ABSTRACT

Ionizing radiation is widely used in medicine and is valuable in both the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases. However, its health effects are ambiguous. Here, we report that low-dose ionizing radiation has beneficial effects in human amyloid-β42 (Aβ42)-expressing Drosophila Alzheimer's disease (AD) models. Ionizing radiation at a dose of 0.05 Gy suppressed AD-like phenotypes, including developmental defects and locomotive dysfunction, but did not alter the decreased survival rates and longevity of Aβ42-expressing flies. The same dose of γ-irradiation reduced Aβ42-induced cell death in Drosophila AD models through downregulation of head involution defective (hid), which encodes a protein that activates caspases. However, 4 Gy of γ-irradiation increased Aβ42-induced cell death without modulating pro-apoptotic genes grim, reaper and hid. The AKT signaling pathway, which was suppressed in Drosophila AD models, was activated by either 0.05 or 4 Gy γ-irradiation. Interestingly, p38 mitogen-activated protein-kinase (MAPK) activity was inhibited by exposure to 0.05 Gy γ-irradiation but enhanced by exposure to 4 Gy in Aβ42-expressing flies. In addition, overexpression of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a negative regulator of the AKT signaling pathway, or a null mutant of AKT strongly suppressed the beneficial effects of low-dose ionizing radiation in Aβ42-expressing flies. These results indicate that low-dose ionizing radiation suppresses Aβ42-induced cell death through regulation of the AKT and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, suggesting that low-dose ionizing radiation has hormetic effects on the pathogenesis of Aβ42-associated AD.

KEY WORDS: Amyloid-β42, Alzheimer's disease, Drosophila, Low-dose ionizing radiation

Summary: Low-dose ionizing radiation can reduce cell death by regulating AKT/p38 signaling pathway and improve Aβ42-induced symptoms in Drosophila Alzheimer's disease, suggesting that low-dose ionizing radiation may be applicable for treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease and is characterized by the presence of amyloid plaques, intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, progressive neuronal loss and gradual memory deterioration (Dickson, 2001; Selkoe, 2001). A major component of amyloid plaques is the aggregation of amyloid-β42 (Aβ42) protein, a pathological hallmark of AD brains (Mattson, 2004; Walsh and Selkoe, 2004). The abnormal accumulation of Aβ42, produced from amyloid precursor protein (APP), results in neuronal cell death (Yankner et al., 1990; Calhoun et al., 1998; Wei et al., 2002). Aβ42-mediated cell death in the brains of both AD patients and animal AD models has been linked to various molecular signals including activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) such as p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), as well as suppression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) (Zhu et al., 2001; Pearson et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2007; Young et al., 2009; Sofola et al., 2010; Tare et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2011; Povellato et al., 2013). These pathways are being explored as potential drug targets in the treatment of AD, such as inhibition of the AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway, for example (Van Dam and De Deyn, 2017).

To date, several drug candidates have been developed to treat AD (Mangialasche et al., 2010). N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor antagonists (e.g. memantine) have been used successfully to improve AD symptoms (Mangialasche et al., 2010). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. Donepezil) have been effective in significantly improving cognitive impairments of AD patients (Van Dam and De Deyn, 2017). However, even with multiple drug treatments, AD patients experience progressive neuronal degeneration. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD remain insufficiently characterized to identify accurate diagnostic markers and therefore potential drug targets (Van Dam and De Deyn, 2017).

Recently, positron emission tomography radiotracers to image amyloid plaques have been developed and approved for clinical use in the evaluation of suspected neurodegenerative diseases, including AD (Mallik et al., 2017). Intriguingly, low-level irradiation, in addition to its use as a diagnostic tool, is an emerging therapeutic technology and has been applied to several models of neurodegenerative disease (Song et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2013; Farfara et al., 2015; Johnstone et al., 2016). Several studies utilizing low-dose ionizing radiation in Aβ-treated mouse hippocampal neurons and the rat hippocampus suggest a potential role for low-dose ionizing radiation in AD treatment (Meng et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2017). However, in vivo studies examining the effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on AD outcomes are still insufficient.

Drosophila melanogaster, powerful genetic and cell biological model organisms, have been used in low-dose ionizing radiation research (Seong et al., 2011; Seong et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2015). In addition, Drosophila AD models are established, which have been useful in studying the etiology of human AD (Shulman et al., 2003; Finelli et al., 2004; Bier, 2005; Iijima-Ando and Iijima, 2010; Hong et al., 2012; Lenz et al., 2013). As Drosophila AD models demonstrate various easily-quantifiable phenotypes, such as eye and wing degeneration, locomotive dysfunction, shortened lifespan and developmental defects, they have been useful in the identification of AD-associated genes and pathways and in evaluating possible candidate drugs for AD treatment (Shulman et al., 2003; Blard et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2008; Rival et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013a,b; Xiong et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015).

In the current study, Drosophila AD models were employed to investigate the effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on disease outcomes including AD-like phenotypes, such as developmental defects and locomotive dysfunction. Interestingly, low-dose ionizing radiation improved partially the AD-like phenotypes and reduced cell death by regulating AKT/p38 signaling pathway. These results suggest that low-dose ionizing radiation may exert beneficial effects on AD.

RESULTS

Low-dose ionizing radiation suppresses Aβ42-induced morphological defects

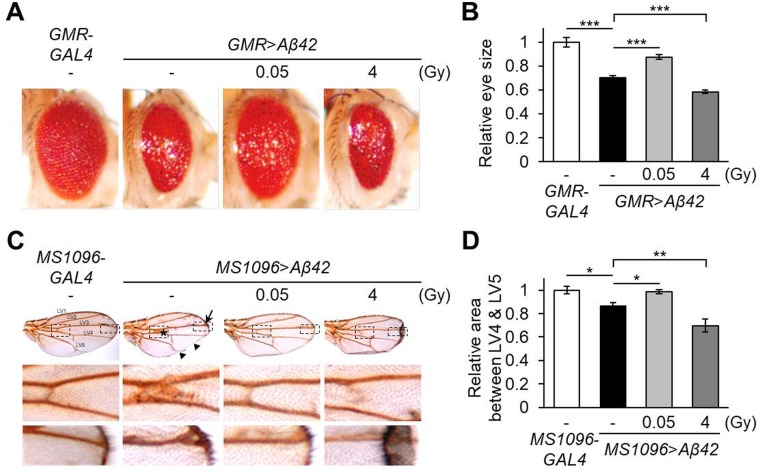

Ectopic expression of human Aβ42 in the Drosophila developing eye, induced by the GMR-GAL4 driver or wing, induced by the MS1096-GAL4 driver, results in a strong rough-eye phenotype or defective vein formations, respectively, indicating cytotoxicity (Hong et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013a,b; Liu et al., 2015). In the current study, we used these human Aβ42-expressing Drosophila AD models to investigate the effects of low-dose ionizing radiation. When Aβ42 was expressed in developing eyes (GMR>Aβ42), eye size was decreased to 70.1% (P=4.72E-05) compared to wild-type controls (GMR-GAL4) (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, the Aβ42-induced reduction in eye size was rescued significantly to 87.5% (P=0.00196) with administration of low-dose γ-irradiation, 0.05 Gy, but not with high-dose, 4 Gy (Fig. 1A,B). Similarly, in the wing-specific Aβ42-expressing flies (MS1096>Aβ42), 0.05 Gy of γ-irradiation treatment improved Aβ42-induced morphological defects, including thick veins, serration phenotypes (Fig. 1C, arrows) and reduced LV4-LV5 interveinal region (Fig. 1D) compared to the wild-type controls (MS1096-GAL4). However, 4 Gy of γ-irradiation enhanced the wing shrinkage of the Aβ42-expressing flies (Fig. 1C,D). These results suggest that low-dose ionizing radiation has beneficial effects on the developmentally defective phenotypes in Drosophila AD models.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ionizing radiation on morphological phenotypes in human Aβ42-expressing flies. (A) The effects of low-dose (0.05 Gy) or high-dose (4 Gy) ionizing radiation on eye destruction in Aβ42-expressing flies (GMR>Aβ42) were determined. GMR-GAL4 was used as a wild-type control. (B) Graph displays the relative size of eyes in each group (n≥6) compared to GMR-GAL4 control flies. (C) Representative wing images showing the effects of γ-irradiation (0.05 Gy or 4 Gy) on the defective wing formation of Aβ42-expressing flies (MS1096>Aβ42). MS1096-GAL4 was used as a wild-type control. The middle and lower images are magnified images of the two dashed boxes depicted in the upper panels. Asterisk, arrow, and triangles represent thick vein, extra vein and serration phenotypes, respectively. LV, longitudinal veins. (D) Graph shows the relative value by measuring the area between LV4 and LV5 in each wing (n≥6) using Image J freeware software program. The relative areas were calculated by the normalized MS1096-GAL4 control flies. All data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. -, untreated control.

Low-dose ionizing radiation ameliorates Aβ42-induced locomotive dysfunction

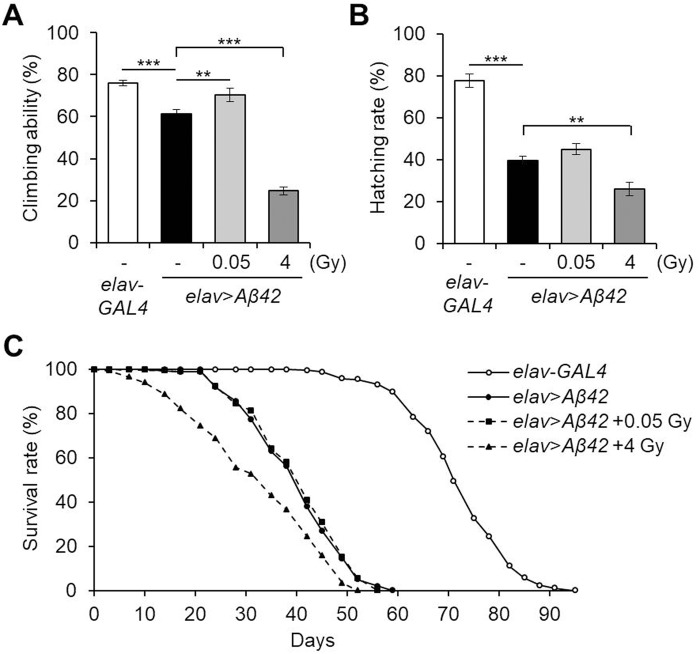

Next, to evaluate the effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on Aβ42-induced Drosophila neurological phenotypes, we examined the motor activity, embryonic survival rate and lifespan in γ-irradiated pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies. As previously reported (Iijima et al., 2004; Hong et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015), Aβ42 pan-neuronal expression, induced by the elav-GAL4 driver (elav>Aβ42), decreased climbing ability, hatching rate and lifespan compared to wild-type controls (elav-GAL4) (Fig. 2). Among these phenotypes, climbing defects were significantly improved by γ-irradiation of 0.05 Gy from 61.3% to 70.3% (P=0.030) (Fig. 2A), but hatching rate (Fig. 2B) and lifespan (Fig. 2C) were not affected. All neuronal phenotypes, including locomotive dysfunction, decreased survival and shortened lifespan, were further deteriorated by administration of 4 Gy of γ-irradiation (Fig. 2). These results indicate that low-dose ionizing radiation, but not high-dose, can mitigate Aβ42-induced motor defects without harm to the survival and longevity of Drosophila in these AD models.

Fig. 2.

Effects of ionizing radiation on locomotive dysfunction and survival rate of pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies. (A) The effects of low-dose (0.05 Gy) or high-dose (4 Gy) ionizing radiation on locomotive defects of pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies (elav>Aβ42) were determined. The climbing ability of 3-day-old flies in each group were determined (n=10). (B,C) Embryonic hatching rates (n=5) (B) and adult survival rates (n≥260) (C) of Aβ42-expressing flies (elav>Aβ42) after exposure to γ-irradiation (0.05 Gy or 4 Gy). elav-GAL4 was used as a wild-type control. All data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. -, untreated control.

Low-dose ionizing radiation improves Aβ42-induced cell death but does not alter the expression of Aβ42

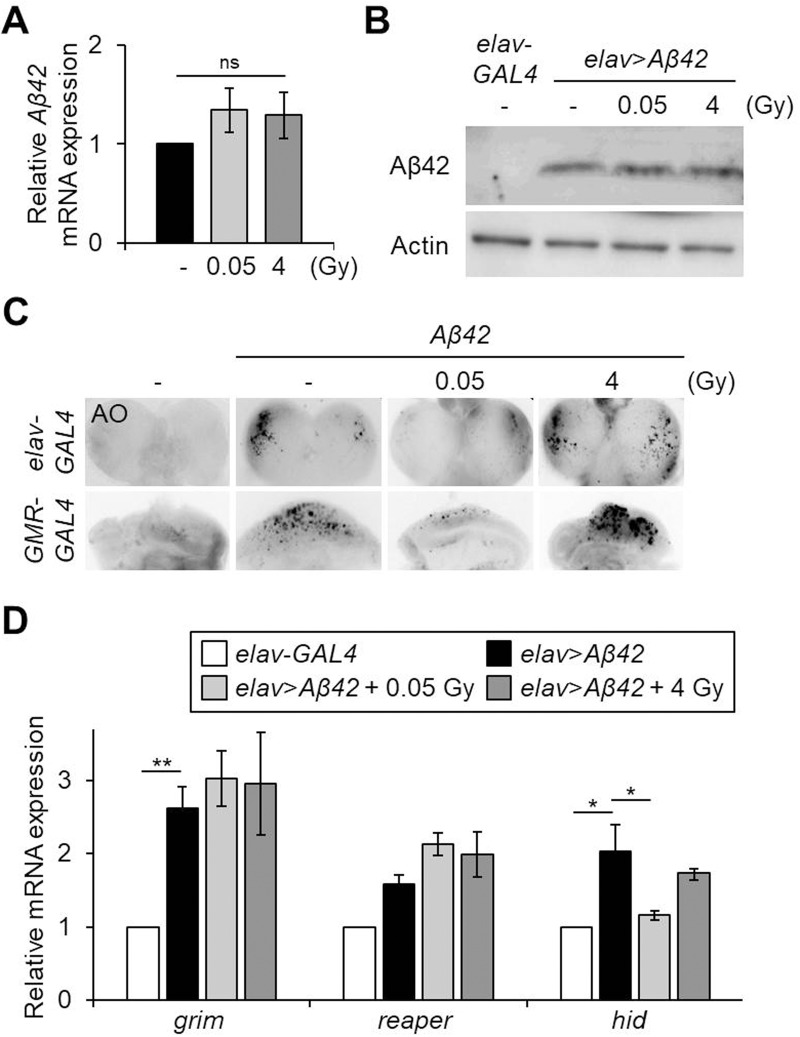

As Aβ42 accumulation and neuronal cell death are important processes in the pathogenesis of AD (Wirths et al., 2004), we next examined if γ-irradiation treatment affected Aβ42 protein expression and cell death in the pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies. As shown Fig. 3A,B, Aβ42 mRNA and protein levels were not altered by γ-irradiation, either 0.05 Gy or 4 Gy, suggesting that the improved or aggravated phenotypes induced by these doses of ionizing radiation, respectively, are not due to the transcription or expression of Aβ42. To investigate the effect of γ-irradiation on Aβ42-induced cell death, Acridine Orange (AO) staining was performed in the larval brain (pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies driven by the elav-GAL4 driver) and eye disc (eye-specific Aβ42-expressing flies driven by the GMR-GAL4 driver) (Fig. 3C). As previously reported (Liu et al., 2015), Aβ42 expression in neurons or the developing eye induced a high level of cell death, while no prominent cell death was detected in the wild-type controls (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, Aβ42-induced cell death was strongly suppressed by 0.05 Gy of γ-irradiation and increased by 4 Gy of γ-irradiation (Fig. 3C). In addition, among pro-apoptotic genes, the head involution defective (hid) upregulation induced in the pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies was suppressed by γ-irradiation, 0.05 Gy, but not 4 Gy (Fig. 3D). The expression levels of grim and reaper were not altered by either dose of γ-irradiation (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that the beneficial effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on Aβ42-induced phenotypes may be due to a decrease in apoptosis through regulation of hid expression and downstream caspase activation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of ionizing radiation on Aβ42 protein levels, cell death and expression of pro-apoptotic genes in Aβ42-expressing flies. (A,B) Aβ42 mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression in the heads of pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies (elav>Aβ42) after exposure to low-dose (0.05 Gy) or high-dose (4 Gy) of γ-irradiation by western blot. Actin was used as an internal control. (C) AO-stained brains (upper panels) and eye discs (lower panels) of indicated larval groups. (D) Relative mRNA levels of pro-apoptotic genes grim, reaper and hid in the Aβ42-expressing flies (elav>Aβ42) after exposure to γ-irradiation (0.05 Gy or 4 Gy) compared to elav-GAL4 control flies by qPCR (n=3). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. -, untreated control; ns, not significant.

Ionizing radiation mediates AKT and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in Drosophila AD models

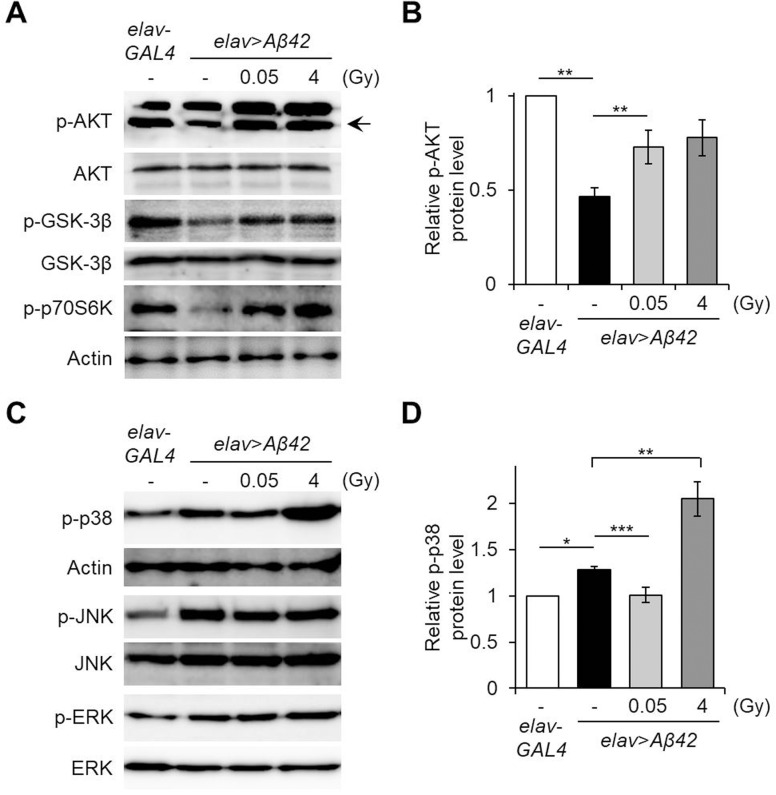

Previous studies report that Aβ42 accumulation induces apoptosis through either inactivation of the AKT/GSK-3β survival signaling pathway (Magrané et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2011) or activation of MAPK signaling pathways such as ERK, JNK and p38 (Perry et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2001). To investigate whether ionizing radiation influences these Aβ42-associated pathways, AKT and MAPK signaling pathway activation was assessed following treatment with ionizing radiation. The levels of downregulated phosphorylation of AKT Ser505, which corresponds with residues of Ser473 in mammalian AKT (Sarbassov et al., 2005), of phospho-GSK-3β and phospho-p70S6K in the pan-neuronal Aβ42-expressing flies (elav>Aβ42) were significantly increased by γ-irradiation treatment of 0.05 Gy and 4 Gy (Fig. 4A,B). Interestingly, the level of upregulated phospho-p38 protein in the Aβ42-expressing flies was reduced by low-dose γ-irradiation, 0.05 Gy, but further elevated by high-dose γ-irradiation, 4 Gy (Fig. 4C,D). There were no discernible differences in either phospho-JNK or phospho-ERK levels between the untreated controls and γ-irradiated Aβ42-expressing flies (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that low-dose ionizing radiation suppresses Aβ42-induced cell death through activation of the AKT survival signaling pathway and inhibition of the p38 MAPK apoptotic pathway. The harmful effects of high-dose ionizing radiation may be attributed to the hyperactivation of p38 MAPK despite activation of AKT. Therefore, balance between the AKT and p38 MAPK signaling pathways is an important factor in the cellular response to ionizing radiation.

Fig. 4.

Effects of ionizing radiation on the AKT survival pathway or MAPK pathway in Aβ42-expressing flies. (A) The levels of phosphorylated (p)-AKT, p-GSK-3β and p-p70S6K in the heads of Aβ42-expressing flies (elav>Aβ42) after exposure to γ-irradiation (0.05 Gy or 4 Gy), compared to elav-GAL4 control flies, determined by western blot. AKT, GSK-3β and actin were used as controls, respectively. (B) Graph shows the relative p-AKT levels in the heads of each group compared to elav-GAL4 control flies (n=4). (C) The levels of p-p38, p-JNK and p-ERK in the heads of indicated groups by western blot. Actin, JNK and ERK were used as controls, respectively. (D) Graph shows the relative levels of p-p38 in the heads of each group compared to elav-GAL4 control flies (n=5). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. -, untreated control.

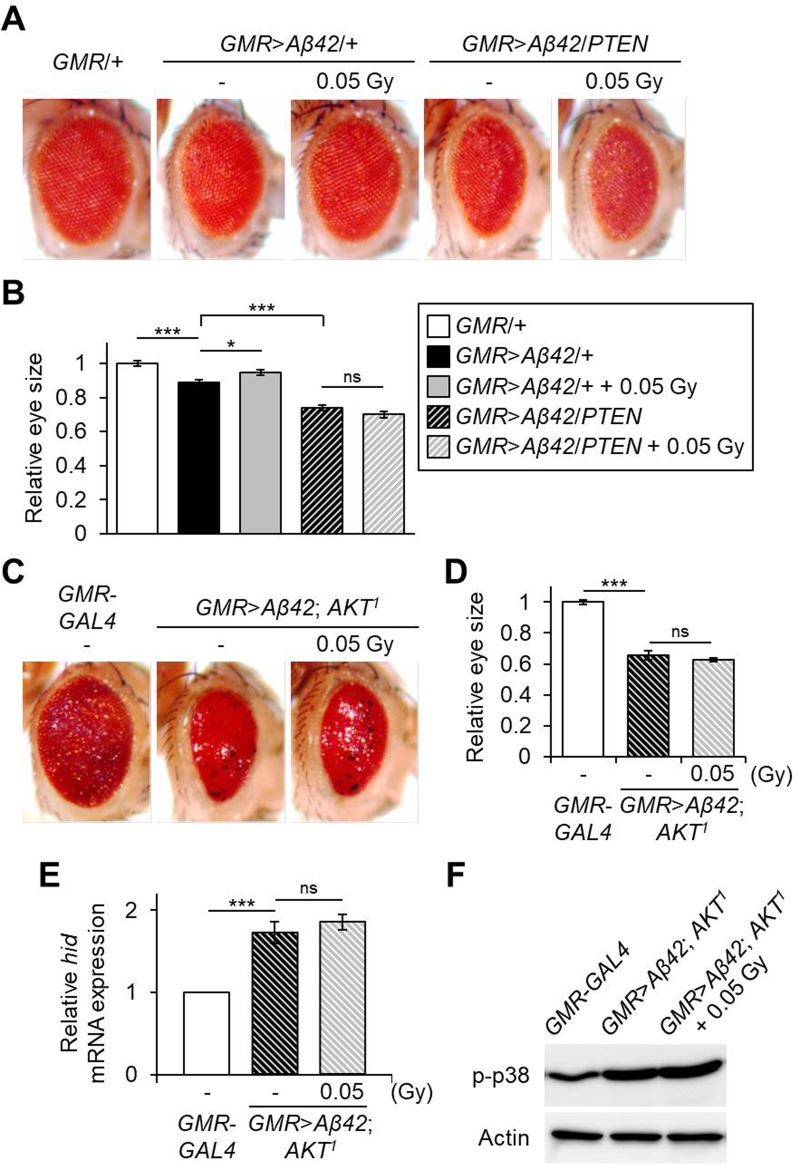

Finally, we investigated whether inhibition of AKT activation could suppress the beneficial effects of low-dose ionizing radiation in the Aβ42-expressing Drosophila AD models. To accomplish this, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a negative regulator of the AKT signaling pathway, was overexpressed along with eye-specific Aβ42-expression. As shown in Fig. 5A,B, eye size of Aβ42- and PTEN-co-expressing flies (GMR>Aβ42/PTEN) was decreased to 83.1% (P=5.54E-06) compared to Aβ42-expressing flies (GMR>Aβ42/+). However, the treatment with γ-irradiation of 0.05 Gy did not improve eye size in the Aβ42- and PTEN-co-expressing flies (Fig. 5A,B). Also, AKT deficiency (AKT1) suppressed the positive effect of low-dose treatment in the eye-specific Aβ42-expressing flies (Fig. 5C,D). In addition, the upregulation of hid and p38 phosphorylation by 0.05 Gy treatment in Aβ42-expressing flies was abolished by AKT deficiency (Fig. 5E,F). Taken together, these results imply that the AKT signaling pathway is important in the response to low-dose ionizing radiation in Aβ42-associated Drosophila AD models.

Fig. 5.

Effects of AKT inhibition on the response to low-dose ionizing radiation in Aβ42-expressing flies. (A) Representative eye images showing the effects of low-dose (0.05 Gy) ionizing radiation on Aβ42-expressing (GMR>Aβ42/+) or Aβ42- and PTEN-co-expressing (GMR>Aβ42/PTEN) flies. GMR/+ was used as a wild-type control. (B) Graph shows the relative size of eyes in each indicated fly group (n≥6) compared to GMR/+ control flies. (C) Representative eye images showing the effects of low-dose (0.05 Gy) ionizing radiation on AKT deficiency (AKT1) in Aβ42-expressing flies. (D) Graph shows the relative size of eyes in each indicated group (n≥6) compared to GMR-GAL4 control flies. (E) Relative mRNA levels of hid in the Aβ42-expressing and AKT mutant flies (GMR>Aβ42; AKT1) after exposure to γ-irradiation of 0.05 Gy compared to GMR-GAL4 control flies by qPCR (n=3). (F) Levels of p-p38 in the heads of indicated groups by western blot. Actin was used as an internal control. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. -, untreated control; ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The effects on exposure to low-dose stresses, even though toxic at higher doses, are still debated (Sohal and Weindruch, 1996; Morimoto and Santoro, 1998; Finkel and Holbrook, 2000; Masoro, 2000; Gori and Münzel, 2012). Ionizing radiation is an important emerging therapeutic as well as diagnostic tool in medicine. However, there is controversy as to whether biological effects of low-dose ionizing radiation are beneficial or indifferent (Song et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2013; Farfara et al., 2015; Johnstone et al., 2016; Tang and Loke, 2015). Several studies on radiation hormesis support the hypothesis that low-dose ionizing radiation, generally recognized as 0.1 Gy and below, elicits beneficial cell signaling responses (Macklis and Beresford, 1991; Calabrese and Baldwin, 2000). For example, low-dose ionizing radiation stimulates various cell survival-related biological responses including DNA repair and the immune system (Gori and Münzel, 2012). However, research on the effects of low-dose ionizing radiation have been confined to in vitro studies, thus in vivo evidence is currently insufficient.

To verify the radiation hormetic effects, Drosophila is an ideal model system for studying the biological response to ionizing radiation (Landis et al., 2012; Moskalev et al., 2015). We previously reported that low-dose ionizing radiation enhances locomotive behavior and extends lifespan in wild-type Drosophila (Seong et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2015). In the present study, we confirmed the effects on low-dose ionizing radiation in human Aβ42-expressing Drosophila AD models. Our results demonstrated that low-dose γ-irradiation, 0.05 Gy, rescued AD-like phenotypes, including morphological defects, motor dysfunction and cell death, without compromising survival rates, embryonic hatching rates or adult lifespan. Similarly, several studies using mouse models showed that ionizing radiation is a potential therapeutic in AD (Marples et al., 2016). Opposing arguments exist that claim that low-dose ionizing radiation is actually a potential risk factor for AD. However, there are no reports of pathological or genetic data associating exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation with increased AD to date (Lowe et al., 2009). Recently, a case study reported improvements in symptoms of an AD patient after radiation exposure (Cuttler et al., 2016). Our data support the hypothesis that low-dose ionizing radiation produces beneficial effects, stimulating the activation of survival mechanisms that protect against AD.

Several recent reports suggest that cell protection-associated proteins, such as the serine/threonine kinase AKT, are associated with the molecular response to ionizing radiation exposure (Liang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). We have also reported that low-dose ionizing radiation alleviates apoptosis through the AKT and MAPK pathways (Kim et al., 2007; Park et al., 2009; Park et al., 2013a,b; Park et al., 2015). In addition, upregulation of the AKT/GSK3 signaling pathway attenuates Aβ42-induced apoptosis (Lee et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2011). As there is a pronounced decrease in AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway activation in AD models (Magrané et al., 2005; Povellato et al., 2013), we hypothesized that low-dose ionizing radiation modulates cell death through the AKT survival signaling pathway in Aβ42-expressing AD models. Indeed, AKT, GSK-3β and p70S6K, which are suppressed in Aβ42-expressing flies, were increased and Aβ42-induced cell death was markedly reduced by γ-irradiation of 0.05 Gy. Additionally, inhibition of the AKT signaling pathway strongly suppressed the positive effects of low-dose ionizing radiation in Aβ42-expressing flies. These findings suggest that the AKT survival pathway mediates ionizing radiation-induced effects in Aβ42-expressing AD models. Low-dose ionizing radiation protects flies against Aβ42-induced cell death, at least in part, through activation of the AKT/GSK-3β/p70S6K signaling pathway.

We also demonstrated that p38 phosphorylation in Aβ42-expressing flies was further increased by high-dose γ-irradiation (4 Gy), as opposed to the suppression seen with low-dose γ-irradiation (0.05 Gy). Hyperactivation of p38 MAPK in AD models has been shown to result in apoptosis (Zhu et al., 2002; Ashabi et al., 2013; Xue et al., 2014). Consistent with this, our studies indicated that γ-irradiation of 4 Gy induced strong cell death, potentially resulting from the upregulation of p38 MAPK, despite activation of AKT signaling.

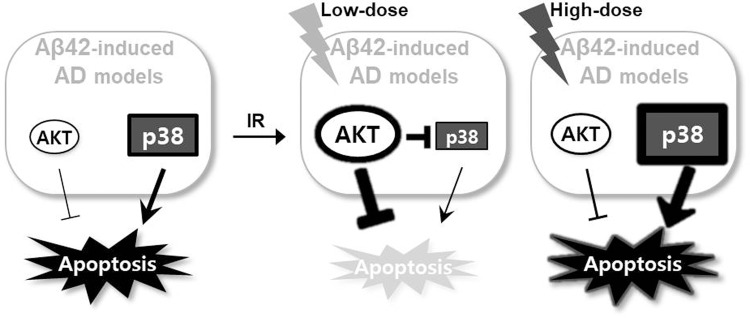

These findings in the Drosophila AD models characterize the biological response to ionizing radiation treatment and a proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 6. In Aβ42-associated AD models, Aβ42 accumulation induces cell death via AKT inhibition and p38 activation. Low-dose ionizing radiation inhibits cell death in the Aβ42-induced AD models. This protection results from activation of the AKT survival signaling pathway, inhibiting cell death, and suppression of p38 activation. However, high-dose ionizing radiation, despite activation of AKT signaling, induces hyper-activated p38 leading to increased cell death. This regulation of AKT activation might play an important role in the beneficial effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on AD model outcomes. Further studies are necessary to dissect ionizing radiation-induced regulation of AKT and p38 MAPK signaling pathways and the regulatory mechanisms involved in the physiological protection against AD.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the cellular response to ionizing radiation in Aβ42-induced AD models. Balancing between AKT and p38 pathway activation controls cellular responses to low- or high-dose ionizing radiation. Low-dose ionizing radiation induces beneficial effects against Aβ42-induced apoptosis through activation of AKT signaling and suppression of the p38 pathway in Aβ42-associated AD models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains

Glass multimer reporter (GMR)-GAL4 (eye driver), embryonic lethal abnormal vision (elav)-GAL4 (pan-neuronal driver), UAS-Aβ42 and UAS-PTEN were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (stock numbers 9146, 8760, 33770 and 8549, respectively; Bloomington, IN, USA). MS1096-GAL4 was generously provided by Dr M. Freeman (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK) and is listed in Flybase. AKT1 was obtained from Dr A. S. Manoukian (University of Toronto, Canada) (Staveley et al., 1998). All fly strains were maintained at 25°C and 60% humidity.

γ-irradiation

γ-irradiation exposures were conducted as previously described (Kim et al., 2015), with some modification. Briefly, 0–6 h embryos were collected and immediately exposed to low-dose (0.05 Gy) and high-dose (4 Gy) ionizing radiation at a dose rate of 0.0159 Gy/s using a 137Cs γ-irradiator (Best Theratronics Ltd., Ottawa, ON, Canada). Both γ-irradiated embryos and non-irradiated control embryos were maintained in the same incubator at 25°C and 60% humidity.

Analysis of Drosophila eyes and wings

External eye and wing morphologies were observed under dissecting microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). To observe the wing vein, wings were isolated from the flies’ bodies by cutting the proximal portion. Wings were mounted in Gary's Magic Mountant solution (1.5 g Canada balsam in 1 ml methyl salicylate) on a slide glass and then it was coverslipped as previously described (Hwang et al., 2010). The size of each eye and the scores or area between longitudinal vein 4 and 5 in each wing were gauged with six or more flies per genotype using Image J freeware software program (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij) (Abramoff et al., 2004).

Climbing assay

The climbing assay was performed as previously described (Hwang et al., 2013). Ten male flies of the indicated lines were transferred to an empty vial and incubated for 1 h at room temperature for environmental acclimation. After tapping the flies down to the bottom, the number of flies that climbed to the top of the vial within 4 s were counted. Ten trials were conducted for each group and the experiment was repeated ten times. Climbing scores (ratio of the number of flies that climbed to the top to the total number of flies, expressed as a percentage) represented the mean climbing score for ten repeated tests.

Analysis of Drosophila development

Sixty embryos of each genotype were placed on grape juice agar plates. After exposure to γ-irradiation, the number of hatched larvae was counted to determine embryonic lethality. Experiments were repeated five times with 60 flies per genotype.

AO staining

AO staining was conducted as previously described, with some modifications (Hwang et al., 2013). The brain and eye imaginal discs were dissected from stage L3 larvae in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). In order to characterize the effects of γ-irradiation on cell death, the brain and eye discs were then incubated for 5 min in 1.6×10−6 M AO (Sigma-Aldrich) and briefly rinsed in PBS. The samples were subsequently observed under an Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Immunoblotting

For western blotting, total protein from 20 heads of 3-day-old flies was isolated from each indicated group and subjected to SDS-gel electrophoresis. Following transfer, membranes were probed with antibodies to Aβ42 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), actin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa city, IA, USA), GSK-3β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), phospho-Drosophila AKT (Ser505), AKT, phospho-GSK-3α/β (Ser21/9), phospho-Dp70S6K (Thr398), phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), ERK, phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) or JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). Western blot analyses were conducted using standard procedures with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

For qPCR, total RNA from 20 fly heads was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. qPCR was performed using Step ONE Plus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and the following primer pairs: grim, 5′-TTTGGGATTTTCTGGGAAAG-3′ and 5′-CCTCCTCATGTGTCCATACC-3′; reaper, 5′-ACCCAAAACCCAAACACAGT-3′ and 5′-TTGTGGCTCTGTGTCCTTGA-3′; hid, 5′-CAGGAGCGAAAGCAGAAAGT-3′ and 5′-TCGTGTATGTTGGCTGTTTG-3′; actin, 5′-TACCCCATTGAGCACGGTAT-3′ and 5′-CACACGCAGCTCATTGTAGA-3′. Quantification was performed using the ′delta-delta Ct′ method to normalize to actin transcript levels and control samples. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Relative levels of mRNA were analyzed by Student's t-test.

Statistical analyses

Drosophila eye or wing size and western blotting densitometry data were quantified with Image J freeware software program (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij) (Abramoff et al., 2004). The Student t-test (two-tailed) was applied for statistical significance within two groups. For comparisons of three or more groups, data was quantitatively analyzed using a one-way ANOVA by Sigma Plot 13.0 (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). For analysis of lifespan, the Kaplan–Meier estimator and the log-rank test were conducted on the pooled cumulative survival data using Online Application Survival Analysis Lifespan Assays (http://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis) (Yang et al., 2011).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.H., S.Y.N.; Formal analysis: S.H., H.J., E.-H.H., H.M.J.; Writing - original draft: S.H., S.Y.N.; Writing - review & editing: S.H., K.S.C., S.Y.N.; Supervision: S.Y.N.; Project administration: S.Y.N.

Funding

This work was supported by grant number 20131610101840 from the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE), Republic of Korea.

References

- Abramoff M. D., Magalhaes P. J. and Ram S. J. (2004). Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 11, 36-42. [Google Scholar]

- Ashabi G., Alamdary S. Z., Ramin M. and Khodagholi F. (2013). Reduction of hippocampal apoptosis by intracerebroventricular administration of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase and/or p38 inhibitors in amyloid beta rat model of Alzheimer's disease: involvement of nuclear-related factor-2 and nuclear factor-κB. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 112, 145-155. 10.1111/bcpt.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier E. (2005). Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 9-23. 10.1038/nrg1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blard O., Feuillette S., Bou J., Chaumette B., Frébourg T., Campion D. and Lecourtois M. (2007). Cytoskeleton proteins are modulators of mutant tauinduced neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 555-566. 10.1093/hmg/ddm011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese E. J. and Baldwin L. A. (2000). Radiation hormesis: its historical foundations as a biological hypothesis. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 19, 41-75. 10.1191/096032700678815602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun M. E., Wiederhold K.-H., Abramowski D., Phinney A. L., Probst A., Sturchler-Pierrat C., Staufenbiel M., Sommer B. and Jucker M. (1998). Neuron loss in APP transgenic mice. Nature 395, 755-756. 10.1038/27351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Song H.-J., Gangi T., Kelkar A., Antani I., Garza D. and Konsolaki M. (2008). Identification of novel genes that modify phenotypes induced by Alzheimer's β-amyloid overexpression in Drosophila. Genetics 178, 1457-1471. 10.1534/genetics.107.078394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttler J. M., Moore E. R., Hosfeld V. D. and Nadolski D. L. (2016). Treatment of Alzheimer disease with CT scans: a case report. Dose Response 14, 1559325816640073 10.1177/1559325816640073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson D. W. (2001). Neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 17, 209-228. 10.1016/S0749-0690(05)70066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farfara D., Tuby H., Trudler D., Doron-Mandel E., Maltz L., Vassar R. J., Frenkel D. and Oron U. (2015). Low-level laser therapy ameliorates disease progression in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 55, 430-436. 10.1007/s12031-014-0354-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finelli A., Kelkar A., Song H.-J., Yang H. and Konsolaki M. (2004). A model for studying Alzheimer's Abeta42-induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26, 365-375. 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. and Holbrook N. J. (2000). Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408, 239-247. 10.1038/35041687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori T. and Münzel T. (2012). Biological effects of low-dose radiation: of harm and hormesis. Eur. Heart J. 33, 292-295. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y. K., Lee S., Park S. H., Lee J. H., Han S. Y., Kim S. T., Kim Y.-K., Jeon S., Koo B.-S. and Cho K. S. (2012). Inhibition of JNK/dFOXO pathway and caspases rescues neurological impairments in Drosophila Alzheimer's disease model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 49-53. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S., Kim D., Choi G., An S. W., Hong Y. K., Suh Y. S., Lee M. J. and Cho K. S. (2010). Parkin suppresses c-Jun N-terminal kinase-induced cell death via transcriptional regulation in Drosophila. Mol. Cells 29, 575-580. 10.1007/s10059-010-0068-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S., Song S., Hong Y. K., Choi G., Suh Y. S., Han S. Y., Lee M., Park S. H., Lee J. H., Lee S. et al. (2013). Drosophila DJ-1 decreases neural sensitivity to stress by negatively regulating Daxx-like protein through dFOXO. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003412 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima-Ando K. and Iijima K. (2010). Transgenic Drosophila models of Alzheimer's disease and tauopathies. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 245-262. 10.1007/s00429-009-0234-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima K., Liu H.-P., Chiang A.-S., Hearn S. A., Konsolaki M. and Zhong Y. (2004). Dissecting the pathological effects of Abeta42 Drosophila: A potential model for Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6623-6628. 10.1073/pnas.0400895101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone D. M., Moro C., Stone J., Benabid A.-L. and Mitrofanis J. (2016). Turning on lights to stop neurodegeneration: the potential of near infrared light therapy in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Front. Neurosci. 9, 500 10.3389/fnins.2015.00500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. S., Kim J. K., Nam S. Y., Yang K. H., Jeong M., Kim H. S., Kim C. S., Jin Y. W. and Kim J. (2007). Low-dose radiation stimulates the proliferation of normal human lung fibroblasts via a transient activation of Raf and Akt. Mol. Cells 24, 424-430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. S., Seong K. M., Lee B. S., Lee I. K., Yang K. H., Kim J.-Y. and Nam S. Y. (2015). Chronic low-dose γ-irradiation of Drosophila melanogaster larvae induces gene expression changes and enhances locomotive behavior. J. Radiat. Res. 56, 475-484. 10.1093/jrr/rru128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis G., Shen J. and Tower J. (2012). Gene expression changes in response to aging compared to heat stress, oxidative stress and ionizing radiation in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging (Albany NY) 4, 768-789. 10.18632/aging.100499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-K., Kumar P., Fu Q., Rosen K. M. and Querfurth H. W. (2009). The insulin/Akt signaling pathway is targeted by intracellular beta-amyloid. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1533-1544. 10.1091/mbc.e08-07-0777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz S., Karsten P., Schulz J. B. and Voigt A. (2013). Drosophila as a screening tool to study human neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurochem. 127, 453-460. 10.1111/jnc.12446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X., Gu J., Yu D., Wang G., Zhou L., Zhang X., Zhao Y., Chen X., Zheng S., Liu Q. et al. (2016). Low-dose radiation induces cell proliferation in human embryonic lung fibroblasts but not in lung cancer cells: importance of ERK1/2 and AKT signaling pathway. Dose Response 14, 1559325815622174 10.1177/1559325815622174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. F., Lee J. H., Kim Y.-M., Lee S., Hong Y. K., Hwang S., Oh Y., Lee K., Yun H. S., Lee I.-S. et al. (2015). In vivo screening of traditional medicinal plants for neuroprotective activity against Aβ42 Cytotoxicity by using Drosophila models of Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 38, 1891-1901. 10.1248/bpb.b15-00459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe X. R., Bhattacharya S., Marchetti F. and Wyrobek A. J. (2009). Early brain response to low-dose radiation exposure involves molecular networks and pathways associated with cognitive functions, advanced aging and Alzheimer's disease. Radiat. Res. 171, 53-65. 10.1667/RR1389.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Wang R., Dong Y., Tucker D., Zhao N., Ahmed M. E., Zhu L., Liu T. C.-Y., Cohen R. M. and Zhang Q. (2017). Low-level laser therapy for beta amyloid toxicity in rat hippocampus. Neurobiol. Aging 49, 165-182. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.-L., Harris-White M. E., Ubeda O. J., Simmons M., Beech W., Lim G. P., Teter B., Frautschy S. A. and Cole G. M. (2007). Evidence of Abeta- and transgene-dependent defects in ERK-CREB signaling in Alzheimer's models. J. Neurochem. 103, 1594-1607. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04869.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklis R. M. and Beresford B. (1991). Radiation hormesis. J. Nucl. Med. 32, 350-359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magrané J., Rosen K. M., Smith R. C., Walsh K., Gouras G. K. and Querfurth H. W. (2005). Intraneuronal beta-amyloid expression downregulates the Akt survival pathway and blunts the stress response. J. Neurosci. 25, 10960-10969. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1723-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A., Drzezga A. and Minoshima S. (2017). Clinical Amyloid Imaging. Semin. Nucl. Med. 47, 31-43. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangialasche F., Solomon A., Winblad B., Mecocci P. and Kivipelto M. (2010). Alzheimer's disease: clinical trials and drug development. Lancet Neurol. 9, 702-716. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marples B., McGee M., Callan S., Bowen S. E., Thibodeau B. J., Michael D. B., Wilson G. D., Maddens M. E., Fontanesi J. and Martinez A. A. (2016). Cranial irradiation significantly reduces beta amyloid plaques in the brain and improves cognition in a murine model of Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Radiother. Oncol. 118, 43-51. 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro E. J. (2000). Caloric restriction and aging: an update. Exp. Gerontol. 35, 299-305. 10.1016/S0531-5565(00)00084-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M. P. (2004). Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature 430, 631-639. 10.1038/nature02621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng C., He Z. and Xing D. (2013). Low-level laser therapy rescues dendrite atrophy via upregulating BDNF expression: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 33, 13505-13517. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0918-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto R. I. and Santoro M. G. (1998). Stress-inducible responses and heat shock proteins: new pharmacologic targets for cytoprotection. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 833-838. 10.1038/nbt0998-833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskalev A., Zhikrivetskaya S., Krasnov G., Shaposhnikov M., Proshkina E., Borisoglebsky D., Danilov A., Peregudova D., Sharapova I., Dobrovolskaya E. et al. (2015). A comparison of the transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster in response to entomopathogenic fungus, ionizing radiation, starvation and cold shock. BMC Genomics 16, S8 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S13-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. S., Yun Y., Kim C. S., Yang K. H., Jeong M., Ahn S. K., Jin Y.-W. and Nam S. Y. (2009). A critical role for AKT activation in protecting cells from ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis and the regulation of acinus gene expression. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 88, 563-575. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., Lee S., Hong Y. K., Hwang S., Lee J. H., Bang S. M., Kim Y.-K., Koo B.-S., Lee I.-S. and Cho K. S. (2013a). Suppressive effects of SuHeXiang Wan on amyloid-β42-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase hyperactivation and glial cell proliferation in a transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 36, 390-398. 10.1248/bpb.b12-00792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. S., Seong K. M., Kim J. Y., Kim C. S., Yang K. H., Jin Y.-W. and Nam S. Y. (2013b). Chronic low-dose radiation inhibits the cells death by cytotoxic high-dose radiation increasing the level of AKT and acinus proteins via NF-κB activation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 89, 371-377. 10.3109/09553002.2013.754560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. S., You G. E., Yang K. H., Kim J. Y., An S., Song J.-Y., Lee S.-J., Lim Y.-K. and Nam S. Y. (2015). Role of AKT and ERK pathways in controlling sensitivity to ionizing radiation and adaptive response induced by low-dose radiation in human immune cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 94, 653-660. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson A. G., Byrne U. T. E., MacGibbon G. A., Faull R. L. M. and Dragunow M. (2006). Activated c-Jun is present in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease brains. Neurosci. Lett. 398, 246-250. 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry G., Roder H., Nunomura A., Takeda A., Friedlich A. L., Zhu X., Raina A. K., Holbrook N., Siedlak S. L., Harris P. L. R. et al. (1999). Activation of neuronal extracellular receptor kinase (ERK) in Alzheimer disease links oxidative stress to abnormal phosphorylation. Neuroreport 10, 2411-2415. 10.1097/00001756-199908020-00035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povellato G., Tuxworth R. I., Hanger D. P. and Tear G. (2013). Modification of the Drosophila model of in vivo Tau toxicity reveals protective phosphorylation by GSK3β. Biol. Open 3, 1-11. 10.1242/bio.20136692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rival T., Page R. M., Chandraratna D. S., Sendall T. J., Ryder E., Liu B., Lewis H., Rosahl T., Hider R., Camargo L. M. et al. (2009). Fenton chemistry and oxidative stress mediate the toxicity of the β-amyloid peptide in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 1335-1347. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06701.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov D. D., Guertin D. A., Ali S. M. and Sabatini D. M. (2005). Phosphorylation and Regulation of Akt/PKB by the Rictor-mTOR Complex. Science 307, 1098-1101. 10.1126/science.1106148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. (2001). Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81, 741-766. 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong K. M., Kim C. S., Seo S.-W., Jeon H. Y., Lee B.-S., Nam S. Y., Yang K. H., Kim J.-Y., Kim C. S., Min K.-J. et al. (2011). Genome-wide analysis of low-dose irradiated male Drosophila melanogaster with extended longevity. Biogerontology 12, 93-107. 10.1007/s10522-010-9295-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong K. M., Kim C. S., Lee B.-S., Nam S. Y., Yang K. H., Kim J.-Y., Park J.-J., Min K.-J. and Jin Y.-W. (2012). Low-dose radiation induces Drosophila innate immunity through Toll pathway activation. J. Radiat. Res. 53, 242-249. 10.1269/jrr.11170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman J. M., Shulman L. M., Weiner W. J. and Feany M. B. (2003). From fruit fly to bedside: translating lessons from Drosophila models of neurodegenerative disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 16, 443-449. 10.1097/01.wco.0000084220.82329.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofola O., Kerr F., Rogers I., Killick R., Augustin H., Gandy C., Allen M. J., Hardy J., Lovestone S. and Partridge L. (2010). Inhibition of GSK-3 ameliorates Abeta pathology in an adult-onset Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001087 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal R. S. and Weindruch R. (1996). Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science 273, 59-63. 10.1126/science.273.5271.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Zhou F. and Chen W. R. (2012). Low-level laser therapy regulates microglial function through Src-mediated signaling pathways: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 219 10.1186/1742-2094-9-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staveley B. E., Ruel L., Jin J., Stambolic V., Mastronardi F. G., Heitzler P., Woodgett J. R. and Manoukian A. S. (1998). Genetic analysis of protein kinase B (AKT) in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 8, 599-603. 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70231-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F. R. and Loke W. K. (2015). Molecular mechanisms of low dose ionizing radiation-induced hormesis, adaptive responses, radioresistance, bystander effects, and genomic instability. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 91, 13-27. 10.3109/09553002.2014.937510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tare M., Modi R. M., Nainaparampil J. J., Puli O. R., Bedi S., Fernandez-Funez P., Kango-Singh M. and Singh A. (2011). Activation of JNK signaling mediates amyloid-β-dependent cell death. PLoS ONE 6, e24361 10.1371/journal.pone.0024361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam D. and De Deyn P. P. (2017). Non human primate models for Alzheimer's disease-related research and drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 12, 187-200. 10.1080/17460441.2017.1271320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. M. and Selkoe D. J. (2004). Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 44, 181-193. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Wang X. and Kusiak J. W. (2002). Signaling events in amyloid beta-peptide-induced neuronal death and insulin-like growth factor I protection. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17649-17656. 10.1074/jbc.M111704200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirths O., Multhaup G. and Bayer T. A. (2004). A modified beta-amyloid hypothesis: intraneuronal accumulation of the beta-amyloid peptide - the first step of a fatal cascade. J. Neurochem. 91, 513-520. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Zhao K., Wu J., Xu Z., Jin S. and Zhang Y. Q. (2013). HDAC6 mutations rescue human tau-induced microtubule defects in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4604-4609. 10.1073/pnas.1207586110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M. Q., Liu X. X., Zhang Y. L. and Gao F. G. (2014). Nicotine exerts neuroprotective effects against β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells through the Erk1/2-p38-JNK-dependent signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 33, 925-933. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.-S., Nam H.-J., Seo M., Han S. K., Choi Y., Nam H. G., Lee S.-J. and Kim S. (2011). OASIS: online application for the survival analysis of lifespan assays performed in aging research. PLoS ONE 6, e23525 10.1371/journal.pone.0023525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner B. A., Duffy L. K. and Kirschner D. A. (1990). Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science 250, 279-282. 10.1126/science.2218531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin G., Li L.-Y., Qu M., Luo H.-B., Wang J.-Z. and Zhou X.-W. (2011). Upregulation of AKT attenuates amyloid-β-induced cell apoptosis. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 25, 337-345. 10.3233/JAD-2011-110104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. F., Pasternak S. H. and Rylett R. J. (2009). Oligomeric aggregates of amyloid beta peptide 1-42 activate ERK/MAPK in SH-SY5Y cells via the alpha7 nicotinic receptor. Neurochem. Int. 55, 796-801. 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Lin X., Yu L., Li W., Qian D., Cheng P., He L., Yang H. and Zhang C. (2016). Low-dose radiation prevents type 1 diabetes-induced cardiomyopathy via activation of AKT mediated anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidant effects. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 20, 1352-1366. 10.1111/jcmm.12823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Castellani R. J., Takeda A., Nunomura A., Atwood C. S., Perry G. and Smith M. A. (2001). Differential activation of neuronal ERK, JNK/SAPK and p38 in Alzheimer disease: the ‘two hit’ hypothesis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 123, 39-46. 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00342-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Lee H.-G., Raina A. K., Perry G. and Smith M. A. (2002). The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in Alzheimer's disease. NeuroSignals 11, 270-281. 10.1159/000067426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]