Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) pseudoparticles (HCVpp) are generated by cotransfection of HCV envelope (E1 and E2) genes along with a retroviral packaging/reporter construct into HEK293T cells. Enveloped particles bearing HCV E1E2 proteins on their surface are released through a retroviral budding process into the supernatant. Viral E1E2 glycoproteins facilitate a single round of receptor-mediated entry of HCVpp into hepatoma cells, which can be quantified by reporter gene expression. These HCVpp have been employed to study mechanisms of HCV entry into hepatoma cells, as well as HCV neutralization by immune sera or HCV-specific monoclonal antibodies.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Flaviviridae, HCV pseudoparticles, Neutralizing antibodies, Neutralizing breadth

1. Introduction

The development of HCVpp [1, 2] has advanced studies of HCV entry and neutralization by antibodies for more than a decade. HCVpp were first used to identify HCV cell surface receptors required for viral entry [3–6]. More recently, studies using HCVpp have also advanced understanding of HCV neutralization by antibodies [7–13], establishing that neutralizing antibodies can drive evolution in vivo of HCV E1E2, leading to neutralization escape [11, 14]. These particles have been produced with a variety of E1E2 variants from multiple isolates and genotypes [15]. Diverse HCVpp panels have been used to define neutralizing breadth of antibodies and to show that development of broadly neutralizing antibodies is associated with spontaneous clearance of HCV infection [10, 11], and reduced liver fibrosis in chronic infection [16].

Key issues to allow comparison of HCVpp neutralization among different laboratories are quality of pseudoparticles that are generated from clinical isolates and use of appropriate controls in neutralization assays. The following protocol addresses these issues.

2. Materials

Recommended vendors are listed in parentheses. Unless otherwise specified, products of equal or better quality than the recommended ones can be used whenever necessary.

HEK293T cells (ATCC).

Huh7 (APATH, L.L.C.) or Hep3B2.1–7 (“Hep3B”, ATCC) hepatoma cells.

HEK293T/Huh7 growth medium: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco), supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1× nonessential amino acids (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco).

HEP3B growth medium: Modified Eagle medium (MEM, Gibco), supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1× nonessential amino acids (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco).

Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen).

6-well or 10 cm Primaria-coated tissue culture dishes (Corning).

96-well white flat bottom tissue culture plates (Corning).

0.45 micron filters (Millipore).

37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator.

5× Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega).

Luciferase Assay System reagent (Promega).

Luminometer (Berthold or BMG Labtech).

HCV E1E2 in pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.2 expression plasmids (Invitrogen).

Murine Leukemia Virus (MLV) Envelope expression plasmid or Vesicular Stomatitis Virus-G (VSV-G) Envelope expression plasmid (NIH AIDS Reagent Program).

2.1. For HIV Gag-Packaged HCVpp Production

Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

pNL4.3.Luc.R-E-plasmid (NIH AIDS Reagent Program).

pAdvantage plasmid (Promega).

2.2. For MLV Gag-Packaged HCVpp Production

Polyethylenimine (PEI), MW 25,000 (Polyscience).

phCMV MLV Gag/Pol packaging construct (phCMV-5349).

pTG126 Luciferase encoding reporter.

3. Methods

3.1. Generation of HCVpp by Transfection

Two different transfection protocols in Subheading 3.1 have been optimized for generation of either HIV Gag-packaged or MLV Gag-packaged pseudoparticles.

3.1.1. Generation of HIV Gag-Packaged Pseudoparticles

Day 1: For each HCVpp to be produced, seed 1 × 106 HEK293T cells into each well of a 6-well tissue culture plate in 3 mL of HEK293T growth medium and incubate overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Culture size can be scaled up as needed.

Day 2: Check the density of cells seeded the day before. They should be well spaced over the entire dish and at a confluency of around 70%.

For each HCVpp to be produced, dilute 2 μg pNL4.3.Luc.R-E- plasmid, 1 μg E1E2 expression plasmid, and 0.5 μg pAdvantage plasmid in 250 μL Opti-MEM medium.

For each HCVpp to be produced, dilute 12 μL Lipofectamine 2000 in 250 μL Opti-MEM.

- Generation of control pseudoparticles:

- To generate mock pseudoparticles without E1E2 (a control for nonspecific entry) repeat steps 3 and 4, but do not add any E1E2 expression plasmid.

- To generate MLV or VSV-G-enveloped pseudoparticles (a control for nonspecific neutralization), repeat steps 3 and 4, but replace HCV E1E2 with MLV or VSV-Genvelope expression plasmid.

Mix diluted plasmids with diluted Lipofectamine and incubate for 20–30 min at room temperature, then add drop-wise to HEK293T cells without removing growth medium.

Incubate overnight at 37 °C in a humidified incubator, then remove medium and replace with 2 mL of fresh HEK293T growth medium.

Incubate at 37 °C in a humidified incubator for 48 h. Harvest media and store at 4 °C. Replace media in wells with fresh growth medium and incubate at 37 °C in a humidified incubator for 24 more hours.

Day 5: Pool 48 h and 72 h supernatants from each well and pass it through a 0.45 μM filter. This supernatant contains the pseudoparticles and can be used either immediately, stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 2 weeks, or frozen at −80 °C indefinitely (see Note 1).

3.1.2. Generation of MLV Gag-Packaged Pseudoparticles

Day 1: For each HCVpp to be produced, seed 1.2 × 106 HEK293T cells into a 10 cm diameter Primaria coated dish (Corning) in 10 mL of HEK293T growth medium and incubate overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Day 2: Check the density of cells seeded the day before. They should be well spaced over the entire dish and at a confluency of around 50%.

For each HCVpp to be produced, mix 2 μg of phCMV-5349 (MLV Gag/Pol packaging construct), 2 μg of pTG126 Luciferase reporter construct and 2 μg of E1E2 expression plasmid together in a 1.7 mL Eppendorf tube, topped up to 300 μL with Opti-MEM.

In a separate tube mix 276 μL of Opti-MEM with 24 μL cationic polymer transfection reagent (Polyethylenimine, PEI; Polyscience) (see Note 2).

Add the 300 μL PEI–Opti-MEM mix to the Eppendorf containing the plasmid mix to give a total of 600 μL.

- Generation of control pseudoparticles:

- To generate mock pseudoparticles (control for nonspecific entry), repeat steps 3–5, but do not add any E1E2 construct.

- To generate MLV or VSV-G-enveloped pseudoparticles (control for nonspecific neutralization), repeat steps3–5, but replace HCV E1E2 expression plasmid with MLV or VSV-G-envelope expression plasmid.

Incubate at RT for 1 h.

During this hour, remove the complete media with a serological pipette, taking care not to disrupt the cell layer. Add 7 mL of Opti-MEM by tilting the dish and pipetting into the bottom so as not to disturb the cells.

Add all 600 μL of the plasmid–PEI mix to the cells, dropwise across the top to ensure even spread.

Incubate for 6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Remove the Opti-MEM and replace with 10 mL of complete medium.

Incubate at 37 °C in a humidified incubator for 72 h.

Day 5: Remove the supernatant from the dish and pass it through a 0.45 μM filter. This supernatant contains the pseudoparticles. This can be used either immediately or stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 2 weeks.

3.2. Single Round Infection of Hepatoma Cells

Day 1: Seed 1.5 × 104 Huh7 cells or 8×103 Hep3B cells per well into a 96-well white flat bottom tissue culture plate (Corning) in 100 μL of growth medium and incubate overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2 (see Note 3).

Day 2: Serially dilute HCVpp and mock pseudoparticles twofold into Huh7 or Hep3B growth medium, depending on the target cells to be infected.

Remove growth medium from cells and replace it with 100 μL of diluted HCVpp or mock pseudoparticles in duplicate or triplicate.

Incubate for 4–6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Replace medium with a phenol-free growth medium and incubate cells at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h.

Day 5: Discard the medium from each well and add 50 μL of 1× cell Lysis buffer (Promega) to each well.

Incubate at RT for 15 min.

Detect luminescence by adding 50 μL of luciferase reagent (Promega) per well and quantitate relative light units (RLU) for 1–5 s after a 0.2 s delay using a luminometer.

Quality control of HCVpp: HCVpp with functional E1E2 generally produce RLU values at least 10× greater than mock pseudoparticles, but some HCVpp produced using clinical isolate E1E2 may have lower infectivity. Neutralization results obtained using these low-infectivity HCVpp may be unreliable and should be interpreted with caution (see Notes 4 and 5).

3.3. Neutralization Assay

Day 1: Seed 1.5 × 104 Huh7 cells or 8 × 103 Hep3B cells per well per into a 96-well white flat bottom tissue culture plate (Corning) in 100 μL of growth medium and incubate overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Day 2: If plasma or serum samples are to be tested for neutralizing activity, heat inactivate complement by incubating plasma/serum at 56 °C for 30 min. If white precipitate forms after heat inactivation, samples can be clarified by centrifugation at 1200 × g for 5 min.

Based on result of prior HCVpp infection, dilute HCVpp into HEK293T growth medium to a concentration that will result in infection in the linear range of the infectivity assay. Generally, all but the most infectious HCVpp supernatants can be used undiluted.

Dilute MLV-enveloped or VSV-G-enveloped pseudoparticles to similar level of infectivity to HCVpp to use as a control for nonspecific neutralization.

Neutralization assays are performed in duplicate or triplicate. Each well has a total volume of 100 μL, made up of 90 μL of pseudoparticle and 10 μL of mAb or plasma/serum. Once the highest concentration and dilution series has been calculated, dilute the mAb or plasma/serum accordingly into PBS or complete growth media. MAbs are generally tested at a maximum concentration of 50 μg/mL, and serum is generally tested at a minimum dilution of 1:50.

Dilute an isotype control mAb or nonspecific polyclonal human IgG as a noninhibiting control for neutralizing mAbs. Dilute HCV-negative plasma/serum as a noninhibiting control for neutralization by plasma/serum.

Mix diluted antibody and pseudoparticles and incubate for 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

After 1 h, remove the media from the 96-well white plate seeded with Huh7 or Hep3B cells on Day 1, and add 100 μL of the pseudoparticle/antibody mixture per well, in duplicate or triplicate.

Incubate for 4–6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Replace media with phenol-free growth media and incubatecells at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h.

Day 5: Discard the media from each well and add 50 μL of 1× Cell Lysis Buffer (Promega) to each well.

Incubate at RT for 15 min.

Detect luminescence by adding 50 μL of luciferase reagent (Promega) per well and quantitating relative light units (RLU) for 1–5 s after a 0.2 s delay using a luminometer.

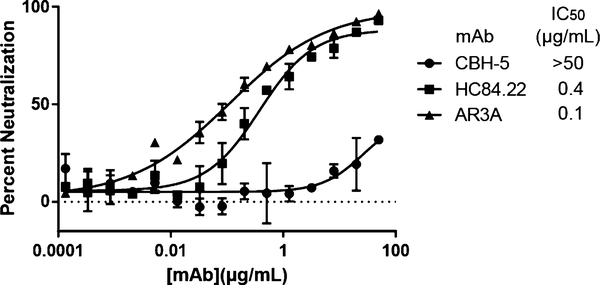

Neutralization at each mAb concentration, serum dilution, or plasma dilution can be calculated using HCVpp infectivity in the presence of test mAb, test serum, or test plasma (RLUtest) relative to infectivity of HCVpp alone (RLUcontrol). Neutralization values can be expressed as percent neutralization [Percent neutralization = (1 – RLUtest/RLUcontrol) × 100]. Fifty-percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) of an inhibitor can be calculated from measurements of percent neutralization by serial dilutions of antibody (see Note 6).

- Quality control of neutralization results:

- Neutralization of MLV-pp or VSV-G-pp should be measured as a control for nonspecific neutralization or enhancement of infection. Neutralization by a test sample should only be considered HCV-specific if neutralization of HCVpp exceeds neutralization of MLV-pp or VSV-G-pp.

- Percent neutralization of HCVpp by a nonspecific control antibody (isotype control mAb or pooled human IgG), HCV negative serum pooled from multiple donors, or HCV negative plasma pooled from multiple donors, as appropriate, should also be measured as a control for nonspecific neutralization or enhancement of HCVpp infection. Optionally, RLU values in the presence of nonspecific control antibody, pooled HCV negative serum, or pooled HCV negative plasma can be used as RLUcontrol in the equation [Percent neutralization = (1 – RLUtest/RLUcontrol) × 100] to adjust percent neutralization of test samples for nonspecific neutralization or enhancement (see Notes 7 and 8).

Fig. 1.

Neutralization of H77 HCVpp by serial dilutions of three reference mAbs. Error bars indicate standard deviations between replicates. From Wasilewski et al. [17]

Table 1.

Percent neutralization of strain H77 HCVpp by reference mAbs, measured at a single concentration of mAb (10 μg/mL). Values are the average of replicate wells. From Bailey et al. [13]

| mAb (10 μg/mL) | H77 HCVpp % Neutralization |

|---|---|

| HC84.26 | 99.7 |

| HC33.4 | 99.6 |

| HC33.8 | 95.7 |

| AR4A | 95.4 |

| AR5A | 91.4 |

| AR3C | 86.9 |

| AR2A | 82.8 |

| HC84.22 | 82.6 |

| AR3A | 76.9 |

| HC-1 | 67.3 |

| AR3D | 67.1 |

| AR4B | 65.7 |

| AR3B | 62.8 |

| CBH-7 | 55.2 |

| AR1A | 36.2 |

| CBH-2 | 35.4 |

| CBH-5 | 33 |

| CBH-4B | 11.3 |

3.4. Measurement of Neutralizing Breadth

Neutralization of an HCVpp is generally considered positive if it is neutralized >50% by 50 μg/mL or less of a mAb or a 1:50 dilution of plasma or serum, with appropriate controls for nonspecific neutralization. Cross-neutralization is generally defined as neutralization of at least one heterologous HCV isolate. Broad neutralization is generally defined as neutralization of the majority of isolates in a diverse panel of HCVpp (see Note 9). Neutralization sensitivity of distinct HCVpp isolates varies widely both within and across HCV genotypes [13, 15], and further study is needed to better define the relationship between neutralizing breadth measured using diverse isolates from a single HCV genotype and neutralizing breadth measured using isolates from multiple genotypes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Stuart Ray for useful discussions. This work was funded by NIH grants R01AI127469, R01AI079031, R01AI106005, U19AI123861, and U19AI088791, Medical Research Council (MRC) grant G0801169 and EU Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) grant “HepaMab” 305600.

Footnotes

HCVpp infectivity decreases by two- to fivefold with each free-ze–thaw cycle.

In MLV-Gag pseudoparticle transfection protocol, add PEI to Opti-MEM, not the other way around.

A confluent T175 flask has ~1 × 107 Hep3B cells, enough to seed ~10–12 96-well plates.

Infectivity can vary significantly between different preparations (transfections) of the same HCVpp, and some E1E2 variants are more likely to produce functional HCVpp when packaged with MLV-Gag rather than HIV-Gag, or vice versa. Some E1E2 variants also require nonstandard ratios of E1E2 plasmid and packaging construct to produce functional pseudoparticles [19].

Inadequate infectivity of HCVpp can sometimes be improved through codon optimization of E1E2 genes. Infectivity may also be improved by switching from HIV Gag-packaged pseudoparticles to MLV Gag-packaged pseudoparticles, or vice versa.

Percent neutralization of the same HCVpp variant by the same antibody at the same concentration can vary by about 1.5-fold between independent experiments (an independent experiment is defined by a different HCVpp transfection and different neutralization assay). Therefore, small differences in neutralization resistance between HCVpp should be confirmed with repeated independent experiments.

Nonspecific enhancement or inhibition of HCVpp by sera may be corrected through the use of protein A purified serum IgG in neutralization experiments.

Heparin can inhibit HCV infection, so plasma isolated with heparin used as an anticoagulant should be avoided or used with appropriate controls.

References

- 1.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL (2003) Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1- E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med 197:633–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M, Logvinoff C,Cheng-Mayer C, Rice CM et al. (2003) Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:7271–7276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, Goujon C,Dubuisson J, Pascale S et al. (2003) Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem 278:41624–41630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cormier EG, Tsamis F, Kajumo F, Durso RJ,Gardner JP, Dragic T (2004) CD81 is an entry coreceptor for hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:7270–7274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKeating JA, Zhang LQ, Logvinoff C, Flint M, Zhang J, Yu J et al. (2004) Diverse hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate viral infection in a CD81-dependent manner. J Virol 78:8496–8505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Randall G, Higginbottom A, Monk P, Rice CM, McKeating JA (2004) CD81 is required for hepatitis C virus glycoprotein-mediated viral infection. J Virol 78:1448–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giang E, Dorner M, Prentoe JC, Dreux M,Evans MJ, Bukh J et al. (2012) Human broadly neutralizing antibodies to the envelope glycoprotein complex of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:6205–6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law M, Maruyama T, Lewis J, Giang E, Tarr AW, Stamataki Z et al. (2008) Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat Med 14:25–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin TJ, Broering TJ, Leav BA, Blair BM,Rowley KJ, Boucher EN et al. (2012) Human monoclonal antibody HCV1 effectively prevents and treats HCV infection in chimpanzees. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osburn WO, Snider AE, Wells BL, Latanich R, Bailey JR, Thomas DL et al. (2014) Clearance of hepatitis C infection is associated with the early appearance of broad neutralizing antibody responses. Hepatology 59:2140–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Blaser E, Schurmann P, Bartosch B, Cosset FL et al. (2007) Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:6025–6030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keck ZY, Xia J, Wang Y, Wang W, Krey T, Prentoe J et al. (2012) Human monoclonal antibodies to a novel cluster of conformational epitopes on HCV e2 with resistance to neutralization escape in a genotype 2a isolate. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey JR, Wasilewski LN, Snider AE, El-Diwany R, Osburn WO, Keck Z et al. (2015) Naturally selected hepatitis C virus polymorphisms confer broad neutralizing antibody resistance. J Clin Invest 125:437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowd KA, Netski DM, Wang XH, Cox AL, Ray SC (2009) Selection pressure from neutralizing antibodies drives sequence evolution during acute infection with hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology 136:2377–2386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbanowicz RA, McClure CP, Brown RJ, Tsoleridis T, Persson MA, Krey T et al. (2016) A diverse panel of hepatitis C virus glycoproteins for use in vaccine research reveals extremes of monoclonal antibody neutralization resistance. J Virol 90:3288–3301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swann RE, Cowton VM, Robinson MW, Cole SJ, Barclay ST, Mills PR et al. (2016) Broad anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody responses are associated with improved clinical disease parameters in chronic HCV infection. J Virol 90:4530–4543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasilewski L, Ray S, Bailey JR (2016) Hepatitis C virus resistance to broadly neutralizing antibodies measured using replication competent virus and pseudoparticles. J Gen Virol 97 (11):2883–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey JR, Flyak AI, Cohen VJ, Li H, Wasilewski LN, Snider AE et al. (2017) Broadly neutralizing antibodies with few somatic mutations and hepatitis C virus clearance. JCI Insight 2(9):92872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urbanowicz RA, McClure CP, King B, Mason CP, Ball JK, Tarr AW (2016) Novel functional hepatitis C virus glycoprotein isolates identified using an optimized viral pseudotype entry assay. J Gen Virol 97:2265–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]