Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess if the reported provision of a coordinator was associated with time to first return to work (RTW) and first full RTW among sick-listed employees who participated in different rapid-RTW programmes in Norway.

Design

The study was designed as a cohort study.

Setting

Rapid-RTW programmes financed by the regional health authority in hospitals and Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration in Norway.

Participants

The sample included employees on full-time sick leave (n=326) who participated in rapid-RTW programmes (n=43), who provided information about the coordination of the services they received. The median age was 46 years (minimum–maximum 21–67) and 71% were female. The most common reported diagnoses were musculoskeletal (57%) and mental health disorders (14%).

Interventions

The employees received different types of individually tailored RTW programmes all aimed at a rapid RTW; occupational rehabilitation (64%), treatment for medical or psychological issues, including assessment, and surgery (26%), and follow-up and work clarification services (10%). It was common to be provided with a coordinator (73%).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Outcomes were measured as time to first RTW (graded and 100%) and first full RTW (100%).

Results

Employees provided with a coordinator returned to work later than employees who did not have a coordinator; a median (95% CI) of 128 (80 to 176) days vs 61 (43 to 79) days for first RTW, respectively. This difference did not remain statistically significant in the adjusted regression analysis. For full RTW, there was no statistically significant difference between employees provided with a coordinator versus those who were not.

Conclusions

The model of coordination, provided in the Norwegian rapid-RTW programmes was not associated with a more rapid RTW for sick-listed employees. Rethinking how RTW coordination should be organised could be wise in future programme development.

Keywords: return to work, occupational rehabilitation, sick leave, return to work coordination, return to work programs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is strengthened by use of register data on sickness absence.

This study is strengthened by the number of included employees.

The study could be strengthened with a smaller difference in numbers between employees with/without a coordinator.

Introduction

Prolonged sick leave can lead to permanent work disability. Work disability gives health, social and economic consequences for the worker, employer, as well as for society.1 Therefore, interventions facilitating a rapid return to work (RTW) are of importance both at an individual and at a socioeconomic level.1 The most common diagnostic groupings that cause sick leave in Norway are musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and mental disorders, which constitute approximately 40% and 20% of the total number of lost sick leave days, respectively.2 This is in line with other Western countries.1 3

To prevent permanent work disability, there has been increasing focus on the role of coordination of RTW processes and RTW programmes. RTW coordinators are well established as a part of RTW programmes in many Western countries.4 Insurers, employers or governmental agencies often employ the coordinators.5 In Norway, however, there are no formal guidelines or requirements for RTW coordinators. Still, persons in need for long-lasting and coordinated services within healthcare and social services have a statutory right for an Individual plan, a management tool for holistic coordination, administered by a coordinator.6 7 Furthermore, the government has implemented a coordination reform seeking to offer service users more comprehensive and continuous services.8 This reflects the government’s expectation that RTW programmes cooperate and coordinate their services across stakeholders and arenas. In addition, several initiatives to promote rapid RTW have been implemented both in the workplace arena and towards RTW programmes.9–11 Our recent study of the rapid-RTW programme, the largest RTW programme in Norway, revealed that approximately two-thirds of the employees in the programme had a coordinator. However, these coordinators mainly coordinated services within their own programmes, not between the intervention arenas (ie, workplace, social insurance and healthcare), referred to as horizontal integration.12 13 Furthermore, most of the employees with a coordinator received occupational rehabilitation services and were sick listed with MSD.12

Environmental interventions, such as adjustments and accommodation at the workplace have been found to be important for work reintegration among persons on sick leave due to MSD.14–16 Recent reviews have further documented the workplace as an important arena for RTW programmes directed at employees with mental health problems.17 18 Inclusion of the workplace in RTW programmes requires cooperation between several stakeholders across different arenas and levels of the health and welfare system.9 19 20 To enhance such cooperation, provision of RTW coordinators has been tested in several countries using various models for different groups of patients.21–26

Although the use of RTW coordinators has received increasing attention, there is some debate about the effect of the coordinators for RTW. A recent review conducted by Vogel et al concludes that there is no evidence that coordinated RTW programmes facilitate RTW compared with usual care.27 The coordinated RTW programmes in the review were defined as those identifying barriers to RTW and providing a designated coordinator to overcome these barriers through multiprofessional interventions, with several stakeholders involved and a face-to-face contact between employee and the coordinator.27 However, the included programmes were of various content, set-up and duration. Several of the studies included in the review were carried out in Norway,28 Sweden29 and Denmark,23 30 31 indicating the review’s27 relevance for the Scandinavian welfare states. The programmes described in the review are comparable to the rapid-RTW programme in Norway in regard to their complexity and the aim to promote RTW,12 27 32 but might differ in their focus on barriers to RTW and stakeholder cooperation that are reported lacking in the rapid-RTW programmes.12

In contrast, several studies have found that RTW coordination and provision of an RTW coordinator is positively association with time to RTW, and there is increasing evidence stating that these components are important in occupational rehabilitation.4 24 33–35 Furthermore, lack of coordination is associated with prolonged RTW, and some studies have reported that lack of coordination can complicate the RTW process.36 Reviews have documented RTW coordination as an important intervention predictor for RTW,15 34 37–41 and interventions including stakeholders at both rehabilitation programme and the workplace have been found to be successful for RTW.34 37 41 42 A recent review recommend implementation of RTW programmes towards sick-listed employees consisting of multiple components, where service coordination was one of three in addition to health-focused and work modification components.43

In light of these contradictions, the aim of this study was to assess if the reported provision of a coordinator was associated with a more rapid time to first RTW and first full RTW among sick-listed employees who participated in different public and private rapid-RTW programmes in Norway.

Methods

Design

The study was designed as a longitudinal cohort study of 326 employees on full-time sick leave, from 43 different rapid-RTW programmes in Norway.

Setting

The present study is one of several studies in an evaluation of the national RTW programme in Norway, the rapid-RTW project. The rapid-RTW programme is a national programme for patients on sick leave or at risk for sickness absence, aimed at reducing time to RTW and shorting the waiting time for treatment. To this date, the programme is the largest effort for promoting a fast and safe RTW in Norway.10 The national programme was implemented in 2007 and has an annual budget of Kr700 million (approximately $82 million). This initiative allowed for services to respond to tenders in order to get funding to develop and drift RTW programmes, and prioritise patients in a work relation for assessment, treatment and rehabilitation. The funding of the national programme will from 2018 be implemented in the health and welfare services’ ordinary budgets.44 The national programme includes approximately 200 different public and private RTW programmes, and is organised by the regional health authorities and the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV). The main types of programmes are (1) occupational rehabilitation, both inpatient and outpatient, (2) assessment and follow-up services by the social security system (NAV) and (3) medical or psychological treatment, including assessment and surgery.10 The organisation, content and intervention components, like the provision of a coordinator, were decided in each of the rapid-RTW programmes.

Data collection

All of the approximately 200 clinics or institutions offering rapid-RTW services were invited to participate in the study. Programmes that agreed to participate provided a local study coordinator, who recruited employees to the study in the period from February to December 2012. Both employees and their providers answered self-administered questionnaires about the employees’ health situation and the service they received, including the question ‘Did the program provide a person who tailored or coordinated your services?’. They could choose to answer on paper, or digitally. Data on sickness absence were retrieved from the Norwegian Social Insurance Register. Data on type of services employees received were retrieved from the Norwegian Patient Registry. The register data were linked to the self-reported data using 11-digit personal identification numbers. Each individual living in Norway is provided with a unique ID number that enables data from different registries to be linked.

Outcome measures

The outcome was defined as time to first RTW and first full RTW. Time was measured as days from when the employee started treatment at the RTW programme until the first day back at work, either partial or full job size (first RTW), and until the employee for the first time returned to work in the same job size they had before (first RTW or full RTW). These were therefore overlapping, and not mutually exclusive time frames. This way of measuring RTW is in line with previous research studies on time to RTW.45–47 The employees were followed for 360 days, and those who did not return within the follow-up time were censored in the analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in development of research question and outcome measure, nor design, recruitment or conduction of the study. The results will be made available through plain language synopsis and communicated to the public once published scientifically.

Participants

In total, 679 employees completed the questionnaire in the main cohort study. In the present study, 326 sick-listed employees who (1) answered the question regarding having a coordinator or not, (2) replied yes/no to the question of provision of a coordinator, (3) were on full-time sick leave at start of the RTW programme were included in the analyses. Reasons for exclusion were accordingly: (1) employees did not answer (n=185), (2) employees answered ‘do not know’ (n=120) and (3) employees were on graded sick leave (n=168). Some contributed to more than one reason.

The samples’ characteristics are presented in table 1. The employees’ median age was 46 years (minimum–maximum 21–67), and the majority had been sick listed before (96%). The most common diagnoses were MSD (57%) and mental health problems (14%). The most common type of RTW programme provided was occupational rehabilitation (63%), which included rehabilitation in hospitals and institutions, both inpatient and outpatient. These types of services are explained in earlier publications.10 12 Of the included participants, 73% were provided with a coordinator.

Table 1.

Participants

| Variable | Category | n | % |

| Gender | Female | 232 | 71 |

| Male | 94 | 29 | |

| Age* | Up to 30 years | 27 | 8 |

| 31–49 years | 175 | 54 | |

| 50 years + | 123 | 38 | |

| Marital status* | Living with partner | 219 | 68 |

| Not living with partner | 105 | 32 | |

| Educational | Elementary school (up to 9 years) | 38 | 12 |

| Level* | Upper secondary school (12 years) | 154 | 48 |

| University degree (up to 4 years) | 93 | 29 | |

| University degree (>4 years) | 35 | 11 | |

| Diagnosis | Musculoskeletal | 185 | 57 |

| Psychiatric | 45 | 14 | |

| Others incl. cardiovascular | 35 | 11 | |

| Cancer | 32 | 10 | |

| No diagnosis | 16 | 5 | |

| Unspecific | 13 | 4 | |

| Symptoms* | Pain at rest (yes) | 267 | 85 |

| Pain in activity (yes) | 277 | 89 | |

| Depressive mood (yes) | 244 | 78 | |

| Anxiety (yes) | 191 | 60 | |

| Type of RTW programme* | Occupational rehabilitation | 206 | 64 |

| Medical or psychological treatment, including assessment and surgery | 84 | 26 | |

| Follow-up and work clarification services | 32 | 10 | |

| Provided with a coordinator | Yes | 237 | 73 |

| Sector* | Public | 148 | 48 |

| Private | 158 | 52 | |

| History of sickness absence | Yes | 314 | 96 |

Data on all participants except *missing; age n=1, marital status n=2, educational level n=6, symptoms (pain at rest, n=10; pain in activity, n=15; depressive mood, n=11; anxiety, n=10), type of RTW programme n=4, sector n=20.

RTW, return to work.

Statistical analyses

Diagnoses were registered as International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) or International Classification of Diseases and related health problems (ICD) codes by the physician in the medical records, and categorised into the largest diagnostic groups ‘MSD’, ‘psychiatric disorders’, ‘cancer’ and ‘common/unspecific disorders’, other diagnosis (including neurological and heart disorders) or missing/no diagnosis, for the descriptive analysis. For the regression analysis, the categories common/unspecific, other diagnoses and missing/no diagnosis were collapsed. Time to first RTW and full RTW were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and crude differences between those who had and did not have a coordinator were assessed with log-rank tests. Stepwise Cox regression models were used to calculate the probability for returning to work (first RTW and first full RTW) for employees with a coordinator versus those who had not. Potential confounders for RTW were entered into the models. The confounders were identified in earlier studies in the literature,45 48–50 and included variables such as age, gender, educational level, marital status, diagnosis, self-reported symptoms (pain at rest, pain in activity, depressive mood and anxiety), sick leave history, household income and type of service. The results were expressed as HRs with 95% CIs. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant and all tests were two sided. The analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics V.24.

Results

Unadjusted results

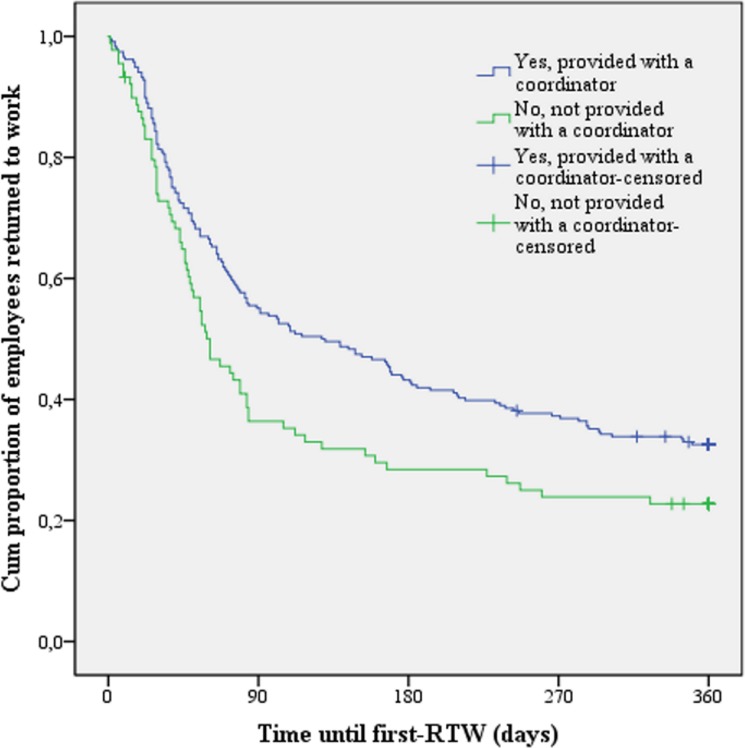

Having a coordinator was associated with delayed time to first RTW (figure 1). In the unadjusted analyses, employees who had a coordinator experienced a first RTW after 128 days (median; 95% CI 80 to 176) compared with 61 days (95% CI 43 to 79) for those who did not. This difference was statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of time until first RTW (days). RTW, return to work.

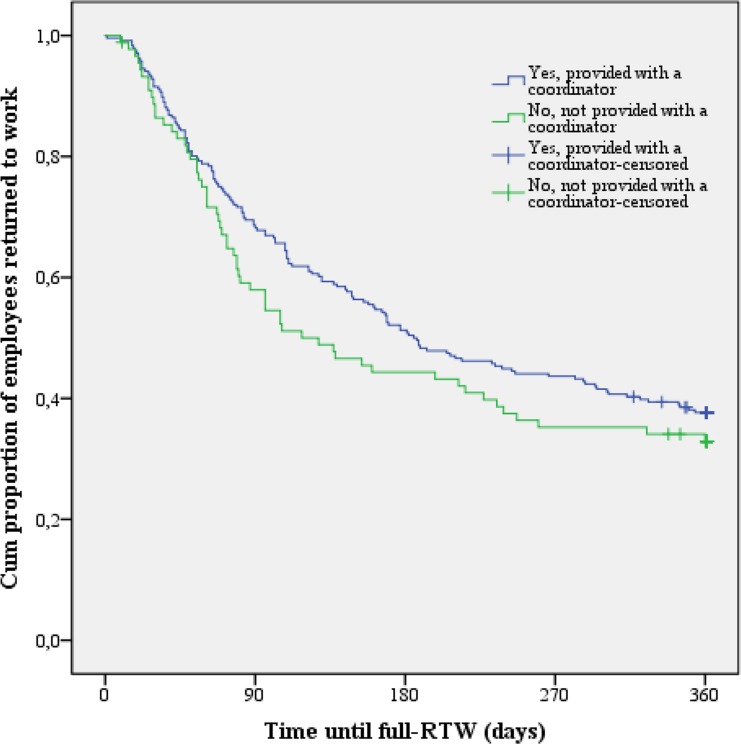

The unadjusted results for first full RTW showed that patients who had a coordinator returned to work a median of 57 days later than employees who did not have a coordinator; a median of 185 days (95% CI 137 to 233) vs 128 days (95% CI 72 to 184), respectively (figure 2). However, this difference did not reach the level of statistical significance (p=0.24).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of time until first full RTW (days). RTW, return to work.

Adjusted results

In the adjusted analysis, we controlled for age, gender, educational level, marital status, diagnosis, sick leave history, symptoms, household income and type of programme. Neither time to first RTW nor first full RTW was statistically significant in the adjusted analysis, with an HR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.10) for first RTW, and 0.82 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.22) for first full RTW (table 2).

Table 2.

The probability of experiencing a first RTW and full RTW

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| First RTW having a coordinator† |

0.70 | 0.53 to 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.51 to 1.10 | 0.14 |

| Full RTW having a coordinator† |

0.83 | 0.62 to 1.13 | 0.24 | 0.82 | 0.55 to 1.22 | 0.32 |

*Adjusted for age, gender, marital status, educational level, household income, diagnosis, type of RTW programme, symptoms (pain at rest, pain in activity, depressive mood and anxiety) and history of sickness absence.

†Ref not having a coordinator.

RTW, return to work.

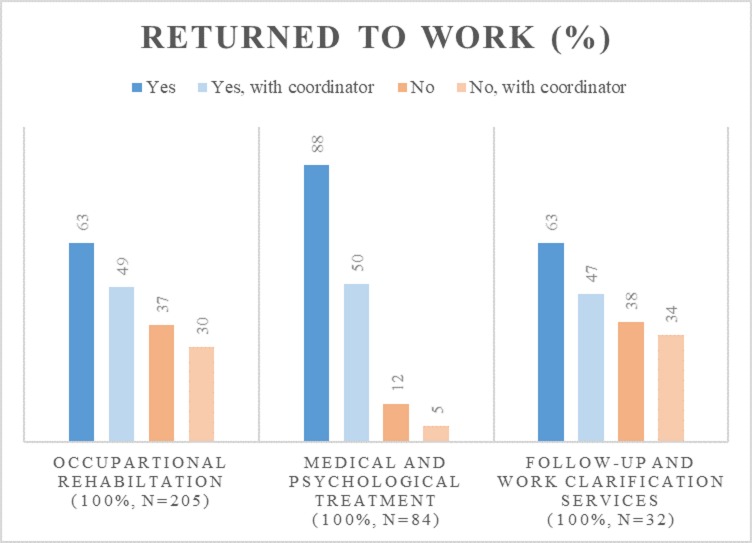

Type of RTW programme was a confounding factor between having a coordinator and RTW. In a stepwise adjusted analysis, time to first RTW remained statistically significant associated with having a coordinator when the other control variables were added to the model except type of programme (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.99). In order to understand differences between coordinator and type of programme in the model, time to first RTW for the different programme types was assessed. The difference in time to first RTW was statistically significant when comparing the programme types. Occupational rehabilitation had a median of 109 days before RTW (95% CI 52 to 166) and differed from assessment and follow-up programmes through NAV which had a median of 238 days (95% CI 192 to 284). Medical or psychological treatment including assessment and surgery had a median of 55 days (95% CI 37 to 73) and also differed from assessment and follow-up programmes through NAV. Figure 3 shows RTW rates (first RTW within 360 days yes/no) by type of programme. Of employees participated in medical or psychological treatment including assessment and surgery, 88% (n=74) had returned to work within the first year. The RTW rates for employees that participated in occupational rehabilitation or assessment and follow-up programmes through NAV were approximately 63%.

Figure 3.

Return to work (RTW) rates (first RTW within 360 days yes/no) by type of programme.

Furthermore, the provision of a coordinator varied between different types of RTW programmes. For the programme types occupational rehabilitation and assessment and follow-up programmes through NAV, 72.4% and 76%, respectively, were provided with a coordinator. For medical or psychological treatment, including assessment and surgery, 50% of the sick-listed employees were provided with a coordinator. Being provided with a coordinator were almost three times more likely in occupational rehabilitation and assessment and follow-up programmes through NAV than in medical or psychological treatment including assessment and surgery (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3 to 5.5).

Discussions

This study assessed whether provision of a coordinator was associated with time to first RTW and first full RTW in a cohort of sick-listed employees who participated in the rapid-RTW programme in Norway. The results show that having a coordinator seem to not enhance a more rapid RTW. Even though participants provided with a coordinator had a delayed first RTW compared with those who did not have a coordinator, the adjusted analyses revealed that the type of programme the sick-listed employee received might be the confounding factor for this delay. These two findings are discussed below.

First, the present study revealed that provision of a coordinator was not associated with a more rapid RTW for sick-listed employees who participated in the rapid-RTW programme in Norway. This result was somewhat unexpected. Even though there is some debate on the effect of coordination, having a coordinator has been found to increase the probability of returning to work in several previous studies.24 34 35 51 The results may have several explanations. One explanation might be that the coordinators in the present study were provided by the healthcare services,12 and they mostly coordinated their own services. Internationally, however, the coordinator is often provided by the insurers, employers or governmental agencies,5 making the coordinator more directly linked to the workplace. The workplace is one of the most important arenas for RTW programmes,15 16 since early contact with the workplace, as well as adaptations and support at the workplace, all are predictors for RTW.15 34 39–42 As such, the coordinators in the present study might differ from the RTW coordinators in other contexts, both in regard to who provides them and which of the intervention arenas they coordinate. A recent study from Norway found that adding a workplace focus in a multidisciplinary RTW programme in the specialist healthcare did not enhance RTW rates.28 The coordination provided in the study resulted in a weak connection between the RTW programme and the workplace.28 Hence, it might be possible that the model of coordination where the coordinator is placed in the specialist healthcare service, without real possibilities to coordinate and accommodate at the workplace, does not facilitate RTW.

Second, although an association between having a coordinator and delayed RTW was found in the univariate analysis, the delayed first RTW did not reach statistical significance when controlling for type of programme. The results furthermore shows that both frequencies of being provided with a coordinator and time to RTW varies based on type of RTW programme. This suggests type of programme as a confounding factor for the delay in RTW, and that the programme type explains more of the variation in RTW than being provided with a coordinator. Alternatively, the underlying cause for being referred to a specific type of RTW programme may explain even more of the variation found in this study. The distribution of coordinators varies across the different types of RTW programmes, and is most likely provided in assessment or follow-up services through NAV and occupational rehabilitation.12 Furthermore, treatment programmes are often provided to employees with specific MSD or mental disorders, whereas employees referred to occupational rehabilitation services often have more complex problems or situations.10 This study shows, regardless of whether the employees are provided with a coordinator, that the time to RTW doubles for employees receiving occupational rehabilitation compared with those receiving treatment, and furthermore quadruples for those receiving assessment and follow-up services through NAV. Therefore, one explanation for the delayed RTW for those provided with a coordinator may be that it is an expression of the complexity of the employees’ situation. A more complex situation for the sick-listed employee, in terms of, for example, comorbid diagnoses52 53 or difficulties in regard to psychosocial factors at work45 48 may work as barriers for RTW. Severity of health problems may as well complicate the RTW process, as shown in previous studies.37 38 Pain may indicate higher experienced severity, however, even though pain at rest is associated with provision of a coordinator in rapid-RTW programmes,12 pain is neither revealed as a predictor for provision of a coordinator,12 nor a significant explanatory factor for first or full RTW in this study. Another possible explanation is connected to the complexity of the RTW programmes.19 Some of the services include several interventions and components,10 and it is possible that the provision of a coordinator only adds to an already full schedule of interventions. For some groups, ‘brief interventions’ have been found to be just as effective as multidisciplinary rehabilitation services with several intervention components.30 54–56 Otherwise, if the services do not make room for enhancing contact with workplace and other stakeholders,12 the evidence-based active elements of coordination may be absent, leading to delayed RTW or no effect.

Nevertheless, the findings in this study are in line with a recent systematic review,27 as well as other studies on coordination from Scandinavia,28 30 supporting the finding that coordination might not facilitate RTW. Could this be due to the coordinator model used in the Scandinavian welfare system? This seems at least to have something to do with the type of coordination, where integration of services across levels and arenas are lacking.12 Furthermore, it might be that the groups receiving coordination is not well targeted. Still, we need to know more about who might benefit from having a coordinator. Coordination of RTW processes for employees with mental health problems has, for example, been studied to a small extent,27 and we do not know how coordination affects this group of sick-listed employees. Furthermore, there is a need to investigate and develop the roles, tasks and competencies of the RTW coordinator, within a Norwegian context. The Norwegian model for coordination where the link between the coordinator and the workplace is diffuse and not formalised in the RTW programmes10 12 57 58 should be further examined. Implications for practice and research, both in Norway and internationally, will be to develop new coordination models and implement such models in line with evidence, where a closer workplace connection seems to be a way forward.27 28

One of the strengths of this study is the high number of participants and the use of register data, which are both detailed and precise regarding sickness absence and diagnoses, as it is connected to the public social security benefit system. Approximately two-thirds of the patients in the study were provided with a coordinator, limiting the power to estimate the effect of not having a coordinator. Although the variable of provision of a coordinator is based on self-report from employees in present study, the time-to-first-RTW results from the analyses have been verified (median 102 days vs 79 days for those provided with coordinator vs not, respectively, with p=0.25) when compared with providers’ responses to the same variable (‘Did your service provide a coordinator for this patient?’). Furthermore, there was an association between having a coordinator and type of RTW programme. This makes it difficult to generalise the findings to all sick-listed employees participating in the rapid-RTW programmes as we were not able to distinguish between the effect of having a coordinator and a given programme. Additionally, the proportions of sick-listed employees due to MSD are higher than in the national statistics of Norway. However, since employees with MSD are the best-documented group of sick-listed benefiting from RTW coordination, this should be more an advantage regarding possibilities of revealing a difference between those provided with and those not provided with a coordinator. There is a possibility of selection bias in the study as the percentage of sick-listed employees with psychiatric issues and receiving psychological treatment is higher among the non-respondents. Fewer of employees with psychiatric issues is provided with a coordinator,12 meaning the power of analysis of this diagnose group might have been enhanced if more of these employees responded. However, employees with this diagnosis represent a small proportion of the total number of included participants. Therefore, inclusion of those employees would most likely not affect the main results decisively. Analysis of the full material of employees on full-time sick leave (n=546) shows some statistically significant differences between respondents and non-respondents on the question of provision of a coordinator. Non-respondents’ median age was slightly lower (44 years), and more had mental diagnosis (20%). In addition, fewer received occupational rehabilitation of the non-respondents (43%). If these were included, the proportion of employees with mental health disorders receiving treatment would most likely be larger, and this would most likely strengthen the present results.

Conclusion

This study revealed that employees participating in RTW programmes and who were provided with a coordinator had delayed time until they returned to work compared with those who did not have a coordinator. However, there was no association between provision of a coordinator and RTW when controlling for known confounders. As expected, type of programme seems to be a confounding factor, which explains more of the variation in RTW than being provided with a coordinator. The model of coordination provided in the Norwegian rapid-RTW programmes, mainly as part of occupational rehabilitation programmes in the healthcare, did not add to a more rapid RTW in this study. Hence, based on research literature as well as present study, RTW coordination where all three intervention arenas; the workplace, social services and healthcare are targeted should be further developed, before tested in rigorous studies with a design fitted for effect evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants, and the 43 rapid-RTW programmes for their valued contribution to this study. Especially thanks to the study coordinator in each of the RTW programmes. We would further like to thank the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs for cofunding the data collection of this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LSS has been involved in data collection, performed the analysis of the material and has been the main author of all parts of the drafted article. LAH has been involved in data collection, contributed to the discussion and has commented critically on the drafts. MCS has been involved in the analysis and commented critically on the drafts. WSS has contributed to the interpretation of data and commented critically on the drafts. RWA is the principal investigator and project manager of the rapid-RTW project. She designed the cohort study and managed and took part in all phases of this project. She planned the statistical analysis and commented critically on the drafts.

Funding: This work was supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Labour, Oslo Metropolitan University and Presenter—Making Sense of Science.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Participants in the study gave informed consent before inclusion. The data is handled anonymously and it is not possible to trace any personal information to individuals.

Ethics approval: The Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) approved this study with the reference number: 28988. Furthermore, the Norwegian Data Protection Authority gave consent to handle person- identified information, reference number: 13/00141-5/KEL.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to research ethical considerations, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. OECD. Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers: a synthesis of findings across OECD countries. Paris: OECD, 2010. 10.1787/9789264088856-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. NAV. Utviklingen i sykefraværet, 3. kvartal Sundell T, ed Arbeids- og velferdsdirektoratet, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. OECD. Sick on the job? Myths and Realities about Mental Health and Work. Mental Health and Work: OECD, 2012. 10.1787/9789264124523-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shaw W, Hong QN, Pransky G, et al. A literature review describing the role of return-to-work coordinators in trial programs and interventions designed to prevent workplace disability. J Occup Rehabil 2008;18:2–15. 10.1007/s10926-007-9115-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pransky G, Shaw WS, Loisel P, et al. Development and validation of competencies for return to work coordinators. J Occup Rehabil 2010;20:41–8. 10.1007/s10926-009-9208-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sosial- og helsedirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate of Health]. Individuell plan 2005: veileder til forskrift om individuell plan. Oslo: Sosial- og helsedirektoratet, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hagen R, Johnsen E. Styring Gjennom Samhandling: Samhandlingsreformen som Kasus In: Melby L, Tjora AH, eds Samhandling for helse. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet [Ministry of Health and Care Services]. Samhandlingsreformen: rett behandling - på rett sted - til rett tid St.meld. nr. 47 (2008-2009) Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aas RW. Workplace-based sick leave prevention and return to work. Exploratory studies [Ph.D. Thesis}: Karolinska Institutet, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aas R, Solberg A, Strupstad J. Raskere tilbake. Organisering, kompetanse, mottakere og forløp i 120 tilbud til sykmeldte. IRIS, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindoe P, Bakke Å, Aas RW. Avtalen for et inkluderende arbeidsliv. Virkemidler fra nasjonalt nivå til ledernivå i oppfølgingen av sykemeldte. Tidsskrift for Arbejdsliv 2006;8:68–89. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skarpaas LS, Haveraaen LA, Småstuen MC, et al. Vertical or horizontal Return to Work Coordination? The Rapid-RTW Cohort study. In review 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hvinden B. Divided against itself: a study of integration in welfare bureaucracy. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Oostrom SH, van Mechelen W, Terluin B, et al. A participatory workplace intervention for employees with distress and lost time: a feasibility evaluation within a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil 2009;19:212–22. 10.1007/s10926-009-9170-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HC, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;10:CD006955 10.1002/14651858.CD006955.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nastasia I, Coutu MF, Tcaciuc R. Topics and trends in research on non-clinical interventions aimed at preventing prolonged work disability in workers compensated for work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs): a systematic, comprehensive literature review. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:1841–56. 10.3109/09638288.2014.882418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nieuwenhuijsen K, Faber B, Verbeek JH, et al. Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev;23:CD006237 10.1002/14651858.CD006237.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pomaki G, Franche RL, Murray E, et al. Workplace-based work disability prevention interventions for workers with common mental health conditions: a review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil 2012;22:182–95. 10.1007/s10926-011-9338-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loisel P, Durand Marie-José, Berthelette D, et al. Disability Prevention. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 2001;9:351–60. 10.2165/00115677-200109070-00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steenstra I, Cullen K, Irvin E, et al. A systematic review of interventions to promote work participation in older workers. J Safety Res 2017;60:93–102. 10.1016/j.jsr.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Bongers PM, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: graded activity or workplace intervention or both? A randomized controlled trial. Spine 2007;32:291–8. 10.1097/01.brs.0000253604.90039.ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lander F, Friche C, Tornemand H, et al. Can we enhance the ability to return to work among workers with stress-related disorders? BMC Public Health 2009;9:372 10.1186/1471-2458-9-372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bültmann U, Sherson D, Olsen J, et al. Coordinated and tailored work rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial with economic evaluation undertaken with workers on sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil 2009;19:81–93. 10.1007/s10926-009-9162-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varatharajan S, Côté P, Shearer HM, et al. Are work disability prevention interventions effective for the management of neck pain or upper extremity disorders? A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) collaboration. J Occup Rehabil 2014;24 692–708. 10.1007/s10926-014-9501-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hubbard G, Gray NM, Ayansina D, et al. Case management vocational rehabilitation for women with breast cancer after surgery: a feasibility study incorporating a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:175 10.1186/1745-6215-14-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Poulsen OM, Aust B, Bjorner JB, et al. Effect of the Danish return-to-work program on long-term sickness absence: results from a randomized controlled trial in three municipalities. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:47–56. 10.5271/sjweh.3383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vogel N, Schandelmaier S, Zumbrunn T, et al. Return-to-work coordination programmes for improving return to work in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:CD011618 10.1002/14651858.CD011618.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Myhre K, Marchand GH, Leivseth G, et al. The effect of work-focused rehabilitation among patients with neck and back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine 2014;39:1999–2006. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindh M, Lurie M, Sanne H. A randomized prospective study of vocational outcome in rehabilitation of patients with non-specific musculoskeletal pain: a multidisciplinary approach to patients identified after 90 days of sick-leave. Scand J Rehabil Med 1997;29:103–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jensen C, Jensen OK, Christiansen DH, et al. One-year follow-up in employees sick-listed because of low back pain: randomized clinical trial comparing multidisciplinary and brief intervention. Spine 2011;36:1180–9. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181eba711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stapelfeldt CM, Christiansen DH, Jensen OK, et al. Subgroup analyses on return to work in sick-listed employees with low back pain in a randomised trial comparing brief and multidisciplinary intervention. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:112–12. 10.1186/1471-2474-12-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655–a55. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, et al. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:257–69. 10.5271/sjweh.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:607–31. 10.1007/s10926-005-8038-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nevala N, Pehkonen I, Koskela I, et al. Workplace accommodation among persons with disabilities: A systematic review of its effectiveness and barriers or facilitators. J Occup Rehabil 2015;25:432–48. 10.1007/s10926-014-9548-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Young AE, Wasiak R, Roessler RT, et al. Return-to-work outcomes following work disability: stakeholder motivations, interests and concerns. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:543–56. 10.1007/s10926-005-8033-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Stochkendahl MJ, et al. Factors affecting return to work after injury or illness: best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropr Man Therap 2016;24:32 10.1186/s12998-016-0113-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rinaldo U, Selander J. Return to work after vocational rehabilitation for sick-listed workers with long-term back, neck and shoulder problems: A follow-up study of factors involved. Work 2016;55:115–31. 10.3233/WOR-162387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Williams-Whitt K, Bültmann U, Amick B, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent disability from both the scientific and practice perspectives: A comparison of scientific literature, grey literature and stakeholder observations. J Occup Rehabil 2016;26:417–33. 10.1007/s10926-016-9664-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Briand C, Durand MJ, St-Arnaud L, et al. How well do return-to-work interventions for musculoskeletal conditions address the multicausality of work disability? J Occup Rehabil 2008;18:207–17. 10.1007/s10926-008-9128-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Franche RL, Baril R, Shaw W, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: optimizing the role of stakeholders in implementation and research. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:525–42. 10.1007/s10926-005-8032-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoefsmit N, Houkes I, Nijhuis FJ. Intervention characteristics that facilitate return to work after sickness absence: a systematic literature review. J Occup Rehabil 2012;22:462–77. 10.1007/s10926-012-9359-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, et al. Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions in Return-to-Work for Musculoskeletal, Pain-Related and Mental Health Conditions: An Update of the Evidence and Messages for Practitioners. J Occup Rehabil 2018;28:1–15. 10.1007/s10926-016-9690-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Regjeringen. Prop. 1 S (2017–2018). Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet [Ministry of Health and Care Services] www.regjeringen.no: Regjeringen, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haveraaen LA, Skarpaas LS, Aas RW. Job demands and decision control predicted return to work: the rapid-RTW cohort study. BMC Public Health 2017;17:154 10.1186/s12889-016-3942-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flach PA, Groothoff JW, Krol B, et al. Factors associated with first return to work and sick leave durations in workers with common mental disorders. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:440–5. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JH, Siemerink JC, et al. Quality of rehabilitation among workers with adjustment disorders according to practice guidelines; a retrospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2003;60 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):21i–5. 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Haveraaen L, Berg JE, Skarpaas LS, et al. Do psychosocial job demands, decision control and social support predict return to work after occupational rehabilitation or medical treatment? The rapid-RTW study. Work: A journal of Prevention, Assesment and rehabilitation 2016. 10.3233/WOR-152216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Selander J, Marnetoft SU, Bergroth A, et al. Return to work following vocational rehabilitation for neck, back and shoulder problems: risk factors reviewed. Disabil Rehabil 2002;24:704–12. 10.1080/09638280210124284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cornelius LR, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW, et al. Prognostic factors of long term disability due to mental disorders: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2011;21:259–74. 10.1007/s10926-010-9261-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schandelmaier S, Ebrahim S, Burkhardt SC, et al. Return to work coordination programmes for work disability: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2012;7:e49760–e60. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huijs JJ, Koppes LL, Taris TW, et al. Differences in predictors of return to work among long-term sick-listed employees with different self-reported reasons for sick leave. J Occup Rehabil 2012;22:301–11. 10.1007/s10926-011-9351-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Laisné F, Lecomte C, Corbière M. Biopsychosocial predictors of prognosis in musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of the literature (corrected and republished) *. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:1912–41. 10.3109/09638288.2012.729362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aas RW, Skarpaas LS. The impact of a brief vs. multidisciplinary intervention on return to work remains unclear for employees sick-listed with low back pain. Aust Occup Ther J 2012;59:249–50. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2012.01020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brox JI, Storheim K, Grotle M, et al. Systematic review of back schools, brief education, and fear-avoidance training for chronic low back pain. Spine J 2008;8:948–58. 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.07.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guzman J, Hayden J, Furlan AD, et al. Key factors in back disability prevention: a consensus panel on their impact and modifiability. Spine 2007;32:807–15. 10.1097/01.brs.0000259080.51541.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Skarpaas L, Berg J, Ramvi E, et al. Eksperters synspunkter på tilbudet til sykmeldte i Norge. Første runde av en delphi-studie. Ergoterapeuten 2017;60:78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Skarpaas LS, Ramvi E, Løvereide L, et al. Maximizing work integration in job placement of individuals facing mental health problems: Supervisor experiences. Work 2015;53:87–98. 10.3233/WOR-152218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.