Abstract

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a new potential surgical treatment for opioid dependence. However, the implement of DBS treatment in addicted patients is currently controversial due to the significant associated risks. The aim of this study was mainly to investigate the therapeutic efficacy and safety of bilateral DBS of nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule (NAc/ALIC-DBS) in patients with refractory opioid dependence (ROD).

Methods and analysis

60 patients with ROD will be enrolled in this multicentre, prospective, double-blinded study, and will be followed up for 25 weeks (6 months) after surgery. Patients with ROD (semisynthetic opioids) who meet the criteria for NAc/ALIC-DBS surgery will be allocated to either the early stimulation group or the late stimulation group (control group) based on the randomised ID number. The primary outcome was defined as the abstinence rate at 25 weeks after DBS stimulation on, which will be confirmed by an opiate urine tests. The secondary outcomes include changes in the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score for craving for opioid drugs, body weight, as well as psychological evaluation measured using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence assessment, social disability screening schedule, the Activity of Daily Living Scale, the 36-item Short Form-Health Survey and safety profiles of both groups.

Ethics and dissemination

The study received ethical approval from the medical ethical committee of Tangdu Hospital, The Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China. The results of this study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at international conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT03424616; Pre-results.

Keywords: deep brain stimulation, nucleus accumbens, opioid relapse prevention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first multicentre research protocol for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of bilateral nucleus accumbens-deep brain stimulation (DBS) in patients with refractory substance dependence.

There is a risk of recruiting patients with severe opiate abuse disorders despite our strict inclusion criteria.

Another limitation of this study protocol is the extensive burden of monitoring required of patients, and outpatient follow-up for 4 weeks, 12 weeks and 25 weeks after DBS stimulation requires the consent of patients.

Introduction

Background and rationale

Substance dependence is a functional brain disease characterised by behavioural pathology involving compulsive drug seeking and consumption with progressive loss of control over drug intake, which leads to a number of adverse social and health consequences for the addicted subjects.1 Heroin and other opiates are the drug category with the highest burden of substance dependence are more severe than any other group of illicit drugs.2 Moreover, the abuse of opiates has emerged as a major international public health concern within the past decade.3 The medical treatment of substance dependence still mainly relies on maintenance treatment with a controllable and less dangerous medical substitute.4 5 Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is often advocated as a reversible alternative to neurosurgery, and it is a potentially new treatment for opiates dependence and other substances abuse.6 Based on the knowledge of the importance of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) in addiction, the idea of DBS of the NAc to treat alcohol and smoking addiction has been pursued since 2007.7–12 The concept of treating addiction via NAc-DBS has recently been broadened to heroin addiction, and is supported by evidence from animal models.13–17 The anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC), which contains superolateral part of the medial forebrain bundle carrying dopaminergic projections from ventral tegmental area to forebrain limbic structures, underlie the pathophysiology of several psychiatric disorders including addiction as well,18–20 making ALIC to be another possible targets for addiction treatment. Though the implementation of DBS in patients with refractory substance dependence is currently still controversial,7 12 21 the reversible feature and less invasion to the brain tissue still make DBS to be a possible choice for addiction therapy, considering its superior to other conventional methods for relapse prevention according to other and our previous reports.22–24 Some recommendations from experts in this field support the use of DBS only in patients in which at least three addiction treatments in the hospital or compulsive rehabilitation have failed. NAc-DBS has been considered as an early therapeutic intervention with the aim of improving the quality of life and giving patients who have failed rehabilitation more than three times a chance to undergo a possible therapeutic treatment for opioid addiction.22 25–28 Recent studies indicate that DBS would be similarly cost-effective in treating opiate addiction to methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), which makes it a promising therapeutic method for the treatment of addiction.6 16 28 Thus far, no multicentre prospective and double-blinded study has been performed in China to investigate the efficacy, safety and adverse effects (AEs) of NAc-DBS as an alternative treatment for opiate dependence.

Objectives

The study termed DBS of the NAc and ALIC for opioid relapse prevention (NAc-DBSORP) was initiated in May 2018 and is anticipated to be concluded by July 2020. The primary objective of this study is to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the abstinence rate between the early stimulation group and the late stimulation group (control group) from baseline to 25 weeks after DBS surgery. Additional objectives are to summarise or characterise: the total days of ORP, the longest duration of prevented opioid relapse, the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) craving score for opioid drugs, body weight, the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence assessment (FTND), the social disability screening schedule (SDSS), the Activity of Daily Living Scale (ADL), the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the safety profiles for both groups based on severe AEs reported throughout the study.

Methods and analysis

Patient and public involvement

The study was consulted and reviewed by patient representatives during the protocol development. And two patients have been invited to join the project advisory group. They were asked to offer a proposal about recruitment strategy, visit schedule and benefits of the study participants. Investigators asked about their experience of assisted conception, the things they liked and disliked, and the potential difficulties or barriers to attending for treatment, randomised allocation and how this might affect recruitment. During the 25 weeks follow-up, the burden of the intervention for patients will be assessed by investigators and consulted by family members of patients. On completion of the trial, the results will be summarised in both plain Chinese and English, and distributed to participants and patient support groups with the assistance of collaborators in our study.

Study design and setting

NAc-DBSORP is a Chinese, multicentre, prospective and double-blinded study. Patients will be recruited by four centres in China, comprising (1) Tangdu Hospital of the Fourth Military Medical University (affiliation of the principal investigator, PI), Xi’an; (2) Ruijin Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai; (3) West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu and (4) Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou. The specified data centre is the First Affiliated Hospital of Peking University, Beijing. The statistical analysis will be conducted at the First Affiliated Hospital of Peking University.

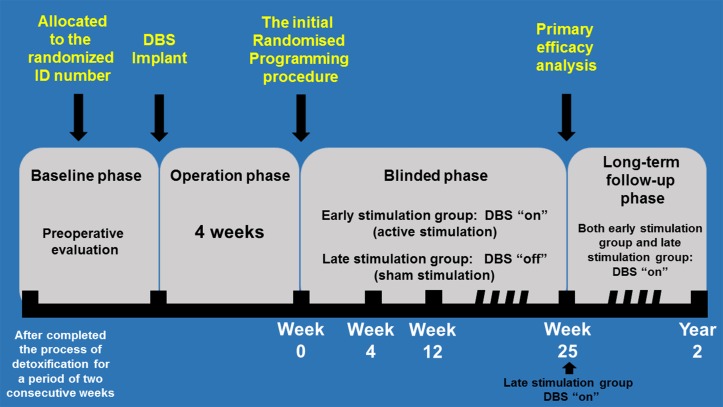

All the patients voluntarily came to our institution and chose to receive the surgery independently after they were given the recruitment information, after which they signed informed consent forms (ICFs). As shown in figure 1, all recruited participants will be allocated to either the early stimulation group (study group) or the late stimulation group (control group) based on the randomised ID number after the 2–3 days recruitment. Then both groups of patients will undergo the DBS surgery. Four weeks after surgery, all patients will visit the clinic with the DBS stimulation in the ‘off’ state for initial programming of electrical parameters for stimulation. The patients will then be assigned to one of two groups, that is, the early stimulation group and late stimulation group, by a randomised allocation system (SceneRay, Suzhou, China) integrated into the programmer according to the randomisation plan completed preoperatively.

Figure 1.

Study design and setting. DBS, deep brain stimulation.

For the early stimulation group, the electrical stimulation will be actually ‘turned on’ immediately after the initial programming, while for the late stimulation group, the electrical stimulation will be actually off after the initial programming. The randomised allocation system integrated into the programmer will guarantee that both investigators and patients do not know the grouping situations. The initial programming procedures and parameters were fixed for all patients and the initial programming procedure was completely the same just according to the operation interface of the programmer (achieved by the randomised allocation system integrated into the programmer), so that both the investigators and patients will be blinded to the actual status of the stimulation after the programming, that is, if DBS was initially on or off. The stimulation status will remain unchanged for both groups until 25 weeks after the initial programming, when the grouping of the study will be unblinded and all data will be collected. However, according to the ethical principles of clinical trials, if a relapse occurs for either groups of patients during the 25-week study period, the grouping status for the relapsed cases should be unblinded and these patients should immediately receive proper treatment after relapse. All such patients should repeat the process of detoxification (no less than 10 days), after which the implantable pulse generator (IPG) will be actually turned on for patients either from the early stimulation group (study group) or the late stimulation group (control group). It should be noted that these conditions will not affect the primary endpoint measurement when the 25-week study period ends. When the 25-week study period ends, the stimulation will be kept turned on for all patients. Especially, for the patients in the late stimulation group who remain abstinent until this time point, the stimulation will be turned on as well. After the study has ended, follow-up for the patients will be continued, the frequency and methods of which will be decided by investigators themselves.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients will be eligible for recruitment if they meet the following criteria: (1) aged 18–50 years old; (2) severe abuse disorders involving semisynthetic opiates (fulfilling the diagnostic criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition): (a) history of opiate abuse no less than 3 years, (b) failure of at least three addiction treatments or medication (especially MMT and compulsive rehabilitation), (c) completion of detoxification (negative urine test for morphine, methamphetamine, ketamine and buprenorphine, no less than 10 days); (3) the patients who request surgical treatment have normal cognitive status and ability to understand the benefit and risk of the treatment; (4) the patient shows good compliance, and the relatives of the patient can assist the researchers to complete the follow-up and (5) complete ICFs.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with one of the following conditions will be excluded: (1) clinically relevant psychiatric comorbidity (schizophrenic psychoses, bipolar affective diseases, severe personality disorder); (2) contraindications for an MRI examination, for example, implanted cardiac pacemaker/heart defibrillator; (3) abuse of other types of drugs; (4) severe cognitive impairments; (5) enrolment in other clinical trials; (6) stereotactic or other neurosurgical intervention in the past; (7) contraindications against a stereotactic operation, for example, increased bleeding disposition, cerebrovascular diseases (eg, arteriovenous malfunction, aneurysms, systemic vascular diseases); (8) serious and unstable organic diseases (eg, unstable coronal heart disease); (9) tested positively for HIV; (10) pregnancy and/or lactation; (11) severe disorders of coagulation and liver function and (12) epilepsy or other severe brain trauma or neurological impairment.

Procedures

Instruments

The VAS is used for patients by self-reporting the degree of craving for drugs, with ‘0’ indicating ‘no craving’ and ‘10’ indicating ‘extreme craving’.24

The HAMD-17 is a multiple-item questionnaire used by clinicians to provide an indication of depression, with higher total HAMD scores indicating higher severity of depression for patients.29

The HAM-A is a psychological questionnaire used by clinicians to rate the severity of a patient’s anxiety, with higher total HAM-A scores indicating higher severity of anxiety for patients.30 31

The PSQI is a self-reporting questionnaire that assesses sleep quality for patients over a 1-month time period, consisting of 19 individual items, creating 7 components that produce one global score, with lower scores denoting a healthier sleep quality.32 33

The FTND is a self-reporting tool for assessing nicotine addiction by conceptualising dependence through physiological and behavioural symptoms. A higher total FTND score indicates more intense physical dependence on nicotine.34 35

The SDSS is part of the disability assessment schedule edited by WHO, which is a self-reporting tool for indicating social disability of patients, with higher scores denoting more social disability.36

The ADLs scale is a questionnaire used by clinicians to assess the ability of patients to independently perform the ADLs. The scores for ADL range from 14 to 56, with a score of 14 indicating completely normal ADLs and a score ≥20 indicating significant inability to perform the daily activities without assistance.37

The SF-36 is a patient-reported survey of patient health. The SF-36 consists of 8 scaled scores which represent the weighted sums of the questions in the respective sections, with lower scores denoting greater disability.38

The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery (MCCB), which is a package of 10 tests, provides a relatively brief evaluation of key cognitive domains relevant to schizophrenia and related disorders.39

All these instruments have been validated in Chinese, and the Chinese version of each instrument will be used in the present trial. In addition, the evaluation of withdrawal symptoms was done using the self-rating scale of protracted withdrawal symptoms for opiate dependence developed by Chen et al, which consists of 33 items.40

Baseline assessment

Patients with refractory opioid dependence with an intention of undergoing bilateral NAc-DBS will be screened and recruited by neurologists in an outpatient clinic. When a patient decides to participate in the study, the ICF will be signed and personally dated by the patient or legally authorised representative and the investigator. One copy of the signed ICF will be sent to the PI’s institute and one will be kept in the patient’s folder at the investigation site. After the recruitment, there will be at least a month for observation and preparation. During this period, the patients will have to complete the process of detoxification (negative urine test for morphine, methamphetamine, ketamine and buprenorphine, no less than 10 days) for a period of two consecutive weeks. They will then be admitted to the neurology department for preoperative evaluation, which includes (1) VAS craving score for opioid drugs; (2) demographic characteristics of the participants (such as gender, age, body weight and body mass index); (3) psychological evaluation including HAMD-17, HAM-A, PSQI, FTND, SDSS, ADL and SF-36 (4) evaluation of withdrawal symptoms; (5) MATRICS-test (MCCB) and (6) urine test. Those who meet the inclusion criteria will be admitted to the neurosurgery department for implantation of the DBS device. Patients who do not meet the inclusion criteria will be excluded from the study. Follow-ups will be scheduled for 25 weeks after surgery.

Surgery

All centres have the expertise to perform DBS surgery, with surgeons having more than 5 years of experience at the start of the trial. Surgical procedures between each centre may differ, but the following requirements will be met to guarantee an optimal approach: (1) DBS electrode placement was planned according to MRI findings using a Leksell Surgical planning system (SurgiplanTM, Elekta, Sweden). The coordinates at the tip of the most ventral contact (contact 0) will be placed were 8–10.5 mm from the midline, 15.5–18.5 mm anterior to the mid-commissural point and 4.5–8.5 mm below the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line for NAc; (2) Electrode implantation can be done under general anaesthesia, and the electrode leads will be externalised to confirm the electrode locations and to perform a temporary stimulation test; (3) Leads will be secured at the burr hole site using the Stimloc system (SN1710, SceneRay) and (4) The IPG (SN1181, SceneRay) will be implanted subcutaneously, usually at the right subclavicular area, during the same procedure as the electrodes.

The initial stimulation parameter programming

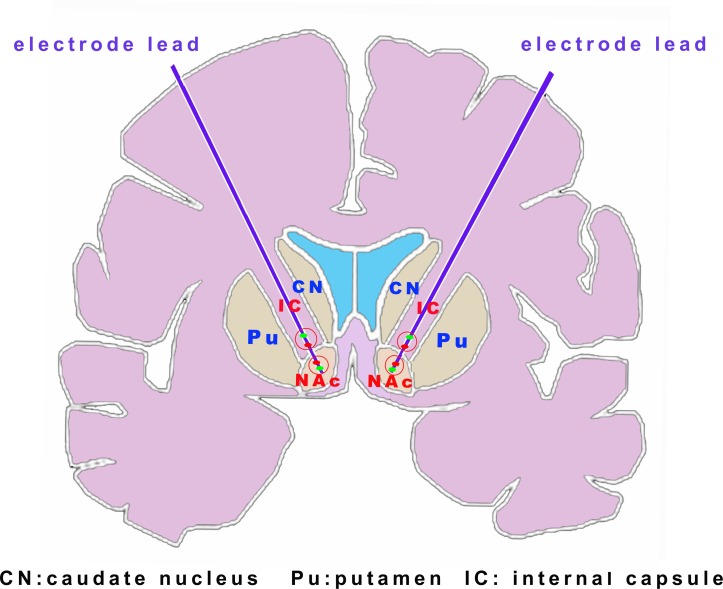

With the help of randomised allocation system integrated into the programmer, two measures were additionally performed to guarantee both the investigators and patients were blinded: (1) The procedure to titrate the simulation parameters in both groups were omitted; and thus (2) As shown in figure 2, the simulation parameters were fixed for all patients, with the two active contacts selected as one ALIC-ventral contact and one NAc-dorsal contact by postoperatively MRI (thus for most cases were the two middle contacts of the electrodes), and the stimulation parameters were fixed at a voltage of 3.0 V, pulse width of 210 μs and frequency of 165 Hz for ALIC-ventral active contact and a voltage of 3.0 V, pulse width of 210 μs and frequency of 145 Hz for NAc-dorsal active contact. Of note, these stimulation parameters were according to the experience from the previous studies and our single-centred preliminary study.22 24 41 42

Figure 2.

Simulated diagram for the initial stimulation parameter programming. The simulation parameters were fixed for all patients with the two active contacts selected as one ALIC-ventral contact and one NAc-dorsal contact (red dot). ALIC, anterior limb of the internal capsule; NAc, nucleus accumbens.

Sample size

In order that more patients can be allocated to the early stimulation group (receiving ‘true’ but not ‘sham’ intervention), which make trial representing more ethical considerations and make recruitment more easier (patients were informed that they have more chance to be allocated into the early stimulation group), the statistical experts decided the sample ratio to be 2:1 for treatment group:control group, which has been applied for most previous similar trials. Calculation of the sample size was further done by statistical experts designated by China Food and Drug Administration that was in charge of the quality control and approval for clinical trials, based on the primary outcome of the abstinence rate reported by previous literatures.24 43 Based on retrospective analysis of our previous data, the abstinence rate from baseline to 25 weeks after DBS surgery was 70% in 11 patients with opioid dependence, and previous studies showed that the abstinence rate of patients with opioid dependence who do not receive any treatment is around 30%.4 5 A two-sample test will be used to determine if the mean of the treatment group (μA) is different from that of the control group (μB). The hypotheses are: H0: μA−μB=0, H1: μA−μB≠0. The sample size will be calculated using the PASS V.11 sample size calculation software (NCSS, USA). Based on tests for two means, with a two-sided significance level of 5% and statistical power at 80%, allowing for a 15% drop-out rate, a sample size of 60 patients will be needed to test the hypothesis with the two-sided test. This will consist of 40 patients for the treatment group and 20 patients for the control group.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome: the abstinence rate which was defined as non-relapsed cases/total participants×100%, at 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on.

The definition of non-relapsed cases: if the participants or their families report the drug use at the frequency of ≥2 times per week in two consecutive weeks, or the urine tests remain positive in two consecutive weeks, or failure of follow-up, the case was defined as relapse, otherwise, the cases will be defined as non-relapsed. These definitions will be applied for the consecutive follow-up period from turning the DBS stimulation on to 25 weeks afterwards.

The frequency of urine tests is planned as follows: first, the urine tests will be done once per week at a fixed time, then two randomised urine tests will be done every month, then this urine test plan will guarantee the power to find the relapsed cases as defined above.

Secondary outcomes will be measured based on: (1) the total days of ORP for participants (the entire time after DBS stimulation has been turned on); (2) the longest duration of ORP for participants (the entire time after DBS stimulation has been turned on); (3) VAS craving score for opioid drugs (time frame): baseline (preoperative), 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on; (4) body weight of the participants (time frame): baseline (preoperative), 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on; (5) psychological evaluation including HAMD-17, HAM-A, PSQI, FTND, SDSS, ADL and SF-36 (time frame): baseline (preoperative), 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on; (6) the evaluation of withdrawal symptoms (time frame): baseline (preoperative), 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on; (7) MATRICS-test (time frame): baseline (preoperative), 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on and (8) the rate of positive urine test results (times of urine test was positive/total times of urine test (time frame): 25 weeks after DBS stimulation has been turned on.

Data collection methods

Assessment of safety

Safety data will include all AEs, from the point of subject enrolment to the final follow-up visit or discontinuation, whichever comes first. Reports of AEs will minimally include the following information: date of event, diagnosis or description of the event, assessment of the seriousness, treatment, outcome and date.

Collection of data

Before the start of the study, investigators from each centre will be trained on proper data recording. Data collected from each patient will be transcribed in case report form (CRF) with a printed version and sent to the specified data centre (First Affiliated Hospital of Peking University, Beijing) every 2 months. A copy of the CRF will be placed in the subject’s folder at the investigation site. Three monitors will audit the contents of the CRF before the data are entered into the database. Personal data will be coded and made anonymous.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis will be conducted in the First Affiliated Hospital of Peking University. The parameters of interest will be mean changes of the observed values from baseline to the 25-week follow-up. The primary analysis will be a complete case analysis (ie, using only cases with complete data), supported by sensitivity analysis, where missing data will be filled in using the multiple imputation method. The number, timing, pattern and reason for missing data or drop-out will be reported, as well as their possible implications for efficacy and safety assessments. Statistical analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints will be performed within the framework of the generalised linear model with baseline adjustment. The scores of instrument scales will be introduced into the linear model. Summaries of continuous variables will be presented as means±SD for normally distributed data and as medians with IQRs for skewed data. Categorical variables will be presented as frequencies (percentages). Statistical analysis will be performed using SPSS V.19.0 (IBM). All statistical tests will be two tailed, and a p<0.05 is considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethics and dissemination

Informed consent will be obtained from all individual participants included in this study or their legal representatives. Any amendments to the study will be submitted to the ethical committee of Tangdu Hospital for review. The final study results and conclusions will be presented at international conferences and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Q. Ma and Y. Gu for their contribution to the design/content of the protocol. Suzhou SceneRay Medical Instrument, China provided all implanted material at no cost for all patients.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

LQ and SG contributed equally.

Contributors: XW, JS, SG and LQ contributed the conception and design of the study. WW, PW, NL and KY provided their area of expertise for protocol development. NL and XW arranged the meetings and took the minutes. LQ and XW drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and provided feedback and comments.

Funding: The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no 81671366 to XW) and National Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (grant no 81401104 to SG).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The analysis and usage of patient information for this study was approved by the ethics committee of Tangdu Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 2006;29:565–98. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carew AM, Comiskey C. Treatment for opioid use and outcomes in older adults: a systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;182:48–57. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teesson M, Marel C, Darke S, et al. . Long-term mortality, remission, criminality and psychiatric comorbidity of heroin dependence: 11-year findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study. Addiction 2015;110:986–93. 10.1111/add.12860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee JD, Friedmann PD, Kinlock TW, et al. . Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1232–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coviello DM, Cornish JW, Lynch KG, et al. . A multisite pilot study of extended-release injectable naltrexone treatment for previously opioid-dependent parolees and probationers. Subst Abus 2012;33:48–59. 10.1080/08897077.2011.609438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stephen JH, Halpern CH, Barrios CJ, et al. . Deep brain stimulation compared with methadone maintenance for the treatment of heroin dependence: a threshold and cost-effectiveness analysis. Addiction 2012;107:624–34. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03656.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trujols J, Manresa MJ, Batlle F, et al. . Deep brain stimulation for addiction treatment: further considerations on scientific and ethical issues. Brain Stimul 2016;9:788–9. 10.1016/j.brs.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuhn J, Lenartz D, Huff W, et al. . Remission of alcohol dependency following deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens: valuable therapeutic implications? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:1152–3. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.113092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuhn J, Lenartz D, Huff W, et al. . Remission of alcohol dependency following deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens: valuable therapeutic implications? BMJ Case Rep 2009;2009:bcr0720080539 10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mantione M, van de Brink W, Schuurman PR, et al. . Smoking cessation and weight loss after chronic deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens: therapeutic and research implications: case report. Neurosurgery 2010;66:E218 Discussion E18 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360570.40339.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Voges J, Müller U, Bogerts B, et al. . Deep brain stimulation surgery for alcohol addiction. World Neurosurg 2013;80:S28.e21–31. 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pisapia JM, Halpern CH, Muller UJ, et al. . Ethical considerations in deep brain stimulation for the treatment of addiction and overeating associated with obesity. AJOB Neurosci 2013;4:35–46. 10.1080/21507740.2013.770420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou H, Xu J, Jiang J. Deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens on heroin-seeking behaviors: a case report. Biol Psychiatry 2011;69:e41–2. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuhn J, Möller M, Treppmann JF, et al. . Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens and its usefulness in severe opioid addiction. Mol Psychiatry 2014;19:145–6. 10.1038/mp.2012.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li N, Gao L, Wang XL, et al. . Deep brain stimulation of the bilateral nucleus accumbens in normal rhesus monkey. Neuroreport 2013;24:30–5. 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835c16e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li N, Wang J, Wang X-lian, et al. . Nucleus accumbens surgery for addiction. World Neurosurg 2013;80(3-4):S28.e9–19. 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilden JA, Qing KY, Hauser SR, et al. . Reduced ethanol consumption by alcohol-preferring (P) rats following pharmacological silencing and deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurosurg 2014;120:997–1005. 10.3171/2013.12.JNS13205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coenen VA, Panksepp J, Hurwitz TA, et al. . Human medial forebrain bundle (MFB) and anterior thalamic radiation (ATR): imaging of two major subcortical pathways and the dynamic balance of opposite affects in understanding depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;24:223–36. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11080180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levy D, Shabat-Simon M, Shalev U, et al. . Repeated electrical stimulation of reward-related brain regions affects cocaine but not “natural” reinforcement. J Neurosci 2007;27:14179–89. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4477-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cleva RM, Watterson LR, Johnson MA, et al. . Differential modulation of thresholds for intracranial self-stimulation by mGlu5 positive and negative allosteric modulators: implications for effects on drug self-administration. Front Pharmacol 2012;2:93 10.3389/fphar.2011.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carter A, Hall W. Proposals to trial deep brain stimulation to treat addiction are premature. Addiction 2011;106:235–7. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang TR, Moosa S, Dallapiazza RF, et al. . Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of drug addiction. Neurosurg Focus 2018;45:E11 10.3171/2018.5.FOCUS18163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martínez-Rivera FJ, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Lloret-Torres ME, et al. . Bidirectional modulation of extinction of drug seeking by deep brain stimulation of the ventral striatum. Biol Psychiatry 2016;80:682–90. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ge S, Geng X, Wang X, et al. . Oscillatory local field potentials of the nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule in heroin addicts. Clin Neurophysiol 2018;129:1242–53. 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ge S, Chang C, Adler JR, et al. . Long-term changes in the personality and psychopathological profile of opiate addicts after nucleus accumbens ablative surgery are associated with treatment outcome. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2013;91:30–44. 10.1159/000343199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao HK, Chang CW, Geng N, et al. . Associations between personality changes and nucleus accumbens ablation in opioid addicts. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2012;33:588–93. 10.1038/aps.2012.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Creed M, Pascoli VJ, Lüscher C. Addiction therapy. Refining deep brain stimulation to emulate optogenetic treatment of synaptic pathology. Science 2015;347:659–64. 10.1126/science.1260776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pierce RC, Vassoler FM. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of addiction: basic and clinical studies and potential mechanisms of action. Psychopharmacology 2013;229:487–91. 10.1007/s00213-013-3214-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Helmreich I, Wagner S, Mergl R, et al. . The Inventory Of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C(28)) is more sensitive to changes in depressive symptomatology than the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD(17)) in patients with mild major, minor or subsyndromal depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;261:357–67. 10.1007/s00406-010-0175-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Donzuso G, Cerasa A, Gioia MC, et al. . The neuroanatomical correlates of anxiety in a healthy population: differences between the state-trait anxiety inventory and the hamilton anxiety rating scale. Brain Behav 2014;4:504–14. 10.1002/brb3.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bruss GS, Gruenberg AM, Goldstein RD, et al. . Hamilton anxiety rating scale interview guide: joint interview and test-retest methods for interrater reliability. Psychiatry Res 1994;53:191–202. 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bush AL, Armento ME, Weiss BJ, et al. . The Pittsburgh sleep quality index in older primary care patients with generalized anxiety disorder: psychometrics and outcomes following cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatry Res 2012;199:24–30. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aloba OO, Adewuya AO, Ola BA, et al. . Validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) among Nigerian university students. Sleep Med 2007;8:266–70. 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Korte KJ, Capron DW, Zvolensky M, et al. . The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: do revisions in the item scoring enhance the psychometric properties? Addict Behav 2013;38:1757–63. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fidler JA, Shahab L, West R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: comparison with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence and its components. Addiction 2011;106:631–8. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giltaij HP, Sterkenburg PS, Schuengel C. Psychiatric diagnostic screening of social maladaptive behaviour in children with mild intellectual disability: differentiating disordered attachment and pervasive developmental disorder behaviour. J Intellect Disabil Res 2015;59:138–49. 10.1111/jir.12079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klijn P, Legemaat M, Beelen A, et al. . Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Dutch version of the London Chest activity of daily living scale in patients with severe COPD. Medicine 2015;94:e2191 10.1097/MD.0000000000002191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Okazaki H, Sonoda S, Suzuki T, et al. . Evaluation of use of the medical outcome study 36-item short form health survey and cognition in patients with stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;17:276–80. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mao WC, Chen LF, Chi CH, et al. . Traditional Chinese version of the Mayer Salovey Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT-TC): its validation and application to schizophrenic individuals. Psychiatry Res 2016;243:61–70. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen H, Hao W, Yang D. The development of protracted withdrawal symptoms of opiate dependence. Chinese journal of mental health 2003;17:294–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang C, Li D, Jin H, et al. . Target-specific deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disease. Ann Transl Med 2017;5:402 10.21037/atm.2017.07.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen L, Li N, Ge S, et al. . Long-term results after deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule for preventing heroin relapse: An open-label pilot study. Brain Stimul 2019;12:175–83. 10.1016/j.brs.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amato L, Davoli M, Minozzi S, et al. . Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD003409 10.1002/14651858.CD003409.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.