Abstract

Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), an important sequela of preterm birth, is associated with long-term abnormalities of lung function and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Inflammation, inhibition of secondary septation and vascular maldevelopment play key roles in the pathogenesis of BPD. Human amnion epithelial cells (hAECs), stem-like cells, derived from placental tissues are able to modulate the inflammatory milieu and, in preclinical studies of BPD-like injury, restore lung architecture and function. Allogeneic hAECs may present a new preventative and reparative therapy for BPD.

Methods and analysis

In this two centre, phase I cell dose escalation study we will evaluate the safety of intravenous hAEC infusions in preterm infants at high risk of severe BPD. Twenty-four infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation will each receive intravenous hAECs beginning day 14 of life. We will escalate the dose of cells contained in a single intravenous hAEC infusion in increments from 2 million cells/kg to 10 million cells/kg. Further dose escalation will be achieved with repeat infusions given at 5 day intervals to a maximum total dose of 30 million cells/kg (three infusions). Safety is the primary outcome. Infants will be followed-up until 2 years corrected age. Additional outcome measures include a description of infants’ cytokine profile following hAEC infusion, respiratory outcomes including BPD and pulmonary hypertension and other neonatal morbidities including neurodevelopmental assessment at 2 years.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved on the June12th, 2018 by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Monash Health and Monash University. Recruitment commenced in August 2018 and is expected to take 18 months. Accordingly, follow-up will be completed mid-2022. The findings of this study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and at conferences.

Protocol version

5, 21 May 2018.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618000920291; Pre-results.

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, premature infant, cell therapy, stem cells, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A study to evaluate the safety of a potential novel preventative and reparative therapy for a significant neonatal morbidity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).

A study translating preclinical advances in cell therapy to the clinical arena.

Cytokine profiling and assessment of respiratory morbidity may inform the mechanism of action of human amnion epithelial cells and the design of future efficacy trials.

Given the phase I nature of the study, there is no comparator group.

Predicting and defining BPD in the study population is based on traditional but imperfect definitions.

Introduction

Owing to significant advances in neonatal intensive care, the survival of preterm infants is increasing, particularly those born prior to 29 weeks’ gestation. However, survival brings with it the risk of significant morbidity. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), the chronic lung disease unique to preterm infants, is an important morbidity associated with long-term impairments of both lung function and neurodevelopment. Despite advances in the care of preterm infants the rate of BPD in survivors has not changed over recent decades. In some instances, pulmonary outcomes in more recent cohorts of preterm infants have worsened.1 Children with BPD have impaired lung function that declines further in late adolescence.2 The trajectory into adulthood of infants born in the era of surfactant use remains unknown, but it is likely that these infants will be burdened with a greater risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in mid-life.3–6 Infants with BPD also have higher rates of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes, including cognitive impairment, speech and language difficulties, motor impairment, visual and auditory problems and behavioural difficulties, compared with infants without BPD.7 8

As neonatal medicine has evolved, the phenotype of BPD has changed. ‘Old’ BPD, described by Northway et al,9 was a disease affecting predominantly infants born <34 weeks. It was due to surfactant deficiency, ventilator induced trauma and high oxygen concentrations, and was characterised by heterogeneous lung injury with areas of atelectasis interspersed with pockets of hyperinflation. Airway smooth muscle proliferation, pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis were other key features. Today, the infants at greatest risk of BPD are born earlier, in the canalicular phase of lung development, before alveolar and distal capillary development commences. Disruption of this process by preterm birth and the pro-inflammatory environment created by the necessary neonatal intensive care interventions that follow result in the histopathology characteristic of ‘new’ BPD—abnormal angiogenesis and arrested alveolar development with larger, simpler alveoli.10 Currently, there is no preventative or reparative therapy for BPD. However, inflammation plays a key role in the disruption of vascular and alveolar development that characterises the condition. Targeting inflammation with new generation therapies, such as stem cells and stem-like cells, may offer some benefit for infants at risk of BPD.

The therapeutic application of stem cells has been hampered by concerns regarding the cells’ potential for tumour formation.11 This is particularly true of embryonic stem cells which are teratoma forming, but also of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs).11 In this regard, a systematic review and meta-analysis of intravascular MSC trials reports no increased risk of malignancy in the 321 participants in randomised controlled trials reducing these concerns in relation to MSCs.12 Another stem-like cell, human amnion epithelial cells (hAECs), also offer great promise for therapeutic application. hAECs are stem-like cells isolated, in the hundreds of millions, from the amniotic membrane of the human placenta. They have multilineage potential, low risk of allogeneic rejection given their limited expression of human leucocyte antigens (class IA and class II antigen) and are not teratogenic in small animal models.13 Specifically, hAECs have a stable phenotype after multiple passages14 supporting the consensus that the likelihood of hAECs forming tumours is extremely remote.15 In vivo models also support these in vitro observations. Tumour formation has not been described following the use of hAECs in animal models and amniotic membranes containing hAECs have been used for decades in wound healing16 without evidence of tumour formation. Clinical trials of systemic administration of hAECs have not been undertaken to date to allow an assessment of teratogenicity to the same degree as MSCs.

In animal models of diverse lung injuries hAECs both prevent injury and aid repair of established injury. For example, following bleomycin induced injury in a severe combined immunodeficiency murine model, hAECs reduced both acute inflammation, as evidenced by a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines and an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines, and reduced lung scarring, as evidenced by a reduction in collagen content.17 In an immunocompetent mouse model, hAECs prevented bleomycin-induced injury, improved lung function18 and accelerated repair.19 These preventative and reparative functions are dependent on host macrophages20 21 and T regulatory cells.22 23 In a murine model of BPD-like lung injury, hAECs mitigated lung inflammation and alveolar simplification, and prevented secondary pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy induced by antenatal inflammation and postnatal hyperoxia.24 In this model, the cells were most effective when given earlier. Similarly, in fetal sheep models of preterm lung injury, hAECs mitigated the injurious effect of both ventilation25 and inflammation,26 as evidenced by less collagen and elastin deposition, less fibrosis and normalisation of secondary septal crests, and restoration of a normal lung tissue to airspace ratio.25 26

The relative ease and abundance of cell isolation and collection, the apparent safety profile and lack of risk of rejection, and the preventative and reparative efficacy in diverse animal models of lung injury, present compelling evidence for the potential of hAECs as a preventative therapy for BPD.

Informed by a decade of in vitro and animal studies, the first-in-human trial to assess the safety of hAECs in preterm infants with established BPD was recently reported.27 Six infants, born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation with severe BPD were administered 1 million hAECs/kg by slow intravenous infusion. The first infant became bradycardic and hypoxic during the infusion. This was likely related to pulmonary microembolic phenomena. He recovered rapidly on stopping the infusion. Changes were made to the cell infusion protocol and the remaining five infants tolerated the infusion without any acute haemodynamic effects. While monitoring until 2 years of age continues, 6-month follow-up has revealed no adverse effects related to cell administration.

While that study has provided the essential first safety data, it is unlikely that a dose of 1 million hAECs/kg will be sufficient for a therapeutic effect. Based on pre-clinical studies,19–21 it is likely that a dose as high as 30 million cells/kg body weight, or higher, may be required for therapeutic effects. Such cell dosing is in accord with clinical trials assessing the utility of umbilical cord blood stem cells in children as a therapy for brain injury,28 cerebral palsy29 and autism.30 Prior to undertaking any efficacy trials, the next necessary step in the assessment of hAECs as a possible preventative therapy for BPD is to ensure the safety of higher doses of hAECs.

Accordingly, here we describe a dose escalation study to evaluate the safety of intravenously administered hAECs in doses of up to 30 million hAECs/kg in infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation at high risk of developing BPD. The aim of our study is to evaluate the tolerability of intravenous hAEC at a dose equivalent to that which has shown efficacy in our pre-clinical models.19 20 24

Methods and analysis

This study is a two centre, dose escalation safety trial. Twenty-four infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation, at risk of severe BPD, will each receive intravenous hAEC infusions during the third and fourth weeks of life. Infants will be recruited from two neonatal intensive care units in Melbourne, Australia: Monash Newborn at Monash Children’s Hospital and The Royal Women’s Hospital. Safety is the primary outcome and adverse events will be recorded. There is no control group.

Sample size

The sample size of 24 infants is based on other dose escalation trials in stem cell therapies. Nine infants born at less than 30 weeks’ gestation were recruited to a phase I study using MSCs (Pneumostem) to prevent BPD.31 The dose of cells administered increased from 10 million cells/kg to 20 million cells/kg after the first three infants were successfully treated. A phase I dose escalation trial using intravenous MSCs to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults recruited nine patients, treating three patients at each dose of 1 million cells/kg, then 5 million cells/kg and then 10 million cells/kg.32

There will be six dose cohorts (see Intervention below). The cohorts receiving a single infusion of hAECs/kg will each comprise three infants, in keeping with the studies described above.31 32 The cohort size will increase to six infants for cohorts that receive multiple infusions to (1) more robustly demonstrate safety at a dose more likely to be efficacious and (2) remain consistent with other cell therapy dose escalation trials.31

Patient selection

Infants will be deemed at high risk of severe BPD and eligible for inclusion if on day 14 of life they require an FiO2≥0.25 while mechanically ventilated by an endotracheal tube, or an FiO2≥0.35 while receiving non-invasive respiratory support to maintain oxygen saturations within the target range of 91%–95%.

As novel therapeutic agents with uncertain safety profiles are studied, it is imperative that infants at high risk of BPD are selected in order to justify the uncertain risks of participation. Our inclusion criteria are based on a cohort study of 122 infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation cared for in the recruiting neonatal units. Infants receiving mechanical ventilation via an endotracheal tube with an FiO2≥0.25 or non-invasive respiratory support with an FiO2≥0.35 on day 14 of life had either severe BPD at 36 weeks PMA or died prior to discharge with a positive predictive value of 92% and a specificity of 94%. (Baker EK and Davis PG. BPD Outcome Estimator; Utility in Predicting Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. 2018.) Severe BPD, the need for an FiO2≥0.30 and/or positive pressure support at 36 weeks post menstrual age (PMA), was described using established National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) definitions.33

Infants will be ineligible if the treating clinical team deem death imminent or are no longer providing intensive care, or if the infant has a significant congenital anomaly including but not limited to congenital cardiac disease, airway malformation or severe neurological abnormality.

hAEC infusion preparation

Donor screening

Following written informed consent, placentae are donated by healthy women with uncomplicated pregnancies undergoing elective caesarean section at term at Monash Health, Victoria, Australia. Women are screened on the day of donation by serological testing for HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B surface antigen, human T lymphotropic virus and syphilis, and nucleic acid testing for HIV, HCV and hepatitis B virus. Testing is performed by an independent National Association of Testing Authority (NATA) Australia accredited laboratory (National Reference Laboratory, Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia).

Cell collection

Placentae are collected at the time of surgery and processing commences within theatre. The amnion is peeled from the chorion, rinsed for 2 min in sterile saline and transferred to an antibiotic-antimycotic solution (cefazolin 1 g/L, AFT Pharmaceutical, North Rhyde, New South Wales, Australia, https://www.aftpharm.com; gentamicin 80 mg/L, Pfizer, New York City, New York, https://www.pfizer.com; amphotericin B 50 mg/L, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia, https://www.bms.com) for 2 min. The amnion is then transferred in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Media (Cat. No. 10566016, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Scoresby, Victoria, Australia, https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home.html) supplemented with antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Cat. No. 15240062, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to the cell isolation facility within Monash Health Translation Precinct’s Cell Therapy and Regenerative Medicine Platform. Within this facility hAECs are isolated as previously described.34

Product release

hAECs are released for clinical use only when the following criteria are met:

Cell viability >80% as determined by trypan blue exclusion test at the time of cryopreservation.

Cell isolate is free of microbial contamination after 14 days of culture in anaerobic and aerobic conditions, testing performed by NATA-accredited laboratory, St Vincent’s Hospital Pathology, Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia.

Cells isolated are >96% EpCAM+, <1% CD105, <1% CD45+, <1% CD90 as determined by flow cytometry.

Infusion preparation

On the day of infusion, hAECs will be retrieved from liquid nitrogen storage and thawed using a pre-warmed heat block for approximately 2 min until a small ice crystal remains. The hAECs will be washed with saline and centrifuged at 350 g for 5 min prior to resuspension in 5% dextrose with 2% albumin at the final desired concentration. The hAECs will be suspended at a concentration 25% greater than the desired post filter concentration to allow for cell loss.

Post infusion testing

Following administration of the infusion, a post filter sample of the hAEC suspension will be collected to determine cell viability (using a trypan blue exclusion test) and a cell count will be performed.

Intervention

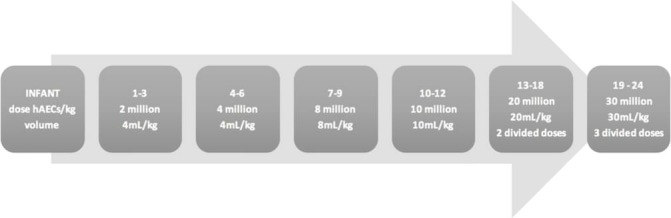

The first 12 infants will each receive a single intravenous dose of hAECs administered between days 14 and 18 of life, inclusive. The dose of hAECs in a single infusion will start at 2 million cells/kg and increase in increments to 10 million cells/kg, escalating after every third infant. Dose escalation will be achieved in the final 12 infants by giving repeated doses, at 5-day intervals, of 10 million hAECs/kg to achieve a maximum dose of 30 million cells/kg. The dose schedule is outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dose escalation schedule. Infants 1–12 will receive a single infusion; infants 13–18 and 19–24 will receive 2 and 3 infusions, respectively, of 10 million hAECs/kg/infusion. hAECs, human amnion epithelial cells.

Infants 13–18 and 19–24 will receive two or three infusions to achieve dose escalation to 20 million hAECs/kg and 30 million hAECs/kg, respectively. The dose to be delivered in a single infusion is limited to a maximum of 10 million hAECs/kg by (i) the volume (mL/kg) we could infusion over 1 hour without impacting too greatly on infants’ fluid status, (ii) limiting the cell concentration to 1 million hAECs/mL, so as to remain more dilute than the 2 million hAECs/mL infusion that was not tolerated during the first-in-human trial27 and (iii) limit the duration of the infusion to 1 hour given the potential for cell attrition.

The adverse event, bradycardia and hypoxia during hAEC infusion, observed in the first-in-human trial27 was likely due to cell clumping and resultant micro-pulmonary emboli. Changes were made to the infusion protocol during that study; the suspension was diluted from 2 million hAECs/mL to 0.25 million hAECs/mL, a 200 μ paediatric transfusion filter was added, the infusion was given over 30 min via a syringe pump rather than a slow manual infusion and the suspension was gentle agitated on a rocking platform for the duration of the infusion. To protect against embolic phenomenon our current infusion procedure replicates these protocol modifications. The hAEC infusion will be given via a peripheral intravenous cannula over 1 hour using a 200 μ paediatric transfusion filter and syringe pump. The cell suspension will be gently agitated on a rocking platform throughout the infusion. The concentration of cells will start at 0.5 million hAECs/mL for the first cohort of three babies then increase to 1 million hAECs/mL for the remaining infants. This concentration remains lower than the concentration at which the adverse event was observed. Infants receiving multiple infusions will have hAECs sourced from the same donor.

A first cell infusion ‘window’ will begin on day 14 of life and extend to day 18 of life, inclusive. During this 5 day period all infants will be given their first hAEC infusion. This will be the only cell infusion for infants 1–12. For infants 13–18 and 19–24, it will be the first of two or three infusions, respectively. The infusion will be given at the earliest practical time during the treatment window allowing for safety considerations and delays afforded by the conditions described below.

hAEC infusion will be delayed in infants with the following conditions/treatments until resolution of the condition or cessation of the treatment. Should this condition/treatment not resolve/cease during the 5 day treatment window, the infant will be deemed ineligible.

Current medical treatment or treatment within the preceding 24 hours for a patent ductus arteriosus.

Surgery in the preceding 72 hours or planned in the next 72 hours.

Receiving antibiotics for active sepsis, defined as either culture proven, or culture negative but clinically suspected.

Necrotising enterocolitis, ≥stage II modified Bell’s staging criteria.

Primary outcome

Safety is the primary outcome. It will be defined by the occurrence of adverse events as defined below.

Monitoring during infusion

Infants will be observed for 2 hours prior to hAEC infusion to determine their baseline cardiorespiratory status and establish acceptable parameters for fluctuations during the infusion. The monitoring schedule for the 2 hours prior to the infusion and the 24 hours post is outlined in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Monitoring schedule for 2 hours pre-infusion and 24 hours post infusion. HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; SpO2, oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry.

Infants, as a result of their prematurity, are likely to remain inpatients in intensive and special care nurseries for at least 2–3 months following the intervention. The routine clinical care afforded infants over this time will serve as monitoring for adverse events. Routine care will include the following:

Continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring while receiving respiratory support.

Physical examination, daily while infants remains on respiratory support.

Anthropometry (weekly weight, head circumference, length).

Documentation of respiratory support requirements.

Chest radiograph, as clinically indicated but anticipated weekly at a minimum while infants are mechanically ventilated.

Blood gas analysis, as determined by clinical team.

Cranial ultrasound, as per clinical practice of neonatal unit but anticipated to be a minimum of two cranial ultrasounds post infusion prior to discharge.

In addition to routine care, infants will also receive fortnightly liver and renal function tests until discharge to assess for signs of organ damage related to allogeneic rejection, and imaging (abdominal ultrasound and MRI brain) at 36 weeks’ PMA to term to assess for tumour formation.

Monitoring post discharge

Following discharge infants will be assessed at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months corrected age. Assessment will focus on general health including growth parameters and physical examination, reporting of adverse events and medication usage. Neurodevelopmental assessment will be performed using the Bayley Scales of Infants and Toddler Development at 2 years corrected age. Surveillance for tumour formation will continue as outlined in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Planned surveillance for tumour formation. Abdo US, abdominal ultrasound; CA, corrected age; CXR, chest X-ray; PMA, postmenstrual age.

Defining adverse events

Adverse events will be defined as follows:

Cardiorespiratory instability and/or anaphylaxis within 72 hours of hAEC infusion.

Any event requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- Escalation of respiratory support.

- Intubation of an infant receiving non-invasive respiratory support at the time of hAEC infusion.

- Change to high frequency oscillatory ventilation in an infant receiving conventional ventilation at the time of hAEC infusion.

Fluid bolus or initiation/escalation of inotropic support.

Any sustained change of 30% or more from baseline in vital signs.

Temperature instability, temperature ≤36°C or ≥38°C.

Development of cardiac arrhythmia.

Infection within 72 hours of hAEC infusion.

Culture proven bacterial, fungal or viral infection.

Culture negative but clinically suspected infection.

Allogeneic rejection

Impaired neurological, hepatic, renal or gastrointestinal function evidenced by: new onset jaundice, elevation of hepatic enzymes; persistent feed intolerance not explained by other pathology; seizures, altered neurological state; oliguria, anuria, polyuria and biochemical renal dysfunction.

Tumour formation

Features of tumour formation as evidenced by development of mass lesion/s on physical examination or radiological investigation.

Local site reaction

Erythema, oedema, extravasation at site of peripheral intravenous catheter site.

Dose limiting toxicity

Dose limiting toxicity will be defined by the occurrence of serious adverse events, as described above, during and for the 72 hours following hAEC infusion.

Safety monitoring

An independent data safety monitoring board (DSMB) has been established. A report will be provided to the DSMB, and to the HREC, within seven working days after each dose cohort (three babies for the first four cohorts and six babies for the last two cohorts) has received the intervention. Written permission from the DSMB will be sought prior to recruitment of the next dose cohort.

Secondary outcomes

Cytokine profiling

In addition to the primary outcome of safety, the cytokine profile of infants following the hAEC infusion will be described. Serum samples will be collected by venepuncture pre, 24 hours and 5 days post each infusion. The cytokines of interest are interleukin (IL)—IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17, IL-18, IL-1β; interferon (IFN)—IFNγ; tumour necrosis factor (TNF)—TNFα, TNFβ; vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES); brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)—MMP9; macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)—MIP-1α; granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)—IGF-1.

Cytokine profiles differ between infants with BPD compared with those without BPD.35 Profiling of 1062 extremely low birth weight infants showed higher concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IFNγ and lower concentrations of IL-17, RANTES and TNFβ were associated with higher risk of BPD and/or death.35 Additionally, the pattern of cytokines, particularly IL-6, IL-10, IL-18, MIP-1α, BDNF, CRP, RANTES, VEGF, GM-CSF and MMP9 differ with various patterns of lung disease in preterm infants.36 37

In pre-clinical models of lung injury, the ability of hAECs to modify the inflammatory response is reflected in altered cytokine levels. In preterm sheep models, treatment with hAECs decreased levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα observed in response to inflammation induced lung injury.26 While in murine models, hAECs significantly decreased levels of IL-1β, TNFα, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, leukaemia inhibitory factor and MIP-2 following lipopolysaccharide and hyperoxia induced injury.24

Our cytokine analysis is exploratory with the aim of contributing to our understanding of the mechanism of action in vivo of hAECs and the inflammatory basis of BPD.

Clinical outcomes

The incidence and severity of BPD in the study cohort will be described using the NICHD BPD definition33 and the modified Walsh air reduction test, an assessment of the need for supplemental oxygen, at 36 weeks PMA.38 Other parameters related to respiratory outcomes will be reported including a description of the respiratory support requirements for the 2 weeks following the intervention, the use of postnatal corticosteroids, duration of respiratory support and oxygen therapy, and the incidence of pulmonary hypertension as evidenced on echocardiogram at 36 weeks PMA. Other (non-respiratory) neonatal outcomes will be reported: death; necrotising enterocolitis (modified Bell stage ≥2 and required treatment); medical or surgical treatment for patent ductus arteriosus; grade III or IV intraventricular haemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia; retinopathy of prematurity ≥stage 2; late onset culture proven sepsis; duration of hospital stay; anthropometry at discharge.

Public and Patient involvement

While the public and patients were not directly involved in the development of this study protocol the exploration of hAEC therapy for perinatal conditions was fuelled in part by a survey of pregnant women’s attitudes to and acceptance of cell therapy.39 Of the pregnant women surveyed, 80% were willing to donate their stem cells to a storage bank for others to use and 98% were accepting of stem cell therapy for their baby with the caveat that treatment was restricted to severe medical conditions.39

Statistical analysis

As this is a phase I trial, detailed statistical analysis will not be needed, but descriptive and inferential statistical analysis will be conducted as appropriate.

Ethics and dissemination

Written consent for participation in this study will be obtained from parents/guardians. Participation is voluntary and withdrawal is possible at any stage. Should withdrawal occur after an infant receives the intervention, safety monitoring will be offered in line with the monitoring outlined in this protocol.

The outcomes of this study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and presented at scientific conferences. A summary report will be made available to all participant families.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study. EKB drafted the manuscript. EMW, PGD, SEJ, RL, AM and SBH made critical revisions to and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study will be funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant #1113902.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Doyle LW, Carse E, Adams AM, et al. . Ventilation in extremely preterm infants and respiratory function at 8 years. N Engl J Med 2017;377:329–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1700827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doyle LW, Adams AM, Robertson C, et al. . Increasing airway obstruction from 8 to 18 years in extremely preterm/low-birthweight survivors born in the surfactant era. Thorax 2017;72:712–9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong PM, Lees AN, Louw J, et al. . Emphysema in young adult survivors of moderate-to-severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur Respir J 2008;32:321–8. 10.1183/09031936.00127107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boucherat O, Morissette MC, Provencher S, et al. . Bridging lung development with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. relevance of developmental pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pathogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:362–75. 10.1164/rccm.201508-1518PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stocks J, Hislop A, Sonnappa S. Early lung development: lifelong effect on respiratory health and disease. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:728–42. 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70118-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Postma DS, Bush A, van den Berge M. Risk factors and early origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lancet 2015;385:899–909. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60446-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Long-term outcomes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;14:391–5. 10.1016/j.siny.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis PG, et al. . Prediction of late death or disability at age 5 years using a count of 3 neonatal morbidities in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 2015;167:982–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Northway WH, Rosan RC, Porter DY. Pulmonary disease following respirator therapy of hyaline-membrane disease. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1967;276:357–68. 10.1056/NEJM196702162760701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Voynow JA. “New” bronchopulmonary dysplasia and chronic lung disease. Paediatr Respir Rev 2017;24:17–18. 10.1016/j.prrv.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vosdoganes P, Lim R, Moss TJ, et al. . Cell therapy: a novel treatment approach for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 2012;130:727–37. 10.1542/peds.2011-2576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lalu MM, McIntyre L, Pugliese C, et al. . Safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. PLoS One 2012;7:e47559 10.1371/journal.pone.0047559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ilancheran S, Michalska A, Peh G, et al. . Stem cells derived from human fetal membranes display multilineage differentiation potential. Biol Reprod 2007;77:577–88. 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bilic G, Zeisberger SM, Mallik AS, et al. . Comparative characterization of cultured human term amnion epithelial and mesenchymal stromal cells for application in cell therapy. Cell Transplant 2008;17:955–68. 10.3727/096368908786576507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu D, Wallace EM, Lim R. Cell-based therapies for the preterm infant. Cytotherapy 2014;16:1614–28. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kesting MR, Wolff KD, Hohlweg-Majert B, et al. . The role of allogenic amniotic membrane in burn treatment. J Burn Care Res 2008;29:907–16. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818b9e40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moodley Y, Ilancheran S, Samuel C, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cell transplantation abrogates lung fibrosis and augments repair. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:643–51. 10.1164/rccm.201001-0014OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murphy S, Lim R, Dickinson H, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cells prevent bleomycin-induced lung injury and preserve lung function. Cell Transplant 2011;20:909–24. 10.3727/096368910X543385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vosdoganes P, Wallace EM, Chan ST, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cells repair established lung injury. Cell Transplant 2013;22:1337–49. 10.3727/096368912X657657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murphy SV, Shiyun SC, Tan JL, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cells do not abrogate pulmonary fibrosis in mice with impaired macrophage function. Cell Transplant 2012;21:1477–92. 10.3727/096368911X601028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tan JL, Chan ST, Wallace EM, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cells mediate lung repair by directly modulating macrophage recruitment and polarization. Cell Transplant 2014;23:319–28. 10.3727/096368912X661409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tan JL, Chan ST, Lo CY, et al. . Amnion cell-mediated immune modulation following bleomycin challenge: controlling the regulatory T cell response. Stem Cell Res Ther 2015;6:8 10.1186/scrt542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tan JL, Tan YZ, Muljadi R, et al. . Amnion epithelial cells promote lung repair via Lipoxin A4. Stem Cells Transl Med 2017;6:1085–95. 10.5966/sctm.2016-0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu D, Tan J, Maleken AS, et al. . Human amnion cells reverse acute and chronic pulmonary damage in experimental neonatal lung injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8:257 10.1186/s13287-017-0689-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hodges RJ, Jenkin G, Hooper SB, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cells reduce ventilation-induced preterm lung injury in fetal sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:448.e8–15. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vosdoganes P, Hodges RJ, Lim R, et al. . Human amnion epithelial cells as a treatment for inflammation-induced fetal lung injury in sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:156.e26–33. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lim R, Malhotra A, Tan J, et al. . First-in-human administration of allogeneic amnion cells in premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a safety study. Stem Cells Transl Med 2018;7:628–35. 10.1002/sctm.18-0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cotten CM, Murtha AP, Goldberg RN, et al. . Feasibility of autologous cord blood cells for infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr 2014;164:973–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun J, Mikati M, Troy JD, et al. . Adequately dosed autologous cord blood infusion is associated with motor improvement in children with cerebral palsy. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2016;22:S61–S2. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.11.354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dawson G, Sun JM, Davlantis KS, et al. . Autologous cord blood infusions are safe and feasible in young children with autism spectrum disorder: results of a single-center phase i open-label trial. Stem Cells Transl Med 2017;6:1332–9. 10.1002/sctm.16-0474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang YS, Ahn SY, Yoo HS, et al. . Mesenchymal stem cells for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: phase 1 dose-escalation clinical trial. J Pediatr 2014;164:966–72. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilson JG, Liu KD, Zhuo H, et al. . Mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells for treatment of ARDS: a phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:24–32. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70291-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. JOBE AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1723–9. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murphy S, Rosli S, Acharya R, et al. . Amnion epithelial cell isolation and characterization for clinical use. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol 2010;13:1E.6.1–25. 10.1002/9780470151808.sc01e06s13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, D’Angio CT, et al. . Cytokines associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or death in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2009;123:1132–41. 10.1542/peds.2008-0526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. D’Angio CT, Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, et al. . Blood cytokine profiles associated with distinct patterns of bronchopulmonary dysplasia among extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 2016;174:45–51. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laughon M, Bose C, Allred EN, et al. . Patterns of blood protein concentrations of ELGANs classified by three patterns of respiratory disease in the first 2 postnatal weeks. Pediatr Res 2011;70:292–6. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182274f35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walsh MC, Yao Q, Gettner P, et al. . Impact of a physiologic definition on bronchopulmonary dysplasia rates. Pediatrics 2004;114:1305–11. 10.1542/peds.2004-0204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hodges RJ, Bardien N, Wallace E. Acceptability of stem cell therapy by pregnant women. Birth 2012;39:91–7. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2012.00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.