Abstract

The primary objective of this study was to identify risk factors associated with becoming susceptible to e-cigarette use over the course of a year among e-cigarette-naive adolescents considering a comprehensive model of risk factors (risk perceptions, social influences and norms, affective risk factors, and other behavioral risk factors). Data came from the Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance system (TATAMS), a longitudinal cohort study of students who were in the 6th, 8th, and 10th grades (n = 3907) during the 2014–2015 academic year. Weighted generalized linear mixed models assessed multiple predictors’ associated with the transition to susceptibility to e-cigarettes at 12 months. Among 6th graders, family influence, use of other substances, and positive affect were important. Adolescents transitioning from 8th grade to high school presented the greatest number of risk factors (e.g., social and normative influences). Only sensation seeking increased the risk of susceptibility to e-cigarettes among 10th graders. Overall, by grade level, incidence of susceptibility to e-cigarettes at 12 months did not vary, but risk factor profiles varied substantially.

Keywords: Susceptibility, E-cigarette, Adolescents

1. Introduction

Among adolescents of all ages, susceptibility is a strong predictor of future initiation of (Jackson & Dickinson, 2004; Jackson, Henriksen, Dickinson, Messer, & Robertson, 1998), experimentation with (Jackson et al., 1998; Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merritt, 1996; Spelman et al., 2009; Unger, Johnson, Stoddard, Nezami, & Chou, 1997), and ever (Gritz et al., 2003) or current (Jackson & Dickinson, 2004) cigarette smoking. Literature specific to e-cigarette use and this construct are just emerging. Notably, recent data suggest that e-cigarette susceptibility among cigarette-and e-cigarette-naïve (never smoker) adolescents is an independent predictor of future initiation and past 30-day use of e-cigarettes (Bold, Kong, Cavallo, Camenga, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2016). E-cigarette use is associated with the transition to cigarette smoking (USDHHS, 2016), and further, more frequent e-cigarette use is associated with an incrementally higher risk of more frequent and heavier cigarette smoking (Leventhal et al., 2016).

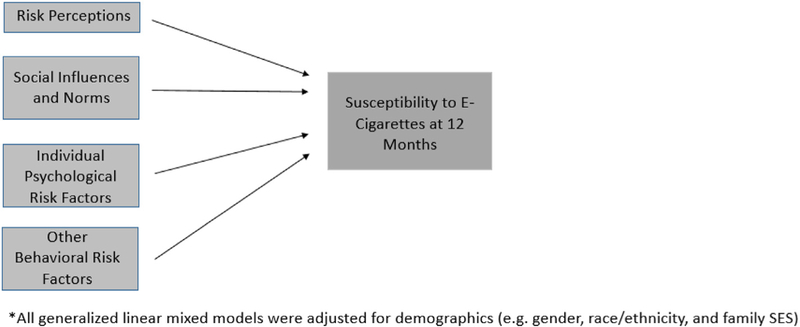

While a large volume of research has identified risk factors associated with susceptibility to cigarette use among youth (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) and the literature identifying risk factors for e-cigarette use is emerging (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016), less attention has been paid to the transition to e-cigarette susceptibility. Strong et al. (2015) advocate for exploration of factors associated with transitions across smoking trajectory pathways as such studies would identify risk factors among e-cigarette non-users and yield useful information to inform the development of evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies. Examining the diverse risk factors associated with e-cigarette use will start to fill this gap. These factors include risk perceptions, such as harm and addictiveness (Tyas & Pederson, 1998), social influences from family and friends and normative beliefs, and individual affective characteristics, such as depression and sensation seeking (Wellman et al., 2016) (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model for risk factors affecting the transition to E-cigarette susceptibility.

E-cigarettes are the most prevalent tobacco product currently used among adolescents (DHHS, 2016). Since 2011, the prevalence of past-30-day e-cigarette use has more than tripled, rising from 1.5% among high school students to 16% in 2015, and leveling off in 2016 (Jamal et al., 2017). Currently, to the best of our knowledge, no published studies have identified risk factors associated with becoming susceptible to using e-cigarettes among youth. Thus, the goal of the current analysis was to identify risk factors associated with becoming susceptible to e-cigarette use over one-year of follow-up among 6th, 8th, and 10th grade students in Texas who were e-cigarette naive (i.e. non-susceptible, never users of e-cigarettes) at baseline. We stratified analyses by grade level in order to identify whether risk factors associated with the transition to becoming susceptible during early-to-late adolescence vary across these developmental sub-groups (6th grade: early adolescence; 8th grade: middle adolescence; 10th grade: late adolescence) (Barrett & E., 1996) and, similarly, because most intervention strategies typically vary by grade level (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). We used a comprehensive model to assess multiple risk factors with potential influences on e-cigarette use in order to account for potential shared variance and determine which factors are most influential at each grade level and, thus, provide most leverage for intervention strategies that target e-cigarette use among youth.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

The Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance system (TATAMS) is a rapid response surveillance system collecting data from three cohorts of students in five counties surrounding the four largest cities in Texas (Austin, Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas/Fort Worth). Baseline data were collected in the classroom during the 2014–2015 academic year from 3907 students in the 6th, 8th, and 10th grades using computerized surveys administered via tablets. Follow-up data have been collected outside of school every six months since baseline using similarly formatted web-based surveys. Survey items were adapted from state and national tobacco surveillance measures (e.g., the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH)) study (Hyland et al., 2017) that have been shown to be reliable and valid. The sampling methodology and study design of TATAMS is detailed elsewhere by Pérez et al. (2017).

The sample for this analysis was limited to 1369 adolescents classified as e-cigarette-naïve at baseline (Wave 1) with complete data on all demographic and risk variables that reported their susceptibility status at 12 month follow-up (Wave 3), examined as three separate cohorts based on the grade level at baseline (6th, 8th, or 10th). We defined e-cigarette-naivety as both reporting never having tried an e-cigarette and being non-susceptible to e-cigarettes at the time of the baseline survey. Data were weighted, allowing the study population to be representative of 228,556 students enrolled in the 6th, 8th, and 10th grades at baseline in these five Texas counties (Pérez et al., 2017).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Susceptibility

Susceptibility to e-cigarettes was assessed at each wave by three items adapted from Pierce et al. (1996); Pierce, Distefan, Kaplan, and Gilpin (2005); two of the three items have been validated in adolescents by Bold et al. (2016), and the three-item composite measure has been used by others (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016). Adolescents were asked, “Have you ever been curious about using e-cigarettes?”, “Do you think you will use e-cigarettes in the next 12 months?”, and “If one of your close friends were to offer you an e-cigarette, would you use it?” Response options for the first item included, “Not at all curious,” “A little curious,” “Somewhat curious,” or “Very curious”; response options for the remaining two items were, “Definitely not”, “Probably not,” “Probably yes,” or “Definitely yes.” For each individual item, adolescents were categorized as non-susceptible if they responded “Not at all curious” or “Definitely not” to all three items, susceptible if they had any other response, and missing if they were missing on any item.

2.2.2. Risk perceptions

Risk perceptions of the addictiveness of e-cigarettes were assessed by asking, “How addictive are e-cigarettes?” responses dichotomized as “Not at all addictive” versus “Any perceived addictiveness”. One item, “How harmful are [e-cigarettes] to health?” assessed risk perceptions of the harmfulness of e-cigarettes on an ordinal scale ranging from 1 (not at all harmful) to 4 (extremely harmful).

2.2.3. Social influences and norms

Social influences from family were assessed by asking participants, “Does anyone who lives with you now (mother, father, siblings, etc.) use e-cigarettes?” with responses dichotomized as “Yes” or “No/I don’t know.” Friend influence was assessed by asking, “How many of your close friends use e-cigarettes?” with response options dichotomized as “None” versus “Any friends.”

Three social norms about e-cigarettes were assessed using one item each. Participants were asked, “Do you think it is okay for people your age to use e-cigarettes?” Based on the distribution of participant responses, response options were dichotomized as No (“Definitely not”) or Yes (“Probably not,” “Probably yes,” and “Definitely yes”). The remaining social norms were assessed using two items, “How common is it for people your age to use e-cigarettes?” with response options of 1 (not common at all) to 5 (very common), and “I would date someone who uses e-cigarettes,” measured using a five point Likert scale to assess agreement from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.”

2.2.4. Individual psychological risk factors

Positive affect assessment was based on four items adapted from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), asking participants to rate on a five point Likert scale their agreement with the following statements: “I am satisfied with life,” “I am happy,” “I am optimistic or hopeful about the future,” and “I feel enthusiastic or excited.” Positive affect scores were derived from the mean of each participants’ responses to each item. If participants did not respond to three or more items, positive affect score was set to missing.

We did not assume a priori that standard measures of negative affect used for tobacco research would be the most appropriate to use in our study. Rather we chose a more general measure of emotional problems, which had demonstrated an association with tobacco use over a ten-year period (Sourander et al., 2012). Accordingly emotional problems were measured using the five-item emotional problem subscale on Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Muris, Meesters, & van den Berg, 2003), which asks participants to rate how things have been for them over the last six months (e.g., “I get a lot of headaches, stomach-aches or sickness,” “I worry a lot” and “I am often unhappy”). Each item is scored on a 3-point scale with 0 = ‘not true,’ 1= ‘some-what true,’ and 2 = ‘certainly true.’ The SDQ subscale score is computed by averaging scores on the five items, multiplying the score by 5, and rounding to the nearest whole number (EHCAP, 2014). Scores range between 0 and 10, with higher score reflecting more emotional problems. If participants did not respond to four or more items, their emotional problem score was set to missing.

Sensation seeking was assessed using the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (Stephenson, Hoyle, Palmgreen, & Slater, 2003), which assessed agreement with four items using a five-point Likert scale (e.g., “I would like to explore strange places” and “I prefer friends who are exciting and unpredictable”). Sensation seeking scores were derived from the mean of each participants’ responses to each item. If participants failed to respond to three or more items, their sensation seeking score was set to missing.

2.2.5. Other behavioral risk factors

School performance was assessed by asking, “On average, what grades did you get in school last semester?” dichotomized as “Mostly A’s or B’s” versus “Mostly C’s, D’s, and F’s”. Other substance use was assessed based on past 30-day alcohol, marijuana, and combustible tobacco product (cigarettes, hookah, and cigars) use. Participants were dichotomized into those who reported use of at least one of these five products versus no use, in the past thirty days. In the multivariate analysis, we replaced past 30-day combustible tobacco product use with ever combustible tobacco product use to examine substance use, because only five participants included in the current analysis reported past 30-day combustible product use.

2.2.6. Demographics

Demographic variables included sex, race/ethnicity, and family socioeconomic status (SES). Race/ethnicity was categorized as White/Other, Black, or Hispanic using a six-response-option item asking adolescents which races they consider themselves to be and one yes/no item assessing Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Family SES was assessed with one item asking, “In terms of income, what best describes your family’s standard of living in the home where you live most of the time?” with response options of high (“very well off”), middle (“living comfortably”), and low (“just getting by,” “nearly poor,” and “poor”) (Gore, Aseltine, & Colton, 1992; Romero, Cuéllar, & Roberts, 2000; Springer, Selwyn, & Kelder, 2006).

3. Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of risk factors and demographic variables at baseline and susceptibility at 12 month follow-up among e-cigarette naïve adolescents (i.e. non-susceptible, never users of e-cigarettes) at baseline, at each specific grade level. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables were used to examine significant differences in the distribution of each variable across grade levels.

To examine which risk factors at baseline predicted the transition to susceptibility to e-cigarettes 12 months in the future, weighted generalized linear mixed models were used (via PROC GLIMMIX). To account for potential shared variance, all risk factors were included simultaneously in each generalized linear mixed model. Adaptive quadrature, which is an option in SAS that reduces the computational burden when calculating the maximum likelihood function in datasets with complex sampling design (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2006), was used to compute the weighted pseudolikelihood and classical empirical variance estimators to obtain robust standard errors. To account for the use of the dichotomous susceptibility outcome variable, all models utilized a binomial distribution and logit link function. Sampling weights, which accounted for the complex survey design of clustering of students within schools and stratified schools based on proximity to retail point of sale outlets within 0.5 miles, were adjusted for nonresponse to obtain accurate population-level estimates (Pérez et al., 2017).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

At baseline, gender was equally distributed and approximately half of adolescents were of Hispanic ethnicity among each of the three grade levels (Table 1). Family SES showed significant differences across grade levels, with a higher proportion of 10th graders being of a low SES (20.3%) compared to 6th (9.7%) and 8th (14.8%) graders (p < 0.05). As with most longitudinal research, attrition was greater between baseline and the first six-month follow-up, than between the first six-month and the second follow-up: 64% of the baseline sample was retained at six-months, and 70% of baseline was retained at twelvemonths. There were no differences in the tobacco use behaviors between those who did and did not participate in the six-month follow-up (Pérez et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and risk factors among adolescents non-susceptible to E-cigarettes at baseline, by grade (n = 1369; N = 228,556).

| Risk factors | Variable | 6th Grade (n = 526; N = 99,985) | 8th Grade (n = 478, N = 76,556) | 10th Grade (n = 365, N = 52,014) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Gender | Female | 50.0 (37.0– 63.0) | 46.4 (38.3–54.4) | 42.2 (32.7–51.6) |

| Male | 50.0 (37.0– 63.0) | 53.6 (45.6–61.7) | 57.8 (48.4–67.3) | ||

| Ethnicity | White/Other | 36.6 (25.8– 47.4) | 31.9 (20.2–43.6) | 33.2 (24.5–41.8) | |

| Hispanic | 52.1 (40.0– 64.1) | 50.5 (38.8–62.1) | 47.7 (36.9–58.6) | ||

| Black | 11.3 (5.9–16.7) | 17.6 (9.1–26.2) | 19.1 (11.4–26.8) | ||

| Family SES* | Low | 9.7 (7.2–12.2) | 14.8 (8.2–21.4) | 20.3 (14.5–26.1) | |

| Middle | 65.7 (61.0– 70.4) | 62.7 (55.7–69.6) | 63.8 (54.9–72.7) | ||

| High | 24.6 (21.0– 28.3) | 22.5 (15.9–29.2) | 15.9 (8.4–23.5) | ||

| Other behavioral risk factors | School performance* | Mostly A’s or B’s | 96.0 (93.3– 98.8) | 96.7 (94.8–98.7) | 87.4 (80.1–94.7) |

| Mostly C’s, D’s, and F’s | 4.0 (1.2–6.7) | 3.3 (1.3–5.2) | 12.6 (5.3–19.9) | ||

| Other substance use | No | 94.8 (91.4– 98.2) | 96.0 (93.7–98.2) | 94.8 (92.2–97.4) | |

| Yes | 5.2 (1.8–8.6) | 4.0 (1.8–6.3) | 5.2 (2.6–7.8) | ||

| Alcohol use§ | No | 96.2 (93.3– 99.0) | 96.6 (94.6–98.6) | 95.4 (92.9–98.0) | |

| Yes | 3.8 (1.0–6.6) | 3.4 (1.4–5.4) | 4.6 (2.0–7.1) | ||

| Risk perceptions | Addictiveness of E-cigarettes | Not at all | 57.8 (45.2– 70.4) | 53.8 (44.0–63.5) | 52.6 (43.6–61.6) |

| Any perceived addictiveness | 42.2 (29.6– 54.8) | 46.2 (36.5–56.0) | 47.4 (38.4–56.4) | ||

| E-cigarettes are harmful* | (Range: 1–4) | 3.33 (0.08) | 3.34 (0.07) | 2.98 (0.08) | |

| Social influences and norms | Family influence | No | 89.1 (85.5– 92.7) | 87.4 (81.8–93.0) | 88.5 (83.8–93.2) |

| Yes | 10.9 (7.3–14.5) | 12.6 (7.0–18.2) | 11.5 (6.8–16.2) | ||

| Friend influence* | None | 96.6 (93.9– 99.2) | 88.3 (82.3–94.2) | 70.2 (60.5–79.8) | |

| Any friends | 3.4 (0.8–6.1) | 11.7 (5.8–17.7) | 29.8 (20.2–39.5) | ||

| Social norm: okay to use E-cigarettes* | No | 97.7 (94.8– 100) | 96.8 (94.7–98.9) | 87.0 (80.6–93.4) | |

| Yes | 2.3 (0–5.2) | 3.2 (1.1–5.3) | 13.0 (6.6–19.4) | ||

| Social norm: common to use E-cigarettes* | (Range: 1–5) | 1.29 (0.05) | 1.74 (0.05) | 2.71 (0.09) | |

| Social norm: would date E-cigarette user* | (Range: 1–5) | 1.08 (0.02) | 1.20 (0.05) | 1.32 (0.06) | |

| Individual psychological risk factors | Positive affect* | (Range: 1–5) | 4.22 (0.06) | 3.93 (0.13) | 4.03 (0.05) |

| Emotional problems* | (Range: 1–10) | 1.64 (0.14) | 1.72 (0.19) | 2.31 (0.18) | |

| Sensation seeking scale* | (Range: 1–5) | 2.50 (0.11) | 2.70 (0.10) | 2.91 (0.07) | |

| Outcome | Susceptible to E-cigarettes at 12 months | No | 82.0 (77.9– 86.1) | 78.7 (72.9–84.4) | 77.6 (73.3–81.9) |

| Yes | 18.0 (13.9– 22.1) | 21.3 (15.6–27.1) | 22.4 (18.1–26.7) | ||

| Total population | % (95% Confidence interval) | 43.7 (28.7– 58.8) | 33.5 (21.0–46.0) | 22.8 (13.8–31.7) |

Note: N represents the number of never-users of e-cigarettes who were non-susceptible at baseline. Estimates represent the % (95% confidence interval) for categorical variables and mean (S.E.) for continuous variables. All percentages are weighted to account for the complex survey design.

indicate significant chi-square test or t-test (p < 0.05) for specific variable versus grade level.

Alcohol Use is a subset of Other Substance Use; n = 524 for 6th graders.

Susceptibility to e-cigarettes at 12 months did not vary significantly by grade level: 18.0%, 21.3%, and 22.4% of 6th, 8th, and 10th graders, respectively, who were non-susceptible at baseline became susceptible by 12 months. Of note, the proportion of adolescents with any friends who use e-cigarettes was significantly higher with each increasing grade level (3.4% for 6th graders, 11.7% for 8th graders, and 29.8% for 10th graders), and mean scores for believing “it is common to use e-cigarettes” were also significantly higher with each increasing grade level (1.29 (SE = 0.05) for 6th graders, 1.74 (SE = 0.05) for 8th graders, and 2.71 (SE = 0.09) for 10th graders). Combustible tobacco product (i.e., cigarettes, cigar, and hookah) use was low: < 1% of the analytic sample reported past 30-day use and < 2% reported ever use (data not shown).

4.2. Transition to susceptibility

Across each grade level, different risk factors predicted the transition to susceptibility to e-cigarettes by 12 months (Table 2). In contrast, gender and family SES were not associated with transition to becoming susceptible to e-cigarette use at any grade level. However among 8th graders, Hispanic youth had 3.14 (95% CI: 1.35–7.33) times higher odds of becoming susceptible by 12 months compared to the reference group of White/Other youth (p < 0.01; data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline risk factors predicting the transition from non-susceptible to susceptible at 12 months (n = 1369; N = 228,556).

| |

6th Grade (n = 526) |

8th Grade (n = 478) |

10th Grade (n = 365) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Risk factors | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Other behavioral risk factors | School performance (Ref: Mostly A’s or B’s) | Mostly C’s, D’s, and F’s | 3.20 | 0.75–13.61 | 0.12 | 12.98 | 1.58–106.84 | 0.02 | 2.05 | 0.91–4.61 | 0.08 |

| Other substance use (ref: no) | Yes | 7.81 | 2.66–22.95 | < 0.01 | 3.92 | 1.19–12.93 | 0.03 | 1.43 | 0.51–4.00 | 0.49 | |

| Risk perceptions | Addictiveness of E-cigarettes (Ref: Not at all) | Any perceived addictiveness | 1.48 | 0.67–3.26 | 0.34 | 0.87 | 0.47–1.58 | 0.64 | 1.14 | 0.54–2.44 | 0.73 |

| E-cigarettes are harmfula | (Range: 1–4) | 1.49 | 0.96–2.30 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 0.49–0.95 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 0.76–1.44 | 0.79 | |

| Social influences and norms | Family influence (ref: no) | Yes | 4.72 | 1.09–20.56 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.28–2.36 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.23–1.88 | 0.44 |

| Friend influence (ref: none) | Any | 3.32 | 0.95–11.64 | 0.06 | 3.88 | 0.69–21.92 | 0.13 | 1.25 | 0.55–2.85 | 0.59 | |

| Social norm: okay to use E-cigarettes (Ref: No) | Yes | 0.25 | 0.01–4.54 | 0.35 | 6.69 | 1.24–36.01 | 0.03 | 2.41 | 0.98–5.93 | 0.06 | |

| Social norm: common to use E-cigarettesb | (Range: 1–5) | 0.78 | 0.48–1.27 | 0.32 | 1.42 | 1.14–1.78 | < 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.75–1.28 | 0.87 | |

| Social norm: would date E-cigarette userc | (Range: 1–5) | 0.76 | 0.25–2.27 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.31–0.88 | 0.01 | 1.14 | 0.69–1.87 | 0.61 | |

| Individual psychological risk factors | Positive Affectd | (Range: 1–5) | 0.71 | 0.52–0.95 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 0.46–0.80 | < 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.57–1.43 | 0.67 |

| Emotional Problemse | (Range: 1–10) | 1.14 | 0.90–1.44 | 0.28 | 1.11 | 0.97–1.27 | 0.14 | 1.03 | 0.87–1.22 | 0.77 | |

| Sensation Seeking Scalef | (Range: 1–5) | 1.29 | 0.97–1.71 | 0.08 | 1.45 | 1.06–1.99 | 0.02 | 1.35 | 1.02–1.77 | 0.04 | |

Note: All models are adjusted for gender, ethnicity, and family SES. CI = confidence interval. N represents the number of never-users of e-cigarettes who were non-susceptible at baseline.

Scale ranged from 1 to 4, with 1 being “not at all harmful”; higher score indicates higher perception that e-cigarettes are harmful.

Scale ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being “not at all common”; higher score indicates higher perception that e-cigarettes are common.

Scale ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being “strongly disagree”; higher score indicates higher agreement with dating an e-cigarette user.

Scale ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher positive affect.

Scale ranged from 1 to 10, with higher scores corresponding to more emotional problems.

Scale ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher sensation seeking.

6th Graders.

For 6th graders, those who used other substances at baseline had 7.81 times higher odds of becoming susceptible by 12 months compared to those who did not use other substances (p < 0.01), while those who had a family member who used e-cigarettes at baseline had 4.72 times higher odds of becoming susceptible by 12 months compared to those who did not have family members that used e-cigarettes (p = 0.04). Positive affect was protective against this transition for 6th graders, with each 1 unit increase in positive affect score at baseline corresponding to 0.71 times the odds of becoming susceptible at 12 months (p = 0.02).

8th Graders.

Among 8th graders, poor school performance (OR = 12.98, p = 0.02) and use of other substances (OR = 3.92, p = 0.03) at baseline, were associated with higher odds of transitioning to susceptibility by 12 months. Each unit increase in the risk perception that e-cigarettes are harmful was associated with lower odds of transitioning (OR = 0.69, p = 0.03). Adolescents who agreed “it is okay to use e-cigarettes” had higher odds of becoming susceptible at 12 months (OR = 6.69, p = 0.03), while each one unit increase in score for believing “it is common to use e-cigarettes” corresponded to higher odds of transitioning (OR = 1.42, p < 0.01). In contrast, willingness to date an e-cigarette user is associated with lower odds of transitioning as each one unit increase in agreement with the statement “would date an e-cigarette user” corresponded to lower odds of transitioning (OR = 0.52, p = 0.01). Lower positive affect (OR = 0.61, p < 0.01) and higher sensation seeking scores (OR = 1.45, p = 0.02) at baseline also predicted the transition to susceptibility by 12 months among 8th graders.

10th Graders.

Only one factor significantly predicted the transition to susceptibility for 10th graders. Each one unit increase in sensation seeking score at baseline was associated with 1.35 times higher odds of becoming susceptible to e-cigarettes 12 months in the future (p = 0.04).

5. Discussion

Most studies to date have considered the applicability of the susceptibility construct in predicting future tobacco product use, and in particular cigarette use (Jackson et al., 1998; Jackson & Dickinson, 2004; Pierce et al., 1996; Pierce et al., 2005; Unger et al., 1997), while only a handful of studies have identified risk factors associated with being susceptible to use (e.g., Wilkinson et al., 2008). Less research is available on predictive factors as they relate to the transition from non-susceptible to susceptible status among adolescents (Prokhorov et al., 2002) and none on this transition as it relates to e-cigarette use. Here we assess risk factors associated with the transition to susceptibility to e-cigarettes among youth, using a comprehensive model to assess multiple risk factors in order to account for potential shared variance and to determine which factors are most influential at each grade level (and thus, provide most leverage) for intervention strategies that target e-cigarette use among youth. Many risk factors we identified as associated with the transition are consistent with risk factors previously reported, but not examined by grade level, to increase susceptibility to cigarettes (i.e. Spelman et al., 2009; Wellman et al., 2016), lending support to the overall pattern of results.

6th graders.

Use of e-cigarettes among family members was an important influence on the transition to becoming susceptible among the 6th graders, which is consistent with Abroms, Simons-Morton, Haynie, and Chen (2005)’s findings: higher levels of parental involvement, monitoring, and expectations decreased the likelihood of being an “early tobacco experimenter.” Interventions targeting this age group could also target parents and siblings in order to reduce substance use in the home and increase parental involvement (i.e. knowledge of children’s activities, interests, health habits, free time, and school) to reduce their child’s risk of e-cigarette use.

6th and 8th graders.

Among the 6th and 8th graders use of other substances at baseline, like alcohol or marijuana, was associated with e-cigarette use a year later, underscoring that there may be a sub-group of youth for whom substance use prevention, including that of e-cigarettes, must begin prior to middle school. Positive affect served as a protective factor against the transition to e-cigarette susceptibility among both 6th and 8th graders. The role of positive affect with regards to the transition from non-susceptible to susceptible to e-cigarette use among youth has not been examined to date, but negative affect is a documented risk factor for tobacco use (Stevens, Colwell, Smith, Robinson, & McMillan, 2005) and substance use in general (Hussong, Ennett, Cox, & Haroon, 2017). Given the protective role positive affect played among both 6th and 8th graders, interventions that promote and support positive affect among youth may serve to reduce the transition to susceptibility to e-cigarette use.

8th graders.

Adolescents transitioning from middle to high school–-participants in 8th grade at baseline and 9th grade when susceptibility status was re-assessed–displayed the largest number of risk factors. As such, our results echo the well-documented exponential increase in e-cigarette use that occurs at the onset of high-school (USDHHS, 2016; Jamal et al., 2017). Among middle school students, Hispanic youth report the highest ever use rates of e-cigarettes of all ethnic groups (USDHHS, 2016). Consistent with this finding, we found that Hispanic youth were the only group at increased risk for becoming susceptible to e-cigarettes. Overall, our results underscore the need for intervention efforts targeting behavioral, social, and psychosocial risk factors throughout middle school and through the transition into high school, when the majority of risk factors we examined exert an influence.

The odds of transitioning to susceptibility were almost 13 times higher among those with poor school performance compared to peers with good grades, which is also a known risk factor for other substance use (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). This suggests that targeting interventions to this vulnerable group of students with poor school performance, especially in middle school, may assist in preventing this transition too.

Among those transitioning from 8th to 9th grade beliefs that e-cigarettes “are okay to use” and “are commonly used” increased risk, while willingness to date an e-cigarette user and the belief that “e-cigarettes are harmful to health” were protective, underscoring the important roles that social influence and risk perceptions can play in facilitating the transition. Thus, interventions with tailored messages aimed at altering perceptions and beliefs about e-cigarettes to lessen the impact of social influences and risk perceptions may serve to prevent their progression to susceptibility and will be important for this group.

8th and 10th graders.

Consistent with previous work (Case et al., 2017; Wills, Knight, Williams, Pagano, & Sargent, 2015), higher levels of sensation seeking increased risk among both 8th and 10th graders. This suggests that developing interventions to address modifiable risk factors among high sensation seekers may serve to reduce the number transitioning. Also, sensation seeking was the only risk factor we examined that was associated with the transition to susceptibility between 10th and 11th grade. Hence, either additional research is necessary to identify other risk factors associated with susceptibility among older adolescents, or intervention efforts must start earlier to curb the transition into susceptibility.

5.1. Strengths and limitations

The notable strengths of this study include its complex, longitudinal design and use of weights to generate a representative sample. Further, we employ an e-cigarette susceptibility measure that has been shown to be appropriate for use with our specific population (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016; Bold et al., 2016), and other measures from valid and reliable sources that have been thoroughly tested via cognitive interviewing (Delk, Harrell, Fakhouri, Muir, & Perry, 2017). Given the longitudinal study design, we avoid temporal ambiguity in our assessment of adolescents’ transition from non-susceptible to susceptible stages of e-cigarette use. We are also able to examine age groups separately, allowing for a more developmentally relevant picture of adolescent transitions with real implications for intervention and prevention efforts.

Among our limitations is the possibility that adolescents could transition in and out of susceptibility statuses, yet we are unable to determine after their initial transition if they remain susceptible or become non-susceptible again, or how those with fluctuating statuses differ from those who do not fluctuate. Likewise, it is possible for some risk factors to change across study waves (e.g. on average, every six months), and as we only assessed risk factors at baseline, it is unclear whether changes in these factors may also be relevant to the transition to susceptibility. Future studies should consider the fluctuation in susceptibility stage and/or predictive factors in examining the association between susceptibility transitions and e-cigarette use.

In addition, due to limited sample size, we were unable to examine the influence of currently using other combustible tobacco products on becoming susceptible to e-cigarettes, which others have found to exert a strong influence (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016). Finally, we examined the influence of emotional problems and positive affect on e-cigarette use rather than negative affect, which is typically assessed in tobacco research; more research will be needed to understand the influence of negative affect on e-cigarette use.

6. Conclusions

Our findings echo those of previous research on cigarettes and suggest that behavioral factors, social influences, and risk perceptions play an important role in predicting the transition to susceptibility among e-cigarette naïve adolescents. Our results also emphasize the relevance of affective states, such as positive affect and sensation seeking, in predicting the transition to susceptibility. Tailoring intervention materials, by grade level, to address these factors will provide useful targets for intervention in adolescent populations. These results vary depending on the age of the adolescent group, suggesting that intervention strategies should use age appropriate targeting to maximize the effectiveness of intervention efforts in preventing the transition to susceptibility and across e-cigarette use trajectories. Future research could use statistical techniques such as structural equation modeling to determine whether any of the risk factors examined serve as mediators and/or moderators of the transition to susceptibility among adolescents to further hone preventive interventions.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Incident susceptibility to e-cigarettes at 12 months did not vary by grade (6th, 8th, or 10th); risk factor profiles did vary

Family influence andr substance use increased risk e-cigarette susceptibility for grade 6; positive affect was protective

Social and normative influences for becoming susceptible to e-cigarettes were important during the transition to high school

Only higher sensation seeking increased risk of becoming susceptible to e-cigarettes among the 10th graders

Tailoring intervention efforts to developmental stage can maximize prevention against e-cigarette susceptibility transitions

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

This research was supported by grant number [1 P50 CA180906-01] from the National Cancer Institute and the Federal Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Food and Drug Administration or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Declarations of interest

None.

References

- Abroms L, Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, & Chen R (2005). Psychosocial predictors of smoking trajectories during middle and high school. Addiction, 100(6), 852–861. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett D,&E (1996). The three stages of adolescence. The High School Journal, 79(4), 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Urman R, Chou CP, … McConnell R (2016). The E-cigarette social environment, E-cigarette use, and susceptibility to cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(1), 75–80. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, & Krishnan-Sarin S (2016). E-cigarette susceptibility as a predictor of youth initiation of e-cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 10.1093/ntr/ntw393. ntw393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Case KR, Harrell MB, Pérez A, Loukas A, Wilkinson AV, Springer AE, … Perry CL (2017). The relationships between sensation seeking and a spectrum of e-cigarette use behaviors: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses specific to Texas adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 151–157. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delk J, Harrell MB, Fakhouri THI, Muir KA, & Perry CL (2017). Implementation of a computerized tablet-survey in an adolescent large-scale, school-based study. The Journal of School Health, 87(7), 506–512. 10.1111/josh.12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EHCAP (2014). Scoring the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire for age 4–17.

- Gore S, Aseltine RH, & Colton ME (1992). Social structure, life stress and depressive symptoms in a high school-aged population. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33(2), 97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Mullin Jones M, Rosenblum C, Chang CC, … de Moor C (2003). Predictors of susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking: A longitudinal study in a triethnic sample of adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 5(4), 493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Ennett ST, Cox MJ, & Haroon M (2017). A systematic review of the unique prospective association of negative affect symptoms and adolescent substance use controlling for externalizing symptoms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 31(2), 137–147. 10.1037/adb0000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Lambert E, Carusi C, … Compton WM (2017). Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco Control, 26(4), 371–378. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, & Dickinson D (2004). Cigarette consumption during childhood and persistence of smoking through adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(11), 1050–1056. 10.1001/archpedi.158.11.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Dickinson D, Messer L, & Robertson SB (1998). A longitudinal study predicting patterns of cigarette smoking in late childhood. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 25(4), 436–447. 10.1177/109019819802500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu SS, Cullen KA, Apelberg BJ, Homa DM, & King BA (2017). Tobacco use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(23), 597–603. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6623a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Stone MD, Andrabi N, Barrington-Trimis J, Strong DR, Sussman S, & Audrain-McGovern J (2016). Association of e-cigarette vaping and progression to heavier patterns of cigarette smoking. JAMA, 316(18), 1918 10.1001/jama.2016.14649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, & van den Berg F (2003). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 12(1), 1–8. 10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez A, Harrell MB, Malkani RI, Jackson CD, Delk J, Allotey PA, … Perry CL (2017). Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance System’s design. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 3(2), 151–167. 10.18001/TRS.3.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, & Merritt RK (1996). Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 15(5), 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Distefan JM, Kaplan RM, & Gilpin EA (2005). The role of curiosity in smoking initiation. Addictive Behaviors, 30(4), 685–696. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, de Moor CA, Hudmon KS, Hu S, Kelder SH, & Gritz ER (2002). Predicting initiation of smoking in adolescents: Evidence for integrating the stages of change and susceptibility to smoking constructs. Addictive Behaviors, 27(5), 697–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Cuéllar I, & Roberts RE (2000). Ethnocultural variables and attitudes toward cultural socialization of children. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 79–89. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Koskelainen M, Niemelä S, Rihko M, Ristkari T, & Lindroos J (2012). Changes in adolescents mental health and use of alcohol and tobacco: A 10-year time-trend study of Finnish adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 21(12), 665–671. 10.1007/s00787-012-0303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spelman AR, Spitz MR, Kelder SH, Prokhorov AV, Bondy ML, Frankowski RF, & Wilkinson AV (2009). Cognitive susceptibility to smoking: Two paths to experimenting among Mexican origin youth. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 18(12), 3459–3467. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer AE, Selwyn BJ, & Kelder SH (2006). A descriptive study of youth risk behavior in urban and rural secondary school students in El Salvador. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 6, 3 10.1186/1472-698X-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson MT, Hoyle RH, Palmgreen P, & Slater MD (2003). Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 72(3), 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens SL, Colwell B, Smith DW, Robinson J, & McMillan C (2005). An exploration of self-reported negative affect by adolescents as a reason for smoking: Implications for tobacco prevention and intervention programs. Preventive Medicine, 41(2), 589–596. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Hartman SJ, Nodora J, Messer K, James L, White M, … Pierce J (2015). Predictive Validity of the Expanded Susceptibility to Smoke Index. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 17(7), 862–869. 10.1093/ntr/ntu254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas SL, & Pederson LL (1998). Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: A critical review of the literature. Tobacco Control, 7(4), 409–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the surgeon general Atlanta, GA: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: A report of the surgeon general Atlanta, GA: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Johnson CA, Stoddard JL, Nezami E, & Chou CP (1997). Identification of adolescents at risk for smoking initiation: Validation of a measure of susceptibility. Addictive Behaviors, 22(1), 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman RJ, Dugas EN, Dutczak H, O’Loughlin EK, Datta GD, Lauzon B, & O’Loughlin J (2016). Predictors of the onset of cigarette smoking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(5), 767–778. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson AV, Waters AJ, Vasudevan V, Bondy ML, Prokhorov AV, & Spitz MR (2008). Correlates of susceptibility to smoking among Mexican origin youth residing in Houston, Texas: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 10.1186/1471-2458-8-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, & Sargent JD (2015). Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics, 135(1), e43–e51. 10.1542/peds.2014-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]