Abstract

The impact of influenza virus infection is felt each year on a global scale when approximately 5–10% of adults and 20–30% of children globally are infected. While vaccination is the primary strategy for influenza prevention, there are a number of likely scenarios for which vaccination is inadequate, making the development of effective antiviral agents of utmost importance. Anti-influenza treatments with innovative mechanisms of action are critical in the face of emerging viral resistance to the existing drugs. These new antiviral agents are urgently needed to address future epidemic (or pandemic) influenza and are critical for the immune-compromised cohort who cannot be vaccinated. We have previously shown that lipid tagged peptides derived from the C-terminal region of influenza hemagglutinin (HA) were effective influenza fusion inhibitors. In this study, we modified the influenza fusion inhibitors by adding a cell penetrating peptide sequence to promote intracellular targeting. These fusion-inhibiting peptides self-assemble into ç15–30 nm nanoparticles (NPs), target relevant infectious tissues in vivo, and reduce viral infectivity upon interaction with the cell membrane. Overall, our data show that the CPP and the lipid moiety are both required for efficient biodistribution, fusion inhibition, and efficacy in vivo.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus (influenza) infection is a pervasive global issue, with more than 1 billion people infected annually and morbidity rates between 290,000 and 650,000 people for a given flu season.1,2 While prevention is mediated primarily by seasonally reformulated vaccines, the propensity of influenza to mutate and undergo antigenic shift and drift greatly undermines efforts at prevention. During the 2014–2015 season, in the Northern hemisphere, the vaccine was mismatched with the strain that emerged, and vaccine efficacy was low.3,4 While the overall efficacy for a well-matched vaccine has typically ranged between 50 and 70%, CDC reports from the 2017–2018 season reported 25% efficacy rates for the H3N2 vaccine strain and as low as 10% in other countries.5,6 Additionally, recent studies have revealed that the primary method of vaccine production in chicken eggs can result in a less effective vaccine following prorogation, which further complicates vaccination efforts.7 As a result, antivirals for prophylaxis and treatment are important for combatting global influenza infection, especially in years of high disease burden. Of the currently approved antivirals, most target influenza neuraminidase (NA), namely oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir.8,9 In contrast, hemagglutinin (HA)-targeting antivirals are currently unavailable. As HA mediates virus attachment and entry into target cells, it is an attractive target for halting infection in its earliest phase.

HA is synthesized as an HA0 precursor that is cleaved within the cell to yield the prefusion HA complex comprising three C-terminal HA2 subunits associated with three N-terminal HA1 subunits. HA1 contains the sialic acid binding domain and mediates attachment to the target cells. The HA2 structure is kinetically trapped in a metastable conformation, primed for fusion activation by low pH in the endosome. After pH priming, prefusion HA2 undergoes a structural transition, driven by formation of an energetically stable trimer of α-helical hairpins in HA2 that promote virus-cell membrane fusion.10–12 Much of what is known about the structure—function relationships of HA has emerged from structural studies,13,14 showing that the soluble core of the postfusion trimer-of-hairpins is formed by antiparallel association of two conserved heptad-repeat (HR) regions in the HA2 ectodomain. The first repeat (HRN) is adjacent to the N-terminal fusion peptide, which is exposed and inserted into the target cell membrane in the fusion process, while the second short repeat (HRC) is followed by a C-terminal “leash”, which anchors the HA to the viral membrane. The two HR domains form a short, membrane distal six-helix bundle (6HB), and the extended chain (leash) packs into the grooves of the membrane proximal trimeric HRN structure. The formation of this hybrid (6HB and leash in the groove) structure is required for fusion.15

We showed that peptides derived from the membrane proximal domain (the “leash”), when conjugated to cholesterol (Chol), block influenza HA mediated fusion in vitro.16 The HA2-derived Chol-conjugated peptide that we designed blocks fusion of influenza virus with liposomes as well as infection of live cells.16 Since influenza viruses are initially endocytosed and the conformational changes in HA are triggered by the acidic pH of the endosome, it was thought that influenza would escape the inhibitory activity of fusion inhibitory peptides. However, the lipid-conjugated peptides derived from influenza HA inhibited infection by influenza, suggesting that the lipidconjugation-based strategy enables the use of fusion-inhibitory peptides for viruses that fuse in the cell interior.16 To further improve the intracellular localization of the peptide, we added a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) sequence17–19 derived from HIV-1 TAT.20 We show here that TAT-derived CPP sequence and the lipid moiety enhance the in vitro and in vivo efficacy via efficient intracellular localization and fusion inhibition.

RESULTS

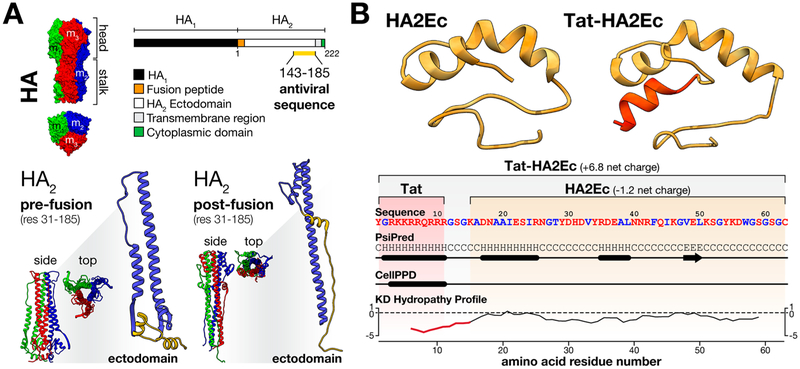

Peptides derived from the influenza A HA2 ectodomain (X-31, H3 clade, residues 155–185) can capture a fusion intermediate state of HA, blocking the conformational transitions involved in influenza pH-triggered viral fusion (Figure 1, A).16 In the present study, we designed an elongated peptide sequence covering a larger portion of the HA2 ectodomain for increased sequence complementarity (HA2Ec; Figure 1, B). The additional 12 amino acid residues located at the N-terminus (residues 143–154) include a small α-helical secondary structure motif involved in HA2 helix–helix interactions, which contribute as major stabilizing forces in HA prefusion conformations. As a major improvement to this design, we have generated a peptide sequence containing a cell penetrating amino acid domain derived from the HIV-1 TAT nuclear translocating protein (Tat peptide),21 inserted into the N-terminal of the HA2Ec sequence via a glycine-serine linker (Tat-HA2Ec; Figure 1, B). Since influenza fusion occurs within endosomal compartments, Tat is expected to improve targeting by promoting peptide cell translocation, potentially permitting peptide to reach endocytosed influenza virions.

Figure 1.

Influenza virus HA2-derived fusion inhibitor peptides design and structural features. (A) Influenza HA glycoprotein was used as a template for design of antiviral fusion inhibitory peptides. A 43 amino acid residue sequence derived from the influenza HA2 ectodomain (X-31, H3 clade, res 143–185), which is involved in HA structural reorganization upon pH triggering, was selected for further development. This sequence is highlighted (in yellow) in a schematic representation of the HA structure and in the tridimensional representations of the monomeric HA2 ectodomain. Complete influenza HA (PDB: 1QU1), prefusion HA2 (PDB: 1QU1), and postfusion HA2 (PDB: 2HMG) protein trimer structures are included in top and side views. (B) Homology-based prediction of the HA2Ec and Tat-HA2Ec peptides molecular structure, obtained through the I-TASSER online server.24 Both peptides were developed from the described HA2-derived sequence. The Tat domain is evidenced in red, in the respective peptide representation. A color-coded peptide sequence (red–polar, blue–hydrophobic), PSIPRED sequence-based secondary structure prediction (C – random coil, H − α-helix, E − β-sheet),25 CellPPD cell-penetrating peptide domain prediction,26 and Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy profile are included to highlight and compare peptides structural features. In all cases, tridimensional molecular structures were prepared using the UCSF Chimera software.27

HA2Ec and Tat-HA2Ec peptides were chemically engineered to incorporate a flexible polyethylene glycol (PEG) linker and a Chol or tocopherol (Toc) moiety, conjugated through the C-terminal cysteine residue (Table 1). These modifications adhere to a general strategy for antiviral fusion inhibitor optimization,22 recently linked to properties of self-assembly and lipid membrane targeting that have been shown to enhance in vivo biodistribution and efficacy.23 Chol and Toc-driven cell membrane partition and anchoring to membranes may facilitate peptide cell internalization in the presence of Tat-mediated translocation mechanisms. In this study, we investigate the fusion inhibitory properties of the peptides and their mechanism of action. Peptide leads are then selected for in vivo antiviral therapeutic and prophylactic efficacy studies in a cotton rat model of influenza infection. Furthermore, we assess peptide properties such as solution stability, lipid membrane interaction, and tissue biodistribution, to correlate the design features of the peptides with their biological and antiviral activities.

Table 1.

Chemical Composition of the Influenza-Specific Peptides Studied in the Present Work

| peptide | chemical compositiona |

|---|---|

| HA2Ecl | Ac-KADNAAIESIRNGTYDHDVYRDEALNNRFQIKGVELKSGYKDWGSGSGC(CAM)-NH2 |

| HA2Ec2 | Ac-KADNAAIESIRNGTYDHDVYRDEALNNRFQIKGVELKSGYKDWGSGSGC(PEG4-Chol)-NH2 |

| HA2Ec3 | Ac-KADNAAIESIRNGTYDHDVYRDEALNNRFQIKGVELKSGYKDWGSGSGC(PEG4-Toc)-NH2 |

| Tat-HA2Ecl | Ac-YGRKKRRQRRRGSGKADNAAIESIRNGTYDHDVYRDEALNNRFQIKGVELKSGYKDWGSGSGC(CAM)-NH2 |

| Tat-HA2Ec2 | Ac-YGRKKRRQRRRGSGKADNAAIESIRNGTYDHDVYRDEALNNRFQIKGVELKSGYKDWGSGSGC(PEG4-Chol)-NH2 |

| Tat-HA2Ec3 | Ac-YGRKKRRQRRRGSGKADNAAIESIRNGTYDHDVYRDEALNNRFQIKGVELKSGYKDWGSGSGC(PEG4-Toc)-NH2 |

Amino acid residues are represented in single letter code (Ac – acetylated N-terminus; NH2 – amidated C-terminus; PEG – polyethylene glycol; CAM – cysteine carbamidomethylation).

Tat Conjugation Improves the Fusion Inhibitor Properties of Influenza HA2-Derived Peptides.

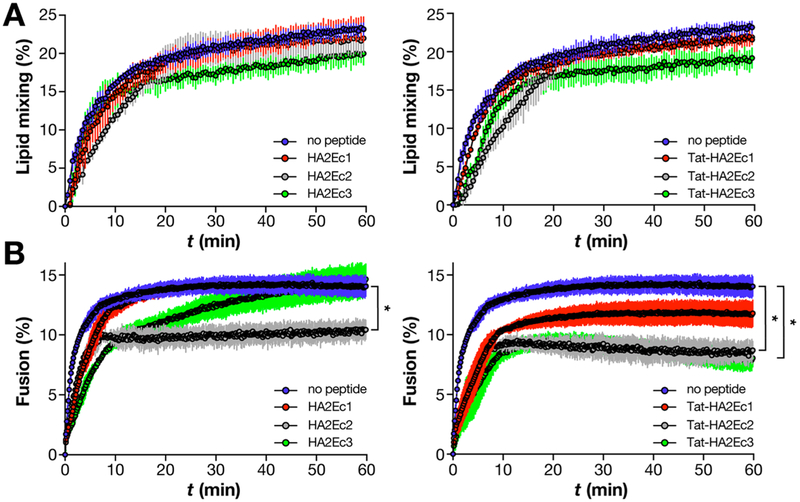

In order to screen the peptides’ fusion inhibitory efficacy and compare the impacts of the various chemical modifications made to the HA2Ec and Tat-HA2Ec sequences, we used an influenza lipid mixing and fusion kinetics assay. The methodology takes advantage of the pH-sensitive influenza fusion machinery to trigger HA fusogenic conformations that can insert into target model membranes (i.e. liposomes). Through the use of liposomes labeled with membrane and lumen fluorescent probes, we quantify the subsequent lipid mixing and fusion events between the viral envelope and liposome membranes via time-resolved fluorescence dequenching and energy transfer (FRET), respectively. DOPC, an unsaturated phospholipid, was used as single component in these systems.

In the absence of peptide, both lipid mixing and fusion kinetics follow a characteristic hyperbolic profile, saturating after 10–20 min (Figure 2). The low dynamic range observed in both cases can be attributed to the incremental increase in both lipid surface area and internal volume, upon HA-mediated membrane mixing and fusion. When preincubated with liposomes, HA2Ec and Tat-HA2Ec1 peptides exerted little effect on influenza lipid mixing kinetics when compared to the control, with the exception of Toc-conjugated HA2Ec3 and Tat-HA2Ec3 (Figure 2, A). In contrast, fusion was inhibited by both HA2Ec and Tat-HA2Ec peptides, the latter group having a more significant inhibitory effect (Figure 2, B). Of all the studied peptides, the unconjugated HA2Ec1 peptide was the weakest inhibitor of influenza fusion. Both HA2Ec2 and HA2Ec3 inhibited influenza fusion more significantly than HA2Ec1, indicating the role of Chol and Toc chemical conjugation, respectively. Tat-HA2Ec1 was significantly more effective when compared to HA2Ec1 (lower maximum fusion), which suggests an improvement associated with Tat conjugation. Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 were the most potent inhibitors, displaying the strongest inhibitory effect on viral fusion of the inhibitors studied. The observed antiviral action of these peptides was sequence-dependent, as confirmed by controls performed with Tat-conjugated human parainfluenza 3 (hPIV3)-specific VG peptides28 (Table S1). Additionally, this suggests that Tat-conjugation by itself is unrelated to influenza fusion inhibition. Overall the data suggest that our combined conjugation strategy, including both a N-terminal Tat motif and a C-terminal lipophilic domain, improved the HA2Ec sequence’s intrinsic fusion inhibitory properties. Tat-HA2Ec peptides will be further studied in the following sections.

Figure 2.

Tat-conjugation enhances the inhibition of influenza fusion, but not lipid mixing, with liposomes by HA2-derived fusion inhibitor peptides. Kinetics profiles of influenza A X-31 H3N2 (0.1 mg/mL of total viral protein) pH-triggered lipid mixing (A) and fusion (B) with DOPC liposomes (0.2 mg/mL), in the presence of HA2Ec1–3 (left) or Tat-HA2Ec1–3 (right) fusion inhibitor peptides (10 μM) or in the absence of peptide. Lipid mixing and fusion between viruses and liposomes was quantified through NBD-PE/Rho-PE FRET in membranes and encapsulated SRho-B fluorescence dequenching, respectively, using eqs 1 and 2. Fluorescence data were collected for a period of 60 min, after triggering at pH 5. Statistical significance of the differences between the influenza virus fusion after 60 min, in the absence or presence of each peptide (*, P ≤ 0.05) was analyzed using Student’s t-test. Results are the average of three independent replicates.

The Lipophilic Moieties Drive Tat-HA2Ec Peptides Assembly into Stable Nanoparticles.

The amphipathic nature of Chol- and Toc-conjugated peptides is a driving force for aggregation and a determinant of aggregate stability.29 Moreover, through addition of a N-terminal highly hydrophilic Tat motif, the amphipathic nature of peptides is greatly increased. For this reason, we questioned if Tat-HA2Ec peptides’ behavior in solution reflects the amphipathic chemical structure, leading to aggregation in solution. Using an 1-anilino-8-naphtalene-sulphonate (ANS) fluorescence-based approach,30 we obtained strong evidence that Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 peptides form hydrophobic pockets in solution, typical of lipid-derivatized peptides (Figure S2). Unconjugated Tat-HA2Ec1 did not aggregate in solution, as shown by ANS fluorescence emission (Figure S2). We further evaluated the size and stability (polydispersity) of aggregates generated from Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 self-assembly using dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis (Figure 3). Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 have similar size distribution profiles with particle number-averaged hydrodynamic diameter (DH) mode between 12 and 14 nm. These values are in agreement with the respective intensity-averaged DH mode values between 21 and 24 nm, which lie within the detection limits of the instrument. Peptide nanoparticles (NPs) size distribution obtained after 3 h incubation overlapped with the data obtained at the beginning of the experiment. Time-resolved polydispersity index (PDI) profiles, used as a measure of stability in solution, did not exceed 0.55 for both Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 (Figure 3, insets). Both NP size and polydispersity results suggest significant structural homogeneity, which is maintained for a 3 h period. The small particle size suggests highly ordered NP packing, which might be influenced by secondary structure features. These observations were valid for both Chol- and Toc-conjugated peptides.

Figure 3.

Chol- and Toc-conjugated Tat-HA2Ec peptides self-assemble into stable NPs. DLS number-averaged size distribution histograms of Tat-HA2Ec2 (A) and Tat-HA2Ec3 (B) NPs (10 μM), measured immediately after sample preparation and after 3 h. Time-resolved profiles of NP PDI, measured over a 3 h period (ç4 min intervals) after sample preparation, are included for each peptide (insets). Results represent one of three independent replicates.

Tat-HA2Ec Peptide NPs Combine Stability in Solution with Efficient Disassembly and Insertion into Lipid Membranes.

Conjugation with lipophilic tags also drives peptide partition toward lipid membranes, namely cell membranes. NPs disassembly at the membrane level and peptide insertion into membranes are determinants of in vivo efficacy.23,31 To understand whether Tat-HA2Ec NPs interact with lipid membranes, despite their stability in solution, we assessed peptide disassembly and partition toward liposomes, as well as localization in the lipid bilayer. Peptide Trp intrinsic fluorescence emission, which is sensitive to the NP, aqueous, and lipid membrane environments, was used to probe peptides interactions. POPC:Chol (2:1) liposomes were used to mimic the phospholipid and Chol composition of relevant biological membranes. Tat-HA2Ec1 was used as a control in the experiments.

Since Trp is located close to the peptide C-terminus, and respective lipophilic tag, it experiences variations in the hydrophobicity of the surrounding microenvironment, within the NP structure. Trp fluorescence emission is sensitive to such variations and thus functions as a reporter of the Tat-HA2Ec peptide NPs internal accessibility and disassembly. Using acrylamide as a fluorescence quencher, we monitored Tat-HA2Ec1–3 Trp emission quenching in aqueous solution and in the presence of liposomes (Figure 4, A–C). Tat-HA2Ec1 Stern–Volmer emission quenching plots were linear both in aqueous solution and in the presence of liposomes. Quenching efficiency was similar in both cases, as reported by the respective KSV values (Table S2). This observation suggests that Trp residues are fully accessible, independent of their insertion in liposomes. In contrast, Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 fluorescence emission quenching profiles displayed a negative curvature relative to the typical linear Stern–Volmer relationship when in aqueous solution (Figure 4, B and C). This suggests that Trp is only partially accessible within both NP structures. The accessible fluorophore fraction (fb) was 0.70 ± 0.05 and 0.73 ± 0.09, respectively, for each peptide. In the presence of liposomes, the Stern–Volmer profiles displayed a linear behavior, similar to that of Tat-HA2Ec1. Upon contact with lipid membranes, the fluorophore seems to be exposed to acrylamide through disassembly of NPs.

Figure 4.

Tat-HA2Ec NPs disassemble and partition into lipid membranes. (A-C) Tat-HA2Ec Trp accessibility in aqueous solution and in the presence of POPC:Chol (2:1) LUVs, evaluated by steady-state fluorescence emission quenching. Stern–Volmer plots of Tat-HA2Ec1 (A), Tat-HA2Ec2 (B), and Tat-HA2Ec3 (C) NP (5 μM) Trp quenching upon titration with acrylamide (0–60 mM). Lines correspond to the best fit of eqs 3 (linear regimes) or 4 (nonlinear regimes) to the experimental data. Results are the average of three independent replicates. (D) Partition of Tat-HA2Ec peptides toward POPC:Chol (2:1) membranes. Partition profiles of Tat-HA2Ec peptides (5 μM) followed by Trp fluorescence emission at increasing lipid concentrations (0–5 mM). Lines correspond to the best fit of eqs 5 (Tat-HA2Ec1) and 6 (Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3). Results represent one of three independent replicates. (E) In-depth POPC:Chol (2:1) membrane localization of Tat-HA2Ec1 and Tat-HA2Ec2 peptides. Lipid bilayer penetration depth histogram of peptide Trp, estimated through differential fluorescence emission quenching with lipophilic 5- and 16-NS (0–665 mM). Stern–Volmer fluorescence quenching profiles are included in Figure S3. Distribution frequency was predicted based on knowledge of quencher in-depth membrane distributions.33 Results represent one of three independent replicates.

To further assess NP-membrane interactions, we quantified the extent of peptide partition toward liposomal membranes (Figure 4, D). Peptide Trp emission variations (positive or negative) in the presence of liposomes show partition between aqueous solution and lipid membranes. Tat-HA2Ec1 Trp fluorescence emission decreased in hyperbolic fashion at increasing lipid concentrations, indicative of peptide partition. Under the same conditions, Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 Trp emission experienced a nonsigmoidal behavior, previously associated with membrane saturation (as a result of partition) and fluorophore self-quenching.32 Trp fluorescence emission intensity variations were not followed by concomitant intensity maxima wavelength shifts (data not shown). Partition constants (Kp’s), a quantitative measure of peptide-membrane interactions, were 3.99 × 103, 2.73 × 103, and 2.79 × 103, for Tat-HA2Ec1, Tat-HA2Ec2, and Tat-HA2Ec3, respectively (Table S2). Our results suggest that the Tat-HA2Ec sequence may play a role in initial NP-membrane interactions, concentrating the peptide in lipid membranes. Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 Trp self-quenching behavior suggests NP reorganization within the lipid environment.

As a consequence of peptide partition toward lipid membranes, we hypothesized that bilayer penetration depth is relevant for the mode of action of the peptides. Using an in-depth membrane localization approach based on differential Trp fluorescence emission quenching, we probed Tat-HA2Ec peptides’ bilayer penetration. Lipophilic doxyl stearic acid probes 5-NS and 16-NS were used as selective quenchers at the lipid bilayer surface and center, respectively. Unconjugated Tat-HA2Ec1 was not quenched by 16-NS and only partially quenched by 5-NS (Figure S3). This observation suggests that Tat-HA2Ec1 adsorbs to the lipid–water interface. Conjugated peptides Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 Trp residues were quenched by both 5-NS and 16-NS quenchers, as evidenced by the respective Stern–Volmer Trp quenching profiles (Figure S3). The membrane in-depth location distributions, estimated through Brownian dynamics simulations,33 predict a shallow location of Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 Trp near the bilayer surface (Figure 4, E). Moderate bilayer penetration of the Trp residue is compatible with Chol and Toc insertion and peptide backbone exposure and flexibility, required for efficient HA target recognition and binding.

Intranasal Administration to Cotton Rats Leads to Bioavailability and Efficacy of Tat-HA2Ec Peptides in Vivo.

To evaluate the safety of Tat-HA2Ec peptides for in vivo applications, we assessed peptide cytotoxicity in an ex vivo model of human airway mucosa. This model tissue consists of normal, human-derived nasal and tracheal/bronchial epithelial cells that have been cultured to form a pseudostratified, highly differentiated model that closely resembles the human epithelial airway (HAE) tissue of the respiratory tract. HAE cultures have been successfully used to characterize fusion inhibitory peptides.23,31,34 The cell viability assay – based on 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) metabolic conversion in live cells to (E,Z)-5-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-1,3-diphenylformazan (formazan)35,36 – shows that peptides were nontoxic at efficacious concentrations (i.e., 10 μM), even when incubated for 24 h. This further supports the utility of Tat-HA2Ec peptides in vivo.

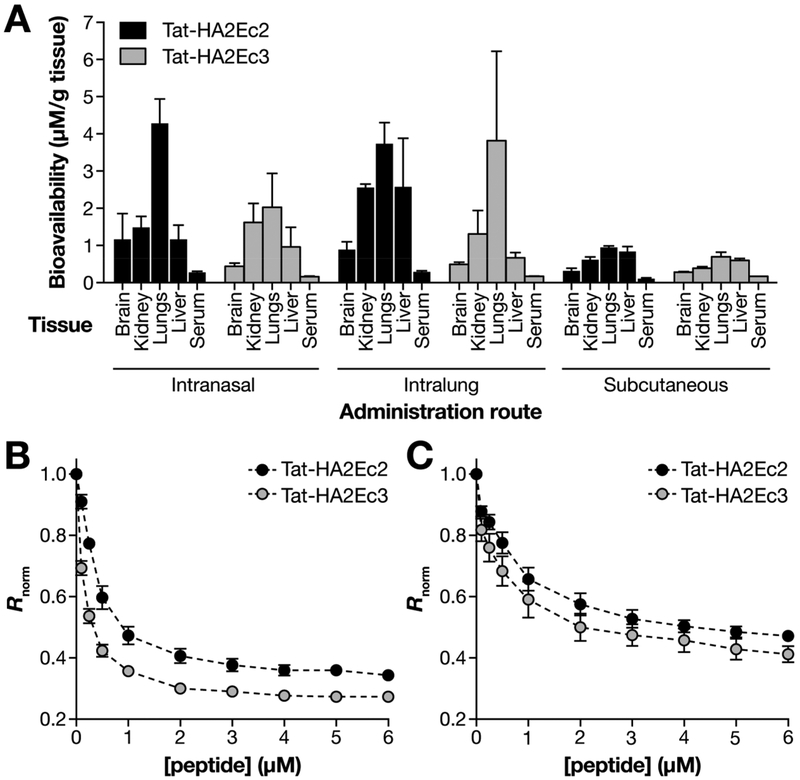

We and several others have shown that intranasal inoculation in small animals results in efficient lung delivery and that, by varying the volume of intranasal inoculation, administration can be limited to the nose (e.g., using 10 μL per naris) or directly to the lung (e.g., using 50 μL per naris).31,37–40 For the in vivo biodistribution experiment shown here, cotton rats were treated with either 10 μL (this volume stays in the nose; intranasal delivery) or 50 μL (this volume is inhaled into the lung; intralung delivery) per naris. Subcutaneous injections were also evaluated. We performed an ELISA based semiquantitative analysis to evaluate the peptides’ biodistribution 8 h postinoculation. Figure 5A shows that both intranasal and intralung delivery result in the highest retention levels of the Tat-HA2Ec2 in the lungs. Tat-HA2Ec3 is mainly localized in the lung tissue after intralung delivery. As previously shown for measles derived peptides,23 intralung delivery of Chol conjugated peptides results in systemic delivery, while the Toc conjugated peptides remain localized to the inoculation site. Subcutaneous delivery resulted in delivery to several organs, including the lungs, but at lower levels. Overall, peptide concentration in serum is low compared to the concentration detected in other tissues. We hypothesize that the low serum concentration may be due to the peptides’ interaction with erythrocytes (RBC) (Figure 5, B) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (Figure 5, C).

Figure 5.

Tat-HA2Ec peptides biodistribution in vivo. (A) Bioavailability of TAT-HA2Ec peptide NPs in cotton rats, at 8 h postdelivery (3 animals per group). Peptides were administered either intranasally (10 μL and 50 μL per naris) or subcutaneously (200 μL). (B and C) Interaction of Tat-HA2Ec peptides with di-8-ANEPPS-labeled RBC (B) and PBMCs (C). Ratiometric analysis of di-8-ANEPPS (10 μM) fluorescence excitation spectrum shifts within eyrthrocytes and PBMCs cell membranes, in the presence of increasing peptide concentrations (0–6 μM). Rnorm values correspond to the ratio between the di-8-ANEPPS excitation intensity at 455 and 525 nm [Iexc(455)/Iexc(525)], calculated for each peptide concentration and normalized to the control value in the absence of peptide. Results are the average of three independent replicates.

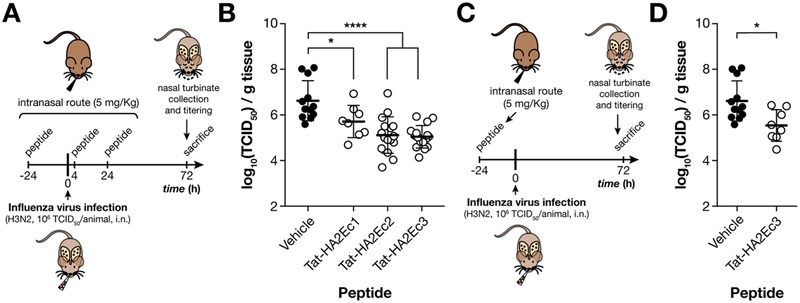

Based on the biodistribution data and the absence of toxicity in HAE, we assessed the in vivo efficacy following intranasal delivery (Figure 6). Animals were treated with the indicated peptides (intranasal, 10 μL per naris) or mock treated. Figure 6 A and C are schematic representations of the combined prophylactic-therapeutic and prophylactic regimens. The animals were treated with three doses (5 mg/kg each) at 24 h before infection, 4 h postinfection, and 24 h postinfection (Figure 6, A and B). One single inoculation 24 h before infection was given to assess prophylaxis (Figure 6, C and D). The animals were infected with 106 TCID50 of influenza A/Wuhan/359/95(H3N2). Three days after infection, the virus from nose homogenates was titered. Both Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 decreased the viral titers (Figure 6, B). Even a single inoculation with the Tat-HA2Ec3 24 h before infection was sufficient to significantly decrease viral titers (Figure 6, D).

Figure 6.

Intranasal administration of Tat-HA2Ec peptide NPs protects cotton rats from influenza infection. Timeline for cotton rat infection with influenza A/Wuhan/359/95 H3N2 (106 TCID50/animal) and either combined prophylactic-therapeutic (A) or prophylactic (C) administration of Tat-HA2Ec fusion inhibitor peptide NPs (5 mg/kg). Both viruses (100 μL) and peptides (20 μL) were administered intranasally. Control animals were treated with vehicle. Nasal turbinate viral titers of infected cotton rats treated with vehicle or Tat-HA2Ec NPs under prophylactic-therapeutic (B) or prophylactic (D) administration regimens. The limit of viral detection was 102 TCID50/g of tissue. Cotton rat treatment groups were composed of 4 animals; experimental conditions were duplicated in at least 2 independent treatment groups. Statistical significance of the differences between the peptide treated and untreated groups (*, P ≤ 0.05; ****, P ≤ 0.0001) was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. i.n. – intranasal.

Tat Promotes Lipid-Conjugated Inhibitor Peptide NP Cellular Internalization.

Based on the observation that both Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 decreased the influenza viral titers in cotton rats (Figure 6), we hypothesized that these peptides undergo cellular internalization, while the HA2Ec2 and HA2Ec3 (despite the lipid moiety) do not. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the cellular localization of the HA2-derived peptides using confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure 7).41 For the experiment shown in Figure 7, cells were incubated for 60 min at 1.5 μM peptide concentration. The intense green spots inside the cells indicate intracellular localization of Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3. This finding was further confirmed through sequential micrographs taken at different z-axis positions, orthogonal to the observation plane (Videos S1–S4). The untagged peptide (HA2Ec1) does not interact with the cells, as expected. The HA2Ec2 (without Tat) remains mostly localized on the cell membrane, with minimal cellular internalization. Only the peptides with both the Tat CPP sequence and the lipophilic moiety are delivered intracellularly (Figure 7, Videos S1–S4), indicating that the differences observed in vivo for both groups of peptides (Figure 6, B) are correlated with the difference in peptide availability. These findings support our hypothesis that both features promote HA2-derived peptides effectiveness in vivo.

Figure 7.

Localization of HA2Ec and Tat-HA2Ec fusion inhibitor peptides in live cells. Confocal fluorescence micrographs of HEK293T cell cultures treated with HA2Ec1, HA2Ec2, Tat-HA2Ec2, or Tat-HA2Ec3 peptides (10 μM) for 60 min, at 37 °C. Peptides and cell nuclei were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and DAPI (blue), respectively. The merge image of the two immunostainings is presented. Results correspond to one of three independent replicates. Supplemental videos compiling sequential z-axis micrographs, orthogonal to the observation plane, taken from cell cultures treated with each peptide are shown in the Supporting Information (Videos S1–S4).

DISCUSSION

Targeting pH-sensitive virus fusion in endosomal compartments is a challenge for newly developed fusion inhibitors.42 The process of pH-sensitive fusion is ubiquitous to multiple viral families including orthomyxoviruses (influenza), filoviruses (Ebola virus, EBOV, and Marburg virus, MARV) and flaviviruses (Dengue virus, DENV, and Zika virus, ZIKV), some of which are considered major public health threats,43 and represents a fundamental barrier to spatial and temporal colocalization between viruses and inhibitors. Moreover, if inhibitors fail to diffuse across lipid membranes, they may only reach viral targets when endocytosed simultaneously. Here we report an HA2-derived fusion inhibitory peptide design against influenza with two structural features engineered to overcome this limitation: (i) chemical conjugation with a flexible PEG linker and lipophilic Chol or Toc moieties, and (ii) addition of an N-terminal Tat CPP domain (Table 1). While Chol or Toc are included to provide peptide partition toward cell membrane23,44 by concentrating the peptide on the membrane prior to virus attachment/endocytosis,16 Tat CPP domain, a canonical cell membrane translocating sequence,21,45 is introduced to promote peptide internalization.17,19 Tat is known to route peptides toward endosomes, as previously shown for EBOV fusion inhibitors.20 The combination of both strategies has been shown to greatly increase the transfection efficiency of conjugated peptides.46

Strikingly, inclusion of Tat resulted in enhanced inhibition of pH-triggered influenza fusion with liposomes by Tat-HA2Ec peptides, when compared with homologous HA2Ec peptides lacking Tat (Figure 2, C and D). Fusion kinetics in the presence of Tat-HA2Ec1–3 suggest that these peptides irreversibly prevent the progression of viral fusion to maximum control values, promoting inhibited steady-states. Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3, respectively, Chol- and Toc-conjugated peptides, had the largest effect on fusion kinetics. Since these peptides did not have a significant effect on lipid mixing kinetics (Figure 2, A and B), we suggest that the inhibitory mechanism may be associated with unrestricted hemifusion states, described in other contexts.47 Such a mechanism would be favored by a decrease in the population of functional HA glycoproteins, as a result of peptide binding, and establishment of large and stable hemifusion diaphragms.48,49 Under these conditions, lipid mixing is possible without the occurrence of complete fusion, in a longer time scale. Interestingly, Tat has been previously associated with lipid mixing.50 Our results, obtained in a system lacking energy-dependent translocation mechanisms, highlight the role of Tat in peptide design.

As reported for other fusion inhibitory peptides (and proteins), conjugation with lipophilic moieties correlates with improved influenza fusion inhibition.22,51 Lipid-conjugated antiviral peptide self-association and lipid membrane interactions, under relevant biological conditions, have been recently linked with in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetics and efficacy.23,28 Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 peptides, but not Tat-HA2Ec1, self-assemble in solution to form small NPs (DH ç 15−20 nM) with narrow size distribution profiles and moderate PDI (Figures S1 and 3). The NP size and PDI were stable for over 3 h (Figure 3). The formation of core–shell structured NPs from an amphiphilic peptide containing a C-terminal Tat sequence, PEG linker, and Chol has been reported to be associated with potent antimicrobial activity.52 NPs were considerably larger in this case (DH > 100 nm). We attribute the small nature of the described NPs to the Tat-HA2Ec sequence triple α-helical secondary structure motifs (Figure 1, B). Due to the interspaced random coil segments, peptides may assume compact arrangements, as found in the native HA2 structure and predicted by homology-based simulations (Figure 1). Small particles are usually suitable for efficient in vivo biodistribution, due to intrinsic evasion of host mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS) and only moderate clearance rates.53

Despite being stable in solution, Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 NPs underwent structural reorganization in the presence of POPC:Chol (2:1) lipid membranes, partitioning into the lipid phase (Figure 4, A–D). This behavior, assessed through a fluorescence spectroscopy approach, is required for peptide concentration in proximity to target HA. High Kp values suggest that peptide NP concentration in the aqueous phase is greatly reduced in the presence of membranes. Though free in solution, unconjugated Tat-HA2Ec1 peptides also adsorb toward lipid membranes, potentially due to the net cationic nature (Figure 4, D). Thus, both the peptide backbone and lipid may play an important role in the Tat-HA2Ec2 or Tat-HA2Ec3 lipid membrane partition. Others have shown that Tat-coated ritonavir-loaded NPs directly interact with lipid monolayers.54 The atypical partition profiles of these fusion inhibitory peptides suggest some degree of self-association (self-quenching of Trp) at the membrane-level, especially at low lipid concentrations.32 This does not exclude the membrane-guided disassembling of NPs, for higher lipid concentrations. In agreement with other fusion inhibitory peptides,55,56 the Tat-HA2Ec peptide backbone locates near the membrane interface, as probed by Trp amino acid residue localization within POPC:Chol (2:1) lipid membranes (Figure 4, E). Importantly, partition toward membranes does not seem to influence Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 peptide accessibility and exposure.

One of the major drawbacks of peptide-based therapeutics such as the previously reported fusion inhibitors is the low bioavailability and high clearance rates following administration.57 Unfortunately, injection routes are still the most commonly used and the least ideal for patient compliance. Nasal and pulmonary routes are becoming more prominent since the development of peptide-based nanopharmaceuticals,58 particularly for delivery of fusion inhibitory peptides.31,59 Peptides were noncytotoxic in an ex vivo HAE model and so are potentially safe for in vivo applications (Table 2). Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 peptide NPs delivered to cotton rats through noninvasive intranasal and intrapulmonary administration were detected at high levels 8 h postadministration (Figure 5, A). These were mainly found in peripheral pulmonary tissue, the main primary target of influenza infection and an ideal site for preventing the initial stages of infection. Tat-HA2Ec peptides were detected at considerably lower concentrations when injected subcutaneously, probably due to slow absorption and extensive degradation. Even though serum content is low, we cannot exclude that peptides reach tissues through circulating RBC and PBMC, since these act as reservoirs for cell membrane bound peptides (Figure 5, B and C).28,60 In the context of influenza infection, a quickly replicating virus, attaining maximum inhibitor concentration with short delay relative to the moment of administration is desirable. A Tat-conjugated antidepressant-like peptide was potent 2 h postadministration to Sprague–Dawley rats, evidencing the high rate of drug absorption through this route.61 Similar observations were reported for intranasally administrated vFlip-derived peptides containing Tat upon treatment of influenza infected BALB/c mice.62 Due to the lower antiviral load and administered volume required to achieve comparable Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 levels in relevant tissues (20 μL in cotton rats), the intranasal route is a suitable alternative for fusion inhibitor peptide NP delivery.

Table 2.

Tat-HAEc Peptide Cytotoxicity Evaluated in HAE Cell Cultures

| % HAE culture viability (±SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| incubation time/h | [peptide]/μM | Tat-HA2Ecl | Tat-HA2Ec2 | Tat-HA2Ec3 |

| 4 | 10 | 102.5 (±8.8) | 100.0 (±7.3) | 91.3 (±7.6) |

| 24 | 1 | 98.3 (±0.5) | 111.9 (±1.1) | 91.4 (±0.5) |

| 24 | 10 | 102.2 (±1.9) | 107.2 (±9.7) | 102.7 (±0.2) |

Intranasally delivered Tat-HA2Ec2 and Tat-HA2Ec3 peptide NPs decreased influenza viral titers in vivo, in the cotton rat nonlethal model of infection (Figure 6). Tat-HA2Ec1, which was used as a control, showed only a moderate effect on influenza titers, suggesting the importance of self-association and membrane incorporation/retention. Since Toc-conjugated Tat-HA2Ec3 NPs display significant prophylactic properties (Figure 6, B), we expect these fusion inhibitory peptides to be effective in both prevention and treatment in outbreak scenarios. An independent study addressing the prophylactic efficacy of a small Chol-conjugated fusion inhibitor peptide in an alternative animal model supports these observations.63 Even though the formation of peptide NPs was not discussed in this case, peptides were administered orally to mice without loss of antiviral effectiveness. Remarkably, multiple other peptides targeting HA2 protein conserved regions have shown promising results in in vitro and in vivo experiments.64–67 Peptides can target HA, directly or indirectly, through a plethora of molecular mechanisms, namely antibody-like neutralization, sialic acid receptor antagonism, and pH-triggered conformation inhibition, highlighting HA’s potential for anti-influenza peptide therapeutic development.

The in vivo effectiveness of our fusion inhibitor NPs was comparable to the widely used anti-influenza neuraminidase inhibitor zanamavir (Relenza) (Table S3). Zanamivir, like all drugs of this class, prevents the release of progeny virions from infected cells, since this release process requires cleavage of sialic acid receptors.68–71 A recombinant sialidase antiviral (Fludase) acts by cleaving cell surface sialic acids to prevent influenza binding and entry72–74 and is currently in clinical trials.75,76 Combining drugs that act via different mechanisms can increase antiviral efficacy as well as avoid the emergence of resistance to drug, as HIV HAART therapy has shown.77–79 Fludase and Relenza are directed at different stages of the viral life cycle. Fludase targets entry like our highly active fusion inhibitor peptide NPs; however, while Fludase blocks receptor binding, our peptides target the slightly later step of fusion and benefit from intracellular targeting (Figure 7). Thus, our peptides could be offered in combination with either of these two antivirals. A recent report showed that a fusion inhibitory peptide with an H7-derived sequence based on our design16 was effective against H7N9 influenza either alone or combined with NA inhibitors.80 Others have also shown that these antiviral peptides are effective against influenza strains resistant to NA inhibitors.63 We aim to harness influenza fusion inhibitors for use by themselves or in combination with Relenza – or Fludase if it is proven safe and effective – to manage and control influenza epidemics as well as emerging pandemic strains.81 Immune-compromised patients, in particular, would benefit from the anti-influenza approach under development in this study, since vaccination is not always an option for this group.

METHODS

Viruses.

Gradient-purified influenza A X-31 A/AICHI/68(H3N2) virus grown in specific pathogen-free embryonated chicken eggs was purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Samples (2 mg/mL of total viral protein) were centrifuged at 2500 g for 5 min (4 °C) to pellet any residual protein aggregates. Influenza A/Wuhan/359/95(H3N2) virus (a component of the influenza vaccine in years 1996–1997 and 1997–1998) was a gift from Gregory Prince, Virion Systems, Rockville, Maryland.

Peptides.

HA2Ec1, HA2Ec2, HA2Ec3, Tat-HA2Ec1, Tat-HA2Ec2, and Tat-HA2Ec3 were purchased from Pepscan (Table 1). Tat-VG1, Tat-VG2, and Tat-VG3 were purchased from American Peptide Company (Table S1). Peptides were initially solubilized in spectroscopic grade DMSO (Merck) to final concentrations of 3–50 mg/mL. For influenza virus fusion and lipid mixing experiments, peptides stock solutions were diluted in 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′−2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.5 buffer. For biophysical studies, peptide stock solutions were diluted in 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 buffer. For confocal microscopy, in vivo efficacy and biodistribution studies, peptide stock solutions were diluted in sterile water for injection (Hospira) or phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

Liposome Preparation.

Liposomes were prepared as previously described.82 Lipids were initially dissolved in spectroscopic grade chloroform (Merck) and dried in a round-bottom flask, under a gentle nitrogen flow. The resulting thin lipid film was further dried under vacuum conditions overnight to remove residual solvent. The lipid film was rehydrated with aqueous buffer (selected according to the peptide sample buffer used in each experiment) and subjected to 10 freeze/thaw cycles. The resulting multilamellar vesicles (MLV) suspension was extruded through a 100 nm pore polycarbonate membrane (Whatman, GE Healthcare) using a Mini-Extruder setup (Avanti), yielding a large unilamellar vesicle (LUV) suspension. LUV suspensions composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC, Avanti) and Chol (Sigma) combined at a 2:1 molar ratio or 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC, Avanti) were prepared.

For lipid mixing kinetics experiments, DOPC LUVs incorporating 2.5 mol % (relative to the total lipid content) of either N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (NBD-PE, Thermo) or Rhodamine B 1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (Rho-PE, Thermo) in the lipid membrane were prepared. Probes were cosolubilized with DOPC prior to lipid film formation, to allow efficient incorporation into the lipid bilayer upon rehydration. DOPC LUVs incorporating 1.25 mol % of each probe were also prepared for control experiments.

For fusion kinetics experiments, DOPC LUVs encapsulating 25 mM sulforhodamine B (SRho-B, Sigma) in the lumen were prepared. DOPC dried lipid films were rehydrated with 25 mM SRho-B prepared in 10 mM HEPES, 225 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.5 buffer. After extrusion, nonencapsulated SRho-B probe was removed through size exclusion chromatography using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare).

Instrumentation.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy was performed in a M1000 Pro microplate reader (Tecan). Steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy was performed in a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Varian). Time correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) fluorescence lifetime measurements were performed in a Lifespec II fluorometer (Edinburgh), equipped with an EPLED-280 source (λ = 275 nm, 200 ns pulse rate). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) size measurements were performed in a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern), equipped with backscattering detection at 173° and a He−Ne laser (λ = 632.8 nm). Nontreated 96-well black plates (Falcon) were used for time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy. 0.5 mm quartz cuvettes (Hellma) were used for steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy and TCSPC fluorescence lifetime measurements. A low-volume quartz cuvette (ZEN2112, Hellma) was used for DLS measurements. All measurements were performed at 25 °C, unless stated otherwise.

Influenza Virus Lipid Mixing and Fusion Kinetics.

In both lipid mixing and fusion kinetics experiments, influenza A X-31 viruses (0.1 mg/mL of total viral protein) were mixed with fluorescently labeled DOPC LUVs (0.2 mg/mL) preincubated with each peptide (10 μM) for 10 min. Control samples in the absence of peptide and/or virus were also prepared. To trigger influenza lipid mixing/fusion with LUVs, samples were acidified to pH 5.0 by addition of 10 mM HEPES, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 3.0 buffer.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy was used to monitor influenza-LUV lipid mixing and fusion kinetics. Lipid mixing was assessed through NBD-PE and Rho-PE energy transfer (FRET). An equimolar mixture of NBD-PE and Rho-PE-labeled DOPC LUV samples was prepared for this purpose. Probes emission spectra were scanned between 530 and 600 nm, with fixed excitation wavelength (λexc) at 470 nm. Spectra were collected every 30 s, over a 5 min period, prior to lipid mixing/fusion triggering to monitor baseline stability, and over a 1 h period, immediately after triggering. The extent of lipid mixing, i.e. NBD-PE/Rho-PE FRET, was quantified through the following formalism applied to spectral data

| (1) |

in which RD/A(t) corresponds to the ratio between NBD-PE (donor) and Rho-PE (acceptor) fluorescence emission intensity, integrated between 530 and 550 nm and 580 and 600 nm, respectively, at each time point; RD/A(0) corresponds to the ratio at the initial kinetics time point; RD/A(100%) corresponds to the ratio obtained for the control sample containing both probes in the same DOPC LUV membrane (equivalent to 100% lipid mixing).

Fusion was assessed through SRho-B dequenching, adapting a method described elsewhere.16 Probe fluorescence emission intensity was measured at 590 nm (emission maximum), using a λexc of 565 nm. Measurements were performed every 10 s, over a 5 min period, prior to triggering to monitor baseline stability, and over a 1 h period, immediately after triggering. At the end of each experiment, samples were solubilized with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma), to induce full probe dequenching. The extent of fusion, i.e. SRho-B dequenching, was quantified through the following formalism applied to the measured intensity

| (2) |

in which I590(t) corresponds to the SRho-B fluorescence emission intensity at 590 nm, measured at each time point; I590(0) corresponds to the respective intensity at the initial kinetics time point; and I590(100%) corresponds to the sample intensity after treatment with Triton X-100 (equivalent to 100% fusion).

Dynamic Light Scattering.

For DLS particle size measurements, peptide samples (10 μM) were preincubated at 25 °C for 5 min before starting each measurement. Steady-state and time-resolved measurements consisted in normalized scattered intensity autocorrelation curves, averaged from 10 successive runs or collected every 4 min over a 3 h period, respectively. Peptide diffusion coefficients (D) were obtained from autocorrelation curves using the CONTIN method,83 converted to particle DH values through the Stokes–Einstein equation,84 and plotted as particle number-averaged size distribution profiles (0–50 nm). Average polydispersity index (PDI) values were determined from size profiles through the relationship , in which is the average DH, and SD is the respective standard deviation.

Fluorescence Quenching.

Peptide tryptophan residue (Trp) fluorescence quenching by acrylamide was carried out by successive additions of acrylamide (Sigma) solution to peptide samples (5 μM), leading to final quencher concentrations between 0 and 60 mM. Experiments were performed in aqueous solution and in the presence of POPC:Chol (2:1) LUVs (3 mM). For every addition, a minimal 10 min incubation time was allowed before measurements. Peptide Trp steady-state fluorescence emission was collected at 350 nm (emission maximum), using a fixed λexc of 290 nm, to minimize acrylamide absorption. Excitation and emission spectral bandwidths were 5 and 10 nm, respectively. Emission was corrected for successive dilutions, background, and simultaneous light absorption by quencher and fluorophore.85 Quenching data was analyzed using the Stern–Volmer formalism86

| (3) |

where I and I0 are the sample fluorescence intensity in the presence and absence of quencher, respectively, KSV is the Stern–Volmer constant, and [Q] is the quencher concentration. When a negative deviation to the Stern–Volmer relationship was observed, the modified Stern–Volmer equation was applied86

| (4) |

in which fb is the fraction of the fluorophore population accessible to the quencher.

Peptide Trp fluorescence quenching by lipophilic quenchers 5NS and 16NS was carried out at the same peptide and lipid concentrations used in acrylamide quenching experiments, by successive additions of either 5NS or 16NS (Sigma) solution in ethanol to peptide samples in POPC:Chol (2:1) LUVs. Ethanol content was kept below 2% (v/v). The effective lipophilic quencher concentration in the membrane was calculated from the partition constant (Kp) of both quenchers to the lipid bilayers.87 A minimal 10 min incubation time was allowed before measurements. Peptide Trp Time Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) fluorescence intensity decays were collected between 0 and 20 ns, using a pulse excitation at 275 nm and detection at 350 nm (20 nm bandwidth). Fluorescence lifetimes, τ, were determined from multiexponential intensity decay fits through a nonlinear least-squares method. Quenching data was analyzed using eq 3, assuming that I0/I = τ0/τ is valid under dynamic quenching conditions. In-depth location distribution profiles were predicted as previously described.33

Membrane Partition.

Peptide membrane partition studies were performed by successive additions of small volumes of POPC:Chol (2:1) LUV suspension to each peptide sample (5 μM), leading to final LUV concentrations up to 5 mM. A 10 min incubation time was allowed between measurements. Peptide Trp steady-state fluorescence emission was collected between 310 and 450 nm, using a fixed λexc of 280 nm. Excitation and emission slits were 5 and 10 nm, respectively. Emission was corrected for successive dilutions, background, and light scattering effects.88 Membrane Kp’s were calculated using the following partition equation89

| (5) |

where IW and IL are the integrated fluorescence emission intensities in aqueous solution and in lipid, respectively, γL is the lipid molar volume, and [L] is the lipid concentration. When deviations to the previous equation were observed, the Kp was calculated using the following alternative formalism, accounting for fluorophore self-quenching32

| (6) |

in which k2 is a proportionality constant related to self-quenching efficiency.

Cell Membrane Dipole Potential Perturbation.

Human blood samples were collected from healthy donors under written informed consent at the Instituto Português do Sangue (Lisbon, Portugal). Experiments were performed with the approval of the ethics committee of the Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa. RBC and PBMC isolation and labeling with di-8-ANEPPS (Invitrogen) were performed as previously described.60 To isolate RBC, blood samples were centrifuged at 1200×g for 10 min, followed by removal of plasma and buffy-coat. RBC were washed twice with sample buffer and then incubated at 1% hematocrit in sample buffer supplemented with 0.05% (m/v) Pluronic F-127 (Sigma) and di-8-ANEPPS (10 μM). PBMC were isolated by density gradient using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield) and counted in a MOXI Z Mini Automated Cell Counter (Orflo). PBMC were incubated at 3 × 103 cells/μL in Pluronic-supplemented sample buffer with di-8-ANEPPS (3.3 μM). RBC and PBMC were allowed to incorporate di-8-ANEPPS for 1 h, under gentle agitation. Unbound probe was washed with Pluronic-free sample buffer, after two centrifugation cycles. Peptides were incubated with RBC at 0.02% hematocrit and with PBMC at 1 × 102 cells/μL for a period of 1 h, under gentle agitation, before performing fluorescence measurements. di-8-ANEPPS steady-state fluorescence excitation spectra were collected between 380 and 580 nm, with an emission wavelength fixed at 670 nm to avoid membrane fluidity artifacts.90 Excitation and emission slits were set to 5 and 10 nm, respectively. Spectral shifts were quantified through excitation intensity ratios (Rnorm), calculated through the relationship R = Iexc(455)/Iexc(525) and normalized to the control spectrum R, obtained in the absence of peptide.

Peptide Cytotoxicity in HAE Cultures.

The EpiAirway AIR-100 system (MatTek Corporation) consists of normal human-derived tracheo/bronchial epithelial cells that have been cultured to form a pseudostratified, highly differentiated mucociliary epithelium closely resembling that of epithelial tissue in vivo. Upon receipt from the manufacturer, HAE cultures were transferred to 6-well plates (containing 0.9 mL medium per well) with the apical surface remaining exposed to air and incubated at 37 °C, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. HAE cultures were incubated at 37 °C in the absence or presence of 1 or 10 μM of Tat-HAEc1, Tat-HAEc2, and Tat-HAEc3 peptides. Peptides were added to the apical side of cells. Cell viability was determined after 4 or 24 h incubation using the MTT-100 colorimetric detection system (MatTek), specifically designed for EpiAirway cultures, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

For biodistribution studies, each organ was weighed and mixed in PBS (1:1, w/v) using an ultra-turrax homogenizer. Samples were then treated with acetonitrile/1% trifluoroacetic acid (1:4, v/v) for 1 h on a rotor at 4 °C and then centrifuged for 10 min, at 8000 rpm. Supernatant fluids were collected, and peptide concentration was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Maxisorp 96 well plates (Nunc) were coated overnight with purified rabbit anti-HA-derived-peptide antibodies (5 μg/mL) in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, pH 7.4. Plates were washed twice using PBS followed by incubation with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS (blocking buffer) for 30 min. The blocking buffer was replaced with 2 dilutions of each sample in 3% PBS-BSA in duplicate and incubated for 90 min at room temperature (RT). After multiple washes in PBS, the peptide was detected using an HRP-conjugated rabbit custom-made anti-HA2-derived-peptide antibody (1:1500) in blocking buffer for 2 h, at RT. HRP activity was recorded as absorbance at 492 nm on the Sigmafast o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) substrate system (Sigma-Aldrich) after adding the stop solution. Standard curves were established for each peptide (using the same ELISA conditions as for the test samples), and the detection limit was determined to be 0.15 nM.

Biodistribution Analysis and Infection of Cotton Rats.

Inbred cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories, Inc. Both male and female cotton rats at the age of 5 to 7 weeks were used. For biodistribution experiments in cotton rats, animals received the indicated peptides (5 mg/kg) through the nasal route with 100 μL of diluent (to mimic intralung delivery), or with 20 μL of diluent (to mimic intranasal delivery), or subcutaneously with 200 μL in isofluorance narcosis. After 8 h, blood was collected by intracardiac puncture in EDTA vacutainer tubes, and sera were conserved at −20 °C until used in ELISA. Organs from each animal were collected and conserved at −80 °C.

For intranasal infection, animals were inoculated with 106 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) of influenza A/Wuhan/359/95(H3N2) in PBS in isoflurane narcosis in a volume of 100 μL. To evaluate the effect of fusion inhibitory peptides, animals were inoculated intranasally with peptide (5 mg/kg, 20 μL) or vehicle (sterile water for injection, 20 μL) as indicated. Three days after infection, the animals were asphyxiated using CO2, and the titer from nose homogenates was assessed. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ohio State University.

Peptides Localization in Live Cells.

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) and incubated at 37 °C, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For experiments, cells were seeded in a 96-well black plate (Corning) at 5 × 105 cells/well and incubated overnight. HA2Ec1, HA2Ec2, Tat-HA2Ec2, and Tat-HA2Ec3 peptides (dissolved in DMSO to 1 mM) were diluted in PBS to 100 μM and incubated at RT for 24 h. Peptides were added to live cells for a final concentration of 1.5 μM and allowed to incubate for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed with 1% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.02% Tween-20 in PBS, and stained with a custom-made anti-HA2Ec antibody (mouse) for peptides and with DAPI for nuclei. The anti-HA2EC antibodies were detected using an Alexa Fluor 488-tagged anti-mouse secondary antibody.

Data Analysis.

Fitting of the equations mentioned in this article to the experimental data was done by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism. Error bars on data presentation represent the standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.P. acknowledges grants R01AI121349 and R01AI119762 funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). T.N.F. acknowledges individual fellowships SFRH/BD/5283/2013 funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT-MCTES). A.S.V. acknowledges funding under the Investigator Programme (IF/00803/2012) from FCT-MCTES. This work was supported by FCT-MCTES projects PTDC/QEQ-MED/4412/2014 and PTDC/BBB-BQB/3494/2014.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00527.

Description of the studied peptides (Table S1), influenza virus lipid mixing and fusion kinetics controls (Figure S1), peptide aggregation screening (Figure S2), complementary fluorescence emission quenching analysis (Figure S3), peptide biophysical parameters (Table S2), and in vivo efficacy controls (Table S3) (PDF)

Video compiling sequential z-axis confocal fluorescence micrograph (Video S1) (AVI)

Video compiling sequential z-axis confocal fluorescence micrograph (Video S2) (AVI)

Video compiling sequential z-axis confocal fluorescence micrograph (Video S3) (AVI)

Video compiling sequential z-axis confocal fluorescence micrograph (Video S4) (AVI)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hay AJ, and McCauley JW (2018) The WHO global influenza surveillance and response system (GISRS)-A future perspective. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 12, 551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, Wu P, Kyncl J, Ang LW, Park M, Redlberger-Fritz M, Yu H, Espenhain L, Krishnan A, Emukule G, van Asten L, Pereira da Silva S, Aungkulanon S, Buchholz U, Widdowson M-A, Bresee JS, and Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network (2018) Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 391, 1285–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Xie H, Wan X-F, Ye Z, Plant EP, Zhao Y, Xu Y, Li X, Finch C, Zhao N, Kawano T, Zoueva O, Chiang M-J, Jing X, Lin Z, Zhang A, and Zhu Y (2015) H3N2Mismatch of 2014–15 Northern Hemisphere Influenza Vaccines and Head-to-head Comparison between Human and Ferret Antisera derived Antigenic Maps. Sci. Rep 5, 15279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, Sundaram ME, Kelley NS, Osterholm MT, and McLean HQ (2016) Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect. Dis 16, 942–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Tricco AC, Chit A, Soobiah C, Hallett D, Meier G, Chen MH, Tashkandi M, Bauch CT, and Loeb M (2013) Comparing influenza vaccine efficacy against mismatched and matched strains: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 11, 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, McLean HQ, Gaglani M, Murthy K, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Jackson ML, Jackson LA, Monto AS, Martin ET, Foust A, Sessions W, Berman L, Barnes JR, Spencer S, and Fry AM (2018) Interim Estimates of 2017−18 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness - United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 67, 180–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, De Serres G, Sabaiduc S, Eshaghi A, Dickinson JA, Fonseca K, Winter A-L, Gubbay JB, Krajden M, Petric M, Charest H, Bastien N, Kwindt TL, Mahmud SM, Van Caeseele P, and Li Y (2014) Low 2012−13 influenza vaccine effectiveness associated with mutation in the egg-adapted H3N2 vaccine strain not antigenic drift in circulating viruses. PLoS One 9, e92153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hayden FG (2013) Newer influenza antivirals, biotherapeutics and combinations. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 7, 63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Koszalka P, Tilmanis D, and Hurt AC (2017) Influenza antivirals currently in late-phase clinical trial. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 11, 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Carr CM, and Kim PS (1993) A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell 73, 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Carr CM, Chaudhry C, and Kim PS (1997) Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 94, 14306–14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Stevens J, Corper AL, Basler CF, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, and Wilson IA (2004) Structure of the uncleaved human H1 hemagglutinin from the extinct 1918 influenza virus. Science 303, 1866–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chen J, Lee KH, Steinhauer DA, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, and Wiley DC (1998) Structure of the hemagglutinin precursor cleavage site, a determinant of influenza pathogenicity and the origin of the labile conformation. Cell 95, 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chen J, Skehel JJ, and Wiley DC (1999) N- and C-terminal residues combine in the fusion-pH influenza hemagglutinin HA(2) subunit to form an N cap that terminates the triple-stranded coiled coil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 96, 8967–8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Park HE, Gruenke JA, and White JM (2003) Leash in the groove mechanism of membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 10, 1048–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lee KK, Pessi A, Gui L, Santoprete A, Talekar A, Moscona A, and Porotto M (2011) Capturing a fusion intermediate of influenza hemagglutinin with a cholesterol-conjugated peptide, a new antiviral strategy for influenza virus. J. Biol. Chem 286, 42141–42149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Milletti F (2012) Cell-penetrating peptides: classes, origin, and current landscape. Drug Discovery Today 17, 850–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bechara C, and Sagan S (2013) Cell-penetrating peptides: 20 years later, where do we stand? FEBS Lett. 587, 1693–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Reissmann S (2014) Cell penetration: scope and limitations by the application of cell-penetrating peptides. J. Pept. Sci 20, 760–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Higgins CD, Koellhoffer JF, Chandran K, and Lai JR (2013) C-peptide inhibitors of Ebola virus glycoprotein-mediated cell entry: effects of conjugation to cholesterol and side chain-side chain crosslinking. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 23, 5356–5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Green M, and Loewenstein PM (1988) Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell 55, 1179–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pessi A, Langella A, Capitò E, Ghezzi S, Vicenzi E, Poli G, Ketas T, Mathieu C, Cortese R, Horvat B, Moscona A, Porotto M, and Liang C (2012) A General Strategy to Endow Natural Fusion-protein-Derived Peptides with Potent Antiviral Activity. PLoS ONE 7, e36833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Figueira TN, Palermo LM, Veiga AS, Huey D, Alabi CA, Santos NC, Welsch JC, Mathieu C, Horvat B, Niewiesk S, Moscona A, Castanho MARB, and Porotto M (2016) In Vivo Efficacy of Measles Virus Fusion Protein-Derived Peptides Is Modulated by the Properties of Self-Assembly and Membrane Residence. J. Virol 91, e01554–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, Xu D, Poisson J, and Zhang Y (2015) The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Methods 12, 7–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Buchan DWA, Minneci F, Nugent TCO, Bryson K, and Jones DT (2013) Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Gautam A, Chaudhary K, Kumar R, Sharma A, Kapoor P, Tyagi A, and Raghava GPS (2013) In silico approaches for designing highly effective cell penetrating peptides. J. Transl. Med 11, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, and Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mathieu C, Augusto MT, Niewiesk S, Horvat B, Palermo LM, Sanna G, Madeddu S, Huey D, Castanho MARB, Porotto M, Santos NC, and Moscona A (2017) Broad spectrum antiviral activity for paramyxoviruses is modulated by biophysical properties of fusion inhibitory peptides. Sci. Rep 7, 43610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dehsorkhi A, Castelletto V, and Hamley IW (2014) Self-assembling amphiphilic peptides. J. Pept. Sci 20, 453–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hawe A, Sutter M, and Jiskoot W (2008) Extrinsic fluorescent dyes as tools for protein characterization. Pharm. Res 25, 1487–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Mathieu C, Huey D, Jurgens E, Welsch JC, DeVito I, Talekar A, Horvat B, Niewiesk S, Moscona A, and Porotto M (2015) Prevention of measles virus infection by intranasal delivery of fusion inhibitor peptides. J. Virol 89, 1143–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Henriques ST, and Castanho MARB (2005) Environmental factors that enhance the action of the cell penetrating peptide pep-1 A spectroscopic study using lipidic vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1669, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Fernandes MX, Garcıá de la Torre J, and Castanho MARB (2002) Joint determination by Brownian dynamics and fluorescence quenching of the in-depth location profile of biomolecules in membranes. Anal. Biochem 307, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Porotto M, Rockx B, Yokoyama CC, Talekar A, DeVito I, Palermo LM, Liu J, Cortese R, Lu M, Feldmann H, Pessi A, and Moscona A (2010) Inhibition of Nipah virus infection in vivo: targeting an early stage of paramyxovirus fusion activation during viral entry. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Mosmann T (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).van Meerloo J, Kaspers GJL, and Cloos J (2011) Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. Methods Mol. Biol 731, 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Eyles JE, Bramwell VW, Williamson ED, and Alpar HO (2001) Microsphere translocation and immunopotentiation in systemic tissues following intranasal administration. Vaccine 19, 4732–4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Visweswaraiah A, Novotny LA, Hjemdahl-Monsen EJ, Bakaletz LO, and Thanavala Y (2002) Tracking the tissue distribution of marker dye following intranasal delivery in mice and chinchillas: a multifactorial analysis of parameters affecting nasal retention. Vaccine 20, 3209–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Southam DS, Dolovich M, O’Byrne PM, and Inman MD (2002) Distribution of intranasal instillations in mice: effects of volume, time, body position, and anesthesia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 282, L833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Miller MA, Stabenow JM, Parvathareddy J, Wodowski AJ, Fabrizio TP, Bina XR, Zalduondo L, and Bina JE (2012) Visualization of murine intranasal dosing efficiency using luminescent Francisella tularensis: effect of instillation volume and form of anesthesia. PLoS One 7, e31359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Porotto M, Palmer SG, Palermo LM, and Moscona A (2012) Mechanism of fusion triggering by human parainfluenza virus type III: communication between viral glycoproteins during entry. J. Biol. Chem 287, 778–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Zhou Y, and Simmons G (2012) Development of novel entry inhibitors targeting emerging viruses. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther 10, 1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Marston HD, Folkers GK, Morens DM, and Fauci AS (2014) Emerging viral diseases: confronting threats with new technologies. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 253ps10–253ps10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Augusto MT, Hollmann A, Castanho MARB, Porotto M, Pessi A, and Santos NC (2014) Improvement of HIV fusion inhibitor C34 efficacy by membrane anchoring and enhanced exposure. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 69, 1286–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Fawell S, Seery J, Daikh Y, Moore C, Chen LL, Pepinsky B, and Barsoum J (1994) Tat-mediated delivery of heterologous proteins into cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 91, 664–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Futaki S, Ohashi W, Suzuki T, Niwa M, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Harashima H, and Sugiura Y (2001) Stearylated Arginine-Rich Peptides: A New Class of Transfection Systems. Bioconjugate Chem. 12, 1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Chernomordik LV, Frolov VA, Leikina E, Bronk P, and Zimmerberg J (1998) The pathway of membrane fusion catalyzed by influenza hemagglutinin: restriction of lipids, hemifusion, and lipidic fusion pore formation. J. Cell Biol. 140, 1369–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Nikolaus J, Stöckl M, Langosch D, Volkmer R, and Herrmann A (2010) Direct visualization of large and protein-free hemifusion diaphragms. Biophys. J 98, 1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Warner JM, and O’Shaughnessy B (2012) Evolution of the hemifused intermediate on the pathway to membrane fusion. Biophys. J 103, 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Yang S-T, Zaitseva E, Chernomordik LV, and Melikov K (2010) Cell-penetrating peptide induces leaky fusion of liposomes containing late endosome-specific anionic lipid. Biophys. J 99, 2525–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Porotto M, Yokoyama CC, Palermo LM, Mungall B, Aljofan M, Cortese R, Pessi A, and Moscona A (2010) Viral entry inhibitors targeted to the membrane site of action. J. Virol 84, 6760–6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Liu L, Xu K, Wang H, Jeremy Tan PK, Fan W, Venkatraman SS, Li L, and Yang Y-Y (2009) Self-assembled cationic peptide nanoparticles as an efficient antimicrobial agent. Nat. Nanotechnol 4, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Gustafson HH, Holt-Casper D, Grainger DW, and Ghandehari H (2015) Nanoparticle Uptake: The Phagocyte Problem. Nano Today 10, 487–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Peetla C, Rao KS, and Labhasetwar V (2009) Relevance of Biophysical Interactions of Nanoparticles with a Model Membrane in Predicting Cellular Uptake: Study with TAT Peptide-Conjugated Nanoparticles. Mol. Pharmaceutics 6, 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Veiga S, Henriques S, Santos NC, and Castanho M (2004) Putative role of membranes in the HIV fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide mode of action at the molecular level. Biochem. J 377, 107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hollmann A, Matos PM, Augusto MT, Castanho MARB, and Santos NC (2013) Conjugation of Cholesterol to HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitor C34 Increases Peptide-Membrane Interactions Potentiating Its Action. PLoS ONE 8, e60302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Lewis AL, and Richard J (2015) Challenges in the delivery of peptide drugs: an industry perspective. Ther. Delivery 6, 149–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Thwala LN, Préat V, and Csaba NS (2017) Emerging delivery platforms for mucosal administration of biopharmaceuticals: a critical update on nasal, pulmonary and oral routes. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 14, 23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Mathieu C, Porotto M, Figueira TN, Horvat B, and Moscona A (2018) Fusion Inhibitory Lipopeptides Engineered for Prophylaxis of Nipah Virus in Primates. J. Infect. Dis 218, 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Matos PM, Freitas T, Castanho MA, and Santos NC (2010) The role of blood cell membrane lipids on the mode of action of HIV-1 fusion inhibitor sifuvirtide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 403, 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Brown V, and Liu F (2014) Intranasal delivery of a peptide with antidepressant-like effect. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2131–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Moon H-J, Nikapitiya C, Lee H-C, Park M-E, Kim J-H, Kim T-H, Yoon J-E, Cho W-K, Ma JY, Kim C-J, Jung JU, and Lee J-S (2017) Inhibition of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus by a peptide derived from vFLIP through its direct destabilization of viruses. Sci. Rep 7, 4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lin D, Luo Y, Yang G, Li F, Xie X, Chen D, He L, Wang J, Ye C, Lu S, Lv L, Liu S, and He J (2017) Potent influenza A virus entry inhibitors targeting a conserved region of hemagglutinin. Biochem. Pharmacol 144, 35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Memczak H, Lauster D, Kar P, Di Lella S, Volkmer R, Knecht V, Herrmann A, Ehrentreich-Förster E, Bier FF, Stöcklein WFM, and Krammer F (2016) Anti-Hemagglutinin Antibody Derived Lead Peptides for Inhibitors of Influenza Virus Binding. PLoS ONE 11, e0159074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Chen Q, and Guo Y (2016) Influenza Viral Hemagglutinin Peptide Inhibits Influenza Viral Entry by Shielding the Host Receptor. ACS Infect. Dis 2, 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Zhao H, Zhou J, Zhang K, Chu H, Liu D, Poon VK-M, Chan CC-S, Leung H-C, Fai N, Lin Y-P, Zhang AJ-X, Jin D-Y, Yuen K-Y, and Zheng B-J (2016) A novel peptide with potent and broad-spectrum antiviral activities against multiple respiratory viruses. Sci. Rep 6, 22008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Kadam RU, Juraszek J, Brandenburg B, Buyck C, Schepens WBG, Kesteleyn B, Stoops B, Vreeken RJ, Vermond J, Goutier W, Tang C, Vogels R, Friesen RHE, Goudsmit J, van Dongen MJP, and Wilson IA (2017) Potent peptidic fusion inhibitors of influenza virus. Science 358, 496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Yen H-L, Herlocher LM, Hoffmann E, Matrosovich MN, Monto AS, Webster RG, and Govorkova EA (2005) Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza viruses may differ substantially in fitness and transmissibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 4075–4084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Hurt AC, Iannello P, Jachno K, Komadina N, Hampson AW, Barr IG, and McKimm-Breschkin JL (2006) Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant and -sensitive influenza B viruses isolated from an untreated human patient. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 1872–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Monto AS, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Macken C, Hampson AW, Hay A, Klimov A, Tashiro M, Webster RG, Aymard M, Hayden FG, and Zambon M (2006) Detection of influenza viruses resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors in global surveillance during the first 3 years of their use. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2395–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Kacergius T, Ambrozaitis A, Deng Y, and Gravenstein S (2006) Neuraminidase inhibitors reduce nitric oxide production in influenza virus-infected and gamma interferon-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Pharmacol Rep 58, 924–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Belser JA, Lu X, Szretter KJ, Jin X, Aschenbrenner LM, Lee A, Hawley S, Kim DH, Malakhov MP, Yu M, Fang F, and Katz JM (2007) DAS181, a novel sialidase fusion protein, protects mice from lethal avian influenza H5N1 virus infection. J. Infect. Dis 196, 1493–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Triana-Baltzer GB, Gubareva LV, Nicholls JM, Pearce MB, Mishin VP, Belser JA, Chen L-M, Chan RWY, Chan MCW, Hedlund M, Larson JL, Moss RB, Katz JM, Tumpey TM, and Fang F (2009) Novel pandemic influenza A(H1N1) viruses are potently inhibited by DAS181, a sialidase fusion protein. PLoS One 4, e7788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]