Abstract

Background

Pregnant people have a risk of carrying a fetus affected by a chromosomal anomaly. Prenatal screening is offered to pregnant people to assess their risk. In recent years, noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) has been introduced clinically, which uses the presence of circulating cell-free fetal DNA in the maternal blood to quantify the risk of a chromosomal anomaly. At present, NIPT is publicly funded for pregnancies at high risk of a chromosomal anomaly, and available to pregnant people at average risk if they choose to pay out of pocket.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of primary, empirical qualitative research that describes the experiences and perspectives of pregnant people, their families, clinicians, and others with lived experience relevant to NIPT. We were interested in the beliefs, experiences, preferences, and perspectives of these groups. We analyzed the evidence available in 36 qualitative and mixed-methods studies using the integrative technique of qualitative meta-synthesis.

Results

Most people (pregnant people, clinicians, and others with relevant lived experience) said that NIPT offered important information to pregnant people and their partners. Most people were very enthusiastic about widening access to NIPT because it can provide information about chromosomal anomalies quite early in pregnancy, with relatively high accuracy, and without risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss. However, many groups cautioned that widening access to NIPT may result in routinization of this test, causing potential harm to pregnant people, their families, the health care system, people living with disabilities, and society as a whole. Widened logistical, financial, emotional, and informational access may be perceived as a benefit, but it can also confer harm on various groups. Many of these challenges echo historical critiques of other forms of prenatal testing, with some issues mitigated or exacerbated by the particular features of NIPT.

Conclusions

Noninvasive prenatal testing offers significant benefit for pregnant people but may also be associated with potential harms related to informed decision-making, inequitable use, social pressure to test, and reduced support for people with disabilities.

BACKGROUND

In this reprt of patient preferences and experiences, we draw on the background included in the health technology assessment1 that is a companion to this qualitative meta-synthesis. We have repeated that background information here, abbreviated to focus on the aspects relevant to patient preferences and experiences of noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT).

Noninvasive prenatal testing is a DNA test of maternal blood that screens pregnancies for common chromosomal anomalies. It uses a blood sample to assess fragments of cell-free fetal DNA that are circulating in the maternal blood. Testing can be done as early as 9 to 10 weeks of pregnancy, but it can also be performed up to birth.2,3

Technology

Noninvasive prenatal testing is a new type of prenatal screening for chromosomal anomalies such as trisomies 21, 18, 13, sex chromosome aneuploidies, and microdeletions (the health technology assessment1 provides a detailed explanation of each of these health conditions). It analyzes fetal DNA obtained from a sample of maternal blood. This cell-free fetal DNA comes mostly from the placenta, and sufficient amounts for analysis can be detected as early as 9 or 10 weeks' gestation. The results of the test are usually available within 10 days (includes processing and shipping time).

Because NIPT is a maternal blood test, there is no risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss, unlike with invasive diagnostic testing such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. However, NIPT is a screening test—not a diagnostic test. As with any screening test, the potential disadvantages of NIPT include false-positive and false-negative results. Although these rates are typically lower than with traditional prenatal screening, it is recommended that NIPT be followed by diagnostic testing such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling before any irrevocable decisions are made about the pregnancy.4 Diagnostic testing may either confirm or refute NIPT results, and should be undertaken for both positive and negative NIPT results, although negative results are typically not confirmed.

Noninvasive prenatal testing can be used as a first-tier test (i.e., for primary screening) or as a second-tier test (i.e., as a contingent or secondary test, after results for positive traditional prenatal screening and before diagnostic testing). However, it is not a comprehensive prenatal testing option. Ultrasound and other serum biomarkers that are part of traditional prenatal screening can detect conditions such as neural tube defects, other fetal structural abnormalities, and placental dysfunction.

Ontario, Canadian, and International Context

Only two tests are available for publicly funded NIPT in Ontario: Harmony and Panorama.2,3 Both tests offer detection of fetal aneuploidies for chromosomes 21, 18, and 13, and the sex chromosomes; sex determination is optional and can be done at no additional cost. The Panorama test also offers testing for a panel of five microdeletions. Pregnant people at average risk for chromosomal anomalies or people who do not meet ministry criteria for funding must pay out of pocket for either test.

Noninvasive prenatal testing is publicly funded only for pregnant people at high risk for fetal anomalies, so cost is one of the main barriers to accessing the test for people at average risk. Because NIPT can be performed earlier than any other traditional prenatal screening option, earlier access to results can allow parents more time to prepare and to make decisions about the course of the pregnancy.5 People who pay out of pocket for NIPT may also make subsequent use of public health care resources such as physician visits, genetic counselling, confirmatory diagnostic testing, and other prenatal services, leading to earlier access to related prenatal services.5

Along with Ontario, British Columbia, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec have confirmed public funding of NIPT for high-risk pregnancies.1 According to a 2016 environmental scan, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Northwest Territories have submitted requests for their governments to consider publicly funding NIPT.6

In the United States, many pregnant people at high risk for fetal aneuploidy are covered for NIPT by commercial and/or public insurance plans. Some insurance companies have expanded their coverage to all pregnant people.7

In Europe, a number of countries (Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Switzerland) fund NIPT as a second-tier (contingent) test.8 At present, Belgium is the only country to publicly fund NIPT as a first-tier test (primary screening), although it reimbursed only from 12 weeks' gestation.9,10

In the United Kingdom, the United Kingdom National Screening Committee has recommended screening with NIPT for high-risk pregnant people because of the high accuracy of NIPT and the potential to avoid diagnostic testing.11

Values and Preferences

In general, pregnant people have supported NIPT as a positive development in prenatal care.12,13 In studies from the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, pregnant people have said that they prefer NIPT over traditional prenatal screening or diagnostic testing because of NIPT's accuracy, early timing, ease of testing, safety, and the comprehensiveness of the information provided.12,14–17 People who had NIPT expressed satisfaction with the test and low decisional regret.17,18

The values and preferences of pregnant people may be different from those of health care providers. For example, in Canada, pregnant people placed greater value on test safety and the comprehensiveness of information, while health care providers placed greater value on accuracy and timing of the results.19

Concerns have also been raised about informed decision-making. Because NIPT is a convenient blood test, its importance and impact may not be accurately conveyed to or understood by patients, resulting in decisions to undergo NIPT that may not be informed or concordant with a person's values. As a result, the offer of NIPT may become routinized in medical practice, and informed decision-making may be jeopardized.13 There is also concern that the ease of testing may lead to increased pressure to test, and then to terminate affected pregnancies, possibly leading to stigmatization of and discrimination against people with disabilities and their families.13,15,20 Broadening the application of NIPT to include new conditions without adequate communication about genetic variability and unknown or variable phenotypic effects is also a concern.

Guidelines

A variety of disciplines such as obstetrics and gynecology, medical genetics, and genetic counselling have provided guidelines on the use of NIPT. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists published an update in 2017 on prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, noting that NIPT is a highly effective screen for trisomies 21, 18, and 13, and should be offered as a possible screening option where available in Canada or with the understanding that it may not be publicly funded.4

Some guidelines acknowledge that NIPT is an effective screening strategy as a contingent or second-tier test, but many have commented on the lack of data for NIPT as a first-tier test in the general population. None of the guidelines recommend NIPT as a first-tier screening test for sex chromosome aneuploidies or microdeletion syndromes. Other common themes in the guideline recommendations include the importance of patient choice for prenatal screening or testing, obtaining informed consent, and appropriate counselling on prenatal testing and the possible test results. A guideline on best ethical practices for clinicians who provide NIPT, and for manufacturers who offer NIPT, was published in 2013.21

Research Question

What are the perspectives, experiences, and preferences of pregnant people, their families, clinicians, and others with rich lived experiences of NIPT?

METHODS

Research questions are developed by Health Quality Ontario in consultation with experts, end users, and/or applicants in the topic area.

Sources

We performed a literature search on September 15, 2017, using Ovid MEDLINE and EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) for studies published from January 1, 2007, to the search date, and on September 21, 2017, in ISI Web of Science Social Sciences Citation Index for studies published from January 1, 2007, to the search date. The search was updated monthly, and eligible studies were incorporated into the analysis as the work proceeded.

Search strategies were developed by medical librarians using medical subject headings (MeSH). To identify qualitative research, we developed a qualitative hybrid filter by combining existing published qualitative filters.22–24 The filters were compared, and redundant search terms were deleted. We added exclusionary terms to the search filter that would be likely to identify quantitative research and reduce the number of false positives. The validation of this filter has been published.25 We applied the qualitative hybrid filter to the search strategies supplied by the medical librarian at Health Quality Ontario.

See Appendix 1 for full details, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

At least two reviewers reviewed each title and abstract and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, we obtained full-text articles.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published between January 1, 2007, and June 1, 2018

Primary qualitative empirical research (using any descriptive or interpretive qualitative methodology, including the qualitative component of mixed-methods studies)

Studies involving adults (> 18 years of age) who had experience with NIPT

Studies involving clinicians or experts on NIPT (i.e., those who offered the test or counselled patients about the test)

Published research work (no theses)

Studies addressing pregnant people and clinicians' experiences of NIPT

Exclusion Criteria

Animal and in vitro studies

Editorials, case reports, or commentaries

Studies that contained quantitative data (i.e., research using statistical hypothesis testing, using primarily quantitative data or analyses, or expressing results in quantitative or statistical terms)

Studies not in English

Studies addressing topics other than NIPT

Studies that included public opinion (i.e., non-experts) about NIPT

Studies that did not include the perspectives of people who had undergone NIPT or had relevant lived experience

Studies that did not pose an empirical research objective or question or involve primary analysis of empirical data

Studies that did not include primary data (e.g., reviews)

Studies that were labelled “qualitative” but did not use a qualitative descriptive or interpretive methodology (e.g., case studies, experiments, or observational analyses using qualitative categorical variables)

Qualitative Analysis

We analyzed published qualitative research using techniques of integrative qualitative meta-synthesis,26–28 also known as qualitative research integration. Qualitative meta-synthesis summarizes research over a number of studies, with the intent of combining findings from multiple articles. The objective of qualitative meta-synthesis is twofold: first, the aggregate of a result reflects the range of findings while retaining the original meaning; second, by comparing and contrasting findings across studies, a new integrative interpretation is produced.

A predefined topic and research question about the perspectives and experiences of pregnant people and clinicians guided the research collection, data extraction, and analysis. We defined topics in stages as relevant literature was identified, and as the corresponding health technology assessment1 proceeded. First, we retrieved all qualitative research relevant to the technology under analysis. Next, we developed a specific research question about the experiences of pregnant people, their families, and clinicians, and performed a final search to retrieve articles relevant to this question. The analysis in this report includes articles that addressed the preferences and perspectives of how women and clinicians or experts (i.e., those who offer or counsel about the test) considered and used NIPT to detect chromosomal aneuploidies—specifically trisomies 21, 18, and 13, sex chromosome aneuploidies, and microdeletions.

Data extraction focused on (and was limited to) findings that were relevant to this research topic. Qualitative findings are the “data-driven and integrated discoveries, judgments, and/or pronouncements researchers offer about the phenomena, events, or cases under investigation.”27 In addition to the researchers' findings, we also extracted original data excerpts (participant quotes, stories, or incidents) to illustrate or communicate specific findings.

Using a staged coding process similar to that of grounded theory,29,30 we broke findings into their component parts (key themes, categories, concepts) and then regrouped them across studies, relating them to each other thematically. This allowed us to organize and reflect on the full range of interpretive insights across the body of research.27,31 We used a constant comparative and iterative approach, in which preliminary categories were repeatedly compared with the research findings, raw data excerpts, and co-investigators' interpretations of the studies.

Quality of Evidence

For valid epistemological reasons, the field of qualitative research lacks consensus on the importance of, and methods or standards for, critical appraisal of research quality.32,33 Qualitative health researchers conventionally under-report procedural details, and the quality of findings tends to rest more on the conceptual prowess of the researchers than on methodological processes.28,33 Theoretically sophisticated findings are promoted as a marker of study quality because they make valuable theoretical contributions to social science academic disciplines.34 However, theoretical sophistication is not necessary to contribute potentially valuable information to a synthesis of multiple studies, or to inform questions posed by the interdisciplinary and interprofessional field of health technology assessment. Qualitative meta-synthesis researchers typically do not exclude qualitative research on the basis of independently appraised “quality.” This approach is common to multiple types of interpretive qualitative synthesis.26,27,31,34–38

For this review, we presumed that the academic peer review and publication processes eliminated scientifically unsound studies, according to current standards. Beyond this, we included all topically relevant, accessible, and published research using any qualitative interpretive or descriptive methodology.

RESULTS

Literature Search

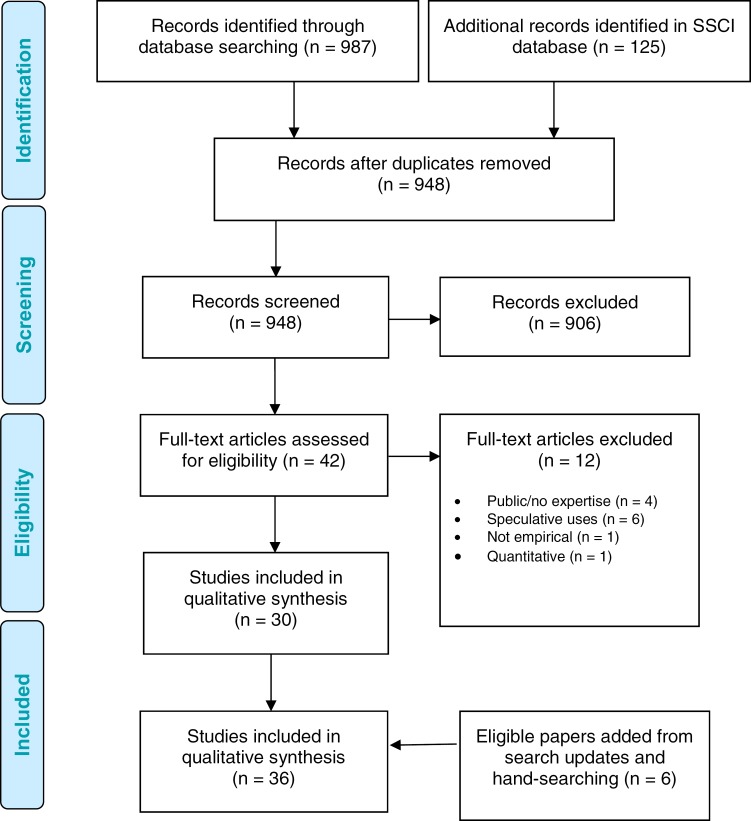

The bibliographic database search yielded 948 citations published between January 1, 2007, and June 1, 2018 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and abstract; each abstract was screened by multiple reviewers according to the criteria listed above. Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA). Search updates yielded an additional six eligible studies.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Abbreviations: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SSCI, Social Sciences Citation Index. Source: Adapted from Moher et al.39

Thirty-six studies met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 describes the study design and methodology of these studies; Table 2 describes where the research was conducted; Table 3 describes the type and number of participants.

Table 1:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|

| Thematic analysis and adapted approaches | 10 |

| Grounded theory and adapted approaches | 10 |

| Content analysis | 7 |

| Not specified | 5 |

| Interpretive content analysis | 2 |

| Interpretive description | 1 |

| Qualitative description | 1 |

| Total | 36 |

Table 2:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Location

| Study Location | Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|

| United States of America | 12 |

| United Kingdom | 9 |

| Netherlands | 4 |

| Canada | 3 |

| Multiple locations | 3 |

| China | 2 |

| Finland | 1 |

| Israel | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Total | 36 |

Table 3:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Participant Type

| Participant Type | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Pregnant people | 1,060 |

| Partners, parents, or family members | 138 |

| Clinicians | 686 |

| Total | 1,884 |

Overview

In our analysis of the qualitative literature, we identified an overarching theme of access. By access, we mean the opportunity to choose NIPT and related technologies, including the opportunity to decline them. If NIPT is chosen, the opportunity to choose also includes the chance to decide what to do with the information from the test. In this analysis we have focused on the opportunity to take action rather than on the action taken, because of the morally challenging nature of the technology and people's desire to engage with it in a variety of ways. As described by several authors,17,40–42 part of the value proposition of NIPT is that it facilitates a range of other technologies, choices, and opportunities, including seeking more information, changing management plans, terminating a pregnancy, or raising a child with a disability.40

In the findings below, we describe the preferences of pregnant people and clinicians for access, and discuss the concerns of these groups about the potential for NIPT to be used in ways that contravene their values. Across the included studies, pregnant people were overwhelmingly in favour of widened access to NIPT because it provides accurate information early in pregnancy without risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss. However, despite this enthusiasm, pregnant people and clinicians voiced many concerns about widening access too far and making NIPT too easy to access. Often, these concerns were abstract and speculative about how others might choose to use the technology.

A terminology note: Not all pregnant people identify as women, but the pregnant participants in the included studies were all described as women. To remain consistent with the way research findings were described by their authors, we have used the term “women” and feminine pronouns here.

Desire for Increased Access to NIPT

Women identified a number of reasons for desiring increased access to NIPT that were quite consistent across studies: better accuracy, less physical risk, and earlier availability of results. In general, pregnant people were supportive of a universal offer of NIPT in the first trimester, regardless of their level of risk for a chromosomal anomaly.43–45

Better Accuracy

How accuracy is understood by women depends on their social location and their values and beliefs about health care. Discussions of accuracy included descriptions of the perceived advantages, disadvantages, limitations, and consequences of prenatal testing.17,40,42–44,46–56 For some, accuracy referred to access to trustworthy and relevant information.54,57 For others, their understanding was strongly influenced by their health care provider's perception of accuracy.55

As well, how the accuracy of prenatal testing is understood and applied influences people's confidence and decision-making. Women actively negotiated between their values about health care and pregnancy, and the characteristics of the testing options.17,40,44,47,50,52,55,57 They sought a testing option that offered the most optimal combination of their values and the highest test accuracy.17,40,44,47,50,52,55,57 In particular, test accuracy played a crucial role in helping women choose a prenatal screening modality.17,44,47,57 For example, some women said that the safety and accuracy of testing and their views on abortion might influence their prenatal testing priorities.44,58 Some reported that the accuracy of NIPT was their highest priority in choosing a prenatal screening modality.17,41,44,46,47,52,55,57–59 Others searched for information about alternative testing options that could provide definitive answers about chromosomal anomalies.40–43,45,47,50–52,55,57,58 Women with twin pregnancies were highly interested in accuracy rates, and in how confident they could be in those rates when carrying a twin pregnancy.60 A small minority of women in many studies said that while NIPT was highly accurate, it was not accurate enough to be worth the time and cost.50,52,55,57,58 The dynamic between the sufficiency and definitiveness of information about prenatal screening is guided by people's values and beliefs pertaining to reproductive health, risk of abnormalities, and understanding of accuracy.

For some women, the high sensitivity and specificity of NIPT was an important part of their preference for the test.43,55,57,59 Confidence in NIPT was linked to women's understanding that it is highly accurate.55 Most women trusted the accuracy information they received, and thought the accuracy of NIPT was satisfactory.43,51,52 A minority preferred the superior accuracy of invasive diagnostic testing—particularly those who were at very high risk of chromosomal anomaly and those who were offered NIPT at an advanced gestational age.17,41,44,52,57 These groups often chose diagnostic testing over NIPT.44,57 The false-positive rate of NIPT was concerning to only a small minority of women; most did not consider it to be an important factor in their interpretation of the trustworthiness of their NIPT results.42,55,57

Less Physical Risk

When considering which test modality to choose, many women described accuracy as a trade-off with risk. For many, the most important aspect of NIPT was the fact that it posed no physical risk to the fetus17,42–44,47,51,52,58,61; some identified this as their main decision-making factor.57,58 The opportunity to gain information about the pregnancy without the risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss was especially important for women who did not conceive easily and used assisted reproduction technologies.60

Women's understanding of the differences between NIPT and invasive diagnostic tests (e.g., amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling) were fairly consistent across studies; most understood that an invasive diagnostic test was required to confirm the results of a screening test like NIPT.42,57 However, the ways women made meaning of the differences between these tests varied significantly both across and within studies. For some, NIPT was accurate enough that they did not feel the need for invasive follow-up testing, especially when they were testing for information only and did not intend to terminate a pregnancy with positive results.62 Women of this view understood NIPT as an alternative to amniocentesis and not as a precursor to it.40 On the other hand, some suggested that NIPT would be beneficial only if amniocentesis were not an option.58 A very small number of women preferred the accuracy of diagnostic testing and were willing to accept the risk of miscarriage.57 However, this was very much the minority view and tended to be expressed by women who had a very high probability of an affected pregnancy.57

Whether NIPT is understood as an alternative or a precursor to invasive diagnostic testing, it offers the opportunity to avoid such testing when NIPT test results are negative. Some women perceived the opportunity to avoid diagnostic testing as the biggest advantage of the test, describing diagnostic testing as “risky and stressful.”56 Some clinicians (genetic counsellors in particular) have witnessed this trend: the advent of NIPT has led to a decrease in the number of diagnostic tests being ordered, rather than a decrease in the number of other screening tests.63 While clinicians saw decreased diagnostic testing as a benefit because it would mean a reduction in miscarriage risk or chance of other complications,64,65 some expressed concern that fewer diagnostic procedures would result in a concurrent loss of ability (i.e., infrastructure and training) to perform such procedures.66

The reduction in physical risk was linked to positive psychological outcomes. The choice of invasive testing was described as a distressing one,61 and the process of invasive testing was worrying and stressful because of the risk of miscarriage.57 By being able to access NIPT and avoid invasive testing, women were able to avoid this anxiety.17,45,57

Earlier Availability of Results

The factors of accuracy and risk are modulated further by when a woman considers prenatal testing.44,57 Women who accessed prenatal testing early in pregnancy (i.e., in the first trimester) said that the features of accuracy, timing of test results, and personal risk of fetal aneuploidy were a higher priority in their decision-making than women who accessed prenatal testing later in pregnancy.17,40,47 Women who were given genetic information earlier had enough time to determine the best course of action for their pregnancy.45,57,58 In turn, these women felt more satisfaction with their decision and better control of their prenatal testing options.47,57 This was not the case for women who accessed prenatal testing later in pregnancy (i.e., mid-second trimester). These women tended to highly value tests that offered results quickly, because their decisions about how to proceed were time-sensitive.47,57 Some expressed dismay that they were not made aware of NIPT earlier in their pregnancy.45 Offering prenatal testing earlier in pregnancy, with appropriate and effective counselling measures, may relieve some of the undue burden and stress for women making decisions about their prenatal health.

The early availability of NIPT was described as a very strong advantage of the test. Women spoke of early access in the context of earlier reassurance42,58,61; more time to prepare emotionally, physically, and financially for raising a child with a disability47,59; earlier maternal–fetal bonding or re-engagement with the pregnancy56,58,61; or earlier termination, which could be both physically and psychologically easier to undergo.40,42,43,45,56–58,61

For many women, the wait time to receive results from NIPT was stressful and unpleasant.17,44,57 Given the potential for “no call” or inconclusive results from NIPT, the wait for results could be anxiety-provoking, especially later in pregnancy when “deadlines” for pregnancy termination approached.57 Given these perceptions of time pressures, many women considering NIPT later in pregnancy were more inclined to opt for invasive testing, which promised conclusive results more quickly.17,57

Preferences for and Perils of Widened Access

While the women who participated in the studies we analyzed were very enthusiastic about increasing access to NIPT, they raised numerous concerns about NIPT being too widely available. We identified a tension between the general support participants expressed for widening access to NIPT and the cautions, worries, or concerns they raised about access that was too wide, or wide in what they saw as the wrong ways. We explored women's and clinicians' preferences for access in four domains (logistical, financial, emotional, informational), paired with a consideration of the potential issues associated with making NIPT so easily available it is experienced as “frictionless.”

By “friction,” we mean the reasons why a patient or clinician would be prompted to stop and consider the gravity and significance of the test. With traditional prenatal testing, this could be the risk of miscarriage or having to schedule multiple appointments. It could also be the cost of NIPT when paid out of pocket.58 These are factors that give people an opportunity to pause and think about whether they truly want to receive the information from the test. These points of friction also provide a foothold if people wish to decline testing. It has been noted for decades in the literature on prenatal testing that women may find it socially difficult to decline a test if they perceive that their physician is recommending it.67 Hanging the decision to decline prenatal testing on a wish to avoid miscarriage or an inability to afford it may be a way for someone to decline a test they do not want.

The metaphor of friction relates to a common concept in bioethics: the “slippery slope.” Slippery slope arguments view actions not in themselves, but as the beginning of a trend. They take the position that if we allow one act or permit one norm that seems relatively harmless, we may open the possibility of further steps “down” the slope, ending in a disastrous outcome.68 Slippery slope arguments are considered by some to be logically fallacious because they rely on emotional appeals, shifting burdens of proof, or distractions.69

The slippery slope metaphor was used implicitly in many of our included studies, likely reflecting the quickly evolving nature of NIPT in the scientific, clinical, commercial, and political arenas. Indeed, the very nature of NIPT is already contested, with clinical practice guidelines and industry patient education documents describing very different uses and possibilities for the test.70 The included studies reflected this uncertainty. When participants were asked to discuss their concerns or worries about NIPT, they frequently described their own worst-case scenarios, which may not have reflected the current state of NIPT use and bore varying resemblance to the implementation options under consideration.56,59

Logistical Aspects of Access

Access can be facilitated logistically: NIPT is a simple procedure that many describe as convenient because it can be done close to home and does not require childcare or time off work for additional appointments.17,43,44,46,52,58 Both clinicians and women commented on the simplicity of the procedure. For clinicians, the simplicity of NIPT made it easier to explain to women.65 Women in many studies remarked that blood tests were normal during pregnancy, and did not represent a barrier to participation.43,44

However, participants in several studies commented that the simplicity of NIPT may undermine informed decision-making. Because there is no physical risk or cost, women may not realize the complexity of the information available from NIPT and the decisions about invasive testing or termination that may follow (i.e., it's “just another blood test”).17,42,43,47,52,56,61 Similarly, women and clinicians recognized the potential for routinization if women perceived NIPT to be a simple blood test71 that was low-risk and easy.58,71,72 Some women expressed a preference for having NIPT the same day as it was introduced in counselling,44,47 but others thought that it occurred too early to provide enough time for an informed decision, recommending time between the initial discussion about NIPT and the procedure itself to allow for reflection and facilitate informed decision-making.47,52,59

Financial Aspects of Access

Access involves financial factors: women in many studies indicated they would be willing to pay privately, and to make significant sacrifices to do so.40,42 The amount of money they would be willing to pay varied significantly, potentially influenced by their socioeconomic status and their understanding of the importance of the test in addressing their pregnancy concerns.42,46,49–51,57,58

However, despite this willingness to pay out of pocket, both women and clinicians recognized the equity issues involved in offering a superior technology only to those with financial resources.42,43,58,60,63,73,74 Government funding (universal or subsidized according to ability to pay) was often suggested as a way of alleviating these inequities.42,45,46,57,58,65,66 While many women were in favour of public funding for NIPT, some recognized that using public funds for NIPT may send a message that the government was encouraging uptake of the test.58,65 Others worried about whether NIPT was the best use of scarce health system resources.45 Clinicians noted that public funding could result in test redundancy, with NIPT used later in pregnancy when more reliable and comprehensive results could be obtained from other tests.43,63 Clinicians also suggested that public funding would increase test uptake and therefore the need for follow-up testing.64,66,71,74 Women were aware of these issues, and concern for use of health system resources was implicit in their discussions of the cost of NIPT compared to existing, publicly funded prenatal tests.45,46,57,58

Emotional and Psychosocial Aspects of Access

“Choose-able” Choices

Noninvasive prenatal testing can facilitate access emotionally and psychosocially by providing information a woman can use to make choices that she feels comfortable with, and that are consistent with her values.40 For example, the fact that NIPT provides information without risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss may allow women who are not considering termination (and so would not choose invasive testing) to obtain information they can use to plan and prepare for the birth and parenting of a child with a disability.58 In other words, with the risk of miscarriage removed, prenatal testing becomes a “choose-able” choice for women who would not want to terminate their pregnancy.

For those who would consider termination, NIPT also offers a choose-able choice, by providing information without visual acknowledgement of the pregnancy, unlike invasive procedures, which are accompanied by ultrasound.46,47 This procedural aspect facilitated women's ability to remain detached from their pregnancy, a psychological defence mechanism that could help them cope better if they eventually chose to terminate the pregnancy.45,57,61 It is important to note that this delayed maternal attachment to pregnancy (or “tentative pregnancy”) is neither a new phenomenon nor one specific to NIPT75; rather, it seems to be enhanced by the advancing prevalence and breadth of prenatal testing exemplified by NIPT.

While some women prefer to avoid the visual acknowledgement of their pregnancy, for others the 12-week ultrasound is an important part of connecting with impending parenthood. Depending on how NIPT is implemented, some women may no longer be offered the first-trimester ultrasound that is currently included as part of first trimester screening or integrated prenatal screening. But some women saw this ultrasound as a benefit, because it provides the opportunity to connect with the idea of becoming a mother.51 Clinicians were also in favour of retaining the 12-week ultrasound for clinical reasons, including the detection of conditions that have implications for pregnancy management but are not detected by NIPT.66

Noninvasive prenatal testing provides choose-able choices in other respects, as well. Prenatal testing early in pregnancy preserves confidentiality and privacy; a woman may not have publicly disclosed her pregnancy yet and so may feel more comfortable pursuing further testing. Because NIPT offers information earlier, it gives people more time to think about whether or not they wish to engage in invasive testing before they run out of time to consider this option.

However, there are also negative emotional and psychosocial factors involved in widened access to NIPT. Wider access may increase social pressure, not only to participate in NIPT but also to terminate affected pregnancies. Sources of pressure to test included public perceptions that NIPT was easy, risk-free, and “just a blood test,”43,47,56,58,59 which could cause women to feel that they are expected to participate in NIPT59 as it becomes increasingly normalized.56 Family members, including partners, may also pressure women to undergo NIPT.46,47,58,61 Women may feel less comfortable declining the test,59 particularly because the absence of physical risk invalidates the risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss as a reason to decline testing.47 Women who have consented to prenatal testing in previous pregnancies may feel pressure to consent to NIPT in future pregnancies.17 Several authors expressed concern that if NIPT becomes normalized, support for or acceptance of people with disabilities40,45,47,65 may decrease, because fewer people will be born with conditions such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21) as a result of termination of affected pregnancies.17,41,47,59 Such social pressure may mean that declining NIPT and other forms of prenatal testing becomes less of a choose-able choice.59,65

Test-Related Anxiety

The concept of “iatrogenic anxiety” was present in several articles: that is, anxiety or worry caused or exacerbated by the availability of tests, the offer of tests, and the consideration of tests. As prenatal testing becomes available for a greater variety of conditions and to more and more women, some may start to experience anxiety about the status of their pregnancy. Indeed, many mentioned a great deal of anxiety,40–43,45,47,51,55,59,60 although this seemed to be related more to prenatal testing in general than to NIPT in particular. Women wanted to know whether their pregnancy was affected as soon as possible, and felt anxiety while waiting for results.41,43,44 Some women felt that the anxiety caused by waiting was greater than fears of miscarriage related to invasive testing.44 Some also indicated that a positive NIPT result could lead to greater worry and anxiety,47,51,59 but this stress would likely exist regardless of testing type.

Iatrogenic anxiety is apparent when we consider how information about test accuracy may increase feelings of anxiety and uncertainty in prenatal testing.17,40–44,47,48,50–52,55,57,62,65 Anxiety and uncertainty may be related to confusion about the accuracy, false-positive, and false-negative rates of prenatal testing.17,41–43,50,51,55,57 Some described prenatal testing as a stressful experience because of uncertainty about false positives or inconclusive results.51,57 One woman said that some of her anxiety around NIPT came from waiting for results knowing that she might not receive conclusive answers, and that she might be forced to make a decision about amniocentesis very quickly: “The chance of not getting a result from the NIPT … to go through the test and to not actually have anything, you know, time is ticking …”57 This uncertainty can be allayed through discussions with an informed health care provider about the limitations of prenatal testing, and comparing NIPT to other testing options.45,46,52,53,62

For some women, worry or anxiety about prenatal testing may stem from uncertainty about the outcomes of their pregnancy in general. Some women expressed concern about how they would cope with the many potential outcomes associated with false-positive and false-negative test results.40,41,47 By preparing for each possible outcome, women experienced significant anxiety, because amid uncertainty about test results, they had to make important health care decisions that would affect them, their children, and their family.40,41,43,44,47,48,55–57,62 On the other hand, dealing with one outcome by receiving definitive test results may lower anxiety and uncertainty by allowing women to make more informed, confident, and simpler decisions about how to manage their pregnancy and postnatal life.

How women coped with iatrogenic anxiety varied. Some women declined testing because they wished to avoid undue stress caused by the anxiety and uncertainty associated with prenatal testing.40,44 Others said that undergoing prenatal testing might reduce their anxiety and uncertainty, because it would provide more information about their health status and pregnancy.40 For the latter group, high test accuracy offered a feeling of more control over their pregnancy and reassurance about prenatal decisions.17,47,50,52,55,56,59,62

Informational Aspects of Access

Access also includes high-quality, trustworthy information and complementary technologies that permit further informed decision-making. Access to information and technologies must be provided in a way that allows everyone to make choices within their value system. Information is also important because high-quality counselling may facilitate informed decision-making in a way that attenuates some of the anticipated challenges of “frictionless” access to NIPT.

Informational Access

Decades of studies about prenatal testing have emphasized the challenge for clinicians of providing complex information to patients in a way that facilitates informed choice. The rapidly evolving nature of NIPT adds an additional challenge to this task. It is unclear to what extent informed decision-making is a problem with NIPT. Typically, women expressed satisfaction with their understanding of NIPT,43,51,52 although some misperceptions were reported with respect to the advanced maternal age threshold,55 accuracy compared to invasive tests,45,51,57 and the distinction between screening and diagnostic tests.51 There was significant discussion about the work women did on their own to obtain information from sources other than their clinicians.42,49,51,52,54–56,60,62,65 Women in many studies were clear that they preferred information to come from their clinicians rather than searching it out themselves.17,43,47,48,55,60,62,76 However, women differed about the role they preferred their clinician to play in their decision-making process. For example, women from Quebec wanted their health care provider to offer information, but did not think that their provider should play a critical role in their decisions.58 Some American women who had been asked to consider expanding applications of NIPT (e.g., microdeletions) wanted their clinicians to recommend a course of action based on their medical expertise, but others preferred that their clinician take the role of a facilitator, guiding their thinking about how their personal values and preferences related to the medical options before them.76

While clinicians recognized the importance of counselling, they noted that providing accurate and comprehensive information about a quickly evolving technology within the time constraints of the clinical encounter is not easy.45,66,71,72 The amount of time it would take to learn about NIPT to counsel patients provoked hesitation among clinicians in adopting the technology.64 As NIPT is adopted into primary care prenatal practice, there will be a significant need to educate health professionals, requiring time and resources.64 While clinicians who were new to NIPT were hesitant about the time it would take to become comfortable counselling patients about it, clinicians who already used NIPT in their clinics were much less concerned.74,77

Clinicians described limitations to their own knowledge of and comfort with NIPT because of a lack of evidence for the technology63,71 and a lack of education and guidelines.64,71,74 Women in many studies echoed these concerns, saying that they were dissatisfied with the information or counselling they received from their clinician.42,46,51,62 Some women felt that their clinician did not have enough knowledge about NIPT to provide counselling.40,42,46,51,62 In particular, some felt that their physicians were unable to provide comprehensible information about testable conditions such as Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18), Patau syndrome (trisomy 13) and sex-linked disorders (e.g., Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome).46,62 Some parents of children with Down syndrome believed that counselling lacked updated and balanced information because of health professionals' unfamiliarity with the condition.56 Some types of clinicians were more likely to be described as less knowledgeable about NIPT, such as family physicians or general practitioners,45 midwives,46 and obstetricians.42 Some women were satisfied with the counselling their clinicians provided about NIPT, finding it trustworthy and sufficient,46,53,61 but these women (and others) were more likely to have seen a specialized clinician, or to express a preference for seeing clinicians with specialized knowledge, such as genetic counsellors and specialized nurses,45,46,60 midwives,17,47 and specialist physicians.47 Some women preferred to receive counselling from the first care provider they saw during pregnancy—in many cases a primary care provider.47 Of course, these opinions may change over time as NIPT becomes more widely adopted and clinicians of all types become more comfortable with counselling. When many of these studies were conducted, NIPT was a new technology, available mostly in tertiary care or through research studies.

Both clinicians and women strongly agreed that not enough time was allotted in consultations to convey all the information needed to facilitate counselling. Patients often had a wide range of questions and concerns, and clinicians did not always have the time to answer these questions, not only for the patients, but also for themselves.47,64,74 Women in one study said that too much information was provided in too short a time.53 This is likely to become a greater challenge as NIPT technology and applications advance.48 When too much information is provided in too short a time, women may feel overwhelmed.43,47,62

Improving Informed Decision-Making

We identified several specific ways to improve informed decision-making. Our analysis indicated that women invest significant effort in seeking information from a variety of sources beyond clinicians, including the media42,52,54,56,65; online sources52 such as discussion groups, websites, and social media42,54,62,65; written materials51,54; friends and family members49,52,55,60,62; videos and phone applications54; support groups46; and academic institutions.42 They were not entirely happy with this mix of sources, expressing a desire for more information from clinicians,17,43,47,48,55,62 websites,48 and support groups.54 Parents of children with Down syndrome also suggested that other parents could act as sources of information for women who were considering how to handle a diagnosis.56 Having the opportunity to talk with a knowledgeable person would provide a chance to correct misunderstandings about prenatal testing and sound out potential scenarios or implications.48,52

From these sources, people sought a wide range of information. Although women generally understood and appreciated the advantages, disadvantages, limitations, and consequences of prenatal testing,44,55,56 they reported a strong need for additional, more trustworthy information about the accuracy of the various prenatal testing options.17,40,42,44,46,48,51,54,56 Women sought more information about the sensitivity and specificity of NIPT,17,40,51,53–55 the implications of a false-positive or false-negative result,43,51,55 the care options available after receiving a positive or negative test result,43,51,53 and the testing option that could provide definitive information about personal risk.51 This request for more information was accompanied by a desire for a clearer discussion about risk ratios, probabilities, and detection rates of testing42; the meaning of inconclusive results17,40,42,48; what NIPT detects and what it does not47–49,51,54; and a comparison of the accuracy of the different prenatal testing options.53

Women and clinicians raised concerns about the quality of information on NIPT that is currently available. These concerns included inadequate information in counselling40,62 and the questionable trustworthiness of online sources.42,62 Authors of multiple studies mentioned concerns about the one-sided nature of knowledge related to the conditions for which NIPT tests. Concerns included a lack of discussion about termination and disability during counselling,50 women's lack of understanding of the conditions detected by NIPT, including Down syndrome,52 other trisomies,52,56 and sex chromosome aneuploidies.48 There was also concern that women and clinicians may both hold an unbalanced view of Down syndrome.41,56

Beyond the important question of how we facilitate information provision and counselling to women, some authors asked whether high-quality evidence about NIPT is available to inform the process. Many clinicians reported low knowledge and confidence in the test.63,64,66,71,72,74 These clinicians desired more definitive, confident, and trustworthy information and evidence about prenatal testing options.63,64,66,71,74 In particular, they desired consensus and clearer guidelines about how to implement NIPT in their practice.74 A minority of women, typically those who were highly educated, also recognized that the evidence for certain prenatal testing options is still evolving.57,62

DISCUSSION

Across the papers included in this review, women overwhelmingly cited three reasons why they wanted increased access to NIPT: it is perceived to be highly accurate; it can be conducted without physical risk to the fetus; and the early availability of NIPT results provides more appealing possibilities for decision-making about other testing and about continuation or termination of the pregnancy. Most women in the studies we analyzed understood that NIPT was a screening test, and that confirmation via invasive diagnostic testing would be required. Even with this understanding, women were enthusiastic about the accuracy of NIPT, although in several studies some raised questions, typically asking about the evidence base, the possibility of false-positive or false-negative results, and the chances of a “no call” or inconclusive result. Many study authors linked these concerns to women who had a higher level of education or knowledge about NIPT. If patient education about NIPT permits disclosure and discussion of accuracy issues with a wider group of women, more women may share these concerns. Although there was general enthusiasm for the accuracy of NIPT, the lack of risk of procedure-related pregnancy loss was also a very important factor; for some women, it was the deciding factor when selecting a prenatal test. Women in several studies described the lack of physical risk as providing information and alleviating stress. Receiving NIPT results earlier in pregnancy had a similar effect; women said they were in a better position to make decisions about the management of their pregnancy when they could access information early. When receiving a negative screening result, women felt they had obtained reassurance much sooner than they would have otherwise. Women who received positive NIPT results had sufficient time to make decisions about invasive testing, and to prepare to either raise a child with disabilities or to terminate the pregnancy.

While the desire for widened access to NIPT was a consistent theme across all papers about women's perspectives, it should not be taken without a caveat. Both women and clinicians raised concerns about what could happen if wider access to NIPT were implemented without careful planning and deliberation. When asked to consider the implementation of NIPT, women and clinicians addressed its simplicity as a procedure; the financial means necessary to access the test; the anxiety surrounding pregnancy and prenatal testing; and the importance of informed decision-making. Both women and clinicians found the procedural simplicity of NIPT to be an advantage, because women could do the test quickly and close to home, while clinicians could explain the test more easily. However, both also recognized that such simplicity creates the potential for routinization and the erosion of informed decision-making. From a financial perspective, many women would have been willing to pay out of pocket for NIPT, stating they were willing to make sacrifices to do so. However, they noted that a test available only to those with the means to afford it would create equity issues. While public funding was suggested as a means of remedying such equity issues, some participants questioned whether publicly funding NIPT was a judicious use of scarce health care resources, and whether it would send the message to women that the government encouraged the identification (and potentially termination) of affected pregnancies. Many women also discussed test-related anxiety, explaining that prenatal testing in general is a very stressful experience and that NIPT could contribute to their stress because of the waiting time for receiving results, as well as the possibility of inconclusive or “no call” results, false positives or false negatives. Even so, most women described NIPT as a technology that provides greater reproductive self-determination.

For women who are not considering termination and would decline invasive testing because of the risk of miscarriage, NIPT offers the opportunity to obtain information about the pregnancy without the risk of procedure-related loss. On the other hand, for women who are considering termination, NIPT is a more appealing test because it does not provide the visual acknowledgement of the pregnancy involved in the ultrasound component of invasive procedures. Finally, both women and clinicians spoke about the importance of informed decision-making around NIPT and reported a strong need for an increased quantity and quality of information about test accuracy, the implications and next steps related to positive or negative results, and the overall utility of NIPT compared with other prenatal testing options. Women were generally satisfied with their understanding of NIPT, but some were disappointed by their health care providers' level of knowledge. This sentiment was echoed by clinicians, some of whom acknowledged the fact that they were not very familiar with NIPT, and emphasized the importance that patients receive counselling from health care providers with specialized knowledge of this technology.

Limitations

Qualitative research provides theoretical and contextual insights into the experiences of limited numbers of people in specific settings. Qualitative research findings are not intended to generalize directly to populations, although meta-synthesis across a number of qualitative studies builds an increasingly robust understanding that is more likely to be transferable. While qualitative insights are robust and often enlightening for understanding experiences and planning services in other settings, the findings of the studies reviewed here—and of this synthesis—do not strictly generalize to the Ontario (or any specific) population. The findings are limited to the conditions included in the body of literature synthesized (i.e., women's and clinicians' perspectives on noninvasive prenatal testing). This evidence must be interpreted and applied carefully, in light of expertise and the experiences of the relevant community.

CONCLUSIONS

We examined 36 empirical primary qualitative research studies that described the perspectives, experiences, and preferences of women and clinicians with respect to noninvasive prenatal testing. From this body of evidence, we found that women are strongly in favour of expanded access to noninvasive testing because they perceive it to be highly accurate, they appreciate that it is not associated with procedure-related pregnancy loss, and it provides results quite early in the pregnancy. However, despite their enthusiasm for broadened access to NIPT, women and clinicians offered many cautions about expanded access to this technology. Without the implementation of supportive counselling, NIPT may become routinized and accepted without careful consideration. It may be accessed inequitably, or universal funding may be perceived as a subtle pressure to test. A social environment in which prenatal testing is the norm may exacerbate anxiety and worry in women. It may decrease the visibility of people with disabilities, and the resources and support available to them. Careful attention to the facilitation of counselling and informed decision-making may help mitigate these potential challenges.

Acknowledgments

This report was developed by a multidisciplinary team from McMaster University at the request of and with in-kind support from Health Quality Ontario.

The medical librarian was Caroline Higgins. The medical editor was Jeanne McKane.

The authors are grateful to the Health Quality Ontario team conducting the healthy technology assessment of noninvasive prenatal testing for their guidance in determining the research question for this report.

The statements, conclusions, and views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the consulted experts.

This report was funded by the Government of Ontario and the Ontario SPOR SUPPORT Unit, which is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Government of Ontario.

APPENDIX: LITERATURE SEARCH STRATEGIES

Database: All Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

Search Strategy:

-

1

Sequence Analysis, DNA/ (145222)

-

2

((DNA or parallel or next-generation or shotgun or target∗) adj sequenc∗).ti,ab,kf. (120098)

-

3

(MPSS or NGS or CSS or TMPS).ti,ab,kf. (13521)

-

4

High-Throughput Nucleotide Sequencing/ (18597)

-

5

((high throughput adj2 (analys#s or sequenc∗)) or single nucleotide polymorphism∗ or SNP or SNPs).ti,ab,kf. (111393)

-

6

or/1-5 (356702)

-

7

Genetic Testing/ (33131)

-

8

((genetic∗ or gene∗1 or genome∗1 or genomic∗) adj2 (test or tests or testing or diagnos#s or screen∗)).ti,ab,kf. (56759)

-

9

or/7-8 (78355)

-

10

(noninvasive∗ or non-invasive∗).ti,ab,kf. (164692)

-

11

9 and 10 (1050)

-

12

6 or 11 (357567)

-

13

Prenatal Diagnosis/ (35758)

-

14

((antenatal or ante-natal or intrauterine or intra-uterine or prenatal or pre-natal) adj2 (test or tests or testing or diagnos#s or detect∗ or screen∗)).ti,ab,kf. (34125)

-

15

(maternal adj2 (plasm∗ or blood)).ti,ab,kf. (12727)

-

16

or/13-15 (64934)

-

17

12 and 16 (2040)

-

18

(((f?etal or f?etus∗ or free-f?etal or placenta∗) adj2 dna) or cell-free dna).ti,ab,kf. (3939)

-

19

(cff DNA or cffDNA or cf DNA or cfDNA or f DNA or fDNA or ff DNA or ffDNA).ti,ab,kf. (1337)

-

20

((noninvasive∗ or non-invasive∗) adj5 (prenatal or f?etal or f?etus∗) adj (test or tests or testing or diagnos#s or detect∗ or screen∗)).ti,ab,kf. (1568)

-

21

(NIPT or NIPD or NIDT or gNIPT or NIPS).ti,ab,kf. (1071)

-

22

or/17-21 (6854)

-

23

Qualitative Research/ (36358)

-

24

Interview/ (28094)

-

25

(theme$ or thematic).mp. (80191)

-

26

qualitative.af. (196605)

-

27

Nursing Methodology Research/ (16995)

-

28

questionnaire$.mp. (627589)

-

29

ethnological research.mp. (7)

-

30

ethnograph$.mp. (9033)

-

31

ethnonursing.af. (143)

-

32

phenomenol$.af. (22661)

-

33

(grounded adj (theor$ or study or studies or research or analys?s)).af. (9737)

-

34

(life stor$ or women∗ stor$).mp. (1169)

-

35

(emic or etic or hermeneutic$ or heuristic$ or semiotic$).af. or (data adj1 saturat$).tw. or participant observ$.tw. (19774)

-

36

(social construct$ or (postmodern$ or post-structural$) or (post structural$ or poststructural$) or post modern$ or post-modern$ or feminis$ or interpret$).mp. (475839)

-

37

(action research or cooperative inquir$ or co operative inquir$ or co-operative inquir$).mp. (3558)

-

38

(humanistic or existential or experiential or paradigm$).mp. (131602)

-

39

(field adj (study or studies or research)).tw. (14432)

-

40

human science.tw. (255)

-

41

biographical method.tw. (16)

-

42

theoretical sampl$.af. (566)

-

43

((purpos$ adj4 sampl$) or (focus adj group$)).af. (50673)

-

44

(account or accounts or unstructured or openended or open ended or text$ or narrative$).mp. (551153)

-

45

(life world or life-world or conversation analys?s or personal experience$ or theoretical saturation).mp. (13987)

-

46

((lived or life) adj experience$).mp. (8674)

-

47

cluster sampl$.mp. (5902)

-

48

observational method$.af. (633)

-

49

content analysis.af. (20465)

-

50

(constant adj (comparative or comparison)).af. (3786)

-

51

((discourse$ or discurs$) adj3 analys?s).tw. (1823)

-

52

narrative analys?s.af. (947)

-

53

heidegger$.tw. (605)

-

54

colaizzi$.tw. (538)

-

55

spiegelberg$.tw. (81)

-

56

(van adj manen$).tw. (335)

-

57

(van adj kaam$).tw. (42)

-

58

(merleau adj ponty$).tw. (192)

-

59

husserl$.tw. (225)

-

60

foucault$.tw. (734)

-

61

(corbin$ adj2 strauss$).tw. (273)

-

62

glaser$.tw. (919)

-

63

or/23-62 (1985484)

-

64

22 and 63 (523)

-

65

limit 64 to (english language and yr=“2007 -Current”) (403)

EBSCOhost CINAHL

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Sequence Analysis+”) | 12,947 |

| S2 | ((DNA or parallel or next-generation or shotgun or target∗) N1 sequenc∗) | 3,719 |

| S3 | (MPSS or NGS or CSS or TMPS) | 1,680 |

| S4 | ((high throughput N2 (analys#s or sequenc∗)) or single nucleotide polymorphism∗ or SNP or SNPs) | 8,019 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | 23,356 |

| S6 | (MH “Genetic Screening”) | 9,422 |

| S7 | ((genetic∗ or gene or genes or genome∗ or genomic∗) N2 (test or tests or testing or diagnos#s or screen∗)) | 14,387 |

| S8 | S6 OR S7 | 14,387 |

| S9 | (MH “Noninvasive Procedures”) | 1,781 |

| S10 | (noninvasive∗ or non-invasive∗) | 22,544 |

| S11 | S9 OR S10 | 22,544 |

| S12 | S8 AND S11 | 295 |

| S13 | S5 OR S12 | 23,591 |

| S14 | (MH “Prenatal Diagnosis”) | 6,278 |

| S15 | ((antenatal or ante-natal or intrauterine or intra-uterine or prenatal or pre-natal) N2 (test or tests or testing or diagnos#s or detect∗ or screen∗)) | 9,741 |

| S16 | (maternal N2 (plasm∗ or blood)) | 1,823 |

| S17 | S14 OR S15 OR S16 | 11,235 |

| S18 | S13 AND S17 | 547 |

| S19 | (((f?etal or f?etus∗ or free-f?etal or placenta∗) N2 dna) or cell-free dna) | 5,151 |

| S20 | (cff DNA or cffDNA or cf DNA or cfDNA or f DNA or fDNA or ff DNA or ffDNA) | 311 |

| S21 | ((noninvasive∗ or non-invasive∗) N5 (prenatal or pre-natal or f?etal or f?etus∗) N1 (test or tests or testing or diagnos#s or detect∗ or screen∗)) | 1,085 |

| S22 | (NIPT or NIPD or NIDT or gNIPT or NIPS) | 410 |

| S23 | S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 | 6,499 |

| S24 | (MH “Interviews+”) | 167,955 |

| S25 | MH audiorecording | 36,935 |

| S26 | MH Grounded theory | 12,160 |

| S27 | MH Qualitative Studies | 76,410 |

| S28 | MH Research, Nursing | 19,654 |

| S29 | MH Questionnaires+ | 305,524 |

| S30 | MH Focus Groups | 32,104 |

| S31 | MH Discourse Analysis | 3,572 |

| S32 | MH Content Analysis | 25,009 |

| S33 | MH Ethnographic Research | 6,166 |

| S34 | MH Ethnological Research | 5,200 |

| S35 | MH Ethnonursing Research | 180 |

| S36 | MH Constant Comparative Method | 6,388 |

| S37 | MH Qualitative Validity+ | 1,234 |

| S38 | MH Purposive Sample | 23,171 |

| S39 | MH Observational Methods+ | 18,407 |

| S40 | MH Field Studies | 2,539 |

| S41 | MH theoretical sample | 1,425 |

| S42 | MH Phenomenology | 2,624 |

| S43 | MH Phenomenological Research | 11,947 |

| S44 | MH Life Experiences+ | 25,258 |

| S45 | MH Cluster Sample+ | 3,495 |

| S46 | Ethnonursing | 258 |

| S47 | ethnograph∗ | 9,346 |

| S48 | phenomenol∗ | 17,535 |

| S49 | grounded N1 theor∗ | 14,278 |

| S50 | grounded N1 study | 1,539 |

| S51 | grounded N1 studies | 1,539 |

| S52 | grounded N1 research | 306 |

| S53 | grounded N1 analys?s | 467 |

| S54 | life stor∗ | 1,516 |

| S55 | women's stor∗ | 925 |

| S56 | emic or etic or hermeneutic∗ or heuristic∗ or semiotic∗ | 4,849 |

| S57 | data N1 saturat∗ | 434 |

| S58 | participant observ∗ | 9,712 |

| S59 | social construct∗ or postmodern∗ or post-structural∗ or post structural∗ or poststructural∗ or post modern∗ or post-modern∗ or feminis∗ or interpret∗ | 74,595 |

| S60 | action research or cooperative inquir∗ or co operative inquir∗ or co-operative inquir∗ | 7,282 |

| S61 | humanistic or existential or experiential or paradigm∗ | 27,631 |

| S62 | field N1 stud∗ | 4,551 |

| S63 | field N1 research | 1,446 |

| S64 | human science | 1,513 |

| S65 | biographical method | 56 |

| S66 | theoretical sampl∗ | 1,946 |

| S67 | purpos∗ N4 sampl∗ | 25,713 |

| S68 | focus N1 group∗ | 37,461 |

| S69 | account or accounts or unstructured or open-ended or open ended or text∗ or narrative∗ | 106,359 |

| S70 | life world or life-world or conversation analys?s or personal experience∗ or theoretical saturation | 8,542 |

| S71 | lived experience∗ | 5,213 |

| S72 | life experience∗ | 23,642 |

| S73 | cluster sampl∗ | 4,511 |

| S74 | theme∗ or thematic | 72,469 |

| S75 | observational method∗ | 18,576 |

| S76 | questionnaire∗ | 360,297 |

| S77 | content analysis | 31,142 |

| S78 | discourse∗ N3 analys?s | 4,124 |

| S79 | discurs∗ N3 analys?s | 180 |

| S80 | constant N1 comparative | 7,260 |

| S81 | constant N1 comparison | 964 |

| S82 | narrative analys?s | 2,113 |

| S83 | Heidegger∗ | 697 |

| S84 | Colaizzi∗ | 656 |

| S85 | Spiegelberg∗ | 26 |

| S86 | van N1 manen∗ | 534 |

| S87 | van N1 kaam∗ | 61 |

| S88 | merleau N1 ponty∗ | 156 |

| S89 | husserl∗ | 183 |

| S90 | Foucault∗ | 536 |

| S91 | Corbin∗ N2 strauss∗ | 267 |

| S92 | strauss∗ N2 corbin∗ | 267 |

| S93 | glaser∗ | 458 |

| S94 | S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 OR S48 OR S49 OR S50 OR S51 OR S52 OR S53 OR S54 OR S55 OR S56 OR S57 OR S58 OR S59 OR S60 OR S61 OR S62 OR S63 OR S64 OR S65 OR S66 OR S67 OR S68 OR S69 OR S70 OR S71 OR S72 OR S73 OR S74 OR S75 OR S76 OR S77 OR S78 OR S79 OR S80 OR S81 OR S82 OR S83 OR S84 OR S85 OR S86 OR S87 OR S88 OR S89 OR S90 OR S91 OR S92 OR S93 | 754,462 |

| S95 | S23 AND S94 | 705 |

| S96 | Limiters - Published Date: 20070101-20171231 Narrow by Language: - english |

584 |

Social Sciences Citation Index

| 1 | TS=((DNA OR parallel OR next-generation OR shotgun OR target∗) NEAR sequenc∗) |

| 2 | TS= (MPSS OR NGS OR CSS OR TMPS) |

| 3 | TS=((high throughput NEAR (analys?s OR sequenc∗)) OR single nucleotide polymorphism∗ OR SNP OR SNPs) |

| 4 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 |

| 5 | TS=((genetic∗ OR gene OR genes OR genome∗ OR genomic∗) NEAR (test OR tests OR testing OR diagnos?s OR screen∗)) |

| 6 | TS=(noninvasive∗ or non-invasive∗) |

| 7 | #5 AND #6 |

| 8 | #4 OR #8 |

| 9 | TS= ((antenatal OR ante-natal OR intrauterine OR intra-uterine OR prenatal OR pre-natal) NEAR (test OR tests OR testing OR diagnos?s OR detect∗ OR screen∗)) |

| 10 | TS= (maternal NEAR (plasm∗ OR blood)) |

| 11 | #9 OR #10 |

| 12 | #8 AND #11 |

| 13 | TS=(((fetal OR faetal OR fetus∗ OR faetus∗ OR free-fetal OR free-faetal OR placenta∗) NEAR dna) OR cell-free dna) |

| 14 | TS=(cff DNA OR cffDNA OR cf DNA OR cfDNA OR f DNA OR fDNA OR ff DNA OR ffDNA) |

| 15 | TS=((noninvasive∗ OR non-invasive∗) NEAR (prenatal OR fetal OR faetal OR fetus OR faetus∗) NEAR (test OR tests OR testing OR diagnos?s OR detect∗ OR screen∗)) |

| 16 | TS=(NIPT OR NIPD OR NIDT OR gNIPT OR NIPS) |

| 17 | #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 |

| 18 | TS=interview∗ |

| 19 | TS=(theme∗) |

| 20 | TS=(thematic analysis) |

| 21 | TS=qualitative |

| 22 | TS=nursing research methodology |

| 23 | TS=questionnaire |

| 24 | TS=(ethnograph∗) |

| 25 | TS= (ethnonursing) |

| 26 | TS=(ethnological research) |

| 27 | TS=(phenomenol∗) |

| 28 | TS=(grounded theor∗) OR TS=(grounded stud∗) OR TS=(grounded research) OR TS=(grounded analys?s) |

| 29 | TS=(life stor∗) OR TS=(women's stor∗) |

| 30 | TS=(emic) OR TS=(etic) OR TS=(hermeneutic) OR TS=(heuristic) OR TS=(semiotic) OR TS=(data saturat∗) OR TS=(participant observ∗) |

| 31 | TS=(social construct∗) OR TS=(postmodern∗) OR TS=(post structural∗) OR TS=(feminis∗) OR TS=(interpret∗) |

| 32 | TS=(action research) OR TS=(co-operative inquir∗) |

| 33 | TS=(humanistic) OR TS=(existential) OR TS=(experiential) OR TS=(paradigm∗) |

| 34 | TS=(field stud∗) OR TS=(field research) |

| 35 | TS=(human science) |

| 36 | TS=(biographical method∗) |

| 37 | TS=(theoretical sampl∗) |

| 38 | TS=(purposive sampl∗) |

| 39 | TS=(open-ended account∗) OR TS=(unstructured account) OR TS=(narrative∗) OR TS=(text∗) |

| 40 | TS=(life world) OR TS=(conversation analys?s) OR TS=(theoretical saturation) |

| 41 | TS=(lived experience∗) OR TS=(life experience∗) |

| 42 | TS=(cluster sampl∗) |

| 43 | TS=observational method∗ |

| 44 | TS=(content analysis) |

| 45 | TS=(constant comparative) |

| 46 | TS=(discourse analys?s) or TS =(discurs∗ analys?s) |

| 47 | TS=(narrative analys?s) |

| 48 | TS=(heidegger∗) |

| 49 | TS=(colaizzi∗) |

| 50 | TS=(spiegelberg∗) |

| 51 | TS=(van manen∗) |

| 52 | TS=(van kaam∗) |

| 53 | TS=(merleau ponty∗) |

| 54 | TS=(husserl∗) |

| 55 | TS=(foucault∗) |

| 56 | TS=(corbin∗) |

| 57 | TS=(strauss∗) |

| 58 | TS=(glaser∗) |

| 59 | #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42 OR #43 OR #44 OR #45 OR #46 OR #47 OR #48 OR #49 OR #50 OR #51 OR #52 OR #53 OR #54 OR #55 OR #56 OR #57 OR #58 |

| 60 | #17 AND #59 |

KEY MESSAGES

What Is This Qualitative Meta-Synthesis About?

Every pregnancy has the chance of carrying a chromosomal anomaly. Traditional prenatal screening uses a blood test and ultrasound to determine a fetus's risk of certain anomalies. More recently, a new screening method called noninvasive prenatal testing has been introduced. It is a blood test that checks the fetus's DNA found in the mother's blood.

At present in Ontario, noninvasive prenatal testing is publicly funded for people whose pregnancy is at high risk for a chromosomal anomaly (for example, pregnant people over age 40, or those who have had a previous pregnancy with a chromosomal anomaly). Pregnant people at average risk must pay out of pocket if they want the test.

This qualitative review looked at research that describes the beliefs, preferences, and perspectives of pregnant people, their families, clinicians, and others who have experience with noninvasive prenatal testing.

What Did This Qualitative Meta-Synthesis Find?

Most people thought noninvasive prenatal testing offered important information to pregnant people and their partners. Most were very enthusiastic about increasing access to noninvasive prenatal testing. The test can provide accurate information about chromosomal anomalies quite early in pregnancy, and it poses no physical risk to the fetus. However, many cautioned that increased access could result in the test becoming routine. This may seem like a benefit, but it could also lead to harms for pregnant people, their families, the health care system, people living with disabilities, and society as a whole.

About Health Quality Ontario

Health Quality Ontario is the provincial lead on the quality of health care. We help nurses, doctors and other health care professionals working hard on the frontlines be more effective in what they do – by providing objective advice and data, and by supporting them and government in improving health care for the people of Ontario.

We focus on making health care more effective, efficient and affordable through a legislative mandate of:

Reporting to the public, organizations, government and health care providers on how the health system is performing,

Finding the best evidence of what works, and

Translating this evidence into clinical standards; recommendations to health care professionals and funders; and tools that health care providers can easily put into practice to make improvements.

Health Quality Ontario is governed by a 12-member Board of Directors with a broad range of expertise – doctors, nurses, patients and from other segments of health care – and appointed by the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care.

In everything it does, Health Quality Ontario brings together those with first-hand experience to hear their experiences and views of how to make them better. We partner with patients, residents, families and caregivers to be full participants in designing our programs and services, to ensure they are aligned to their needs and priorities. We work collaboratively with organizations across the province to encourage the spread of innovative and proven programs to support high quality care, while also saving money and eliminating redundancy. And, we work with clinicians on the frontlines to use their collective wisdom and experience to bring about positive change in areas important to Ontario – such as addressing the challenges of hallway health care and mental health.

For example, 29 Ontario hospitals participated in a pilot program last year that reduced infections due to surgery by 18% – which in turn reduces the number of patients returning to hospital after surgery and alleviating some of the challenges faced in hallway health care. This program enabled surgeons to see their surgical data and how they perform in relation to each other and to 700 other hospitals worldwide. We then helped them identify and action improvements to care. Forty-six hospitals across Ontario are now part of this program, covering 80% of hospital surgeries.

Health Quality Ontario also develops quality standards for health conditions that demonstrate unnecessary gaps and variations in care across the province, such as in major depression or schizophrenia. Quality standards are based on the best evidence and provide recommendations to government, organizations and clinicians. They also include a guide for patients to help them ask informed questions about their care.

In addition, Health Quality Ontario's health technology assessments use evidence to assess the effectiveness and value for money of new technologies and procedures, and incorporate the views and preferences of patients, to make recommendations to government on whether they should be funded.

Each year, we also help hospitals, long-term care homes, home care and primary care organizations across the system create and report on the progress of their annual Quality Improvement Plans, which is their public commitment on their priorities to improve health care quality.

Health Quality Ontario is committed to supporting the development of a quality health care system based on six fundamental dimensions: efficient, timely, safe, effective, patient-centred and equitable.