Abstract

Introduction

There are gaps in the primary healthcare (PHC) delivery in majority of low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to epidemiological transition, emergence of outbreaks or war, and often lack of governance. In LMICs, governance is always a less focused aspect, and often limited to the role of the authority despite potential contribution of other actors. It is evident that community engagement and social mobilisation of health service delivery result in better health outcomes. Even in case of systems failure, the need for PHC services is satisfied by individuals and communities in LMICs. Available evidence including systematic reviews on PHC governance is mostly from high-income countries and there is limited work in LMICs. This evidence gap map (EGM) is a systematic exploration to identify evidence gaps in PHC policy and governance in this region.

Methods and analysis

Different bibliographic databases were explored to retrieve available studies considering the time period between 1980 and 2017, and these were independently screened by two reviewers. Screened articles will be considered for full-text extraction based on prespecified criteria for inclusion and exclusion. A modified SURE (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence) checklist will be used to assess the quality of included systematic reviews. Overview of the findings will be provided in synthesised form. Identified interventions and outcomes will be plotted in a dynamic platform to develop a gap map.

Ethics and dissemination

Findings of the EGM will be published in a peer-reviewed journal in a separate manuscript. This EGM aims to explore the evidence gaps in PHC policy and governance in LMICs. Findings from the EGM will highlight the gaps in PHC to guide policy makers and researchers for future research planning and development of national strategies.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018096883.

Keywords: evidence gap map, primary health care, policy, governance, lmics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This evidence gap map (EGM) protocol follows the strong methodological approaches of theInternational Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) EGM.

This EGM will guide policy makers in implementing better strategies in primary healthcare (PHC).

Only systematic reviews and impact evaluations are included in this EGM.

As the articles written in languages other than the English are not included, it is likely to miss few relevant articles written in those languages.

This EGM will explore the available interventions and outcomes in PHC governance, but the measurement and assessment of the impact of different interventions will not be assessed; for this reason, certain important issues such as measurement of equity effects will be unexplored.

Introduction

The concept of primary healthcare (PHC) is a fundamental component of health service delivery which underwent tremendous evolution to identify its preliminary role. Starting from the broader definition during the Alma Ata Declaration to the latest targets of sustainable development goals, PHC is the foundation for effective health service delivery and majority of healthcare needs.1 Despite notable progress in the last three or four decades,2 there are still gaps in PHC delivery in many low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs)3–6 due to epidemiological transition,1 emergence of outbreaks7 or war, and sometimes lack of governance.4

The term governance more specifically reflects the role and responsibility of political, social and economic actors and administrative authority,8 9 which is more crucial in health systems due to engagement of multiple stakeholders. In LMICs, governance has always received less attention in comparison with other building blocks of health systems,10 and is sometimes limited to the role of the government or authority despite the potential contribution of other actors, such as local health workers, the community and the local health market.11 It is evident that community engagement and social mobilisation for health service delivery result in better health outcomes in terms of quality, accountability and uptake.12 Even in case of systems failure, the need for PHC services is satisfied by individuals and communities in LMICs.13

A number of frameworks have been developed focusing on non-governmental actors of health systems.14 In resource-poor settings with poor PHC regulation, models such as the common pool resource framework are applicable.15 Through extensive review and research, these thoughts conceived the development of a multilevel framework that explains the complex interaction at different domains of governance, focusing on operational, collective and constitutional governance.16 Depending on who and how the supply and demand of PHC services in a community are influenced, this multilevel framework incorporates individuals and providers within the local health service delivery (operational governance), collective actions by communities or representatives within the broader health systems (collective governance), and finally the decisions and actions of influential actors at different levels of government and non-governmental stakeholders, such as national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), donor groups, and global health organisations (constitutional governance).16 17 This framework incorporates all these different levels of health systems actors and offers a people-centred lens on PHC governance, making it more viable for use in terms of understanding the potential impact of PHC service delivery and how each level of action impacts the other in PHC governance. This framework also considers the fact that a health systems actor may belong to different categories of governance depending on the actions they perform and the decisions they influence. The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) framework is derived from the vigorous review of existing health systems frameworks, and the core of the framework comprised service delivery. To assess PHC system activities and identify gaps, the PHCPI framework sets some vital key indicators. The following are the queries on governance: reflected importance of PHC in policies and active engagement of stakeholders.1

Most of the available evidence, including systematic reviews, on PHC governance is from high-income countries,18 and in many cases systematic reviews ended with studies from high-income countries only.19 20 Literature review revealed a systematic review examining strategic areas, especially PHC for women and workforce development in Sub-Saharan Africa.21 Another systematic review focused on the structures and healthcare delivery patterns of the three models of PHC providers in China.22 The supervision-related interventions got minimal positive effects on some of the outcomes as per a systematic review.23 Moreover, accountability mechanisms were highlighted as important governance tools, although existing evidence showed that the interactions between two forms of accountability (external and bureaucratic accountability) have been occasionally emphasised.14 Contracting out the delivery of PHC services is often promoted to use the resources of the private sector, for filling supply-side gaps in the public system, and for making PHC services more accountable and transparent.24 25 The first experience with this approach to service delivery occurred in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in the 1980s, and since the 1990s the approach has been increasingly adopted by LMIC governments.25 The formation of social compacts and the process of community mobilisation around the revitalisation of PHC were given importance in an Eastern Cape regional PHC programme.26 An impact evaluation of a government franchise programme in Vietnam reflected the significant association between franchise membership and community perception and satisfaction in PHC service delivery.27 The area covered by the term governance is broad and not well defined. Different interventions have been applied to improve governance at different levels, but still there is broad evidence gap with regard to the appropriate interventions in different contexts and their relevant outcomes. Exploring these gaps can be the basis for future research field and may identify potential areas where specific interventions are needed and appropriate.

Objective

In line with achieving universal health coverage, one of the key issues that need much research and work is PHC governance. This evidence gap map (EGM) is an attempt to identify evidence gaps in PHC policy and governance in LMICs to accelerate improvement.

Methods

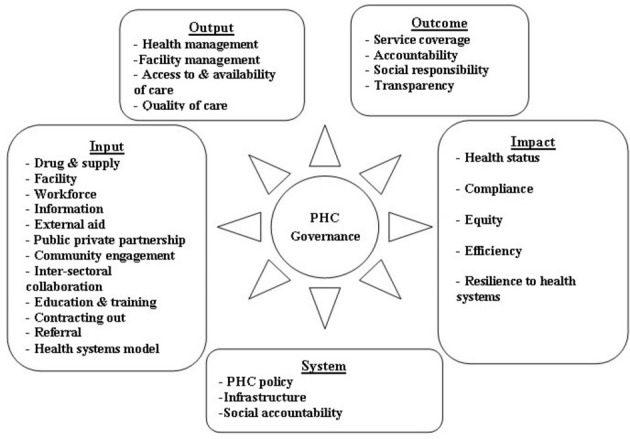

EGM is the mapping out of existing systematic reviews and primary studies in a specific field. It also provides a visual presentation of existing evidence using a framework of interventions and outcomes. This EGM protocol has been developed addressing the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) EGM guidelines and recommendations.28 This will be reported according to the guidelines of the Reporting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses (ROSES).29 A systematic search of the literature will be conducted based on a comprehensive search strategy which has been developed from the objectives and proposed conceptual framework (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adapted conceptual framework for primary healthcare (PHC) policy and governance.

Overview of the scope of the PHC EGM

The conceptual framework for improving PHC governance has been adapted in the context of policy and governance through an extensive literature review and stakeholder consultation with leading experts, including government high officials and policy makers who are working in the field of PHC. ‘Governance’ is the main focus of this framework. The framework encompasses a complete pathway from existing health systems to impact on PHC. The framework emphasises the interactions between providers, communities, patients and the quality of services. The adapted framework demonstrates people-centred and community-centred care, and supply and demand functions. It also describes a combined approach of service delivery through effective management of workforce and interactive collaboration and partnership among relevant sectors and organisations. This framework focuses on key components that provide direction in achieving outcomes based on which the ultimate impact will be achieved.

The successful interaction of systems and inputs contributes to PHC outputs, outcomes and impact. As a result of the mentioned input, the focus goes to the management of facility which has influence on accessibility, availability and quality of care. Notably, these domains focus on service coverage and on accountability and social responsibility of both providers and consumers. The final domain, ‘Impact’, is influenced by all preceding domains. This domain is focused on mortality and morbidity, as well as the major impact of people-centred care such as compliance, equity, efficiency and resilient health systems.

This EGM is an overview of impact evaluations and systematic reviews corresponding to the policy and governance in PHC to identify the gaps of existing evidence in LMICs.

Here, the substantive scope of EGM study is described under key components: PHC, interventions and outcomes. To keep the scope expedient, some key categories were outlined to develop a comprehensive search strategy for inclusion of relevant literature.

The team developed a draft framework consisting of interventions and outcomes related to PHC which was based on the conceptual framework. The framework was finalised by consulting with an expert group which was composed of government high officials working on PHC and health system researchers. This expert consultation was held at the inception stage to define the scope of mapping in January 2018.

Eligibility criteria

A prespecified set of criteria will be applied for the selection process of available studies. Population, intervention, outcome and types of evidence are described below.

Participants

Although the general inclusion criteria allowed only studies performed in LMICs as per the definition of the World Bank,30 systematic reviews which may have reviewed studies in high-income countries were included if these reviews also contained studies performed in LMICs. If a review only considered literature on interventions implemented in high-income countries, it was excluded.

Interventions

This EGM will cover programmes and interventions implemented by governments, NGOs, international organisations or donor agencies to manage PHC policies and governance.

The adopted conceptual framework was the basis for prolepsis and categorising the intervention that might influence the status of PHC policy and governance. As the overall scope was very broad—covering all relevant dimensions of policy and governance in PHC—it was feasible to include all possible interventions by categorising them. Table 1 presents the interventions which were most commonly covered by the programmes implemented by the governments independently or in support of NGOs or development partners.

Table 1.

Categories of interventions and outcomes

| Intervention categories | Outcome categories | |||||

| Health systems | Workforce | Infrastructure | Community-related | Facility management | Quality of care | Compliance |

| Primary healthcare policy | Workforce management | Facility | Public–private partnership | Healthcare management | Service coverage | Accountability |

| Health system model | Information | Drug and supply | Community engagement | Health facility management | Health status and health outcome | Social responsibility |

| Intersectoral collaboration | Education and training | External aid | Social accountability | Access to and availability of care | Resilience to health systems | Transparency |

| Referral | Contracting out | Equity | Efficiency | |||

Outcomes

According to our conceptual framework, the outcomes are organised by the study objective. The possible outcomes are underlying some broader categories such as facility management, quality of care and compliance. Table 1 describes the detailed outcome of the EGM.

Study design

The EGM will include both impact evaluations and systematic reviews of effects on PHC policy and governance. Impact evaluations consist of randomised controlled trial, controlled before and after study, and cross-sectional studies with an intervention and comparison group using methods to control for selection bias and confounding

Exclusion criteria

Studies conducted in countries other than LMICs will be considered for exclusion. Observational studies with no control, efficacy trials such as surveys, and non-systematic literature reviews will be sorted for exclusion. Ongoing trials and reviews, trial or review protocols will be excluded. Letters to the editor, editorial comments and conference papers will also be excluded. We will exclude the articles that have been published before January 1980 or written in language apart from English.

Information sources

Following electronic bibliographic databases, impact evaluation databases, systematic review databases, bilateral agencies, and databases of the United Nations and international NGOs will be searched systematically using a comprehensive search strategy. The bibliographic databases are MEDLINE through PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Popline, Scopus, and Informit Humanities and Social Sciences. Impact evaluation databases include the 3ie Impact Evaluation Repository, World Bank: Development Impact Evaluation Initiative, Asian Development Bank: Independent Evaluation, World Bank: Independent Evaluation Group, US Agency for International Development (USAID): Development Experience Clearinghouse, African Development Bank: Evaluation Reports, and Department for International Development (DFID): Evaluation Reports. Systematic review databases are Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Joanna Briggs systematic reviews, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and co-ordinating Centre (EPPI) systematic reviews database, Campbell Collaboration database, 3ie database of systematic reviews and PHC evidence. Bilateral aid agencies such as Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) - formerly AusAID, DFID, USAID, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), The Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ), and the United Nations database such as WHO, UNDP, UNFPA, and Unicef international NGOs/additional references from advisory groups will be searched. The search strategy will be developed considering relevant terms which will describe the population, intervention and outcome. In addition to the electronic databases, hand-searching for grey literature and selective snowballing will be conducted.

Stakeholder engagement

A preliminary exploration of the published policy and governance-related peer-reviewed literature in terms of PHC will be performed. A draft framework consisting of interventions and outcomes based on PHC in existing literature will be developed. Those intervention and outcome categories will be finalised by consultation with relevant stakeholders and expert group. The stakeholder group will be composed of government high officials working with PHC and health system researchers.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy will be developed for MEDLINE. For other bibliographic databases, key search terms will be sorted and database-specific filters will be applied, where available. The key search terms for population, intervention, comparison and outcome are shown in table 2. Comprehensiveness of the search strategy will be assessed by cross-checking with benchmark articles.

Table 2.

Key terms describing the population, intervention and outcome

| Population (P) | Intervention (I) | Outcome (O) | Filter |

| LMICs. “Developing country”. |

“Health systems model”. “Governance model”. “Workforce management”. “Community engagement”. “Public private”. |

Policy. Governance. Accountability. “Social responsibility”. Compliance. |

“Primary Healthcare”. PHC. |

LMICs, low-income and middle-income countries; PHC, primary healthcare.

Only English-language literature published between January 1980 and December 2017 will be searched. The comprehensive search strategy for searching PubMed is provided in table 3.

Table 3.

Search strategy: PubMed format

| 1 | LMIC’s |

| 2 | (Models AND “health system”) OR (Models AND governance) OR “workforce management” OR (workforce AND management) OR Assessment OR “priority setting” OR strategy OR (Community AND engagement) OR “Community engagement” OR (external AND aid) OR “health literacy” OR (public AND private) OR “public private” |

| 3 | “Policy” (Mesh) OR Governance OR “Social Responsibility” (Mesh) OR (Social AND responsibility) OR purchas* OR corruption OR coordination OR compliance |

| 4 | Primary healthcare(MeSH Terms) OR “primary Healthcare” (Text Word) OR PHC(Text Word) |

| 5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

| 6 | Restrict #5 to year=1980 and 2017 |

| 7 | Restrict #6 to English language |

Search strategy for low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) is provided as online supplementary file.

bmjopen-2018-024316supp001.pdf (12KB, pdf)

Study records

Data management

After a comprehensive search of articles, the EndNote software will be used to organise and manage the retrieved articles. Articles retrieved from different electronic bibliographic databases will be compiled and organised in an EndNote library. Reviewers will check for any duplication and remove the duplicate articles. Articles retrieved from bilateral agencies and United Nations agencies will be maintained using an Excel sheet.

Screening process

Screening of the retrieved articles will be conducted in two phases. Two independent reviewers will screen the articles considering the title and the abstract of the articles to include based on the inclusion criteria. Predefined coding for inclusion and exclusion criteria will be used. An Excel database will be maintained to keep record of search screening. In the second phase of screening, articles initially included will be assessed considering their full text to finalise the inclusion process. Two reviewers will independently perform this stage as well, and any disagreement in the process will be discussed with a third reviewer and resolved. Record keeping will be maintained for reasons of exclusion. A summary of the process, including the numbers of excluded and included articles, will be presented using the ROSES flow diagram.29

Data extraction

A standardised form will be used to extract data, where information will be gathered on publication year, geographical location of the studies, population of the study, research design, details of the intervention on PHC governance and measurements of outcome. Information on the assessment of the quality of the included systematic reviews will also be extracted. Throughout the process, two reviewers will extract data independently. A third reviewer will randomly check the data extraction process and resolve any dispute between the primary reviewers.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included systematic reviews will be assessed using a standardised tool for critical appraisal used by the 3ie EGM group. Systematic reviews will be provided an overall rating of high-grade, medium-grade or low-grade evidence in terms of the confidence with which their findings can be assured. The checklist28 is adapted by 3ie from the checklist developed by the SURE (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence) collaboration. The quality of the included systematic reviews will be assessed by two independent people, and a third reviewer will check and finalise the assessment. Included impact evaluations will not be considered for quality assessment.

Strategy for data synthesis

A descriptive synthesis of the interventions and outcomes of the systematic reviews and impact evaluations will be narrated. Year-wise distribution of the impact evaluations and systematic reviews will be demonstrated. Geographical distribution of the included articles will be presented using a geographical information system map. Frequency distribution of the interventions focusing on PHC policy and governance will be shown graphically. Outcomes of the interventions will be explored and demonstrated. Identified interventions and outcomes will be plotted in a dynamic platform to develop a visual gap map. Studies can be plotted in multiple places in the EGM if they considered several outcomes or interventions. It will be possible for users to understand the grade of evidence by visual inspection due to the use of colour codes that mention the quality of evidence.

Patient and public involvement

This is a protocol for EGM, and there is no direct involvement of patients in the whole process of EGM development. This EGM has been developed for the overall betterment of PHC and to explore basis for future research.

Publication plan

Details of the findings and the dynamic EGM will be published in a separate manuscript.

Timeline

Review start date: 1 January 2018.

Review finish date: 30 September 2018.

Reporting date: 15 January 2019.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

icddr,b is grateful to the governments of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support.

Footnotes

Contributors: KMSUR and RM conceptualised the EGM in consultation with the coauthors. KMSUR wrote the first draft of this protocol with substantial inputs from all authors. KMSUR and RM contributed to the planning for literature search. Plan for screening, collection and analysis of data for all the included systematic reviews and impact evaluations are conducted by KMSUR and RM with close consultation from IA. All authors provided input, reviewed and finalised the paper before dissemination. The corresponding author is the guarantor of this EGM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This publication is based on research of icddr,b funded by Ariadne Labs through Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which is a recipient of a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: As this EGM is based on published articles, formal ethical assessment and informed consent are not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: Any updates or amendments to this protocol will be described, including the date of each amendment, description of the change and rationale for the change. The PROSPERO register will remain updated with the protocol and amendments.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Bitton A, Ratcliffe HL, Veillard JH, et al. . Primary Health Care as a Foundation for Strengthening Health Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:566–71. 10.1007/s11606-016-3898-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rohde J, Cousens S, Chopra M, et al. . 30 years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries? Lancet 2008;372:950–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61405-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams AM, Islam R, Ahmed T. Who serves the urban poor? A geospatial and descriptive analysis of health services in slum settlements in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan 2015;30(Suppl 1):i32–45. 10.1093/heapol/czu094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Das J, Hammer J. Quality of Primary Care in Low-Income Countries: Facts and Economics. Annu Rev Econom 2014;6:525–53. 10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-041350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hansen PM, Peters DH, Edward A, et al. . Determinants of primary care service quality in Afghanistan. Int J Qual Health Care 2008;20:375–83. 10.1093/intqhc/mzn039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sylvia S, Shi Y, Xue H, et al. . Survey using incognito standardized patients shows poor quality care in China’s rural clinics. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:322–33. 10.1093/heapol/czu014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delamou A, El Ayadi AM, Sidibe S, et al. . Effect of Ebola virus disease on maternal and child health services in Guinea: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e448–e57. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30078-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ. Health governance: concepts, experience, and programming options: Abt associates. 2008.

- 9. United Nations Development Programme. Governance for sustainable human development: a UNDP Policy Document: United Nations Development Programme, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bossert TJ. Health systems. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:8–10. 10.1093/heapol/czr008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rifkin SB. Lessons from community participation in health programmes: a review of the post Alma-Ata experience. Int Health 2009;1:31–6. 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCoy DC, Hall JA, Ridge M. A systematic review of the literature for evidence on health facility committees in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:449–66. 10.1093/heapol/czr077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ola A, Jimoh U. Coping with infrastructural deprivation through collective action among the rural people of Oyun Lga, Kwara State, Nigeria. Journal of Public Policy & Governance 2015;2:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cleary SM, Molyneux S, Gilson L. Resources, attitudes and culture: an understanding of the factors that influence the functioning of accountability mechanisms in primary health care settings. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:320 10.1186/1472-6963-13-320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosato M, Laverack G, Grabman LH, et al. . Community participation: lessons for maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet 2008;372:962–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abimbola S, Negin J, Jan S, et al. . Towards people-centred health systems: a multi-level framework for analysing primary health care governance in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:ii29–39. 10.1093/heapol/czu069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGinnis MD. An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom workshop: a simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Studies Journal 2011;39:169–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dawson AJ, Nkowane AM, Whelan A. Approaches to improving the contribution of the nursing and midwifery workforce to increasing universal access to primary health care for vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:97 10.1186/s12960-015-0096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gibson O, Lisy K, Davy C, et al. . Enablers and barriers to the implementation of primary health care interventions for Indigenous people with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2015;10:71 10.1186/s13012-015-0261-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hedden L, Barer ML, Cardiff K, et al. . The implications of the feminization of the primary care physician workforce on service supply: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:32 10.1186/1478-4491-12-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown L, Lee TH, De Allegri M, Rao K, et al. . Applying stated-preference methods to improve health systems in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2017;17:441–58. 10.1080/14737167.2017.1375854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li H, Qian D, Griffiths S, et al. . What are the similarities and differences in structure and function among the three main models of community health centers in China: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:504 10.1186/s12913-015-1162-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bosch-Capblanch X, Garner P. Primary health care supervision in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:369–83. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmer N. The use of private-sector contracts for primary health care: theory, evidence and lessons for low-income and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:821–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosenau PV. Introduction: The strengths and weaknesses of public-private policy partnerships. 43: Sage Publications, 1999:10–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olver CB, Kruger T, Morran D. Assignment report: revitalising Primary Health Care in the Eastern Cape: Human Development Resource Centre, UK, 2011:68. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ngo A, Phan H, Pham V, et al. . Impacts of a government social franchise model on perceptions of service quality and client satisfaction at commune health stations in Vietnam. Journal of Development Effectiveness 2009;1:413–29. 10.1080/19439340903370477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Snilstveit B, Vojtkova M, Bhavsar A, et al. . Evidence & Gap Maps: A tool for promoting evidence informed policy and strategic research agendas. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;79:120–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, et al. . ROSES RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environmental Evidence 2018;7:7 10.1186/s13750-018-0121-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. The World Bank. “Country Groups,” Data and Statistics: The World Bank, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024316supp001.pdf (12KB, pdf)