Abstract

Objectives

To compare the costs and effects of higher turnover of resident nurses and Aboriginal health practitioners and higher use of agency-employed nurses in remote primary care (PC) services and quantify associations between staffing patterns and health outcomes in remote PC clinics in the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia.

Design

Observational cohort study, using hospital admission, financial and payroll data for the period 2013–2015.

Setting

53 NT Government run PC clinics in remote communities.

Outcome measures

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were calculated for higher compared with lower turnover and higher compared with lower use of agency-employed nurses. Costs comprised PC, travel and hospitalisation costs. Effect measures were total hospitalisations and years of life lost per 1000 person-months. Multiple regression was performed to investigate associations between overall health costs and turnover rates and use of agency-employed nurses, after adjusting for key confounders.

Results

Higher turnover was associated with significantly higher hospitalisation rates (p<0.001) and higher average health costs (p=0.002) than lower turnover. Lower turnover was always more cost-effective. Average costs were significantly (p<0.001) higher when higher proportions of agency-employed nurses were employed. The probability that lower use of agency-employed nurses was more cost-effective was 0.84. Halving turnover and reducing use of a short-term workforce have the potential to save $32 million annually in the NT.

Conclusion

High turnover of health staff is costly and associated with poorer health outcomes for Aboriginal peoples living in remote communities. High reliance on agency nurses is also very likely to be cost-ineffective. Investment in a coordinated range of workforce strategies that support recruitment and retention of resident nurses and Aboriginal health practitioners in remote clinics is needed to stabilise the workforce, minimise the risks of high staff turnover and over-reliance on agency nurses and thereby significantly reduce expenditure and improve health outcomes.

Keywords: Health Economics, Health Economics, Health Policy, Human Resource Management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data are for an entire population—remote living residents in communities serviced by Northern Territory Department of Health;

Primary care (PC) and secondary care data are linked;

Univariate analyses (calculation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios) are complemented by multiple regression analyses which adjust for key potential confounders;

Analyses included assessing differences in costs and effects that were related to hospital admissions for dialysis and demographic composition of communities (predominantly non-Aboriginal or not);

Effectiveness of PC used proxy measures (hospitalisation rates and years of life lost rates) which may not necessarily best reflect effectiveness of PC.

Introduction

There is an urgent need for high-quality primary care (PC) services for disadvantaged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations (referred to as Aboriginal hereafter) in remote communities of Australia. Australian Aboriginal peoples have higher levels of risk factors for many communicable and non-communicable diseases and experience higher rates of complex acute and chronic diseases such as infectious diseases, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease compared with non-Aboriginal Australians.1–4 The gaps in life expectancy at birth between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal population in the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia in 2009–2013 were 15 and 16 years in males and females, respectively.5 In 2016, 30% of the NT population was Aboriginal and 70% of its Aboriginal population lived in rural and remote areas.6 Australian governments have committed to closing the gap in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians.7

In many remote NT communities, PC is mainly delivered by staff employed directly by the NT Government. In these remote communities, ‘resident’ staff comprise, on average, two nurses or midwives (henceforth called nurses), 0.6 Aboriginal health practitioners (AHPs) and 2.2 other employees all of whom live in the communities on a medium- to long-term basis. Agency-employed nurses provide, on average, 0.4 full-time equivalent (FTE) of additional health manpower per clinic on a short-term, fly-in fly-out basis.8 District medical officers and allied health professionals provide additional professional PC services to patients living in these remote communities through intermittent scheduled visits and telehealth consultations.

Recent research shows that higher utilisation of PC services by Aboriginal people with chronic diseases is cost-effective. Access to, and utilisation of, effective PC, however, may be compromised in remote NT communities by extremely high turnover rates of resident clinical staff and heavy reliance on short-term agency nurses.8–10 Factors previously reported to be associated with nurse turnover in NT include professional, social and geographical isolation, the stressful work environment, unreasonably heavy workloads, lack of support from management and inadequacy of housing.11 NT Government initiatives in the past decade to decrease nurse turnover have included changes to management practices to improve levels of support for nurses, providing increased training and professional development opportunities, increasing the flexibility of employment contracts and restructuring nursing classifications and increasing remuneration.12 13

PC costs per person rise as geographical remoteness of communities increases and population size decreases.14–16 A large proportion of these costs relates to higher staffing costs and costs associated with staff and patients travelling long distances.14 17 Workforce shortages and extremely high staff turnover (averaging 148% per annum for nurses) result in 42% of NT remote area nurses being employed on relatively expensive casual or agency contracts.8 14 16 18

There is a lack of published quantitative evidence, however, of the costs, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different staffing patterns.19 The aims of this research, therefore, are threefold: first, to compare the costs and effects of higher turnover of resident remote area nurses and AHPs with lower turnover; second, to compare the costs and effects of proportionally higher use of agency-employed nurses with lower use of agency-employed nurses and, third, to quantify the effects of nurse and AHP turnover and use of agency-employed nurses on healthcare costs, after adjusting for known confounders.

Methods

Study setting

The study sites were 53 NT Department of Health (DOH) remote health clinics in 46 predominantly Aboriginal communities and seven predominantly non-Aboriginal towns where resident nurses and AHPs provide most clinical PC services. Temporary and ongoing nursing and AHP vacancies were filled by DOH employed casual nurses, DOH employed agency nurses or, as the least preferred, most expensive alternative, by agency-employed nurses (nurses paid directly by nurse employment agencies). In this study, the proportion of agency-employed nurses was used as a marker of overall use of short-term nurses.

Patient involvement

This study comprised analysis of NT DOH secondary data (including individual-level de-identified hospitalisation and PC data). Patients were not directly involved in data provision.

Data

Four NT DOH datasets were used: the Primary Care Information Systems (PCIS), Hospital Inpatients Activity (HIA), Government Accounting System (GAS) and Personnel Information and Payroll Systems (PIPS). The study period was 2013–2015, as this was the most recent period for which the required costs, hospitalisations, ages at death, use of agency-employed nurses and workforce turnover data were available.8

PIPS data were used to calculate turnover rates of Department-employed nurses and AHPs in each month in each clinic (clinic-month):

An exit was defined when a staff member ceased working at a specific remote clinic for a period of at least 12 weeks. A cut-off of 10% differentiated higher (≥10%) from lower (<10%) turnover, equating to 120% annual turnover. Previous research showed that the average annual turnover rate of nurses and AHPs in these remote NT clinics is 128%.20

GAS data were used to calculate PC costs in Australian dollars for each clinic-month. PC clinic costs comprised operational and personnel expenditures and excluded capital expenses. Agency-employed nurse labour expenses were used to derive estimates of aggregated FTE agency-employed nurse use in each clinic-month using a standard NT DOH formula21:

Percentage use of agency-employed nurses in each clinic-month was calculated:

A cut-off of 13% differentiated higher (≥13%) from lower (<13%) use of agency-employed nurses as previous research shows that agency-employed nurse FTEs fill, on average, 13% of nurse positions.8

PCIS data were used to determine the number of PC consultations in each clinic-month. Population catchments (service populations) for each remote clinic were defined as the number of unique patients recorded in PCIS in the previous 12 months.

HIA data were used to determine the community in which each patient lived at the time of hospital admission, to calculate the number of hospitalisations in each clinic-month and to estimate hospitalisation costs using information on diagnoses (Australian Refined Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) codes) provided in discharge summaries22:

Both HIA and PCIS data were used to determine age at death, from which years of life lost (YLLs) were calculated using an age-specific life expectancy table used in the Australian Burden of Disease study.2

Both GAS and PCIS data were used to estimate PC costs in each clinic-month, calculated by first deriving an average consultation cost which was the overall estimated expenditure of the clinic each year divided by the total occasions of service in that year. PC costs per person per month (person-month) were calculated as the average consultation cost multiplied by the number of consultations per person-month. Travel costs were calculated by doubling the straight line distance between the resident community and nearest hospital, based on a flat rate of $2 per kilometre.23

Analyses

Two separate incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated using clinic-month data. In the first analysis (denoted in equations by subscript 1), costs and effects of higher turnover clinic-months were compared with lower turnover rates, whereas in the second analysis (subscript 2) costs and effects of clinic-months with higher use of agency-employed nurses were compared with lower use of agency-employed nurses.

Effects for the respective analyses were calculated as follows:

Total hospitalisation and YLLs rates were used as these measures of benefit in the evaluation were accessible and, having previously been reported in the peer-reviewed cost-effectiveness extant literature in the remote Australian context, were known to be acceptable proxy measures for the effectiveness of PC.

Costs for the respective analyses were calculated as follows:

Costs and effects were measured for each person-month using current expenditure and healthcare data within the short study time frame. No future costs or future health outcomes were considered, nor was discounting considered necessary in this study. The ICER for the first analysis was calculated as the difference in average health costs per 1000 person-months divided by the difference in effects (hospitalisation rates) per 1000 person-months:

The ICER for the second analysis was calculated as the difference in average health costs per 1000 person-months, divided by the difference in effects (YLLs) per 1000 person-months:

Overall hospitalisation rates and YLLs rates were proxies for PC effectiveness in the first and second analyses, respectively. In both the analyses, the perspective of the NT Government was used to identify relevant costs incurred, which included PC, travel and hospitalisation costs per 1000 person-months. A ‘top-down’ approach was used to allocate total remote health expenditure to each clinic, as described elsewhere. All costs were based on actual expenditure.

In addition to calculating ICER point estimates, 2000 bootstrap replicates were used to plot cost-effectiveness planes (mean differences in the cost and effect pairs) and to construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (probability that lower turnover or lower proportional use of agency-employed nurses is cost-effective) to investigate uncertainty. Calculations of ICERs also examined variations in costs and effects if

clinics servicing predominantly non-Aboriginal communities were excluded;

hospitalisations for renal dialysis were excluded and

only potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPHs) were included.24

The average NT cost per hospitalisation of $4213 was used as the benchmark price for a hospitalisation.22 A threshold of $120 000 was used as the benchmark price for a YLL.25

Multiple regression was used to investigate associations between overall costs and nurse and AHP turnover rates and proportional use of agency-employed nurses, after adjusting for key confounders. Potential confounders included Euclidean distance to the nearest hospital, PC consultation rates and hospitalisation rates (both total and PPH).

StataSE V.14 was used for all analyses. A 0.05 level of statistical significance was used.

Results

Between 2013 and 2015, there were 1 266 708 person-months, 46 276 hospital admissions, 2 058 829 PC consultations and a service population of approximately 35 000 persons. Total health costs were $603 million and there were 530 deaths with an estimated 17 750 YLLs.

Higher versus lower turnover

Remote clinic-months with lower staff turnover have both significantly lower total hospitalisation rates (p<0.001) and lower average health cost rates (p=0.002) than higher staff turnover clinic-months (table 1). Analyses for Aboriginal communities only and excluding hospitalisations for renal dialysis revealed similar results; however, analyses of PPHs found lower staff turnover clinic-months were associated with increased costs (p<0.001) and no significant difference in PPHs rate (p=0.430) compared with higher turnover clinic-months.

Table 1.

Average health costs, hospitalisations and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for higher and lower staff turnover, 2013–2015

| Monthly turnover | Total hospitalisations | Excluding predominantly non-Aboriginal communities |

Excluding hospitalisations for renal dialysis |

Potentially preventable hospitalisations | |

| n (person-months) | Higher (≥10%) | 229 968 | 193 328 | 229 968 | 229 968 |

| Lower (<10%) | 1 036 740 | 8 78 406 | 1 036 740 | 1 036 740 | |

| Hospitalisations (per 1000 person-months) | Higher (≥10%) | 45.3 | 51.7 | 17.8 | 2.5 |

| Lower (<10%) | 34.6 | 38.4 | 16.0 | 2.4 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.430 | |

| Average health cost ($) (per 1000 person-months) | Higher (≥10%) | $491 043 | $531 865 | $446 344 | $289 741 |

| Lower (<10%) | $472 826 | $511 977 | $440 355 | $300 740 | |

| P value | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.271 | <0.001 | |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | $1708 | $1500 | $3365 | −$107.830 |

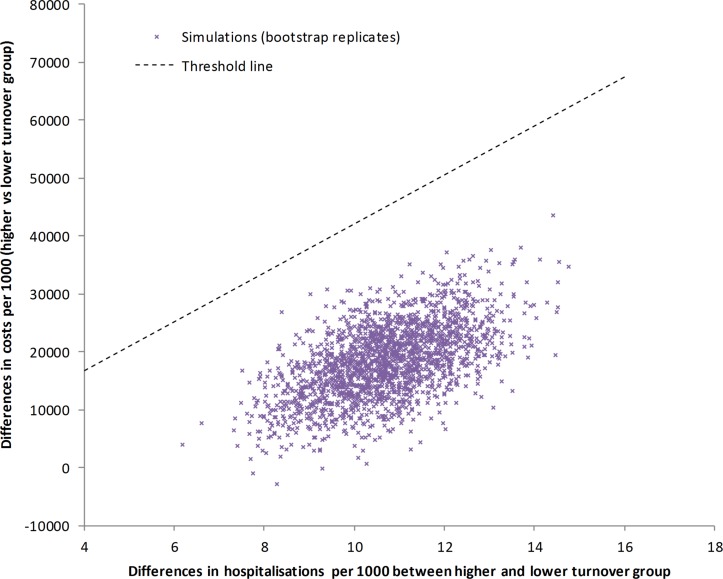

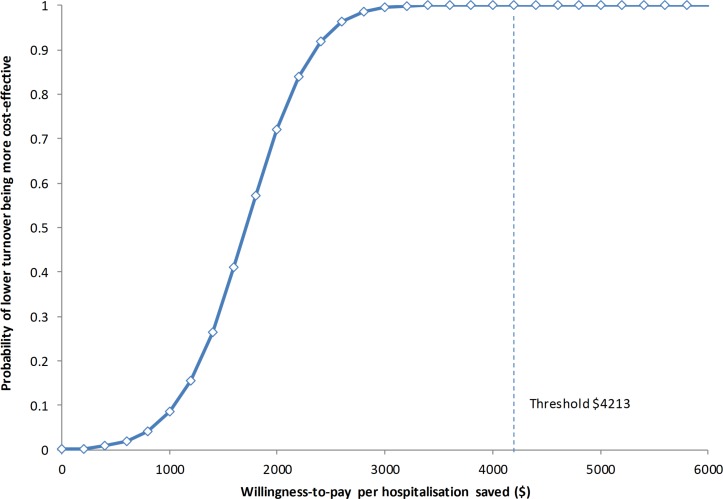

For the analysis of total hospitalisations, the cost-effectiveness plane shows lower turnover was always associated with reduced hospitalisation rates and, in almost all instances, with savings in average healthcare costs compared with higher turnover (figure 1). PC was cost-effective with ICER being $1708 per hospitalisation (savings in both numerator and denominator). At the current NT threshold of $4213 per hospitalisation, the probability of lower turnover being more cost-effective is 1 (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness plane comparing higher (≥10%) with lower (<10%) monthly turnover rates in remote clinics.

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for comparing costs and effects in savings in total health costs between higher (≥10%) and lower (<10%) monthly nurse and Aboriginal health practitioner turnover rates in remote clinics.

Higher versus lower proportional use of agency-employed staff

Remote clinic-months with higher proportional use of agency-employed nurses have both a significantly higher average health cost rate (p<0.001) and higher YLLs rate (p<0.001) than clinic-months with lower use (table 2). Analyses examining variations in effects which excluded predominantly non-Aboriginal communities and excluded renal dialysis hospitalisations confirmed poorer outcomes (greater YLLs rates) in clinic-months with higher proportional use of agency-employed nurses. In remote Aboriginal communities (excluding predominantly non-Aboriginal communities), however, overall costs were higher in clinic-months that had proportionally lower use of agency-employed nurses (p<0.001). PPHs analysis showed no significant differences in YLLs between clinic-months with higher and lower proportional use of agency-employed nurses.

Table 2.

Average health costs, years of life lost and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for higher and lower proportional use of agency-employed nurses, 2013–2015

| Agency nurse proportion | Total | Excluding predominantly non-Aboriginal communities |

Excluding hospitalisations for renal dialysis |

Potentially preventable hospitalisations |

|

| n (person-months) | Higher (≥13%) | 7 04 240 | 6 36 525 | 7 04 240 | 7 04 240 |

| Lower (<13%) | 5 62 468 | 4 35 209 | 5 62 468 | 5 62 468 | |

| YLL (per 1000 person-months) | Higher (≥13%) | 14.6 | 13.7 | 14.6 | 0.0 |

| Lower (<13%) | 13.3 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 0.1 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.978 | |

| Average health cost ($) (per 1000 person-months) | Higher (≥13%) | $480 915 | $503 989 | $446 289 | $301 567 |

| Lower (<13%) | $470 145 | $532 494 | $435 375 | $295 207 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ICER | $7964 | −$29 310 | $8070 | −$70 757 |

ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; YLL, year of life lost.

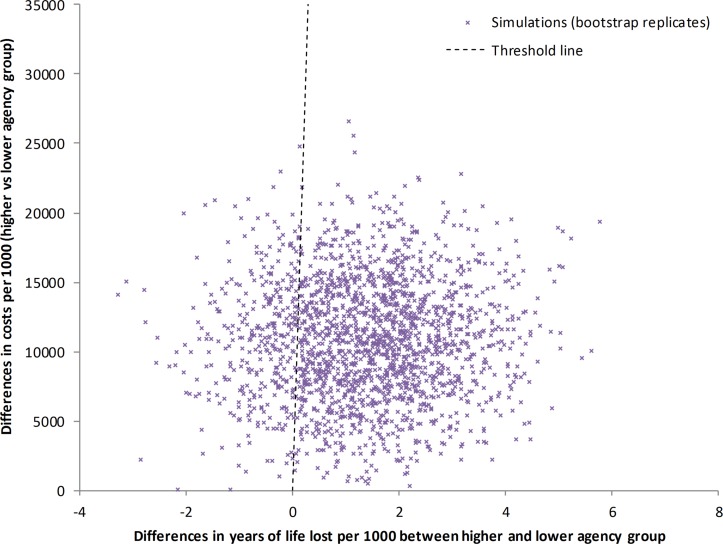

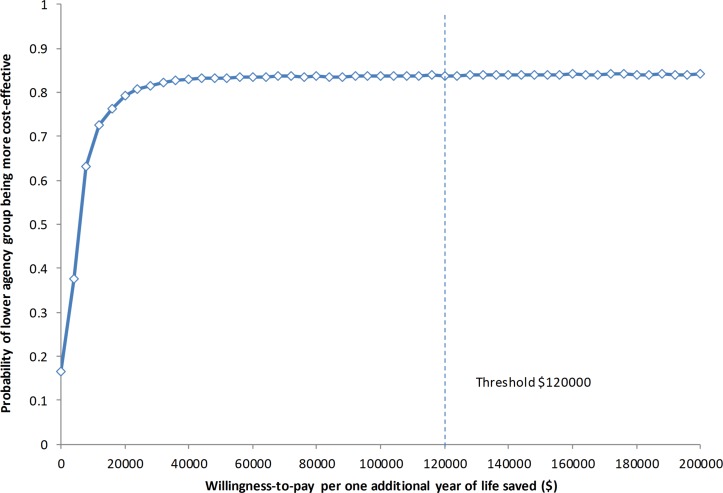

For the analysis of the total study population, lower proportional use of agency nurses was always associated with health cost savings though less strongly associated with fewer YLLs (figure 3). At the threshold value of $120 000 per YLL, the probability of lower use of agency-employed nurses being more cost-effective was 0.838 (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness plane comparing higher (≥10%) with lower (<10%) proportional use of agency-employed nurses in remote clinics.

Figure 4.

Acceptability curve for comparing costs and effects in terms of saving life-years between higher (≥10%) and lower (<10%) proportional use of agency nurses in remote clinics.

Multiple regression modelling of overall cost rates

Overall health cost rates were significantly associated with hospitalisations, PPHs, PC consultations, turnover, use of agency-employed nurses and distance to nearest hospital (table 3). Each 10% increase in annual turnover was associated with an increased cost of $11 per person-month. For each 10% increase in proportion of agency-employed nurses used, there was an associated increase in cost of $10 per person-month. One PPH was associated with an increased cost of $10 063, which was in addition to the costs of a normal hospitalisation. Sensitivity analyses (not shown) revealed similar coefficient estimates.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression model predicting total health costs per person-month

| Coefficient | 95% CI lower limit | 95% CI upper limit | |

| Number of hospitalisations | 2591* | 2584 | 2598 |

| 10% increase in nurse and AHP annual turnover | 11* | 7 | 15 |

| 10% increase in proportional use of agency nurses | 10* | 8 | 11 |

| Potentially preventable hospitalisations | 10063* | 10 001 | 10 126 |

| Euclidean distance to hospital (km) | 0.16* | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| Number of primary care consultations | 170* | 169 | 171 |

*P<0.001.

AHP, Aboriginal health practitioner.

Assuming a service population of 35 000 residents, reducing turnover from 120% per annum to 60% and no longer using agency-employed nurses (reducing from 13% to 0%) results in potential savings of $32 million annually in PC, hospitalisations and travel costs.

Discussion

This landmark empirical study shows that lower nurse and AHP turnover is associated with significantly lower total hospitalisations (p<0.001), lower average health cost rates (p=0.002) and is more cost-effective than higher turnover. The potential savings in healthcare costs of reducing staff turnover are in the order of $32 million annually. Also, lower use of short-term agency nurses has an 84% likelihood of being more cost-effective than higher use.

For Aboriginal communities, PC cost rates were significantly higher in clinic-months that had lower use of agency-employed nurses. This finding was, at face value, counter-intuitive, as agency-employed labour hire is the most expensive staffing option. One possible explanation is confounding of the association by geographical remoteness: the multiple linear regression analysis confirmed that more geographically remote clinics have higher operating costs, consistent with previous research.14 More geographically remote clinics may also be more likely to have lower use of agency nurses and incur even higher costs, for example because agency-employed nurses may be less willing to work in the most geographically remote health services. This research used regression analysis to confirm that healthcare costs in remote PC clinics are positively and significantly associated with hospitalisations (total and PPH), nurse and AHP turnover rates, use of agency-employed nurses, geographical remoteness and the number of PC consultations (table 3).

These are important findings for policymakers and health service managers. The findings suggest that effective investments in workforce strategies that reduce turnover rates and decrease undue reliance on short-term agency nurses may have very significant net benefits, both to the health services’ budgets and to longer-term health outcomes for disadvantaged Aboriginal populations.

This research highlights a pressing need to invest in the systematic implementation of a coordinated range of short- and long-term remote workforce strategies in order to stabilise the workforce, improve continuity of care and thereby improve health outcomes. While our knowledge about the effectiveness of various PC workforce retention interventions is incomplete,26 available evidence suggests that effective short-term retention strategies should be multifaceted and include the following components: necessary infrastructure, including adequate housing, vehicle and communication technologies; offer realistic remuneration, including salary packaging and retention bonuses; ensure organisational effectiveness by (i) strengthening health service and clinic management and leadership, (ii) ensuring comprehensive staff orientation and induction and (iii) maintaining a professional environment through mentoring, ongoing professional development and promoting scholarship; provide appropriate personal and family support for employees; and implement alternative workforce models that are more likely to ensure continuity of care, such as employing nurses to work 1 month on, 1 month off in shared positions.

Longer-term retention strategies, similarly, may best be bundled together and may include the following: providing sufficient funding to ensure an adequate supply of remote health professionals relative to population needs without undue reliance on short-term staff; increased recruitment of, and support for, Aboriginal people to take up clinical and non-clinical roles, which may include the adoption of training models that enable AHP training to be largely based in remote communities; building appropriate training pathways for remote area nurses in partnership with local educational institutions, with a particular focus on appropriate student selection, a contextualised programme and a supported post-graduate employment pathway; and transitioning governance arrangements from NT Government run to Aboriginal community control. While it is not known whether community control of health services is associated with lower health workforce turnover and lower use of short-term agency nurses, we do know that Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services employ a high proportion of Aboriginal staff, and that family connections and a sense of ownership of the service27 contribute to improved access.28 29

This study is not without some limitations. First, estimates of the effects of PC used proxy measures—total hospitalisations and YLL— which may not necessarily best reflect effectiveness of PC. While our analyses extended to investigate variability in results if only PPHs were included, these too have limitations in the context of this study. PPHs comprise <8% of total hospitalisations and the communities in this study were mostly small, so monthly PPHs rates in each remote community have the limitation of increased statistical instability, which may explain the unexpected association between higher proportional use of agency-employed nurses and lower costs. Second, comparison groups for costs and effects were somewhat arbitrarily defined based on clinic-month rather than individual-level data. It would have been preferable to make comparisons on the basis of use of all agency nurses, not just of agency-employed nurses. However, we were not able to accurately identify DOH-employed agency nurses within the payroll data. Also, there were a small number of non-Aboriginal residents in remote Aboriginal communities. Because the non-Aboriginal residents were predominantly healthy workers, the impacts of non-Aboriginal residents on clinic-month health measures were expected to be minimal. Third, our cost estimates may also be imprecise, as they are dependent on the quality of administrative data on expenditure recorded in GAS and on consultation data recorded in PCIS. Fourth, our study also did not include effects of any policy measures designed to reduce staff turnover, nor did it attempt to measure the costs of introducing such policies. While the findings of our study are likely generalisable to other PC clinics in remote, predominantly Aboriginal communities in Australia, caution is advised in generalising beyond these limits. This is an observational study comparing two different situations (higher vs lower turnover; higher vs lower proportional use of agency-employed nurses) using existing administrative data. It is indicative of two simple workforce policy scenarios in which cost-effectiveness information is otherwise lacking. No evidence synthesis and decision modelling were undertaken in this study.

Despite its limitations, the findings of this research provide critically important evidence for policymakers seeking to improve health outcomes for Aboriginal people living in remote Australia while responsibly managing finite health budgets. There is great potential for more cost-effective PC to be attained. This will require PC workforce turnover, retention and use of short-term agency-employed nurses to be addressed as a priority.

Conclusion

Higher turnover of government-employed nurses and AHPs is costly and associated with poorer health outcomes for Aboriginal people. Halving the current annual turnover rate to 60% and reducing the use of agency-employed nurses have the potential to reduce costs to the NT health system by $32 million each year. Systemic investment in a range of coordinated workforce strategies is needed to stabilise the remote workforce, save money, improve Aboriginal health outcomes and ‘close the gap’.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Northern Territory (NT) Department of Health staff who provided technical assistance in accessing and interpreting NT Department of Health personnel, primary care, hospitalisation and financial data. The authors also acknowledge and sincerely thank all staff working in the 53 remote NT communities, particularly the clinic managers. Finally, the authors would acknowledge the contributions of Terry Dunbar, Lisa Bourke, Lorna Murakami-Gold, Tim Carey and David Lyle to the bigger overarching research project and for comments that strengthened this manuscript.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: YZ contributed to the design of the study and led analysis and drafting of the paper. JW conceived and contributed to design of the overarching study and assisted with drafting the paper. JSH contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study and assisted with drafting the manuscript. MPJ, SG, MR and DJR contributed to the design of the study, particularly the quantitative component, and provided comments on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project number DP150102227). The funder had no input in to the design, conduct and reporting of this analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was received from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (2015-2363).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to identifiability of remote primary care providers and the need to protect their privacy.

Author note: Original protocol for the study: The original protocol for the study is published and available (open access): Wakerman J, Humphreys JS, Bourke L, Dunbar T, Jones M, Carey T, et al. Assessing the impact and cost of short-term health workforce in remote Indigenous communities in Australia: a mixed methods study protocol. JMIR research protocols. 2016;5(4):e135.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015. Cat. no. IHW 147. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: fatal burden of disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2010. Australian Burden of Disease Study series no. 2. Cat. no. BOD 2. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Y, Guthridge S, Magnus A, et al. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust 2004;180:498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vos T, Barker B, Begg S, et al. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: the Indigenous health gap. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:470–7. 10.1093/ije/dyn240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao Y, Zhang X, Foley M, et al. Northern Territory burden of disease study: fatal burden of disease and injury, 2004–2013. Darwin: NT Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian demographic statistics, June 2016. Cat no. 3101.0. Canberra: ABS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Council of Australian Governments. National indigenous reform agreement (Closing the Gap). Canberra: COAG, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Russell DJ, Zhao Y, Guthridge S, et al. Patterns of resident health workforce turnover and retention in remote communities of the Northern Territory of Australia, 2013–2015. Hum Resour Health 2017;15:52 10.1186/s12960-017-0229-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao Y, Russell DJ, Guthridge S, et al. Long-term trends in supply and sustainability of the health workforce in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory of Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:836 10.1186/s12913-017-2803-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burns CB, Clough AR, Currie BJ, et al. Resource requirements to develop a large. remote aboriginal health service: whose responsibility? Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22:133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garnett ST, Coe K, Golebiowska K, et al. Attracting and keeping nursing professionals in an environment of chronic labour shortage: A study of mobility among nurses and midwives in the Northern Territory of Australia. Darwin: Charles Darwin University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anonymous. Nurse turnover rate down but continues to be high. Aust Nurs J 2009;16:10. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anonymous. Nurses accept EBA. Aust Nurs J 2009;16:10. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao Y, Malyon R. Cost drivers of remote clinics: remoteness and population size. Aust Health Rev 2010;34:101–5. 10.1071/AH09685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asthana S, Halliday J. What can rural agencies do to address the additional costs of rural services? A typology of rural service innovation. Health Soc Care Community 2004;12:457–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao Y, Russell DJ, Guthridge S, et al. Cost impact of high staff turnover on primary care in remote Australia. Aust Health Rev 2018. 10.1071/AH17262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGrath P, Holewa H, McGrath Z. Practical problems for Aboriginal palliative care service provision in rural and remote areas: equipment, power and travel issues. Collegian 2007;14:21–6. 10.1016/S1322-7696(08)60561-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doh NTG. Remote area nurse safety: on-call after hours security. Darwin: NT Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayes LJ, O’Brien-Pallas L, Duffield C, et al. Nurse turnover: a literature review - an update. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:887–905. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Russell DJ, Zhao Y, Guthridge S, et al. Patterns of Remote Area Nurse and Aboriginal Health Practitioner turnover and retention in remote communities of the Northern Territory of Australia, 2013-2015. Human Resources for Health 2017;15:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Northern Territory Government Department of Health. Indicator definition: full time equivalents v1.0. Darwin: NTG Department of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. National hospital cost data collection: Northern Territory 2014/15 Round 19. Sydney: IHPA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao Y, Hanssens P, Byron P, et al. Cost estimates of primary health care activities for remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. Darwin: Northern Territory Department of Health and Community Services, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welfare AIoHa. National Healthcare Agreement: PI 18–Selected potentially preventable hospitalisations, 2016. Canberra: AIHW, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Australian Safety and Compensation Council. The health of nations: the value of a statistical life. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buykx P, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, et al. Systematic review of effective retention incentives for health workers in rural and remote areas: towards evidence-based policy. Aust J Rural Health 2010;18:102–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Freeman T, Baum F, Lawless A, et al. Case study of an aboriginal community-controlled health service in Australia: Universal, rights-based, publicly funded comprehensive primary health care in action. Health Hum Rights 2016;18:93–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Toca L. The world in East Arnhem. 14th National Rural Health Conference. Cairns, Australia: NRHA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gomersall JS, Gibson O, Dwyer J, et al. What Indigenous Australian clients value about primary health care: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41:417–23. 10.1111/1753-6405.12687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.