Abstract

Objectives

Suspected transient ischaemic attack (TIA) necessitates an urgent neurological consultation and a rapid start of antiplatelet therapy to reduce the risk of early ischaemic stroke following a TIA. Guidelines for general practitioners (GPs) emphasise the urgency to install preventive treatment as soon as possible. We aimed to give a contemporary overview of both patient and physician delay.

Methods

A survey at two rapid-access TIA outpatient clinics in Utrecht, the Netherlands. All patients suspected of TIA were interviewed to assess time delay to diagnosis and treatment, including the time from symptom onset to (1) the first contact with a medical service (patient delay), (2) consultation of the GP and (3) assessment at the TIA outpatient clinic. We used the diagnosis of the consulting neurologist as reference.

Results

Of 93 included patients, 43 (46.2%) received a definite, 13 (14.0%) a probable, 11 (11.8%) a possible and 26 (28.0%) no diagnosis of TIA. The median time from symptom onset to the visit to the TIA service was 114.5 (IQR 44.0–316.6) hours. Median patient delay was 17.5 (IQR 0.8–66.4) hours, with a delay of more than 24 hours in 36 (38.7%) patients. The GP was first contacted in 76 (81.7%) patients, and median time from first contact with the GP practice to the actual GP consultation was 2.8 (0.5–18.5) hours. Median time from GP consultation to TIA service visit was 40.8 (IQR 23.1–140.7) hours. Of the 62 patients naïve to antithrombotic medication who consulted their GP, 27 (43.5%) received antiplatelet therapy.

Conclusions

There is substantial patient and physician delay in the process of getting a confirmed TIA diagnosis, resulting in suboptimal prevention of an early ischaemic stroke.

Keywords: stroke, neurology, organisation of Health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We interviewed patients suspected of transient ischaemic attack (TIA) before the definite diagnosis was established, thus without bias caused by knowledge of the final diagnosis.

We were able to provide precise estimates of the different components of the total pre-hospital delay time.

We also assessed whether antiplatelet therapy was initiated prior to the neurologist’s assessment.

In 11 of 93 cases, we used an expert panel to determine the diagnosis of TIA, in absence of a conclusion of the consulting neurologist.

Our cohort is relatively small, but large enough to provide these estimates of current time delay in patients suspected of TIA.

Introduction

A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is a medical emergency, as the risk of a subsequent ischaemic stroke following a TIA is highest in the early stage. Urgent neurological consultation followed by proper stroke preventive treatment reduces this risk substantially, with the rapid start of an antiplatelet agent as key intervention.1 2

Previous studies indicated that around 30%–40% of patients with TIA delay contacting a medical service for more than 24 hours.1 3–5 Over the past decade, patient awareness campaigns like ‘Act FAST’ aimed for better recognition of and a quick response to symptoms suspected of stroke to enable thrombolysis or invasive treatment within the first hours.6 Although TIA is part of the acute ischaemic brain spectrum, it is uncertain whether campaigns like this also positively affect acting on symptoms that are transient, typically short-lasting and often less distinct. A before and after evaluation of the ‘Act FAST’ showed an improvement of patient delay in stroke patients, but in patients with a TIA or minor stroke there was no improvement in use of emergency medical services or time to first seeking medical attention within 24 hours.7

The EXPRESS study (2007) laid the foundation for a drastic decrease of physician delay to diagnosis and treatment of TIA, (1) by the development of rapid-access TIA servicesand (2) guidelines for general practitioners (GPs).1 8 The Dutch GP guidelines recommend GPs to refer all patients suspected of TIA to a TIA service within 24 hours, and to immediately initiate a platelet aggregation inhibitor, unless it is certain that the patient will be examined by a neurologist on the same day.9 The UK GP guidelines emphasise an immediate start of medication by the GP in any suspected TIA patient, and have recommended the use of the prognostic ABCD2 score (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration, diabetes) to define high-risk patients that have to be examined by the neurologist within 24 hours.10 However in the latest update of the UK national clinical guideline for stroke in 2016, the use of the ABCD2 score was abandoned, since new studies showed that the ABCD2 is an inaccurate predictor of early stroke.11–13 This guideline now also recommends to refer all suspected TIA patients to a TIA service within 24 hours.

We aimed to assess current patient and physician delay from onset of suspected TIA symptoms to specialist consultation.

Methods

We conducted a survey among patients suspected of TIA who were referred to one of two participating rapid-access TIA services in the city of Utrecht, the Netherlands. Availability of TIA services in the Netherlands is restricted to weekdays. During 6 months in the period 2013–2014, consecutive patients were asked to participate when arriving at the TIA service. Patients were excluded in the case of: (1) ongoing symptoms; (2) onset of symptoms in-hospital or outside the Netherlands; (3) severe cognitive impairment and (4) inability to clarify the time of onset of symptoms.

Participants suspected of TIA were interviewed at the start of their day at the TIA service before knowing their final diagnosis. We collected information about the following items in a standardised questionnaire (included as an online supplementary file): (1) the interval from onset of symptoms to the patient’s first contact with a medical service (patient delay), the interval to the GP visit and the interval to the TIA service visit; (2) the initiation of an antiplatelet agent; (3) the type and duration of symptoms; (4) the initial reaction of the patient (what did the patient do?); (5) the initial perception (what did the patient think?) and (6) general knowledge of TIA. Responses were written down by the interviewer. In case a patient had experienced multiple recent (suspected) TIAs, we evaluated the last event.

bmjopen-2018-027161supp001.pdf (74.9KB, pdf)

We considered the consulting neurologist’s diagnosis of TIA as reference. Diagnoses were categorised as definite TIA or minor stroke, probable TIA, possible TIA or no TIA. In 11 cases (11.8%), the neurologist’s conclusion was unclear or absent, and three clinicians (LSD, LJK and FHR) decided in a consensus meeting on the diagnosis.

In this observational study, with estimations of delay, a method for sample size calculation is lacking. We therefore included a convenient number of participants.

Delay is presented as median with 25%–75% IQR. We used Mann-Whitney U tests for comparing delay across subgroups. In an overview of results per interview item, we additionally compared results between those with a definite or probable TIA (or minor stroke), and those with no or a possible TIA, applying χ2 tests.

Patient and public involvement

There were no patients or public involved in the design or conduct of this study.

Results

A total of 103 patients consented to participate. Ten patients were excluded because of: (1) ongoing symptoms (n=3), (2) onset of symptoms in-hospital or abroad (n=2), (3) an unclear onset of symptoms (n=3) and (4) severe cognitive impairment (n=2). Table 1 shows characteristics of the 93 participants. Mean (SD) age was 65.2 (13.4) years and 55 (59.1%) were male. The median time from symptom onset to our interview at the TIA service was 4.8 (IQR 1.8–13.2) days. Table 2 shows an overview of the different parts of time delay to the assessment at the TIA service.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of 93 patients suspected of TIA

| Characteristics | Total |

| (n=93) | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 65.2 (13.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 55 (59.1) |

| Prior TIA/ischaemic stroke, n (%) | 23 (24.7) |

| Living situation, n (%) | |

| Alone | 25 (26.9) |

| With a partner | 66 (71.0) |

| In a nursing home | 2 (2.1) |

| Weekend onset of symptoms, n (%) | 31 (33.3) |

| Symptoms, n (%)* | |

| Motor | 32 (34.4) |

| Sensory | 21 (22.6) |

| Visual | 27 (29.0) |

| Speech | 30 (32.3) |

| Median duration of neurological deficits in hours (25%–75% IQR) | 0.5 (0.1–2.4) |

| Diagnosis, n (%)† | |

| TIA or minor stroke | 43 (46.2) |

| Probably TIA | 13 (14.0) |

| Possibly TIA | 11 (11.8) |

| No TIA (TIA mimic) | 26 (28.0) |

*Patients may have experienced more than one symptom.

†In 11 patients, the definite diagnosis was made by a panel consisting of three of the authors.

TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Table 2.

Delay for the 93 patients suspected of a TIA

| Type of delay time | Median time (IQR), hours |

| Patient delay | |

| Time from symptom onset to first contact with medical service | 17.5 (IQR 0.8–66.4) |

| Onset during weekdays (n=31) | 8.8 (IQR 0.5–103.5) |

| Onset during weekend (n=62) | 21.0 (IQR 13.0–65.3) p=0.29 |

| Prior TIA or stroke | 3.0 (IQR 0.8–40.5) |

| No prior TIA or stroke | 19.0 (IQR 1.0–67.5) p=0.29 |

| GP delay | |

| Time from contact with GP to actual GP consultation (n=76) | 2.8 (0.5–18.5) |

| GP during office hours (n=69) | 3.0 (0.5–9.5) |

| GP out of hours service (n=7) | 1.4 (0.4–7.8) p=0.34 |

| Referral delay | |

| Time from GP consultation to assessment at TIA service (n=76) | 40.8 (IQR 23.1–140.7) |

| GP during office hours (n=69) | 30.5 (IQR 23.2–141.3) |

| GP out of hours service (n=7) | 58.4 (IQR 13.7–96.4) p=0.62 |

| History of TIA/stroke | 105.0 (IQR 27.3–228.8) |

| No history of TIA/stroke | 30.0 (IQR 22.5–98.5) p=0.09 |

| Total delay | |

| Time from symptom onset to assessment at TIA service | 114.5 (IQR 44.0–316.6) |

GP, general practitioner; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Patient delay

The median delay from symptoms to the first contact with a medical service was 17.5 (IQR 0.8–66.4) hours and did not differ significantly between patients with definite or probable TIA/minor stroke (19.0 [IQR 0.9–63.2] hours) and those with possible or no TIA (16.6 [IQR 0.7–92.4] hours). Thirty-six (38.7%) patients delayed seeking medical help for more than 24 hours. In 76 (81.7%) patients, the GP was the first contacted healthcare provider; in 7/76 (9.2%) during out of office hours. The emergency department or ambulance service was contacted directly by seven patients (7.5%) and ten patients (10.8%) first reported their symptoms to a medical specialist (other than a neurologist) via an outpatient clinic. In total, four (4.3%) patients had experienced similar symptoms in the previous three months, however, without contacting a healthcare provider.

In the 31 (33.3%) patients with symptom initiation during the weekend patient delay was 21.0 (IQR 13.0–65.3) hours, and 8.8 (IQR 0.5–103.5) hours in those with symptoms during weekdays (p=0.29). Patients who had a prior TIA or stroke (n=23, 24.7%) contacted the GP in 78.3% of cases (during office hours, n=17; GP out of hours service, n=1), and the median delay to first contact was 3.0 (IQR 0.8–40.5) hours, which was lower than in those without prior TIA/stroke; 19.0 (IQR 1.0–67.5) hours, p=0.29.

Delays until consultation at the TIA service

Among the 76 patients who contacted the GP, the median time from onset of symptoms to the actual GP consultation was 25.5 (IQR 4.0–128.0) hours. The (median) GP delay, i.e. the time from the first contact by the patient with the GP practice to the actual GP consultation, was 2.8 (0.5–18.5) hours. The subsequent median time from GP consultation to the consultation at the TIA service (referral delay) was 40.8 (IQR 23.1–140.7) hours.

In the patients who consulted their own GP during office hours (n=69), referral delay was 30.5 (IQR 23.2–141.3); in the patients who (first) consulted a GP out of hours service (n=7) this was 58.4 (IQR 13.7–96.4) hours (p=0.62). The referral delay was 105.0 (IQR 27.3–228.8) hours in the 23 (24.7%) patients who had a prior TIA or stroke, and 30.0 (IQR 22.5–98.5) in those without prior TIA/stroke (p=0.09).

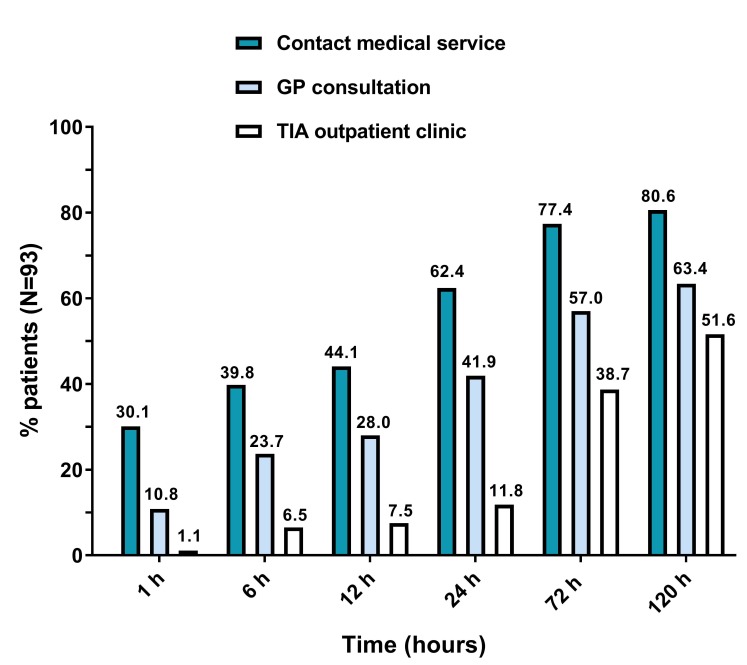

For the complete cohort, the median time from onset of symptoms to the visit to the TIA service was 114.5 (IQR 44.0–316.6) hours. Figure 1 shows the proportions of patients that contacted a medical service, visited the GP, and visited the TIA service, at subsequent points in time from symptom onset.

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients that contacted a medical service, visited the GP and the TIA outpatient clinic, at subsequent points in time from symptom onset. GP, general practitioner; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Of the 62 patients who were naïve to antithrombotic medication, 27 (43.5%) received a platelet aggregation inhibitor from the GP prior to the TIA service visit. Comparing these 27 patients with the 35 patients that did not receive a platelet inhibitor, both the delay from GP to the neurologist’s assessment (32.7 [22.1–94.6] vs 30.0 [22.3–141.0] hours) and the distribution of definite diagnoses (8/27 [29.6%] vs 10/35 [28.6%] diagnosed as no TIA) were similar.

Initial patient’s response and perception of symptoms

Data on the initial response, perception of symptoms and the (general) knowledge of TIA are summarised in table 3. Fifty-four (58.1%) patients initially decided to ‘wait and see’. Sixty-five patients (69.9%) did not call for medical help within the first hour after symptom onset. The main reasons for not calling were disappearance of symptoms (27/65, 42.4%), and not considering the symptoms to be threatening (15/65, 23.4%).

Table 3.

Initial response, perception of symptoms and general knowledge of TIA, in 93 patients suspected of TIA, divided in those with a certain or probably TIA/minor stroke, and in those with no or possibly TIA according to the neurologist*

| Interview item | Total | Certain or probably TIA/minor stroke | No or possibly TIA/minor stroke |

| (n=93) | (n=48) | (n=34) | |

| n (%) | n (%)* | n (%)* | |

| Initial response to symptoms | |||

| Initial response | |||

| Wait and see | 54 (58.1) | 27 (56.3) | 20 (58.8) |

| Direct call to healthcare provider | 18 (19.4) | 8 (16.7) | 6 (17.7) |

| Asking a relative for advice | 17 (18.3) | 10 (20.8) | 7 (20.6) |

| Other | 4 (4.4) | 3 (6.2) | 1 (2.9) |

| Reasons for not seeking medical attention within 1 hour (n=65) | |||

| Symptoms had disappeared | 27 (41.5) | 15 (45.5) | 10 (41.7) |

| Symptoms not considered as threatening | 15 (23.1) | 8 (24.2) | 6 (25.0) |

| Convinced that symptoms would resolve spontaneously | 9 (13.8) | 4 (12.1) | 3 (12.5) |

| Because it occurred during out of office hours | 4 (6.2) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (4.2) |

| Other | 10 (15.4) | 4 (12.1) | 4 (16.6) |

| Perception of symptoms | |||

| Interpreted as an emergency | 30 (32.3) | 17 (35.4) | 8 (23.5) |

| Considered a TIA as possible cause | 37 (39.8) | 16 (33.3) | 14 (41.2) |

| Experienced severity of symptoms on a scale from 0 to 10 (n=90) | |||

| 1–4 | 32 (35.6) | 15 (32.6) | 16 (48.5) |

| 5–7 | 35 (38.9) | 20 (43.5) | 9 (27.3) |

| 8–10 | 23 (25.5) | 11 (23.9) | 8 (24.2) |

| Knowledge of TIA | |||

| Ever heard of a TIA | 76 (87.1) | 35 (72.9) | 30 (88.2) |

| Correctly knowing key TIA symptoms | 63 (57.0) | 24 (50.0) | 20 (58.8) |

| Considers rapid treatment (within 24 hours) necessary | 54 (58.1) | 25 (52.1) | 22 (64.7) |

| Knows that TIA may be a precursor of stroke | 44 (47.3) | 22 (45.8) | 17 (50.0) |

*No significant differences between the ‘certain or probable TIA/minor stroke’ patients and ‘no or possible TIA’ patients were found, applying χ2 tests.

†In 11 patients a definite neurologist’s diagnosis could not be retrieved from the medical files.

TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Thirty (32.3%) patients interpreted their symptoms as a medical emergency. Asking about initial thoughts on the possible cause of their symptoms, 65 (60.2%) did not consider a TIA. Most patients were familiar with the medical term TIA (76/93, 87.1%), but 40 (43.0%) patients had no or an incorrect idea about the symptoms related to TIA.

Discussion

The majority of patients with symptoms suspected of a TIA in this outpatient population delayed seeking medical help, resulting in a delay of more than 24 hours in 38.7% of patients (median 17.5 [IQR 0.8–66.4]). Although the actual GP consultation took place after a median of only 2.8 (0.5–18.5) hours from the first contact with the GP practice (GP delay), it took another 40.8 (IQR 23.1–140.7) hours before the patient was seen at the TIA clinic (referral delay). Only a minority (43.5%) of patients naïve to antithrombotic medication received an antiplatelet agent from the GP prior to the assessment by the neurologist.

The extent of patient delay in our study corresponds with the delay reported in previous studies from the UK, published between 2006 and 2016.1 3–5 14 15 Both the Dutch and British healthcare systems have a strong primary care system and rapid-access TIA services. In the Netherlands, there have been campaigns promoting recognition of stroke symptoms similar to the UK ‘Act FAST’ campaign. Our results indicate that during the last decade no clear reduction in patient delay was achieved, despite these campaigns explaining the most important stroke symptoms and stressing its urgency. As in the UK studies, we found that a majority of patients or their relatives do not respond (directly) to transient symptoms that could be caused by brain ischaemia. The disappearance of symptoms was the main reason for delay, followed by considering the symptoms as not threatening. Even though most participants were familiar with the medical term TIA, a minority actually considered the diagnosis.

Given the time from symptom onset to the visit of the rapid-access TIA service, it can be concluded that there is room for improvement of the current Dutch system of TIA management. In everyday practice, the guidelines’ recommendation of an assessment by the neurologist at a rapid-access TIA service the same or next day is not met. The strong gatekeeper’s function of the GPs in the Dutch healthcare system has beneficial effects on selection of referral and health budgets, however, it may also cause undesirable delays in those who actually had a TIA.

Beyond limiting the delay to a complete diagnostic assessment to identify aetiological factors like atrial fibrillation or significant carotid stenosis, probably the most crucial step forward is initiating secondary prevention with antiplatelets in the pre-hospital setting. Recent guidelines clearly recommended immediate initiation of antiplatelets in patients suspected of TIA, but our study shows there is still insufficient awareness among GPs of this requirement: only in 44% of patients with a suspected TIA antiplatelets were initiated. Unlike the UK guidelines that recommend GPs to start such treatment in any suspected TIA patient, the Dutch guidelines recommend GPs to start only if assessment by the neurologist is not feasible the same day. We consider a clear-cut recommendation to start an antiplatelet in any suspected TIA patient (naïve to antithrombotics) as the best option.

If all GPs would follow the recommendation on antiplatelet therapy, the delay time to treatment would only be 2.8 (0.5–18.5) hours. We therefore consider enforcing this recommendation more important than the recommendation on assessment by the neurologist within 24 hours. Our results help to convince GPs that more timely action is needed in patients suspected of TIA.

An alternative care system would be the ‘French’ model with (1) a 24/7 TIA rapid-access service and (2) public campaigns raising awareness among lay people that every acute neurological deficit should be considered a medical emergency similarly to acute chest pain, also requiring ambulance transportation, certainly if symptoms persist (possibly stroke). However, this would mean a large shift in the organisation of healthcare in the Netherlands, a large increase in healthcare costs.

One of the strengths of our study is that we were able to provide precise estimates of the different components of pre-hospital delay. Moreover, we interviewed not only those with definite TIA, but the larger domain of suspected TIA cases, importantly, before the definite diagnosis was established and without bias caused by this knowledge. Recall errors still need to be considered. A limitation was that in 11.8% of cases presence or absence of TIA was determined in consensus by a panel based only on history taking, that is without the conclusion of the consulting neurologist.

Our study indicates that there is still a need for both patient and physician education regarding the required urgency in case of a suspected TIA. Lay people need to be better informed that also mild stroke-like symptoms that quickly disappear have to be reported to a physician as soon as possible. GPs should be better educated about the rationale for an early start of antiplatelet therapy and that they can safely instal this medication. Furthermore, neurologists should advocate the early start of treatment during their contacts with GPs. Further research is needed to explore the main determinants of patient delay and the main reasons for the lack of prescribing antiplatelet therapy by GPs.

Conclusion

Current patient and physician delay in suspected TIA is considerable. Our results emphasise the need for both patient and physician education, aimed at quick consultation at a TIA outpatient clinic and an early start of secondary prevention by GPs in any case of a suspected TIA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LD is a PhD candidate and the primary researcher. LD and FR drafted the manuscript. MB, LK and AW have revised it critically, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The primary researcher (Dr L.S. Dolmans) performed this study as a general practitioner in training, and combined his training with a PhD track. ‘Stichting Beroepsopleiding Huisartsen (SBOH)’, employee of Dutch GP trainees (financially) supported the PhD track.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center of Utrecht, the Netherlands. Formal ethical approval was not required and the committee waived the requirement to obtain formal informed consent. All participants gave their oral consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2007;370:1432–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rothwell PM, Algra A, Chen Z, et al. Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2016;388:365–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30468-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sprigg N, Machili C, Otter ME, et al. A systematic review of delays in seeking medical attention after transient ischaemic attack. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:871–5. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.167924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chandratheva A, Lasserson DS, Geraghty OC, et al. Population-based study of behavior immediately after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke in 1000 consecutive patients: lessons for public education. Stroke 2010;41:1108–14. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson AD, Coleby D, Taub NA, et al. Delay between symptom onset and clinic attendance following TIA and minor stroke: the BEATS study. Age Ageing 2014;43:253–6. 10.1093/ageing/aft144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flynn D, Ford GA, Rodgers H, et al. A time series evaluation of the FAST National Stroke Awareness Campaign in England. PLoS One 2014;9:e104289 10.1371/journal.pone.0104289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolters FJ, Li L, Gutnikov SA, et al. Medical attention seeking after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke before and after the UK Face, Arm, Speech, Time (FAST) Public Education Campaign: results from the Oxford Vascular Study. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:1225–33. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kamal N, Hill MD, Blacquiere DP, et al. Rapid assessment and treatment of transient ischemic attacks and minor stroke in Canadian Emergency Departments: time for a paradigm shift. Stroke 2015;46:2987–90. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verburg AF, Tjon-A-Tsien MR, Verstappen WH, et al. [Summary of the ’Stroke' guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners' (NHG)]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2014;158:A7022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Stroke: national clinical guideline for diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rudd AG, Bowen A, Young GR, et al. The latest national clinical guideline for stroke. Clin Med 2017;17:154–5. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-2-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill MD, Weir NU. Is the ABCD score truly useful? Stroke 2006;37:1636 10.1161/01.STR.0000230125.04355.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perry JJ, Sharma M, Sivilotti ML, et al. Prospective validation of the ABCD2 score for patients in the emergency department with transient ischemic attack. CMAJ 2011;183:1137–45. 10.1503/cmaj.101668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giles MF, Flossman E, Rothwell PM. Patient behavior immediately after transient ischemic attack according to clinical characteristics, perception of the event, and predicted risk of stroke. Stroke 2006;37:1254–60. 10.1161/01.STR.0000217388.57851.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurst K, Lee R, Sideso E, et al. Delays in the presentation to stroke services of patients with transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke. Br J Surg 2016;103:1462–6. 10.1002/bjs.10199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027161supp001.pdf (74.9KB, pdf)