Abstract

Objective

To review the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in older adults with depression or anxiety and comorbidities affecting functioning.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, including searches of ten databases (inception-Jul 2017).

Setting

Home/community.

Participants

People aged 60+ experiencing functional difficulties from physical or cognitive comorbidities, with symptoms or a diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety.

Interventions

Non-pharmacological interventions targeted at depression/anxiety.

Measurements

We extracted outcome data on depressive symptoms, quality of life, functioning and service use. We used random effects meta-analysis to pool study data where possible. Two authors assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.

Results

We identified 14 eligible trials including 2099 randomised participants and two subgroup analyses. Problem-solving therapy (PST) reduced short-term clinician-rated depressive symptoms (n=5 trials, mean difference in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score -4.94 (95% CI -7.90 to -1.98)) but not remission, with limited evidence for effects on functioning and quality of life. There was limited high-quality evidence for other intervention types. Collaborative care did not appear to affect depressive symptoms, functioning or quality of life; and had mixed evidence for effects upon remission. No intervention consistently affected service use, but trials were limited by small sample sizes and short follow-up periods. No anxiety interventions were identified.

Conclusion

PST may reduce depressive symptoms post-intervention in older people with depression and functional impairments. Collaborative care appears to have few effects in this population. Future research needs to assess cost-effectiveness, long-term outcomes and anxiety interventions for this population.

Prospero ID CRD42017068441

Keywords: depression, anxiety, meta-analysis, disability, medical comorbidity

Introduction

Late-life mental health is becoming an increasingly important issue. It is estimated that 37-43% of older adults have symptoms of anxiety or depression (Braam et al. 2014; Rodda et al. 2011), whilst 9-14% have a diagnosed anxiety or major depressive disorder (Wolitzky-Taylor et al. 2010; Rodda et al. 2011). Anxiety or depression in later life is associated with increased risk of cognitive decline, functional decline and increased use of healthcare services (Wolitzky-Taylor et al. 2010; Meeks et al. 2011). Frailer older adults, commonly experiencing physical or cognitive comorbidities affecting functioning (i.e. difficulties carrying out activities of daily living due to physical health conditions, in addition to depression), have a four-fold increase in the risk of clinically significant anxiety or depression (Ni Mhaolain et al. 2012). Comorbid physical and mental health disorders increases the risk of greater frailty, mortality and primary and secondary healthcare service use (Vaughan et al. 2015; Djernes et al. 2011). In an ageing population, demand for mental health services specific to later life is likely to increase.

There is an abundance of evidence assessing the effectiveness of treatments for late life depression. However, frailer older adults represent an understudied subgroup of this population, and there is evidence that physical illness, being older and impaired executive functioning can negatively impact pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment outcomes (Tunvirachaisakul et al. 2017). Antidepressants only appear to be effective when studied as a class rather than individual drug types and when reviews use an ‘older adult’ threshold of 55+ years rather than 65+ (Kok et al. 2012; Jonsson et al. 2016). Antidepressant RCTs do not account for frailty or malnutrition and the ‘oldest old’ populations are underrepresented (Benraad et al. 2016), despite greater concerns about falls and polypharmacy in these populations. Collaborative care interventions and care home interventions have some evidence of effectiveness for depression but the evidence base is very limited (Dham et al. 2017; Simning & Simons 2017). Exercise interventions for depression have not been found to be effective in those with physical comorbidities (Schuch et al. 2016). Additionally, many older adults state a preference for psychological interventions (Mohlman 2011; Gum et al. 2006).

However, secondary care services (e.g. community psychiatric services) focus mainly on severe mental illness, whilst centre-based and intensive approaches may be unsuited to community-dwelling older adults with limited mobility and frailty. CBT shows smaller effect sizes for older than younger adults and has mostly been evaluated in samples with a mean age of 60-70 in people who are otherwise healthy (R. Gould et al. 2012a; R. L. Gould et al. 2012). Existing psychological therapies offered in community settings may not fully account for issues such as increasing dependency, social isolation, reduced functional abilities and cognitive decline that are key for older people. However, some non-pharmacological therapies such as problem-solving therapy have shown promise in reducing disability, in addition to depression, in older adults with major depressive disorder and may offer promise for further research (Kirkham et al. 2016). Although some reviews have looked at frailer subgroup analyses of older adults (Jonsson et al. 2016), these have studied psychological therapies alone and documented ‘frailty indicators’ rather than clearly defining an impaired population.

Consequently, the only review with this subpopulation with impairments as its main focus appears to have been carried out two decades previously (Landreville & Gervais 1997). We therefore aimed to review the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to reduce depression and anxiety in older adults with comorbidities affecting functioning.

Methods

We systematically reviewed Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) (Prospero registration CRD42017068441).

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We developed a comprehensive search strategy (see Appendix A1) with terms based on age, impairments, depression/anxiety and study type. We searched the following databases (inception-July 2017): MEDLINE, MEDLINE in Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, AMED, Web of Science - Social Science Citation Index, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials & NHS Health Economic Evaluation Database, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Sociological Abstracts, Social Care Online and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts.

We performed additional searches of clinicaltrials.gov, UK Clinical Trials Gateway and World Health Organisation International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (inception-Sep 2017) to identify ongoing studies. We screened the reference lists of included studies/relevant systematic reviews and used forward citation tracking of all included studies. We used author searches to follow up conference abstracts, trials register entries and protocols where available and necessary.

Our inclusion criteria were as follows:

Participants: older adults (aged 60+ years); functional difficulties (including difficulties in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental ADLs (IADLs), housebound, frail, low functioning scores on a validated scale, recipient of relevant support services (e.g. social care services)); symptoms/diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety

Interventions: Home- or community-based interventions; delivered by any health, social, lay or voluntary provider; single or multicomponent intervention aimed primarily at addressing depression or anxiety

Comparator: any

Outcomes: Depressive and anxiety symptoms using validated questionnaires, other depression or anxiety outcomes (e.g. recovery), wellbeing, quality of life, functioning, service use

Study type: parallel-group, cluster or crossover randomised controlled trials, economic evaluations of RCTs

We lowered our original age inclusion criterion from 75+ to 60+ years as this allowed inclusion of a number of additional relevant studies of functionally impaired older adults with mean ages between 60 and 75.

We excluded interventions targeted at caregivers or targeted at specific health conditions (e.g. dementia, arthritis) in order to be generalizable to the wider frailer population, people described as generically ‘at risk’ or ‘multimorbid’ (unless there was documented associated difficulties in functioning); care home interventions (recently reviewed by Simning & Simons (2017)); studies in which participants were not experiencing at least mild depression/anxiety; inpatient interventions; medication-only interventions (interventions containing a medication component were included); interventions focussed primarily on another issue (e.g. frailty, falls prevention) in which depression/anxiety is a secondary target as it would be difficult to be sure of the effective components; reviews, qualitative studies, quasi-experimental and uncontrolled studies.

RF screened titles and abstracts and YB independently checked 10% of these. We took an inclusive approach and screened the full texts of all studies assessing interventions in samples of depressed or anxious general older adults, as we anticipated that difficulties in functioning may not be clearly reported in the abstract. RF and YB independently screened 10% of the full texts to ensure consistency in applying the inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved through discussion, then each screened 50% of the remaining full texts. Dual review was undertaken for a further 7% of studies where there was uncertainty, with input from KW where needed. We contacted five authors for further data to inform inclusion and three replied. We sought further data regarding ten included studies from nine authors and eight replied, six of whom were able to provide further data.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted data on participants, study type, intervention description (according to the TIDIER checklist (Hoffmann et al. 2014)), outcomes assessed and main findings. If a study had multiple publications, we considered the main results paper as the primary paper and included information from related papers (e.g. protocols) where relevant. RF and YB independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins et al. 2011) and resolved disagreements through discussion. Overall ratings were judged on least score counts, however as non-pharmacological therapies are often compared to usual care and a placebo control is not always desirable or practical, we did not include participant blinding in the overall trial rating. Within ‘other bias’ we assessed whether studies documented or controlled for use of antidepressants. Risk of bias ratings informed our narrative synthesis. We intended to assess publication bias using funnel plots but had insufficient data for this (Sterne et al. 2011).

Synthesis

We grouped studies according to intervention type: problem-solving therapy, other psychological therapies and collaborative care (defined as complex interventions involving a multi-professional approach to care, a structured management plan, scheduled follow ups and enhanced interprofessional communication (Archer et al. 2012)). We conducted meta-analysis of similar outcomes post-intervention, the most relevant and widely available timepoint (follow-up timepoint meta-analysis was precluded by differing outcome types and timepoints). Self-reported and clinician-rated outcomes were not combined as these produced different effect estimates in a previous meta-analysis (Cuijpers et al. 2010). We summarised effects for continuous data using mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) where appropriate with weighting by inverse variance (Higgins & Green 2011). For dichotomous data, we combined effects using odds ratios, weighted by the Mantel-Haenszel method (Higgins & Green 2011). All analyses used a random effects model as we anticipated high clinical heterogeneity, quantified using the I2 statistic. Similar interventions within a single trial were aggregated into one intervention group for meta-analysis using Higgins & Green’s (2011) formulae. Where necessary, we used p values and test statistics to compute SDs, standardised mean difference and 95% confidence intervals then combined studies using the generic inverse variance method (Higgins & Green 2011).

RF performed meta-analysis using Revman 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2014). YB checked all data used in meta-analysis with the original papers or authors communications and independently verified calculations (e.g. calculation of standard deviations from p values). We summarised all other outcomes, including longer term follow up timepoints, narratively.

Results

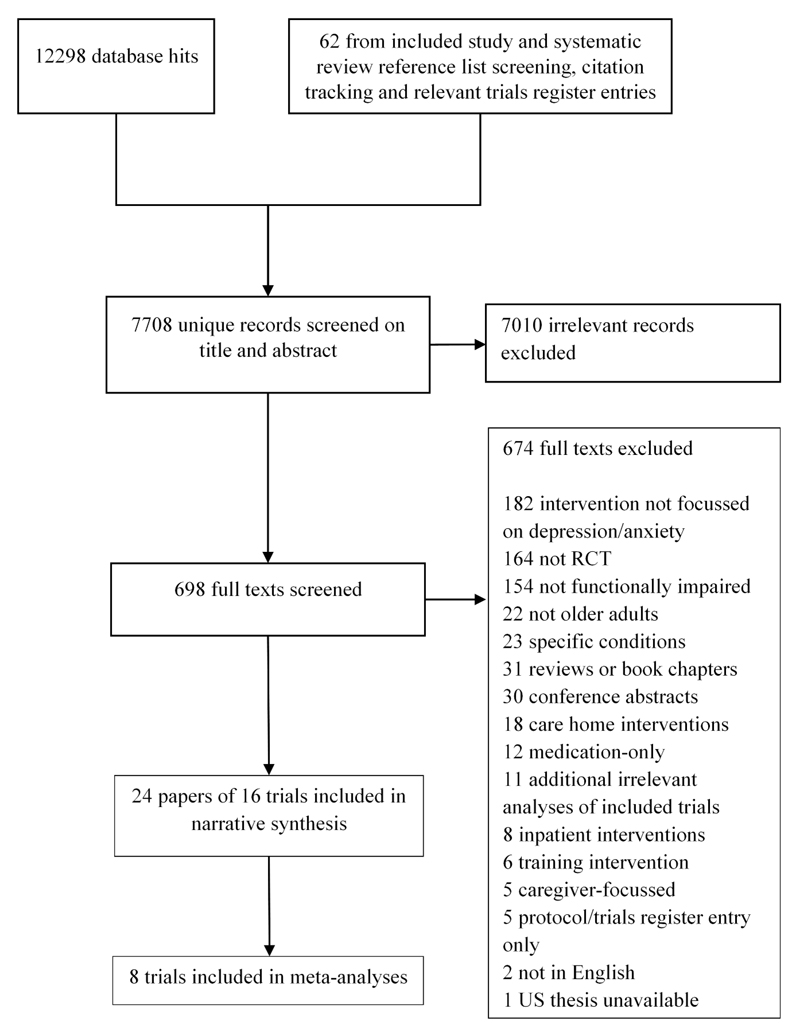

We identified 7708 unique references and screened 698 full texts (see Figure 1). Full texts were largely excluded due to not targeting depression/anxiety (in participants or intervention (n=181), study type (n=164) or not targeting an impaired older population (n=154). We found five relevant ongoing trials as protocols or trials register entries that had not previously been located (findings not currently reported, summarised in Appendix A3).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of studies included in the review.

Description of included studies

We included 14 trials with a total of n=2099 randomised participants, comprising 11 RCTs (Kiosses et al. 2010; Kiosses et al. 2015; Alexopoulos et al. 2016; Ell et al. 2007; Banerjee et al. 1996; Enguidanos et al. 2005; Serrano et al. 2004; Gellis et al. 2008; Nyunt 2010; Ciechanowski et al. 2004; Choi et al. 2014), one cluster RCT (Bruce et al. 2015), one pilot RCT (Gellis et al. 2007) and one RCT with a non-concurrent control group (Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999) (see Appendix A2 for a detailed summary of study characteristics). We also included two RCT subgroup analyses (Blanchard et al. 1995; Landreville & Bissonnette 1997) (one n not reported, one n=23 randomised). Most studies were carried out in the US (n=10), with two UK studies (Blanchard et al. 1995; Banerjee et al. 1996) and one each in Australia (Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999), Singapore (Nyunt 2010), Spain (Serrano et al. 2004) and Canada (Landreville & Bissonnette 1997). Sample sizes varied from 23 to 311.

Participant mean ages ranged from 64.8 to 84.9 years, with higher proportions of women in all trials (range from 69.6% to 87.5%). Many studies captured a diverse population, including substantial proportions of ethnic minorities in studies reporting this data (see Table 1). Four studies focussed on or included a considerable proportion of those with low incomes (Alexopoulos et al. 2016; Choi et al. 2014; Landreville & Bissonnette 1997; Bruce et al. 2015) and a range of educational levels were reported. Many studies used a screening instrument to define depression criteria, with or without the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants in each study.

| Study ID | Depression severity (criteria) | Criteria for physical impairments affecting functioning | Education (mean (SD) years or %level) | Ethnicity | Cognition inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PST | |||||

| Alexopoulos 2016 | Major (SCID + SI) | Receiving support services, IADL impairments | 13.2 (2.9) yrs | Not reported | ≥24 (MMSE) + no dementia diagnosis |

| Choi 2014 | Major (SI) | Homebound (Medicare criteria), receiving support services | <high school 7.6%, high school 19.6%, some college 33.5%, college degree 13.9%, graduate school 9.5% | Non-Hispanic White 42.4%, African American/Black 32.9%, Hispanic 24.7% | No dementia diagnosis |

| Ciechanowski 2004 | Minor (SCID) | Receiving support services | Beyond high school 58% | African American 36%, Asian American 4%, Hispanic 1%, American Indian 1% | <3 (6 item MMSE) |

| Gellis 2007 | Major (SI) | Home care patients | 11.9 yrs (SD not reported) | White 80%, Black 10%, Hispanic 10% | ≥24 (MMSE) |

| Gellis 2008 | Major (SCID + SI) | Home care patients | Int 11.2 yrs Control 11.34 yrs (SDs not reported) |

Int Caucasian 85%, African American 5%, Hispanic 10% Control Caucasian 85%, African American 5% Hispanic 10% | ≥25 (MMSE) |

| Kiosses 2010 | Major (SCID + SI) | IADL impairments, mobility impairment | Int 12.50 (3.67) yrs Control 12.23 (2.68) yrs |

Caucasian 73.33%, African American 26.67% | ≥19 (MMSE) plus ≤30 (DRS IP) or ≤18 (Stroop CW) |

| Kiosses 2015 | Major (SCID + SI) | IADL impairments, mobility impairment | Int 12.86 (3.37) yrs Control 13.35 (2.72) yrs |

Int White 81.08%, African American 18.92%, Hispanic 8.11% Control White 83.78%, African American 16.22%, Hispanic 0% |

≥17 (MMSE) |

| Collaborative care | |||||

| Banerjee 1996 | Major (SI) | Home care patients | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Blanchard 1995 | Mixed (SI) | Mobility impairment | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Bruce 2015 | Mixed (SI) | Home care patients | 12.0 (3.5) yrs | White 80.7%, Black 18.0%, Other 1.3% | No dementia diagnosis |

| Ell 2007 | Mixed (SI) | Home care patients | Not reported | Int Non-Hispanic White 75%, Control Non-Hispanic White 69% | Cognitive impairment precluding consent |

| Enguidanos 2005 | Mixed (SI) | ADL impairments | <high school 40%, high school 33%, some college 27% | White 66%, African American 17%, Latino 13%, Asian 4%, Native American 1.3% | ≤4 (SPMSQ) |

| Llewellyn-Jones 1999 | Mixed (SI) | Residing in supported living | Not reported | Not reported | ≥18 (MMSE) |

| Nyunt 2010 | Minor (SI) | Receiving support services, residing in supported living | 50.9% (UC) and 46.1% (CC) were illiterate | Int Chinese 84.3% Control Chinese 85.7% |

No dementia diagnosis |

| Bibliotherapy | |||||

| Landreville 1997 | Mixed (SI) | ADL or IADL impairments, mobility impairment | Int 7.80 yrs Control 8.53 yrs (SDs not reported) |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Life review therapy | |||||

| Serrano 2004 | Mixed (SI) | Receiving support services | Literate 7%, elementary school 67.4%, secondary school 23.3%, university 2.3% | Not reported | ≥28 (MMSE) |

ADL = Activities of Daily Living, DRS IP=Dementia Rating Scale Initiation/Preservation subscale, IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination, N = number, NR = not reported, QoL = Quality of Life, RCT = Randomised Control Trial, SI=screening instrument, SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, SPMSQ=Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, Stroop CW=Stroop Colour-Word test

The majority of studies excluded people below a certain cognition threshold (n=8) or those with dementia (n=3) (see Table 1). Consequently, many studies, even if using a lower cognition threshold, reported mean baseline cognition scores within a normal range (i.e. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores between 26.8 and 29.3 across studies (Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999; Alexopoulos et al. 2016; Bruce et al. 2015), 1.58 on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Enguidanos et al. 2005) and 5.5 on the 6-item MMSE (Ciechanowski et al. 2004)). Only two studies included people with greater cognitive impairment (Kiosses et al. 2015) or executive dysfunction (Kiosses et al. 2010) resulting in a wider range of cognition scores, but still normal mean cognitive function in Kiosses et al (2010). Two studies did not report any cognition data (Blanchard et al. 1995; Banerjee et al. 1996).

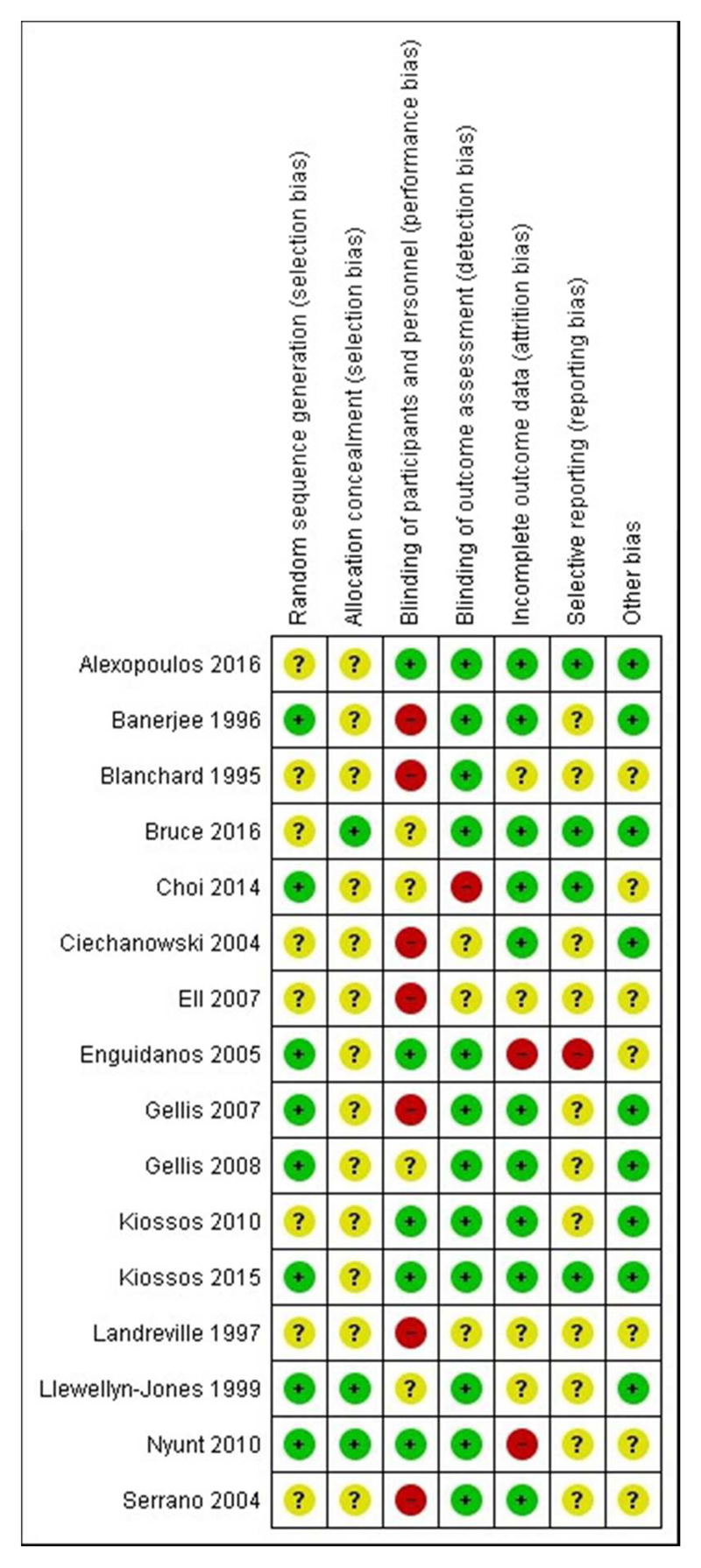

Risk of bias in included studies

Most studies were at overall unclear risk of bias (see Figure 2), largely due to limited reporting of random sequence generation (n=8) and allocation concealment (n=13) and lack of an online or published protocol to assess selective reporting (n=11). Studies were most commonly at low risk of bias for outcome assessment (n=12), incomplete outcome data (n=10) and reporting or controlling for antidepressant use (other bias, n=9). Studies were most commonly at high risk of bias for participant blinding (n=7), although this was expected as blinding participants can be difficult in trials of complex interventions and so was not included in the overall score. Individual risk of bias ratings are discussed throughout the synthesis for each outcome.

Figure 2. Risk of bias in included studies.

Modified problem-solving therapy (n=7 trials, including n=688 randomised participants)

Problem-solving therapy (PST) aims to systematically identify and address daily life problems to reduce depression and improve future coping skills (Ciechanowski et al. 2004), through standard steps including: identifying problems, establishing achievable goals, brainstorming solutions, using decision-making guidelines, evaluating and contrasting solutions, developing action plans and evaluating outcomes. PST was modified in some studies to suit a more impaired population:

Integration into existing home care services, with six sessions to fit home care’s fast pace and limited resources and individuals’ frailty (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008)

Emphasising social activation, increasing outdoor interactions and developing an exercise programme (Ciechanowski et al. 2004)

Problem Adaptation Therapy: Including environmental adaptations to circumvent behavioural and/or functional limitations and involving willing/available caregivers over 12 weeks (Kiosses et al. 2010; Kiosses et al. 2015)

Delivery over videoconferencing software (tele-PST) to enable home-based therapy (Choi et al. 2014)

Increasing pleasant events (Gellis et al. 2007; Ciechanowski et al. 2004; Kiosses et al. 2010; Gellis et al. 2008; Choi et al. 2014)

PST was most commonly delivered by social workers (usually Masters-level) (Alexopoulos et al. 2016; Gellis et al. 2007; Ciechanowski et al. 2004; Kiosses et al. 2010; Choi et al. 2014), registered nurses (Ciechanowski et al. 2004) or clinical psychologists and clinical doctorate candidates (Kiosses et al. 2015). All delivered PST face-to-face at participants’ homes over 6-12 sessions, apart from one trial comparing delivery over skype to face-to-face and to care calls (Choi et al. 2014) (collapsed to a single PST group for meta-analysis as per Higgins & Green (2011)). Other trial comparators included usual care (Ciechanowski et al. 2004), enhanced usual care e.g. with basic education (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008) or attention controls e.g. supportive therapy (Kiosses et al. 2010; Kiosses et al. 2015). One compared case management plus PST to case management alone (Alexopoulos et al. 2016).

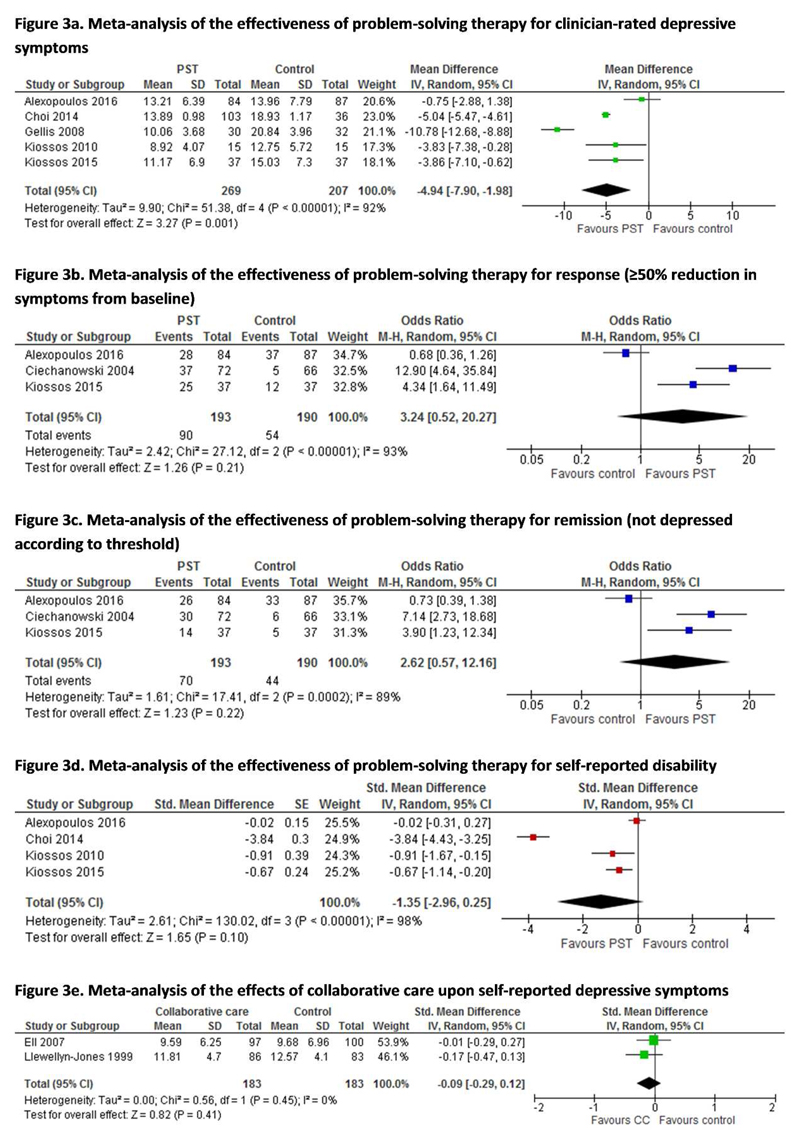

Depressive symptoms

Modified PST significantly reduced clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) scores post-intervention (see Figure 3a, n=5, MD -4.94 (95% CI -7.90 to -1.98), p=0.001). Two further studies found significantly lower scores on other measures, including the Montgomery-Asberg Depression rating Scale (MADRS) compared to supportive therapy (Kiosses et al. 2015) and 20-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale (HCSL-20) compared to usual care (Ciechanowski et al. 2004). Reduced depressive symptoms were maintained 6-12 months from baseline in studies assessing this (Choi et al. 2014; Gellis et al. 2008; Alexopoulos et al. 2016; Ciechanowski et al. 2004). All studies were at overall unclear risk of bias (with some low-risk domains), apart from Choi, Marti et al. (2014), who used non-blinded outcome assessors. PST did not however significantly increase the post-intervention clinician-rated odds of response (≥50% symptom reduction from baseline, OR 3.24 (95% CI 0.52 to 20.27), Figure 3b) or remission (OR 2.62 (95%CI 0.57 to 12.16), Figure 3c) using the HAM-D (Alexopoulos et al. 2016), HSCL-20 (Ciechanowski et al. 2004) and MADRS (Kiosses et al. 2015). Similarly, no effects were found 12 weeks post-intervention (Alexopoulos et al. 2016) or at 36-week (Choi et al. 2014) or 12 month follow-up (Ciechanowski et al. 2004). Kiosses et al. 2015 did not assess longer term outcomes.

Figure 3. Forest plots of meta-analyses.

We could not meta-analyse self-reported depressive symptoms, as two papers reported identical mean and SD 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) scores at all timepoints, suggesting a reporting error (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008). These figures did however indicate significantly lower symptoms at post-intervention, 3 months and 6 months (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008). One also found significantly lower Beck Depression Inventory scores post-intervention (PST vs usual care, 10.20 vs 27.4, p<0.001), maintained at 6 months (Gellis et al. 2007).

Functioning and disability

PST did not significantly reduce self-reported disability post-intervention (Figure 3d, n=4, SMD -1.35 (95% CI -2.96 to 0.25), p=0.10) when assessed using the World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule and the Sheehan Disability Scale. Within one study, significant effects upon disability were maintained at 24 weeks for tele-PST and face-to-face PST and at 36 weeks for tele-PST (Choi et al. 2014). Another study, similarly to post-intervention, found no effects at 12 weeks follow up (Alexopoulos et al. 2016).

Quality of life

Evidence about the impact of PST upon quality of life was mixed across two studies using the Quality of Life Inventory. Meta-analysis was not undertaken as the SDs (but not means) reported were identical in both papers at all timepoints (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008), suggesting a potential reporting error. Significantly higher quality of life was found post-intervention and at 3 and 6 months in Gellis et al. (2007) but no effects were found in Gellis et al. (2008). Within Ciechanowski et al (2004) there were improvements in emotional and functional but not social or physical wellbeing over 12 months on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale – General.

Service use and costs

None of the three studies reporting service use found PST to significantly affect primary, secondary or home care service use over the treatment period or longer follow up, although this was considered beneficial where PST was delivered as part of home care (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008; Ciechanowski et al. 2004). One study reported intervention costs ($630 per patient) (Ciechanowski et al. 2004) and two noted that social work home visits were reimbursable by Medicare (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008). No other studies reported this data.

Collaborative care interventions (n=7 studies including n=1351 participants)

Seven studies evaluated collaborative care interventions, provided in the community or in care services (components listed in Table 2). Key intervention providers were usually nurses (Nyunt 2010; Blanchard et al. 1995; Bruce et al. 2015; Ell et al. 2007), but could include social workers or psychologists (Ell et al. 2007) or medical staff (Banerjee et al. 1996).

Table 2. Collaborative care intervention content.

| Intervention component | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff | Patient | ||||||||||

| Study | Location | Specific depression case manager* identified | Monitoring | MDT team meetings | Provider education | Enhanced coordination/communication between providers | MDT management plans | Patient education | Psychotherapy offered | Prescription/management of antidepressants | Other (e.g. social activities offered) |

| Banerjee 199629 | Community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Blanchard 199539 | Community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Bruce 201536 | Home care services | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (goal setting only) |

✓ | ||||

| Ell 200739 | Home care services | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Enguidanos 200539 | Geriatric care management services | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Llewellyn-Jones 199939 | Assisted living and hostel facilities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Nyunt 201039 | Community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

aka key worker, case worker, Clinical Depression Specialist etc

MDT=multidisciplinary team

Baseline depressive symptoms levels were mainly mixed (Enguidanos et al. 2005; Blanchard et al. 1995; Bruce et al. 2015; Ell et al. 2007), with two studies focussing on major depression (Banerjee et al. 1996; Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999) and one on minor depression (Nyunt 2010). Comparators included “routine care” (further details not reported) (Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999); GP management with or without notification of depression severity (Nyunt 2010; Blanchard et al. 1995; Banerjee et al. 1996; Ell et al. 2007); usual geriatric case management with care plan (Enguidanos et al. 2005); and usual care enhanced by screening, notifying GPs (Ell et al. 2007) or following agency procedures (Bruce et al. 2015) if the patient did not improve.

Potential meta-analyses for collaborative care interventions relied mainly on data from an unpublished thesis, Nyunt (2010), whose analysis was at high risk of bias as they did not use an intention-to-treat analysis. We therefore only undertook meta-analysis where higher quality data were available (self-reported depressive symptoms).

Effects upon depressive symptoms (n=7)

There were mixed effects on continuous depressive symptom scores. Two large studies found no effects on clinician-rated HAM-D scores post-intervention or at 12 months (Nyunt 2010; Bruce et al. 2015). A subgroup with major depression and one smaller study (n=69) found significant reductions in depressive symptoms (Banerjee et al. 1996; Bruce et al. 2015), whilst Blanchard et al’s (1995) subgroup analysis found greater symptom improvements in those with physical capacity than those without, although this did not interact with treatment group. There were similarly no effects upon post-intervention self-reported depressive symptoms (n=2, SMD -0.09 (95%CI -0.29 to 0.12), p=0.41, Figure 3e). A further unpublished study (at high risk of bias due to higher intervention arm dropout rates) found no differences in 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scores post-intervention or at 12 months (Enguidanos et al. 2005). Nyunt (2010) (at high risk of bias) found some differences in GDS and BDI scores post-intervention but not at 12 months.

Odds of depression remission were mixed. Banerjee et al (1996) found significant higher odds of clinician-rated remission using Geriatric Mental State AGECAT categories, whilst Nyunt (2010) found no differences in remission using HAM-D at any timepoint. Odds of self-reported remission was significantly higher using the GDS-15 (Nyunt 2010) with significant positive movement into ‘less depressed’ categories using the GDS-30 cutoffs (Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999); but not using the BDI (Nyunt 2010) or in the odds of response using the PHQ-9 at 4, 8 or 12 months (Ell et al. 2007).

Functioning (n=2)

There was no evidence that collaborative care affected 12-item short form (SF-12) physical functioning subscale scores, Mahoney & Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scores, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scores (Nyunt 2010) or SF-20 scores (Ell et al. 2007) at any timepoint up to 12 months.

Quality of Life (n=2)

Mental functioning scores (SF-12) were significantly higher post-intervention in the collaborative care group compared to usual care, but not at 12 months in Nyunt (2010), and Ell et al. (2007) found no differences in odds of an improvement in mental, social or role functioning scores.

Service use and costs (n=5)

One study found significant effects for collaborative care on number of days in hospital (3.59 vs 6.31, p=0.04, unpublished data supplied by authors) (Enguidanos et al. 2005). However one large cluster trial found no significant reductions in risk of 30- or 60-day hospitalisation from home health services (except when including service-level data from all people in all clusters, rather than those agreeing to full study participation) (Bruce et al. 2016). Others similarly found no differences in 12 month odds of hospitalisation (meta-analysis not possible due to insufficient data) (Nyunt 2010; Ell et al. 2007), home care visits (Enguidanos et al. 2005; Ell et al. 2007), primary care or physician visits (Nyunt 2010; Enguidanos et al. 2005), home care readmissions (Ell et al. 2007), moves to long term care (Enguidanos et al. 2005) or emergency department visits (Enguidanos et al. 2005; Ell et al. 2007; Llewellyn-Jones et al. 1999). Only Enguidanos et al (2005) calculated healthcare costs (unpublished), which were significantly lower at four ($3295 vs 5417, p=0.04) and 12 months ($8403 vs $11,242, p=0.05). Banerjee et al. (1996) reported extra costs of a half time doctor as a depression case manager but did not cost this.

Other psychological therapies

The evidence base available for other psychological therapies in this population consisted of small single studies at unclear risk of bias. Four sessions of life review therapy focussed on different life periods had significant post-intervention effects on self-reported depressive symptoms (20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale) and life satisfaction (Life Satisfaction Index A) compared to social visits in 50 social care services clients (Serrano et al. 2004). Bibliotherapy (i.e. reading a CBT-based book Feeling Good over 4 weeks) reduced depressive symptoms in two out of three scales (BDI, GDS-30, Inventory to Diagnose Depression) compared to weekly supportive phone calls in a subgroup analysis of 23 people with disability in at ≥1 ADL, IADL or mobility, with no effect upon functioning (Landreville & Bissonnette 1997). Neither study reported service use or cost data.

Discussion

Within this review, we included 14 RCTs including 2099 randomised individuals, plus two subgroup analyses, primarily assessing modified problem-solving therapy (n=7) and collaborative care interventions (n=7). For older adults with depression and physical comorbidities affecting functioning, we found that home-based problem-solving therapy significantly reduced depressive symptoms, but did not affect remission, functioning or service use and showed mixed effects on quality of life. The evidence for collaborative care was heterogeneous, with no effects on depressive symptoms in meta-analysis and narrative synthesis showed little effect upon quality of life, service use or functioning, and mixed effects upon remission. The evidence base for bibliotherapy and life review was too limited to draw conclusions. No treatments for anxiety were identified in this population.

Similar effect sizes for PST on depressive symptoms have been noted in the general older adult population (Kirkham et al. 2016; Jonsson et al. 2016). However Kirkham et al (2016) also found effects on disability. We included a greater number of trials than Kirkham et al, however outcomes appeared to be broadly consistent between different measures used. It is therefore likely that either trials were underpowered to detect differences (as functioning was never a primary outcome) or the results were mainly affected by a single study, in which both study arms also received case management (Alexopoulos et al. 2016). The latter study may also be the reason for the lack of effect on remission despite a strong effect on symptoms, or may be due to the high baseline depressive symptom scores (e.g. HAM-D scores of 21-24). Heterogeneity was also very high (≥90%) for some PST outcomes, which could relate to differences in timepoints (e.g. immediately post-intervention or some weeks after) or intervention components. There were too few studies reporting quality of life outcomes to draw firm conclusions, and quality of life appears to get little attention in trials assessing late life depression treatments (Jonsson et al. 2016; Kirkham et al. 2016). Whilst a few larger studies have shown positive effects upon late life depression for primary care-based collaborative care in general older adult populations, smaller studies in other settings indicate mixed effects (Dham et al. 2017) similarly to our review, although individual patient data meta-analyses have reported similar collaborative care effects regardless of the number or type of chronic physical conditions across all ages (Panagioti et al. 2016).

Although executive dysfunction has been linked to worse treatment outcomes (Tunvirachaisakul et al. 2017), the two studies including participants with a wider range of cognition scores (Kiosses et al. 2010; Kiosses et al. 2015) found results consistent with those restricted to normal scores, suggesting that problem solving therapy may be equally effective in a cognitively impaired population. Mixed reporting of cognition and mixed results in collaborative care studies mean that conclusions cannot be drawn for these interventions.

Strengths and limitations of the evidence base

The evidence base was largely at unclear risk of bias due to poor reporting. Studies at high risk of bias were rare, apart from a few key collaborative care trials. Regarding generalisability, included studies recruited ethnically and socioeconomically diverse participants, although most were carried out in the US and all had a higher proportion of female participants. Although within most studies participants fell within a ‘normal’ cognition range, some studies included people with a range of cognition levels that included those with cognitive impairment. PST appears to have consistent effects on depression in studies with participants within this review with greater cognitive impairment (Kiosses et al. 2010; Kiosses et al. 2015), and those with executive dysfunction but no physical disability (Alexopoulos et al. 2003; Areán et al. 2010).

Post-intervention effectiveness was well-documented, however follow-up periods of over one year were rare. Previous research suggests that depression is associated with faster physical decline and greater health service use (Vaughan et al. 2015; Djernes et al. 2011). Reducing depression may maintain physical functioning rather than improve it, which may only be apparent in larger samples over longer follow up. Quality of life information was limited, whilst adverse event data were omitted by all but two studies (Kiosses et al. 2015; Banerjee et al. 1996). We found no trials of CBT or any therapies for anxiety targeted to our population. Attrition in many studies was similar across control and treatment arms, suggesting that dropout was not an issue likely to affect review results. However, collaborative care studies had mixed fidelity and adherence in those measuring it, which may be areas of or heterogeneity in outcomes (e.g. in Ell et al (2007) 30% received no intervention care). Within PST, generally high fidelity scores were reported, and where assessed, participant attendance was fairly high, even for studies with greater numbers of sessions. Book-based CBT had very low adherence (on average only half of the book was read (Landreville & Bissonnette 1997)).

Strengths and limitations of the review

We searched a wide range of databases using comprehensive search terms, and additional methods located only one extra subgroup analysis and one small study. One reviewer assessed titles, abstracts and full texts. However, they took an inclusive approach and a proportion were screened independently by a second reviewer with good agreement. We did not include trials of interventions for depression in older people as a general population. Although these may include some participants with difficulties in functioning arising from physical comorbidities, these are only likely to be a small proportion as the mean age within many of these trials is 65-70 (R. Gould et al. 2012b; R. Gould et al. 2012a). However, we took an inclusive approach to screening to identify larger trials that included a subgroup analysis in a frailer population. Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias and extracted meta-analysis data. Meta-analysis was limited by inconsistencies in outcome timepoints (e.g. immediately post-intervention to six weeks after), differing intervention lengths and poor study quality. We received a good response from author requests for further data.

Implications for practice

Currently, UK psychological therapy services commonly focus primarily on delivering CBT for depression and anxiety, with low referral to and uptake of these services in older people (Walters et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2005). In our review we found no evidence regarding the use of CBT in older people with physical comorbidities affecting functioning. It may be that CBT is more cognitively demanding than other therapies and so has not been trialled in those who are frailer and more likely to have mild cognitive impairment. Although there is some evidence for its effectiveness in the general older adult population, effect sizes are smaller than for younger people (R. Gould et al. 2012a; R. Gould et al. 2012b), and frailer people may find CBT difficult or even detrimental to apply when their problems or negative thoughts may be realistic and valid (Isaacowitz & Seligman 2002).

Home-based problem-solving therapy, delivered by non-mental health specialists in perhaps as few as six sessions, may be effective in this population with moderate-severe depressive symptoms at least short-term, and should be considered in practice. The effect size is slightly higher for modified PST (1.79 (3.39, 0.20), converting the MD from Figure 3a to SMD) than that reported for SSRIs in general older adult populations (SMD 1.2 (0.3-2.1)) (Kok et al. 2012). PST also has a high level of acceptability (Gellis et al. 2007; Gellis et al. 2008; Kiosses et al. 2010; Kiosses et al. 2015) and may address the importance placed by older people with complex problems upon feeling a sense of mastery about solving issues and helping a combination of issues that older people with complex problems attribute depression to (Von Faber et al. 2016). Provision of this alternative therapy in routine care may support increasing the access to mental health support for frail older people. The evidence for collaborative care is more conflicting and insufficient to make recommendations. Bibliotherapy and ‘life review’ (a therapy including the recall, evaluation and integration of life experiences to achieve a positive sense of self in the later stages of life) (Lan et al. 2017) lacked sufficient evidence to make recommendations for this group.

Implications for research

PST showed positive short-term effects for reducing depressive symptoms, although did not show effects upon other outcomes. Large scale RCTs therefore need to be powered to assess the effects of PST upon a more comprehensive set of outcomes that are relevant to older people, particularly functioning (a key frailty outcome) (Ferrucci et al. 2004) and quality of life (Lenze et al. 2016), and especially in the long term. Evaluation of hospitalisations, social care use and cost-effectiveness is also vital to assist commissioning decisions, as home-based services are potentially costly but may deliver long term cost-savings in health or social care use. Other non-pharmacological interventions for depression that have shown to be effective in general older adult populations, such as CBT, behavioural activation and life review (R. Gould et al. 2012a; R. Gould et al. 2012b; Lan et al. 2017; Orgeta et al. 2017), may also offer promise, but could be optimised through working with frail older people to understand how these treatments could be better tailored to their needs and abilities. Book-based CBT had low adherence in this population and exercise interventions do not appear to be effective when people have a medical comorbidity (Schuch et al. 2016), so these may be a less useful avenues for investigation. Research into interventions for anxiety (and comorbid anxiety and depression, which negatively impact upon late life depression treatment outcomes (Tunvirachaisakul et al. 2017)) in this population is also needed, as the evidence base for older adults tends to focus on depression to the detriment of other psychiatric disorders (Dham et al. 2017).

Conclusions

Home-based problem-solving therapy may significantly reduce depressive symptoms in older adults with physical comorbidities affecting functioning in the short term. The evidence for collaborative care is mixed in this population, and effects on functioning, quality of life and service use are currently unknown. Other therapies and therapies for anxiety lack an evidence base in this population and require further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors who kindly responded to our requests for further data.

RF was funded by the National Institute of Health Research School for Primary Care Research. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Description of authors’ roles

RF and KW designed the review protocol. RF ran the searches, screened references, assessed risk of bias, conducted meta-analysis and drafted the manuscript. YB conducted trials register searches, screened references, assessed risk of bias and provided feedback on manuscript drafts. KW provided feedback throughout the review process, was a third reviewer for resolving any inclusion disagreements and provided feedback on manuscript drafts. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Alexopoulos GS, et al. Clinical Case Management versus Case Management with Problem-Solving Therapy in Low-Income, Disabled Elders with Major Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(1):50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Areán P. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2003;11(1):46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems (Review) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(10):CD006525. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areán PA, et al. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1391–1398. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of effect of intervention by psychogeriatric team on depression in frail elderly people at home. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 1996;313:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benraad CEM, et al. Geriatric characteristics in randomised controlled trials on antidepressant drugs for older adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;31(9):990–1003. doi: 10.1002/gps.4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard MR, Waterreus A, Mann AH. The effect of primary care nurse intervention upon older people screened as depressed. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 1995;10(4):289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Braam AW, et al. Depression, subthreshold depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms in older Europeans: Results from the EURODEP concerted action. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;155(1):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: the Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(1):55–64. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, et al. Integrating Depression Care Management into Medicare Home Health Reduces Risk of 30- and 60-Day Hospitalization: The Depression Care for Patients at Home Cluster-Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(11):2196–2203. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, et al. Six-month postintervention depression and disability outcomes of in-home telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults. Depression and anxiety. 2014;31(8):653–661. doi: 10.1002/da.22242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski P, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(13):1569–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, et al. Self-reported versus clinician-rated symptoms of depression as outcome measures in psychotherapy research on depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(6):768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dham P, et al. Collaborative Care for Psychiatric Disorders in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;62(11):761–771. doi: 10.1177/0706743717720869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djernes JK, et al. 13 Year Follow Up of Morbidity, Mortality and Use of Health Services Among Elderly Depressed Patients and General Elderly Populations. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 2011;45(8):654–62. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.589368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, et al. Managing depression in home health care: a randomized clinical trial. Home health care services quarterly. 2007;26(3):81–104. doi: 10.1300/J027v26n03_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enguidanos SM, Davis C, Katz L. Shifting the Paradigm in Geriatric Care Management: Moving from the medical model to patient-centred care. Social Work in Health Care. 2005;41(1):1–16. doi: 10.1300/J010v41n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Faber M, et al. Older people coping with low mood: A qualitative study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28(4):603–612. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215002264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, et al. Designing Randomized, Controlled Trials Aimed at Preventing or Delaying Functional Decline and Disability in Frail, Older Persons: A Consensus Report. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(4):625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis ZD, et al. Problem-solving therapy for late-life depression in home care: a randomized field trial. American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2007;15(11):968–978. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180cc2bd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis ZD, et al. Randomized controlled trial of problem-solving therapy for minor depression in home care. Research on Social Work Practice. 2008;18(6):596–606. [Google Scholar]

- Gould R, Coulson M, Howard R. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012a;60(10):1817–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould R, Coulson M, Howard R. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012b;60(2):218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RL, Coulson MC, Howard RJ. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety Disorders in Older People: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(2):218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gum A, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(1):14–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TC, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2014 Mar;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Seligman MEP. Cognitive style predictors of affect change in older adults. International journal of aging & human development. 2002;54(3):233–253. doi: 10.2190/J6E5-NP5K-2UC4-2F8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson U, et al. Psychological treatment of depression in people aged 65 years and over: A systematic review of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0160859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, et al. Home-delivered problem adaptation therapy (PATH) for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders: a preliminary study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18(11):988–998. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6947d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, et al. Problem adaptation therapy for older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry. 2015;72(1):22–30. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham JG, Choi N, Seitz DP. Meta-analysis of problem solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;31(5):526–535. doi: 10.1002/gps.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok RM, Nolen WA, Heeren TJ. Efficacy of treatment in older depressed patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials with antidepressants. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141(2–3):103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X, Xiao H, Chen Y. Effects of life review interventions on psychosocial outcomes among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2017;17:1344–1357. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreville P, Bissonnette L. Effects of cognitive bibliotherapy for depressed older adults with a disability. Clinical gerontologist. 1997;17(4):35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Landreville P, Gervais PW. Psychotherapy for depression in older adults with a disability: where do we go from here? Aging & Mental Health. 1997;1(3):197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lenze E, et al. Older adults’ perspectives on clinical research: a focus group and survey study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(10):893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Jones R, et al. Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 1999;319(7211):676–682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks T, et al. A Tune in “A Minor” Can “B Major”: A Review of Epidemiology, Illness Course, and Public Health Implications of Subthreshold Depression in Older Adults. Journal Of Affective Disorders. 2011;129(1–3):126–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J. A community based survey of older adults’ preferences for treatment of anxiety. Psychology and Aging. 2011;27(4):1182–1190. doi: 10.1037/a0023126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Mhaolain AM, et al. Frailty, depression, and anxiety in later life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(8):1265–1274. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyunt M. Community screening, outreach and primary care management of late life depression. National University of Singapore; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Orgeta V, Brede J, Livingston G. Behavioural activation for depression in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.205021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti M, et al. Association Between Chronic Physical Conditions and the Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(9):978. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodda J, Walker Z, Carter J. Depression in older adults. British Medical Journal. 2011;343:d5219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch FB, et al. Exercise for depression in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials adjusting for publication bias. 2016;15:1–8. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2016-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano JP, et al. Life Review Therapy Using Autobiographical Retrieval Practice for Older Adults With Depressive Symptomatology. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):272–277. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simning A, Simons KV. Treatment of depression in nursing home residents without significant cognitive impairment: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2017;29(02):209–226. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2011;343(7109):d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre. Review Manager (RevMan) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tunvirachaisakul C, et al. Predictors of treatment outcome in depression in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017 Apr;227:164–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan L, Corbin AL, Goveas JS. Depression and frailty in later life: A systematic review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2015;10:1947–1958. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S69632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K, et al. Age variation in the diagnosis and management of depression in adults aged 55 and over: an analysis of a large primary care database. Psychological Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, et al. Twelve-Month Use of Mental Health Services in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K, et al. Anxiety disorders in older adults: A comprehensive review. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(2):190–211. doi: 10.1002/da.20653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.