Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the risk of developing cancers, particularly site-specific cancers, in women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in Taiwan.

Setting

The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan.

Participants

This study was conducted using the nationwide data from 2000 to 2013. In total, 1 466 596 pregnant women with admission for delivery were identified. Subjects with GDM consisted of 47 373 women, while the non-exposed group consisted of 943 199 women without GDM. The participants were followed from the delivery date to the diagnosis of cancer, death, the last medical claim or the end of follow-up (31 December 2013), whichever came first.

Primary outcome measures

Patients with a new diagnosis of cancer (International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition, with clinical modification (ICD-9-CM codes 140–208)) recorded in NHIRD were identified. The risk of 11 major cancer types was assessed, including cancers of head and neck, digestive organs, lung and bronchus, bone and connective tissue, skin, breast, genital organs, urinary system, brain, thyroid gland and haematological system.

Results

The rates of developing cancers were significantly higher in women with GDM compared with the non-GDM group (2.24% vs 1.96%; p<0.001). After adjusting for maternal age at delivery and comorbidities, women with GDM had increased risk of cancers, including cancers of nasopharynx (adjusted HR, 1.739; 95 % CI, 1.400 to 2.161; p<0.0001), kidney (AHR, 2.169; 95 % CI, 1.428 to 3.293; p=0.0003), lung and bronchus (AHR, 1.372; 95 % CI, 1.044 to 1.803; p=0.0231), breast (AHR, 1.234; 95% CI, 1.093 to 1.393; p=0.007) and thyroid gland (AHR, 1.389; 95 % CI, 1.121 to 1.721; p=0.0026).

Conclusion

Women with GDM have a higher risk of developing cancers. Cancer screening is warranted in women with GDM. Future research should be aimed at establishing whether this association is causal.

Keywords: gestational diabetes, cancer, national health insurance research database

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study represents the first one to document that women with GDM have a higher risk of developing cancers of nasopharynx, lung and bronchus and kidney.

This nationwide population-based cohort study included more than one million women, making selection bias minimal.

The use of big data from Taiwan NHIRD also decreased the risk of recall bias, which is inherent to self-reporting, thus making our findings potentially generalisable.

The data from NHIRD lack information on other factors that may be associated with GDM and cancer, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, dietary style, environmental exposure, genetic parameters, subtypes of cancer and family history of cancers.

The relatively short follow-up period (6.84±3.05 years) in our study may not have allowed some slow-growing cancers to be detected.

Introduction

Pregnancy is normally accompanied by insulin resistance, which is facilitated by placental production of diabetogenic hormones. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) develops in pregnant women whose pancreatic islet function is inadequate to overcome the insulin resistance that accompanies pregnancy.1 GDM is associated with adverse outcomes of pregnancy, for example, preeclampsia, macrosomia and caesarean delivery.1 The prevalence of GDM varies worldwide and among racial and ethnic groups,2 and is generally in parallel with the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Indeed, it has been shown that women diagnosed with GDM are at lifetime risk of developing T2DM subsequently.3 Lately, the prevalence of GDM has been on the rise.4 The reasons for this phenomenon may be an increase in maternal age, obesity issues and a decrease in daily physical activity.

Accumulating lines of evidence have demonstrated an association between T2DM and certain types of cancers. Although the exact causes for this phenomenon are not yet fully understood, chronic hyperinsulinemia, which is prompted by insulin resistance, has been proposed to be the major channel through which T2DM can trigger tumour growth. Some studies, although not all, suggested that T2DM may contribute to an increased mortality.5 Interestingly, the increase in cancer risk has been found not only in T2DM but also in pre-diabetes.6 GDM is characterised by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia and increased levels of insulin-like growth factor 1(, which can potentially lead to uncontrolled growth of cells and cancer.1 7 Since GDM has the same characteristics as T2DM and is a predictor for subsequent overt T2DM, it is plausible that GDM may represent a risk factor for the future cancers. Indeed, several studies have been conducted to address whether GDM increases risk of cancer, but yielded mixed results probably because of methodological limitations such as self-reported GDM information, relatively small population and insufficient statistical power resulting from rare occurrence of cancers among young women.7–13

Most previous studies focused on the association between GDM and breast cancer. Only a few have investigated the relationship between GDM and other types of cancers. Moreover, few studies on the association between cancer and GDM have been carried out in Asia-Pacific region where certain types of cancer are particularly prevalent. Therefore, it is unknown whether currently available data can be generalised to different ethnic groups.

The aim of this study was to determine the risk of developing cancers particularly site-specific cancers in women with prior GDM using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which was created by National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) for academic research.14

Materials and methods

Source of data

Data in NHIRD were used. NHIRD contains the registration files and original claim data for reimbursements from the national health insurance (NHI) programme of Taiwan; This NHI programme was implemented in 1995 and covers 99.5% of the 23 million residents in Taiwan. The NHI programme offers a comprehensive, unified and universal health insurance programme to all citizens. The coverage includes outpatient service, inpatient care, dental care, childbirth, physical therapy, preventive healthcare, home care and rehabilitation for chronic mental illnesses.15 The database provides all dates of inpatient and outpatient services, diagnosis, prescriptions, examinations, operations, and expenditures, and is updated biannually.

Patient and public involvement

In the present study, we used NHIRD, which is the data of insurance claims with anonymised identifications. No patients or public were involved.

Study groups

This study used data published by the NHRI in Taiwan and covered the years from 2000 to 2013. The diagnostic coding of the NHI in Taiwan was performed according to the International Classification of Disease, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

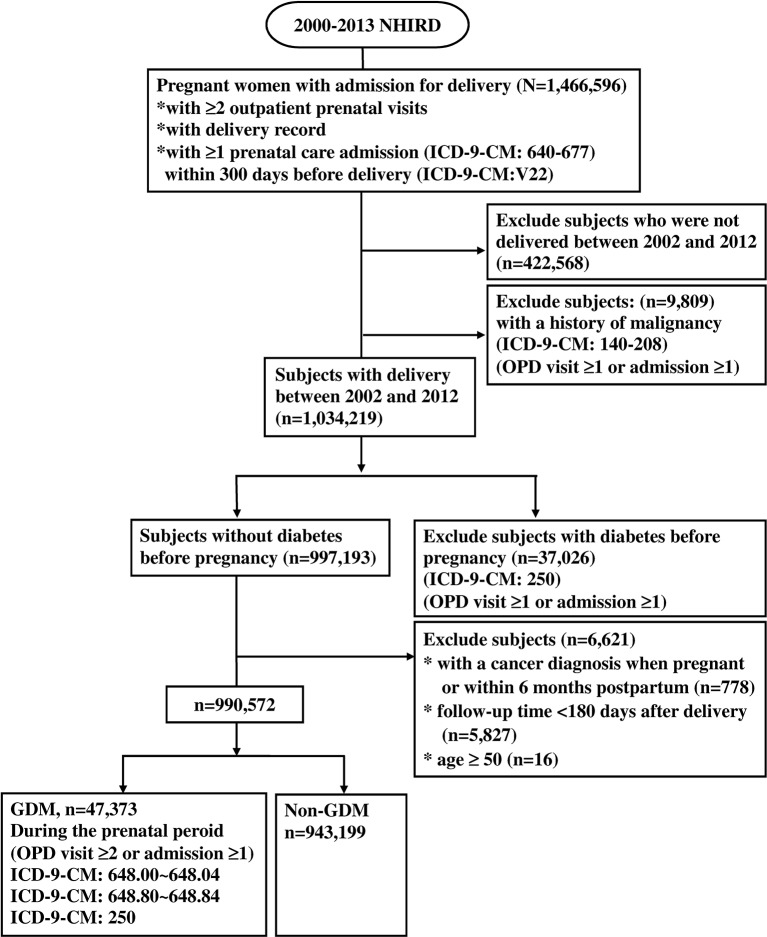

A total of 1 466 596 pregnant women with admission for delivery were found in the NHIRD between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2013 (figure 1). Subjects were traced back 2 years before delivery to identify if there was a past history of malignancy or diabetes and assess baseline comorbidities, which may confound the association between GDM and malignancy. In this context, women with admission for delivery between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2012 were further analysed to avoid pre-existing malignancy and ensure adequate period of time in follow-up. Among these women, we identified 47 373 women who had been diagnosed with gestational diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 648 250), and had at least two consensus diagnoses at prenatal outpatient visits or at least one diagnosis at inpatient admissions during the prenatal period to ensure the validity of diagnosis (figure 1). The remaining 943 199 women without GDM, diabetes or malignancy were used as the non-exposed group. The incidence of GDM was 4.78 in 100 deliveries during the 11 year span (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for population selection. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition, with clinical modification; NHIRD, National Health Insurance Research Database; OPD, outpatient department.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Pregnancy women with GDM | Pregnancy women without GDM | P value | |

| Number of population, n (%) | 47 373 (4.78) | 943 199 (95.22) | |

| Age, y, mean±SD | 31.61±4.54 | 28.83±4.89 | <0.0001 |

| Age group, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| ≤20 | 407 (0.86) | 45 942 (4.87) | |

| 21–30 | 18 617 (39.30) | 558 108 (59.17) | |

| 31–40 | 27 203 (57.42) | 329 929 (34.98) | |

| 41–50 | 1146 (2.42) | 9220 (0.98) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension (ICD-9:401–405) | 1479 (3.12) | 7743 (0.82) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia (ICD-9:272) | 1132 (2.39) | 8197 (0.87) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease (ICD-9:070, 571) | 3165 (6.68) | 44 509 (4.72) | <0.0001 |

| Infertility, female (ICD-9:628) | 8001 (16.89) | 94 405 (10.01) | <0.0001 |

| Kidney disease (ICD-9:582–3, 585–6, 588) | 51 (0.11) | 626 (0.07) | 0.0008 |

GDM, gestational diabetes; ICD-9, International Classification of Disease, ninth Revision.

Those women who were not admitted for delivery within the time frame between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2012 were excluded (n=422 568). Subjects with a history of malignancy (ICD-9-CM codes 140 to 208) (n=9809) 2 years before delivery, or diabetes (ICD-9-CM codes 250) (n=37 026) before pregnancy were excluded. The date of delivery was set as the index date. To avoid the inclusion of patients with cancers that arose during or before pregnancy, GDM and the non-exposed participants were followed for 180 days after delivery until malignancy diagnosis, death, the last medical claim or the end of study follow-up (31 December 2013), whichever came first. We excluded the women with a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy or within 180 days post-partum (n=778). Five thousand eight hundred twenty-seven patients were also excluded due to loss of follow-up within 180 days after delivery.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was defined as a new diagnosis of any cancer (ICD-9-CM codes 140–208) recorded in NHIRD between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2013.

Sub-classification of cancers

We classified cancers into the 11 groups as previously described,12 on basis of the ICD-9-CM: cancers of head and neck, digestive organs, lung and bronchus, bone and connective tissue, skin, breast, genital organs, urinary system, brain, thyroid gland and haematological system.

Baseline comorbidities were assessed for 2 years and included hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), liver disease (ICD-9-CM codes 070, 571), infertility (ICD-9-CM codes 628) and kidney disease (ICD-9-CM codes 582–3, 585–6, 588). These comorbidities were selected because they have been shown to be associated with both GDM and risk of cancers.16–25

Statistical analysis

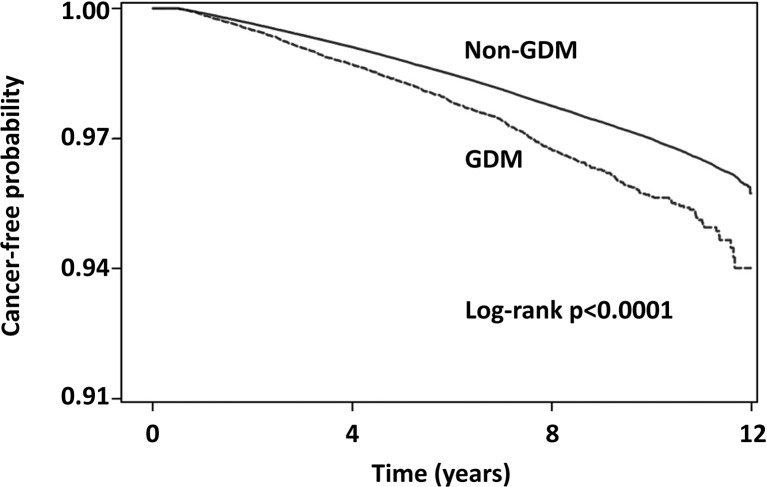

Continuous variables were presented as the mean with SDs. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables, and the differences among continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test. The proportion of patients with cancer was plotted by Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank test constructed to compare the cumulative incidence of any type of cancer between subjects with and without GDM. The HR of cancer was estimated by Cox proportional regression analysis, which was adjusted for potential confounding variables, such as age and comorbidities. The predictors satisfied the proportional hazard assumption in Cox model. The statistical significance was inferred at a two-sided p value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) System, V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted using Stata V.12 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Table 1 lists the clinical characteristics of subjects. Overall, 990 572 women were analysed. Among them, 47 373 women had GDM. The remaining 943 199 women without GDM served as the non-exposed group. The average length of follow-up was 6.84±3.05 years, and mean age was 28.97±4.91 years. The incidence of GDM was 4.78% during the 11 year span. Women with GDM had a higher rate of comorbidities than those in the non-exposed group, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, liver disease, infertility and kidney disease (table 1).

Table 2 shows that the adjusted HR of developing any type of cancer among women with GDM was 1.197 (95% CI, 1.125 to 1.274) compared with women without GDM after adjusting for age and comorbidities.

Table 2.

HR of developing cancer in relation to baseline characteristics of study participants

| Crude HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Patients | ||||

| GDM | 1.421 (1.336 to 1.512) | <0.0001 | 1.197 (1.125 to 1.274) | 0.0012 |

| Non-GDM | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| Age | ||||

| ≤20 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 21–30 | 1.627 (1.488 to 1.779) | <0.0001 | 1.581 (1.446 to 1.729) | <0.0001 |

| 31–40 | 2.843 (2.600 to 3.109) | <0.0001 | 2.678 (2.448 to 2.930) | <0.0001 |

| 41–50 | 4.883 (4.291 to 5.556) | <0.0001 | 4.479 (3.933 to 5.100) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension (ICD-9: 401–405) | 1.471 (1.291 to 1.677) | <0.0001 | 1.114 (0.976 to 1.272) | 0.1101 |

| Dyslipidemia (ICD-9: 272) | 1.866 (1.648 to 2.113) | <0.0001 | 1.395 (1.229 to 1.583) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease (ICD-9: 070, 571) | 1.573 (1.486 to 1.665) | <0.0001 | 1.432 (1.351 to 1.517) | <0.0001 |

| Infertility, female (ICD-9: 628) | 1.397 (1.340 to 1.457) | <0.0001 | 1.185 (1.136 to 1.236) | <0.0001 |

| Kidney disease (ICD-9: 582–3, 585–6, 588) | 2.077 (1.403 to 3.073) | 0.0003 | 1.623 (1.095 to 2.404) | 0.0159 |

GDM, gestational diabetes; ICD-9, International Classification of Disease, ninth Revision.

Patients with GDM were diagnosed with cancer (n=1063, 2.24%) at a significantly higher rate than those without GDM (n=18 444, 1.96%; p<0.001) (table 3). Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence rates of any type of cancer in patients with or without GDM from the index date until the first occurrence of cancer. The patients with GDM had higher cancer incidence rates compared with those patients without GDM (log-rank test: p<0.0001).

Table 3.

HR of the first cancer diagnosis between GDM group and non-GDM group

| (ICD-9 code) | Women with GDM (n=47 373) | Women without GDM (n=9 43 199) |

Crude HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value |

| Head and neck | ||||||

| Oral and pharynx (140–1, 143–6, 148–9) | 19 (0.04) | 389 (0.04) | 1.230 (0.776 to 1.950) | 0.3792 | 1.105 (0.695 to 1.759) | 0.6724 |

| Nasopharynx (147) | 90 (0.19) | 1151 (0.12) | 1.897 (1.530 to 2.351) | <0.0001 | 1.739 (1.400 to 2.161) | <0.0001 |

| Digestive system | ||||||

| Stomach (151) | 18 (0.04) | 256 (0.03) | 1.703 (1.056 to 2.749) | 0.0291 | 1.322 (0.816 to 2.142) | 0.2570 |

| Colorectum (153–4) | 100 (0.21) | 1705 (0.18) | 1.420 (1.160 to 1.738) | 0.0007 | 1.180 (0.963 to 1.447) | 0.1099 |

| Liver (155) | 87 (0.18) | 1393 (0.15) | 1.504 (1.211 to 1.868) | 0.0002 | 1.242 (0.998 to 1.545) | 0.0521 |

| Pancreas (157) | 17 (0.04) | 314 (0.03) | 1.316 (0.808 to 2.145) | 0.2699 | 1.072 (0.655 to 1.755) | 0.7807 |

| Genital system | ||||||

| Cervix uteri (180) | 37 (0.08) | 962 (0.10) | 0.925 (0.666 to 1.285) | 0.6429 | 0.903 (0.649 to 1.256) | 0.5438 |

| Uterus (179, 182) | 42 (0.09) | 803 (0.09) | 1.323 (0.970 to 1.805) | 0.0768 | 1.051 (0.769 to 1.437) | 0.7534 |

| Ovary (183) | 50 (0.11) | 1146 (0.12) | 1.061 (0.800 to 1.409) | 0.6797 | 0.963 (0.724 to 1.280) | 0.7928 |

| Urinary system | ||||||

| Urinary bladder (188) | 9 (0.02) | 162 (0.02) | 1.387 (0.709 to 2.715) | 0.3395 | 1.034 (0.525 to 2.033) | 0.9236 |

| Kidney (189) | 25 (0.05) | 245 (0.03) | 2.573 (1.704 to 3.885) | <0.0001 | 2.169 (1.428 to 3.293) | 0.0003 |

| Haematological system | ||||||

| Leukaemia (204–8) | 11 (0.02) | 359 (0.04) | 0.742 (0.407 to 1.352) | 0.3293 | 0.735 (0.402 to 1.344) | 0.3169 |

| Lymphoma (200–3) | 19 (0.04) | 596 (0.06) | 0.771 (0.488 to 1.217) | 0.2641 | 0.774 (0.489 to 1.226) | 0.2754 |

| Bone and connective tissue (170–1) | 7 (0.01) | 271 (0.03) | 0.618 (0.292 to 1.309) | 0.0708 | 0.582 (0.274 to 1.236) | 0.1590 |

| Lung and bronchus (162) | 56 (0.12) | 846 (0.09) | 1.666 (1.271 to 2.184) | 0.0002 | 1.372 (1.044 to 1.803) | 0.0231 |

| Skin (173) | 15 (0.03) | 201 (0.02) | 1.834 (1.085 to 3.101) | 0.0236 | 1.664 (0.980 to 2.825) | 0.0594 |

| Breast (174) | 284 (0.60) | 4373 (0.46) | 1.654 (1.467 to 1.866) | <0.0001 | 1.234 (1.093 to 1.393) | 0.0007 |

| Brain (191) | 19 (0.04) | 331 (0.04) | 1.382 (0.870 to 2.195) | 0.1703 | 1.232 (0.772 to 1.968) | 0.3818 |

| Thyroid (193) | 91 (0.19) | 1423 (0.15) | 1.582 (1.279 to 1.956) | <0.0001 | 1.389 (1.121 to 1.721) | 0.0026 |

| Other sites | 91 (0.16) | 1719 (0.18) | 1.251 (0.989 to 1.583) | 0.0619 | 1.154 (0.910 to 1.462) | 0.2373 |

| Total (140–208) | 1063 (2.24) | 18 444 (1.96) | 1.421 (1.336 to 1.512) | <0.0001 | 1.197 (1.125 to 1.274) | <0.0001 |

Model was adjusted for age, hypertension, dyslipidemia, liver disease, infertility and kidney disease.

GDM, gestational diabetes; ICD-9, International Classification of Disease, ninth revision.

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence rates of any type of cancer in patients with or without gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) from the index date until the first occurrence of the cancer using Kaplan-Meier methods.

Adjusting for maternal age at delivery and comorbidities, women with a history of GDM had an increased risk of cancers, including cancers of nasopharynx (AHR, 1.739; 95 % CI, 1.400 to 2.161; p<0.0001), kidney (AHR, 2.169; 95 % CI, 1.428 to 3.293, p=0.0003), lung and bronchus (AHR, 1.372; 95 % CI, 1.044 to 1.803; p=0.0231), breast (AHR, 1.234; 95 % CI, 1.093 to 1.393; p=0.0007) and thyroid gland (AHR, 1.389; 95 % CI, 1.121 to 1.721; p=0.0026) (table 3).

Discussion

The major findings of this study are as follows: (1) GDM is associated with a 19.7% higher risk of developing malignancy. (2) Women with GDM are at a higher risk of developing cancers of nasopharynx, lung and bronchus, kidney, breast and thyroid glands.

One of our novel findings is that women with GDM are more likely to develop nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) during the period of follow-up. NPC differs from other head and neck cancers in epidemiology, histology, natural history and response to treatment. NPC is one of the neoplasms that are linked to infectious agents and displays a distinct racial and geographic distribution. While NPC is rare in Europe and America, it is endemic in South-eastern Asia including Taiwan where Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is prevalent.26 The recrudescence of EBV in immunocompromised patients has been characterised by activating the expression of EBV latency genes, consequently immortalising the infected cells and leading to carcinogenesis.27 Indeed, the immune dysfunction inherent to T2DM increases the susceptibility to various infections and risk of reactivating latent virus infections as well, eventually contributing to higher rates of mortality.28–31 It is unknown whether GDM, a pre-diabetes condition, is pathogenetically linked to reactivation of EBV infection and subsequent malignant transformation. It is also unknown whether shared environmental risk factors and genetic susceptibility can be other explanations.

Another novel finding in our study is that the risk of developing kidney cancer is significantly higher in women with GDM, compared with those without GDM. The aetiology of kidney cancer remains elusive, but smoking, hypertension, obesity, analgesics use, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and genetic defects are potential risk factors.32 33 Of these factors, obesity and hypertension also characterise GDM.1 Indeed, it has been shown that patients with T2DM have a higher risk of developing kidney cancers.34 35 In fact, GDM is associated with subsequent development of T2DM and CKD.3 25 It is unknown whether prevention of CKD would reduce the risk of kidney cancer in women with GDM.

Our study is also the first to demonstrate the association between GDM and lung cancers, which is the most common cancer around the world.36 The prevalence of both lung cancer and GDM has been on the increase in Taiwan and worldwide.4 37 Whether this association is causal remains to be determined. Importantly, GDM and lung cancer do share common risk factors such as smoking, dietary style and obesity.36 38 It is unknown whether modification of these risk factors could impact this association.

In the present study, we also observed a clear association between GDM and breast cancer. Previous studies on the association between GDM and breast cancer have produced mixed results.7–13 39–44 The reasons for the discrepancy are not clear. They could be explained by methodological limitations. First, most of these studies were based on self-reported information about GDM,9–11 39 41 42 44 which is prone to recall bias. Second, small sample size and relatively rare occurrence of cancer among young women may result in inadequate statistical power, contributing to inconsistency. In these regards, our big database from Taiwan NHIRD confers an advantage to overcome these methodological limitations.

In agreement with a previous study,8 we showed that GDM was associated with a 38.9% higher risk of developing thyroid cancer. Interestingly, a large study from USA found that the risk of thyroid cancer was significantly increased in women, but not in men, with diabetes.45 Taken together, women with GDM may represent a readily recognisable subgroup that deserves a more intensive surveillance for thyroid cancer.

The elucidation of the relationship between GDM and later cancer risk may not be straightforward. It is conceivable that GDM may impact subsequent cancer risk through certain direct or indirect pathophysiological mechanisms such as hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia secondary to insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Shared risk factors for GDM and cancers can be other explanations, for example smoking, alcohol drinking, obesity, physical inactivity, hypertension and dietary style.

Insulin has mitogenic effects on cells.46 On the other hand, hyperglycemia can induce production of reactive oxygen species, which can initiate carcinogenesis by damaging cellular DNA.47 48

Recently, the role of systemic inflammation in the pathogenesis of GDM has gained more and more attention. Increased circulating levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein have been observed in GDM independent of obesity,49 50 suggesting GDM as a state of low-grade inflammation. Inflammation is also a hallmark of cancer and is widely recognised to influence all cancer stages from cell transformation to metastasis.51 Therefore, chronic and systemic inflammation may represent the biological phenomenon linking GDM to cancer development. Future investigations on the role of low-grade inflammation in GDM may help identify biomarkers that can better predict, diagnose and monitor the evolution of GDM. Moreover, specific inflammatory pathways may represent novel targets for treatment and prevention of long-term adverse outcomes of GDM, including cancer development.

There were several strengths in this study. First, this is population-based study with a large nationally representative sample from Taiwan NHIRD, thus making selection bias minimised. Second, the use of NHIRD reduced the potential recall bias that is inherent to self-reporting.

Limitations of this study included the lack of information about parity, multiple GDM pregnancy and the histology, subtype and staging of cancer. Second, our study did not have information about potential confounders such as dietary, obesity, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, environmental exposure and genetic parameters. Third, the follow-up period may not be long enough to allow detection of cancers in young women.

Conclusions

This population-based analysis of Taiwan NHIRD showed that women with GDM in Taiwan have an increased risk of developing malignancy including cancers of nasopharynx, lung, kidney, breast and thyroid gland. Prevention of GDM may be an important strategy in curbing the development of certain types of cancers in the future. Our study also highlights under-recognised cancers in women with GDM that warrants further investigations to develop different surveillance strategies for cancer development in GDM patients in different ethnic groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Grant CIRPD1D0031). The authors thank Research Services Center For Health Information and Chang Gung University for statistical consultation. This study was based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the National Health Insurance Administration, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-SP proposed and designed the study. Y-SP also drafted the manuscript. M-HT supervised the study and critically edited the manuscript and finally approved the version to be submitted. J-RL designed the study’s analytic strategy and conducted the data analysis. B-HC and CH contributed the study design and prepared the Methods and the Discussion sections of the text, Y-HL and C-HS helped conduct the literature review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital, grant number CIRPD1D0031.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation (IRB 103-2572B).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:676 10.2337/dc10-0719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dornhorst A, Paterson CM, Nicholls JS, et al. High prevalence of gestational diabetes in women from ethnic minority groups. Diabet Med 1992;9:820–5. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1992.tb01900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chodick G, Elchalal U, Sella T, et al. The risk of overt diabetes mellitus among women with gestational diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med 2010;27:779–85. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care 2007;30(Suppl 2):S141–6. 10.2337/dc07-s206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:2754–64. 10.1001/jama.2008.824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stattin P, Björ O, Ferrari P, et al. Prospective study of hyperglycemia and cancer risk. Diabetes Care 2007;30:561–7. 10.2337/dc06-0922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tong GX, Cheng J, Chai J, et al. Association between gestational diabetes mellitus and subsequent risk of cancer: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:4265–9. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.10.4265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bejaimal SA, Wu CF, Lowe J, et al. Short-term risk of cancer among women with previous gestational diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med 2016;33:39–46. 10.1111/dme.12796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Powe CE, Tobias DK, Michels KB, et al. History of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Incident Invasive Breast Cancer among Parous Women in the Nurses’ Health Study II Prospective Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:321–7. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park YM, O’Brien KM, Zhao S, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus may be associated with increased risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2017;116:960–3. 10.1038/bjc.2017.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dawson SI. Long-term risk of malignant neoplasm associated with gestational glucose intolerance. Cancer 2004;100:149–55. 10.1002/cncr.20013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sella T, Chodick G, Barchana M, et al. Gestational diabetes and risk of incident primary cancer: a large historical cohort study in Israel. Cancer Causes Control 2011;22:1513–20. 10.1007/s10552-011-9825-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xie C, Wang W, Li X, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of the literature. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;7:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Y-C, Yeh H-Y, Wu J-C, et al. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: administrative health care database as study object in bibliometrics. Scientometrics 2011;86:365–80. 10.1007/s11192-010-0289-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsing AW, Ioannidis JP. Nationwide population science: lessons from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1527–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuzu OF, Noory MA, Robertson GP. The Role of Cholesterol in Cancer. Cancer Res 2016;76:2063–70. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stocks T, Van Hemelrijck M, Manjer J, et al. Blood pressure and risk of cancer incidence and mortality in the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Project. Hypertension 2012;59:802–10. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang HP, Cook LS, Weiderpass E, et al. Infertility and incident endometrial cancer risk: a pooled analysis from the epidemiology of endometrial cancer consortium (E2C2). Br J Cancer 2015;112:925–33. 10.1038/bjc.2015.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, et al. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1683 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lowrance WT, Ordoñez J, Udaltsova N, et al. CKD and the risk of incident cancer. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25:2327–34. 10.1681/ASN.2013060604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baumfeld Y, Novack L, Wiznitzer A, et al. Pre-Conception Dyslipidemia Is Associated with Development of Preeclampsia and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139164 10.1371/journal.pone.0139164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tobias DK, Chavarro JE, Williams MA, et al. History of infertility and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective analysis of 40,773 pregnancies. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1219–25. 10.1093/aje/kwt110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sridhar SB, Xu F, Darbinian J, et al. Pregravid liver enzyme levels and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus during a subsequent pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1878–84. 10.2337/dc13-2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mirghani Dirar A, Doupis J. Gestational diabetes from A to Z. World J Diabetes 2017;8:489–511. 10.4239/wjd.v8.i12.489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dehmer EW, Phadnis MA, Gunderson EP, et al. Association Between Gestational Diabetes and Incident Maternal CKD: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:112–22. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu MC, Yuan JM. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol 2002;12:421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med 2000;343:481–92. 10.1056/NEJM200008173430707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Plouffe JF, Silva J, Fekety R, et al. Cell-mediated immunity in diabetes mellitus. Infect Immun 1978;21:425–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geerlings SE, Hoepelman AIM. Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Immunol Med Microbiol 1999;26:259–65. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berrou J, Fougeray S, Venot M, et al. Natural killer cell function, an important target for infection and tumor protection, is impaired in type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2013;8:e62418 10.1371/journal.pone.0062418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar M, Roe K, Nerurkar PV, et al. Impaired virus clearance, compromised immune response and increased mortality in type 2 diabetic mice infected with West Nile virus. PLoS One 2012;7:e44682 10.1371/journal.pone.0044682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2011;60:615–21. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chow WH, Dong LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2010;7:245–57. 10.1038/nrurol.2010.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Larsson SC, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and incidence of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetologia 2011;54:1013–8. 10.1007/s00125-011-2051-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tseng CH. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Kidney Cancer Risk: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis of the National Health Insurance. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142480 10.1371/journal.pone.0142480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dela Cruz CS, Tanoue LT, Matthay RA. Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med 2011;32:605–44. 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tseng CH. Diabetes but not insulin increases the risk of lung cancer: a Taiwanese population-based study. PLoS One 2014;9:e101553 10.1371/journal.pone.0101553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1997;278:1078–83. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550130052036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Troisi R, Weiss HA, Hoover RN, et al. Pregnancy characteristics and maternal risk of breast cancer. Epidemiology 1998;9:641–7. 10.1097/00001648-199811000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cnattingius S, Torrång A, Ekbom A, et al. Pregnancy characteristics and maternal risk of breast cancer. JAMA 2005;294:2474–80. 10.1001/jama.294.19.2474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brasky TM, Li Y, Jaworowicz DJ, et al. Pregnancy-related characteristics and breast cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:1675–85. 10.1007/s10552-013-0242-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Hyperinsulinaemia and increased risk of breast cancer: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Cancer Causes Control 2004;15:267–75. 10.1023/B:CACO.0000024225.14618.a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perrin MC, Terry MB, Kleinhaus K, et al. Gestational diabetes and the risk of breast cancer among women in the Jerusalem Perinatal Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;108:129–35. 10.1007/s10549-007-9585-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rollison DE, Giuliano AR, Sellers TA, et al. Population-based case-control study of diabetes and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women living in US southwestern states. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:447–56. 10.1093/aje/kwm322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Sabra MM, Brenner A, et al. Diabetes and thyroid cancer risk in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Thyroid 2011;21:957–63. 10.1089/thy.2010.0396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, et al. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009;16:1103–23. 10.1677/ERC-09-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chandrasekaran K, Swaminathan K, Chatterjee S, et al. Apoptosis in HepG2 cells exposed to high glucose. Toxicol In Vitro 2010;24:387–96. 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang Y, Zhou J, Wang T, et al. High level glucose increases mutagenesis in human lymphoblastoid cells. Int J Biol Sci 2007;3:375–9. 10.7150/ijbs.3.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Atègbo JM, Grissa O, Yessoufou A, et al. Modulation of adipokines and cytokines in gestational diabetes and macrosomia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4137–43. 10.1210/jc.2006-0980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wolf M, Sandler L, Hsu K, et al. First-trimester C-reactive protein and subsequent gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:819–24. 10.2337/diacare.26.3.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leonardi GC, Accardi G, Monastero R, et al. Ageing: from inflammation to cancer. Immun Ageing 2018;15:1 10.1186/s12979-017-0112-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.