Abstract

Background and aims

Little is known about the relationship between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and body image. The aim of this systematic review was to summarise the evidence on body image dissatisfaction in patients with IBD across four areas: (1) body image tools, (2) prevalence, (3) factors associated with body image dissatisfaction in IBD and (4) association between IBD and quality of life.

Methods

Two reviewers screened, selected, quality assessed and extracted data from studies in duplicate. EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Cochrane CENTRAL were searched to April 2018. Study design–specific critical appraisal tools were used to assess risk of bias. Narrative analysis was undertaken due to heterogeneity.

Results

Fifty-seven studies using a body image tool were included; 31 for prevalence and 16 and 8 for associated factors and association with quality of life, respectively. Studies reported mainly mean or median scores. Evidence suggested female gender, age, fatigue, disease activity and steroid use were associated with increased body image dissatisfaction, which was also associated with decreased quality of life.

Conclusion

This is the first systematic review on body image in patients with IBD. The evidence suggests that body image dissatisfaction can negatively impact patients, and certain factors are associated with increased body image dissatisfaction. Greater body image dissatisfaction was also associated with poorer quality of life. However, the methodological and reporting quality of studies was in some cases poor with considerable heterogeneity. Future IBD research should incorporate measurement of body image dissatisfaction using validated tools.

Keywords: systematic review, inflammatory bowel disease, body image, quality of life

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with a range of debilitating symptoms1 and affects around 300 000 people in the UK2, over 1 million in the USA and 2.5 million across Europe.3 A potentially overlooked issue for patients with IBD is body image dissatisfaction (BID). Body image (BI) is how an individual perceives themselves physically4 and sufferers have a distorted and negative view of themselves, feeling anxious and uncomfortable about their body. Additionally, negative BI can have a serious impact on health and well-being.5

Social media and celebrity attention contribute to pressure to adhere to an ‘ideal’ body and an obsession with appearance.6 7 Discontentment with aspects such as body weight, shape, appearance and skin may contribute towards an individual having BID.8 Studies have shown patients with negative BI are more likely to suffer with depression, anxiety and feel suicidal and BID can impact negatively on relationships9 and quality of life (QoL).10.

Various tools have been used in healthcare to measure BI including the Body Image Ideals Questionnaire, the Body Image Scale and the Cash Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire (BIDQ).11 There are also condition-specific BI tools such as the Body Image Scale (BIS) for IBD.12

Both condition-specific symptoms and treatments may contribute to BID in patients with IBD, particularly during periods of active disease rather than remission. Symptoms can include urgent bowel movements, bloating, excess wind, fatigue, skin problems and ulcers. Treatment with steroids can be associated with weight gain, acne and mood swings.13 Surgeries may also impact on BI due to scarring and implementation of a stoma.14 15 Those suffering with IBD or BID are at an increased risk of mental health issues16 17; this could be worse for patients living with both conditions. Furthermore, most patients with IBD are diagnosed at adolescence,18 when BI is important. BI is currently not routinely considered in the management of IBD.

No existing or ongoing systematic reviews on BI in IBD have been identified. However, multiple primary studies, mainly cross-sectional in nature, assess BI as an outcome in patients with IBD, with disparate results. A systematic review is therefore warranted to synthesise and clarify the evidence base.

The following four questions will be addressed:

What tools are used to measure BI in patients with IBD and what are their components?

What is the prevalence and severity of BID in patients with IBD?

What factors are associated with BID in patients with IBD?

Is there an association BID in patients with IBD and QoL?

Methods

This systematic review has been reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.19 A protocol was previously registered (PROSPERO (CRD42018060999)) and submitted for publication and is currently in process.20 A summary of the methods is reported below. Selection, data extraction and quality assessment were carried out by two independent reviewers with disagreements resolved through discussion or third reviewer.

Search strategy

Bibliographic databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Cochrane CENTRAL) were searched to April 2018 using combinations of index and text terms for IBD and BI (see online supplementary table 1 for MEDLINE strategy). Strategies were adapted for each database and run without date or language restrictions. Trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, EU Clinical Trial Register) were searched for ongoing trials and reference lists of included studies were checked.

bmjgast-2018-000255supp001.docx (17.3KB, docx)

Screening and selection criteria

Study eligibility was based on the following criteria:

Study design

Any primary study reporting quantitative data.

Population

Patients of any age diagnosed with IBD. At least 50% of population must have IBD unless results are reported separately for subgroups of individuals with IBD.

Tools

Any tool measuring any aspect of BI (including QoL tools that had at least one BI-related domain or question).

Studies were also eligible (for questions 2–4) where they reported any measure of prevalence/frequency and severity of BID in patients with IBD; data on associations between any factor in patients with IBD and BID; or any association between BI and QoL measures in patients with IBD, including associations between two separate domain measures of the same tool.

Exclusion criteria

Case reports, qualitative research and conference abstracts published 3 years before the date of the searches.

Reasons for exclusion were recorded.

Data extraction

A piloted data extraction form was used. Examples of the type of data extracted are shown below.

Study characteristics

Study design, aim and setting, inclusion/exclusion criteria, recruitment methods, follow-up period.

Participant characteristics

Number of patients, age, gender, type of IBD, disease severity and activity, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, therapy/surgery.

Data for synthesis/analysis

BI measurement tool, components of tools/scales, data on BID (eg, BI scores, prevalence, thresholds for determining BID), factors associated with BI dissatisfaction and strength of association, QoL measures, strength of association between BID and QoL.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was based on critical appraisal checklists for both prevalence and cross-sectional analytical studies from the Joanna Briggs Institute.21 Studies solely included for question 1 were not quality assessed as the objective of this question was to compile a list of BI tools.

Important quality items included sample selection, response rate during enrolment in the study, clear inclusion criteria and measurement of outcomes in a valid and reliable way.

Analysis

A narrative synthesis was carried out separately for each question, with key findings tabulated. Substantial heterogeneity relating to populations, tools and settings was apparent in the included studies meaning that meta-analysis was not appropriate. Consistencies and discrepancies in findings between studies were noted and discussed in the context of any likely sources of heterogeneity. Quality assessment findings were used when considering the strength of evidence for the latter three questions.

Results

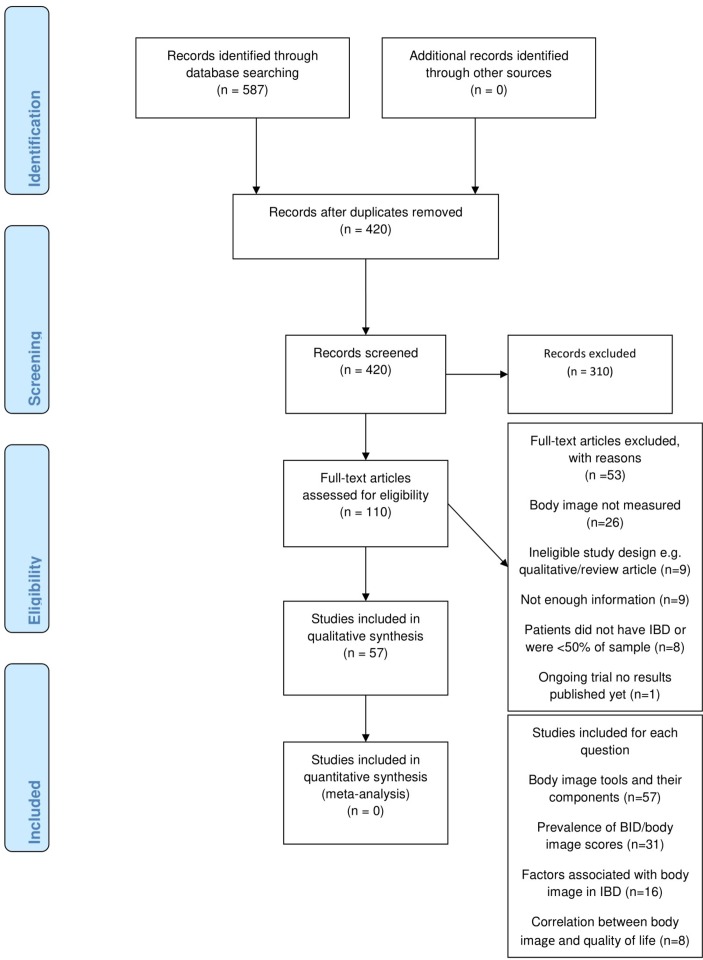

Database searches identified 587 records and 5712 14 22–76 studies were included, with some studies eligible for multiple questions (see figure 1 for selection process and reasons for exclusion). All 57 papers reported using BI tools, 3114 22–26 30 31 33–39 42 47 50 51 53 54 58 60–65 67 69 71 72 reported prevalence or mean/median BI scores, 1614 23 24 30 34–36 47 54 58 60 61 63 65 67 71 studies presented factors associated with BID and 814 22–24 34 61 65 71 studies reported correlations between QoL and BI.

Figure 1.

Selection process of records for inclusion/exclusion detailed in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart. BID, body image dissatisfaction; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Question 1: what tools are used to measure BI and what are their components?

Of the 57 studies measuring BI, 51 were cross-sectional while the others varied (case–control,25 prospective cohort,51 65 case series,39 randomised controlled trial64 and non-randomised intervention study42). Study populations included adults and children in settings including outpatients, presurgery/postsurgery, summer camps and online registries, from countries across the world. Twenty studies focused on BI as one of the main outcomes, but only six of these studies were non-surgery based.

Fifteen tools were identified (table 1). Seven tools were specifically for BI and eight were QoL tools which included a BI domain or question(s). The most frequently applied tool specific to BI was the Body Image Questionnaire (BIQ) which was used in 14 studies. The BIS was used in five studies and is the only tool validated in an IBD population. IMPACT-III (or earlier IMPACT-II) is a validated QoL questionnaire aimed at adolescents and children with IBD and includes a BI domain. It was used across 18 studies. The remaining 12 tools were used in only one to three studies, respectively.

Table 1.

Tools identified and used across included studies

| Measurement tool | Type of tool | Intended target population | Is tool validated? | Scoring | Number of studies tool used in |

| Body image tools | |||||

| ASWAP | Body image | Initially used in patients with scleroderma | Yes but not in patients with IBD | 15 items rated on 7-point scale. Questions corresponding to items 4–11 were reverse scored such that higher scores reflect greater dissatisfaction | 1 |

| Askevold’s Body Image Test | Body image | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 2 |

| Body Image and Self-Consciousness During Intimacy Scale |

Body image and sexual self-consciousness | Women | No | 0–75, higher scores poorer body image | 1 |

| BIA/BIA-P | Body image | Adults, no specific clinical population | Unclear | Based on body image silhouettes ranging in size. Score=difference between current body size and ideal body size | 1 |

| BIQ | Body image | Originally caesarean or appendectomy patients, now patients with IBD | No | 5–20, higher score better body image | 14 |

| BIS | Body image | Patients with cancer | Yes | 0–30, lower score better body image | 5 |

| Cash Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire | Body image | Range of clinical groups | Yes but not in patients with IBD | 7–35, higher score poorer body image | 2 |

| QoL tools with a body image component | |||||

| DUX-25 | Quality of daily functioning (1 of 4 domains relate to body image) | School-age children | No | Higher scores, better QoL | 1 |

| EORTC-QLQ-CR38 | QoL questionnaire (3 of 38 items relate to body image) | Patients with cancer | Yes but not in patients with IBD | 38 items with four category responses. Functional scales: higher score higher functioning. Symptoms scales: higher score higher level of symptoms | 1 |

| EORTC-QLQ-CR29 | QoL questionnaire (3 of 29 items relate to body image) | Patients with cancer | Yes but not in patients with IBD | 29 items with four category responses Functional scales: higher score higher functioning Symptoms scales: higher score higher level of symptoms |

1 |

| IMPACT-III or IMPACT II | Health-related QoL (3 of 35 items relate to body image) | Children and adolescents with IBD | Yes | 35–175, higher scores better QoL | 18 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease Stress Index | Assessing the extent to which IBD has caused alterations in lifestyle (1 of 10 items relate to body image) | Patients with IBD | Unclear | Eight scales with a score of 0–3 (no impact–a great deal of impact) | 1 |

| RFIPC | QoL questionnaire (1 item of 25 relate to body image) | Patients with IBD | Yes | 0–100, higher score poorer QoL | 3 |

| Stoma Quality of Life Scale | Stoma-related (5 items of 19 relate to body image and sexuality) | Patients with stoma | Yes (in ostomy patients) | Five scales, 19 questions. Each scored 1–5 (never–always). Average scores for each scale calculated | 3 |

| The Karolinska Psychodynamic Profile | Assessment of stable modes of mental functioning and character traits (1 subscale and 3 of 18 items relate to body image) | No specific clinical population | Yes | Each subscale is graded from 1 to 3 (most normal–least normal) | 2 |

ASWAP, Adapted Satisfaction with Appearance scale; BI/BIA-P, Body Image Assessment/Body Image Assessment Preadolescent; BIQ, Body Image Questionnaire; BIS, Body Image Scale; DUX-25, Dutch Children’s AZL/TNO Quality of Life Questionnaire; EORT-QLQ-CR38/EORT-QLQ-CR29, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life questionnaire for Colorectal Cancer; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IMPACT-II/IMPACT-III, a measure of health-related quality of life in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease; QoL, quality of life; RFIPC, Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns.

None of the tools included had a clear cut-off point for defining BID but offered an indication of increasing or decreasing likelihood of dissatisfaction. In some tools, a higher score indicated better BI (BIQ, EORTC, DUX-25). In others, a higher score indicated increased BID (IMPACT, BIS, RFIPC, IBDSI (Inflammatory bowel disease stress index), Body Image Self-Consciousness during Intimacy Scale, BIDQ and ASWAP).

Tools where items had similar themes were grouped to show general focus of BI questions and are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Body image tools with similar questions grouped into overarching themes

| Body image tool | Components | ||||||||

| Satisfaction with appearance | Attractiveness | Socialising /work |

Avoidance of people or tasks | Feeling feminine/ masculine | Effect of disease on body | Scar satisfaction | Satisfaction with body both naked and dressed | Distressing thoughts | |

| BIS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| BIQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| CBIDQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| ASWAP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

Similar components of tools were grouped into themes shown above. Askevold’s Body Image Test (no information in paper or online), Body Image and Self-consciousness during Intimacy Scale (too specific) and the Body Image Assessment (based on figural drawing scales) were not included.

ASWAP, Adapted Satisfaction with Appearance Scale; BIQ, Body Image Questionnaire; BIS, Body Image Scale; CBIDQ, Cash Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire.

What is the prevalence of BI dissatisfaction in patients with IBD?

Thirty-one studies including a total of 3634 patients reported on prevalence or severity of BID (see table 3 for study characteristics). Seventeen studies14 22 23 25 30 31 38 42 53 54 58 60 61 65 69 71 72 included both patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Ages ranged from 2 to 71, and 18 studies22 30 38 40–42 51–53 57 59–62 69 70 72 75 included only children/adolescents. Fourteen studies24–26 33–37 39 47 50 63 64 67 included surgery patients and one study included only women.71

Table 3.

Study characteristics of papers included for questions 2, 3 and 4

| Study | Design | Population | Country | Patients (n) | Number of UC/CD/other | Body image tool | Outcomes | Body image prevalence/score |

| Beld et al (2010)24 | Cross-sectional | UC or FAP undergone restorative proctocolectomy IPAA Jan 1992 to Oct 2008 | Netherlands | 26 | UC (16) FAP (10) | BIQ | Mean body image scores (SD) | Men 16.3 (3.1) Women 13.5 (4.1) |

| Brown et al (2015)26 | Cross-sectional | Patients with UC who had colectomy within the past 10 years, data collected from Nov 2010 to Jul 2011 | Canada, Australia, UK | 351 | All UC | BIQ | Median body image scores (IQR) Prevalence of ‘quite a bit’ or ‘extreme’ negative impacts on body image as a result of colectomy |

Men 8 (IQR 6–11) Women 11 (IQR 8–14) Age group >50 years 8 (IQR 6–11) Age group <50 years 10 (IQR 7–13) 21%–34% reported negative impacts on body image |

| Dunker et al (1998)34 | Cross-sectional | Patients with CD undergoing open or laparoscopic resection at Leiden University Medical Centre | Netherlands | 34 | All CD | BIQ | Mean body image scores | Open 16.4 (10–20) Laparoscopic 18 (13-20) (SD not reported) |

| Dunker et al (2001)33 | Cross-sectional matched comparison | Patients with UC who underwent laparoscopic-assisted IPAA and matched patients with conventional IPAA | Netherlands | 32 | UC (28) FAP (4) | BIQ | Mean body image scores (SD) | Laparoscopic 19 (1.3) Conventional 17.9 (SD not reported) |

| Eshuis et al (2008)35 | Repeated cross-sectional | Patients who underwent ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease from 1995 until 1998 two centres | Netherlands | 71 (medical file analysis) 61 (returned questionnaires) |

All CD | BIQ | Mean body image scores (range) | Open 15.63 (6–20) Laparoscopic 16.3 (7–20) (SD not reported) |

| Eshuis et al (2010) | Repeated cross-sectional | Patients with CD who had ileocolic resections between Sep 1999 and Nov 2003 | Netherlands | 55 | All CD | BIQ | Median body image scores (IQR) | Open 18.0 (IQR 16–19) Laparoscopic 19.0 (IQR 17–20) |

| Giudici et al (2017)39 | Case series (abstract only) | Dec 2014–Dec 2015 Consecutive patients undergoing laparoscopic proctectomy for UC | Italy | 10 | All UC | Self-designed body image questionnaire | Mean body image score | 59 (SD not reported) |

| Kjaer et al (2014) | Cross-sectional | Adult patients treated with laparoscopy-assisted or open IPAA at Odense University Hospital during the period between Oct 2008 and Mar 2012 | Denmark | 50 | UC (44) FAP (4) Other (2) | BIQ | Median body image scores (range) | Laparoscopic 8 (5–18) Open 9.5 (5–20) |

| Polle et al (2007)63 | Repeated cross-sectional | Patients eligible for an elective proctocolectomy with IPAA for UC or FAP were included in a randomised trial | Netherlands | 53 | UC (34) FAP (19) | BIQ | Mean body image scores (limited data) | Women open group 15 Laparoscopic group 18 (SD not reported) |

| Ponsioen et al (2017)64 | Randomised controlled trial | Eligible patients aged 18–80 years, had active Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum and had not responded to at least 3 months of conventional therapy with glucocorticosteroids, thiopurines or methotrexate. Patients with diseased terminal ileum longer than 40 cm or abdominal abscesses were excluded | Netherlands and UK | 70 Infliximab group 73 Laparoscopic ileocaecal resection |

All CD | BIQ | Mean body image scores (only given for resection group) | Resection group: Baseline 16 Endpoint 17.8 (SD not reported) |

| Scarpa et al (2009)67 | Prospective case series | Patients admitted for intestinal surgery for CD May 2006–July 2008 | Italy | 47 | All CD | BIQ | Median body image score (IQR) | 5 (5–8) |

| Eshuis et al (2010)37 | Prospective case series | A consecutive series of patients who had an indication for a laparoscopic ileocolic resection were invited to participate. Patients with CD | Netherlands | 10 | All CD | BIQ | Median body image scores | Before surgery 17.0 After surgery 19.0 |

| Bengtsson et al (2011)25 | Case–control | Patients with preoperative diagnosis of UC or CD who underwent IPAA | Sweden | 101 (72 controls, 29 study group) |

Controls; UC (60) CD (0) Study group; UC (25) CD (4) |

BIS | Median body image scores. | Study group: Men 6.5 Women 10 Control group: Men 1 Women 3 |

| Trindade et al (2017)71 | Cross-sectional | Female participants with ages between 18 and 40 years who had not undergone IBD-related surgery | Portugal | 96 | UC (58) CD (38) | BIS | Mean body image score (SD) | 10.10 (7.73) (SD not reported) |

| Vlahou et al (2008)72 | Cross-sectional | Adolescents with IBD who attended clinics at two separate hospitals and a camp for children with IBD | USA | 44 | Breakdown not reported | BSQ (modified version of BIQ) and BIA-P | Mean body image scores (SD) | BSQ: Men 36.45 (4.88) Women 33.52 (7.77) BIA-P: Men 0.41 (0.85) Women 0.77 (0.92) |

| Grootenhuis (2009)42 | Non-randomised controlled study | Adolescents with IBD who were under medical care at Emma Children’s Hospital AMC and members of Crohn’s and Colitis Association Netherlands | Netherlands | 18 controls; 22 intervention | Controls CD (11) UC (4) IBDU (3) Intervention CD (17) UC (5) IBDU (0) | DUX-25 | Mean body image domain scores (SD) | Intervention: baseline 55.4 (18.6) post intervention 68.9 (17.7) Control: baseline 60.0 (17.4) post intervention 59.0 (20.1) |

| Bel et al (2015)23 | Cross-sectional with controls | 18–70 UC or CD | Netherlands | 287 (197 healthy controls) |

UC (132) CD (155) | EORTC-QLQ-CR38 | Mean body image domain scores (SD) | Active: Men 5.61 (2.31) Women 6.2 (2.78) Remission: Men 3.82 (1.33) Women 4.58 (1.68) |

| Shepanksi (2009) | Before and after study | Children attending Camp Guts and Glory in Pennsylvania | USA | 61 | CD:UC (2:1) | IMPACT II | Mean body image domain scores (SD, for before and after camp) | By age: Age 9–10: Pre 14.6 (4.1) Post 16.4 (3.7) Age 11–12: Pre 11.4 (4.9) Post 13.2 (5.0) Age 13–14: Pre 12.9 (5.2) Post 13.8 (5.9) Age 15–16: Pre 12.3 (5.0) Post 11.2 (5.4) |

| Abdovic et al (2013)22 | Cross sectional validation study | Children aged 9 years or older with confirmed diagnosis of IBD for more than 6 months from inpatient and outpatient clinics at particular centres. | Croatia | 104 | UC (30) CD (74) | IMPACT III | Mean body image domain score (SD). | 12.03 (1.96) |

| Chouliaras et al (2017)30 | Cross-sectional | Patients with UC and CD hospitalised or followed in outpatient clinic in Athens | Greece | 99 | UC (37) CD (62) | IMPACT III | Mean body image domain scores (SD) | Overall 71.5 (17.9) UC 67.3 (22.4) CD 72.6 (19.3) No significant relationship between body image and assessed disease characteristics or prescribed medications |

| Gallo et al (2014)38 | Cross-sectional | Children between the ages of 8 and 18 years, who had been diagnosed with IBD at least 6 months before, and were being followed at the Paediatric Gastroenterology Service of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina, or at the private office of one of the coauthors (MO) and one of their parents | Argentina | 27 | UC (17) CD (9) | IMPACT III | Mean body image domain score (SD) | 76.54 (16.06) |

| Lee et al (2015)51 | Prospective observational study | Children and young adults less than 22 years of age started on EN or anti-TNF therapy for active CD at Hospital for Sick Children Toronto and Children’s Hospital Philadelphia | Canada and USA | 90 | All CD | IMPACT III | Median body image domain scores (range) | Baseline PEN 71 (54–75) EEN 58 (58–75) TNf 67 (50–83) |

| Mason et al (2015)53 | Prospective observational study | Adolescents >10 years old with confirmed diagnosis of IBD attending gastroenterology clinic at Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow | Scotland | 63 | UC/IBDU (18) CD (45) | IMPACT III | Mean body image domain score | 7 (SD not reported) |

| Ogden et al (2011)60 | Cross-sectional validation study | Unclear—children with IBD | UK | 97 | UC (12) CD (64) IBDU (21) | IMPACT III | Mean body image domain score | 63.5 (95% CI 56.5 to 70.6) (SD not reported) |

| Perrin et al (2008)61 | Cross-sectional | Children aged 8–17 years diagnosed with UC or CD 6 months before the study followed at 1 of 6 paediatric gastroenterology centres. No other chronic conditions | USA | 220 | UC (59) CD (161) | IMPACT III | Mean body image domain scores (SD) | 68.1 (19.6) UC 68.6 (20.8) CD 67.9 (19.2) |

| McDermott et al (2015)14 | Cross-sectional | Patients with histologically confirmed IBD attending ambulatory clinics in 1 of 2 medical centres between Jul 2011 and Nov 2012 | Ireland | 330 | UC (145) CD (194) | Modified BIS and Cash Body Image Scale (qualitative only) | Median body image score (range) Prevalence |

6 (0–27) 13% patients reported no concerns about any aspect of body image |

| Saha et al (2015)65 | Prospective observational study | Patients with UC, CD or IBDU aged 18 and above enrolled in the Ocean State Crohn’s and Colitis Area Registry (OSCCAR) with a minimum of 2 years of follow-up | USA | 274 | CD (145) UC/IBDU (129) | ASWAP | Mean body image scores (SD) | Baseline: Women 30.1 (14.4) Men 21.2 (8.4) Year 1: Women 28.2 (14.1) Men 24.5 (12.5) Year 2: Women 28.8 (13.2) Men 24.1 (13.5) |

| Muller et al (2010)58 | Cross-sectional | Patients with IBD aged 18–50 from a database of patients with IBD maintained by the Southern Adelaide IBD Service | Australia | 217 | UC (85) CD (127) IBDU (5) | No specific tool—range of questions regarding body image and impact of IBD on this | Prevalence (%) of body image dissatisfaction | 66.8% of patients reported impaired body image |

| de Rooy et al (2001)31 | Cross-sectional | Outpatients of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Centre, Mount Sinai Hospital. Subjects were a convenience sample waiting for a regularly scheduled physician appointment | USA | 241 | UC (121) CD (120) | RFIPC | ‘Feelings about body’ question mean score (SD) | 42.84 (33.97) |

| Maunder et al (1999)54 | Retrospective analysis | Patients with IBD who had completed the RFIPC and a survey of demographic and disease-related variables in one of three previous studies | Unclear | 343 | UC (186) CD (157) | RFIPC | ‘Feelings about body’ question mean scores | Women 52.13 (34.8) Men 38.16 (33.83) |

| Kuruvilla et al (2012)50 | Cross-sectional (abstract only) | Consecutive patients who had undergone IPAA or a permanent ileostomy for UC by a single surgeon, presenting for their annual follow-up visit from Jul through Sep 2011, were offered participation in the study. A randomly chosen group of subjects who did not have scheduled appointments during the study period were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the study | USA | 59 | All UC. IPAA (35); TPC (24) | Stoma Quality of Life Scale | Mean (SD) and median (range) body image/sexuality domain scores | IPAA: Mean 93.1 (9.7) Median 100 (65–100) TPC: Mean 76.4 (14.6) Median 80 (50–100) |

ASWAP, Adapted Satisfaction with Appearance scale; BI/BIA-P, Body Image Assessment/Body Image Assessment-Preadolescent; BIQ, Body Image Questionnaire; BIS, Body Image Scale; BSQ, Body Satisfaction Questionnaire; CD, Crohn’s disease; DUX-25, Dutch Children’s AZL/TNO Quality of Life Questionnaire; EEN, Exclusive Enteral Nutrition; EORT-QLQ-CR38/EORT-QLQ-CR29, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life questionnaire for Colorectal Cancer; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBDU, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; IMPACT-II/IMPACT-III, a measure of health-related quality of life in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; PEN, partial enteral nutrition; RFIPC, Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TPC, total proctocolectomy; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Only three studies reported prevalence. Brown et al 26 found that 21%–34% of patients with UC reported negative impacts on BI using BIQ. McDermott et al 14 found that 87% of patients reported some form of concern about an aspect of their BI using the Cash Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire. Muller et al 58 reported that 66.8% of patients with IBD stated they had impaired BI based on a researcher-devised questionnaire. The other 28 studies reported mean/median BI scores based on a range of tools.

In studies with populations undergoing surgery, it was found that there was no significant difference in BI scores (using the BIQ) after laparoscopic or open/conventional surgery in patients with IBD.33–35 63 77 Only one study found BI scores to be significantly improved after laparoscopic surgery compared with conventional surgery in CD.36.

BI was included as an outcome across 31 studies. All but one study compared results within the included IBD population, for example, UC versus CD, surgery versus no surgery and men versus women. Bel et al 23 found that women with IBD with disease in remission scored comparably with women in a healthy population. One longitudinal study by Saha et al 65 measured scores over 2 years and found that BI did not change despite improvements in symptoms.

What factors are associated with BID in patients with IBD?

Sixteen studies14 23 24 30 34–36 47 54 58 60 61 63 65 67 71 totalling 2333 patients with IBD reported the association between various factors and BID (see table 4). Factors included those related to demographics as well as disease and treatment-related characteristics. Ten studies14 24 34–36 47 63 65 67 71 used a specific BI tool and six34–36 47 63 67 focused on comparative surgery techniques. Three studies30 60 61 included a paediatric population; the remaining studies included adults. BI was one of the main outcomes in most of these studies and the study by Saha et al 65 was the first longitudinal follow-up of BID in IBD according to the authors.

Table 4.

Most common factors found to be significantly associated with impaired body image in IBD as reported in each study, including associations between reduced body image and reduced QoL

| Factor | Study | ||||||||||||||||

| Abdovic 201322 | Bel 201523 | Beld 201024 | Chouliaras 201730 | Dunker 199834 | Eshuis 200835 | Eshuis 2010 |

Kjaer 2014 | Maunder 199954 | McDermott 201514 | Muller 201058 | Ogden 201160 | Perrin 200861 | Polle 200763 | Saha 201565 | Scarpa 200967 | Trin dade 201771 |

|

| Female gender | r=−0.18* | Diffe rence in means p=0.08 |

Diffe rence in means p>0.10 |

Diffe rence in scores p=0.18 |

No signif icant asso ciation |

Fem ales signif icantly worse scores* |

p<0.001* | Diffe rence in propo rtions p=0.0007 |

Signif icantly worse scores in open surgery group p=0.004* |

p<0.0001* | |||||||

| Higher disease/ symptom activity |

r=0.38* | No significant association | r=0.5* | p<0.001* | p=0.50 | p=0.003* | In UC p=0.006* In CD p=0.003* |

Multiple regression β=0.426 p=0.006* | Active disease r=0.18 Symptoms r=0.40* |

||||||||

| Fatigue | r=0.55* | ||||||||||||||||

| Disease subtype | No significant association | p=0.63 | Difference in proportions p=0.094 | p=0.05 | No association found | ||||||||||||

| Age | r=−0.18* | No sign ificant asso ciation |

Younger age p<0.001* | r=−0.06 | |||||||||||||

| Steroids | No signif icant asso ciation |

No signif icant associ ation |

p=0.03* | p=0.05* | p=0.02* | r=0.22* | |||||||||||

| Smoking | p=0.001* | ||||||||||||||||

| Open/ conventional surgery |

Difference in scores p=0.2 | Difference in means p=0.51 | Difference in median p=0.03* | Difference in median p=0.17 | No significant differences | Multiple regression (for laparoscopic approach) β=0.331 p=0.036* | |||||||||||

| Increased BMI | Women only p<0.001* | No significant association | r=0.25* | ||||||||||||||

| Impaired QoL | r=0.52* | r=0.67* | r<0.41 | r=0.5* | p<0.001* | r=0.51* | One-unit increase ASWAP score associated with a 0.62 decrease in BDQ (p<0.0001)* | Psychological QoL r=0.56* Physical QoL r=0.50* |

|||||||||

With some tools, higher scores indicate better body image/QoL and in others higher scores indicate worse body image/QoL. This may result in both positive and negative correlation coefficients. Where applicable, signs have been flipped for ease of interpretation to clearly show the positive correlation between body image and quality of life.

*Significant association found.

ASWAP, Adapted Satisfaction with Appearance Scale; BIDQ, Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire; BMI, body mass index; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; QoL, quality of life.

In 6/10 studies,14 23 54 58 63 65 female gender was found to be significantly associated with increased BID. One study58 reported the odds of BID was over three times more in women than men (p=0.001), with strong associations reported in the other five studies. Increased disease activity was found to have a significant but moderate positive association in 7/9 studies.14 23 34 61 65 67 71

Other factors found to be significantly associated with increased BID included steroid use,14 60 65 71 age,14 23 increased BMI,14 71 smoking14 and fatigue23 (table 4). Saha et al 65 also found a significant association between extraintestinal manifestations and increased BID, but were the only study to assess this. Laparoscopic surgery was found to be associated with improved body image in 2/6 studies.36 67 Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) seemed to result in patients being satisfied with their body image in two studies,24 26 but they lacked a comparative surgery group. One study50 compared IPAA and ileostomy and found better body image scores in the IPAA group. No significant associations were found between disease subtype and increased BID.

Is there an association between BID and quality of life in patients with IBD?

Eight studies14 22–24 34 62 65 71 explored a potential association between BID and QoL across a total of 1371 patients, with seven presenting a significant association. Three studies22 24 61 (table 4) focused on younger populations with the rest including adults only. The majority of studies included populations with both UC and CD while two 24 34 included only one subtype.

Statistically significant weak to moderately strong correlations were present in five studies22 23 34 61 71 ranging from r=0.34 to r=0.67. Furthermore, McDermott et al 14 found that when using the BI scale, there was a significant difference in scores between those with good or poor QoL. Trindade et al 71 found that BI was positively correlated with psychological and physical QoL. Saha et al 65 found that a one-unit increase in the total ASWAP score (indicating poorer body image) was associated with a 0.62 decrease in QoL score (p<0.0001).

Various QoL tools (see table 1) were used across studies with some using more than one. Four of these questionnaires used (IMPACT II and III, GIQLI (Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index) and WHOQOL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality of Life Instruments)) contain a question or domain on BI, potentially making them more likely to correlate with BI questionnaires.

Risk of bias

The 31 studies relevant for questions 2–4 were assessed using criteria from the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for analytical cross-sectional and prevalence designs (online supplementary table 2). Only cross-sectional data were relevant for the review. Poor reporting of quality criteria in many studies made quality assessment difficult. Where criteria were reported, the overall quality was variable. Most studies had some areas of low and higher quality. Only one study, McDermott et al,14 was able to demonstrate adequate response rates, validated outcome measurement tools and adjustment for confounders. However, Chouliaras e t al,30 Trindade e t al,71 Lee e t al 51 and Bel e t al 23 adjusted for confounders and used validated outcome measurement tools but lacked adequate response rates.

bmjgast-2018-000255supp002.docx (26.7KB, docx)

Twenty studies (64.5%) used an appropriate sample frame with acquisition of patients from outpatient settings, IBD registries or healthcare records. Eighteen studies (58.1%) clearly reported inclusion criteria applied when recruiting participants. Only 12 studies (38.7%) had response rates >75%. Fifteen studies (48.4%) used a tool which had been validated using factor analysis and internal consistency analysis to measure BI. The others used non-validated tools. Twelve studies14 35 50 51 58 64 65 72 adjusted for potential confounders such as age, gender, BMI and previous surgery often using multiple regression models. Several studies reported limited demographic data. It should also be noted that sample sizes of many of the studies were small and CIs were mostly not presented.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Overall, 15 different tools were used across 57 studies to measure BI in patients with IBD. These included QoL tools incorporating BI questions or domains, BI tools and other adapted questionnaires. None offer a defining threshold for presence or absence of BID, which is not commonly considered as a specific psychological disorder unlike body dysmorphia.

It remains unclear whether patients with IBD suffer with BID more so than the general population as most studies reported mean values with no reference to healthy population values. Three studies estimated a prevalence of a negative BI based on one question, and this varied between 21% and 81%. This wide variation likely reflects the differences in tools and study characteristics. All three studies were based on self-report questionnaires with a wide age range and registry or hospital-based population.

Certain factors including female gender, disease activity and steroid use were consistently found to be significantly associated with increased BID in patients with IBD. There was also a significant association between increasing BID and decreasing QoL reported in eight studies. These findings are consistent with a previous narrative review78 assessing BID and sexual functioning in patients with IBD.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

This is the first systematic review assessing BID in an IBD population, and a robust methodology was employed to ensure that bias and errors were minimised. A sensitive search strategy means that it is unlikely that relevant studies were missed and over 50 studies have contributed to the evidence base in an area previously unexplored by a systematic review.

The review has some limitations. Some of the extracted data are based on abstracts only where full texts could not be obtained from the authors. This will have resulted in some missing information.

Furthermore, qualitative studies were not included as this was considered beyond the scope of this review. It is likely that there are qualitative studies which could offer a deeper insight into perception of BI in patients with IBD.

Strengths and weaknesses of the evidence

There are some weaknesses within the included evidence. All studies had some areas of high risk of bias or had poorly reported methodological criteria, thus hampering quality assessment. Some studies had very low response rates leading to possible under-representation of certain groups. Few studies adjusted for confounders which could have resulted in overestimates of associations.

A further issue is the lack of healthy control groups. Although it appears that patients with IBD are concerned about BI, it is difficult to determine whether they are affected more than the general population. However, it has been found that children and adolescents with chronic illnesses such as asthma, cystic fibrosis and diabetes do have increased BID compared with healthy peers.79

Non-validated tools were often used for measuring BI and the reliability and validity of findings based on these is therefore unknown. There is also still little known about potential changes in BI perception over time.

Findings in context

This review is consistent with findings from the narrative review by Jedel e t al 78 which found that BI could potentially be a problem in patients with IBD. While surgery has been found to be an important contributing factor in BID in other research,80 it is unclear how it impacts on patients with IBD. An association between BID and poorer QoL has been highlighted in both.

Females and adolescents are more likely to be concerned with BI and to suffer with BID compared with men and older people.81–86 While we found inconsistent results surrounding age, IBD is often diagnosed in adolescence when BID could be more of a concern.

In oncology, BI is more widely researched. One study suggested patients with gynaecological cancer suffered with BID which predicted emotional well-being.87 Another study with patients with advanced cancer suggested BID was associated with depression, anxiety and fatigue.88 Qualitative research in pregnancy89 and systematic lupus90 suggests BI can affect medication compliance and that patients would like more support around dealing with BI issues. This could also be true for patients with IBD.

Finally, a previous systematic review found that children with chronic conditions were more likely to be dissatisfied with their body than healthy peers.79 Although patients with IBD were not included, patients with similar chronic diseases like diabetes, cancer, asthma and scoliosis were suggesting patients with IBD could be similarly affected.

Implications

This evidence identified in this review suggests an association between BID and poorer QoL as well as finding factors influencing BI in patients with IBD. There were, however, limitations to the evidence in terms of methodological quality and/or reporting. Also, results were difficult to compare across studies. More promisingly, BI is becoming an increasingly assessed outcome, highlighting the need for continued research in this area.

Current research suggests that age, gender, medication and disease activity in IBD may impact on BI. These could be taken into account by clinicians and patients by altering therapy or targeting comorbidities which could have a beneficial effect on BID. Interventions to improve BI could be incorporated into treatment strategies, which may in turn help to improve QoL. A recent systematic review91 found that stress management, mindfulness and talking therapies may offer small to moderate improvements in BI; however, there is a lack of evidence from good randomised controlled trials.

Future research

Future research should focus on developing a consensus around which validated tool or tools are best suited to measuring BID in an IBD population. While we describe validity of tools such as the Body Image Scale, we have not independently verified this; therefore, we could not recommend a particular tool. Defining thresholds may allow estimation of the prevalence of BID in this population. Establishing reference values in a healthy population would allow for more meaningful interpretation of BID scores across different chronic diseases. Enrolling patients from diagnosis and following them over time would be useful to measure how BI changes with duration, activity of disease and treatment. While more severe IBD symptoms or invasive treatment options may exacerbate BID, BID itself and any associated anxiety or depressive symptoms may in turn exacerbate IBD symptoms,92 93 and future research should also address this association. If BID is recognised and treated early, it may contribute to preventing worsening disease course. It may also be useful to encourage the use of BI as a patient-reported outcome in future IBD studies. This would increase data on BID and lead to a greater understanding of the condition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the evidence suggests a detrimental effect of IBD on BI, but uncertainty remains due a lack of comparison data from healthy populations. Associations of BID with disease-related factors such as steroid treatment, fatigue, disease activity and surgery are apparent and findings suggest a correlation between impaired BI and poorer QoL. These results should be cautiously interpreted due to risk of bias and/or poor reporting of methodological criteria among included studies, and the wide variation between populations, BI tools and scoring systems. Future studies should make use of validated measurement tools and include BI as a main outcome where appropriate.

Footnotes

Contributors: SEB identified the topic, undertook scoping, defined the question, developed the protocol and wrote the draft of the manuscript. IMH contributed to the methods development and carried out second reviewer tasks as well as helping to draft, comment on and approve the final version of this paper. DM provided substantial methodological input to aid protocol development and assisted with drafting and reading, commenting on approving the final version. JD provided methodological input and read, commented on and edited the draft and approved the final version.

Funding: During this research, IMH was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Methods—Systematic Review Fellowship and SEB was a locally funded trainee in systematic reviews at the University of Birmingham with agreement from the NIHR.

Disclaimer: This article presents independent research funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention What is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)?, 2014. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/what-is-ibd.htm [Accessed 30 Jan 2017].

- 2. Crohn's, Colitis UK About inflammatory bowel disease, 2017. Available from: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/about-inflammatory-bowel-disease [Accessed 18 Feb 2017].

- 3. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:720–7. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Eating Disorders Association What is body image?, 2017. Available from: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/what-body-image [Accessed 17 Feb 2017].

- 5. Griffiths S, Hay P, Mitchison D, et al. Sex differences in the relationships between body dissatisfaction, quality of life and psychological distress. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016;40:518–22. 10.1111/1753-6405.12538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown Z, Tiggemann M. Attractive celebrity and peer images on instagram: effect on women's mood and body image. Body Image 2016;19:37–43. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen R, Blaszczynski A. Comparative effects of Facebook and conventional media on body image dissatisfaction. J Eat Disord 2015;3:23 10.1186/s40337-015-0061-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holland G, Tiggemann M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016;17:100–10. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dyl J, Kittler J, Phillips KA, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder and other clinically significant body image concerns in adolescent psychiatric inpatients: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2006;36:369–82. 10.1007/s10578-006-0008-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim JS, Kang S. A study on body image, sexual quality of life, depression, and quality of life in middle-aged adults. Asian Nurs Res 2015;9:96–103. 10.1016/j.anr.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cash TF, 2017. Body image assessments. Available from: http://www.body-images.com/assessments/ [Accessed 17 Feb 2017].

- 12. McDermott E, Moloney J, Rafter N, et al. The body image scale: a simple and valid tool for assessing body image dissatisfaction in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:286–90. 10.1097/01.MIB.0000438246.68476.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. NHS Choices Corticosteroids—side effects, 2015. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Corticosteroid-(drugs)/Pages/Sideeffects.aspx [Accessed 19 Feb 2017].

- 14. McDermott E, Mullen G, Moloney J, et al. Body image dissatisfaction: clinical features, and psychosocial disability in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:353–60. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zaghiyan K, Ghantiwala V, Le Q. Is body image and cosmesis better after double-port laparoscopic or open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA)? 2011;54:e119. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Michaela MB, Dianne N-S. Body dissatisfaction: an overlooked public health concern. J Public Ment Health 2014;13:64–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bernstein CN, Hitchon CA, Walld R, et al. Increased burden of psychiatric disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;152 10.1093/ibd/izy235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NHS Choices Inflammatory bowel disease, 2015. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Inflammatory-bowel-disease/Pages/Introduction.aspx [Accessed 17 Feb 2017].

- 19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beese SE, Harris IM, Moore D, et al. Body image dissatisfaction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2018;7:184 10.1186/s13643-018-0844-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The Joanna Briggs Institute Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abdovic S, Mocic Pavic A, Milosevic M, et al. The IMPACT-III (HR) questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in croatian children with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2013;7:908–15. 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. LGJ Bel, Vollebregt AM, Van der Meulen-de Jong AE. Sexual dysfunctions in men and women with inflammatory bowel disease: the influence of IBD-related clinical factors and depression on sexual function. J Sex Med 2015;12:1557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beld M, Van Balkom K, Visschers R. Long term results after restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis at young age. Colorectal Dis 2010;12:16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bengtsson J, Lindholm E, Nordgren S, et al. Sexual function after failed ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. J Crohns Colitis 2011;5:407–14. 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown C, Gibson PR, Hart A, et al. Long-term outcomes of colectomy surgery among patients with ulcerative colitis. Springerplus 2015;4:573 10.1186/s40064-015-1350-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cabras PL, Giardinelli L, la Malfa GP. Variations in body image during autogenic training in patients with psychosomatic gastrointestinal disorders. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali 1986;178:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Camilleri-Brennan J, Munro A, Steele RJ. Does an ileoanal pouch offer a better quality of life than a permanent ileostomy for patients with ulcerative colitis? J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:814–9. 10.1016/S1091-255X(03)00103-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carlsen K, Jakobsen C, Hansen LF. Quality of life in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients in a self-administered telemedicine randomised clinical study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2016;10:S421–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chouliaras G, Margoni D, Dimakou K, et al. Disease impact on the quality of life of children with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:1067–75. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i6.1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Rooy E. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a clinical population. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1816–21. 10.1016/S0002-9270(01)02440-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Mitchell CM, et al. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Functional status and patient worries and concerns. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:1379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dunker MS, Bemelman WA, Slors JF, et al. Functional outcome, quality of life, body image, and cosmesis in patients after laparoscopic-assisted and conventional restorative proctocolectomy: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1800–7. 10.1007/BF02234458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dunker MS, Stiggelbout AM, van Hogezand RA, et al. Cosmesis and body image after laparoscopic-assisted and open ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease. Surg Endosc 1998;12:1334–40. 10.1007/s004649900851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eshuis EJ, Polle SW, Slors JF, et al. Long-term surgical recurrence, morbidity, quality of life, and body image of laparoscopic-assisted vs. open ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:858–67. 10.1007/s10350-008-9195-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eshuis EJ, Slors JF, Stokkers PC, et al. Long-term outcomes following laparoscopically assisted versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease. Br J Surg 2010;97:563–8. 10.1002/bjs.6918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eshuis EJ, Voermans RP, Stokkers PC, et al. Laparoscopic resection with transcolonic specimen extraction for ileocaecal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg 2010;97:569–74. 10.1002/bjs.6932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gallo J, Grant A, Otley AR, et al. Do parents and children agree? Quality-of-life assessment of children with inflammatory bowel disease and their parents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:481–5. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Giudici F, Scaringi S, Di Martino C, et al. Rationalisation of the surgical technique for minimally invasive laparoscopic ileal pouch-anal anastomosis after previous total colectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Minim Access Surg 2017;13:188–91. 10.4103/0972-9941.199607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grant A, Kappelman M, Martin C, et al. O-021 A New Domain Structure for the IMPACT-III, a Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Health Reported Quality of Life (HRQOL) Tool. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:S7–S8. 10.1097/01.MIB.0000480111.27190.df [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grant A, Otley A, Escher J. Assessment of IMPACT III emotional and social functioning domain scores in adalimumab-treated paediatric patients with Crohn's disease. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2016;10:S424–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grootenhuis MA, Maurice-Stam H, Derkx BH, et al. Evaluation of a psychoeducational intervention for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;21:430–5. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328315a215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gudlaugsdottir K, Valsdottir EB, Stefansson TB. [Quality of life after colectomy due to ulcerative colitis]. Laeknabladid 2016;102:482–9. 10.17992/lbl.2016.11.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hagan M, Jambaulikar G, Osche-Gauvin K. Sexual function in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results of a web-based health survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:S516. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Joachi G, Milne B. Inflammatory bowel disease: effects on lifestyle. J Adv Nurs 1987;12:483–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01357.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Juan L, Ricardo DLV, Mayte V. Gender differences in stoma-related quality of life in Puerto Ricans with IBD. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:S14. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kjaer MD, Laursen SB, Qvist N, et al. Sexual function and body image are similar after laparoscopy-assisted and open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. World J Surg 2014;38:2460–5. 10.1007/s00268-014-2557-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Knowles SR, Gass C, Macrae F. Illness perceptions in IBD influence psychological status, sexual health and satisfaction, body image and relational functioning: a preliminary exploration using structural equation modeling. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e344–e350. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knowles SR, Wilson J, Wilkinson A, et al. Psychological well-being and quality of life in Crohn's disease patients with an ostomy: a preliminary investigation. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40:623–9. 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182a9a75b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kuruvilla K, Osler T, Hyman NH. A comparison of the quality of life of ulcerative colitis patients after IPAA vs ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:1131–7. 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182690870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee D, Baldassano RN, Otley AR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of nutritional and biological therapy in North American children with active Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1786–93. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liwanag MJ, Liu JX, Tan LN, et al. P-043: Health related quality of life in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in a Southeast Asian population. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2014;8:S409 10.1016/S1873-9946(14)50058-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mason A, Malik S, McMillan M, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of growth and pubertal progress in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Horm Res Paediatr 2015;83:45–54. 10.1159/000369457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maunder R, Toner B, de Rooy E, et al. Influence of sex and disease on illness-related concerns in inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol 1999;13:728–32. 10.1155/1999/701645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mazzoccone A. A study of body image in patients with chronic colon and liver diseases. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali 1980:105–13. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mountifield R, Bampton P, Prosser R, et al. Fear and fertility in inflammatory bowel disease: a mismatch of perception and reality affects family planning decisions. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:720–5. 10.1002/ibd.20839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mukhopadhyay A, Probert S, Smith C. IMPACT III-disease-specific health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for children with Crohn's disease (CD) on infliximab-a single centre experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64 519–20. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Muller KR, Prosser R, Bampton P, et al. Female gender and surgery impair relationships, body image, and sexuality in inflammatory bowel disease: patient perceptions. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:657–63. 10.1002/ibd.21090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Navas-Lopez VM, Martin-De-Carpi J, Grant A. Quality of life in paediatric Crohn's disease: data from the Imagekids study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2016;10:S145–6. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ogden CA, Akobeng AK, Abbott J, et al. Validation of an instrument to measure quality of life in British children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;53:280–6. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182165d10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Perrin JM, Kuhlthau K, Chughtai A, et al. Measuring quality of life in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: psychometric and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;46:164–71. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812f7f4e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Plevinsky JM, Greenley RN. Exploring health-related quality of life and social functioning in adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseases after attending camp oasis and participating in a Facebook group. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1611–7. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Polle SW, Dunker MS, Slors JF, et al. Body image, cosmesis, quality of life, and functional outcome of hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy: long-term results of a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 2007;21:1301–7. 10.1007/s00464-007-9294-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ponsioen CY, de Groof EJ, Eshuis EJ, et al. Laparoscopic ileocaecal resection versus infliximab for terminal ileitis in Crohn's disease: a randomised controlled, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:785–92. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30248-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saha S, Zhao Y-Q, Shah SA, et al. Body image dissatisfaction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:345–52. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Savarino JR, Venkatesh RD, Israel EJ. Health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients receiving infliximab: a pilot study using the impact-III questionnaire. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;63:S362–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Bassi D, et al. Intestinal surgery for Crohn's disease: predictors of recovery, quality of life, and costs. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:2128–35. 10.1007/s11605-009-1044-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Shah S, Urban M, Gracely E. Anonymous self perception survey of sexuality and body image in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:S377–9. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shepanski MA, Hurd LB, Culton K, et al. Health-related quality of life improves in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease after attending a camp sponsored by the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:164–70. 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Swedish E, Blucker RT, Grunow J, et al. Mo1195 severity of illness and quality of life over time in pediatric inflammatory disease patients. Gastroenterology 2015;148:S-635 10.1016/S0016-5085(15)32140-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Trindade IA, Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J. The effects of body image impairment on the quality of life of non-operated Portuguese female IBD patients. Qual Life Res 2017;26:429–36. 10.1007/s11136-016-1378-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vlahou CH, Cohen LL, Woods AM, et al. Age and body satisfaction predict diet adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2008;15:278–86. 10.1007/s10880-008-9125-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Weinryb RM, Gustavsson JP, Barber JP. Personality predictors of dimensions of psychosocial adjustment after surgery. Psychosom Med 1997;59:626–31. 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Weinryb RM, Gustavsson JP, Barber JP. Personality traits predicting long-term adjustment after surgery for ulcerative colitis. J Clin Psychol 2003;59:1015–29. 10.1002/jclp.10191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Werner H, Landolt MA, Buehr P, et al. Validation of the IMPACT-III quality of life questionnaire in Swiss children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:641–8. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zambonin D, Giudici F, Ficari F, et al. P599 Short- and long-term outcome of minimally invasive approach for Crohn’s disease: comparison between single incision, robotic-assisted and conventional laparoscopy. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2018;12 S411–12. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx180.726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kjær MD, Laursen SB, Poornorooz PH. Su1131 sexual function and body image is similar after laparoscopic and open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S-383 10.1016/S0016-5085(14)61379-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jedel S, Hood MM, Keshavarzian A. Getting personal: a review of sexual functioning, body image, and their impact on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:923–38. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pinquart M. Body image of children and adolescents with chronic illness: a meta-analytic comparison with healthy peers. Body Image 2013;10:141–8. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Allison M, Lindsay J, Gould D, et al. Surgery in young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a narrative account. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1566–75. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rosenblum GD, Lewis M. The relations among body image, physical attractiveness, and body mass in adolescence. Child Dev 1999;70:50–64. 10.1111/1467-8624.00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bearman SK, Martinez E, Stice E, et al. The skinny on body dissatisfaction: a longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc 2006;35:217–29. 10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Brennan M, Lalonde C, Bain J. Body image perceptions: do gender differences exist? Psi Chi J Undergrad Res 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Miranda VP, Conti MA, de Carvalho PH, et al. Body image in different periods of adolescence. Rev Paul Pediatr 2014;32:63–9. 10.1590/S0103-05822014000100011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ando S, Osada H. Age and gender differences in body image over the life span: relationships between physical appearance, health and functioning. The Japanese Journal of Health Psychology 2009;22:1–16. 10.11560/jahp.22.2_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Pruis TA, Janowsky JS. Assessment of body image in younger and older women. J Gen Psychol 2010;137:225–38. 10.1080/00221309.2010.484446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Teo I, Cheung YB, TYK L. The relationship between symptom prevalence, body image, and quality of life in Asian gynecologic cancer patients. Psycho-oncology 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Rhondali W, Chisholm GB, Daneshmand M, et al. Association between body image dissatisfaction and weight loss among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:1039–49. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Watson B, Broadbent J, Skouteris H, et al. A qualitative exploration of body image experiences of women progressing through pregnancy. Women Birth 2016;29:72–9. 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hale ED, Radvanski DC, Hassett AL. The man-in-the-moon face: a qualitative study of body image, self-image and medication use in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2015;54:1220–5. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Alleva JM, Sheeran P, Webb TL, et al. A meta-analytic review of stand-alone interventions to improve body image. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139177 10.1371/journal.pone.0139177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel JB, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:829–35. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kochar B, Barnes EL, Long MD, et al. Depression is associated with more aggressive inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:80–5. 10.1038/ajg.2017.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgast-2018-000255supp001.docx (17.3KB, docx)

bmjgast-2018-000255supp002.docx (26.7KB, docx)