Abstract

Objectives

To assess a targeted ‘therapy as required’ model of post-discharge outpatient physiotherapy provision. Specifically, we investigated what proportion of patients accessed post-discharge physiotherapy following total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA), whether accessing therapy was associated with post-arthroplasty patient reported outcomes and whether it was possible to predict which patients would access post-discharge physiotherapy from pre-operative data.

Design

Prospective, observational, longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

Single National Health Service orthopaedic teaching hospital in the UK.

Participants

1395 patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty and 1374 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Self-reported access of post-discharge physiotherapy, the Oxford Hip or Knee Score, EuroQol 5-dimension questionnaire and post-operative surgical episode satisfaction metric.

Results

662 (48.2%) patients with TKA and 493 (35.3%) patients with THA accessed additional post-discharge physiotherapy. Patient-reported outcomes (p<0.001) and surgical episode satisfaction (p=0.001) in both THA and TKA were higher in patients that did not participate in post-discharge physiotherapy. Regression models using pre-operative symptom burden and demographic data predicted post-discharge therapy access with an accuracy of only 17% greater than chance in patients with THA and 7% greater than chance in patients with TKA.

Conclusions

In a choice-based service model of ‘therapy as required’ following hip and knee arthroplasty only a third of THA and half of TKA patients accessed post-discharge therapy. Patients who did not access physiotherapy reported greater post-operative outcomes. This variation in the need for post-discharge physiotherapy suggests that targeting of rehabilitation may be a cost-effective model, however it was not possible to reliably predict which patients would access post-discharge physiotherapy from pre-operative data.

Keywords: total knee arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty, physiotherapy, outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a relatively large patient cohort of 2769 total hip and knee replacements performed over a 2-year period at a single orthopaedic unit evaluating a consistent and specific delivery model of post-discharge rehabilitation provision.

A particular strength of this study design is the depth of linked demographic and outcomes data available with which to construct the predictive models.

Data relating to access of post-surgical physiotherapy was reported by the patient at 6-months post-operation via a survey tool and is open to responder biases; however, the large sample size somewhat mitigates this issue.

We are not able to determine the referral route by which the patient accessed post-discharge therapy or the specific content of the physiotherapy received.

Introduction

Lower limb osteoarthritis is an extremely common and disabling condition, which may ultimately require surgical intervention. In excess of 90 000 total hip arthroplasties (THAs) and 90 000 total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are performed each year in the UK alone.1 Projections suggest continued increases of surgical volume year on year.2 3 Though joint replacement is effective at reducing pain and improving physical function in patients with end-stage osteoarthritis, a subgroup of patients continue to report dissatisfaction with their post-operative outcome4 5 highlighted by protracted physical impairment6 and activity limitations.7–10

Physiotherapy is thought to be an important component in achieving optimal results following THA or TKA.11 Immediately post-surgery, throughout the inpatient stay, physiotherapy is aimed at encouraging mobilisation and facilitating a safe discharge. Though subsequent post-discharge physiotherapy is often promoted, there is considerable national and international variation in actual therapy provision. Specific rehabilitation protocols are strongly entrenched at individual physiotherapy departments however the wider efficacy of post-operative physiotherapeutic intervention is poorly established.12–18 This uncertainty as to effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions makes it difficult for commissioning organisations, healthcare providers and patients to make decisions as to the role of post-discharge physiotherapy following total joint arthroplasty and in determining the correct level and mechanism of funding for such services. As a result, there is substantial variety in the delivery and content of post-operative physiotherapy following joint arthroplasty across the UK.

The purpose of this study was to explore variation in patient access of physiotherapy following THA and TKA under a choice based system. Under this service model, routine post-discharge outpatient physiotherapy is not provided following THA and TKA. Instead, the local standard of care is for patients to undertake prescribed home exercises, with all patients able to access additional outpatient physiotherapy services should they require or wish to do so. Specifically, we investigated what proportion of patients accessed post-discharge physiotherapy following THA and TKA, whether accessing therapy was associated with post-arthroplasty patient reported outcomes and whether it was possible to predict which patients would access post-discharge physiotherapy from pre-operative data.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a prospective observational cohort study. All patients undergoing primary THA and TKA were invited to participate in the study that ran alongside the department’s routine outcomes data collection project. Data collection was through questionnaires administered pre-operatively at hospital clinic appointment (2-weeks prior to surgery) and then via postal review at 6-months post-operatively. Patients were sent forms on the 6-month anniversary of the surgical episode, with a further follow-up sent 2-weeks later if no response was received.

All study participants provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the cohort. Patients undergoing primary unilateral THA or TKA at a single National Health Service teaching hospital were prospectively assessed over a 32-month period between January 2013 and September 2015.

The study centre is the only hospital receiving adult referrals for a predominantly urban regional population of approximately 850 000 people. Surgery was carried out by 12 consultant orthopaedic surgeons and their supervised trainees. Local protocols were followed for all aspects of pre-operative, inpatient and post-operative care.

Pre-operatively, a booklet was provided to patients with information about the procedure (THA or TKA) which included detail on rehabilitation, advising as to activity and highlighting exercises to perform. Immediate post-operative therapy (inpatient stay) was protocol driven focussing on knee range of movement, muscle re-education and mobilising with appropriate walking aids to facilitate a safe discharge. Post-discharge practice at the study centre is to promote continued performance of the exercises learned and to provide outpatient physiotherapy as required. As such, patients were referred to outpatient physiotherapy based on clinically assessed need at time of discharge or at 6-week post-surgery clinical review, with additional referral routes available to the patient through general practice services and a national patient self-referral telephone triage system.

Demographic data was obtained for the patient’s age, sex, BMI and socioeconomic denominators using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). The SIMD is a national statistic based on postcode. It combines data on 38 indicators across seven domains, namely, income, employment, health, education, skills and training, housing, geographic access and crime. We applied the 2012 SIMD national data set and report quintiles (from least deprived to most deprived; the fifth quintile representing the most deprived patients). We employed the ‘datazone’ approach where quintile cut-points are identified based on the potential scores in the national SIMD data set as opposed to reporting quintile distributions calculated from the population in question. Physical outcomes were assessed with the Oxford Hip Score (OHS) or Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and EuroQol- 5 Dimension (EQ-5D) questionnaire. Both questionnaires have been thoroughly validated and are the national statistics of choice in the UK for measuring arthroplasty outcomes.

Outcome measures

The OHS and OKS each consist of 12 questions assessing the patient’s pain and function.19 20 Each item is answered on a 5-point response scale ranging from 0 to 4, generating a summed total score ranging from 0 to 48, where 0 indicates the worst possible outcome and 48 good joint function.

The EQ-5D is a standardised instrument with five items covering mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort as well as anxiety and depression.21 As a measure of self-reported general health, it is applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments and provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. Lower scores represent a worse health state. We applied the most commonly used EQ-5D-3L version, where there are three possible responses to the five questions.

Patient surgical episode satisfaction was assessed using a five-point Likert response format at 6-months post-surgery. Patients were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with their operated hip or knee (response options: very satisfied, satisfied, unsure, dissatisfied or very dissatisfied). Self-report of physiotherapy attendance was recorded at 6-month assessment.

Patient and public involvement

There was no specific patient involvement in the design or conduct of the study methodology; however, the study question as to the role of physiotherapy in the post-operative period following joint arthroplasty was highlighted as a priority area for research by a patient feedback project at the study centre.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS V.21.0.22 Demographic indicators are presented as frequencies or means with SD as a measure of dispersal. Differences between patients who accessed physiotherapy after total joint arthroplasty and those who did not were investigated with t-tests, Χ2 tests and Mann-Whitney U tests as appropriate. Effect sizes for differences in continuous variables are given as Cohen’s d.

To identify predictors of physiotherapy access we used a binary logistic regression model with physiotherapy access as dependent variable and patient characteristics and pre-operative OKS/OHS and EQ-5D as predictors. The predictors were included using a forward selection stepwise model building technique (likelihood ratio) with an entry criterion of alpha=0.05. Model fit is described with percentage of correct classifications and predictors are given as ORs with corresponding 95% CIs. Using this methodology, the chance level of correct classifications is 50% and the model-based classification is compared against this value.

Results

One thousand five hundred and thirty-four patients underwent primary THA and 1503 primary TKA in the study time window. Ninety-seven per cent of cases were coded as being performed for a diagnosis of osteoarthritis (the remaining patients being coded as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis). Survey data was available for 1395 (90.9%) patients who underwent THA and for 1374 (91.4%) patients who underwent TKA. All data was included in the analysis. Patients with THA had a mean age of 67.6±11.8 years and 58.1% were female; patients with TKA had a mean age of 69.7±9.3 years and 56.6% were female. Of this total surgical cohort, 493 (35.3%) patients with THA and 662 (48.2%) patients with TKA accessed post-discharge outpatient physiotherapy.

Total hip arthroplasty

Patients with THA accessing post-discharge physiotherapy were younger (64.9 vs 69.1 years, p<0.001) and more likely to be female (p<0.001); however, there were no differences in BMI (p=0.788) or social deprivation index (p=0.438) between the groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and outcome data for patients with THA by post-discharge physiotherapy access

| Referred for physiotherapy | Yes | No | Effect size | Statistic | Significance |

| Sex N (%) | |||||

| Female | 324 (65.7) | 486 (53.9) | Χ2=218.352 | P<0.001* | |

| Male | 169 (34.3) | 416 (46.1) | |||

| Side N (%) | |||||

| Left | 212 (43.5) | 422 (47.6) | Χ2=22.123 | P=0.157* | |

| Right | 275 (56.5) | 464 (52.4) | |||

| SIMD | |||||

| First quintile N (%) | 37 (7.5) | 76 (8.4) | Z=−0.78 | P=0.438† | |

| Second quintile N (%) | 78 (15.8) | 160 (17.7) | |||

| Third quintile N (%) | 85 (17.2) | 166 (18.4) | |||

| Fourth quintile N (%) | 129 (26.2) | 193 (21.4) | |||

| Fifth quintile N (%) | 164 (33.3) | 307 (34.0) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.9 (13.2) | 69.1 (10.6) | 0.35§ | T=−6.08 | P<0.001‡ |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.3 (6.9) | 28.2 (5.0) | 0.02§ | T=0.27 | P=0.788‡ |

| OHS | |||||

| Preoperative | 20.1 (8.6) | 21.4 (8.6) | 1.31§ | T=−2.67 | P=0.008‡ |

| Post-operative | 35.8 (9.8) | 39.4 (8.6) | 0.39§ | T=−6.96 | P<0.001‡ |

| Change | 15.6 (10.6) | 18.0 (9.9) | 0.23§ | T=−4.06 | P<0.001‡ |

| EQ-5D | |||||

| Preoperative | 0.35 (0.3) | 0.41 (0.3) | 0.20§ | T=−2.92 | P=0.004‡ |

| Post-operative | 0.70 (0.3) | 0.80 (0.2) | 0.39§ | T=−6.52 | P<0.001‡ |

| Change | 0.35 (0.4) | 0.39 (0.3) | 0.12§ | T=−2.28 | P=0.023‡ |

| Satisfaction | |||||

| Very satisfied | 280 (57.4) | 648 (73.3) | Z=−6.43 | P<0.001† | |

| Satisfied | 122 (25.0) | 165 (18.7) | |||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 44 (9.0) | 43 (4.9) | |||

| Dissatisfied | 27 (5.5) | 13 (1.5) | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 15 (3.1) | 15 (1.7) | |||

*Χ2.

†Mann-Whitney U test.

‡t-test.

§Cohen’s d.

BMI, body mass index; EQ-5D; EuroQol 5-Dimension; OKS, Oxford Hip Score (OKS); SIMD, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

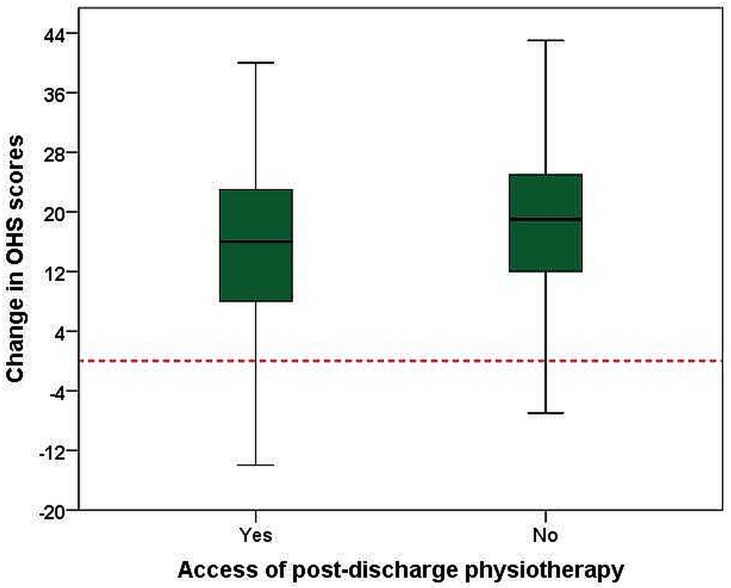

Patient outcomes were superior in the 64.7% of patients who did not access post-discharge physiotherapy in terms of absolute OHS (39.4±8.6 vs 35.8±9.8, p<0.001). At baseline, patients who accessed post-discharge physiotherapy reported modestly, but statistically, lower scores (20.1±8.6) than patients who did not (21.4±8.6) on the OHS (p=0.008). However, patients who did not access physiotherapy made a larger gain in pain and function scores with the OHS: improvement from baseline to 6-months follow-up was 15.6±10.6 points without post-discharge physiotherapy access and 18.0±9.9 points for those that did (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.23) (table 1 and figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in Oxford Hip Scores (OHS) by post-operative physiotherapy access in patients with total hip arthroplasty.

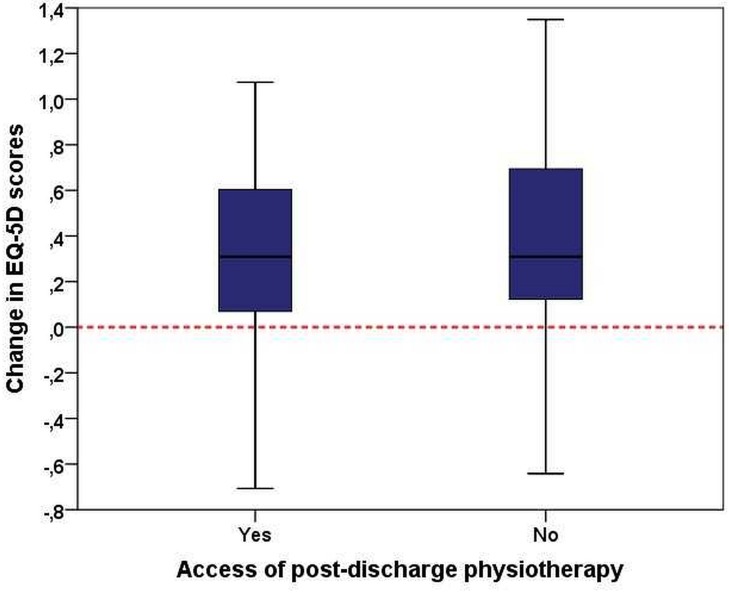

EQ-5D scores were lower in patients accessing post-discharge physiotherapy both pre-surgery (0.35 vs 0.41, p=0.004) and post-surgery (0.70 vs 0.80, p<0.001). Cohen’s d for pre-operative and post-operative improvement was 0.12 with mean changes in EQ-5D score of 0.35 in those that accessed physiotherapy compared with 0.39 in those that did not (p=0.023) (table 1 and figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change in EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) scores by post-operative physiotherapy access in patients with total hip arthroplasty.

The patients who did not access post-operative physiotherapy reported greater surgical episode satisfaction at 6-months (p<0.001, Z=−6.43), twice the number of patients reporting either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied were observed in the group that accessed physiotherapy (table 1).

Total knee arthroplasty

Patients with TKA accessing post-discharge physiotherapy were modestly but significantly younger (68.2 vs 71.0 years, p<0.001). There was no difference in sex (p=0.099). Patients who accessed physiotherapy were more likely to live in a less deprived area (p=0.028); there was no difference in BMI between groups (p=0.198) (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and outcomes data for patients with TKA by post-discharge physiotherapy access

| Referred for physiotherapy | Yes | No | Effect size | Statistic | Significance |

| Sex N (%) | |||||

| Female | 390 (58.9) | 388 (54.5) | Χ2=22.726 | P=0.099* | |

| Male | 272 (41.1) | 324 (45.5) | |||

| Side N (%) | |||||

| Left | 321 (49.5) | 337 (47.7) | Χ2=20.404 | P=0.525* | |

| Right | 328 (50.5) | 369 (52.3) | |||

| SIMD | |||||

| First quintile N (%) | 63 (9.5) | 66 (9.3) | Z=−2.19 | P=0.028† | |

| Second quintile N (%) | 104 (15.7) | 162 (22.8) | |||

| Third quintile N (%) | 122 (18.4) | 136 (19.1) | |||

| Fourth quintile N (%) | 164 (24.8) | 138 (19.4) | |||

| Fifth quintile N (%) | 209 (31.6) | 210 (29.5) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 68.2 (9.7) | 71.0 (8.6) | 0.30§ | T=−5.73 | P<0.001‡ |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 31.1 (6.0) | 30.6 (5.9) | 0.01§ | T=1.29 | P=0.198‡ |

| OKS | |||||

| Preoperative | 20.9 (7.8) | 20.9 (7.9) | <0.01§ | T=−0.04 | P=0.965‡ |

| Post-operative | 32.3 (9.8) | 35.9 (9.1) | 0.38§ | T=−6.99 | P<0.001‡ |

| Improvement | 11.4 (9.4) | 15.0 (8.9) | 0.39§ | T=−7.16 | P<0.001‡ |

| EQ-5D | |||||

| Preoperative | 0.43 (0.3) | 0.41 (0.3) | 0.07§ | T=1.33 | P=0.183‡ |

| Post-operative | 0.68 (0.3) | 0.77 (0.2) | 0.35§ | T=−6.34 | P<0.001‡ |

| Improvement | 0.25 (0.3) | 0.35 (0.3) | 0.32§ | T=−6.15 | P<0.001‡ |

| Satisfaction, N (%) | |||||

| Very satisfied | 271 (41.6) | 427 (61.3) | Z=−8.22 | P<0.001† | |

| Satisfied | 214 (32.8) | 198 (28.4) | |||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 98 (15.0) | 43 (6.2) | |||

| Dissatisfied | 51 (7.8) | 20 (2.9) | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 18 (2.8) | 9 (1.3) | |||

*Χ2.

†Mann-Whitney U.

‡t-test.

§Cohen’s d.

BMI, body mass index; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimension; OKS, Oxford Knee Score; SIMD, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

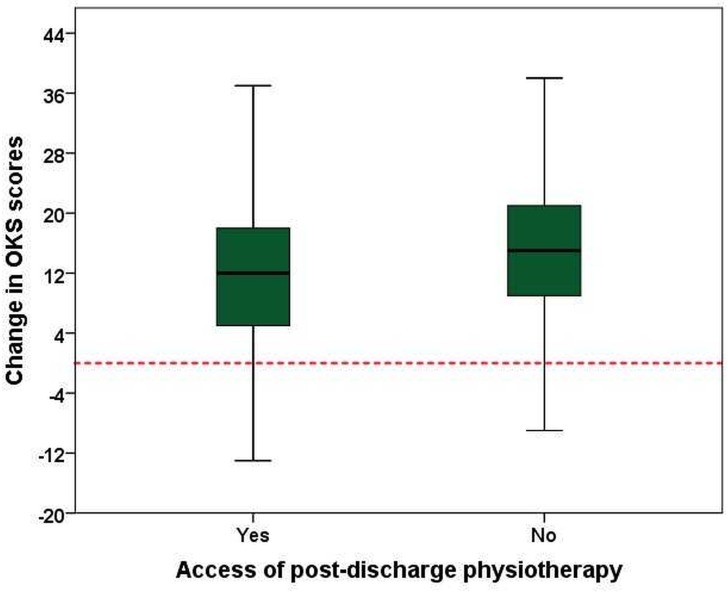

Patient outcomes were superior in the 51.8% of patients with TKA who did not access post-discharge physiotherapy in terms of absolute OKS (35.9 vs 32.3 points, p<0.001). There was no difference in pre-operative score between groups (20.9 points in each group, p=0.965), reflected in a lesser change in OKS for the patients who accessed post-discharge physiotherapy (11.4 points vs 15.0 points, p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.39) (table 2 and figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in Oxford Knee Scores (OKS) by post-operative physiotherapy access in patients with total knee arthroplasty.

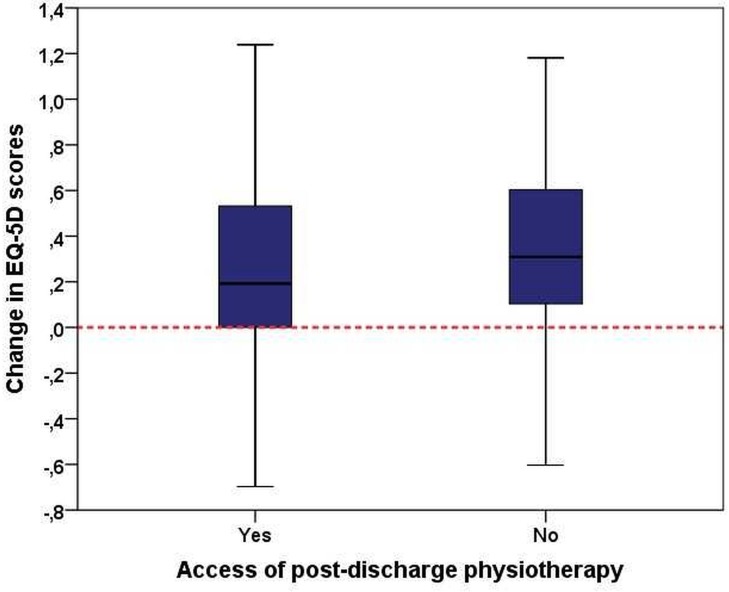

There were also differences in improvement measured with the EQ-5D (table 2). Patients accessing post-discharge physiotherapy improved 0.25 points, compared with 0.35 points in those who did not (p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.32, figure 4). Again there was no difference in pre-operative scores between groups (0.43 vs 0.41, p=0.183), while post-operative scores differed significantly (0.68 vs 0.77, p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Change in EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) scores by post-operative physiotherapy access in patients with total knee arthroplasty.

The patients who did not access post-operative physiotherapy reported greater surgical episode satisfaction (p<0.001, Z=−8.22), with twice the number of patients dissatisfied and very dissatisfied in the group that accessed post-discharge physiotherapy (table 2).

Multivariate analysis

Binary logistic regression modelling was undertaken to determine if post-operative access to physiotherapy could be predicted by pre-operative patient variables. A regression model with three predictors (age, sex and pre-operative EQ-5D score) was able to correctly classify 66.9% of patients with THA in regard to post-operative physiotherapy access (table 3). This percentage of correct classifications was significantly (p<0.001) different from chance (50% correct classifications). In patients with TKA, the regression model comprised only two significant predictors (age and sex) and provided a percentage of correct classifications of 57.4%, again significantly better than chance (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Predictive accuracy of demographic and preoperative outcome parameters for patients accessing post-discharge physiotherapy

| THA | TKA | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | Correct classifications | OR | 95% CI | P value | Correct classifications | |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.04 | <0.001 | 66.9% | 1.04 | 1.02 to 1.05 | <0.001 | 57.4% |

| Sex | 1.60 | 1.27 to 2.03 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.01 to 1.58 | 0.038 | ||

| EQ-5D | 1.54 | 1.08 to 1.20 | 0.018 | – | – | – | – | |

EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimension; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Discussion

There is no consensus as to how best to rehabilitate patients following THA or TKA. Systematic reviews of post-operative rehabilitation interventions suggest that no one approach is beneficial in improving outcomes8 16 18 and a recent Cochrane review stressed the general low quality of the evidence base.23 In this study, we review an ‘access physiotherapy as needed’ model of post-discharge service delivery. Routine outpatient physiotherapy was not provided following THA and TKA. Instead, the local standard of care was for patients to undertake prescribed home exercises, with all patients able to access additional outpatient physiotherapy should they require or wish to do so. Under this system, patients can be referred to physiotherapy based on clinical need as determined by clinical staff at time of discharge (either inpatient medical or therapy teams), or at 6-week out-patient review (medical, nursing or therapy team performing these post-surgery reviews), or at any point through the patient’s General Practitioner service. Separately, the patient could refer themselves via a telephone triage system or access private physiotherapy self-funded and distinct to physiotherapy provision via the National Health Service.

Under this system, only a third of patients that underwent THA and half of those who underwent TKA accessed post-discharge outpatient physiotherapy to assist with their recovery. The patients that did not access physiotherapy do not seem to have been adversely affected by this decision as this group reported better outcome scores. A difference in pre-operative to post-operative change in Oxford Score of approximately three points was observed between the patients with THA and approximately four points in the patients with TKA that accessed physiotherapy compared with those that did not. The minimal clinically important difference in Oxford Scores has been estimated at five points24 in THA and four points in TKA, suggesting the statistical differences reported in the patients with THA are unlikely to reflect a clinically meaningful difference, but that the TKA data may represent variation in clinical outcomes between groups.

The Oxford Scores, EQ-5D scores and satisfaction scores at 6-months reported by the patients that did not access physiotherapy compare well to national outcome figures for both patients with THA and TKA.25 This suggests that post-discharge physiotherapy is not necessarily required in all cases and that (broadly) patients and clinicians are able to make a judgement as to whether they should attend such therapy.

This is an observational cohort study and we do not attempt to evaluate the effectiveness of physiotherapy with this data. Those who accessed additional therapy in this cohort reported lower scores, suggesting greater physical dysfunction in the early post-operative phase. It may be that the additional therapy improved the patient outcomes compared with having had no such intervention. Patients and clinicians expect a rehabilitation component to be provided as part of the care pathway for joint arthroplasty. Though there is a role for physiotherapy around total joint arthroplasty, it may be that post-discharge physiotherapy should be targeted to those that require additional rehabilitation to optimise outcomes as opposed to blanket provision for all. In this setting, self-directed home exercises appear to have been sufficient for the majority of patients to achieve a good outcome post-arthroplasty. This finding could be explored for cost-effectiveness from the health economic and service delivery perspective, however, relies on accurately targeting physiotherapy to those that require the additional input.

We were able to construct statistically significant regression models using pre-operative data to correctly classify the patients that accessed post-operative therapy, however these models were poor in terms of accuracy. The model describing access of physiotherapy following THA was only 17% greater than chance at correctly identifying individuals. The patients that underwent THA who accessed physiotherapy reported lower general health scores (EQ-5D) but broadly equivalent joint specific pain and function (OHS). The EQ-5D data essentially drove the regression model and perhaps suggests poorer health status may be related to the requirement for additional therapy. These patients were on average 5 years younger, suggesting health and not age is the pertinent factor here. Interestingly, pre-operative pain and functional ability (Oxford Score), BMI and deprivation status did not influence the models.

Notably more patients with TKA required or wished to access additional physiotherapy than THA, which is perhaps consistent with the reports of greater treatment success and patient outcomes following hip arthroplasty.5 26 Despite applying a range of pre-operative demographic and symptom state indicators, we were only able to model the additional use of post-discharge physiotherapy to an accuracy of 7% greater than chance. Interestingly, in the TKA cohort, the model relied solely on small associations with age and sex. In this model, pre-operative pain/function/health scores, social deprivation and BMI did not help determine which patient would go on to require additional therapy.

Though various factors have been associated with poor clinical outcomes following TKA, currently, we cannot reliably predict pre-operatively who will struggle to recover post-operatively. Larger and more comprehensive predictor studies (eg, incorporating psychological variables) are required to determine which patient factors lead to poorer post-operative outcomes and to see if particular patient groups benefit from post-discharge physiotherapy. Further insight may be provided by the multicentre TRIO and COASt studies that are currently evaluating this in the UK.26 27 Alternatively, it may be that it is the patient’s response to surgery as opposed to pre-operative characteristics that determine the need for post-operative rehabilitation and that there is no reliable way to predict this pre-operatively.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the relatively large patient cohort of 2769 arthroplasties and the depth of linked demographic and outcome data. Additionally, that our data is in line with UK national figures for patient demographics and pre-operative and post-operative outcome scores lends wider credibility. Limitations are that the access of post-discharge physiotherapy was documented and reported by the patient at 6-months post-arthroplasty, which open potential responder biases. Further, we are not able to determine the route by which the patient accessed this post-discharge therapy or the content of the specific physiotherapy received. The relatively short post-operative 6-month time frame results that we cannot comment on longitudinal changes in outcomes or whether those patients that access physiotherapy ‘caught-up’ with those that did not in terms of clinical outcome scores at subsequent later time points. The study was not designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the physiotherapy received, however future studies may be able to target therapy to patients deemed ‘at need of intervention’ and randomise to differing levels or modes of intervention.

Conclusion

In a choice-based service model of targeted physiotherapy ‘as required’ following hip and knee arthroplasty only a third of patients with THA and half of the patients with TKA accessed post-discharge physiotherapy. The patients who reported greater post-operative outcome scores and surgical episode satisfaction did not access additional therapy, suggesting a variation in therapy requirement -. We were unable to predict pre-operatively which patients would subsequently access additional therapy input.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: DFH conceived the study, interpreted the results, drafted and revised the manuscript. FCL performed the statistical analysis, drafted the results and contributed to manuscript revisions. DJM obtained the data, collated the data and contributed to manuscript drafting and revision. GMF, DB, HS, JTP and CH contributed to results interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision. JTP, CH contributed to the study design.

Funding: This work was supported by Arthritis Research UK [ref 71000] and an institutional award from Stryker to the University of Edinburgh (ref RB0412). The funders had no role in the study design, collation or analysis of data, interpretation of data nor writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: DFH, DB, GMF and HS, are grant holders on the Arthritis Research UK funded TRIO study.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (11/AL/0079).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data cannot be made publicly available to protect patient confidentiality; however, restricted data may be made available if deemed reasonable by the data custodian. Such requests should be made to CRH via the corresponding author.

References

- 1. National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry for England and Wales: 14th Annual report. 2017.

- 2. Culliford DJ, Maskell J, Kiran A, et al. The lifetime risk of total hip and knee arthroplasty: results from the UK general practice research database. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012;20:519–24. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:780–5. 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, et al. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:893–900. 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamilton DF, Lane JV, Gaston P, et al. Assessing treatment outcomes using a single question: the net promoter score. Bone Joint J 2014. 96-B:622–8. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B5.32434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000435 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McMeeken JM, Galea MP. Impairment of muscle performance before and following total hip replacement. Int J Ther Rehabil 2007;14:55–62. 10.12968/ijtr.2007.14.2.23515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, et al. Recovery of physical functioning after total hip arthroplasty: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Phys Ther 2011;91:615–29. 10.2522/ptj.20100201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McClelland JA, Webster KE, Feller JA. Gait analysis of patients following total knee replacement: a systematic review. Knee 2007;14:253–63. 10.1016/j.knee.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rossi MD, Hasson S, Kohia M, et al. Mobility and perceived function after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2006;21:6–12. 10.1016/j.arth.2005.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Westby MD, Backman CL. Patient and health professional views on rehabilitation practices and outcomes following total hip and knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis:a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:119 10.1186/1472-6963-10-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku LJ, Lj K, et al. Disparities in postacute rehabilitation care for stroke: an analysis of the state inpatient databases. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1220–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naylor J, Harmer A, Fransen M, et al. Status of physiotherapy rehabilitation after total knee replacement in Australia. Physiother Res Int 2006;11:35–47. 10.1002/pri.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lingard EA, Berven S, Katz JN. Kinemax Outcomes Group. Management and care of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: variations across different health care settings. Arthritis Care Res 2000;13:129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roos EM. Effectiveness and practice variation of rehabilitation after joint replacement. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2003;15:160–2. 10.1097/00002281-200303000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Artz N, Elvers KT, Lowe CM, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:15 10.1186/s12891-015-0469-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Dewey ME, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a systematic review of clinical trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:98 10.1186/1471-2474-10-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise after knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2007;335:812 10.1136/bmj.39311.460093.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, et al. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;80:63–9. 10.1302/0301-620X.80B1.7859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, et al. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:185–90. 10.1302/0301-620X.78B2.0780185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. EuroQol Group. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 [program]. Armonk: NY: IBM Corp, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamilton D, Henderson GR, Gaston P, et al. Comparative outcomes of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. Postgrad Med J 2012;88:627–31. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beard DJ, Harris K, Dawson J, et al. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:73–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khan F, Ng L, Gonzalez S, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes following joint replacement at the hip and knee in chronic arthropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2:CD004957 10.1002/14651858.CD004957.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simpson AH, Hamilton DF, Beard DJ, et al. Targeted rehabilitation to improve outcome after total knee replacement (TRIO): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:44 10.1186/1745-6215-15-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arden N, Altman D, Beard D, et al. Lower limb arthroplasty: can we produce a tool to predict outcome and failure, and is it cost-effective? An epidemiological study. Southampton (UK), 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.