Abstract

As whole-exome/genome sequencing data become increasingly available in genetic epidemiology research consortia, there is emerging interest in testing the interactions between rare genetic variants and environmental exposures that modify the risk of complex diseases. However, testing rare-variant-based gene-by-environment interactions (GxE) is more challenging than testing the genetic main effects due to the difficulty in correctly estimating the latter under the null hypothesis of no GxE effects and the presence of neutral variants. In response, we have developed a family of powerful and data-adaptive GxE tests, called “aGE” tests, in the framework of the adaptive powered score test, originally proposed for testing the genetic main effects. Using extensive simulations, we show that aGE tests can control the type I error rate in the presence of a large number of neutral variants or a nonlinear environmental main effect, and the power is more resilient to the inclusion of neutral variants than that of existing methods. We demonstrate the performance of the proposed aGE tests using Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium Exome Chip data. An R package “aGE” is available at http://github.com/ytzhong/projects/.

Keywords: Data-adaptive hypothesis testing, Rare variant, Gene-environment interaction, Model misspecification

1. Introduction

Complex diseases are likely to be the consequence of the interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Identification of gene-by-environment interaction (GxE) not only contributes to finding novel genetic loci, but also improves our understanding of disease mechanisms. A large number of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified thousands of genetic loci that are associated with complex diseases; however, heritability for a given complex disease cannot yet be fully explained by those loci. The broad-sense heritability model supports that gene-by-gene interactions, GxE, and epigenetic factors contribute to the so-called “missing heritability” problem.1–3 Indeed, novel loci have been identified with different complex diseases through GxE analysis, underscoring its important role in disease/trait gene discovery.4,5 In addition, environmental exposure, as a modifiable risk factor, can significantly impact the relationship between genetic variants and disease risk.6 GxE analysis serves as a starting point to understand the underlying biological mechanisms of complex diseases, which can be helpful for prevention and early detection of disease.7–11 One GxE example in alcohol-related cancer risk has wide acceptance among researchers and robust replication of findings: Wu et al. reported that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the alcohol metabolism pathway, including the encoding aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) gene and alcohol dehydrogenase gene cluster, interact with alcohol intake to promote the risk of esophageal cancer.4,7,12,13 Brooks et al. suggested that a great number of esophageal cancer cases might be prevented if ALDH2-deficient heavy drinkers reduced alcohol consumption.12

As next-generation sequencing (NGS) data, including whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing data, become increasingly available in large genetic epidemiology research consortia, more researchers have shifted their attention from common variants (CVs) with minor allele frequency (MAF) larger than 5% in GWAS to rare variants (RVs) with MAF less than 5% or 1%.2,14,15 RV analysis is complementary to CV analysis in terms of identifying novel genes and locating causal variants.16,17 Single-variant-based association tests are commonly used in CV analysis of GWAS, yet severe power loss occurs in RV analysis due to the low MAF. To date, many statistical methods have been proposed to increase the statistical power by aggregating RVs in a set, for example, grouping RVs in a gene, pathway, or any functional region. The power gain of such set-based methods is mainly owing to the decrease in the multiple testing burden and the genetic architecture, where multiple RVs in the set are associated with the disease/trait of interest. Nevertheless, the power gain of these methods usually relies on the true yet rarely known relationship between each RV and the given disease/trait. A well-known category of set-based methods is the burden test. Burden tests collapse RVs into genetic scores, which are most powerful when all RVs in the set are causal and have effects in the same direction.18,19 Another category of RV tests is variance-component tests, which assume that the genetic effects follow a distribution with both positive and negative directions. They are more powerful than the burden tests in the presence of RVs with opposite effects or non-associated neutral variants.20–22 In addition, researchers have developed tests that combine burden and variance-component tests to gain power across broader association patterns.23 The adaptive sum of powered score (aSPU) test is one of such combination tests that has shown to be powerful and adaptive to varying genetic architecture, particularly when there is a large proportion of neutral variants.24 All of the aforementioned set-based methods have focused on the genetic main effects rather than the GxE effects; however, limited work has been done on testing for rare-variant-based GxE analysis.

GxE analysis involves unique challenges. First, the genetic main effects need to be estimated in the model under the null hypothesis of no GxE. While the score test for the main effect analysis only entails fitting a null model with a small number of covariates, for which the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method suffices, MLE has been shown to lead to poor estimation of the genetic main effects in the null model for GxE, resulting in an inflated type I error rate.25,26 In addition, as NGS technology captures genetic variants in essentially single-base resolution, more RVs are likely to be included in the test sets, which further increases the difficulty in model estimation. rareGE and iSKAT are two state-of-the-art methods that deal with this problem, under the variance component test framework.25,27 They utilize a bias-variance trade-off to obtain more stable estimates of the genetic main effects in the null model, but shrink the parameter estimates differently. rareGE uses a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) and treats the genetic main effects as random effects, whereas iSKAT uses weighted ridge regression coupled with a generalized cross-validation method to select the tuning parameter. Recently, Coombes et al. proposed a CV-by-environment interaction test that employs ridge regression and is similar to iSKAT.28 Second, there could be substantial power loss if a large number of neutral RVs are included in GxE analysis. This problem also exists in tests of the genetic main effects, but it is even more challenging in the GxE analysis. There might be far fewer RVs interacting with the environmental variable than associated with the disease/trait of interest only through the main effects. Therefore, it is worth evaluating how the existing methods perform when the RV set is large and includes a large number of neutral RVs. Third, the inclusion of environmental variables into genetic epidemiology studies raises additional challenges in parametric modeling, which features parsimonious model assumptions. For example, a linear relationship between the environmental variable and the phenotype is frequently assumed. However, when the true relationship is beyond linear, model misspecification is likely to occur. Strangely behaving quantile-quantile (QQ) plots have been reported for testing single-variant-by-environment interaction due to misspecification of the main effect of the environmental variable.29–31 Set-based GxE tests are likely to encounter similar problems. In our motivating data example (detailed later), pack-years of cigarette smoking have a nonlinear relationship with the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Previous studies categorized subjects into non-smokers, light smokers, or heavy smokers based on pack-years of cigarette smoking. However, we found that the relationship between pack-years of smoking and cancer risk is more complicated than these three categories can capture, thus such simple categorization may lose much information in smoking exposure and may lead to loss of power. Therefore, we should fully utilize the continuous environmental variable of interest, e.g., pack-years, and at the same time, avoid model misspecification to maintain the type I rate. In summary, powerful and robust methods for testing GxE tailored for RVs are in need.

To fill the gaps, we propose a family of tests called adaptive gene-environment interaction (aGE) tests, with a focus on case-control studies. Our method is developed under the framework of the aSPU test, which maintains high power when testing the genetic main effects in the presence of a large number of neutral RVs.24 We show that inflated type I error rates can arise when the model is misspecified and provide a spline-based approach to tackle this problem. In addition, we have developed an aGE joint test to gain extra power across a broader set of penetrance models.32

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows. We review the aSPU test and present the new aGE method in Section 2. We present a simulation study to demonstrate the operating characteristics of the proposed method in Section 3, followed by application to a case-control study of pancreatic cancer to identify biological pathway-by-smoking interactions in Section 4. We conclude with a short discussion and future directions in Section 5.

2. Methods

2.1. Notations

Let yi be the phenotype of individual i; y=[y1, y2, …,yn]T, and n is the number of subjects. Here, we assume yi is binary in the case-control study design, though continuous phenotypes can be equally accommodated within the same framework. Xi is the vector of covariates for individual i with length p+ 2, including the intercept and the environmental variable Ei: Xi, = [1, Ei, Xi1, Xi2, Xip]. Gi is the genotype vector of length q for individual i: Gi= [Gi1,Gi2, … Giq], where Gik is the number of minor alleles of the kth RV in a set for the ith individual. Si is a vector of the product of Gi and Ei: Si= [Gi1 Ei, Gi2 Ei, …, Giq Ei,]. In addition, we assume X,G and S are n × (p+2), n × q and n × q matrices that contain all the subjects, and E is the vector of Ei of all the individuals: For example, and . In this paper, we assume the subjects are independent. We denote parameters without hat as true values and parameters with hat as estimated values.

2.2. Review of the aSPU test

The aSPU test has been shown to have superior performance in testing the genetic main effects under a wide range of association patterns, including varying association directions, effect sizes, and the presence of a large number of neutral variants. Consider the following generalized linear model:

where g(⋅) is the link function, μi is the mean of yi, β0 and are the coefficients of the covariates and the genetic main effects, respectively. Since the aSPU test focuses on testing the genetic main effects, the corresponding null hypothesis is H0 : β1k =0 for k =1,…,q. The alternative hypothesis is H1 : at least one element of β1 is not equal to 0.

Briefly, the aSPU test chooses the most powerful test among a family of sum of powered score (SPU) tests, including the sum (burden) test and the sequence kernel machine association test (SKAT) test/sum of squared test (SSU).20,24 The test statistic of an SPU test of positive integer power γ ≥ 1 (SPU(γ)) can be written as

with q RVs in the set. is the score function of the kth RV. When γ =1, the SPU(1) test uses constant 1 as a weight and sums the individual score function component Uk of all the RVs in the set of interest, equivalent to the Sum test or burden test; when γ =2, the SPU(2) test uses U as the weight to itself and is equivalent to variance-component test SKAT/SSU; when γ keeps increasing, the SPU(γ) test puts higher weights on the kth RV with larger |Uk|, while gradually decreasing the weights of other RVs with smaller |Uk|. As a large value of |Uk| indicates strong association strength of the kth RV with the phenotype, and a small value of |Uk| indicates weak or no association of the kth RV with the phenotype, a larger γ tends to put more weight on the informative RVs. According to the definition of p-norm, we have , which is a monotone increasing function of TSPU(γ) for even γ. As γ → ∞,

Thus, SPU(∞) test is closely related to the minimum p-value test, which only considers the RV with the most extreme test statistic in the set, except that the variance of each score component is approximated by a constant. Since there is no uniformly most powerful test, different γ may have varying performance. By adaptively choosing the most powerful test in the family of SPU tests, the aSPU test obtains high power across a wide range of scenarios. Of note, the aSPU test gains its adaptiveness at the cost of some power loss due to looking at multiple γ’s, compared to the most powerful test under a given scenario; however, the power loss is usually minor. Practically, γ taking values in Γ= {1, 2, 3, …, ∞} suffice to achieve optimal power in many applications. The multiple p-values are combined as follows:

where PSPU(γ) is the p-value of TSPU(γ). Since TaSPU is no longer a genuine p-value, permutation or parametric bootstrap is needed to obtain the final p-value for the aSPU test.

2.3. New method: aGE interaction test

To perform RV-set-based GxE analysis, we model the environmental exposure, RVs and their interactions via the following full model:

| (1) |

where β0, β1, and β2 (β2 = [β21…,β2q]T) are the coefficients of X,G, and S, g(⋅) is the logit link function, and μi = E(yi). The null hypothesis for the interaction test is H0 : β2k = 0 for k = 1,…,q, and the alternative hypothesis is H1: at least one element of β2 not equal to 0. The model under H0 or the null model is:

| (2) |

where μi is estimated in the GLMM framework under model (2) by treating covariate effects β0 as fixed effects and the genetic main effects β1 as independent random effects that share a common variance. Namely, β1 ~ N(0, τI) with I as a q × q identity matrix. The random effects approach has been used for modeling high-dimensional genetic variants.25,33 Based on model (2), we derive the asymptotic distribution of our score function. Briefly, let μ = [μ1, μ2,…,μn]T, the score function of the covariates UX = XT(y − μ), the score function of the interaction term US =ST(y −μ), and

with V = τGGT+ W−1 and W = diag(μ1(1 − μ1),…,μn(1 − μn)). By the central limit theorem and using Taylor expansion, it can be shown that

Variance parameters are estimated using the standard restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method. Details of the derivation are provided in Supplemental Materials Section A.1. Then we construct the aGE test based on the score function by defining

| (3) |

where γ ≥ 1 is a positive integer, and USk is the score function of the interaction term for the kth RV. The test statistic of GE(1) equals the test statistic of GE(2) equals which has a close relationship with rareGE. Although rareGE and GE(2) are derived from two different perspectives, both of them use GLMM to estimate the null model, thus rareGE and GE(2) have the same asymptotic distribution under the null, i.e., a mixture of chi-squared distribution.25 The test statistic of rareGE is calculated by taking derivatives of log-quasilikelihood expansion with respect to the variance component; however, the test statistic of GE(γ) is drawn from the derivative of the log of the marginal likelihood regarding β2 under model (1). Our aGE interaction test statistic is based on combining TGE(γ) by either taking the minimum of the p-values (minP) across Γ or using Fisher’s meta-analysis-like approach:

where TGE(γ) is the p-value of the GE(γ) test. The procedure for calculating the p-value for aGE is provided in Section 2.5. We search γ in the set of Γ = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} for both the aGE interaction and joint tests. We decided not to include infinity in Γ because it was found to lead to inflated type I error rates under certain scenarios.34

2.4. New method: aGE joint test

When both the genetic main effect and interaction effect exist, a joint test may have higher power than either the interaction effect test or the genetic main effect test alone.32 In addition, it is computationally simpler than the interaction test. The full model remains the same as in the interaction test (model (1)). The null model is

| (4) |

Accordingly, the null hypothesis for the joint test is H0 : β1 = β2 = 0 and the alternative hypothesis is H1 : at least one element of β1 or β2 is not 0. The corresponding score vector is UJGS = [G, S]T (y − μ) where μ is estimated through the MLE because the null model (4) no longer consists of the sparse and potentially large genotype matrix. Using derivations similar to those for the genetic main effect test,24 we conclude that

where

and

with V−1 = W = diag(μ1(1 − μ1), …, μn(1 − μn)). We separate the sum of the powered score test by the genetic main effect test and interaction effect test: let UJS = ST(y − μ) be the score vector of the interaction effects and UJG = GT(y − μ) be the score vector of the main effects. Since UJS and UJG can be on different scales, the aGE joint test statistic is combined on the p-value scale in the following two ways:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where and are the p-values for TJS and TJG, respectively.

2.5. P-value calculation

Since the minimum p-value and the combined p-value by Fisher’s method are no longer genuine p-values, we employ Monte Carlo simulation method to obtain the null distribution and calculate the p-values for the aGE interaction and joint tests. The specific steps for the interaction test are as follows.

(1) Estimate null model (2) by the GLMM and simulate for d = 1, 2, …D times;

(2) Calculate following equation (3);

(3) Calculate PaGE:

(3a) Calculate for each γ:

(3b) Calculate TaGE and :

(3c) Calculate PaGE :

The p-value of the joint test is calculated as follows.

(A) Estimate null model (4) by MLE and simulate and for d= 1, 2,…D times;

(B) Following steps (2) and (3a), calculate and (C) Calculate and following equation (5) and equation (6); then calculate PaGEjoint as in step (3c).

D is chosen to be 1,000 initially. It can be increased to a larger number when needed, for example, to achieve the genome-wide significance level in a real data application. Alternatively, the parametric bootstrap procedure can be used to calculate the p-value for the interaction test. Specifically, we fit null model (2) and obtain . Second, we simulate a new set of traits D times and fit null model (2) based on each set of simulated Yd to calculate the score function . Third, we follow steps (2)-(3) to calculate the corresponding p-values. Additionally, the parametric bootstrap and residual permutation are valid methods for obtaining p-values for the joint test. For the specific procedures, we refer to Pan et al.24 Since the parametric bootstrap requires fitting the null model multiple times, it is computationally intensive, especially for the interaction test. On the other hand, residual permutation, which requires fitting the data only once, can control the type I error rate for the joint test, not for the interaction test according to our preliminary simulation results (not shown). Therefore, we used Monte Carlo simulation method throughout as a unified and computationally efficient method. The accuracy of this method depends on the asymptotic distribution of the score function, for which we show its validity later.

2.6. Model the environmental main effect using splines

In many GxE applications, the environmental exposure is collected as a continuous variable, such as body mass index or pack-years of cigarette smoking in the application herein. Simple dichotomization of these continuous variables, e.g., as obese/non-obese and ever/never smokers, while allowing for parsimonious statistical modeling, may lose critical information in the exposure and thus lead to loss of power. On the other hand, it is known that inadequately modeling the main effect of a continuous exposure can result in inflated type I error rates in single-CV-based GxE testing.29–31 As to be illustrated in our simulations and real data application, misspecification of the environmental main effect in GxE testing not only leads to inflated type I error rates for the individual CV, but also for the RV set. Here, we propose to employ splines to allow for flexible modeling of the environmental main effect in the aGE test. Commonly used splines include cubic splines and linear splines. Given that the knot is known, the splines can be expressed as

where t represents the knot, usually set at the quantiles of the distribution of the environmental variable. e1(t) = E and R(ti, tj) can be regarded as residual terms.

We adopt a simple basis following Wahba and Gu for cubic splines:36,37 . We assume that the true model has a flexible form: logit(μi) = Xiβ01 + f(Ei)β02 + Giβ1 + Gig(Ei)β2, where Ei is centered to avoid an identifiability problem and g(Ei) can be of any functional form. The null hypothesis of interest is H0 : β2 = 0 for the interaction test and H0 : β1 = β2 = 0 for the joint test. For higher power, we use a working model with a parsimonious interaction term: . Type I error rate can be controlled for both the interaction test and joint test by using parsimonious modeling because if β2 = 0 then , and if β1 = β2 = 0 then . If g(E) is far from linear, then the power could be compromised at the cost of over-simplified modeling. We could further penalize R(ti, tj) to obtain smoother splines by assuming al ~ N(0,ϕ2I) and model with two random components under the null. However, we found that this approach could have an identifiability issue if G and E are dependent. Based on our preliminary experiments, we chose to fit splines with no penalization. We show later that overfitting the null model does not influence the power of the GxE test. In fact, He et al. modeled the continuous environmental variable using a similar nonparametric method (the method of “sieve”) in GxE analysis, but in the context of longitudinal CV-based analysis.38

3. Simulation Study

3.1. Simulation settings

We simulated case-control studies with case-control ratio 1:1. Genotypes were simulated as in Wang and Elston, with two linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks for each replication.39 The first block consisted of 8 causal RVs (csRVs). The second block was independent of the first block, consisting of different numbers of neutral RVs (0, 50, 100, 200). The RVs within each block had an AR1 correlation structure with ρ = 0.5. The MAF of RVs ranged from 0.1% to 5%. We also simulated three covariates: age ~ N(55, 5.72), sex ~ Bernoulli(0.5), and height ~ N(169, 9.42).

The type I error rate was evaluated by 10,000 replications with no GxE interactions. Simulated data followed the model below for evaluation of the type I error rate:

The genetic main effects had odds ratios (ORs) randomly drawn from a uniform distribution, i.e., . The four scenarios listed below were assessed for 3,500 cases and 3,500 controls.

Setting 1: E is correctly specified and G is independent of E (G ⊥ E): E ~N(0, 1), f(E) = 0.25E;

Setting 2: E is misspecified and G is independent of E (G ⊥ E): E ~ N(0, 1), f(E) = 0.25E + 0.5E2;

Setting 3: E is correctly specified and ;

Setting 4: E is misspecified and .

In addition, type I error rates for 500 cases and 500 controls were assessed under these four settings because the model performance relies on the asymptotic distribution of the score function for binary outcomes and our application example has a total sample size of 1,000. Additional simulation using a symmetric main effect distribution was performed for the interaction test in setting 1 to evaluate the performance of different estimation methods, i.e., GLMM vs ridge regression.

Power for the interaction tests was analyzed under setting 1 and setting 2 for 1,000 replications. The model for power evaluation was

| (7) |

We evaluated the power when the interaction effects were in different directions by setting OR2 = exp(β2) and exp(β2) = [exp(β21), …, exp(β28)]T = [3, 1/3, 3, 3, 2, 1/3, 1/3, 1/2]T and in the same direction by drawing and then taking absolute value of β2k.

Power for the joint tests was evaluated under the same model as that for the interaction tests. The interaction effects were held across all the scenarios, i.e., , while the magnitude of the genetic main effect sizes varied, i.e., no main effects (all β1k equal to 0), moderate main effects , or strong main effects . Similarly, 3,500 cases and 3,500 controls were simulated for each replication. We further examined the power of strong main effects for 500 cases/controls and 5,000 cases/controls in Supplementary Materials A.2.1.

We considered rareGE interaction and joint, iSKAT, aGE interaction and joint tests, as well as the multivariate score test for joint effects, in the comparison. We used cubic splines to model the environmental variable for the aGE tests under different settings, denoted as ⋅sp, such as aGEsp and aGEjointsp. Without subscript sp, the tests assumed a linear relationship. Moreover, we denoted ⋅true as the tests using the correct functional form of the environmental variable. Throughout the simulation study, we fixed the test significance level at α = 0.05.

3.2. Results of the simulation study

3.2.1. Type I error rate

Table 1 shows the type I error rates for the interaction tests and joint tests under the four different settings. For simplicity, we only show the aGE tests using Fisher’s method to combine p-values. Both minP and Fisher’s approach of combining p-values had correct type I error rates. The p-values of the two combination methods were close when no neutral RV was presented; therefore, our conclusion remained qualitatively the same using either method. All tests (aGE, rareGE, and iSKAT) maintained the type I error rates well when the model was correctly specified with a sample size of 7,000. When the environmental main effect was misspecified, all set-based tests with oversimplified modeling of the environmental variable suffered from inflated type I error rates. Furthermore, the gene-environment dependence considerably deteriorated such inflation. This inflation was mitigated after using the cubic splines to handle the nonlinear effect. When the sample size decreased to 1,000, the type I error rates for aGE and rareGE were still under control, but iSKAT had a slight inflation (empirical type I error rate was 0.061 with 10,000 replications). It also turned out that iSKAT was sensitive to the inclusion of neutral variants. With 200 neutral RVs included in the set and a sample size of 7,000, the empirical type I error rate was 0.083. Therefore, we did not include iSKAT for power comparison in the following sections. Last, the conclusion remained the same when the genetic main effects (β1) followed a symmetric normal distribution (result not shown). In summary, the maintenance of the type I error rate depends on the sample size, number of RVs, and correct model specification. All the tests under consideration were hardly sensitive to the skewness of the distribution of the genetic main effects under our simulation settings.

Table 1.

Empirical type I error rates at the significance level 0.05 when no neutral RV was included. aGEsp: aGE interaction test that uses cubic splines to model the environmental main effect; aGEjointsp: aGE joint test that uses cubic splines to model the environmental main effect; G ⊥ E: genetic risk factors and environmental variable are independent; : genetic risk factors and environmental variable are not independent; f(E): the true functional form of the environmental main effect. Inflated type I error rates are in boldface.

| Setting | Interaction test | Joint test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aGE | aGEsp | rareGE | iSKAT | aGEjoint | aGEjointsp | rareGEjoint | |

| 3,500 cases and 3,500 controls | |||||||

| G⊥E,f(E) ∝ E | 0.048 | 0.050 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.046 | 0.048 | 0.047 |

| G⊥E,f(E) ∝ E2 | 0.080 | 0.053 | 0.098 | 0.113 | 0.070 | 0.052 | 0.077 |

| ,f(E) ∝ E | 0.054 | 0.044 | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.047 | 0.049 | 0.047 |

| , f (E) ∝ E2 | 1 | 0.046 | 1 | 1 | 0.930 | 0.049 | 0.933 |

| 500 cases and 500 controls | |||||||

| G⊥E,f(E) ∝ E | 0.048 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.061 | 0.047 | 0.050 | 0.047 |

| G⊥E,f(E) ∝ E2 | 0.067 | 0.053 | 0.078 | 0.101 | 0.058 | 0.048 | 0.064 |

| ,f(E) ∝ E | 0.044 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.059 | 0.051 | 0.052 | 0.046 |

| , f (E) ∝ E2 | 0.666 | 0.046 | 0.659 | 0.885 | 0.741 | 0.056 | 0.700 |

3.2.2. Power

Interaction tests:

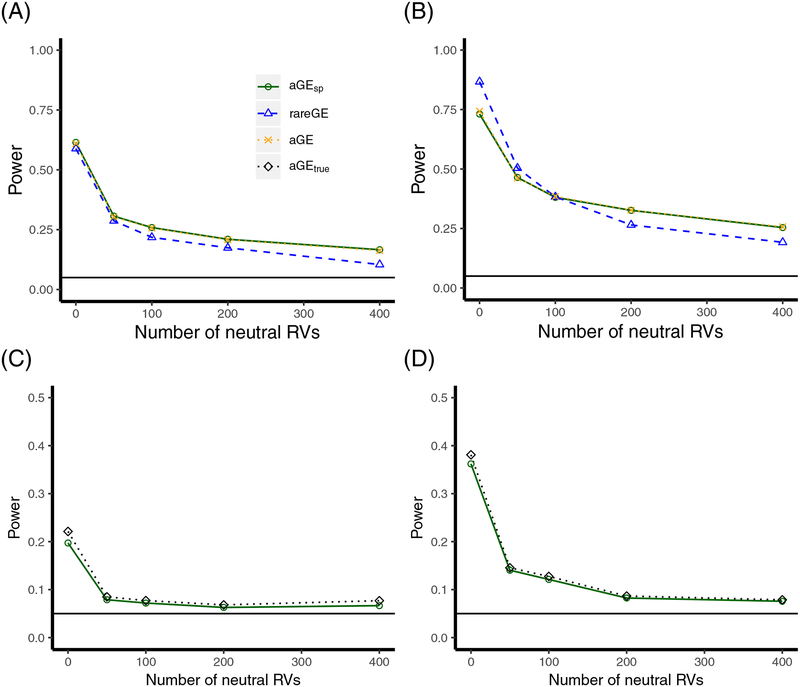

Fig 1 shows that the aGE interaction test outperformed the other tests in the presence of neutral RVs: for example, with 200 neutral RVs and interaction effects having different directions in Fig 1B, the power of the aGE test was 0.326 under setting 1, which was higher than that of the rareGE (0.265). In general, the power of the interaction test decreased as the number of neutral RVs increased; however, the rate of power loss was different. The aGE test that combines a broad set of tests, including but beyond the GE(2) test, was more flexible and adaptive. When all the variants in the set were causal and the effects were in different directions, rareGE showed better performance than the aGE test because of the trade-off between model adaptivity and power. When all the variants were causal and the effects were in the same direction, the aGE test has slightly better performance than rareGE because GE(1) propelled the power.

Figure 1.

Empirical power curves for interaction tests with increasing numbers of neutral variants. (aGEsp: aGE with cubic splines modeling environmental main effect; aGEtrue: aGE testing linear GxE based on using the correct linear or quadratic function to fit the environmental main effect. A: f(E ∝ E and β2’s are in the same direction; B: f(E) ∝ E and β2’s are in different directions; C: f(E) ∝ E2 and β2’s are in the same direction; D. f(E) ∝ E2 and β2’s are in different directions. G and E are independent in panels A to D.)

With increasing numbers of neutral RVs, GE(γ) with higher power γ became more powerful and aGE always approached the most powerful GE(γ) test in the family. Therefore, the most powerful GE test could be different from GE(1) and GE(2), and aGE gained power from a higher-order GE(γ) test. As expected, odd γ performed better when the interaction effects (β2) were in the same direction, while even γ performed better when the β2’s had different directions. However, we found that γ with the highest power depended more on the number of neutral variants than the direction of the effects of the causal RVs. Table 2 shows that GE(4) and GE(6) had the highest power when the number of neutral RVs was more than 50, regardless of the direction of the interaction effects. This indicates that the noise level played a bigger role in deciding the γ with the highest power and Γ = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} suffices in a wide range of scenarios where the number of neutral variants could be as large as 400. We also observed that Fisher’s method was slightly more powerful than the minP method when the number of neutral RVs was large, while the minP method was more powerful than Fisher’s method when the number of neutral RVs was small. Furthermore, Table 2 shows that the p-values of GE(1) and GE(2) were close to those based on asymptotic distributions. Therefore, we are assured of the validity of using Monte Carlo simulation method to calculate the p-values. We also demonstrated the effectiveness of using cubic splines to saturate the environmental main effect model: the power of the saturated main effect model was almost as high as that obtained when using the correct function of the main effect model (Fig 1). For example, in setting 2 with no neutral variant, the saturated model had an empirical power of 0.362, whereas the empirical power for the correct model specification was 0.381. In Supplemental Materials Section A.2.2, we demonstrate numerically that the power loss when using splines was minor with more scenarios considered, including when G and E were dependent.

Table 2.

Empirical power for interaction tests under setting 1 with no neutral variant (3,500 cases and 3,500 controls). The most powerful GE test in the GE(γ) family is in boldface. β2’s are the coefficients of the interaction effects; aymGE(1) is GE(1) based on asymptotic null distribution; aymGE(2) is GE(2) based on asymptotic null distribution, i.e., mixture of chi-squared distributions.

| Tests | β2 in the same direction | β2 in different directions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 0 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | |

| GE(1) | 0.750 | 0.191 | 0.131 | 0.088 | 0.059 | 0.306 | 0.104 | 0.067 | 0.056 | 0.053 |

| GE(2) | 0.584 | 0.284 | 0.217 | 0.165 | 0.094 | 0.867 | 0.504 | 0.377 | 0.251 | 0.171 |

| GE(3) | 0.604 | 0.296 | 0.227 | 0.154 | 0.091 | 0.601 | 0.325 | 0.250 | 0.215 | 0.149 |

| GE(4) | 0.509 | 0.281 | 0.255 | 0.201 | 0.147 | 0.797 | 0.509 | 0.412 | 0.354 | 0.265 |

| GE(5) | 0.505 | 0.267 | 0.235 | 0.176 | 0.132 | 0.653 | 0.378 | 0.333 | 0.301 | 0.231 |

| GE(6) | 0.480 | 0.263 | 0.247 | 0.200 | 0.158 | 0.747 | 0.470 | 0.387 | 0.342 | 0.272 |

| aGE | 0.686 | 0.298 | 0.237 | 0.193 | 0.124 | 0.806 | 0.457 | 0.349 | 0.293 | 0.231 |

| aGEFisher | 0.610 | 0.304 | 0.257 | 0.208 | 0.163 | 0.743 | 0.462 | 0.385 | 0.327 | 0.257 |

| aymGE(1) | 0.752 | 0.196 | 0.136 | 0.086 | 0.059 | 0.308 | 0.104 | 0.069 | 0.060 | 0.055 |

| aymGE(2) | 0.593 | 0.290 | 0.222 | 0.171 | 0.096 | 0.865 | 0.509 | 0.379 | 0.251 | 0.181 |

Joint tests:

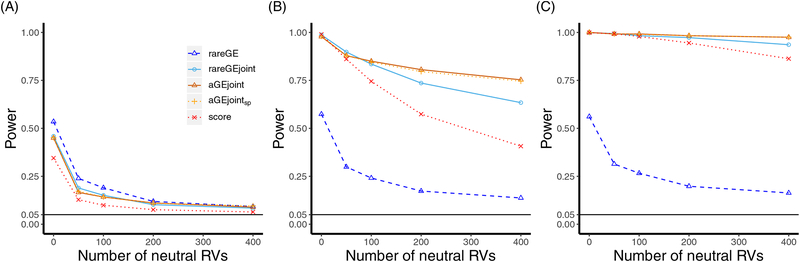

The findings of the joint tests were similar to those of the interaction tests. We observed that the rareGE joint test had inflated type I error rates when the model was not correctly specified (Table 1). However, the aGEjointsp test controlled the type I error rates and maintained high power, as shown in Fig 2. We further showed that the rareGE joint test was powerful at different relative scales of the ratios of the main-interaction effects. While our proposed aGE joint test was as powerful as the rareGE joint test when there was no neutral variant, it became more powerful than the latter test when the number of neutral RVs was large, as shown in Table 3. Compared to the rareGE and aGE joint tests, the multivariate score test lost a large amount of power as the number of neutral RVs increased. In addition, the power of the joint tests was as high as that of the interaction tests when the genetic main effects were absent, but it was much higher when the genetic main effects were moderate or strong.

Figure 2.

Empirical power curves for joint tests with increasing numbers of neutral RVs. aGEjointsp: aGE joint test that uses cubic splines to model the environmental main effect. A: no main effects: all genetic main effects (β1k equal to 0); B: moderate main effects: ; C: strong main effects: .

Table 3.

Empirical power for joint tests with 200 neutral variants and (3,500 cases and 3,500 controls). aGEjointsp: aGE joint test that uses cubic splines to model the environmental main effect; OR1k = exp(β1k) is the odds ratio of the genetic main effect for the kth RV. The most powerful test is in boldface.

| Setting | rareGE | rareGEjoint | aGEjoint | aGEjointsp | score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1 = 0 | 0.119 | 0.102 | 0.111 | 0.109 | 0.076 |

| 0.173 | 0.736 | 0.806 | 0.796 | 0.574 | |

| 0.198 | 0.973 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.945 |

4. Real Data Example: Pathway-by-smoking Interaction Analysis for Pancreatic Cancer

We further applied our proposed aGE tests, together with rareGE and iSKAT, to the data from a case-control study of pancreatic cancer based at MD Anderson Cancer Center as part of the Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (PanC4).40 Cases were defined as patients diagnosed with primary adenocarcinoma of the pancreas; controls were matched to cases according to birth year, sex and self-reported race, and were free of pancreatic cancer at the time of recruitment. Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA.41 Smoking is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Pathway analysis has shown promise in providing biological insights into disease mechanisms. Previous GxE analysis of GWAS data found that genes that interact with smoking showed enrichment in the axonal guidance signaling pathway and the α-adrenergic signaling pathway.42 Along the same line, we investigated the biological pathway-by-smoking interaction for pancreatic cancer with a focus on RVs measured using the Illumina Exome Chip array.43 Pack-years of cigarette smoking as our continuous environmental variable, defined as the number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years the person has smoked, is more informative than binary variables, e.g., former/current smoker. As shown in Supplemental Materials Figure S4, pack-years of cigarette smoking had a nonlinear relationship with the logit of the probability of having pancreatic cancer. This nonlinearity would lead to model misspecification if not adequately taken into account, such as simply modeled as a linear function. As covariates, our GxE models also included age (continuous), sex, the top five principal components capturing the population substructure, and categorized body mass index. Genotype data were obtained as part of the PanC4 ExomeChip project.43 The quality control steps included removing RVs with missing rate greater than 2%, or deviating from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P < 10−6). Individuals with identity by stated coefficient larger than 0.25 or with missing RV rate greater than 2% were further removed, resulting in 613 cases and 498 controls. RVs (MAF less than 5%) with at least two minor alleles in the sample population were grouped into pathways according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).44 We identified 197 KEGG pathways with the number of RVs ranging from 3 to 1,105 (mean = 173, median=119, standard deviation = 173), and the cumulative minor allele count (cMAC) ranging from 57 to 17,173 (mean = 2,622, median=1,840, standard deviation = 2,631). Detailed definitions of the 197 KEGG pathways were previously provided.45

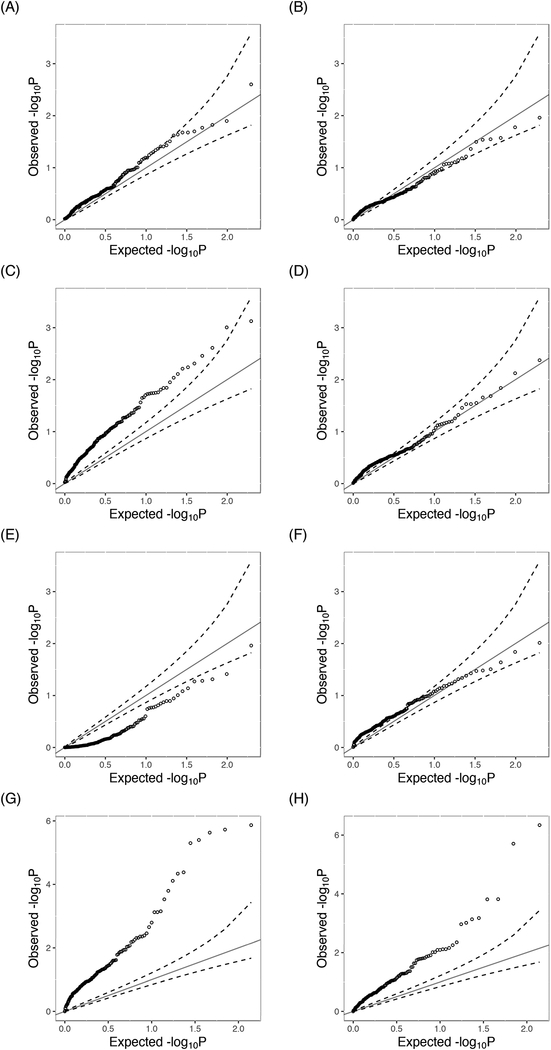

The QQ plots of the p-values were severely inflated for tests that linearly modeled pack-years of cigarette smoking, including rareGE, iSKAT and rareGE joint tests (Fig (3)). Tests that used splines to model the environmental main effect had much better performance in controlling the inflation. Consistent with our simulation results, iSKAT had an inflated type I error rate even after correcting the model misspecification for the environmental variable, indicating that iSKAT requires a larger sample size for its asymptotic property to be held and is less robust to the presence of a large number of RVs. In this study, none of the pathways reached genome-wide significance based on the Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/197 = 0.00025) due to the moderate sample size and thus lack of power. However, we found one particular pathway (hsa03020) related to RNA polymerase that showed nominal significance with aGEsp p-value = 0.0020, which was also previously reported by a CV-based pathway-by-smoking analysis of pancreatic cancer with a much larger sample size.42 This pathway consisted of 35 RVs with a cMAC of 360. Interestingly, rareGEsp and rareGEjointsp tests had p-values larger than 0.05, and GEsp(1) was the main driver of the small p-value within the GE(γ) family, thus shedding light on the underlying genetic architecture. Since this pathway is related to gene transcription regulation, further replication is warranted to confirm this observation with a larger sample size. We report 11 additional pathways that interacted with smoking at a nominal level (p-value ≤ 0.05) in Supplemental Materials Table S3. Nine of the top 12 pathways had smaller aGEsp p-values than that of aGEjointsp, demonstrating the importance of interaction tests in finding novel pathways and understanding the biological mechanism of complex diseases.

Figure 3.

QQ plots for pathway-by-pack-years interaction for pancreatic cancer. Subscript ⋅sp: splines were used to fit the environmental main effect; A. aGEsp: genomic control γ = 0.97; B. aGEjointsp: λ = 0.85; C.rareGE: λ = 1.59; D.rareGEsp: λ = 0.99; E. rareGEjoint: λ = 0.66; F. rareGEjointsp: λ = 0.92; G. iSKAT: λ = 3.69; H. iSKATsp: λ = 2.92.

5. Discussion

We have proposed a family of powerful and data-adaptive GxE tests for RV, called aGE, which maintains high power across varying GxE interaction patterns and in the presence of a large number of neutral RVs. Using simulations and a real data application, we have demonstrated that RV-based GxE tests can be prone to inflated type I error rates due to either poor estimation of the genetic main effects under the null hypothesis of no GxE effects or model misspecification for the environmental main effect. We tackled the former problem by using the GLMM to estimate the genetic main effects of RVs while addressing the latter challenge by saturating the model for the environmental main effect using splines. As a result, the proposed aGE test can maintain high power without inflating the type I error rate.

A noticeable feature of the aGE test is that it is more resilient to power loss due to an increasing numbers of neutral RVs in a test set, and thus decreasing signal-to-noise ratio, than existing RV-based GxE tests such as rareGE. This is an appealing property for NGS-based GxE analysis. In fact, while whole-exome/genome sequencing technology allows for genotyping genetic variants at the single-base resolution, it also generates more RVs as the sample size increases. For example, in the UK10K project, whole-genome sequencing of 3,781 individuals resulted in 42 million genetic variants, more than half of which were singletons or doubles, i.e., RVs that were only observed once or twice in the entire sample.46 Therefore, the abundance of RVs has become the norm in large-scale NGS-based genetic epidemiology consortia, such as the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program that has already generated whole-genome sequencing data in more than 100,000 individuals.47 Our proposed aGE test is thus uniquely positioned and well suited for GxE analysis in these large research consortia.

Due to the low MAFs of multiple RVs in a set, a unique challenge with RV-set-based GxE tests is the need to estimate the genetic main effects under the null model of no GxE effects. In the proposed aGE test, we have employed the GLMM to estimate the null model by assuming the genetic main effects as random effects and found it works well in our extensive simulations and real data application. On the other hand, iSKAT uses generalized cross-validation-based ridge regression to penalize the genetic main effects in a similar manner as GLMM; however, we found it to be more prone to inflated type I error rates and non-convergence when the sample size was relatively small or a large number of neutral RVs were present. Therefore, to estimate the main effects for RVs, we recommend using mixed model methods, i.e., GLMM, for binary phenotypes and a linear mixed model for continuous outcomes. It is natural to extend the current model in the mixed model framework by including additional random components to account for the relatedness or population stratification among individuals in family-based studies, for example, the Framingham Heart Study in the TOPMed program; see Chen et al. for a review of related methods for the genetic main effect tests.48 As for computational speed, aGE uses Monte Carlo simulation method to obtain the null distribution of the test statistics. It is much faster than the parametric bootstrap procedure because it involves fitting the null model only once. A drawback of Monte Carlo simulation method is that its accuracy relies on the asymptotic convergence rate. In our simulation studies and real data application, a total sample size of 1,000 appeared to suffice for aGE and rareGE.

We observed that joint tests were relatively more robust to misspecification of the main effect than interaction tests. The interaction tests suffer from potential bias in the estimation of both the genetic main effects and the environmental main effect, whereas the joint tests only suffer from bias in the latter estimation. In addition to robustness, the power of joint tests was comparable or higher than that of the interaction tests when the genetic main effects were merely moderate. Furthermore, joint tests are usually faster in estimation than interaction tests because the genetic main effects are absent under the null model of the former. Therefore, for the purpose of finding novel genes, joint tests are recommended due to their robustness, high power, and fast computational speed. The interaction tests can serve as a complementary analytic tool. If the study objective is to find genetic variants that modify the effect of an environmental exposure on disease risk and to understand the biological mechanism underlying a complex disease, then our proposed aGE interaction test is powerful and versatile for searching for such RVs. The aGE test was mainly developed for RVs; however, as a complementary analysis to individual SNP-based tests, it can also be used for CVs, for which the existence of high linkage disequilibrium may be problematic for the MLE. We provide simulation results for CVs in Supplemental Materials Section A.2.3.

With the completion of large-scale functional genomic projects, such as ENCODE,49 Roadmap Epigenomic,50 and GTEx projects,51 biological functional annotations of RVs have become available and have been incorporated as external weights in statistical tests for main effects as well as GxE interactions.52–54 Although we did not consider functional annotations in the proposed aGE test, in principle they can be incorporated as external weights in the score function, which could further improve the power and warrants future investigation. We have implemented our proposed tests in an R package, “aGE”, available at https://github.com/ytzhong/projects/.

Supplementary Material

6. Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01CA169122; P.W. was supported by NIH grants R01HL116720 and R21HL126032; H.C. was supported by NIH grants R00HL130593 and U01HL120393. The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their many helpful and constructive comments that improved the presentation of the paper. The authors thank Ms. Lee Ann Chastain for editorial assistance. The authors acknowledge the Texas Advanced Computing Center at The University of Texas at Austin for providing HPC resources that contributed to the research results reported within this paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zuk O, Hechter E, Sunyaev SR, et al. The mystery of missing heritability: Genetic interactions create phantom heritability. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(4): 1193–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson G. Rare and common variants: twenty arguments.Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(2):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, ]et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461(7265):747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C, Kraft P, Zhai K, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese identify multiple susceptibility loci and gene-environment interactions.Nat Genet. 2012;44(10):1090–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hancock D, Artigas MS, Gharib S, et al. Genome-Wide Joint Meta-Analysis of SNP and SNP-by-Smoking Interaction Identifies Novel Loci for Pulmonary Function. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(12):e1003098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritz BR, Chatterjee N, Garcia-Closas M, et al. Lessons learned from past gene-environment interaction successes. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(7):778–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutter CM, Mechanic LE, Chatterjee N, Kraft P, Gillanders EM. Gene-environment interactions in cancer epidemiology: a National Cancer Institute Think Tank report. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(7):643–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Ren J. ALDH2 in alcoholic heart diseases: molecular mechanism and clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132(1):86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming SM. Mechanisms of Gene-Environment Interactions in Parkinson’s Disease.Curr Environ Health Rep. 2017;4(2):192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carreón T, Ruder AM, Schulte PA, et al. NAT2 slow acetylation and bladder cancer in workers exposed to benzidine. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(1):161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolock SL, Yates A, Petrill SA, et al. Gene × smoking interactions on human brain gene expression: finding common mechanisms in adolescents and adults J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(10):1109–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6(3):e1000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuo K, Hamajima N, Shinoda M, et al. Gene–environment interaction between an aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) polymorphism and alcohol consumption for the risk of esophageal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(6):913–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano K, Yamamoto E, Aya K, et al. Genome-wide association study using whole-genome sequencing rapidly identifies new genes influencing agronomic traits in rice. Nat Genet. 2016;48(8):927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen JC, Pertsemlidis A, Fahmi S, et al. Multiple rare variants in NPC1L1 associated with reduced sterol absorption and plasma low-density lipoprotein levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(6):1810–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014;508(7497):469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auer PL, Teumer A, Schick U, et al. Rare and low-frequency coding variants in CXCR2 and other genes are associated with hematological traits. Nat Genet. 2014;46(6):629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asimit JL, Day-Williams AG, Morris AP, Zeggini E. ARIEL and AMELIA: testing for an accumulation of rare variants using next-generation sequencing data. Hum Hered. 2012;73(2):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgenthaler S, Thilly WG. A strategy to discover genes that carry multi-allelic or mono-allelic risk for common diseases: a cohort allelic sums test (CAST).Mutat Res. 2007;615(1–2):28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X. Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(1):82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan W Asymptotic tests of association with multiple SNPs in linkage disequilibrium. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33(6):497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neale BM, Rivas MA, Voight BF, et al. Testing for an unusual distribution of rare variants. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(3):e1001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Lin X. Rare-variant association analysis: study designs and statistical tests. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95(1):5–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan W, Kim J, Zhang Y, Shen X & Wei P. A powerful and adaptive association test for rare variants. Genetics. 2014; 197: 1081–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Meigs JB, Dupuis J. Incorporating gene-environment interaction in testing for association with rare genetic variants. Hum Hered. 2014;78(2):81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin X, Lee S, Christiani DC, Lin X. Test for interactions between a genetic marker set and environment in generalized linear models. Biostatistics. 2013;14(4):667–681.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin X, Lee S, Wu MC, et al. Test for rare variants by environment interactions in sequencing association studies. Biometrics. 2016;72(1):156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coombes B, and Basu S and McGue M. A combination test for detection of gene-environment interaction in cohort studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2017;41(5):396–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voorman A, Lumley T, McKnight B, Rice K. Behavior of QQ-plots and genomic control in studies of gene-environment interaction. PloS One. 2011;6(5):e19416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Kraft P. On the Robustness of Tests of Genetic Associations Incorporating Gene-environment Interaction When the Environmental Exposure is Misspecified. Epidemiology. 2011;22(2):257–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornelis MC, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Liang L, et al. Gene-environment interactions in genome-wide association studies: a comparative study of tests applied to empirical studies of type 2 diabetes. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;175(3):191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraft P, Yen Y, Stram DO, Morrison J, Gauderman WJ. Exploiting Gene-Environment Interaction to Detect Genetic Associations. Hum Hered. 2007;63(2):111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: A Tool for Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei P, Cao Y, Zhang Y, et al. On Robust Association Testing for Quantitative Traits and Rare Variants. G3-Genes Genom Genet. 2016;6(12):3941–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davison AC, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge university press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahba G Spline models for observational data. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu C Smoothing spline ANOVA models. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Z, Zhang M, Lee S, et al. Set-Based Tests for the Gene–Environment Interaction in Longitudinal Studies. J Am Stat Assoc. 2017;112(519):966–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang T, Elston RC. Improved Power by Use of a Weighted Score Test for Linkage Disequilibrium Mapping.Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(2):353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amundadottir L, Kraft P, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41(9):986–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2014, featuring survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang H, Wei P, Duell EJ, et al. Axonal guidance signaling pathway interacting with smoking in modifying the risk of pancreatic cancer: a gene-and pathway-based interaction analysis of GWAS data. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(5):1039–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Childs EJ, Mocci E, Campa D, et al. Common variation at 2p13. 3, 3q29, 7p13 and 17q25. 1 associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47(8):911–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(suppl1):D355–D360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei P, Tang H, Li D. Insights into pancreatic cancer etiology from pathway analysis of genome-wide association study data. PloS One. 2012;7(10):e46887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.UK10K Consortium. The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature. 2015;526(7571):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brody JA, Morrison AC, Bis JC, et al. Analysis commons, a team approach to discovery in a big-data environment for genetic epidemiology. Nat Genet. 2017;49(11):1560–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen H, Malzahn D, Balliu B, Li C, Bailey JN. Testing genetic association with rare and common variants in family data. Genet Epidemiol. 2014. September 1;38(S1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ENCODE Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414), 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roadmap Epigenomics. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518(7539), 317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.GTEx Consortium. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550(7675), 204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim T, Wei P. Incorporating ENCODE information into association analysis of whole genome sequencing data. BMC Proc. 2016;10(Suppl 7):257–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrison AC, Huang Z, Yu B, et al. Practical approaches for whole-genome sequence analysis of heart-and blood-related traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(2):205–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su YR, Di CZ, Hsu L. A unified powerful set-based test for sequencing data analysis of GxE interactions. Biostatistics. 2017;18(1):119–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.