Abstract

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the utility of the number needed to treat (NNT) to inform decision-making in the context of paediatric oncology and to calculate the NNT in all superiority, parallel, paediatric haematological cancer, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with a comparison to the threshold NNT as a measure of clinical significance.

Design

Systematic review

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Childhood Cancer Group Specialized Register through CENTRAL from inception to August 2018.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Superiority, parallel RCTs of haematological malignancy treatments in paediatric patients that assessed an outcome related to survival, relapse or remission; reported a sample size calculation with a delta value to allow for calculation of the threshold NNT, and that included parameters required to calculate the NNT and associated CI.

Results

A total of 43 RCTs were included, representing 45 randomised questions, of which none reported the NNT. Among acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) RCTs, 29.2% (7/24) of randomised questions were found to have a NNT corresponding to benefit, in comparison to acute myeloid leukaemia (ALM) RCTs with 50% (3/6), and none in lymphoma RCTs (0/13). Only 28.6% (2/7) and 33.3% (1/3) had a NNT that was less than the threshold NNT for ALL and AML, respectively. Of these, 100% (2/2 ALL and 1/1 AML) were determined to be possibly clinically significant.

Conclusions

We recommend that decision-makers in paediatric oncology use the NNT and associated confidence limits as a supportive tool to evaluate evidence from RCTs while placing careful attention to the inherent limitations of this measure.

Keywords: leukaemia, lymphoma, paediatric oncology, numbers needed to treat, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The utility of the number needed to treat (NNT) was evaluated in all superiority, parallel group, paediatric haematological randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published from inception to August 2018, wherein relapse, remission or survival was assessed.

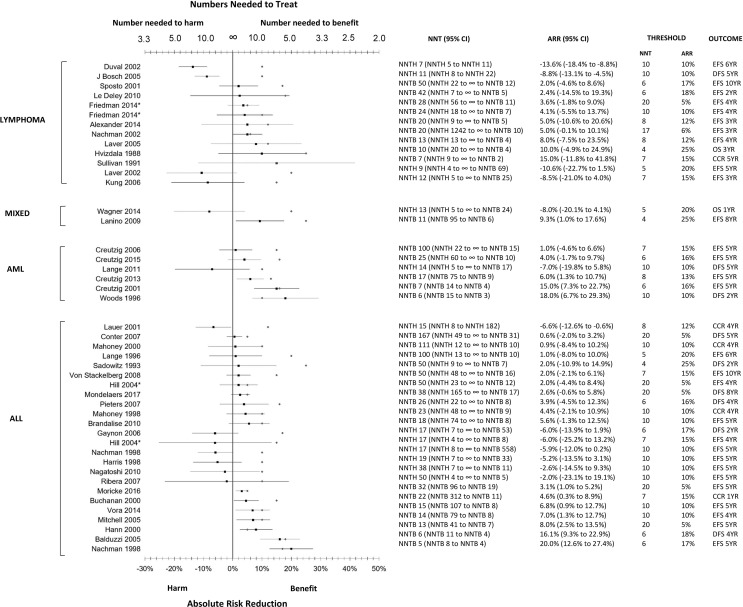

The visualisation, in the form of a forest plot, of the relationship between NNT, CIs and the threshold NNT of all included studies provides a clinically relevant example of communicating complex information.

A number of RCTs were excluded from this review due to reporting that precluded calculating the NNT.

The delta value in the sample size calculation was assumed to be the absolute difference that would provide a clinically significant effect size and a proxy for the threshold NNT. This assumption, thus would lead to the possibility of effect sizes being chosen that might be more reflective of feasibility than clinical benefit and, therefore, limits generalisability, as this is not a universally recognised approach.

The proposed method implies that the threshold NNT is equivalent to the threshold absolute risk reduction (ARR) even though the NNT results in a transformation of scale and is expressed using a unit measured in patients. Therefore, a threshold ARR may not correspond to a minimal clinically important difference in terms of the NNT.

Introduction

Cancer in children is exceedingly rare and consists of less than 1% of all cancers diagnosed in Canada, with haematological cancers accounting for approximately 40% of cases.1 Paediatric haematological cancer survival rates are currently upwards of 80%, largely as a result of treatment advances evaluated through randomised controlled trials (RCTs).2 Owing to the relative rarity of paediatric haematological cancers, multicentre international trials have been necessary to conduct adequately powered treatment investigations.1 3 However, even with coordinated resource-intensive efforts, it can take 5–7 years to complete a phase III RCT, and another 5 years to publish outcomes with meaningful follow-up.2 There is also an additional time lag before high-level evidence becomes the standard of care.2

Given the lengthy timeline from research to practice, evaluating evidence arising from RCTs published in the paediatric oncology literature is critical for informing subsequent RCTs and standard of care. In other treatment contexts, the number needed to treat (NNT) has proven to be of value in assisting clinicians to assess therapeutic interventions and act as a supportive tool in benefit–risk assessments as well as formulary decision-making.4–8 The NNT is an absolute effect measure coined almost 30 years ago, defined as the ’number of patients needed to be treated with one therapy versus another for one patient to encounter an additional outcome of interest within a defined period of time'.6 9 10 The NNT corresponds to the inverse of the absolute risk reduction (ARR), which is the absolute difference between the experimental and control estimates, for a specific time point. For example, an RCT comparing the effect of the medication strontium ranelate to a placebo on the incidence of vertebral fractures at 3 years in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis found that the event rate in the strontium ranelate group was 20.9% compared with 32.8% in the placebo.11 The inverse of the absolute difference in event rates between the experimental and control groups corresponds to the NNT, such that in this study, ’nine patients would need to be treated for 3 years with strontium ranelate in order to prevent one patient from having a vertebral fracture (95 percent CI, 6 to 14)'.11 The evaluation of evidence requires, at a minimum, consideration of the absolute risk and relative benefits (and harms) related to a therapy in question, with the NNT being a supportive tool do so.12 Despite the usefulness of the NNT and the Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement, which considers the NNT as a helpful tool, recent research suggests that these measures are rarely reported in the literature.6 13–16

At this time, the utility of the NNT to support evidence-based practice in paediatric oncology treatment trials remains unexamined, as does the degree to which the NNT has been reported in the paediatric oncology literature. We specifically aimed to assess the utility of the NNT with consideration of a threshold NNT, which is the point where the therapeutic benefit equals the therapeutic risk.17 The threshold NNT should correspond to the inverse of the ARR that an RCT is designed to detect and a clinically significant effect size that would lead to a clinical practice change. Therefore, a decision to administer a therapeutic intervention over the standard of care should occur when the NNT is less than the threshold NNT.17 The primary study objective was to assess the utility of the NNT in paediatric haematological cancer, by calculating the NNT in all superiority, parallel RCTs assessing treatment-related survival, relapse or remission, and comparing the NNT to the threshold NNT. A secondary study objective was to assess the proportion of published studies (specifically randomised questions) that reported the NNT.

Methods

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (online supplementary file).18 This review consisted of a subset of studies from a previous systematic review conducted by our research team, which was conducted from inception of the databases searched to July 2016. The search strategy used in that systematic review was re-run to capture studies published from July 2016 to August 2018. Methods describing the search strategy, eligibility criteria, study identification and data extraction for our previous systematic review have been detailed in the protocol (online supplementary file–appendix A).

bmjopen-2018-022839supp001.pdf (103.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022839supp002.pdf (657.5KB, pdf)

Search strategy and study inclusion

A comprehensive literature review was performed using the databases MEDLINE (Via Ovid), EMBASE (via OVID) and Cochrane Childhood Cancer Group Specialized Register (via CENTRAL) from inception to August 2018 to identify all superiority, parallel group RCTs in paediatric patients diagnosed with a haematological cancer that assessed an outcome related to survival, relapse or remission and those that reported either CIs or standard errors associated with both the experimental and control estimates, or number of patients at risk on a Kaplan–Meier curve. The reference lists of included studies during the full-text review stage were hand-searched to identify any additional studies. The search was restricted to studies published in English and therefore prone to language bias.

Study identification and data extraction

Two investigators (HH and KN) screened the titles and abstracts non-independently to identify studies that fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were settled by discussion and consensus, with the principal investigator (AFH) available as an adjudicator. Studies that fulfilled the inclusion criterion at the title and abstract screening stage were selected for full-text review by one investigator (HH) to confirm study eligibility. A data extraction template was developed and piloted with 15 included studies to ensure all pertinent data were captured. One investigator (HH) then extracted all of the data, of which a random sample was selected and verified by the principal investigator (AFH) as a quality assurance measure.

Analysis

The number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB), which corresponds to a positive NNT, or number needed to treat to harm (NNTH), which corresponds to a negative NNT, and associated 95% CI were calculated for each randomised question as per the validated methodology described by Altman & Andersen.19 A randomised question is defined as an intervention comparison assessing a primary outcome for which a sample size calculation is reported. The NNT was based on the primary outcome and time point as specified in the sample size calculation. In the event that the time point specified in the sample size calculation was not reported, the information was inferred if a Kaplan–Meier curve with the number of patients at risk was reported.19 If the aforementioned was not provided, the time point reported in the results was used, and thus, these trials were prone to selective reporting bias. All analyses were conducted based on randomised questions to account for the possibility that an RCT could have more than one parallel group.

The ARR, NNT and delta values (ie, threshold ARR and NNT), as reported in the sample size calculation, were visualised on a forest plot, grouped by disease (acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), lymphoma and mixed, which corresponds to the inclusion of multiple diseases), to allow for identification of NNTB (defined as the NNT and 95% CI that only included positive numbers), NNTH (defined as the NNT and 95% CI that only included negative numbers) and inconclusive NNT (defined as the NNT where the 95% CI included both a positive number and a negative number). Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the frequency and percentage of randomised questions reporting the NNT, as well as the NNTB, NNTH and inconclusive NNT by disease site.

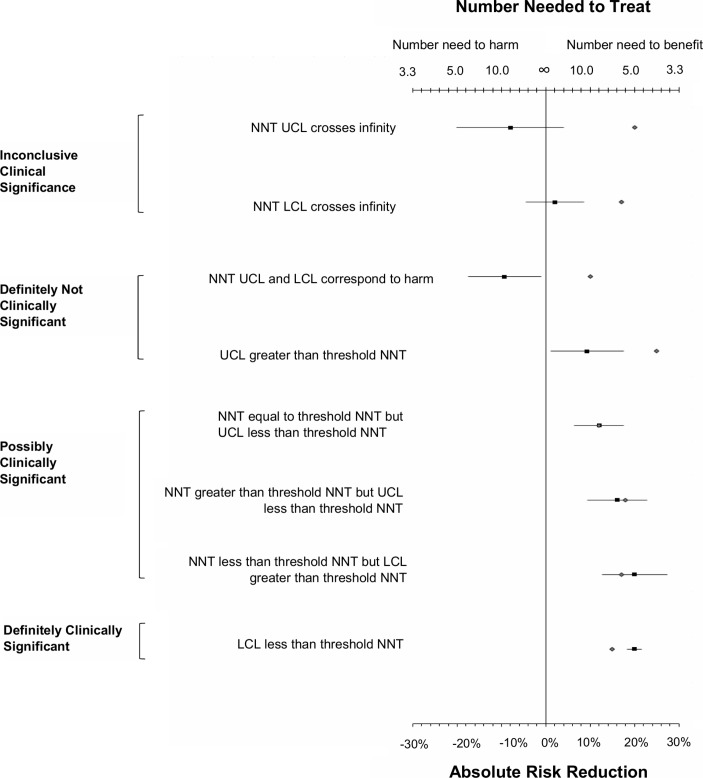

In order to ascertain whether the NNTB was clinically significant, we calculated the frequency and percentage of randomised questions where the NNT <threshold NNT, NNT >threshold NNT or NNT=threshold NNT. The threshold NNT was considered to be the inverse of the ARR (ie, delta value), as specified in the sample size calculation, and was assumed to correspond to a clinically significant effect size that would lead to a change in clinical practice. The threshold NNT was compared with the treatment NNT and classified as definitely clinically significant, possibly clinical significant, inconclusive clinical significance and definitely not clinically significant as specified in figure 1. These categories, as well as the overall method, were informed by methods described by Man-Son-Hing et al 20 and Guyatt et al.21RCTs where an ARR of zero occurred were excluded from the analysis because the inverse corresponds to an undefined NNT. SAS (Statistical Analysis Software) version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform all analyses.

Figure 1.

Guideline to assess level of clinical significance using NNT. Grey diamond refers to the delta value for the threshold ARR or NNT while the black square to the study ARR or NNT. ARR corresponds to the absolute difference between the experimental and control estimates. The inverse of the ARR corresponds to the NNT. The threshold ARR corresponds to the delta value, and the randomised control trial was designed to detect as determined in the sample size calculation. The inverse of the threshold ARR corresponds to the threshold NNT. ARR, absolute risk reduction; LCL, lower confidence limit; NNT, number needed to treat; UCL, upper confidence limit.

Patient and public involvement

Given this is a research methods systematic review, there was no patient or public involvement.

Results

Included studies

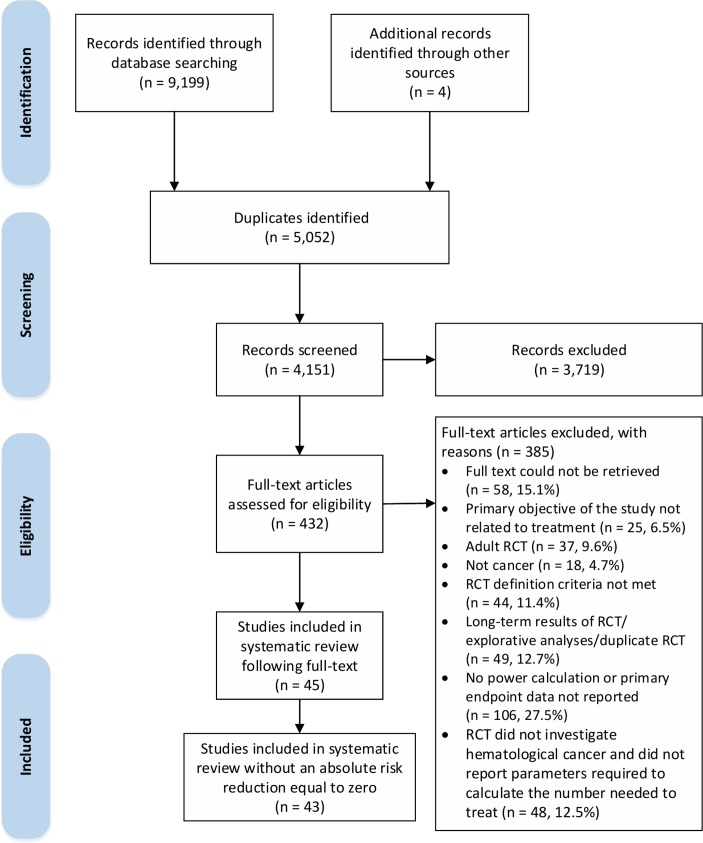

Our search identified 4151 unique studies from MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Childhood Cancer Group Specialized Register accessed through CENTRAL. Following title and abstract screening, 432 studies were evaluated for eligibility based on full-text review. Of these studies, 387 studies were excluded and 43 studies (ie, RCTs), representing 45 randomised questions, were included in the systematic review (figure 2) (online supplementary file–appendix B). The randomised questions corresponded to RCTs investigating treatments for ALL (n=24; 53.3%), lymphoma (n=13; 28.9%), AML (n=6; 13.3%) and mixed diagnoses (n=2; 4.4%).

Figure 2.

Selection of RCTs in the systematic review. RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

Number needed to treat

The frequency and proportion of the NNTB, inconclusive NNT and NNTH are summarised in table 1. Approximately 29.2% (7/24) of randomised questions in ALL RCTs were found to have a NNT corresponding to a NNTB, in comparison to AML with 50.0% (3/6). There were no randomised questions in lymphoma (n=15) trials with a NNTB.

Table 1.

Randomised questions corresponding to number needed to benefit, harm and inconclusive relative to threshold NNT by haematological cancer type

| NNT* | Haematological cancer randomised questions (n=45) | |||

| ALL (n=24) |

Lymphoma (n=13) |

AML (n=6) |

Mixed diagnoses† (n=2) |

|

| NNTB | 7 (29.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| NNTB<threshold NNT | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (100.0%) |

| NNTB lower confidence limit≥threshold NNT | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| NNTB>threshold | 5 (71.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| NNTB upper confidence limit≤threshold NNT | 4 (80.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| NNTB=threshold NNT | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Inconclusive NNT | 16 (66.7%) | 11 (84.6%) | 3 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| NNTH | 1 (4.2%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Threshold NNT corresponds to the inverse of the absolute difference (ie, delta value) as reported in the sample size calculation.

*Denominator for indented corresponds to above row.

†Mixed diagnoses refer to RCTs where more than one haematological cancer was included.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; NNT, number needed to treat; NNTB, number needed to treat to benefit; NNTH, number needed to treat to harm; RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

Comparison of NNT and threshold NNT

A comparison of the NNT to the threshold NNT is summarised in table 1 and visualised in figure 3. For randomised questions corresponding to NNTB, the NNT was less than the threshold NNT in 28.6% (2/7) ALL and 33.3% (1/3) AML comparisons. However, of these, 100% (2/2 and 1/1) had a lower confidence limit that was greater than or equal to the threshold NNT for ALL and AML, respectively, and hence were possibly clinically significant. In contrast, 71.4% (5/7) and 66.7% (2/6) had a NNT greater than the threshold NNT; however, 80.0% (4/5) and 50.0% (1/2) of these had an upper confidence limit that was less than or equal to the threshold NNT for ALL and AML, respectively, and hence were possibly clinically significant.

Figure 3.

Forest plot summarising randomised questions by the number needed to treat relative to the threshold number needed to treat according to haematological cancer type. *Correspond to RCT where more than one randomised question was investigated. Grey diamond refers to the delta value for the threshold ARR or NNT while the black square to the study ARR or NNT. ARR corresponds to the absolute difference between the experimental and control estimates. The inverse of the ARR corresponds to the NNT. The threshold ARR corresponds to the delta value, and the randomised control trial was designed to detect as determined in the sample size calculation. The inverse of the threshold ARR corresponds to the threshold NNT. AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; ARR, absolute risk reduction; CCR, complete cancer remission; DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; NNT, numbers needed to treat; NNTB, number needed to benefit; NNTH, number needed to harm; OS, overall survival; RR, relapse rate; YR, year.

Reporting of NNT

There were no randomised questions that reported the NNT to support the reporting of the primary outcome of the study.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we demonstrated that variation in the NNT exists among RCTs assessing outcomes related to remission, relapse and survival in paediatric haematological cancers. A majority of randomised questions found to have a NNTB were not necessarily associated with a positive effect size when using the inverse of the delta value as specified in the sample size calculation as a proxy for the threshold NNT and a measure of what a clinically significant NNT should be. There were no randomised questions reporting the NNT, which highlights reporting deficits in the paediatric haematological cancer RCT literature.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our review provides a comprehensive analysis of the utility of the NNT through an evaluation of all superiority, parallel group paediatric haematological RCTs assessing relapse, remission and survival from inception to August 2018. We provide the NNT and ARR with its 95% CI along with the threshold NNT and ARR for these RCTs using a validated methodological approach, which will serve as a valuable tool for decision-makers, clinicians and researchers to assess treatment effects. A weakness of this study is the exclusion of a number of RCTs due to reporting that precluded calculating the NNT. However, as the exclusion is due to reporting deficits, this limitation is beyond our control and serves as an important finding that reporting quality is limited in the paediatric haematological cancer RCT literature. An additional weakness is that the delta value in the sample size calculation was assumed to be the absolute difference that would provide an effect size that would lead to a change in clinical practice (ie, minimal clinically important difference), if not explicitly indicated, and a proxy for the threshold ARR and NNT. This assumption, thus, would lead to the possibility of effect sizes being chosen that might be more reflective of study feasibility as opposed to clinical benefit. This approach may be limited in terms of generalisability given that this is not a universally recognised approach. Additionally, this assumption implies that the threshold NNT is equivalent to the threshold ARR even though the NNT results in a transformation of scale and is expressed using a unit measured in patients. Therefore, a threshold ARR may not correspond to a minimal clinically important difference in terms of NNT. However, as there were no studies that reported a threshold NNT, our approach represents a feasible method to apply in the absence of a reported threshold NNT. This method is nonetheless not validated and further studies will need to be undertaken to compare whether researchers would equate the minimal clinical important difference in terms of ARR to the NNT.

Comparison with existing literature

Considerable published literature has evaluated the utility of the NNT. The overarching conclusion is that the NNT is a metric of value in clinical, health policy and formulary decision-making when interpreted correctly.4–8 However, the NNT and ARR are rarely reported or poorly reported in the literature despite being recommended as a helpful tool in the CONSORT statement and are often calculated using inappropriate methods.6 12–16 22–27 Our findings corroborate the existing literature because no studies reported the NNT in our review. Previous studies have not highlighted the utility of the NNT specifically in the paediatric oncology literature or evaluated the clinical significance of the NNT using the approach described in our study and thus, our study is a novel and important addition to the literature.

Study explanations and implications

Our study quantified the NNT as a means to better understand the utility of this tool to facilitate decision-making in paediatric oncology. The NNT allows for an intuitive understanding of the absolute effect size in terms of patients and can help considerably when comparing one treatment to another, after ensuring baseline characteristics, the outcome and time point for the patient population of interest are comparable.12 For instance, an RCT conducted by Creutizig et al 28 in paediatric AML patients assessing 5-year event-free survival found a 6.0% (95% CI, 1.3% to 10.7%) absolute increase associated with the experimental treatment (liposomal daunorubic induction) compared with the control treatment (idarubicin induction). The associated NNT corresponded to 17 (95% CI; 75 to 9) or NNTB 17 (95% CI, NNTB 75 to NNTB 9), meaning that it is estimated that by administering the experimental treatment, one extra patient would survive at 5 years for every 17 patients treated (95% CI, NNTB 75 to NNTB 9). Of note, this RCT was powered to detect an absolute increase in 5-year event-free survival of 13% (ie, delta value), which would correspond to a NNTB of 8 (ie, threshold NNT). Although the NNTB is 17, the lower confidence limit is 75 and the upper confidence limit is 9 (a range that does not include 8), which, given the range, would lead one to believe that the effect size does not provide strong enough evidence to change clinical practice. In situations where the lower confidence limit of the NNTB is less than the threshold NNT, one can be more confident that the treatment confers a clinically improved outcome as compared with the control. On the other hand, if the NNTB is less than the threshold NNT and the lower confidence limit is greater than the threshold NNT, one should exercise greater caution in concluding that the effect size is clinically significant (refer to figure 1 for visual). As demonstrated in our study, a forest plot is a convenient method to visualise the relationship between the NNT (and the associated 95% CI), evident in study results, compared with the NNT that the study was designed to detect as a proxy for the threshold NNT and that would be considered clinically significant.

The aforementioned approach is recommended in light of smaller sample sizes that are often attained in paediatric oncology RCTs and rare disease trials in general, as it allows for assessment of the precision of the treatment effect as well as clinical and statistical significance. This was demonstrated in our study where the majority of randomised questions found to have a NNTB had a NNT greater than the threshold NNT, of which the upper confidence limit was less than or equal to the threshold NNT. If these RCTs were designed with higher power, it is possible that definite clinical significance may have been obtained. On the other hand, these findings would not be considered significant based on statistical significance. Since statistical significance does not provide an indication of the size of the treatment effect, one would not be able to discern whether the findings could have possible clinical significance. An assessment of clinical significance, therefore, requires a summary measure be presented with a CI. By presenting a CI, an assessment can be made of both statistical and clinical significance, which can inform clinical decision-making. Interpreting results from RCTs based solely on statistical significance, without taking into consideration clinical significance, can result in misappraisal of evidence. Using the results of our study as an example, we demonstrated that all randomised questions, for which the NNTB was less than threshold NNT, had a lower confidence limit that was equal to, or greater than, the threshold NNT. Although these results were statistically significant, none had definite clinical significance and were only possibly clinically significant. These findings have clinical implications because clinicians often have to make decisions about administering treatments that are not standard of care, and rely on an accurate appraisal of evidence to inform these decisions. Inconclusive evidence, however, does not necessarily infer an ineffective intervention. Rather, inconclusive evidence (when the CI of the NNT crosses infinity as a result of the CI of the ARR crossing 0) infers that the level of clinical significance cannot be determined from the study results. The use of the NNT and the method we describe can be one more tool to support clinical decision-making within this context.

The scenarios where the NNT results in inconclusive evidence is a limitation in the utility of NNT, as discussed by Altman.29 To illustrate, Lange et al 30 assessed 5-year disease-free survival in paediatric AML patients in first remission after intensive chemotherapy, and found a 7.0% (95% CI, −19.8% to 5.8%) absolute decrease associated with the experimental treatment (interleukin-2 infused on days 0–3 and 8–17) compared with the control treatment (no further therapy). The study was powered to detect a 10% difference in 5-year disease-free survival, which was assumed to be the minimal clinical importance difference, and hence, corresponds to a threshold NNTB of 10. The resulting NNT of the RCT was −14 (95% CI, −5 to 17) or a NNTH 14 (95% CI, NNTH 5 to NNTB 17). At first glance, it appears as though the point estimate does not fall within the 95% CI, given the disjointed confidence limits. In other studies wherein the CI traverses both harm and benefit the NNT is reported without the CI.31 In reality, the CI encompasses values from a NNTH of 5 to ∞ and NNTB of 17 to ∞. Plotting the NNT and CI on a forest plot (figure 3) demonstrates that a NNTH of 14 does fall within the interval range and in fact, the interval is continuous. Altman, therefore, recommended presenting the CI of the NNT as the following to emphasise continuity (using results from Lange et al as an example): NNTH 14 (NNTH 5 to ∞ to NNTB 17).

We strongly encourage plotting the ARR and the NNT on a forest plot simultaneously because the NNT is simply a method of re-expressing the ARR and supports the interpretation of the ARR. As the NNT is a relative measure, it should always be accompanied by the absolute measure, the ARR.16 Additionally, the utility of the NNT is inherently reliant on three major areas: baseline risk, the outcome and the time point.12 In order for the NNT from an RCT demonstrating a NNTB to have utility, the patient population of interest should share a similar baseline risk because the desired treatment effect may be overestimated and thus the NNTB may by underestimated. Outcomes related to event-free survival often differ in what is considered an event and thus it is critical to ensure that the NNTB being applied to the population of interest is identical in terms of the outcome in question. Numerous studies have demonstrated how the NNT varies with time and thus, comparability in time points is critical to ensure accurate interpretation of the NNT to a population of interest.4 12 23 24 Lastly, criticisms of the statistical properties of the NNT have been highlighted by Hutton32 33 and Katz et al.34 We agree with Altman & Deeks’s32 response to these criticisms in that the NNT was designed for translation of research results and, therefore, arguments related to computation and its distribution properties are of less relevance. The NNT is simply a metric to re-express the ARR and, therefore, should be viewed as a measure to support the interpretation of the ARR.

Recommendations

We recommend that clinicians and decision-makers in paediatric oncology consider using the NNT as a supportive tool to evaluate evidence from RCTs while paying careful attention to the inherent limitation of this measure. Additionally, we recommend that researchers report the NNT and associated CI to support the interpretation and generalisability of the trial results. Given the inherent limitations of the NNT, we emphasise that the NNT should be considered a supportive tool to inform evidence-based decision-making and not a replacement. Online supplementary file appendix C provides a summary of how the NNT can be calculated and assessed to inform decision-making.19 20

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: AFH, KG and HH conceived and designed the study. HH collected and analysed the data. AFH and HH wrote the first drafts of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to subsequent drafts. All authors had full access to all of the data in the review and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: Funding support was provided by the University of British Columbia School of Nursing to conduct this systematic review.

Disclaimer: The funder played no role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. They accept no responsibility for the contents.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Unpublished data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society, 2017. cancer.ca/Canadian-CancerStatistics-2017-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saletta F, Seng MS, Lau LM. Advances in paediatric cancer treatment. Transl Pediatr 2014;3:156–82. 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2014.02.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bond MC, Pritchard S. Understanding clinical trials in childhood cancer. Paediatr Child Health 2006;11:148–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67:407–11. 10.1111/ijcp.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mendes D, Alves C, Batel Marques F. Testing the usefulness of the number needed to treat to be harmed (NNTH) in benefit-risk evaluations: case study with medicines withdrawn from the European market due to safety reasons. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:1301–12. 10.1080/14740338.2016.1217989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mendes D, Alves C, Batel-Marques F. Number needed to treat (NNT) in clinical literature: an appraisal. BMC Med 2017;15:112 10.1186/s12916-017-0875-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mendes D, Alves C, Batel-Marques F. Number needed to harm in the post-marketing safety evaluation: results for rosiglitazone and pioglitazone. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:1259–70. 10.1002/pds.3874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mendes D, Alves C, Batel-Marques F. Benefit-risk of therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: testing the Number Needed to Treat to Benefit (NNTB), Number Needed to Treat to Harm (NNTH) and the Likelihood to be Helped or Harmed (LHH): a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 2016;30:909–29. 10.1007/s40263-016-0377-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1728–33. 10.1056/NEJM198806303182605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995;310:452–4. 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meunier PJ, Roux C, Seeman E, et al. . The effects of strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2004;350:459–68. 10.1056/NEJMoa022436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McAlister FA. The “number needed to treat” turns 20-and continues to be used and misused. CMAJ 2008;179:549–53. 10.1503/cmaj.080484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hildebrandt M, Vervölgyi E, Bender R. Calculation of NNTs in RCTs with time-to-event outcomes: a literature review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:21 10.1186/1471-2288-9-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Chang D. Reporting number needed to treat and absolute risk reduction in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2002;287:2813 10.1001/jama.287.21.2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alonso-Coello P, Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R, et al. . Systematic reviews experience major limitations in reporting absolute effects. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;72:16–26. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF. C. explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;2010:340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinclair JC, Cook RJ, Guyatt GH, et al. . When should an effective treatment be used? Derivation of the threshold number needed to treat and the minimum event rate for treatment. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ 1999;319:1492–5. 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Rourke K, et al. . Determination of the clinical importance of study results. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:469–76. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11111.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, et al. . Users' guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 1995;274:1800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suissa S. Number needed to treat in COPD: exacerbations versus pneumonias. Thorax 2013;68:540–3. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suissa S. The number needed to treat: 25 years of trials and tribulations in clinical research. Rambam Maimonides Med J 2015;6:e0033 10.5041/RMMJ.10218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suissa D, Brassard P, Smiechowski B, et al. . Number needed to treat is incorrect without proper time-related considerations. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:42–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stang A, Poole C, Bender R. Common problems related to the use of number needed to treat. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:820–5. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tramèr MR, Walder B. Number needed to treat (or harm). World J Surg 2005;29:576–81. 10.1007/s00268-005-7916-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Molnar FJ, Man-Son-Hing M, Fergusson D. Systematic review of measures of clinical significance employed in randomized controlled trials of drugs for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:536–46. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Bourquin JP, et al. . Randomized trial comparing liposomal daunorubicin with idarubicin as induction for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: results from Study AML-BFM 2004. Blood 2013;122:37–43. 10.1182/blood-2013-02-484097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ 1998;317:1309–12. 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lange BJ, Yang RK, Gan J, et al. . Soluble interleukin-2 receptor α activation in a Children’s Oncology Group randomized trial of interleukin-2 therapy for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:398–405. 10.1002/pbc.22966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Using numerical results from systematic reviews in clinical practice. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:712–20. 10.7326/0003-4819-126-9-199705010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hutton JL. Number needed to treat: properties and problems. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2000;163:381–402. 10.1111/1467-985X.00175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hutton JL. Number needed to treat and number needed to harm are not the best way to report and assess the results of randomised clinical trials. Br J Haematol 2009;146:27–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Katz N, Paillard FC, Van Inwegen R. A review of the use of the number needed to treat to evaluate the efficacy of analgesics. J Pain 2015;16:116–23. 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022839supp001.pdf (103.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022839supp002.pdf (657.5KB, pdf)