Abstract

Objective

We aimed to evaluate the effects on depression scores of a lifestyle-focused cardiac support programme delivered via mobile phone text messaging among patients with coronary heart disease (CHD).

Design

Substudy and secondary analysis of a parallel-group, single-blind randomised controlled trial of patients with CHD.

Setting

A tertiary hospital in Sydney, Australia.

Intervention

The Tobacco, Exercise and dieT MEssages programme comprised four text messages per week for 6 months that provided education, motivation and support on diet, physical activity, general cardiac education and smoking, if relevant. The programme did not have any specific mental health component.

Outcomes

Depression scores at 6 months measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Treatment effect across subgroups was measured using log-binomial regression model for the binary outcome (depressed/not depressed, where depressed is any score of PHQ-9 ≥5) with treatment, subgroup and treatment by subgroup interaction as fixed effects.

Results

Depression scores at 6 months were lower in the intervention group compared with the control group, mean difference 1.9 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.4, p<0.0001). The frequency of mild or greater depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 scores≥5) at 6 months was 21/333 (6.3%) in the intervention group and 86/350 (24.6%) in the control group (relative risk (RR) 0.26, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.40, p<0.001). This proportional reduction in depressive symptoms was similar across groups defined by age, sex, education, body mass index, physical activity, current smoking, current drinking and history of depression, diabetes and hypertension. In particular, the rates of PHQ-9 ≥5 among people with a history of depression were 4/44 (9.1%) vs 29/62 (46.8%) in intervention vs control (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.51, p<0.001), and were 17/289 (5.9%) vs 57/288 (19.8%) among others (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.50, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Among people with CHD, a cardiac support programme delivered via mobile phone text messaging was associated with fewer symptoms of mild-to-moderate depression at 6 months in the treatment group compared with controls.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12611000161921.

Keywords: text message, mobile phones, cardiovascular diseases, mental health, diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this trial is the parallel-group, prospective, randomised controlled design.

The trial had a relatively large sample size.

With respect to limitations, it is a single-centre study.

Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 tool, which is designed as a screening tool.

Introduction

Depression is common among patients with chronic diseases including coronary heart disease (CHD) and often under-recognised and untreated.1 Comorbid depression affects daily function and is associated with substantial impairment in health-related quality of life and worse clinical outcomes in patients with CHD.2–4 As well as the direct negative impact of depression on the well-being of patients and their carers, depression after myocardial infarction is associated with substantially increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.5 Patients with depression and CHD need effective treatment and support for both conditions. Attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following a cardiac event decreases morbidity, mortality, depressive symptoms and improves quality of life.6 7 Nevertheless, access to cardiac rehabilitation remains difficult, especially for those who are financially disadvantaged, part of an ethnic minority group, older or living far from health centres with limited access to transport.8 Also, research suggests some simple interventions delivered in the community/primary care can improve mental health outcomes and integrating treatments into chronic disease management improves outcomes.9 10 Innovation is clearly needed to provide ongoing support for patients with cardiac and other chronic conditions, within limited healthcare resources.

In recent years, mobile phone technologies such as text messaging interventions comprising health education and reminders have shown promise in improving healthcare service delivery,11 increasing medication adherence12 and improving primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, for example, improving glycaemic control among people with diabetes,13 and improving smoking quit rates.14 With respect to mental health, previous trials have reported that automated text messaging offered a feasible and acceptable means of monitoring depression and has the potential to improve outcomes in patients with comorbid depression.15 16 A systematic review of 6 trials involving 577 participants with mental health disorders (depression, alcohol dependence, schizophrenia and mood disorders) showed text messaging for health education, therapy goals and medication reminders interventions significantly improved several mental health-related outcomes in five studies including depression and quality of life scores.17 However, most of these were pilot studies and little is known about the extent to which text messaging might reduce depressive symptoms in people with CHD. We conducted the Tobacco, Exercise and dieT MEssages (TEXT ME) randomised controlled trial in patients with CHD that addressed multiple cardiovascular risk factors.18 The TEXT ME trial resulted in a modest improvement in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and greater improvement in other cardiovascular disease risk factors including blood pressure, body mass index, physical activity and smoking among patients with CHD.19 The objective of this secondary and exploratory analysis of the TEXT ME study was to examine if the text message support programme had an impact on depressive symptoms at 6 months.

Methods

Study design

The current analyses were a prespecified secondary analysis of the TEXT ME trial.18 In brief, TEXT ME was a parallel-design, single-blind, randomised controlled clinical trial enrolling 710 patients with CHD from a tertiary hospital in Sydney, Australia between September 2011 and November 2013.19 The text messaging programme and its development process are detailed elsewhere.19

Participants

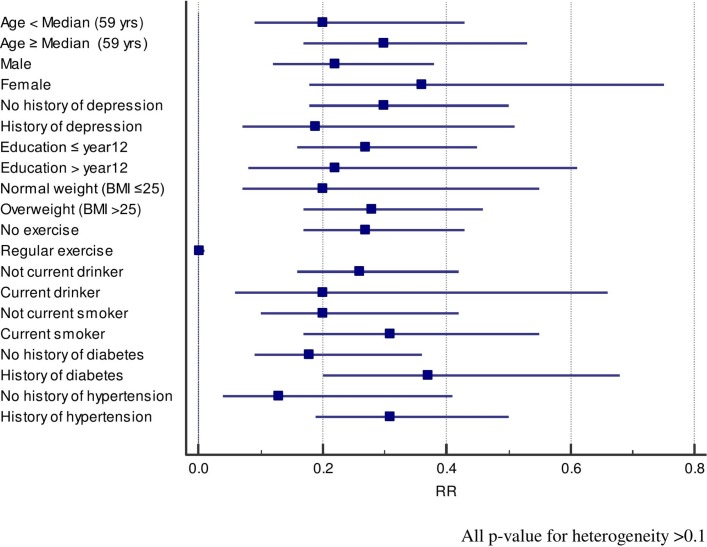

Potential participants were identified through screening daily admissions, coronary angiogram case lists and cardiology outpatient clinic lists from a large tertiary care hospital which serves a diverse population in terms of ethnicity and socioeconomic status in the Western Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia. We included patients older than 18 years, with documented CHD who were able to provide informed consent. CHD was defined as documented myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention, or proven angiographically and documented before consent. Patients were excluded if they did not have an active mobile phone, sufficient English language proficiency to read text messages or were referred for evaluation of congenital heart disease or coronary anomalies. Figure 1 displays the study flow chart. A total of 1301 patients with CHD were invited to participate, 591 did not meet all inclusion criteria or declined to participate and 710 were randomised in TEXT ME.19 Twenty-seven participants (including 12 who were unable to be contacted, 5 who died and 10 with missing data for depression symptoms at 6 months) were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the current analyses were performed on 683 participants (96%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart. PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in the design of the study, recruitment and conduct of the study. However, during the process evaluation we shared the results of the study with the participants and collected feedback from the participants. The process evaluation focus group discussions took place after participants completed the intervention and follow-up visit.

Randomisation, trial procedure and intervention

Randomisation was performed using a computerised randomisation programme through a secure web interface. The random allocation sequence was in a uniform 1:1 allocation ratio with a block size of 8 and was concealed from study personnel. After recruitment and discharge from hospital, if they were hospitalised, patients would receive a text message informing them of their allocation. Data were collected during face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire at baseline and 6 months by trained research assistants at the outpatient cardiology clinic of Westmead Hospital. At study entry, all intervention participants were provided brief training on how to read, delete and save the text messages. Data entry was performed by study staff through entering data into the secure web interface. The web-based computer program was set to send messages to patients randomised to the intervention. The message programme development was based on behaviour change techniques linked to the theoretical framework reported by Abraham and Michie.20 21 In brief, it involved regular semi-personalised text messages providing advice, motivation and information that aimed to improve general heart health, diet, physical activity and encourage smoking cessation (where relevant).22 Participants randomised to the intervention group received four text messages per week for 24 weeks. Participants received minimum information on depressive symptoms being common in patients with CHD, and were advised to seek further help when needed, which is aligned with the curriculum of secondary prevention. For example, participants were encouraged to seek additional support “Not having support of family and friends can worsen heart disease—if you need help, do not be afraid to ask”. The design, development and samples of the text messages for TEXT ME have been described in a separate paper.22 Examples of text messages used in the TEXT ME are provided in online supplementary table S1.

bmjopen-2018-022637supp001.pdf (477.1KB, pdf)

Variables and outcomes

Data were collected on demographics, medical history and disease factors, including age, sex, years of education, current smoking and drinking status, history of diabetes, history of hypertension and history of depression. The history of depression included questions on prior treatment with medicines, counselling or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Physical activity was assessed with the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire.23 Anthropometric measurements of weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure were measured according to standardised procedures at baseline and at 6 months. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the 12 item Short Form (SF-12) questionnaire at baseline and 6 months.24

Depressive symptoms were assessed at 6 months using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The questionnaire was only administered at the follow-up visit as there were concerns that assessment at baseline while in hospital was not a true reflection of baseline, and that repeating this questionnaire at two time points may impact responses. The PHQ-9 is a depression screening tool which generates a total score from 0 to 27. Scores are categorised as 0–4 no depression, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15–19 moderately severe depression and 20–27 severe depression.25 The PHQ-9 has been shown to have reasonable sensitivity (81.5) and specificity (80.6) at cut-off score ≥5 for patients with CHD25 and has been widely used to detect depression symptoms in clinical settings.26–28 The PHQ-9 has shown good reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.89 and 0.86) and validity with similar tools used to screen for depression (ie, PHQ-9 was found to be highly correlated with scores on the Beck Depression Inventory in the general population, r=0.73).

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted on data using IBM SPSS V.20.0 (IBM, USA) and SAS V.9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The primary end point was the difference in PHQ-9 scores between intervention and control groups at 6 months. Baseline variables were summarised as frequency data, means and SD. The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was used to evaluate distribution of the PHQ-9 scores. The mean difference in intervention and control group depression scores at 6 months were compared using an independent t-test, and between depression severity categories by Fisher’s exact test. The relative risks (RR) were reported with 95% CIs for group differences and in people with a history of depression. We conducted a post hoc analysis with PHQ-9 scores dichotomised at ≥5 representing mild symptoms of depression or greater. For the subgroup analysis, we performed a log binomial model for the binary outcome (depressed/not depressed, where depressed is any score of PHQ-9 ≥5) with treatment, subgroup and treatment by subgroup interaction as fixed effects. No baseline or any other covariates were included. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the 683 participants included in the analyses and the 27 who were excluded (figure 1).

The mean age of participants was 58±9 years, 18% were women. Sixteen per cent had a history of depression of whom 60% reported prior treatment with counselling, 25% medication and 3% ECT. Almost two-thirds of the participants (62%) had history of hypertension and one-third (32%) had a history of diabetes. Baseline characteristics were similar between the randomised groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristics | Intervention group (n=333) n (%) |

Control group (n=350) n (%) |

| Age, mean (SD) years | 57.9 (9.0) | 57.3 (9.2) |

| Women | 61 (18.3) | 61 (17.4) |

| Education, mean (SD), years | 11.4 (3.5) | 11.5 (3.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 mean (SD) | 29.7 (6.0) | 29.6 (5.9) |

| Physical activity—regular exercise | 32 (9.6) | 35 (10.0) |

| Current drinker | 86 (25.8) | 116 (33.1) |

| Current smoker | 174 (52.3) | 189 (54.0) |

| History of diabetes | 105 (31.5) | 114 (32.6) |

| History of hypertension | 212 (63.7) | 212 (60.6) |

| History of depression | 44 (13.2) | 62 (17.7) |

| Prior medication | 14/44 (31.8) | 13/62 (21.0) |

| Prior psychological counselling | 25/44 (56.8) | 41/62 (66.1) |

| Prior electroconvulsive therapy | 3/44 (6.8) | 0/62 (0.0) |

Effects of text messaging on depression

Depression scores at 6 months were significantly lower (better) in the intervention group compared with the control group, with a mean difference of 1.9 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.4, p<0.0001) on the PHQ-9. There were significantly fewer participants categorised as having mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression in the intervention group compared with the control group (p<0.001). The frequency of mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 scores 5–14) at 6 months was 6% in the intervention and 25% in the control group (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.40, p<0.001, unadjusted). The number of participants reporting any depression (PHQ-9 ≥5) was significantly higher in the control group compared with the intervention group (86 vs 21) (table 2).

Table 2.

Depression scores (PHQ-9) at 6 months

| Variables | Intervention (n=333) n (%) |

Control (n=350) n (%) |

Mean difference (95% CI) | P values |

| PHQ-9 total score, mean (SD) | 1.0 (2.2) | 2.9 (3.3) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.4) | <0.0001* |

| No depression (score 0–4) | 312 (93.7) | 264 (75.4) | ||

| Mild depression (score 5–9) | 16 (4.8) | 68 (19.4) | ||

| Moderate depression (score 10–14) | 4 (1.2) | 16 (4.6) | ||

| Moderately severe (score 15–19) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Severe depression (score 20–27) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Any depression (score 5–27) | 21 (6.3) | 86 (24.6) | <0.001† |

*Independent t-test.

†Fisher’s exact test.

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Table 3 reports the difference in the distribution of the PHQ-9 items at 6 months between the intervention and control groups. The magnitude of the differences between groups was fairly consistent for PHQ-9 items 1–7 at 6 months. The frequency of participants endorsing PHQ-9 item 9 relating to suicidality was 0.6% in the intervention group vs 0.9% in the control group (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.12 to 4.17, p=0.696) (table 3).

Table 3.

Difference in PHQ-9 items at 6 months

| Variables | Intervention (n=333) n (%) |

Control (n=350) n (%) |

P values |

| PHQ-9 item 1: little interest or pleasure in doing things | 26 (7.8) | 85 (24.3) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 item 2: feeling down, depressed or hopeless | 43 (12.9) | 132 (37.7) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 item 3: trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 44 (13.2) | 119 (34.0) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 item 4: feeling tired or having little energy | 67 (20.1) | 187 (53.4) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 item 5: poor appetite or overeating | 25 (7.5) | 60 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 item 6: feeling bad about yourself—or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 17 (5.1) | 35 (10.0) | 0.016 |

| PHQ-9 item 7: trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 10 (3.0) | 23 (6.6) | 0.030 |

| PHQ-9 item 8: moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or so fidgety or restless that you have been moving a lot more than usual | 4 (1.2) | 8 (2.3) | 0.281 |

| PHQ-9 item 9: thoughts that you would be better off dead, or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 0.694 |

PHQ-9 item 9 relating to suicidality.

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

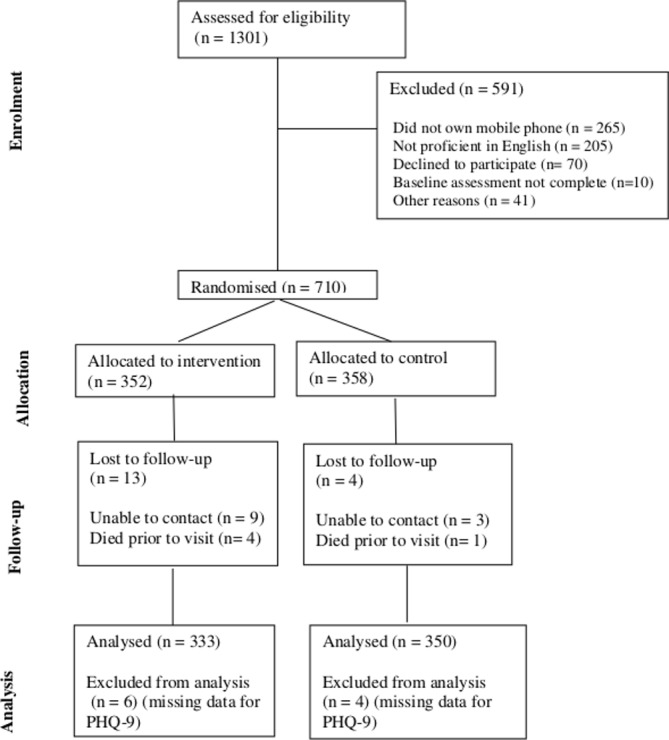

Figure 2 reports the treatment effect on PHQ-9 scores at 6 months by patient subgroup. The RR of being depressed after treatment compared with not being treated was consistent across patient subgroups: age, sex, education, body mass index, physical activity, current smoking, current drinking and history of depression, diabetes and hypertension (figure 2 and online supplementary table S2). The mental health component score of the SF-12 was significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the control group at 6 months (online supplementary table S3). The rates of PHQ-9 ≥5 among people with a history of depression were 4/44 (9.1%) vs 29/62 (46.8%) in intervention vs control (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.51, p<0.001), and were 17/289 (5.9%) vs 57/288 (19.8%) among others (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.50, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Treatment effects on Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores ≥5 at 6 months, by patient subgroup. BMI, body mass index; RR, relative risk.

Discussion

In the TEXT ME trial, we found that a lifestyle-focused cardiovascular secondary prevention programme delivered via text message, and not specifically targeting depression or other abnormal mood symptoms, resulted in fewer symptoms of depression at 6 months in participants receiving the texting intervention. There were 75% fewer patients reporting PHQ-9 scores over 5 in the intervention group and this proportional reduction was similar across different patient groups and somewhat unexpected given the lack of therapeutic content provided in the intervention. This size of difference is consistent with one depressive symptom that occurred nearly every day now only occurring several days a week, or reducing from more than half the days of the week to not at all; or alternatively the cessation of two symptoms that previously occurred several days a week.

A recent systematic review assessing the impact of text messaging interventions in individuals with mental health disorders suggested that the interventions might be effective in improving mental health outcomes (Box 1).17 However, the evidence for mHealth interventions in lowering depressive symptoms in patients with CHD, or in patients with other chronic health conditions is limited. The Care Assessment Platform for Cardiac Rehabilitation29 smart-phone-based intervention conducted in 120 patients with postmyocardial infarction, in 2009, included a comprehensive package of health and exercise monitoring, motivational and educational material delivery via text messaging and weekly mentoring consultations. It demonstrated non-significant reductions in psychological distress at 6 weeks (measured by Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale30, mean difference 1.85, 95% CI −0.11 to 3.8, p=0.1 and DASS-depression score, mean difference 0.90, 95% CI −0.77 to 2.57, p=0.3). Attendance in cardiac rehabilitation programmes have been shown to be associated with decreased symptoms of depression, and improved psychological well-being.31 Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy support programmes have also been shown to have potential in reducing depressive symptoms.32 33 With increasing use of mobile phones, text messaging has the potential to support cardiac rehabilitation and reduce the burden of cardiovascular diseases and depression.34

Box 1. Panel: research in context.

Systematic review

Systematic reviews of randomised controlled studies of mobile phone technologies for health behaviour change and disease management suggest that text messaging interventions might be useful for self-management of chronic diseases.11 Another systematic review of seven studies measuring the impact of text messaging in mental health reported that five studies had significant improvements in a variety of psychiatric and social functioning assessments.17 These studies suggest mobile phone text messaging programme has potential to support management of patients with mental illness.

Interpretation

The results of the TEXT ME trial suggest that provision of a text message-based intervention focused on lifestyle change among people with coronary heart disease was associated with less mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms at 6 months. These results suggest that text messaging might be a low-cost and scalable intervention to address the development of depression in patients with cardiovascular diseases.

In addition to the main effects on clinical outcomes of TEXT ME,19 the additional benefit of TEXT ME in reducing depressive symptoms at 6 months make it a very appealing low-cost strategy for patients with CHD. Depression is associated with worse health outcomes in patients with CHD.35 36 Poor health behaviours, such as smoking, non-adherence to prescribed medications and lifestyle changes are observed in patients with depression.37 Previous studies have suggested association of depression with quality of life.38 In our trial, quality of life—mental component summary scores were significantly lower in the intervention group compared with control group. These results should be interpreted cautiously because medication use can be a marker of depression, and our trial did not collect information on dose and duration of medication use for depression. It is possible that the improvements in behavioural risk factors in TEXT ME may have been in part mediated by improvements in psychological well-being. From our qualitative evaluation,21 participants in TEXT ME felt supported and engaged, and this is likely to contribute to the mechanisms that explain the reduction in depressive symptoms. It is also possible that the focus on improving lifestyle behaviours in TEXT ME contributed to differences in depressive symptoms as maintaining a healthy lifestyle is a key component of many depression management programmes.39

The strengths of this trial is the parallel-group, prospective, randomised controlled design and a relatively large sample size. With respect to limitations, it is a single-centre study, and the findings need to be replicated in other centres and populations. The analysis is a substudy and secondary analysis of the main TEXT ME trial and baseline measures of PHQ-9 were not included. The PHQ-9 was designed as a screening tool for depression and depressive symptoms. We did not confirm the presence of depression in trial participants using the gold standard semi-structured psychiatric interview. However, self-reported depression scores are highly correlated with the diagnosis of clinical depression and the PHQ-9 ≥5 cut point has good sensitivity (82%) and specificity (81%) when used with patients with CHD.26 While we did not assess depressive symptoms at baseline, randomisation ensured that most patient characteristics were distributed evenly between groups.

A previous study in Denmark, of 19 520 patients with acute coronary syndrome reported the prevalence of depression 15%–20%.40 A meta-analysis in patients with heart disease reported that the risk of mortality was two times higher in people with a history of depression.38 Our trial showed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was lower in the intervention group compared with the control group among those with a history of depression. While depression is recognised as important to manage in patients with chronic disease, there are few mechanisms available to help prevent the development of depression in patients at risk. The findings of this studysuggest the exciting potential of a simple and potentially scalable text message-based intervention to reduce mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms in this population. Addressing depressive symptoms early may be key to supporting patients in achieving multiple changes in risk factor behaviour.

In summary, this study demonstrates that provision of a text message-based intervention focused on lifestyle change among people with CHD was associated with a significantly lower frequency of mild-to-moderate depression symptoms at 6 months in the intervention group compared with controls. These results suggest that text messaging might be a low-cost and scalable intervention to prevent the development of depression in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Further research is needed to determine whether a text messaging programme can prevent the development of depression in patients with CHD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Westmead Hospital Cardiologists for supporting the recruitment and TEXT ME program development at Westmead Hospital.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drsislam

Contributors: CKC and SMSI had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. Study concept and design: CC, MLH, JR, AR. Analyses and interpretation of data: SMSI, CKC, SS, MH. Drafting of the manuscript: SMSI, CKC, MLH, CK, SS, KR. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. The first and the corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This work was supported by peer-reviewed grants from the National Heart Foundation of Australia Grant-in-Aid (G10S5110) and a BUPA Foundation Grant. CKC is funded by a Career Development Fellowship co-funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1033478) and National Heart Foundation (11S6016) and Sydney Medical Foundation Chapman Fellowship. SMSI is supported by a Senior Research Fellowship funded by Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition (IPAN), Deakin University and has received funding from High Blood Pressure Research Council of Australia. JR is funded by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1061793) co-funded with a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (G160523). MLH is funded by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship, Level 2 (100034: 2014–2017).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Western Sydney Local Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Patient-level data and statistical code available from the corresponding author at reasonable request. Consent for data sharing was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

References

- 1. Bradley SM, Rumsfeld JS. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2015;25:614–22. 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. . Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA 1995;274:1511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullivan MD, LaCroix AZ, Spertus JA, et al. . Five-year prospective study of the effects of anxiety and depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:1135–8. 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01174-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, et al. . Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. The Lancet 2003;362:604–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14190-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meijer A, Conradi HJ, Bos EH, et al. . Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of 25 years of research. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:203–16. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalal HM, Zawada A, Jolly K, et al. . Home based versus centre based cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:b5631 10.1136/bmj.b5631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on depression and its associated mortality. Am J Med 2007;120:799–806. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valencia HE, Savage PD, Ades PA. Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation in Underserved Populations. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2011;31:203–10. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e318220a7da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharpe M, Walker J, Holm Hansen C, et al. . Integrated collaborative care for comorbid major depression in patients with cancer (SMaRT Oncology-2): a multicentre randomised controlled effectiveness trial. Lancet 2014;384:1099–108. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61231-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patel V, Weobong B, Weiss HA, et al. . The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:176–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. . The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001362 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thakkar J, Kurup R, Laba TL, et al. . Mobile telephone text messaging for medication adherence in chronic disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:340–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shariful Islam SM, Niessen LW, Ferrari U, et al. . Effects of mobile phone sms to improve glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in Bangladesh: a prospective, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2015;38:e112–e113. 10.2337/dc15-0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev 2010;32:56–69. 10.1093/epirev/mxq004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richmond SJ, Keding A, Hover M, et al. . Feasibility, acceptability and validity of SMS text messaging for measuring change in depression during a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:1 10.1186/s12888-015-0456-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agyapong VI, Ahern S, McLoughlin DM, et al. . Supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder: single-blind randomised trial. J Affect Disord 2012;141:168–76. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson T, Simpson S, Hughes C. Text messaging interventions for individuals with mental health disorders including substance use: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2016;243:255–62. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chow CK, Redfern J, Thiagalingam A, et al. . Design and rationale of the tobacco, exercise and diet messages (TEXT ME) trial of a text message-based intervention for ongoing prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with coronary disease: a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000606 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chow CK, Redfern J, Hillis GS, et al. . Effect of lifestyle-focused text messaging on risk factor modification in patients with coronary heart disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:1255–63. 10.1001/jama.2015.10945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–87. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Redfern J, Santo K, Coorey G, et al. . Factors influencing engagement, perceived usefulness and behavioral mechanisms associated with a text message support program. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163929 10.1371/journal.pone.0163929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Redfern J, Thiagalingam A, Jan S, et al. . Development of a set of mobile phone text messages designed for prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:492–9. 10.1177/2047487312449416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) analysis guide. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Müller-Nordhorn J, Kulig M, Binting S, et al. . Change in quality of life in the year following cardiac rehabilitation. Qual Life Res 2004;13:399–410. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018473.55508.6a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stafford L, Berk M, Jackson HJ. Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:417–24. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McManus D, Pipkin SS, Whooley MA. Screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease (data from the Heart and Soul Study). Am J Cardiol 2005;96:1076–81. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haddad M, Walters P, Phillips R, et al. . Detecting depression in patients with coronary heart disease: a diagnostic evaluation of the PHQ-9 and HADS-D in primary care, findings from the UPBEAT-UK study. PLoS One 2013;8:e78493 10.1371/journal.pone.0078493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Varnfield M, Karunanithi M, Lee CK, et al. . Smartphone-based home care model improved use of cardiac rehabilitation in postmyocardial infarction patients: results from a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2014;100:1770–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Slade T, Grove R, Burgess P. Kessler psychological distress scale: normative data from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011;45:308–16. 10.3109/00048674.2010.543653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2015;351:h5000 10.1136/bmj.h5000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Griffiths KM, Farrer L, Christensen H. The efficacy of internet interventions for depression and anxiety disorders: a review of randomised controlled trials. Med J Aust 2010;192:S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glozier N, Christensen H, Naismith S, et al. . Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with mild to moderate depression and high cardiovascular disease risks: a randomised attention-controlled trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e59139 10.1371/journal.pone.0059139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chow CK, Ariyarathna N, Islam SM, et al. . mHealth in cardiovascular health care. Heart Lung Circ 2016;25:802–7. 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, et al. . Depression and cardiac disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2013;2013:1–14. 10.1155/2013/695925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frenneaux MP. Autonomic changes in patients with heart failure and in post-myocardial infarction patients. Heart 2004;90:1248–55. 10.1136/hrt.2003.026146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Whooley MA, de Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, et al. . Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA 2008;300:2379–88. 10.1001/jama.2008.711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, et al. . Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA 2003;290:215–21. 10.1001/jama.290.2.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beyondblue information paper - e- health programs july 2013. 2013. https://www.Beyondblue.Org.Au/get-support/treatment-options/other-sources-of-support.

- 40. Osler M, Mårtensson S, Wium-Andersen IK, et al. . Depression after first hospital admission for acute coronary syndrome: a study of time of onset and impact on survival. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183:218–26. 10.1093/aje/kwv227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022637supp001.pdf (477.1KB, pdf)