal nodes (N2), and 640 patients (5.9%) had metastasis in pulmonary lymph nodes (N1). Most patients had T1b lung cancer (4766, 43.8%). Of the patients, 3260 (29.9%) were current or former smokers. The univariate and multivariate analyses showed that younger age, squamous cell carcinoma, poor differentiation, larger tumor size, carcinoembryonic antigen level ≥5 ng/mL, and vascular invasion (+) were significantly associated with higher percentages of lymph node metastases (P < 0.001 for all).

Conclusion

This real‐world study showed the significant association of lymph node metastasis with age, tumor size, histology and differentiation, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and status of vascular invasion. Female patients with T1a adenocarcinoma in the right upper lobe barely had lymph node metastasis.

Keywords: Chinese patients, lymph node metastases, real‐world, risk factors, T1 non‐small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer, particularly non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and is the leading cause of cancer‐related death all over the world, especially in China.1, 2 Increased adoption of radiographic screening methods, such as low‐dose helical computed tomography (CT), high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and positron‐emission tomography/computed tomography (PET‐CT), have resulted in the increased number of early‐stage lung cancers diagnosed.3 The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer has defined T1 NSCLC by tumor size ≤3 cm in the greatest dimension surrounded by lung or visceral pleura without bronchoscopic evidence of invasion more proximal than the lobar bronchus.4 The percentage of nodal or extrathoracic metastases has been reported to be >20% in T1 NSCLC patients.5, 6, 7 Surgery is still the standard treatment for T1 NSCLC, of which lobectomy with the dissection of hilar (N1) and mediastinal (N2) lymph nodes is usually the common method.8 However, dissection of lymph nodes without metastasis might be futile, and might also increase perioperative complications or prolong surgery time.9, 10 Selective lymph node dissection was therefore argued to be more suitable than the systematic procedure in elderly patients with early‐stage disease.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Understanding of patient demographic and tumor biological characteristics is critical for matching appropriate patients with individualized surgical procedures and forecasting patient prognoses.

The aim of this observational study is to collect real‐world data on the clinical characteristics of the Chinese T1 NSCLC patients with lymph node metastases and explore potential factors that predict lymph node metastases in the target population, which might help with individualized surgical plans.

Methods

Patient population

This multicenter real‐world observational study in China included pathologically established T1 NSCLC patients from 10 participating hospitals. The clinical and pathological information of patients was collected with the assistance of the Large‐scale Data Analysis Center of Cancer Precision Medicine‐LinkDoc database. All patients underwent segmentectomy or lobectomy with lymph nodes resection during a period from 2 January 2014 to 27 December 2017. Patients receiving chemotherapies, radiotherapies, biotherapies, or intervention therapies before surgery were excluded, as well as those who underwent lung wedge resection.

Data evaluation

Clinical and pathological information, including age, sex, pathological type, lymph node metastases, tumor size, location, differentiation, smoking history, preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, and vascular invasion, were retrospectively collected from 10 thoracic surgery centers. The study data were retrospectively reviewed and collected for: (i) the risk factors associated with lymph node metastases; and (ii) comparison of the percentages of patients with lymph node metastases. Patient diagnosis was according to the classifications of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and surgical approaches at the surgeons’ discretion. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee at all 10 sites, and was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov before the study was initiated (NCT03413956).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard. Categorical variables are presented as the frequency and percentage. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out to examine the risk factors associated with lymph node metastases. Results are summarized as odds ratios (ORs) and two‐side 95% confidential intervals (CIs). All variables with significant associations (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model. In addition, in view of the significant association of age with N2 lymph node metastasis in NSCLC or T1 NSCLC reported previously, it was also included into the multivariate analysis.17, 18 All variables with P ≤ 0.2 were retained in the final model. All statistical analyses were two‐sided, and were carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics and lymph node metastases of the patients

This study included a total of 10 885 patients who had pathological T1 (tumor size between 0 and 3 cm) NSCLC between 2014 and 2017 from 10 hospitals in China. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the patients, 5265 were men (48.4%) with a median age of 60 years (range 12.9–86.6 years). A total of 458 patients were documented to have lymph node metastases preoperatively. On pathological diagnosis, 1808 patients (16.6%) were shown to have lymph node metastases. A total of 640 patients (5.9%) had metastasis in pulmonary lymph nodes (N1, 516 single N1 and 124 Multiple N1), and 1159 patients (10.6%) had metastases in mediastinal nodes with or without pulmonary lymph nodes (N2, 618 single N2 and 541 multiple N2, 405 skip N2). Most patients (n = 9077, 83.4%), however, had no metastasis in lymph nodes (N0). Patients were divided into those who were aged ≥65 years and those who were aged <65 years. A total of 71.6% (n = 7797) of the patients were aged >65 years. Some 3260 patients (29.9%) were current or former smokers, 7363 patients (67.6%) were never smokers, and 262 (2.5%) patients did not provide this information. Of all the patients included, 8309 (76.6%) patients had a Brinkman Index ≤400, and 2039 (18.7%) >400. The index was scored as the number of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years since smoking started. The tumor histology of patients consisted of adenocarcinoma (AD) in 9216 (84.7%), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 1271 (11.7%), and other pathological types in 398 (3.6%) patients. The number of patients with poorly‐, moderately‐, and well‐differentiated NSCLC were 6544 (60.1%), 820 (7.5%), and 3521 (32.3), respectively. A total of 6544 (60.1%) tumors were located in the upper lobe, 820 (7.5%) in the middle lobe, and the remaining 3521 (32.3%) were in the lower lobe. The details of tumor location are shown in Table 1. Pathological tumor size was divided into three groups according to T1 staging of lung cancer (T1a, T1b, T1c), and the number of patients in each group was 2779 (25.5%), 4766 (43.8%), and 3340(30.7%), respectively. Preoperative plasma CEA level was measured in 6564 of the patients. A total of 5560 patients (51.1%) showed <5 ng/mL, and the other 1004 (9.2%) patients showed >5 ng/mL. The patients with or without vascular invasion were 381 (3.5%) and 10 488 (96.4%), respectively.

Table 1.

Demographics and tumor characteristics of patients with T1 non‐small cell lung cancer

| Variable | T1 non‐small cell lung cancer | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | pN0 (%) | pN+ (%) | ||

| All patients | 10 885 (100%) | 9077 (83.4%) | 1808 (16.6%) | |

| Age | 0.5646† | |||

| ≤65 years | 7797 (71.6%) | 6512 (71.7%) | 1285 (16.5%) | |

| >65 years | 3088 (28.4%) | 2565 (28.3%) | 523 (16.9%) | |

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 5265 (48.4%) | 4207 (46.3%) | 1058 (20.1%) | |

| Female | 5620 (51.6%) | 4870 (53.7%) | 750 (13.3%) | |

| Smoking history | <0.0001 | |||

| Never smoke | 7363 (67.6%) | 6365 (71.8%) | 998 (13.6%) | |

| Ever smoke | 3260 (29.9%) | 2497 (28.2%) | 763 (23.4%) | |

| Unknown | 262 (2.5%) | – | – | |

| Brinkman index‡ | <0.0001 | |||

| ≤400 | 8309 (76.6%) | 7098 (82.2%) | 1211 (14.6%) | |

| >400 | 2039 (18.7%) | 1533 (17.8%) | 506 (24.6%) | |

| Unknown | 537 (4.7%) | – | – | |

| Tumor histology | <0.0001 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 9216 (84.7%) | 7916 (87.2%) | 1300 (14.1%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1271 (11.7%) | 885 (9.7%) | 386 (30.4%) | |

| Others | 398 (3.6%) | 276 (3.0%) | 122 (6.7%) | |

| Tumor grade | <0.0001 | |||

| Poor differentiation | 1765 (16.2%) | 1126 (24.5%) | 639 (36.2%) | |

| Moderate differentiation | 3180 (29.2%) | 2747 (59.7%) | 433 (13.6%) | |

| Well differentiation | 742 (6.8%) | 727 (15.8%) | 15 (2.0%) | |

| Tumor location3 | 0.0099 | |||

| Upper lobe | 6544 (60.1%) | 5505 (60.6%) | 1039 (15.9%) | |

| Middle lobe | 820 (7.5%) | 691 (7.6%) | 129 (15.7%) | |

| Lower lobe | 3521 (32.3%) | 2881 (31.7%) | 640 (18.2%) | |

| Tumor location2 | 0.0008 | |||

| Left lobe | 4508 (41.4%) | 3695 (40.7%) | 813 (18.0%) | |

| Right lobe | 6377 (58.6%) | 5382 (59.3%) | 995 (15.6%) | |

| Tumor location5 | 0.0003 | |||

| Left upper lobe | 2887 (26.5%) | 2378 (26.2%) | 509 (17.6%) | |

| Left lower lobe | 1621 (14.9%) | 1317 (14.5%) | 304 (18.8%) | |

| Right upper lobe | 3657 (33.6%) | 3127 (34.4%) | 530 (14.5%) | |

| Right middle lobe | 820 (7.5%) | 691 (7.6%) | 129 (15.7%) | |

| Right lower lobe | 1900 (17.5%) | 1564 (17.2%) | 336 (17.7%) | |

| Tumor size (pathological) | <0.0001 | |||

| >0 and ≤1 cm | 2779 (25.5%) | 2682 (29.5%) | 97 (3.5%) | |

| >1 and ≤2 cm | 4766 (43.8%) | 4110 (45.3%) | 656 (13.8%) | |

| >2 and ≤3 cm | 3340 (30.7%) | 2285 (25.2%) | 1055 (31.6%) | |

| Preoperative serum CEA level | <0.0001 | |||

| <5 ng/mL | 5560 (51.1%) | 4878 (88.9%) | 682 (12.3%) | |

| ≥5 ng/mL | 1004 (9.2%) | 606 (11.1%) | 398 (39.6%) | |

| Unknown | 4321 (39.7%) | ‐ | ||

| Vascular invasion | <0.0001 | |||

| Positive | 381 (3.5%) | 8870 (97.9%) | 188 (49.3%) | |

| Negative | 10 488 (96.4%) | 193 (2.1%) | 1618 (15.4%) | |

| Unknown | 16 (0.1%) | ‐ | ‐ | |

Bold values (P < 0.05) indicate statistical significance.

χ2‐test.

Scored as the number of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years since smoking started.

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

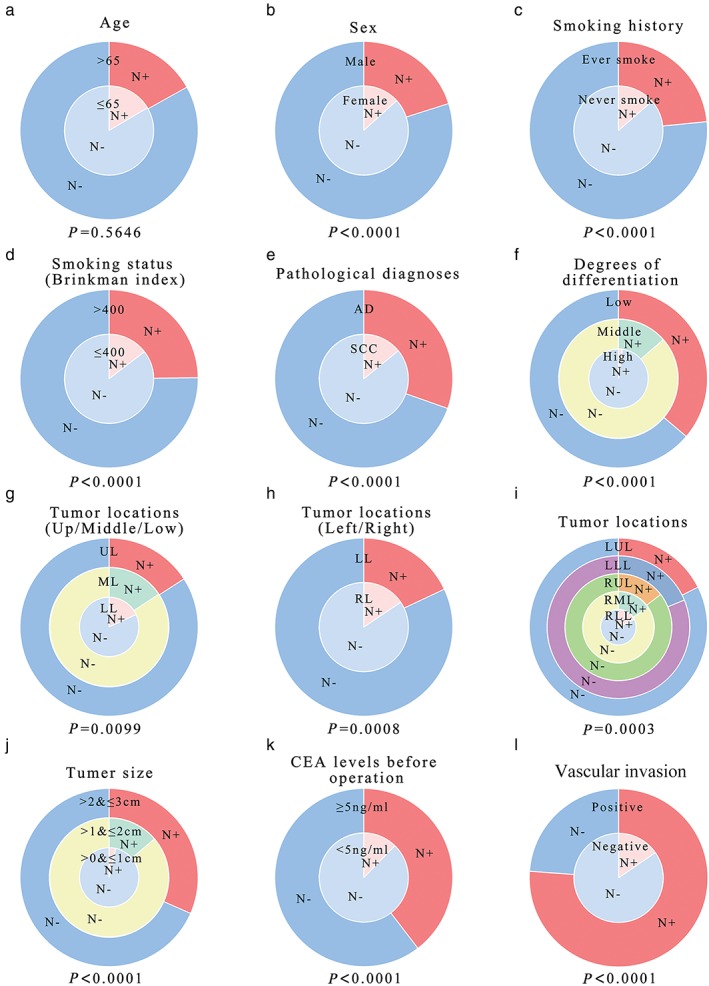

Table 1 and Figure 1 also show the percentage of patients with lymph node metastasis under different variables. Some variables were found as significant predictors for lymph nodal metastasis after univariate analysis. Male smokers with a Brinkman Index >400 were more likely to develop lymph nodal metastasis. In addition, lung SCC (P < 0.0001), larger tumor size (>2 and ≤3 cm vs. >0 and ≤1 cm; >1 and ≤2 cm vs. >0 and ≤1 cm, P < 0.0001), poor tumor differentiation (P < 0.0001), and preoperative serum CEA level of ≥5 ng/mL (P < 0.0001) were identified as significant predictors.

Figure 1.

Probability of lymph node metastasis in T1 non‐small cell lung cancer with different clinical and tumor characteristics. (a) Age, (b) sex, (c) smoking history, (d) smoking status, (e) pathological diagnosis, (f) degrees of differentiation, (g–i) tumor locations, (j) tumor size, (k) preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level, and (l) vascular invasion are included.

Independent risk factors for lymph nodal metastasis

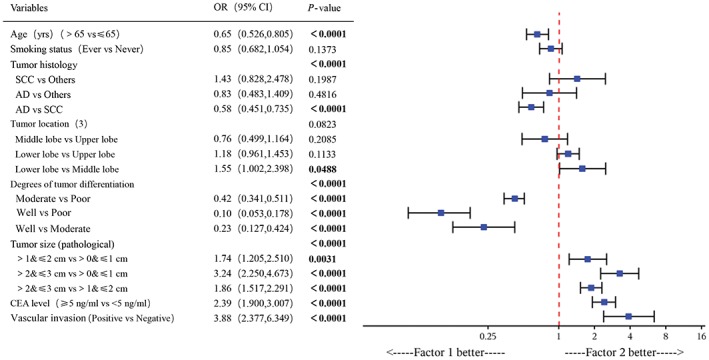

After eliminating cases with missing data to further optimize the study population, multivariate analysis of the remaining 3130 patients revealed the following variables as independent risk factors for lymph nodal metastasis: (i) age >65 years (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.526–0.805, P < 0.0001); (ii) tumor histology of AD (vs. SCC, OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.451–0.735, P < 0.0001); (iii) moderate or poor tumor differentiation (vs. well differentiated, OR 0.42, 0.10, 95% CI 0.341–0.511, 0.053–0.178, P < 0.0001); (vi) larger (>2 and ≤3 cm, and >1 and ≤2 cm) pathological tumor size (vs. >0 and ≤1 cm, OR 1.74, 3.24, 95% CI 1.205–2.510, 2.250–4.673, P = 0.0031 and P < 0.0001); (v) preoperative serum CEA level ≥5 ng/mL (vs. <5 ng/mL, OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.900–3.007, P < 0.0001); and (vi) vascular invasion (OR 3.88, 95% CI 2.377–6.349, P < 0.0001; Fig 2). Of note, the age of the patient was identified as an independent risk factor according to multivariate analysis, although there was no significant difference in univariate analysis (Fig 2; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Multivariate analyses of risk factors of N2 lymph node metastases.

Subgroup analysis of lymph node metastasis

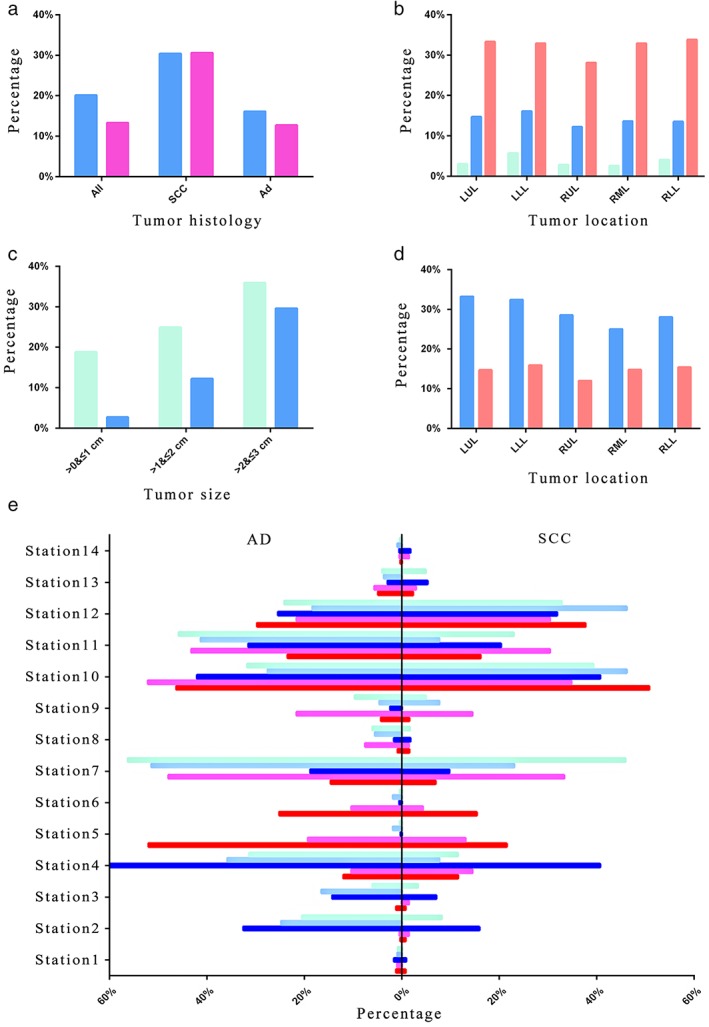

Regarding different pathological types, the lymph node metastasis rate was of great difference between men and women. A total of 16.1% of male patients (610/3784) with lung AD were observed with lymph node metastasis, significantly larger than that of their female counterparts (12.7%, 690/5432, P = 0.0007). In patients with lung SCC, however, the lymph node metastasis rate was similar regardless of sex, 30.4% and 30.6% of patients (367/1209, 19/62) had lymph node metastasis in male and female patients, respectively (Table 2; Fig 3a).

Table 2.

Lymph node metastasis in male and female patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma

| Male (5265) | Female (5620) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | |||

| No. patients | 3784 | 5432 | 0.0007 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 610 (16.1%) | 690 (12.7%) | |

| Lymph node negative (%) | 3174 (83.9%) | 4742 (87.3%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |||

| No. patients | 1209 | 62 | 0.9128 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 367 (30.4%) | 19 (30.6%) | |

| Lymph node negative (%) | 842 (69.6%) | 43 (69.4%) | |

Bold values (P < 0.05) indicate statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of lymph node metastasis. (a) Lymph node metastasis in patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of different sexes.  , Male;

, Male;  , Female. (b) Lymph node metastasis of different stages of non‐small cell lung cancer in different lung lobes.

, Female. (b) Lymph node metastasis of different stages of non‐small cell lung cancer in different lung lobes.  , >0&≤1 cm;

, >0&≤1 cm;  , >1&≤2 cm;

, >1&≤2 cm;  , >2&≤3 cm. (c) Lymph node metastasis in patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of different stages.

, >2&≤3 cm. (c) Lymph node metastasis in patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of different stages.  , SCC;

, SCC;  , AD. (d) Different tumor histology of lymph node metastasis in different lung lobes.

, AD. (d) Different tumor histology of lymph node metastasis in different lung lobes.  , SCC;

, SCC;  , AD. (e) Lymph node metastasis to various stations of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in different lung lobes.

, AD. (e) Lymph node metastasis to various stations of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in different lung lobes.  , LUL;

, LUL;  , LLL;

, LLL;  , RUL;

, RUL;  , RML;

, RML;  , RLL. AD, adenocarcinoma; LUL, left upper lobe; LLL, left lower lobe; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right lower lobe; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

, RLL. AD, adenocarcinoma; LUL, left upper lobe; LLL, left lower lobe; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right lower lobe; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

When grouping patients by pathological tumor size, the probability of lymph node metastasis varied with tumor location. As the size increased, the probability of lymph node metastasis increased irrespective of lobe location of tumors. In T1a‐T1b NSCLC patients, tumors in the left lower lobe had the highest probability of lymph node metastasis (5.7%, 16.1%). Tumors in the right upper lobe were almost the least prone to have lymph node metastasis in each size subgroup (2.8%, 12.2%, 28.1%). The metastasis rate exceeded one‐third when the tumor size was >2 cm (T1c; Fig 3b).

Different tumor sizes were also compared under different pathological types. There was a significant difference in lymph node metastasis rates between all sizes in both pathological types. For all tumor sizes, lymph node metastasis of SCC was more common than that of AD. The probability of lymph node metastasis in AD was <3% when the tumor size was ≤1 cm (Fig 3c). The details can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Lymph node metastasis in patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of different stages

| >0 and ≤1 cm (T1a) | >1 and ≤2 cm (T1b) | >2 and ≤3 cm (T1c) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | |||

| No. patients | 2632 | 4143 | 2441 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 71 (2.7%) | 506 (12.2%) | 723 (29.6%) |

| Lymph node negative (%) | 2561 (97.3%) | 3637 (87.8%) | 1718 (70.4%) |

| OR, P‐value | |||

| vs. >0 and ≤ 1 cm | 5.02, <0.0001 | 15.17, <0.0001 | |

| vs. >1 and ≤ 2 cm | 3.02, <0.0001 | ||

| Squamous‐cell carcinoma | |||

| No. patients | 117 | 461 | 693 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 22 (18.8%) | 115 (24.9%) | 249 (35.9%) |

| Lymph node negative (%) | 95 (81.2%) | 346 (75.1%) | 444 (64.1%) |

| OR, P‐value | |||

| vs. >0 and ≤ 1 cm | 1.44, 0.1645 | 2.42, 0.0004 | |

| vs. >1 and ≤ 2 cm | 1.69, <0.0001 | ||

Bold values (P < 0.05) indicate statistical significance.

Lung SCC and AD in each lung lobe were also compared. Lung cancer was most common in the right upper lobe, but the probability of lymph node metastasis was one of the lowest (12.0%, 28.5%). Lymph node metastasis was most likely to occur in the left lower lobe of lung AD, and the trend of lymph node metastasis in different lobes of SCC was: LUL > LLL > RUL > RLL > RML (Table 4; Fig 3d). For two pathological types, the information of lymph node transferred to each station can be seen in Figure 3e, and the tumors in each lobe are shown separately. Patients with SCC were more prone to have N1 lymph node metastasis, whereas AD patients had more N2 lymph node metastasis.

Table 4.

Different tumor histology of lymph node metastasis in different lung lobes

| LUL | LLL | RUL | RML | RLL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||

| No. patients | 2380 | 1341 | 3148 | 735 | 1612 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 350 (14.7%) | 213 (15.9%) | 379 (12.0%) | 109 (14.8%) | 249 (15.4%) |

| Lymph node negative (%) | 2030 (85.3%) | 1128 (84.1%) | 2769 (88.0%) | 626 (85.2%) | 1363 (84.6%) |

| P‐value | 0.0013 | ||||

| OR, P‐value | |||||

| vs. Left upper lobe | 1.10, 0.3358 | 0.79, 0.0038 | 1.01, 0.9339 | 1.06, 0.5202 | |

| vs. Left lower lobe | 0.72, 0.0005 | 0.92, 0.5259 | 0.97, 0.7447 | ||

| vs. Right upper lobe | 1.27, 0.0403 | 1.33, 0.0010 | |||

| vs. Right middle lobe | 1.05, 0.6999 | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |||||

| No. patients | 391 | 213 | 397 | 52 | 218 |

| Lymph node metastasis (%) | 130 (33.2%) | 69 (32.4%) | 113 (28.5%) | 13 (25.0%) | 61 (28.0%) |

| Lymph node negative (%) | 261 (66.8%) | 144 (67.6%) | 284 (71.5%) | 39 (75.0%) | 157 (72.0%) |

| P‐value | 0.4178 | ||||

Bold values (P < 0.05) indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

As is reported, lymph node status, especially pathological status, is of great significance, for prognosis as well as guiding postoperative therapeutic strategy in NSCLC.19 Lymph node dissection is often indicated and is indeed essential, especially during surgery for cT1a‐2bN0‐1M0 NSCLC patients.20 Although lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection has been globally accepted as a standard procedure for resectable primary NSCLC,21 arguments still came out that systematic dissection of lymph nodes without tumor cells might be futile and may also increase perioperative complications or prolong surgery time.9, 10 Selective lymph node dissection might be more suitable, but a better understanding of lymph node metastasis is indispensable. Unfortunately, there has not been a large retrospective study to explore the characteristics of lymph node metastasis in patients with early‐stage lung cancer in China. Our study was designed to understand the clinical characteristics of the Chinese target population, so as to determine the risk factors for lymph node metastases in real‐world practice. The findings of our study might help to guide clinical patient management as complementary evidence to the randomized clinical trials.

Approximately 8.3–15.9% of patients with clinical stage I NSCLC have been subsequently shown to have lymph node metastasis.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 The metastasis rate of our experimental group was 16.6%, consistent with the reports in the literature. Within the 10 885 patients with T1 NSCLC from 10 different prestigious hospitals, most (71.6%) patients were aged <65 years. However, male patients with NSCLC were more likely to develop lymph node metastasis than women.

According to our results, patient demographic characteristics (sex, smoking history/status), and tumor biological characteristics (tumor histology, degrees of differentiation, tumor location, size, preoperative serum CEA levels, and status of vascular invasion) were shown to influence lymph node metastasis in the univariate analyses, whereas age, tumor histology, degrees of differentiation, size, CEA levels, and status of vascular invasion were presented as the independent risk factors by the multivariate analyses.

Previous studies showed age as an independent predictor of N2 lymph node metastasis in NSCLC or those with T1 disease.17, 18 In our study, it was not found to be a relevant factor for nodal involvement in univariate analysis (P = 0.56), which was also observed in the study by Fuwa et al. 27 According to multivariate analysis, however, age seemed to be an independent risk factor (OR 0.65, P < 0.0001), which means younger patients were more prone to having lymph node metastases. There was no statistical difference between AD and SCC in the light of the study by Yu et al. 28 However, in our study, we found that patients with tumor histology of SCC were much more likely to have lymph node metastases (30.4%) compared with AD patients.

Tumor size is considered one of the important risk factors for lymph node metastasis according to univariate and multivariate analysis, and can be detected by preoperative radiology.29 Zhang et al. showed a prevalence of lymph node metastasis of 7.4% in tumors 1–2 cm, and 3.8% in tumors <1 cm.30 In our study, 97 of 2779 patients (3.5%) had pathological lymph node metastases of tumors 0–1 cm, and 656 of 4766 patients (13.8%) had lymph node metastases of tumors 1–2 cm; whereas in the patients with tumor size 2–3 cm, the percentage of lymph node metastases increased to 31.6% (1055/3340). These findings indicated an increasing tendency of lymph node metastases with the increased tumor size. Our data support the work of Asamura et al., which showed a significant association between increasing tumor size and higher incidences of lymph node metastasis.31

Serum CEA level has long been established to be associated with lymph node metastases in NSCLC patients.32, 33 According to Suzuki et al., lymph node metastasis occurred significantly more frequently in cases with a high CEA value than those with a normal value.34 The results of our study showed the same conclusion that preoperative serum CEA level is another significant risk factor. In patients with a normal CEA value, the rate of lymph node metastases was 12.3%, significantly lower than those with a high CEA value (39.6%), suggesting that serum CEA level might act as an indication to carry out more aggressive lymph node dissection.

Our results also suggested that tumor differentiation and vascular invasion were the other two independent risk factors for lymph node metastasis in T1 NSCLC. Well‐differentiated cases occupied the smallest proportion, with the lymph node metastases rate of just 2%. In contrast, in patients with moderately and poorly differentiated tumors, the lymph node metastasis rate reached 13.6% and 36.2%, respectively (P < 0.0001). The status of vascular invasion was associated with a greater tendency for lymph node metastases, with the highest ORs (3.88, P < 0.0001) in univariate and multivariate logistic analyses. The same conclusion was reached in the study of Sung et al. 35 Analysis of the reason might be that the worse the tumor differentiation is, the stronger the invasiveness would be, which leads to early metastasis. The status of vascular invasion suggests that tumor cells invade and migrate along surrounding tiny blood vessels or lymphatic vessels, which might cause early metastasis and poor prognosis. Although these two factors cannot be clearly defined before surgery, the detection of tumor differentiation and vascular invasion in the pathological results of postoperative disease might help to predict the prognosis of patients with early‐stage NSCLC.

In our subgroup analysis, most female patients with AD had a smaller percentage of lymph node metastases compared with male AD patients (P = 0.0007). However, the rate of metastasis in patients with SCC was much greater, and there is no significant difference between men and women. Our results suggest that left lower lung cancer was more likely to have lymph node metastases in patients with tumor size of ≤2 cm. Patients with SCC had a much higher percentage of lymph node metastases irrespective of tumor size. Also, as the tumor size increased, the proportion of patients with lymph node metastases increased gradually in both lung SCC and AD.

Results from others’ studies suggest that non‐upper lobe‐located tumors had a tendency toward a higher incidence of lymph node metastases.18, 30, 32 According to multivariate analysis of our study, lobe distribution of tumors was not a significant predictor for lymph node metastases, but subgroup analysis showed that the incidences of lymph node metastases were significantly different between the right upper lobe and left lower lobe (P = 0.0005).

This study was limited by the constraints of a retrospective study with the inherent bias, such as patient selection, preoperative clinical and invasive staging modalities, and heterogeneity of treatment approaches. A prospectively collected database with predefined clinical parameters, investigation modalities, and treatment approaches might be helpful in clarifying the findings observed in this retrospective observational study.

In conclusion, the real‐world clinical study data offered solid guidance on the assessments of clinical characteristics of the target patients and patient management in clinical practice: in the Chinese T1 NSCLC patients with lymph node metastases, the clinical characteristics were defined and similar patient profiles were observed, as compared with the other studies. The percentages of lymph node metastases were shown to be associated with sex, smoking history/status, tumor histology, degrees of differentiation, tumor location, size, preoperative serum CEA levels, and status of vascular invasion, whereas age, tumor histology, degrees of differentiation, size, CEA levels, and status of vascular invasion were presented as the independent risk factors. Female patients with T1a AD barely had lymph node metastasis, especially in the right upper lobe. However, whether omission of systematic lymph node dissection may be considered is still difficult to say. Further studies should be carried out to evaluate the need for lymph node sampling in this patient subgroup. Our study might offer some clues to preoperative assessment of lymph node metastasis in T1 NSCLC, which could help to provide optimal care for operable NSCLC patients.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest..

Acknowledgment

The study database was developed by LinkDoc (Beijing) Technology Co. Ltd.

Contributor Information

Lin Xu, Email: szl_xl@126.com.

Feng Jiang, Email: zengnljf@hotmail.com.

References

- 1. Xiong J, Wang R, Sun Y, Chen H. Lymph node metastasis according to primary tumor location in T1 and T2 stage non‐small cell lung cancer patients. Thoracic Cancer 2016; 7 (3): 304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jemal A, Bray F, Center M, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61 (2): 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patz EF Jr, Goodman PC, Bepler G. Screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2000; 343 (22): 1627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J et al The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11 (1): 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Conces DJ Jr, Klink JF, Tarver RD, Moak GD. T1N0M0 lung cancer: Evaluation with CT. Radiology 1989; 170 (3 Pt 1): 643–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heavey LR, Glazer GM, Gross BH, Francis IR, Orringer MB. The role of CT in staging radiographic T1N0M0 lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986; 146 (2): 285–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung K, Lee K, Kim H et al T1 lung cancer on CT: Frequency of extrathoracic metastases. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2000; 24 (5): 711–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non‐small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 60 (3): 615–22; discussion 22‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lardinois D, Suter H, Hakki H, Rousson V, Betticher D, Ris HB. Morbidity, survival, and site of recurrence after mediastinal lymph‐node dissection versus systematic sampling after complete resection for non‐small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2005; 80 (1): 268–74; discussion 74‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okada M, Sakamoto T, Yuki T, Mimura T, Miyoshi K, Tsubota N. Selective mediastinal lymphadenectomy for clinico‐surgical stage I non‐small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 81 (3): 1028–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ishiguro F, Matsuo K, Fukui T, Mori S, Hatooka S, Mitsudomi T. Effect of selective lymph node dissection based on patterns of lobe‐specific lymph node metastases on patient outcome in patients with resectable non‐small cell lung cancer: A large‐scale retrospective cohort study applying a propensity score. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 139 (4): 1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aokage K, Yoshida J, Ishii G, Hishida T, Nishimura M, Nagai K. Subcarinal lymph node in upper lobe non‐small cell lung cancer patients: Is selective lymph node dissection valid? Lung Cancer 2010; 70 (2): 163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Y, Wu N, Chen J et al Is radical mediastinal lymphadenectomy necessary for elderly patients with clinical N‐negative non‐small‐cell lung cancer? A single center matched‐pair study. J Surg Res 2015; 193 (1): 435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma W, Zhang ZJ, Li Y, Ma GY, Zhang L. Comparison of lobe‐specific mediastinal lymphadenectomy versus systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy for clinical stage T(1)a N(0) M(0) non‐small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Ther 2013; 9 (Suppl 2): S101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Darling GE, Allen MS, Decker PA et al Randomized trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in the patient with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non‐small cell carcinoma: Results of the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 141 (3): 662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma K, Chang D, He B et al Radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy versus mediastinal lymph node sampling in patients with clinical stage IA and pathological stage T1 non‐small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2008; 134 (12): 1289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shafazand S, Gould MK. A clinical prediction rule to estimate the probability of mediastinal metastasis in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2006; 1 (9): 953–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Y, Sun Y, Xiang J, Zhang Y, Hu H, Chen H. A prediction model for N2 disease in T1 non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 144 (6): 1360–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lardinois D, De Leyn P, Van Schil P et al ESTS guidelines for intraoperative lymph node staging in non‐small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardio‐Thoracic Surg 2006; 30 (5): 787–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adachi H, Sakamaki K, Nishii T et al Lobe‐specific lymph node dissection as a standard procedure in surgery for non‐small cell lung cancer: A propensity score matching study. J Thorac Oncol 2017; 12 (1): 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cahan W. Radical lobectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1960; 39: 555–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D'Cunha J, Herndon J, Herzan D et al Poor correspondence between clinical and pathologic staging in stage 1 non‐small cell lung cancer: Results from CALGB 9761, a prospective trial. Lung Cancer 2005; 48 (2): 241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Veeramachaneni N, Battafarano R, Meyers B, Zoole J, Patterson G. Risk factors for occult nodal metastasis in clinical T1N0 lung cancer: A negative impact on survival. Eur J Cardio‐Thorac Surg 2008; 33 (3): 466–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Park H, Jeon K, Koh W et al Occult nodal metastasis in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer at clinical stage IA by PET/CT. Respirology 2010; 15 (8): 1179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li L, Ren S, Zhang Y et al Risk factors for predicting the occult nodal metastasis in T1‐2N0M0 NSCLC patients staged by PET/CT: Potential value in the clinic. Lung Cancer 2013; 81 (2): 213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cho S, Song I, Yang H, Kim K, Jheon S. Predictive factors for node metastasis in patients with clinical stage I non‐small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96 (1): 239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fuwa N, Mitsudomi T, Daimon T et al Factors involved in lymph node metastasis in clinical stage I non‐small cell lung cancer‐‐from studies of 604 surgical cases. Lung Cancer 2007; 57 (3): 311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu X, Li Y, Shi C, Han B. Risk factors of lymph node metastasis in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer </= 2 cm in size: A monocentric population‐based analysis. Thoracic Cancer 2018; 9 (1): 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bao F, Yuan P, Yuan X, Lv X, Wang Z, Hu J. Predictive risk factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with small size non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2014; 6 (12): 1697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang Y, Sun Y, Shen L et al Predictive factors of lymph node status in small peripheral non‐small cell lung cancers: Tumor histology is more reliable. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20 (6): 1949–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Asamura H, Nakayama H, Kondo H, Tsuchiya R, Shimosato Y, Naruke T. Lymph node involvement, recurrence, and prognosis in resected small, peripheral, non‐small‐cell lung carcinomas: Are these carcinomas candidates for video‐assisted lobectomy? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 111 (6): 1125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koike T, Koike T, Yamato Y, Yoshiya K, Toyabe S. Predictive risk factors for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in clinical stage IA non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7 (8): 1246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grunnet M, Sorensen JB. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumor marker in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2012; 76 (2): 138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suzuki K, Kusumoto M, Watanabe S, Tsuchiya R, Asamura H. Radiologic classification of small adenocarcinoma of the lung: Radiologic‐pathologic correlation and its prognostic impact. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 81 (2): 413–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sung SY, Kwak YK, Lee SW et al Lymphovascular invasion increases the risk of nodal and distant recurrence in node‐negative stage I‐IIA non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Oncology 2018; 95 (3): 156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]