Disparities in mental health, school functioning, and substance use for LGBTQ youth are exacerbated when they live in foster care or unstable housing.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth are suggested to be overrepresented in unstable housing and foster care. In the current study, we assess whether LGBTQ youth are overrepresented in unstable housing and foster care and examine disparities in school functioning, substance use, and mental health for LGBTQ youth versus heterosexual youth in unstable housing and foster care.

METHODS:

A total of 895 218 students (10–18 years old) completed the cross-sectional California Healthy Kids Survey from 2013 to 2015. Surveys were administered in 2641 middle and high schools throughout California. Primary outcome measures included school functioning (eg, school climate, absenteeism), substance use, and mental health.

RESULTS:

More youth living in foster care (30.4%) and unstable housing (25.3%) self-identified as LGBTQ than youth in a nationally representative sample (11.2%). Compared with heterosexual youth and youth in stable housing, LGBTQ youth in unstable housing reported poorer school functioning (Bs = −0.10 to 0.40), higher substance use (Bs = 0.26–0.28), and poorer mental health (odds ratios = 0.73–0.80). LGBTQ youth in foster care reported more fights in school (B = 0.16), victimization (B = 0.10), and mental health problems (odds ratios = 0.82–0.73) compared with LGBTQ youth in stable housing and heterosexual youth in foster care.

CONCLUSIONS:

Disparities for LGBTQ youth are exacerbated when they live in foster care or unstable housing. This points to a need for protections for LGBTQ youth in care and care that is affirming of their sexual orientation and gender identity.

What’s Known on This Subject:

It has been suggested that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth are overrepresented in unstable housing and foster care and that the care they receive is not affirming of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

What This Study Adds:

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth were overrepresented in foster care and unstable housing and report worse school functioning, higher substance use, and poorer mental health compared with heterosexual youth in stable housing. Affirmative care is needed.

For youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ), disclosing their sexual identity to family members can mean facing verbal and physical harassment,1–3 sometimes even resulting in out-of-home placement or homelessness.4–6 Because of high rates of rejection and abuse among LGBTQ youth,7,8 it has been suggested that they are overrepresented in unstable housing and the child welfare system.9–14 When placed in an out-of-home setting, LGBTQ youth are more likely to experience victimization and abuse by social work professionals, foster parents, and peers, which has been shown to be related to a lack of permanency15–17 and poorer functional outcomes.18 Existing studies have relied on local or regional samples or on samples of youth living out-of-home. With the current study, we use data from a large statewide school-based survey to assess, first, whether LGBTQ youth are overrepresented in unstable housing (defined according to guidelines from the federal McKinney-Vento Act as living in a friend’s home, hotel or motel, or shelter and other transitional housing19) and foster care (foster home, group care, or waiting placement). Second, we examine disparities in school functioning, substance use, and mental health for LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care compared with heterosexual youth in unstable housing and foster care and LGBTQ youth in stable housing.

A number of legal and social work professional accounts17,20 as well as researchers in qualitative studies have suggested an overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in out-of-home care.15 In a study in Los Angeles County, researchers confirmed that there were 2.3 times more LGBTQ youth in foster care than would be expected based on estimates of LGBTQ youth in national adolescent populations.14,21 Once in out-of-home care, LGBTQ youth are found to experience further mistreatment,14,22 such as verbal and physical violence, and more frequent hospitalization for emotional and physical reasons.4,14 In addition, LGBTQ youth in out-of-home placements have a general lack of formal and informal supportive relationships with adults,23,24 resulting in lower educational attainment, homelessness, and financial instability.18 The mistreatment of LGBTQ youth in their own family or foster family may lead them to leave their home, which is related to an overlapping issue: homelessness.9,10,12,13,25

In addition to research signaling an overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in foster care, African American and American Indian youth are also found to be overrepresented in foster care.26–30 However, researchers have not examined whether LGBTQ youth are more vulnerable when they are in foster care or forms of unstable housing and from these racial and ethnic groups. Recognizing this gap in the literature, we explore whether outcomes differ for African American and American Indian youth (compared with non-Hispanic white youth) by LGBTQ status and living situation.

With the current study, we provide an examination of overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care, and we examine disparities in school functioning, substance use, and mental health for LGBTQ youth versus heterosexual youth in stable housing versus unstable housing and foster care.

Methods

Participants

The data used in this study are from the 2013 to 2015 California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) (N = 910 885). CHKS is conducted in middle and high schools across California and administered by WestEd to track health risks and resilience among youth.31 Both parents and students gave active or passive informed consent (dependent on the school’s requirements), and students’ participation was voluntary and anonymous. As recommended by WestEd, youth whose response validity was questionable were excluded. Exclusion of these youth was based on meeting 2 or more criteria related to inconsistent responses (eg, never using a drug and use in the past 30 days, exaggerated drug use, using a fake drug, and answering dishonestly to all or most of the questions on the survey).32 On the basis of these criteria, data from 1.7% of youth were excluded from the current analyses.

Students from schools that administered the question about living situation and sexual orientation and/or gender identity were included in the analytic sample. The analytic sample comprises 593 241 students (age range 10–18) enrolled in grades 6 to 12, or ungraded, across 1211 schools. Slightly less than one-half of respondents identified as male (49.6%) and 50.4% identified as female. Respondents were asked about their ethnic and racial background; over half (52.0%) of respondents identified as Hispanic. In addition, 24.6% identified as white non-Hispanic, 13.8% as Asian American, 2.7% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 5.8% as African American, 4.7% as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 40.49% as multiracial. See Supplemental Table 4 for characteristics of students by housing situation and LGBTQ status.

Measures

School Functioning

Grades were assessed with the following item: “During the past 12 months, how would you describe the grades you mostly received in school” (1 = mostly A’s, 8 = mostly F’s). Absenteeism was assessed with the following item: “During the past 12 months, about how many times did you skip school or cut classes” (1 = 0 times, 6 = more than once a week). Perceived school safety was assessed with 2 items. An example item is "I feel safe in my school" (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). School climate was assessed with 14 items about school belongingness, teacher-student relationships, and meaningful participation (α = .89). An example item is “I am happy to be at this school” (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Whether youth reported fights in school was assessed with the average of 7 items (α = .78). For example, “During the past 12 months, how many times on school property have you been in a physical fight?” (1 = 0 times, 4 = 4 or more times). Whether youth experienced victimization at school was assessed with the average of 6 items (α = .79). For example, “During the past 12 months, how many times on school property have you been pushed, shoved, slapped, hit, or kicked by someone who wasn’t just kidding around?” (1 = 0 times, 4 = 4 or more times).

Substance Use

Substance use was assessed with the average of 3 items: “During the past 30 days on how many days on school property did you (1) smoke cigarettes, (2) have at least 1 drink of alcohol, (3) smoke marijuana?” (1 = 0 days, 6 = 20–30 days; α = .68); and “During your life, how many times have you been very drunk or sick after drinking alcohol” (1 = 0 times, 6 = 7 or more times).

Mental Health

Whether youth had felt depressed was assessed with the following item: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for 2 weeks or more that you stopped doing some usual activities?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). Whether youth had seriously considered suicide was assessed with the following item: “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Living Situation

Participants were asked about their living situation: “What best describes where you live? A home includes a house, apartment, trailer, or mobile home.” Participants could check 1 of the following categories: (1) A home with 1 or more parents or guardians; (2) other relative’s home; (3) a home with more than 1 family; (4) friend’s home; (5) foster home, group care, or waiting placement; (6) hotel or motel; (7) shelter, car, campground, or other transitional or temporary housing; (8) other living arrangement. Those who chose option 1, 2, or 3 were classified as living in stable housing (n = 548 817); those who chose option 4, 6, 7, or 8 were classified as living in unstable housing (n = 20 231); those who chose option 5 were classified as living in foster care (n = 3344).

Gender and Sexual Identity

Participants were asked about their gender and sexual identity with 1 item. Participants could check 1 or more of the following categories: heterosexual (straight) (n = 443 013); gay or lesbian or bisexual (n = 35 126); transgender (n = 7931); not sure (n = 26 065); or decline to respond (n = 31 651). Categories are not mutually exclusive, and reported sample sizes are limited to students who completed the question on living situation. For the focal analyses, we compared youth who only reported being heterosexual (n = 430 672) to youth who reported being gay or lesbian or bisexual, transgender, or not sure (LGBTQ) or any other composition of answers (n = 62 431).

Race and/or Ethnicity

Students were asked whether they were of “Hispanic or of Latino origin.” With answer options yes or no. Students were also asked, “What is your race?” with the following answer options: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, white, or multiracial (2 or more races). For the current analyses, comparisons were made between African American (1) and non-Hispanic white (0) students and American Indian (1) and non-Hispanic white students (0).

Analysis Strategy

Because CHKS contains nested data (students nested in school), survey-adjusted percentages and means were used to assess the living situation of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Survey-adjusted analyses (svy in Stata [Stata Corp, College Station, TX]) account for the complex (nested) data and adjusts SEs. First, the disproportionality representation index (DRI) was used to document whether LGBTQ youth were overrepresented in foster care. The DRI is calculated by dividing the percentage of LGBTQ youth by the percentage of sexual minority youth in the general population (taken from the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey33). When DRI values are >1.00, this indicates an overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in the CHKS sample; when DRI values are <1.00, this indicates underrepresentation. Second, survey-adjusted (linear and logistic) regression analyses in Stata version 14.0 were conducted to examine whether LGBTQ status, foster care engagement, and unstable housing and interactions between these factors were associated with school functioning, substance use, and mental health. Third, when interaction terms were significant, estimates for LGBTQ youth in foster care and unstable housing were compared with estimates for LGBTQ youth in stable housing, and estimates for LGBTQ youth in foster care and unstable housing were compared with estimates for heterosexual youth in foster care and unstable housing (pwcompare in Stata, Bonferroni adjusted). Last, as sensitivity analyses, we examined whether findings were similar across youth who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB); transgender; or unsure, compared with youth who did not identify as such. In addition, we examined whether there were 3-way interactions between LGBTQ status, living situation, and race and/or ethnicity (African American or American Indian versus non-Hispanic white). In all analyses, we included student age and sex as covariates.

Results

Overrepresentation of LGBTQ Youth in Unstable Housing and Foster Care

Using the estimates of students in different living situations in CHKS, the results revealed an overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in foster care; <1% of our sample is in foster care, but of those youth, 30.4% report an LGBTQ identity (see Table 1). We compared the proportion of LGBTQ youth in foster care in the CHKS sample with data from the 2015 edition of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey that includes a measure of sexual orientation (not gender identity).33 In the national probability-based sample, 11.2% of 12- to 18-year-olds identified as LGB or unsure; comparing this to the percentage of LGBTQ youth in foster care in the current study (30.4%), there is an overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in foster care. This results in a DRI of 2.71. LGBTQ youth are also overrepresented in other forms of unstable housing; 3.53% of our total sample lives in unstable housing, and of those youth, 25.3% report an LGBTQ identity, resulting in a DRI of 2.26. In sum, the proportion of LGBTQ youth in foster care and unstable housing is 2.3 to 2.7 times larger than would be expected from estimates of LGBTQ youth in nationally representative adolescent samples.

TABLE 1.

Survey-Adjusted Percentages of Youth in Housing Situations Overall and by Gender and Sexual Identity

| Overall | Heterosexual | LGBTQ | LGB | Transgender | Unsure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Stable housing | 95.88 (95.76–96.00) | 87.85 (87.62–88.08) | 12.15 (11.92–12.38) | 6.14 (5.99–6.28) | 1.17 (1.13–1.22) | 4.53 (4.43–4.63) |

| Unstable housing | 3.53 (3.44–3.64) | 74.68 (73.89–74.47) | 25.32 (24.53–26.11) | 10.04 (9.58–10.51) | 4.95 (4.57–5.35) | 8.70 (8.25–9.16) |

| Foster care | 0.58 (0.55–0.62) | 69.60 (67.79–71.36) | 30.40 (28.64–32.21) | 13.87 (12.74–15.10) | 5.04 (4.32–5.87) | 6.74 (5.95–7.62) |

CI, confidence interval.

Disparities by Sexual and Gender Identity and Housing

With several survey-adjusted regression analyses, we examined whether LGBTQ youth and youth in unstable housing and foster care compared with heterosexual youth and youth in stable housing differed in their school functioning, substance use, and mental health. Generally, the results revealed that LGBTQ youth report poorer school functioning, more substance use, and poorer mental health compared with heterosexual youth (P < .001). Youth in unstable housing (P < .001) and foster care (P < .001) also reported poorer school functioning, more substance use, and poorer mental health compared with youth in stable housing (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Survey-Adjusted Regression Analyses and Means of School Functioning, Substance Use, Mental Health of Heterosexual and LGBTQ Youth in Stable Housing, Unstable Housing, and Foster Care

| Heterosexual | LGBTQ | Main | Interaction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Housing | Unstable Housing | Foster Care | Stable Housing | Unstable Housing | Foster Care | LGBTQ | Unstable Housing | Foster Care | LGBTQ × Unstable | LGBTQ × Foster Care | |

| Mean (SE) or % | Mean (SE) or % | Mean (SE) or % | Mean (SE) or % | Mean (SE) or % | Mean (SE) or % | B or OR | B or OR | B or OR | B or OR | B or OR | |

| School functioning | |||||||||||

| Grades past 12 mo | 3.11 (0.02) | 3.85 (0.02) | 3.94 (0.05) | 3.43 (0.02) | 4.09 (0.04)a,b | 4.21 (0.08) | 0.37*** | 0.73*** | 0.82*** | −0.10* | −0.00 |

| Absenteeism past 12 mo | 1.84 (0.01) | 2.33 (0.02) | 2.67 (0.05) | 2.11 (0.02) | 2.97 (0.04)a,b | 3.12 (0.07) | 0.28*** | 0.60*** | 0.84*** | 0.40*** | 0.16 |

| Perceived school safety | 3.73 (0.01) | 3.49 (0.01) | 3.53 (0.03) | 3.15 (0.02) | 3.14 (0.02)a,b | 3.20 (0.04) | −0.27*** | −0.26*** | −0.21*** | −0.07** | −0.08 |

| School climate | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.23 (0.01) | −0.19 (0.02) | −0.18 (0.01) | −0.43 (0.01)a,b | −0.32 (0.03) | −0.17*** | −0.23*** | −0.16*** | −0.03* | 0.04 |

| Fights in school | 1.18 (0.00) | 1.34 (0.01) | 1.45 (0.02) | 1.35 (0.01) | 1.76 (0.02)a,b | 1.81 (0.03)a,c | 0.19*** | 0.21*** | 0.30*** | 0.23*** | 0.16*** |

| Victimization | 1.43 (0.00) | 1.54 (0.01) | 1.63 (0.02) | 1.74 (0.01) | 2.00 (0.02)a,b | 2.07 (0.03)a,c | 0.31*** | 0.14*** | 0.22*** | 0.13*** | 0.10* |

| Substance use | |||||||||||

| Substance use during past 30 d | 1.35 (0.01) | 1.61 (0.01) | 1.84 (0.03) | 1.59 (0.01) | 2.12 (0.03)a,b | 2.22 (0.05) | 0.26*** | 0.33*** | 0.50*** | 0.26*** | 0.11 |

| Drunk or sick after drinking alcohol | 1.58 (0.01) | 1.89 (0.02) | 2.25 (0.06) | 2.51 (0.03) | 2.46 (0.03)a,b | 2.74 (0.07) | 0.32*** | 0.40*** | 0.70*** | 0.28*** | 0.16 |

| Mental health | |||||||||||

| Depressed for 2 wk or more during past 12 mo | 29.23 | 35.56 | 37.31 | 53.23 | 52.34b | 57.75c | 2.50*** | 1.32*** | 1.40*** | 0.73*** | 0.82* |

| Seriously considered suicide past 12 mo | 15.13 | 20.92 | 25.04 | 39.75 | 43.30a,b | 48.55a,c | 3.39*** | 1.43*** | 1.69*** | 0.80*** | 0.73** |

Controlling for student age and sex. Stable housing is the reference category. Sample sizes ranged from 476 922 (depressive symptoms) to 482 779 (school climate). OR, odds ratio.

Significantly different from LGBTQ youth in stable housing (P < .05).

Significantly different from heterosexual youth in unstable housing (P < .05).

Significantly different from heterosexual youth in foster care (P < .05).

P < .05; ** P < .005; *** P < .001.

To examine the interaction between LGBTQ status (LGBTQ versus heterosexual) and living situation (foster care versus stable housing; unstable housing versus stable housing) in terms of school functioning, substance use, and mental health, we added 2 interaction terms to the model: LGBTQ × unstable housing and LGBTQ × foster care. The findings revealed significant interaction effects, indicating disparities for LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care for several outcomes.

Compared with heterosexual youth in unstable housing and LGBTQ youth in stable housing, LGBTQ youth in unstable housing reported lower grades (P = .020), higher rates of absenteeism (P < .001), school safety (P = .001), lower school climate (P = .049), more fights in school (P < .001), and more victimization (P < .001). They were also more likely to have been depressed (not different from LGBTQ youth in stable housing) or suicidal in the past year, to have been drunk or sick from alcohol (P < .001), and they reported higher levels of substance use (P < .001).

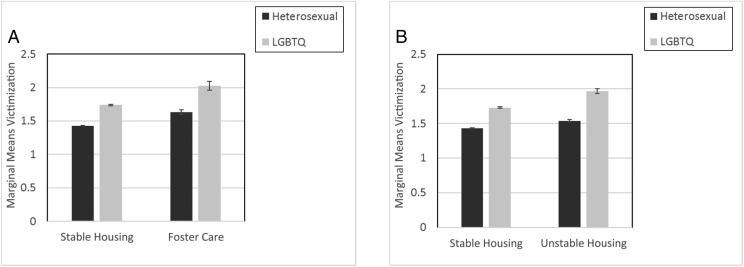

Compared with heterosexual youth in foster care and LGBTQ youth in stable housing, LGBTQ youth in foster care reported more fights in school (P < .001) and more victimization (P = .009). They were also more likely to have been depressed (not different from LGBTQ youth in stable housing) or suicidal in the past year. See Table 2 and Fig 1 for an example.

FIGURE 1.

A, Interaction foster care × LGBTQ. B, Interaction unstable housing × LGBTQ for victimization.

We also tested main effects and interactions with LGB, unsure, and transgender status (Supplemental Table 5). Findings from main effects were largely similar to the analyses, including LGBTQ status. However, interaction effects became nonsignificant for LGB youth in foster care (except for suicidality) and unsure youth in unstable housing (except for grades, school climate, fights in school, and mental health) and foster care (except for mental health). Disparities were most robust for transgender youth in unstable housing and transgender youth in foster care.

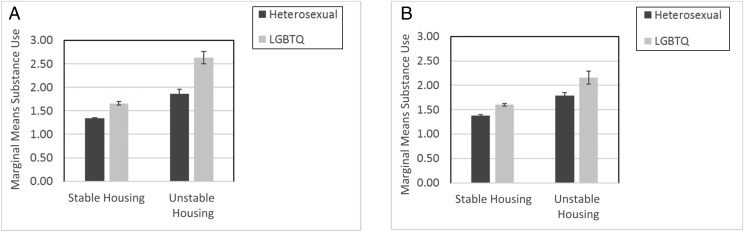

To examine whether associations between LGBTQ status and living situation were different for African American and American Indian youth, we added the following set of interaction terms to the models: LGBTQ × unstable housing × African American and LGBTQ × foster care × African American and separately LGBTQ × unstable housing × American Indian and LGBTQ × foster care × American Indian (Table 3). For LGBTQ African American students in unstable housing, there are significant interactions for school safety (B = −0.21, P = .026), school climate (B = −0.20, P = .001), fighting at school (B = 0.28, P < .001), victimization (B = 0.26, P = .001), substance use (B = 0.29, P = .009), and having been drunk or sick from alcohol (B = 0.63, P < .001). Overall, these results revealed a general pattern of LGBTQ African American students living in unstable housing reporting poorer outcomes compared with LGBTQ non-Hispanic white students living in unstable housing. See Fig 2 for an example. For LGBTQ African American students in foster care, there are significant interactions for school absenteeism (B = 0.66, P = .038), fighting at school (B = 0.31, P = .017), victimization (B = 0.35, P = .028), substance use (B = 0.77, P = .001), and having been drunk or sick from alcohol (B = 1.13, P = .002). Similar to patterns for youth living in unstable housing, the results revealed a general pattern of LGBTQ African American students living in foster care reporting poorer outcomes compared with LGBTQ non-Hispanic white students living in foster care. Interactions between LGBTQ status and living situation for American Indian students were not significant (P > .05).

TABLE 3.

Survey-Adjusted Means, SE, and Percentages for African American and American Indian Heterosexual and LGBTQ Youth in Unstable Housing, Stable Housing, and Foster Care

| Heterosexual | LGBTQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Housing | Unstable Housing | Foster Care | Stable Housing | Unstable Housing | Foster Care | |

| African American, n | 18 810 | 834 | 210 | 3353 | 540 | 121 |

| School functioning, mean (SE) | ||||||

| Grades past 12 mo | 3.54 (0.03) | 4.12 (0.09) | 4.43 (0.15) | 3.77 (0.04) | 4.62 (0.12) | 4.84 (0.15) |

| Absenteeism past 12 mo | 1.89 (0.02) | 2.94 (0.07) | 2.95 (0.14) | 2.29 (0.03) | 3.83 (0.09) | 3.77 (0.18) |

| Perceived school safety | 3.58 (0.02) | 3.27 (0.04) | 3.52 (0.08) | 3.33 (0.02) | 2.76 (0.06) | 3.00 (0.11) |

| School climate (standardized) | −0.06 (0.01) | −0.36 (0.03) | −0.19 (0.05) | −0.19 (0.01) | −0.65 (0.04) | −0.31 (0.08) |

| Fights in school | 1.23 (0.00) | 1.55 (0.03) | 1.46 (0.05) | 1.48 (0.02) | 2.19 (0.05) | 1.97 (0.08) |

| Victimization | 1.46 (0.01) | 1.64 (0.03) | 1.64 (0.06) | 1.76 (0.02) | 2.25 (0.05) | 2.22 (0.08) |

| Substance use, mean (SE) | ||||||

| Substance use during past 30 d | 1.35 (0.01) | 1.85 (0.05) | 1.73 (0.08) | 1.68 (0.02) | 2.56 (0.07) | 2.52 (0.13) |

| Drunk or sick after drinking alcohol | 1.41 (0.01) | 2.23 (0.07) | 1.99 (0.12) | 1.81 (0.03) | 3.12 (0.09) | 3.06 (0.19) |

| Mental health, % | ||||||

| Depressed for 2 wk or more during past 12 mo | 23.85 | 29.65 | 35.18 | 44.28 | 46.71 | 55.10 |

| Seriously considered suicide past 12 mo | 12.58 | 19.75 | 22.96 | 34.33 | 41.25 | 50.00 |

| American Indian, n | 14 993 | 788 | 204 | 2506 | 266 | 60 |

| School functioning, mean (SE) | ||||||

| Grades past 12 mo | 3.60 (0.03) | 3.62 (0.08) | 3.45 (0.15) | 3.67 (0.04) | 3.76 (0.15) | 3.58 (0.29) |

| Absenteeism past 12 mo | 2.01 (0.02) | 2.55 (0.06) | 2.45 (0.11) | 2.24 (0.04) | 3.07 (0.13) | 2.94 (0.24) |

| Perceived school safety | 3.63 (0.01) | 3.53 (0.03) | 3.47 (0.07) | 3.37 (0.02) | 3.11 (0.07) | 3.18 (0.14) |

| School climate (standardized) | −0.12 (0.01) | −0.23 (0.03) | −0.25 (0.05) | −0.27 (0.02) | −0.44 (0.05) | −0.42 (0.09) |

| Fights in school | 1.23 (0.01) | 1.33 (0.02) | 1.41 (0.05) | 1.50 (0.02) | 1.76 (0.05) | 1.64 (0.10) |

| Victimization | 1.41 (0.01) | 1.47 (0.02) | 1.54 (0.05) | 1.80 (0.02) | 1.94 (0.06) | 1.90 (0.11) |

| Substance use, mean (SE) | ||||||

| Substance use during past 30 d | 1.44 (0.01) | 1.61 (0.04) | 1.82 (0.09) | 1.73 (0.03) | 2.08 (0.09) | 1.88 (0.16) |

| Drunk or sick after drinking alcohol | 1.68 (0.02) | 1.94 (0.06) | 2.16 (0.12) | 2.04 (0.04) | 2.40 (0.11) | 2.23 (0.23) |

| Mental health, % | ||||||

| Depressed for 2 wk or more during past 12 mo | 29.51 | 30.57 | 30.61 | 51.58 | 48.31 | 56.60 |

| Seriously considered suicide past 12 mo | 15.15 | 17.49 | 29.15 | 40.75 | 37.99 | 46.15 |

FIGURE 2.

A, Interaction LGBTQ × unstable housing for African American students for substance use. B, Interaction LGBTQ × unstable housing for non-Hispanic white students for substance use.

Discussion

The current study shows that LGBTQ youth are overrepresented in unstable housing and foster care. Our findings also revealed that LGBTQ youth in unstable housing have poorer school functioning outcomes (eg, absenteeism, safety, victimization), higher substance use, and poorer mental health (depression, suicidality) compared with LGBTQ in stable housing and heterosexual youth in unstable housing. For youth in foster care, disparities for LGBTQ youth were less robust; LGBTQ youth in foster care reported more fights in school and victimization and more mental health problems (although depression did not differ from LGBTQ youth in stable housing). In addition, exploratory analyses revealed the disadvantaged position for LGBTQ African American youth in unstable housing in terms of substance use, mental health problems, and school functioning. The findings revealed similar patterns of disparities for American Indian youth, but these differences did not reach significance, likely because of small sample sizes.

We sought to understand the similar and distinct ways multiple forms of nonpermanency experienced by youth were associated with various outcomes. The current findings revealed a larger overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in foster care than was previously found.14 Considering the current sample is geographically more comprehensive and diverse than the earlier study in Los Angeles County,14 we conclude that earlier estimations of overrepresentation may reflect underestimates at the state level. In the context of unstable housing, our estimates of LGBTQ youth in California appear consistent with previous estimates of overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth who are unstably housed, although this area of research is less developed. In previous studies, researchers assessing sexual orientation and gender identity among unstably housed youth (typically studied under the framework of youth experiencing homelessness) have estimated that LGBTQ youth make up anywhere from 20% to 45% of homeless youth.12,34,35 As such, it is unclear how this study compares to previous assessments of disproportionality of LGBTQ youth in unstable housing. However, because almost all previous reports of sexual orientation and gender identity demographics among unstably housed youth indicate high rates of LGBTQ youth in this subpopulation, it is clear that the current study is consistent with others in its claim of disproportionality.

Our findings suggest that LGBTQ youth living in foster care or unstable housing are similar in some ways; both groups showed disparities in victimization and mental health, whereas only unstably housed LGBTQ youth showed disparities in school functioning and substance use. One might, therefore, conclude that LGBTQ youth in foster care are in some way protected from negative school functioning and substance use outcomes, at least during adolescence.

Implications

California is 1 of only 13 states that has laws and policies in place to protect foster youth from harassment and discrimination based on both sexual orientation and gender identity.11,36 However, the current findings revealed that LGBTQ foster care youth in California are not faring as well as their non-LGBTQ or non–foster care counterparts, indicating potential areas for future research and intervention. Not only does previous research indicate that LGBTQ youth experience rejection in foster care and other child welfare settings, it also suggests that the child welfare system is not prepared to provide safe and affirming care.4,15–17 With this study, we highlight the importance of encouraging further cross-system collaboration within county and state departments to address the unique needs of sexual- and gender-minority youth.37

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

There are several important limitations to note. The current data are cross-sectional and not representative of all adolescents in California. Therefore, we cannot conclude any causal mechanisms and, despite the large sample size, we cannot generalize our findings to youth in California that did not participate. Because youth in different forms of unstable housing are less likely to be enrolled in school or regularly attend school, and the current study used a school-based survey, the CHKS sample may present an underrepresentation of marginally housed youth in California. Moreover, we cannot ascertain whether disparities are even more severe in states without protections from harassment and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Further, as the CHKS only contains self-report measures, some youth may underreport undesirable behaviors such as truancy and experiences of violence. In addition, because of a lack of information about family relationships and stability in the home, we cannot conclude that living with parents is more stable for LGBTQ youth than living in foster care. However, empirical work does suggest that because of a higher number of placements, foster care might be particularly unstable for LGBTQ youth.14 Qualitative work could home in on the environment from which youth are removed and why LGBTQ youth are moved from placement to placement more often than heterosexual youth. Focusing on young people’s experiences should offer more detailed information about families, foster parents, siblings, and the role of school.

Conclusions

Using a statewide youth sample, we document overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care and disproportionate risks related to schooling, substance use, and mental health. LGBTQ youth, in general, showed poorer outcomes, which was exacerbated when they lived in unstable housing or foster care. The findings of this study point to the need for care that is affirming and respectful of youth’s sexual orientation and gender identity.

Glossary

- CHKS

California Healthy Kids Survey

- DRI

disproportionality representation index

- LGB

lesbian, gay, or bisexual

- LGBTQ

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning

Footnotes

Drs Russell, Wilson, and Baams conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Baams conducted the initial analyses; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by grant P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors acknowledge generous support from the Communities for Just Schools Fund and support for Dr Russell from the Priscilla Pond Flawn Endowment at the University of Texas at Austin. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(3):361–371; discussion 372–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz-Wise SL, Rosario M, Tsappis M. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth and family acceptance. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):1011–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):985–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winter C. Health equity series: responding to LGBT health disparities. 2012. Available at: https://mffh.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/LGBTHealthEquityReport.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2017

- 5.Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berberet HM. Putting the pieces together for queer youth: a model of integrated assessment of need and program planning. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2):361–384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1481–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baams L. Disparities for LGBTQ and gender nonconforming adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman L, Hamilton D A count of homeless youth in New York City. 2008. Available at: http://www.racismreview.com/downloads/HomelessYouth.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2019

- 10.Gangamma R, Slesnick N, Toviessi P, Serovich J. Comparison of HIV risks among gay, lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual homeless youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37(4):456–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Human Rights Campaign LGBTQ youth in the foster care system. 2015. Available at: http://hrc-assets.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com//files/assets/resources/HRC-YouthFosterCare-IssueBrief-FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2017

- 12.Van Leeuwen JM, Boyle S, Salomonsen-Sautel S, et al. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: an eight-city public health perspective. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2):151–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitbeck LB, Johnson KD, Hoyt DR, Cauce AM. Mental disorder and comorbidity among runaway and homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson BDM, Kastanis AA. Sexual and gender minority disproportionality and disparities in child welfare: a population-based study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;58:11–17 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallon GP, Aledort N, Ferrera M. There’s no place like home: achieving safety, permanency, and well-being for lesbian and gay adolescents in out-of-home care settings. Child Welfare. 2002;81(2):407–439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yarbrough J. Information packet: LGBTQ youth permanency. 2012. Available at: www.hunter.cuny.edu/socwork/nrcfcpp/info_services/download/LGBTQ Youth Permanency_JesseYarbrough.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2017

- 17.Wilber S, Reyes C, Marksamer J. The model standards project: creating inclusive systems for LGBT youth in out-of-home care. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2):133–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shpiegel S, Simmel C. Functional outcomes among sexual minority youth emancipating from the child welfare system. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;61:101–108 [Google Scholar]

- 19.The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, Subtitle VII-B Reauthorized by Title IX. 42 US Code §§11431–11435

- 20.Irvine A, Canfield A. The overrepresentation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming and transgender youth within the child welfare to juvenile justice crossover population. Am Univ J Gend Soc Policy Law. 2016;24(2):243–261 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gates GJ, Newport F. Special Report: 3.4% of US Adults Identify as LGBT. Washington, DC: Gallup; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell RC, Panzarello A, Grynkiewicz A, Galupo MP. Sexual minority and heterosexual former foster youth: a comparison of abuse experiences and trauma-related beliefs. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2015;27(1):1–16 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freundlich M, Avery RJ. Gay and lesbian youth in foster care. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2004;17(4):39–57 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolan TC. Outcomes for a transitional living program serving LGBTQ youth in New York City. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2):385–406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray N, Berger C Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth: an epidemic of homelessness. Available at: http://www.thetaskforce.org/lgbt-youth-an-epidemic-of-homelessness/. Accessed January 12, 2019

- 26.Garland AF, Landsverk JA, Lau AS. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among children in foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2003;25(5–6):491–507 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn NE, Hansen ME. Measuring racial disparities in foster care placement: a case study of Texas. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;76:213–226 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B, King B, Johnson-Motoyama M. Racial and ethnic disparities: a population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(1):33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bass S, Shields MK, Behrman RE. Children, families, and foster care: analysis and recommendations. Future Child. 2004;14(1):4–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Needell B, Brookhart MA, Lee S. Black children and foster care placement in California. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2003;25(5–6):393–408 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin G, Hanson T, Skager R, Polik J, Clingman M Fourteenth biennial statewide survey of alcohol and drug use among California students in grades 7, 9, and 11. Highlights 2011–2013. Available at: http://chks.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/14thBiennialReport.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017

- 32.Austin G, Bates S, Duerr M Guidebook to the California Healthy Kids Survey. Part II: survey content – core module. Available at: http://surveydata.wested.org/resources/chks_guidebook_2_coremodules.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017

- 33.Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9-12 - United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(9):1–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Tyler KA, Johnson KD. Mental disorder, subsistence strategies, and victimization among gay, lesbian, and bisexual homeless and runaway adolescents. J Sex Res. 2004;41(4):329–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durso LE, Gates GJ Serving our youth: findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexuals and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. 2012. Available at: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/80x75033. Accessed July 26, 2017

- 36.NCLR LGBTQ youth in the California foster care system: a question and answer guide. 2006. Available at: www.nclrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/LGBTQ_Youth_California_Foster_System.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2017

- 37.Cooper KC, Wilson BDM, Choi SK. Los Angeles County LGBTQ Youth Preparedness. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles School of Law; 2017 [Google Scholar]