Abstract

Aims and Objectives:

To assess the effectiveness of chitosan-based dressing after extraction in individuals on antithrombotics, without modification of their treatment schedule.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized comparative study was carried out on 40 subjects who had two extraction sites, in dissimilar quadrants. The surgical site was chosen at random and post-extraction hemostasis was achieved by a custom-cut chitosan dressing (study site) and sterile cotton gauze dressing (suturing if required) at control site. Patients were reviewed on the first, third, fifth, and seventh postoperative days and every week till 4 weeks. The parameters assessed were timing of hemostasis, pain scores, and pus discharge.

Results:

Out of 40 study subjects, 24 (60%) were males and 16 (40%) were females. The age was 40–65 years (mean age 54 years). The mean time for hemostasis was 0.63 ± 0.27 min in study group, whereas for controls, it was 9.10 ± 2.28 min. The difference in postoperative pain was significant (P = 0.001) on days one, five, and seven. In chitosan group extraction sites, dry socket was not seen, whereas four patients on day three and five patients on day five after extraction experienced dry socket in pressure gauze dressings group, with an insignificant difference (P = 0.058). In chitosan group extraction sites, no pus discharge was seen. Whereas four patients on days three and five after extraction had pus discharge in patients where pressure dressings were applied, with an insignificant difference (P = 0.058).

Conclusion:

Chitosan dressing is a competent hemostatic agent that significantly reduced the post-extraction bleeding, with better pain control. Chitosan group had no incidences of dry socket and pus discharge.

KEYWORDS: Chitosan, myocardial infarction, oral antithrombotic drugs, post- extraction bleeding, thromboembolism

INTRODUCTION

Oral surgeons usually encounter patients taking oral antithrombotic (OAT) drugs requiring removal of teeth. Excessive bleeding is a mainly seen and most challenging complication in such patients.[1] In such instances, oral surgeons have two options, either to stop OAT drugs thereby risking thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular accidents or continuing drugs thereby risking uncontrolled bleeding.[2] Hence, a prudent surgeon must consider the risk of postoperative bleeding against thromboembolism in such patients.[3,4]

Local measures used for hemostasis include pressure application by gauze, oxidized cellulose, tranexamic acid mouthwash, absorbable gelatin, suturing, etc.[1] An ideal hemostatic agent must be safe, bacteriostatic, and cost-effective.[5]

Chitosan is a naturally occurring, biocompatible polysaccharide, which activates coagulation pathway. Due to its positive charge, chitosan pulls red blood cells and platelets towards it (negative charge), thereby forming a strong seal at wound site. The initial seal gets further strengthened by continuous accumulation of platelets and red blood cells, achieving hemostasis.[6,7,8]

Advantages of chitosan are its self-adhesive nature and ability to be placed even on actively bleeding surface and in hemophilic patients. It prevents wound from getting exposed to outside environment, and release of residual acetic acid has shown to reduce pain.[2,4]

We carried our study in subjects on OAT undergoing extractions, to assess the efficiency of chitosan-based hemostatic dressing in post-extraction bleeding and pain control and its role in healing of extraction wound, as judged against conventional methods such as pressure dressings like gauze.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty patients on OAT reporting to oral and maxillofacial surgery department were chosen randomly for this study. Sample size was calculated using G*Power software. Total sample size obtained was 34, which was rounded to 40. Extractions were performed without alteration in their antithrombotic medication regimen. We obtained institutional ethical clearance (GDCH/EC12/2016) and informed consent from the subjects. The following were the inclusion criteria:

Patients on OAT undergoing extraction

Patients aged between 35 and 75 years

Patients having two extraction sites, one in separate quadrant, so as to have both study and control sites

Patients having international normalized ratio (INR) values ≤3 (i.e. 1–3)

The following were the exclusion criteria:

Patients with allergy to sea foods, because chitosan-based dressing is manufactured from freeze-dried chitosan, derived from shrimp shell chitin

Patients with only one surgical site, i.e., lacking internal control site

Patients having genetic bleeding disorders

Patients having extraction sites in the same quadrant

Hematological investigations (complete blood picture, clotting time, bleeding time, random blood sugar, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, prothrombin time, INR, and platelet count) were carried out in all subjects.

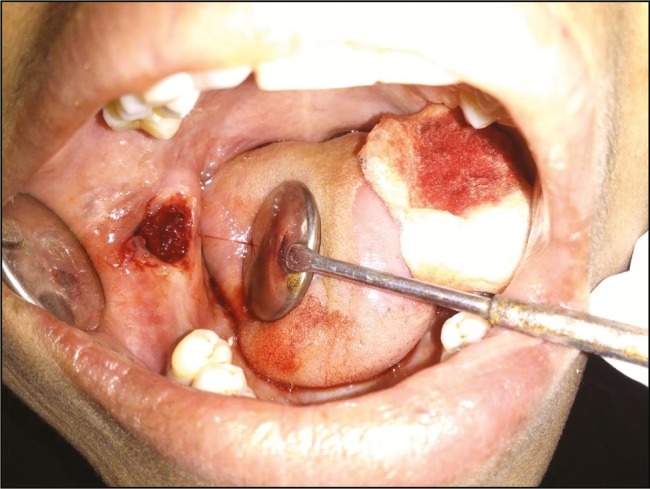

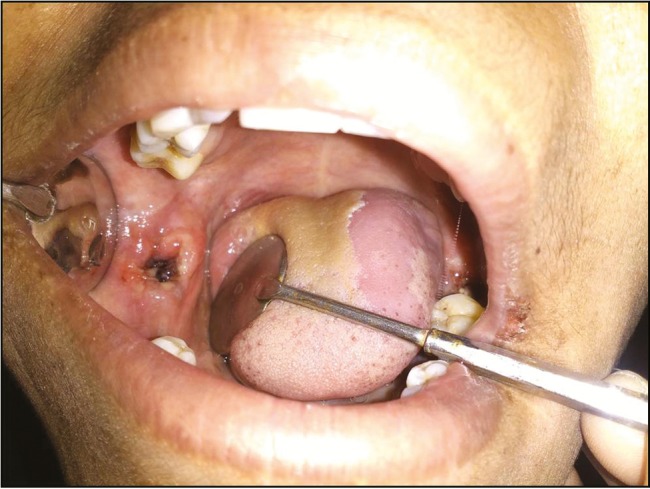

To reduce any study variability, similar contralateral or counterpart teeth were removed. Atraumatic surgical extractions were carried out under local anesthesia [Figure 1]. The surgical site was randomly chosen for management either by a custom-cut chitosan dressing (study site) or a sterile cotton gauze (control site). Trimmed chitosan dressing material was prepared so as to fit loosely into the extraction sockets, at the height of crestal bone, wherever possible. After placement, finger pressure was applied over the chitosan dressing for 40–60 s. Suturing was performed in the extraction wounds where hemostasis was not attained with sterile gauze piece, even after 15 min. All the subjects were given amoxicillin 500 mg/TID/5 days and Diclomol/TID/3 days. Patients were reviewed on the first, third, fifth, and seventh postoperative days and every week till 4 weeks [Figure 2]. The parameters assessed were timing of hemostasis, pain scores, and pus discharge. Healing was assessed based on sinus opening/pus discharge/wound infection, and dry socket.

Figure 1.

Study site immediately after extraction

Figure 2.

Study site 1 week after extraction

Paired simple “t” test, Wilcoxon signed rank test, chi-square test, and one-way analysis of variance were applied for testing the statistical significance, using Statistical Package for Social Services, version 20, for windows software.

RESULTS

Out of 40 subjects, 24 (60%) were males and 16 (40%) were females. The age was between 40 and 65 years (mean age 54 years). The mean time of hemostasis was 0.63 ± 0.27 min in study group, whereas for controls, it was 9.10 ± 2.28 min, difference being statistically significant (P = 0.001: [Table 1]).

Table 1.

Mean and frequency distribution of time taken for hemostasis

| N | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Mean difference | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | 40 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 1.20 | −8.47 | 0.001 |

| Control | 40 | 9.10 | 2.28 | 5.32 | 17.14 |

Both paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used. SD = standard deviation

The frequency distribution of postoperative pain showed significant variation (P = 0.001) on days one, five, and seven [Table 2].

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of postoperative pain

| Case (n = 40) | Control (n = 40) | P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| D 1 | 1.82 | 0.67 | 0 | 3 | 4.32 | 1.47 | 2 | 7 | 0.001 |

| D 3 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

| D 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 0 | 3 | 0.001 |

| D 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 | 0.001 |

| D 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| D 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| D 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

P < 0.05—significant. Both one-way analysis of variance test (between groups at various follow-ups) and Kruskal–Wallis test were used. D = day, SD = standard deviation

In chitosan extraction sites, dry socket was not observed in any of the patients. Whereas four patients on day three and five on day four after extraction, experienced dry socket in pressure gauze dressings group, with an insignificant difference (P = 0.058; [Table 3]). In cases with dry socket, additional treatment was given by placing eugenol dressings.

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of postoperative dry socket

| Cases (n = 40) | Controls (n = 40) | Total (n = 80) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| D 1 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 3 | 40 | 0 | 36 | 4 | 76 | 4 | 0.058 |

| D 5 | 40 | 0 | 36 | 4 | 76 | 4 | 0.058 |

| D 7 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 14 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 21 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 28 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

Chi-square test (one sided) was used. D = Day

In chitosan group extraction sites, pus discharge was not observed in any of the patients. Whereas four patients on days three and five after extraction had pus discharge in pressure dressing sites, with an insignificant difference (P = 0.058; Table 4). In cases where wound infection occurs, additional treatment was given in the form of antibiotics and debridement.

Table 4.

Frequency distribution of postoperative pus discharge

| Cases (n = 40) | Controls (n = 40) | Total (n = 80) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| D 1 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 3 | 40 | 0 | 36 | 4 | 76 | 4 | 0.058 |

| D 5 | 40 | 0 | 36 | 4 | 76 | 4 | 0.058 |

| D 7 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 14 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 21 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

| D 28 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 0 | — |

Chi-square (one sided) was used. D = Day

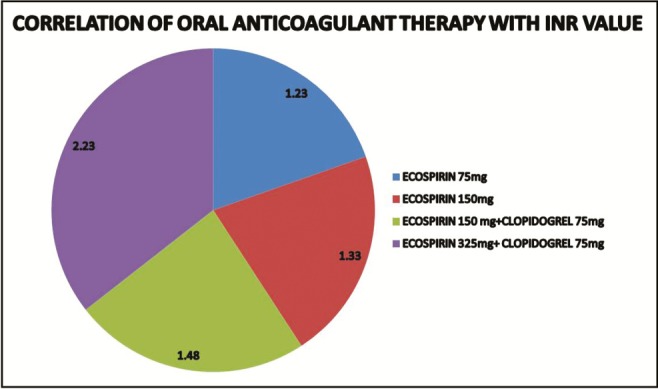

Correlation of OAT therapy with INR value revealed least INR value of 1.23 ± 0.02 in subjects taking Ecosprin 75 mg and highest value 2.23 ± 0.35 in those taking Ecosprin 325 mg + Clopilet 75 mg [Table 5 and [Graph 1].

Table 5.

Correlation of oral anticoagulant therapy with international normalized ratio (INR) value

| Dose (Tab)/OD | N | INR (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Ecosprin 75 mg | 8 | 1.23 ± 0.02 |

| Ecosprin 150 mg | 18 | 1.33 ± 0.05 |

| Ecosprin 150 mg + Clopilet 75 mg | 10 | 1.48 ± 0.13 |

| Ecosprin 325 mg + Clopilet 75 mg | 4 | 2.23 ± 0.35 |

SD = standard deviation, OD = once daily

Graph 1.

Correlation of oral anticoagulant therapy with international normalized ratio (INR) values

DISCUSSION

OAT drugs are given for treatment and prevention of deep vein thromboses, pulmonary emboli, acute ischaemic stroke, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, following joint replacement, major orthopedic trauma, etc.[2,3]

Dentoalveolar surgical procedures are regularly performed on patients taking medications that inhibit platelet aggregation or coagulation mechanisms, such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ticlopidine hydrochloride, dipyridamole, and aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole.[4,5]

Many authors advocated stoppage of OAT for oral surgical procedures. Thorough literature search showed only few patients (approximately 1%) experienced complications after stopping OAT (four died due to thromboembolic complications), but the severe consequences of dental surgery stipulate awareness and intervention. On the other hand, of the surgeries carried out in about 950 patients without stopping OAT drugs, only 12 hemorrhagic complications were reported and were managed without mishap.[9,10,11]

Many studies showed absence of any variation between lowering the dosage of OAT or maintaining OAT dose in patients on whom oral surgical procedures were carried out. But few others suggested either to stop or reduce OAT before procedures.[10,11]

There is strong support that OAT patients undergoing oral surgery must not stop their medication to avoid thromboembolic complications especially in those on long-term antiplatelet medication. But INR must be less than four, local hemostatic measures are of high significance in such instances and there is a need to instruct patients to be careful and monitor any minor bleedings.[11]

We found that the chitosan dressing sites had a better hemostasis than the control sites in all study patients. It attained hemostasis in lesser time than control sites, with reduced pain scores. Chitosan is not a procoagulant that stimulates the normal clotting cascade, thus minimizing the embolism risk.[1,2,4,12]

Malmquist et al.[12] found that chitosan dressing (HemCon Dental Dressing) is a clinically efficient hemostatic agent after oral surgery procedures, even in patients under OAT therapy. They also found a better wound healing and lower pain scores, which were not significant. They used small amount of the chitosan (HemCon) dressing as they noticed that if too much was used or if the socket was fully packed, unreacted residual acetic acid in the chitosan dressing may result in a minor transitory increase in pain scores.[12] This phenomenon was not seen in any of our cases probably due to the little quantity of the material used, and also due to the superficial placing of the dressing material.

We did not altered OAT regimen, believing that thromboembolism risk is more significant than bleeding risk. Even latest studies do not agree with the concept of stopping OAT and recommended prevention of hemorrhagic complications by means of local hemostatic measures, maintaining therapeutic INR levels.[6,7,8,9]

We observed that the quantity of chitosan dressing material needed was rather less owing to its efficient hemostasis. Thus, there was no need to pack the extraction socket fully.

Immediate hemostasis was observed in sites managed with chitosan dental dressing whereas oozing of blood for a brief time was seen in sites treated by pressure dressing alone. This observation highlights the hemostatic effectiveness of chitosan dressing which was in accordance to Pippi et al.[1] and Malmquist et al.[12]

In our study, visual analog scale (VAS) was used to measure pain. We recorded significantly high VAS scores on pressure dressing sites than chitosan sites. The results are in accordance with Pippi et al.[1] and Malmquist et al.,[12] who stated that the mean postoperative pain was significantly less in sites where chitosan-based dressing was used.

The property of chitosan dressing forming an effective barrier that seals off the wound from exposure to environment might be responsible for reduced pain. These results correlate with the clinical findings reported by Malmquist et al.[12]

Four patients suffered with dry socket on pressure sites; however, no patients had dry socket in chitosan group. This is in accordance to Sharma et al.,[8] Eldibany,[10] and Kale et al.[13]

We found a lower incidence of wound infection in chitosan group. Similar observations were reported by other investigators such as Malmquist et al.[12] and Kale et al.[13] Shen et al.[14] found chitosan’s role in platelet aggregation and adhesion and also in growth factor release from platelets. The ability of the chitosan dressing to form an effective seal preventing exposure to external environment and having an inherent bacteriostatic effect might be the two reasons for lowered wound infection. Thus chitosan allows oral surgeons to continue anticoagulant regimens for surgical procedures and obviating the need for comprehensive management of INR status.[14]

The dosage of OAT had a definite bearing on the INR values of the patients, which in turn had a bearing on the clotting time. The patients with 1.6 or higher INR values required considerably longer duration to achieve hemostasis under pressure pack with a sterile gauze piece biting pressure (followed by suturing if required). The chitosan dental dressing was mainly of use in these patients in achieving early hemostasis. Our study results are in accordance with Amer et al.,[15] who found a remarkable increase in the frequency of post-extraction bleeding in patients with INR values >2. However, regarding the adequacy of simple pressure pack in controlling post-extraction bleeding for patients with INR values of either ≤2 or >2, no significant results were noted.[15]

The results of our study reaffirms that chitosan aids in early hemostasis, along with reduced postoperative pain, but the effect of chitosan dressing on wound infection and dry socket was not significant.

Summary of key findings

There was a significantly lower time required for hemostasis in chitosan group.

High VAS scores on pressure dressing sites than chitosan sites were observed.

There was a lower incidence of wound infection in chitosan group.

Limitations

Smaller sample size.

It included only minor oral surgery procedures that had low bleeding risks for patients (simple single tooth extraction).

Patients with an INR of 3 or greater were not included.

Additional studies will be necessary to justify using this therapeutic approach, especially in patients who have higher INRs and in whom major oral surgical procedures are indicated. However, this study proves that chitosan is significantly better in promoting early hemostasis, which can serve the patients on OAT treatment undergoing dental extractions.

CONCLUSION

From the aforementioned observations, it can be concluded that the chitosan dressing was proved to be an effective hemostatic agent that significantly shortens the bleeding time following minor oral surgery procedures in patients on OAT therapy regimens treated without interruption of their therapy. It was also proved to produce considerably enhanced pain control. But occurrence of dry socket and wound infection was not significant result in our study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pippi R, Santoro M, Cafolla A. The use of a chitosan-derived hemostatic agent for postextraction bleeding control in patients on antiplatelet treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:1118–23. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pogorielov MV, Sikora VZ. Chitosan as a hemostatic agent: Current state. Eur J Med. Series B. 2015;2:24–33. Series B. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jimson S, Amaldhas J, Jimson S, Kannan I, Parthiban J. Assessment of bleeding during minor oral surgical procedures and extraction in patients on anticoagulant therapy. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2015;7(Suppl S1):134–7. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.155862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha N, Mazumdar A, Mitra J, Sinha G, Baunthiyal S, Baunthiyal S. Chitosan based Axiostat dental dressing following extraction in cardiac patients under antiplatelet therapy. Int J Oral Health Med Res. 2017;3:65–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santhosh Kumar MP. Dental management of patients on antiplatelet therapy: Literature update. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stricker-Krongrad A-H, Alikhassy Z, Matsangos N, et al. Efficacy of chitosan-based dressing for control of bleeding in excisional wounds. Eplasty. 2018;18:e14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed S, Ikram S. Chitosan based scaffolds and their applications in wound healing. Achi Life Sci. 2016;10:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma S, Kale TP, Balihallimath LJ, Motimath A. Evaluating effectiveness of axiostat hemostatic material in achieving hemostasis and healing of extraction wounds in patients on oral antiplatelet drugs. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18:802–6. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma G. Dental extraction can be performed safely in patients on Aspirin therapy: A timely reminder. ISRN Dent. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/463684. Article ID 463684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eldibany RM. Platelet rich fibrin versus Hemcon dental dressing following dental extraction in patients under anticoagulant therapy. Tanta Dent J. 2014;11:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salam S, Yusuf H, Milosevic A. Bleeding after dental extractions in patients taking warfarin. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:463–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malmquist JP, Clemens SC, Oien HJ, Wilson SL. Hemostasis of oral surgery wounds with the HemCon Dental Dressing. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kale TP, Singh AK, Kotrashetti SM, Kapoor A. Effectiveness of Hemcon dental dressing versus conventional method of haemostasis in 40 patients on oral antiplatelet drugs. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12:330–5. doi: 10.12816/0003147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen EC, Chou TC, Gau CH, Tu HP, Chen YT, Fu E. Releasing growth factors from activated human platelets after chitosan stimulation: A possible bio-material for platelet-rich plasma preparation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:572–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amer MZ, Mourad SI, Salem AS, Abdelfadil E. Correlation between International Normalized Ratio values and sufficiency of two different local hemostatic measures in anticoagulated patients. Eur J Dent. 2014;8:475–80. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.143628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]