Abstract

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) promise to advance a number of real-world technologies. Of these applications, they are a particularly attractive for uses in chemical sensors for environmental and health monitoring. However, chemical sensors based on CNTs are often lacking in selectivity and the elucidation of their sensing mechanisms remains challenging. This review is a comprehensive description of the parameters that give rise to the sensing capabilities of CNT-based sensors and the application of CNT-based devices in chemical sensing. This Review begins with the discussion of the sensing mechanisms in CNT-based devices, the chemical methods of CNT functionalization, architectures of sensors, performance parameters, and theoretical models used to describe CNT-sensors. It then discusses the expansive applications of CNT-based sensors to multiple areas including environmental monitoring, food and agriculture applications, biological sensors, and national security. The discussion of each analyte focuses on the strategies used to impart selectivity and the molecular interactions between the selector and the analyte. Finally, the Review concludes with a brief outlook over future developments in the field of chemical sensors and their prospects for commercialization.

Keywords: sensors, carbon nanotubes

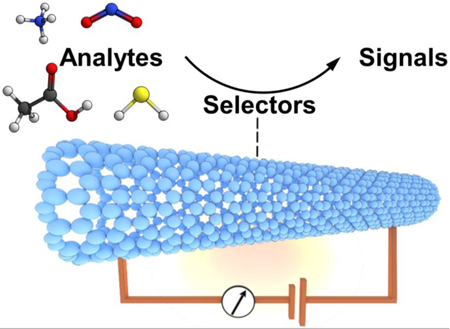

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction and Scope

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have now been a subject of research for more than 20 years. Mirroring this academic endeavor is the worldwide commercial interest, leading to the production capacity of several thousand tons of CNTs per year.1 These developments have paved ways to the wide array of emerging applications2,3 in microelectronics,4,5 computing,6 medicinal therapy,7 electrochemical biosensors,8 and chemical sensors.9,10 However, the field is far from mature and our understanding of the chemical and physical properties of these materials continues to grow. At the outset, it is fair to state that the chemistry of CNTs remains dubious and often imprecise.11 Although advances in the production have allowed preferential synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNTs) with metallic or semiconducting properties with selectivity of 90 to 95%,12,13 production of pure semiconducting tubes remains cost-prohibitive. Commercial supplies of SWCNTs, despite improvements in consistency, are still polydisperse in length, diameter, and chirality. Separations methods by density-gradient centrifugation with selective surfactants,14 conjugated polymer wrappings,15,16 or by gel chromatography17,18 are not readily scaled. Bottom-up syntheses have seen heroic efforts,19 but remain far from full realization. Similarly, multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) can be produced in high volume through large-scale chemical vapor deposition (CVD), however they suffer from structural deviations, contaminations, and impurities that often require costly treatment for removal.

One may ask why CNTs continue to garner such attention, given the complexity and what some chemists may even refer to as impurities. Clearly, scientific curiosity is one answer. The other motivation driving CNT research is their unusual optical, electrical, mechanical, and chemical properties. CNTs are unique organic electronic wires with shape persistence. These π-electron wires, possessing quantized electronic states with coherence lengths that are longer than what is possible for conducting polymers, making them ideal building blocks for nanoelectronic devices. Furthermore, CNTs can be organized in nanowire networks and with the addition of recognition elements are ideal for sensing applications. Indeed, it was understood from the early 1990s that molecular and nanowire architectures could produce sensors with superior sensitivity, benefitting from the restricted transport along percolative paths and the large surface area-to-volume ratio.20 Hence, these principles were translated quickly to create the first example of SWCNT chemical sensors by Dai and coworkers.21 The authors strived to realize the concept of nanowire in its purest form by connecting electrodes with an individual SWCNT to observe the change in its conductivity when exposed to oxidative p-doping (NO2) and reductive un-doping (NH3) gases. This study is certainly historic in the field of SWCNTs. However, similar to the onset of every area, much more progress was required to usher CNT platforms into versatile and useful sensors.

It is indisputable that selectivity underpins the utility of any chemical sensor. Of course, sensitivity and stability must be given the appropriate weight as discussed in the later sections of this review. The advancements in system integrations and electrical interfaces have lowered the stringent requirements of these latter parameters. For examples, electrical signals can be isolated and amplified, and trace analytes can be captured and released using pre-concentrators. However, without selectivity, the sensors are often rendered ineffective as a result of confounding effects in real-world environments such as interfering species, varying humidity, and fluctuation in temperature. Specificity, or perfect selectivity, is often not needed; and, robust sensors can be created from arrays of sensing elements, with each sensor having limited discriminating ability.22 Array-based sensors, such as a CNT-based chemical nose/tongue, are applicable to most types of chemical sensing and continue to progress toward the idea of a “universal sensor.” Inspired by the biological olfactory system, each individual channel in the sensor array needs not be perfectly orthogonal to every other channel. On the contrary, unique “fingerprint” corresponding to each analyte or group of analytes can arise when each channel of an array responds to several analytes in varying degrees. Nevertheless, it is seldom a disadvantage to incorporate sensors that are inherently selective to the target analytes. And indeed, a combinatorial approach of several highly selective and cross-selective sensing channels might lead to an optimized performance of the sensor array. SWCNTs are natural sensing materials as their transport properties are extremely responsive to their environment. They have suffered from limitation in selectivity at the inception of this field. Indeed, this limitation contributed to the relatively few commercial CNT-based sensors in spite of a massive world-wide research effort.

As a result, this review will place significant emphasis on the ways in which chemical science and engineering can be applied to create CNT-based sensors exhibiting selective responses to target analytes. Such approaches predominantly include functionalization with selectors (e.g., polymer-wrapping and sidewall attachments). Quite often, the sensing performance of CNTs depends not only on the molecular recognition, but also on the response of the collective system, which can be affected by non-specific chemical, thermal, and mechanical interactions. As will be discussed, the mechanism of chemical sensing may likely be intra-CNT and inter-CNT in nature; however, the other interfaces (CNT-electrodes and CNT-dielectric) must also be considered. In functionalization of SWCNTs, it was proposed initially that noncovalent attachments were preferred, as a result of the simplicity of the technique and the small perturbation on the base transport properties of the SWCNTs. Early applications of these methods to immobilized proteins appeared to give excellent performing biosensors.23 However, detailed follow-up studies by the same researchers later revealed that the interfaces between the metal electrodes and the CNTs were non-innocent, and the interactions at these locations constitute the major responses for these sensors.24 Hence, if the primary response occurs at locations other than sites comprising receptors/selectors, the sensor will lack predictably selective responses. In surveying the literature on chemical sensors, it is imperative to be properly skeptical regarding the advertised selectivity. Indeed, we will call out some of the results presented in this review when there is no apparent chemical rationale for the anticipated selectivity.

Although the nano-carbon area presents considerable diversity for chemical sensors, this review will strictly focus on electrical transduction using CNTs. The majority of nano-carbon sensors are based upon SWCNTs. Semiconducting CNTs are highly sensitive to carrier pinning and populations (i.e. doping levels). These are finite conductive pathways through the nanowire networks and perturbing such pathways increases the tortuosity for charge transport from one electrode to the other (i.e. resistivity). In addition to electrical transport, semiconducting SWCNTs are emissive. Similar to the concepts developed around semiconducting molecular wires,25 transport of excitons in SWCNTs can provide signal gain and emissions at long wavelengths for in vivo applications.26 This area is promising, and we direct interested readers to a review by Strano and coworkers.27 Although, there is ongoing interest in graphene-based sensors,28,29 the metallic state of these 2D materials is harder to quench or enhance, allowing carriers migration around perturbed regions. MWCNTs provide the wire architecture, however the inner tubes in these structures are prevented from interacting with the surrounding chemical environment. As a result, the intra-CNT mechanisms are not operative because the carriers can migrate through the unperturbed pathways of the inner core. Nevertheless, with suitable modulation of the inter-MWCNT transport, these materials can constitute effective sensors.

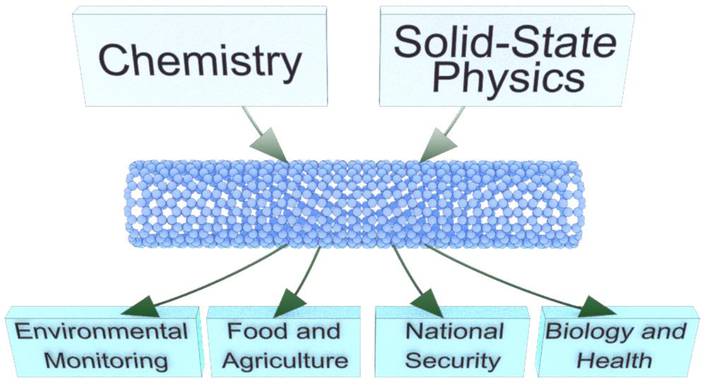

It is our intent to provide the reader a comprehensive perspective on the field of electrically-read CNT-based sensors. However, there have been previous reviews that have covered aspects of this field that may complement some of our descriptions.2,9,10,30–35 This article is conceptually self-contained and intended to serve as an informational resource to both newcomer and experienced researchers in the area of CNT-based sensors. As a result, we will cover some contributions that were highlighted in previous reviews. For researchers working in the sensor area, it is natural to think about real-world applications. It is also our perspective that these materials will become a significant commercial sensor platform in the near future. As a result, after introducing the concepts, we have organized the coverage of the literature by the respective application areas as shown in Figure 1. This approach is also intended to assist researchers with interests in the use of the sensors who are not sensor developers themselves.

Figure 1.

Schematic highlighting the application fields of the CNT-based chemical sensors covered in this review.

1.1. Chemical Sensing Mechanisms

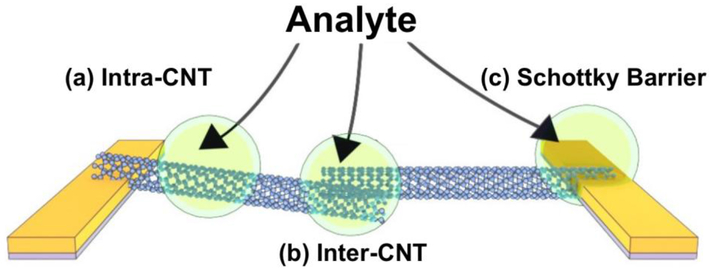

The discussion on the exact mechanisms that cause the response of carbon nanotube-based sensors is very much alive. In contrast to conducting polymers, whose behavior can be described via molecular mechanisms, the properties of CNTs need to be described beyond local molecular structures, as is done in solid state physics. As a result of their extended π-system, the frontier orbitals of CNTs are best described through band structures rather than discrete molecular orbitals. Accordingly, chemical intuition is often not sufficient when trying to predict or describe CNT-based sensing mechanisms. In this section, we will discuss several mechanisms that give rise to signals in CNT-based chemical sensors of different architectures and functionalization techniques. Responses of CNT-based sensors are attributed to effects arising within the tubes (intra-CNT), effects arising at contact points between tubes (inter-CNT), or effects due to the contact between the tubes and the electrodes (Schottky barrier modulations) (Figure 2). The strength of these different mechanisms can depend strongly on the analyte, the defect concentrations in the CNTs, and the device architecture. For a historical discussion of the first investigation of CNT-sensor behavior and mechanistic investigations, we refer the interested reader to the reviews on CNT gas sensing mechanisms.36,37

Figure 2.

Schematic of sensing mechanisms in CNT-based sensors: (a) at the sidewall or the length of the CNT (intra-CNT), (b) at the CNT-CNT interface (inter-CNT), and (c) at the interface between the metallic electrode and the CNT (Schottky barrier).

1.1.1. Intra-CNT

Intra-CNT sensing mechanisms are modes of interaction between analyte and individual nanotubes or nanotube bundles. They include changes in the number or mobility of charge carriers and generation of defects on the walls of the tubes.

Charge transfer induced directly or indirectly by analyte interactions will modulate the conductance of the CNT by changing (decreasing or increasing) the concentration of the majority charge carriers. Under ambient conditions, CNTs are p-doped as a result of physisorption of oxygen molecules on their surface. Thus, exposure to further p-dopants will increase the hole conduction and cause a decrease in the resistance, while n-type dopants will induce the reverse effect.21,38–41 Direct charge transfer between the analyte and CNTs has been identified as a major sensing mechanism for polar analytes.21,41–43 In some cases this mechanism has a more localized nature. For example, interactions of a Lewis basic localized pair of electrons can create a local pinning force for cationic carriers as opposed to the fractional transfer of electron density to delocalized CNT states. For individual SWCNTs,21,39,44 charge transfer between analyte and tube can be observed experimentally through the current-voltage (I-V) characteristics, photoemission spectroscopy (PES), and Raman spectroscopy.

Investigation of I-V characteristics through field-effect transistor (FET) experiments is a powerful tool for probing the sensing mechanism of CNT-based devices. When plotting the current through the CNT material as a function of the applied gate voltage (transfer curve), different sensing mechanisms induce characteristic changes. Adsorption of electron donating species (charge transfer to the tube from the analyte) induces negative charge in the CNT, thus n-doping the CNT and shift the threshold voltage towards a more negative gate voltages and vice versa (Figure 3a).21 Modulation of the metal/CNT junction induces asymmetric conductance change, as electron- and hole-conductions are affected differently (Figure 3b). Lastly, a reduction of the charge carrier mobility through charge carrier trapping or scattering sites induces a reduction in conductance (Figure 3c).45,46 Any perturbation of the ideal SWCNT structure introduces charge scattering sites which reduce the mobility of the charge carriers and thus the conductance. Using I-V curves, changes in charge carrier mobility have been observed for scattering through adsorption of charged or polar species47–51 or via deformation of the tube.52

Figure 3.

Intra-CNT (semiconducting) sensing mechanism through changes in charge carrier concentration or mobility. Hypothetical transfer (I-Vg) curves and band diagrams before (black) and after (red) the exposure to the analyte for three different sensing mechanisms. The dotted line in the band diagram corresponds to the metal work function of the electrode and diagrams are given for both p- and n-type semiconductors interfaces with a metal. (a) n-Doping of the CNT induces a shift of the I-V curve to more negative voltages. The band diagram shows a hole doped CNT. (b) Schottky barrier modulation corresponds to a change of the barrier height between the work function of the metal electrode and CNT and asymmetric change in conductance for electron and hole transport. The band diagram shows change in barrier height for hole transport. (c) Change in mobility can be induced by the addition of resistive elements or carrier scattering which reduces the conductivity in both p- and n-type materials. Inspired by Ref. 53.

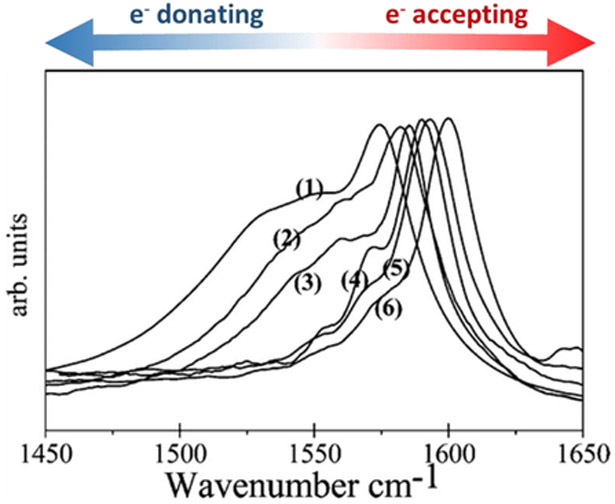

The effect of charge transfer on the doping levels of CNTs can also be estimated from shifts in the Raman spectrum.54–58 Wherein a shift of the G-band—stretching of the sp2 C-C bond in graphitic materials—towards higher wavenumbers is indicative of an electron-accepting analyte and a shift towards lower frequencies is indicative of electron-donating analyte (Figure 4). This shift can have a magnitude of ±30 cm−1 for strong dopants and has been observed for inorganic54 and organic dopants.59,60

Figure 4.

G-bands in the of Raman spectra of SWCNTs when interacting with electron donating and accepting molecules: (1) tetrathiafulvalene, (2) aniline, (3) pristine SWCNT, (4) nitrobenzene, (5) tetracyanoquinodimethane, and (6) tetracyanoethylene. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 59. Copyright 2008, American Chemical Society.

In addition to charge transfer effects, analytes can also promote the degradation of the CNT sidewalls. Particularly, the chemisorption of NO2 via formation of nitro- and nitrite-groups has been identified as a plausible sensing mechanisms.61–63 Soylemez et al.64 reported a chemiresisitive glucose sensor based on poly(4-vinylpyridine) (P4VP) wrapped SWCNTs functionalized with glucose oxidase. Upon exposure to glucose, hydrogen peroxide is formed which oxidizes the SWCNT sidewall. The degradation of the conjugated sp2 network of pristine CNTs increases the number of defect sites of the SWCNT, also observable as an increased D/G peak intensity ratio of the Raman spectrum. Strong localized interactions associated with carrier pinning can manifest increases in the D/G peak ratios.

1.1.2. Inter-CNT

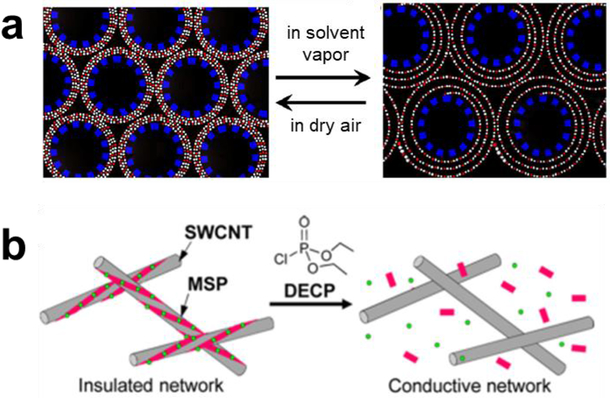

For devices consisting of a network of CNTs, mechanisms at the interface between tubes can have significant influence on the electronic properties of the overall network. Small changes in distance between two CNTs dramatically influence the contact resistance as the probability of charge tunneling decreases exponentially with distance.65,66 The inter-tube conduction pathways can be modulated either by partitioning of analytes into interstitial spaces between tubes or by swelling of the supporting matrix/wrapper. Alternatively, an analyte can trigger the disassembly of a molecular/polymer wrapping of the CNTs, Figure 5.

Figure 5.

CNT-based chemical sensor designed based on inter-CNT mechanism. (a) Illustration of polymer swelling upon exposure of a CNT/polymer composite to solvent vapors. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 70. Copyright 2007, Elsevier. (b) Schematic illustration of a chemiresistive sensor comprising SWCNTs and metallosupramolecular polymer (MSP) showing the polymer degradation upon exposure to chemical warfare agent mimic diethyl chlorophosphate (DECP). Reproduced with permission from Ref. 73. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

Swelling of a matrix material causes a decrease in the bulk conductance of CNT networks by increasing the width of tunneling gaps (Figure 5a). For example, Ponnamma et al.67 reported the influence of swelling on the electronic properties of a MWCNT-natural rubber composite. The swelling index was determined by quantifying the equilibrium uptake of a given solvent for all tested composites. They reported that the swelling index correlates with the magnitude of the decrease in conductance for all tested samples. Similar sensing behavior has been observed for porphyrins towards different VOCs,68 covalently69,70 and noncovalently71,72 attached polymers towards VOCs.

Alternatively, sensing systems that detect the increase in conductivity from new conducting pathways are similarly promising. Ishihara et al. reported the design of a sensor based on the de-wrapping of SWCNTs, which provided an increase of conductance by five orders of magnitude.73 In this case the SWCNTs were wrapped with a metallosupramolecular polymer designed to depolymerize upon contact with an electrophilic analyte (chemical warfare agent mimic, diethyl chlorophosphate), the depolymerization caused the formerly isolated SWCNTs to come into electronic contact (Figure 5b). Similarly, Lobez et al.74 and Zeininger et al.75 used CNTs wrapped by poly(olefin sulfone) (POS) polymers to detect ionizing radiation. Upon exposure to radiation, the meta-stable POS spontaneously depolymerizes with fragmentation resulting in an increase in the interconnections between CNTs and overall CNT network conductivity.

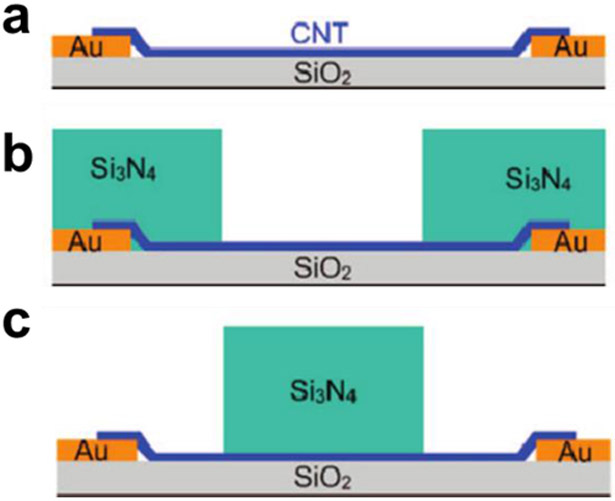

1.1.3. Schottky Barrier (SB) Modulation

In certain cases, the device performance is not only influenced by intra- and inter-CNT effects, but also by modulation of the junction of metal electrode and CNT (Schottky barrier). To differentiate between the previous mechanisms and effects at the electrode/CNT interface, several groups have observed the sensing behavior with and without passivation of the CNT/electrode contacts. In these experiments, passivating layers are deposited selectively over the whole device, over the areas where CNTs are in contact with the electrode, or over the length of CNTs that is not in contact with the electrodes (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Three sensor architectures to probe Schottky vs intra-tube sensing mechanisms. Schematic for (a) device with bare CNTs, (b) device with passivated CNT-electrode contacts, and (c) device with passivated length of CNTs that are not in contact with the metal electrode. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 76. Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society.

Bradley et al. contact-passivated different areas of a pristine CNT-device with SiO2 and tested the response of the resulting sensors towards NH3.77 They found that complete coverage with SiO2 drastically attenuated the response to NH3 exposure, proving SiO2 a suitable passivating material. Coverage of the electrode/CNT contact areas resulted in a sensor with comparable responsiveness and faster reversibility than the non-passivated sensor. From this result, they concluded that the NH3 sensing mechanism is the result of processes occurring over the length of the CNT, and not at the CNT/electrode interfaces. Liu et al. used poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) to passivate the channel of the electrode contact areas of a CNT-FET and detect NO2 and NH3.78 In contrast to Bradley et al., they observed changes in the transfer characteristics for both channel- and electrode-passivated devices suggesting that effect on both the metal/CNT junction and the length of the CNT have significant contributions to the sensor signal. Zhang et al. also employed PMMA to passivate the contact of a CNT device used to detect NO2, however they found that the sensing response is mainly due to the interface between electrode and CNT.79 Similarly, Peng et al. used devices partially passivated by Si3N4 and found that the sensing response towards NH3 mainly results from the metal-CNT junction.76 Considering the inconsistencies between these reports, it is understandable that the debate on the sensing mechanism persists.

To clarify the contradictory findings just discussed, Salehi-Khojin et al. investigated the sensing behaviors of CNTs with different defect levels.80 They reported that the dominating sensing mechanism is strongly dependent on the bottlenecks in the conduction pathways. For highly conductive CNTs, the sensing behavior is dominated by mechanisms influencing the electrode-tube junctions while the response of devices with less conductive, defect-rich CNTs is dominated by intra-tube effects. Generalization remains difficult as a result of the fact that there can be different types of defects in CNTs and other components in the sensor material can influence intra-tube and metal-tube electron transport.

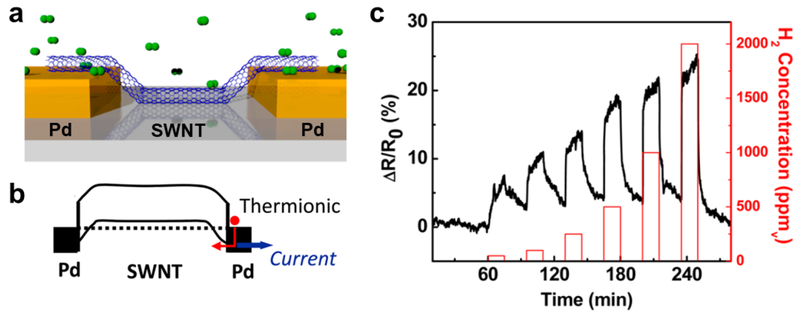

Apart from the nature of the CNTs, the choice of metal for the electrode also influences the behavior of the CNT/electrode junction. Kim et al. reported increased sensing responses from CNT devices containing Pd instead of Au electrodes. 81 This result was attributed to the stronger interactions between the Pd surface and CNTs and the resulting barrier-free electronic transport across the junction, which agreed well with several theoretical studies.82,83 Zhang et al. demonstrated that targeted disruption of this Pd/CNT junction is a useful approach to fabricate H2 sensors using CNTs without any further functionalization. 84 A further discussion on the H2 sensing capability of Pd/CNT junctions can be found in section 2.1.2, Hydrogen (H2) and Methane (CH4).

1.2. Functionalization of CNTs

As mentioned previously, pristine CNTs have very limited selectivity when interacting with analytes. In this context, CNT functionalization is needed to tailor sensitivity and selectivity toward target analytes. Functionalization is also critical to improving the solution processability, enabling processing of these otherwise insoluble nanomaterials. Various approaches exist for the functionalization of CNTs, and they can be grouped as noncovalent and covalent modifications. Anchored chemical groups, macromolecules, or biomolecules that serve a function to recognize, interact, or react with a target analyte selectively are referred to as selectors. Noncovalent functionalization involves the adsorption of small molecules (often surfactants) to the surface of CNTs or wrapping of polymers and biomolecules around the tubes. Covalent functionalizations utilize reactions to attach chemical groups covalently to the conjugated surfaces or termini of CNTs. Covalent functionalization has the advantage that it can produce strong and stable anchors of functional groups to CNT, however the rehybridization of the carbon atoms from sp2 carbons to more sp3 character on the surface of CNT at the attachment sites lowers the electronic delocalization thereby perturbing their intrinsic optical and electronic properties. Therefore, careful control of the degree of functionalization is important to achieve an optimal balance between covalent anchoring of selectors and perturbation of the π–surface. Noncovalent approaches are generally less perturbative to the intrinsic properties of CNTs. However, physisorbed selector molecules or coatings have limited stability and can display changes in their configuration around the CNT, undergo phase segregation, and can even desorb in solution-based applications. Covalently functionalized carbon nanotubes are in general more robust for applications in environmentally challenging conditions. Several approaches to the functionalization of CNTs to impart sensor selectivity are described here. Comprehensive reviews of other functionalization methods that have not been applied in sensors are available elsewhere.11,85

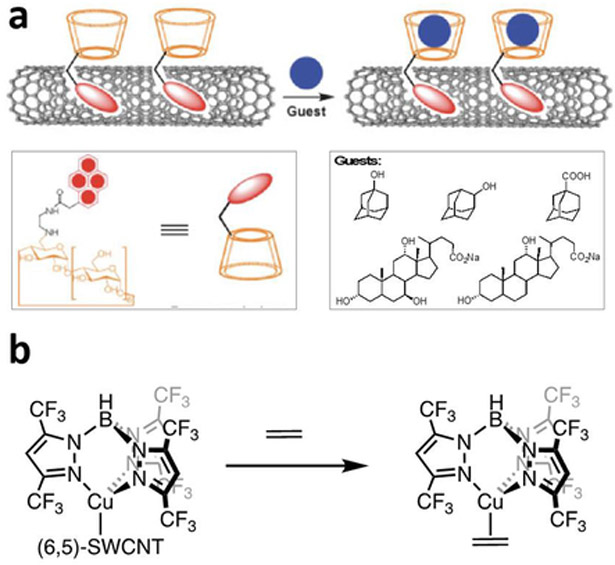

1.2.1. Noncovalent Functionalization of CNTs with Small Molecule Units

CNTs can be functionalized noncovalently by physisorption of small aromatic molecules and surfactants through π-π and hydrophobic interactions. Dai and co-workers reported a simple and general method of immobilizing proteins onto CNTs using a bifunctional molecule containing a pyrene moiety for CNT adsorption and a succinimidyl ester for attachment of proteins by nucleophilic substitution reaction with the proteins’ surface amine functional groups. The immobilized proteins can be observed with atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This method is highly specific and efficient for immobilization of biomolecules, and the authors demonstrated the attachment of biotinyl-3,6-dioxaoctanediamine and two proteins, ferritin and streptavidin.23 Other functionalities anchored by pyrene units include amino-groups,86 cyclodextrin (Figure 7a),87 and boronic acid88 were used for the detection of trinitrotoluene (TNT), organic guest molecules and glucose respectively. Bis(trifluoromethyl) aryl groups are also suitable for noncovalent functionalization.89

Figure 7:

Noncovalent functionalization of CNTs with small molecules. (a) SWCNTs noncovalently functionalized with pyrenylcyclodextrins, which in a chemitransistor can detect closely related analogues of adamantane and sodium cholate. Reproduced with permission from Ref.87. Copyright 2008, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. (b) Chemiresistive sensor using a composite of SWCNTs functionalized by coordination of a fluorinated tris(pyrazolyl)borate copper (I) complex to the π-sidewalls to provide selectivity to ethylene gas.

Simple physical mixtures of CNTs and a small molecule or macromolecule selectors can impart selectivity in gas sensing. Composites made of CNTs dispersed with small aromatic units can however produce inhomogeneous compositions with variable performance. Successful gas detection has been realized with physical mixtures of CNTs with selectors that can interact with desired analytes through various supramolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding,90 halogen bonding,91 π-π,92 metal-ligand (Figure 7b),93–96 and host-guest interactions.97

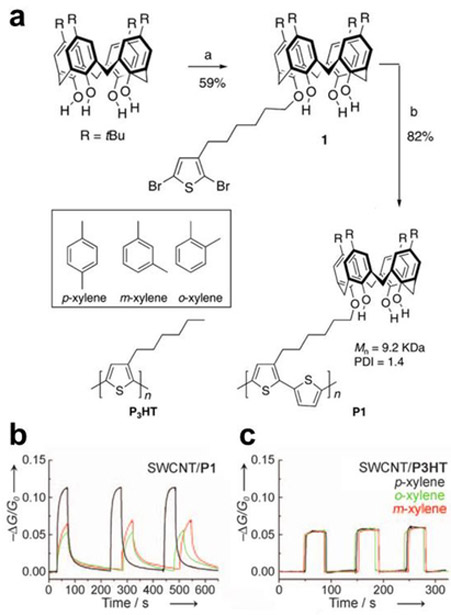

1.2.2. Wrapping of CNTs with Polymers

Polymer wrapping represents a noncovalent approach of solubilizing and functionalizing CNTs, wherein the collective contacts can provide for a stable composition. CNTs can be efficiently dispersed in water with sonication in the presence of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) as a result of multiple favorable π-π interactions.98 Hydrophobic interactions with polymers having surfactant characteristics can drive solubility in water and saccharides and polysaccharides are capable of solubilizing and functionalizing CNTs. Although CNTs are not soluble in an aqueous starch solution, they are soluble in starch-iodine complex. Stoddart and co-workers attributed these observations as a result of preorganization of amylose in starch into a helical conformation by iodine. Displacement of iodine inside the helix by CNTs by a “pea-shooting” mechanism leads to amylose wrapped CNTs. The water-soluble starch-wrapped CNTs dispersions can undergo triggered disassembly by enzymatic hydrolysis with amyloglucosidase.99 Addition of this enzyme to starch-wrapped CNTs results in quantitative precipitation within 10 minutes.100 A variety of saccharides and polysaccharides101,102 have been used for the noncovalent functionalization of CNTs.103 Conjugated polymers are a natural class of CNT-wrappers and drawn much attention. Conjugated polymer-wrapped CNTs can be obtained by polymerizing an appropriate monomer in the presence of CNTs104 or by two component mixing.105 Swager and co-workers showed that conjugated polymers attached to selector side chains can provide selectively for the detection specific analytes and even resolve very similar structural isomers. 47,73,97,106,107 CNTs can also be functionalized with polymeric surfactants containing long alkyl chains that interact via hydrophobic interactions.108,109 Dai and co-workers demonstrated the adsorption of Tween 20 conjugates containing biotin, staphylococcal protein A (SpA), or human autoantigen U1A to CNTs. Polyethylene oxide chains of Tween 20 block the surface of CNTs and are crucial to suppress nonspecific binding of proteins.108

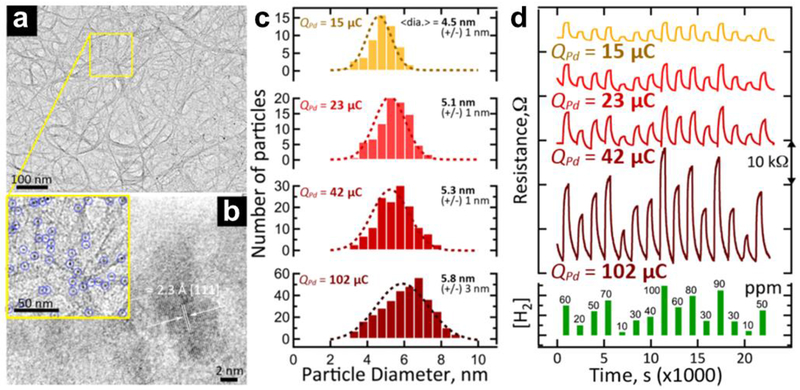

1.2.3. CNTs Decorated with Metal Nanoparticles

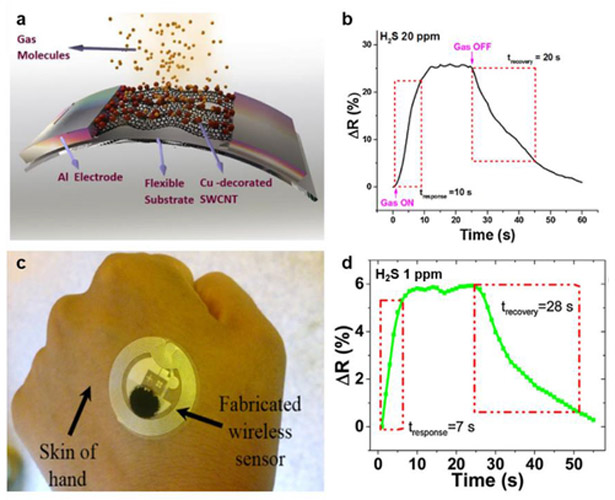

Although many examples of sensors based on unfunctionalized “pristine” CNTs have been reported, it is important to note that residual metal catalysts or particles left from the CNT production process have been accredited for the sensitivity of unpurified CNTs to certain analytes.2 As a result, intentional incorporation of metal nanoparticles represents a productive approach for producing specific or stronger responses. Unfunctionalized CNTs are insensitive to H2 gas, but electron beam evaporation of 5 Å of palladium (Pd) onto CVD-grown single CNT or CNT networks provides sensitivity to H2 gas at 4 – 400 ppm level in air at room temperature. The high sensitivity is understood to stem from the dissociation of H2 to atomic hydrogen on Pd. This process lowers the work function of Pd and subsequently causes electron transfer from Pd to CNT, decreasing the carrier density and conductivity of p-type CNTs.110 Using a “dry transfer printing” process, Sun et al. showed that CNT chemiresistive devices functionalized with Pd nanoparticles could be fabricated on flexible poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) substrate that can withstand 1000 cycles of bending and relaxing without significant sensing performance degradation.111 Deshusses and co-workers electrochemically deposited gold nanoparticles from commercially available ready-to-use gold electroplating solutions onto spray printed carboxylated-SWCNT films on gold electrodes. The resulting chemiresistive sensors can detect H2S in air at room temperature with a limit of detection of 3 ppb.112 Similar to H2, unfunctionalized CNTs are also insensitive to carbon monoxide. The functionalization of CNTs with SnO2 nanocrystals can overcome the inherent insensitivity of MWCNTs to H2 and CO gases as well as enhancing sensitivity to NO2. Chen and co-workers showed that MWCNTs decorated with SnO2 nanocrystals can detect ppm levels of NO2, H2, and CO gases at room temperature, an improvement over existing SnO2 sensors which operate typically at temperatures over 200 °C. Uniform decoration of ~2 to 3 nm sized SnO2 nanocrystals was achieved by deposition of aerosol SnO2 onto MWCNTs on gold interdigitated electrodes by electrostatic-force-directed assembly (ESFDA).113

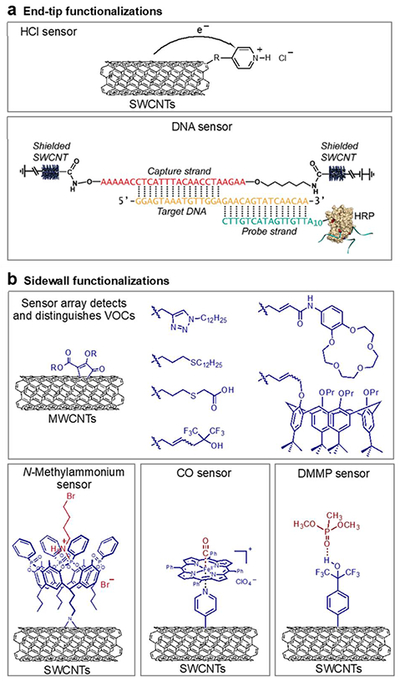

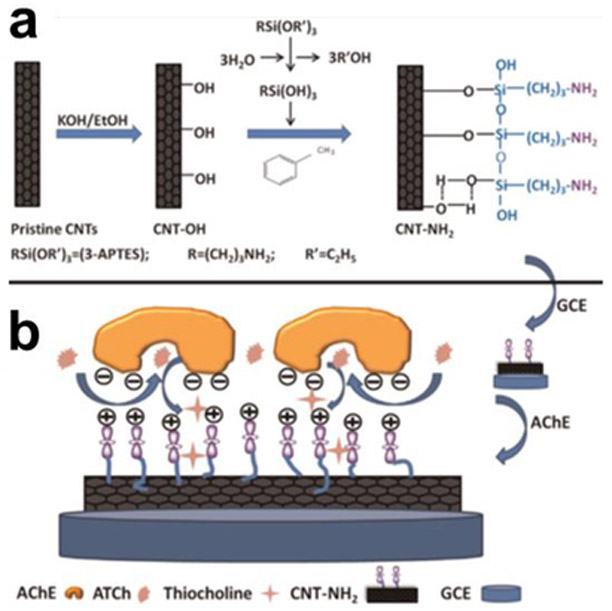

1.2.4. Covalent Functionalization

Although noncovalent functionalization appears attractive towards tailoring the selectivity of CNT sensors, long-term stability, robustness, and leaching of noncovalent coatings remain a concern.114,115 Covalent functionalization offers strong and stable anchoring of functional groups which allows the robust applications of functionalized CNTs in harsh environmentally challenging conditions and for in vivo studies.116,117 Using covalent modification, selectors can be precisely attached to CNTs via their termini or sidewalls for long-term stability and reproducibility with well-defined chemical composition.

The capability of the CNT graphene sidewalls to undergo chemical reactions has led to the development of an extensive collection of covalent functionalization methods.11,85 Zhang et al. developed a highly efficient modular functionalization method capable of attaching a variety of chemical groups to the sidewall of CNTs. The reaction involves the addition of zwitterionic intermediates formed in situ from 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) and disubstituted acetylenedicarboxylates to the surface of CNT.118,119 Versatile, functional handles including terminal alkynes and allyl groups can be grafted, which can allow post-functionalization procedures such as 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, thiol-ene addition, and olefin cross-metathesis reactions for further diversification. Using this method, sidewall-functionalized MWCNTs consisting of allyl, propargyl, alkyl triazole, thioalkyl chain, carboxylic, HFIP, calix[4]arene, and crown ether groups were synthesized and fabricated into chemiresistive sensors that were able to selectively identify a diverse array of volatile organic compounds, Figure 8.

Figure 8:

Examples of covalent functionalization of CNTs: (a) End-tip and (b) Sidewall functionalization. The DNA sensor scheme is adapted with permission from Ref. 120. Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

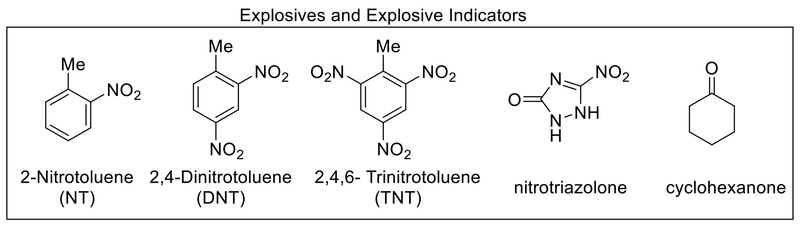

Thermal aziridination using organic azides provides access to covalently functionalized CNTs that has been theoretically suggested to provide minimal perturbation to the transport properties.121–123 Early recognition of this advantage by Schnorr et al. resulted in focused study on a variety of SWCNTs containing hydrogen bonding groups such as thiourea, urea, and squaramide via thermal aziridination of 3-azidopropan-1-amine followed by another step to attach the selectors. The resulting SWCNT chemiresistive sensor array consisting of different hydrogen bonding groups was able to detect ppm levels of cyclohexanone and nitromethane, vapor signatures of explosives. These sensors are highly reproducible between measurements and exhibit long-term stability, critical parameters to consider regarding practical applications.122 Thermal aziridination was also employed in the covalent functionalization of SWCNTs with a tetraphosphonate cavitand for N-methylammonium detection in aqueous conditions. Sarcosine, a potential biomarker for prostate cancer, and its ethyl ester hydrochloride derivative can be selectively detected in water at concentrations of 0.02 mM (Figure 8b).124 More recently, SWCNTs covalently functionalized with methyl pentafluorobenzoate and pentafluorobenzoic acid via aziridination enabled the detection of low ppm levels of ammonia and trimethylamines at room temperature. The sensors show no interference from volatile organic compounds and are operational in air and under high humidity.125

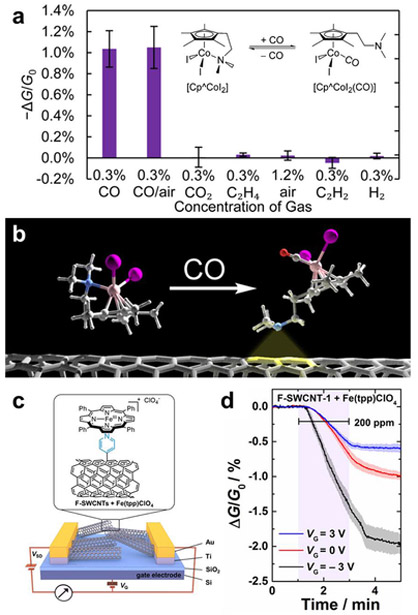

He and Swager used a reductive approach and functionalized CNTs with different aryl groups and N-heterocycles. CNTs were first reduced with sodium naphthalide in THF in situ followed by addition of aryl iodonium salts.126 CNT attachment of pyridyl groups at the 4-position is particularly useful for the anchoring of transition metal complexes. The potential of this pyridyl anchor was exemplified by the localization and electronic coupling of iron porphyrins (Fe(tpp)ClO4) to CNTs functionalized with pyridyl groups in the development of heme-inspired carbon monoxide sensors (Figure 8b).127 Although covalent functionalization is critical to achieving higher sensor sensitivity, excessive functionalization can disrupt the π-surface of CNTs increasing the base resistivity and lower sensitivity. Therefore, optimal sensor response to a targeted analyte requires a well-controlled degree of covalent functionalization.

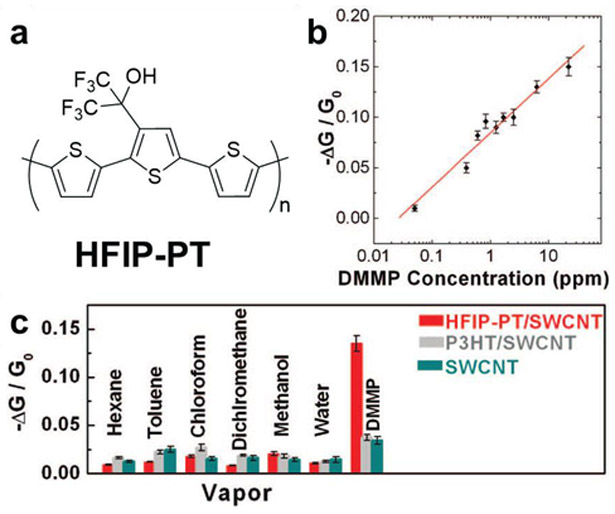

Covalent functionalization by reactions with diazonium ions is widely used on carbon nanomaterials. Liu and co-workers functionalized SWCNTs with pendant hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) groups with a degree of functionalization of 1 HFIP per 75 carbons for DMMP detection. The HIFP attachment was conducted by in situ generation of an aryl diazonium ion through reaction of 2-(4-aminophenyl)-1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-ol with isoamyl nitrite at 70 °C. Johnson and co-workers covalently attached antibodies to SWCNTs functionalized with aryl groups containing sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinamide (NHS) esters.128,129 Considering the invasive characteristics of covalent functionalization, Wang and co-workers heavily functionalize the outer wall of double-walled CNTs (DWCNTs) with 4-benzoic acid moieties using diazonium chemistry. Since the inner tube is sealed and protected by the functional outer tube, the interaction between functional groups on the outer wall can induce an electrical change to the inner wall.116

Various metal oxides can be covalently attached to CNTs using sol-gel processes .130,131 The synthesis of CNT-metal oxide using a sol-gel process involves the oxidation of CNTs to generate carboxyl and hydroxyl groups on the graphitic surface. These groups can react with a colloidal solution (sol) of metal alkoxide or metal halide precursors. Subsequent hydrolysis and condensation reactions provide an integrated network (gel) of metal oxide on CNTs. Resulting CNT-metal oxides commonly give one-dimensional core-shell structures. Liang et al. provided an early example of MWCNTs coated with tin oxide nanocrystal via sol-gel method from tin(II) chloride that can detect ppm levels of NO, NO2, ethanol, and acetylene gas at 300 ºC.132 Additionally, the thickness of the tin oxide shell can influence the sensing properties.133 Other examples include MWCNTs functionalized with silica network and gold nanoparticles for the electrochemical detection of dopamine and ascorbic acid,134,135 and SWCNT-TiO2 core-shell hybrids synthesized using titanium isopropoxide as a precursor that possess a unique photoinduced acetone sensitivity.136 Moreover, SWCNT-indium oxide hybrids can be prepared from oxidized SWCNTs and indium chloride in ammonium hydroxide. The crystallinity of indium oxide, as controlled by the temperature of calcination, was reported to be important to the sensor’s response to acetone and ethanol.137 Similar to the synthesis of other metal oxides, SWCNT-CuO hybrids were prepared from copper(II) chloride in ammonium hydroxide and found sensitive to ethanol vapors and humidity at room temperature.138

Attachment of chemical groups or macromolecules to the ends of CNTs is generally achieved via amidation or esterification reactions with the carboxylic groups on oxidized CNTs that have been shortened by controlled acidic oxidation.139–141 Although these strong acid oxidative treatments can damage and shorten CNTs, subsequent end-tip functionalization doesn’t perturb the π–surface of CNTs. Haddon detected hydrogen chloride by introducing basic sites at the SWCNT ends through covalent attachment of pyridines (Figure 8a). The protonation of pyridine groups by hydrogen chloride induces the electron transfer from semiconducting SWCNTs. The sensor responded with decreasing resistivity because of holes are introduced to the valence band of semiconducting SWCNTs.142

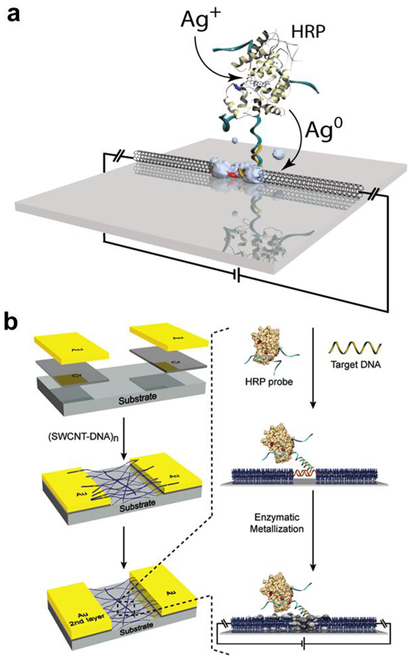

Biomolecules can be precisely positioned at the ends of single CNT and CNT networks for sensing applications. Nuckolls and co-workers elegantly cut individual SWCNT positioned between two gold electrodes using electron-beam lithography and oxygen plasma ion etching to open a nanometer-scale gap.143 The gap was covalently bridged via amide coupling with amine-functionalized single-stranded DNA. Well-matched duplex DNA was shown to mediate charge transfer between the two SWCNT ends. The single CNT-DNA device was able to detect a single base pair mismatch in a 15-mer DNA with an increase in resistance relative to a well-matched oligomer.144 Schemes for the regiospecific covalent functionalization of CNT ends with biomolecules suffer several limitations, including nonspecific surface adsorption, the introduction of defect sites on the sidewall during oxidation process, and aggregation of tubes. Weizmann et al. exquisitely utilized a surface protection strategy to achieve regiospecific terminally linked DNA-CNT nanowires that addresses the limitations in bulk. In this strategy, strong-acid-oxidized SWCNTs were surface protected through surfactant and polymer wrapping with Triton X-100/PEG (Mn = 10,000), followed by amide coupling with amine functionalized DNA at the termini to form DNA-CNT nanowires.145 The specificity of this process was also confirmed by the selective attachment of gold nanoparticles to the CNT termini.146

1.3. Device Architecture and Fabrication

CNTs can be integrated in a straightforward manner into a variety of electronic device architectures with a variety of fabrication approaches. The design choices for devices utilizing CNTs as an electrical component of a sensor will be discussed in this section. Fluorescent sensors or other sensors that take advantage of the optical properties of CNTs have been reviewed elsewhere.26,27 This review will also not discuss the use of CNTs as tip augmentations of scanning probe microscopies.147,148

1.3.1. Single CNTs vs CNT Networks

While the chemistry of pristine and functionalized CNTs is the primary parameter to tune sensor selectivity and sensitivity, the choice of CNT quantity and morphology also plays a large role in determining sensor characteristics.5,149 Devices using individual CNTs (Figure 9a), wherein a single chemical event can interrupt all of the transport,20 can have higher sensitivity and a lower limit-of-detection than devices using multiple CNTs. Single-molecule sensors have been claimed using single-CNT architectures.144,150–157 From a purely scientific standpoint, single-CNT devices offer the ability to eliminate complexity from inter-CNT interactions, thereby simplifying the chemical sensing mechanisms (see Section 2.1) and precluding sensor drift/degradation that results from long-term movement/settling of CNT networks (see Section 2.4). However single-CNT devices are more time-consuming to fabricate and characterize than CNT network devices, and their lower signaling electrical currents also require more expensive measurement equipment. Furthermore, CNT-to-CNT variation and device-to-device reproducibility remains a challenge.

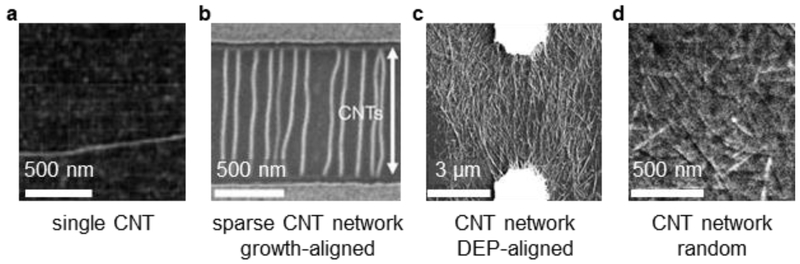

Figure 9.

AFM/SEM images of (a) single CNT21 (b) sparse, growth-aligned CNT network162 (c) dielectrophoresis (DEP)-aligned CNT network168 and (d) random CNT network.169 Images adapted with permission from Ref. 162 Copyright 2017, Nature Publishing Group; Ref. 21, Copyright 2000, American Association for the Advancement of Science; Ref. 168, Copyright 2010, Springer; Ref. 169, Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

Sensors using CNT networks (Figure 9d) can be quickly and inexpensively fabricated with a variety of methods (vide infra). The response of a CNT network offers higher device-to-device reproducibility than single-CNT devices, but metallic CNTs in the network are less sensitive to analytes than semi-conducting CNTs, and overall sensor response can be attenuated.51 For optimal intra-CNT sensing responses, the CNTs should be debundled, so that charge carriers remain accessible to analyte interactions and/or coupled to selector/receptor groups.51,158 For sensors in which inter-CNT effects are proposed to determine electrical response, analogous single-CNT devices would exhibit no response. The nanotube density is also an important consideration, as lower-density films with higher surface-to-volume ratios have been shown to offer higher sensitivity and lower detection limit.159

As an intermediate between single CNTs and random CNT networks, aligned CNTs can be used (Figure 9b,c). When compared to single-CNT devices, the baseline noise of aligned CNT sensors can be much lower,160 and device yield/reproducibility is higher. Relative to random CNT networks, aligned CNTs, if sparse enough, can limit inter-CNT effects and exhibit higher sensitivity.51 Highly aligned, sparse CNT networks have been made with a variety of techniques including growth along a surface template,161,162 spin-coating,51 deposition in lithographically patterned trenches,163 and alignment along solution interfaces.164,165 Aligned CNT networks in which neighboring CNTs are intertwined and in electrical contact with each other (Figure 1c) exhibit anisotropic electrical properties that can be measured either along or perpendicular to their alignment axis.166 For a detailed review on the comparison of random CNT networks and aligned CNTs in different electronic devices we refer the reader to review articles out of John Rogers’ group.4,167

1.3.2. Device Architectures

1.3.2.1. Transistors

The field-effect transistor architecture utilizing CNT(s) as the active channel (CNT-FET) is a versatile sensor platform (Figure 10a). Early CNT-based chemical sensors, reported by Kong and Dai, were chemically responsive transistors (chemitransistors), obtained by chemical vapor deposition growth of an individual SWCNT across patterned Pd catalyst islands on SiO2/Si layered substrate.21,170 In chemitransistors, the channel current (ISD) across a range of gate voltages (VG) is compared before and after analyte exposure. Thus, one ISD-VG curve offers many features, and seemingly subtle changes can be accurately correlated with analyte exposure using linear discriminate analysis.171 To optimize sensitivity, the CNT active channel should be semiconducting and not metallic, which is an issue considering currently as-produced SWCNTs are mixtures of chiralities. In addition to the back-gate architecture, chemitransistors can utilize a top-gate architecture, in which a dielectric and metal gate electrode are deposited on top of the CNT(s). The top dielectric layer partially passivates the CNT against degradation, but also limits direct CNT–analyte interactions, which can lower sensor response.161,172

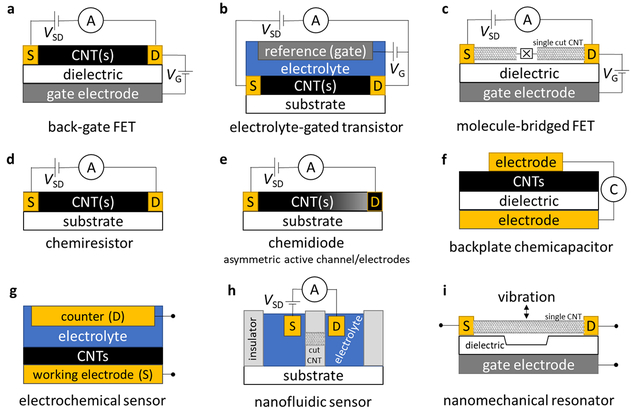

Figure 10.

Illustrative CNT sensor architectures: (a) back-gate FET, (b) electrolyte-gated transistor, (c) molecule-bridged FET, (d) chemiresistor, (e) chemidiode, (f) back-plate chemicapacitor, (g) electrochemical sensor, (h) nanofluidic sensor, and (i) nanomechanical resonator. S = source, D = drain, Ⓐ = ammeter, V = voltage, Ⓒ = capacitance meter, ⌧ = molecular bridge.

The dielectric and gate electrode layers of a conventional solid-state FET can be replaced with liquid electrolyte and an electrochemical gate electrode. This electrolyte-gated transistor (EGT) architecture (Figure 10b), originally developed for the study of conjugated organic polymers and referred to as electrochemical transistors,173 is also referred to in the CNT literature as an electric double-layer transistor.174–176 The CNT-EGT architecture targets solution-phase analytes and can be incorporated into microfluidic sensors.177 CNT-EGTs exhibit higher on-off ratios with lower switching potentials than CNT-FETs operated via a conventional back-gate.178,179 These advantages translate to CNT-EGT sensors, as small changes (< 500 mV) in VG can result in markedly improved analyte sensitivity.179

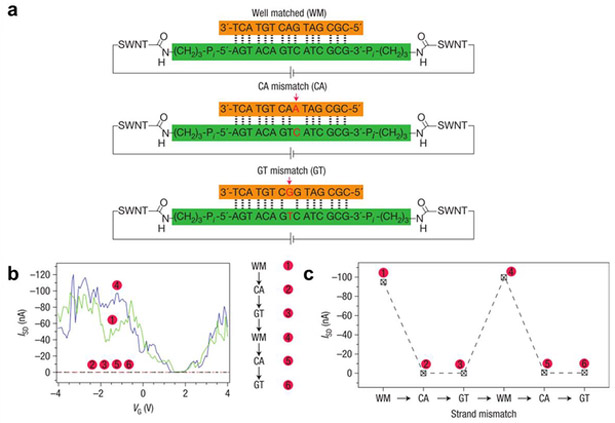

In addition to serving as the active channel, CNTs can serve as the electrodes for molecule-bridged transistors (Figure 10c). Single CNTs are precisely cut by electrical breakdown or lithographically patterned etching, and the resulting nm-scale gap can be bridged by a variety of conductive (redox-active) molecules.143,157,180 The chemical responsiveness of the bridging unit has been leveraged to detect pH, metal ions, proteins, and DNA.143,144,157 When the CNT gap is bridged by single-stranded DNA, conductivity increases upon formation of a DNA duplex with the complementary strand. However, if the complementary strand contains one base-pair mismatch, conductivity decreases nearly 300-fold.144 Fabrication of these CNT-molecule-CNT junction chemitransistors is not trivial, but the sensing response of proposed molecular linkers can be evaluated in silico prior to fabrication.181

1.3.2.2. Two-Electrode Solid-State Sensors

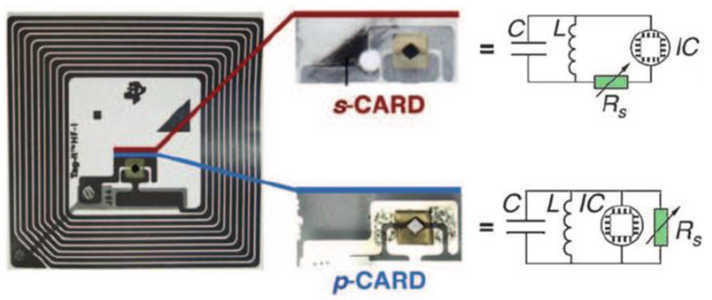

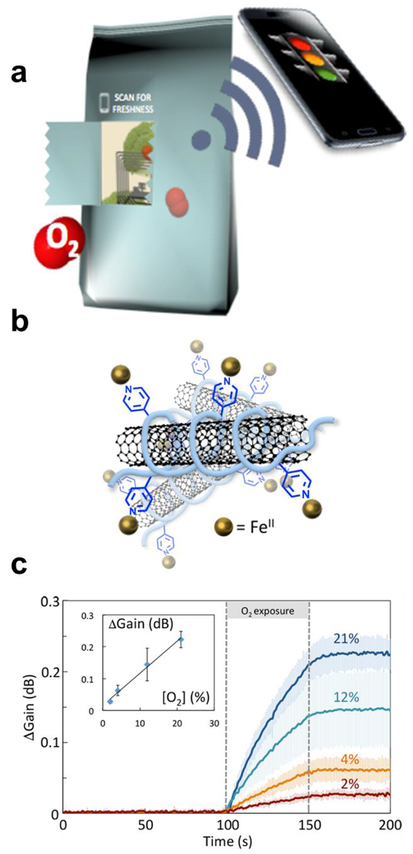

While the three-electrode transistor architecture offers much more data for sensing analysis, architectures using only two electrodes offer operational simplicity that would be suited for distributed, low-cost sensors. In the absence of applied gate voltage, CNTs can exhibit changes in conductivity on exposure to analytes. These chemically responsive resistors (chemiresistors, Figure 10d) constitute a very simple sensor design with minimal power and instrumentation requirements. In liquid-phase electrochemical systems, these sensors have been referred to as chemiresistive,182,183 conductometric,184 or amperometric.185 In this review, we reserve the term amperometric sensing for electrochemical sensors in which electrolyte solution plays an integral role in the conduction pathway. Chemiresistors benefit from low cost and ease of fabrication, which allows for rapid screening of a diverse array of selectors.68,93,117,186,187 Their low operational power requirements can enable wireless sensor networks, where the CNT chemiresistor is incorporated into passively powered RFID tags (Figure 11).90,107,188,189

Figure 11.

Two methods to integrate CNT chemiresistors into commercial RFID tags (left) and their equivalent circuit diagrams (right). Reproduced with permission from Ref. 90. Copyright 2016. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH &Co. KGaA.

Most chemiresistors are characterized using a single small bias voltage (VSD). At higher bias voltages, the ISD–VSD curve for CNTs deviates from Ohm’s law linearity for an ideal resistor.190 Analysis of the non-linear voltage regime could allow extraction of more data from chemiresistive sensors. This approach has been used for Pd-CNT-Pd devices to sense H2 via Schottky barrier modification.84

A non-linear, rectifying ISD–VSD curve is expected if the chemiresistor architecture is sufficiently electronically desymmetrized. Such a chemidiode (Figure 10e) changes its ISD–VSD curve upon exposure to analyte. If the source and drain electrodes are materials with different work functions, then a Schottky diode is formed. A Pd-CNT-Si Schottky diode has been used to sense H2.191 Symmetric metal-CNT-metal devices can detect asymmetric deposition of a second metal at one of the electrodes via the resulting rectified ISD–VSD curve.192,193 Alternatively, the p-type CNT active channel can be asymmetrically functionalized with molecular,169 polymeric,194 or metallic n-dopants to form p–n rectifying diodes.195 Current reports of chemidiodes have focused primarily on the observation of increased rectifying behavior upon exposure to a single high concentration of analyte. Calibration of chemidiodes against a range of analyte concentrations is a promising approach for future research to consider.

CNTs can also be used as the active element in a conductor/dielectric/conductor capacitor architecture. Although the capacitance between an individual CNT and a gate electrode has been studied,196 capacitive sensing studies have primarily utilized CNT networks/films (chemicapacitors, Figure 10f), often in a FET-type architecture with separate source and drain top electrodes. Using a parallel-plate capacitor model or a RC transmission line model, gate capacitive measurements of CNT films on back-gate FET devices have been used to estimate CNT coverage density.197,198 The capacitance of the film changes upon exposure to analyte, as a result of the polarization of analyte molecules near the CNT surfaces. Snow and coworkers reported that CNT-based sensors exhibit larger responses with faster recovery kinetics in capacitance rather than in resistance mode.199,200 However, a study by Esen and coworkers using an RC transmission line model attributed the bulk of the chemicapacitive response of a CNT film to changes in its resistance.201 An alternative measure of chemicapacitance is to connect a two-terminal chemiresistor-like device to an AC voltage source and impedance analyzer, and to model the source–drain capacitance and resistance of the equivalent circuit. Using this method, ammonia vapors exhibit a faster and larger capacitance than conductivity response,202 and CO2 was found to exhibit a capacitive response but not a resistive response. 203

1.3.2.3. Electrochemical Sensors

CNT films can function as electrodes for solution-phase electrochemical sensors (Figure 10g).8,204 When used with biological selectors/analytes, these are also referred to as biosensors. Their high specific surface area allows wide dynamic sensor range, resistance to fouling, and high loadings of electrocatalysts or selectors. CNT films have been functionalized with a variety of enzymes to amperometrically detect biological analytes. Potentiometry has been used for CNT-based pH sensors.185,205–207 Potential differences generated in solution can be amplified by using the CNT electrode as an extended gate electrode for a metal-oxide-semiconductor FET (MOSFET) chip.208 Voltammetry measurements, requiring a potentiostat, assist in analyzing complex mixtures by separating electroactive species by their redox potentials.209,210 This is particularly useful for distinguishing and quantifying different dissolved metal ions.211,212

A single CNT with open ends from oxidative cutting can function as a well-defined, size-selective pore to separate the cathode and anode, forming a nanofluidic sensor (Figure 10h). Amperometric measurements show a change in electroosmotic current as analytes pass through CNT pores. Based on the magnitude and duration of the current change, similar analytes can be distinguished from one another; this has been applied to discrimination of different alkali metal ions,155 oligonucleotides of varying length,156 or differently charged dye molecules.213 In a more advanced architecture, a top-gate electrode can be fabricated for the CNT pores, resulting in a nanofluidic FET which provides more data for distinguishing various analytes.214

1.3.2.4. Miscellaneous

Electronic analytical methods based on resonant frequencies have been augmented by incorporation of CNT(s), such as circular disk resonators215,216 and quartz crystal microbalance217 (QCM). The details of these analytical methods are beyond the scope of this reference. However, it should be noted that a suspended individual CNT in a modified FET-type device can be driven into resonant vibration modes by applying offset sinusoidal potentials from the gate electrode (Figure 10i). Such nanomechanical resonators have been used to detect minute mass changes on the CNT.218 A side-gate device has been used to detect adsorption of naphthalene molecules or xenon atoms to the CNT with impressive yuctogram-scale resolution (1 yg = 10 −24 g).154 Thus far, these studies have only been conducted on unfunctionalized CNTs.

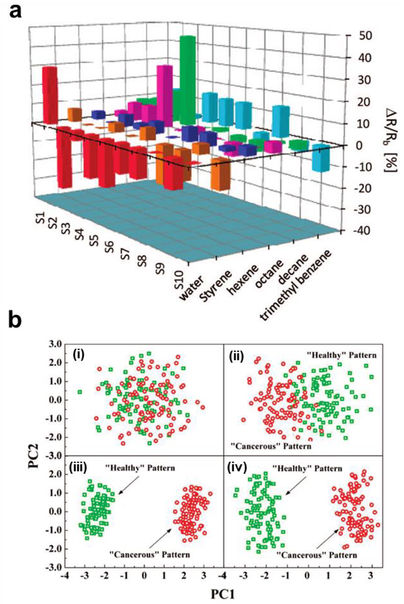

1.3.2.5. Sensor Arrays

To better identify or quantify analytes from complex sample mixtures, multiple sensing elements can be integrated onto the same device, often using shared counter/drain/gate electrodes. Ishihara and coworkers elegantly used a minimal array consisting of two chemiresistors to make a formaldehyde sensor.219 One element, functionalized with hydroxylamine hydrochloride, becomes more conductive upon exposure to formaldehyde vapors, while the other element is unresponsive to formaldehyde but serves as a reference to account for conductivity changes arising from humidity and temperature variations. More elaborate multichannel arrays can be formed from a variety of cross-reactive sensing elements, in which a variety of analytes can be determined simultaneously, in a process reminiscent of olfaction/taste.22 Electronic noses/tongues comprised of CNT electrical elements have been used to discriminate between a variety of analytes such as volatile organic compounds68,117,122 or malignant vs. healthy cells.171 By giving a sensor array a training set of samples, fingerprint responses can be determined with mathematical techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA).220

1.3.3. Fabrication

To incorporate CNTs into electric devices, there are two general fabrication strategies: fabrication using as-grown CNT films or the deposition of purified CNTs. The former approach, usually performed via high-temperature chemical vapor deposition onto pre-patterned electrodes, produces robust electrode/CNT contacts, and with sparse CNT deposition, bundling and inter-CNT effects can be avoided. However, for as-grown single-CNT devices, it is difficult to control the angle of CNT growth between electrodes, and device yield is low, especially for larger channel lengths.21,170 Additionally, for as-grown CNT devices, a distribution of CNT diameters and chiralities are formed, and limited on-device purification steps are available. Metallic CNTs can be preferentially disrupted using electrical breakdown162,221,222 plasma etching,223 thermal oxidation,224 or irradiation,225 resulting in higher on-off ratios for CNT transistors. CNTs aligned during growth can be alternatively transferred to different substrates with lift-off techniques.6,226

In contrast, device fabrication strategies that rely on deposition of pre-formed CNTs can take advantage of solution-based functionalization schemes (Section 2.2) and purification strategies, which can enrich specific diameters or chiralities.227,228 The purified CNTs can be further purified/treated after deposition to enhance transistor on/off ratio, chemitransistor sensitivity, and response time.229 CNTs can be deposited onto pre-patterned electrodes, or vice-versa, electrodes can be deposited onto CNTs. The former method is convenient for laboratory research, as pre-patterned electrodes can be produced in bulk. However, in these cases the CNTs are only held onto the electrode weakly, and device performance may drift as a result of a high and variable contact resistance at the CNT-electrode interface.230 In contrast, post deposition of metal electrodes onto CNTs fixes them in place with greater contact areas and lower contact resistances.231

Deposition of CNTs from a suspension by inkjet printing, spray-coating, spin-coating, dropcasting, or doctor blading can fix CNTs in place by rapid removal of solvent. Alternatively, CNTs can be deposited using external forces to make more robust CNT materials. Such techniques include layer-by-layer assembly210 and alternating current dielectrophoresis (DEP).202 Variation of AC waveform, electrode geometry, and substrate all play a role in DEP, and individual CNTs can be repeatably deposited. The resulting aligned CNT devices exhibit higher on/off ratios than random network devices.4

Solvent-free deposition methods for purified CNTs have also been explored. Mirica and coworkers pioneered abrasive deposition using compressed pellets of CNTs ball-milled with selectors.91,187,232 Abrasive deposition is a simple, low-cost, and rapid fabrication method suitable for teaching laboratories and rapid prototyping.233 Limitations of this method include the need for a rough substrate, the use of relatively large amounts of CNTs (~25–150 mg) to fabricate one compressed pellet, and the limited mechanical integrity of pellets, which is particularly acute with poorly adhering selectors (e.g. TiO2 nanoparticles). Adhesive deposition of “bucky gels”—viscous, non-volatile, CNT-containing mixtures—has been explored with ionic liquids and deep eutectic liquids,234,235 and related methods are used in the production of some commercial chemiresistive sensors.236

1.4. Performance Parameters

The promise of practical chemical sensors has motivated the constantly expanding research on CNTs. All analytical methods must possess the capability to provide quantitative, or in some cases, qualitative measurements. Chemical sensors, by definition, are devices with the capability to recognize and transduce the chemical information of the samples. In the simplest cases, the chemical information is the analyte concentration, and the read-out is a change in a readily measured signal. Ideally, a sensor is sensitive, selective, and stable. Achieving these figures of merit continues to be a challenge for the development of all sensors. Furthermore, chemical sensors are an alternative to large equipment in analytical lab and it is implicit that they are inexpensive, physically small (ideally portable), and robust under field conditions. CNT-based sensors are viewed as being well suited for these requirements. Additionally, qualities such as reproducibility, rapid response times, and low drift are demanded for practical sensors. We detail the requirements for practical sensors and its challenges from the chemical perspective. Central to our discussion are the interactions between functionalized (selector/receptor modified) CNTs and the analyte. This section will introduce and provide brief descriptions of the relevant figures of merit and how they are measured. This section will conclude with a discussion of challenges arising from the properties of CNTs.

1.4.1. Parameters of Performance and Figures of Merit: What they are and how to measure them?

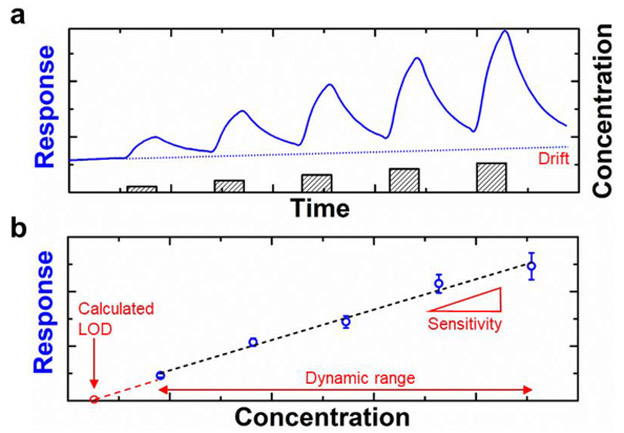

The sensing response curve describes how the devices respond to the exposure of the analyte as a function of time. Figure 12a illustrates a hypothetical curve when the device is exposed to increasing concentration of the analyte. The choice of the architecture of the sensing device will govern the type of signal measured by the sensor. The sensing traces are often reported as the relative changes in measured resistance (R), current (I), conductance (G = I / V; the symbol is not to be confused with Gibb’s free energy), capacitance (C), power gain (RFID), and resonant frequency (f0) of the device vs. time. Different conventions have been adopted for plotting these measurements—most popularly normalized differences ΔX/X0, X/X0, or simply ΔX (where X = R, I, G, C, or gain). For example, the change in conductivity (–ΔG/G0) is calculated by observing the normalized difference in the current before (I0) and after (I) the exposure to the analyte using Equation 1:

| Equation 1 |

Figure 12.

Hypothetical sensing response curve (a) and calibration curve (b) of a sensor exposed to increasing concentration of the analyte. Adapted with permission from Ref. 35. Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

The calibration curve (Figure 12b) shows the relationship between the response of the sensor and the concentration of the standard solution.237 The standard solutions for the analyte should be carefully chosen to cover the relevant concentration range. Sensitivity is defined as the capability to discriminate small differences in concentration or mass of the analyte. In other words, sensitivity of the sensor is the slope of the calibration curve. The range of the concentration of the standard solution measured for the calibration curve constitutes the dynamic range; the range of which the signal is linearly proportional to the concentration is the linear range.238

Limit of detection (LOD) is the lowest amount of an analyte in a sample which can be detected with reasonable certainty. The theoretical or calculated LOD, as established in literature,239–241 is determined as the concentration that corresponds to the signal at three standard deviations of noise above the baseline, using the calibration curve. Briefly, the root-mean-square noise (rmsnoise) of the sensors is first calculated as the deviation of the sensing response curve from the appropriate polynomial fit. The LOD is then calculated using Equation 2:

| Equation 2 |

The slope in Equation 2 is the linear regression fit of the sensor response vs. concentration curve (slope of the calibration curve). The drive for achieving lower LOD is often governed by application-dependent requirements. These values for environmental safety are published by regulatory agencies. The ability to detect low concentration of the analyte is often coupled dynamic range of the sensors which describes the range of concentration the sensor can be calibrated. Sensors with low LOD often deviate from linearity at high concentrations as a result of saturation.

Selectivity of a single sensor is defined as the ability to discriminate the analyte of interest from other species within the sample.242 Specificity is also used to express selectivity: in a literal interpretation a specific sensor recognizes only the target analyte and no other compounds. Such ideal sensors are rare as a result of similarity between analytes and lack of perfect molecular recognition. Cross signaling, also known as cross reactivity, between sensors and analytes leads to a compounding of the signals and loss of selectivity. Selectivity is measured from the signals arising from the analyte and the possible interfering compounds separately with the assumption that there are no synergistic cooperative effects of multiple analytes and the sensor. The calibration curves (signal vs. concentration) of each is then compared. The ratio of the signals of the analyte to those of the interfering compounds defines the selectivity of the sensor. This method is operationally simple and generally adequately quantifies the desirable signal relative to possible cross signaling. However, it may overlook the competing effects between different compounds and the analyte. The second method comprises replicating the matrix (simple or complex) of the real-world samples in which the analyte is mixed with expected interfering compounds. In such case, the selectivity of the sensor can then be determined by the differences in signal of the analyte with and without the interfering agents.

Stability is defined as the capability of the sensors to produce repeatable outputs for an identical environment over time. To measure the stability of the sensors, repeated measurements should be taken over time or over many cycles of exposures to the analyte. In a more methodical method, full calibration curves are obtained for multiple devices over time. During the operational timeline of a sensor, issues regarding stability may arise from several sources, such as drift, hysteresis, and irreversibility. These issues are particularly prevalent in the development of sensors for highly reactive analytes. Drift is defined as the change in signal over time independent of stimuli. It remains one of the challenges to be solved for CNTs-based sensors. The common sources of drift can be identified as either the physical changes occurring to the selectors/receptors and the context of their interactions with the CNTs, very small changes in the positions of nanotubes that effect CNT-CNT junctions, or parasitic electrical effects including the electromotility of ions under small applied potentials. The perturbation of the sensing layer caused by gas flow, pressure differentials, and thermal rearrangements can lead to signal drift.33 Hysteresis is the difference between the output of the sensors when an analyte concentration is approached from an increasing and decreasing range. It is also influenced by the degree of irreversibility of the sensor, which is the background signal of the sensor before and after exposure to the analyte.

Lastly, the response and recovery times are important key factors when evaluating the performance of chemical sensors. The response time is defined as the time for the sensor to reach 90% of its steady state or maximum value upon an exposure to a given concentration of the analyte; while, the recovery time is measured as the time required for the sensor to recover to 10% of its peak value. Reversibility is coupled with recovery time as the extent to which the output can be restored after an exposure.

1.4.2. Specific Challenges on the Performance of CNT-Based Chemical Sensors

The last subsection provided definitions for evaluating the chemical sensor performance; we now introduce specific performance challenges for CNT-based chemical sensors. Significant effort has been applied to the development of practical CNT-based chemical sensors. However, many challenges still need to be addressed to realize many sensing applications.

Quality controls and reproducibility.

The quality and the purity of the CNTs often led to the differences in the sensing performance as reported by different research groups. For example, the differences in the performance can stem from the source/growth of CNTs,243,244 defect levels in the CNTs,245–249 or sensor fabrication.250,251 Obtaining high purity and specific size/helicity of the CNTs is a formidable task. Separation methods that produce high purity CNTs are inefficient and not readily scaled and thereby increase sensor costs. Establishing standardized baselines requires extensive characterization of the CNTs.

Operating temperature.

Room temperature operation is one clear advantage of CNT-based sensors over conventional chemiresistive sensors based on metal oxide semiconductors. Although operating at room temperature enables lower power consumption, it can lead to competing non-specific interactions. In this context, water sensitivity is an important parameter to be tested for practical CNT-based sensors. In addition, thermal stability of the selector/receptor-CNT composite should be tested for applications that would expose the sensors to elevated or fluctuating temperature.

Reversibility.

Strong interactions designed for ultra-trace analyte LOD can lead to slow off rates and prevent the sensor recovery in an analyte-free environment. Slow desorption of gas molecules can often be alleviated using thermal treatments or photoirradiation. These treatments, however, increase complexity (in both design and operational) and cost of the overall systems. Thus, intrinsic reversibility endowed from the interaction between the well-designed selectors and the analyte is generally preferred.

1.5. Theoretical Models

Theoretical models have been used extensively to understand and predict carbon nanotube behavior and properties. Specifically, computation on CNTs have been used to probe their electronic properties in pristine252 and deformed forms,253 thermal conductivity,254 elasticity,255–257 and flexibility.258–260 We direct interested readers to in-depth reviews on the thermal and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes261–264 and details of the computational methods.265–268 This section highlights theoretical models for analyte-carbon nanotube interactions. These studies are used to understand the experimental data generated in sensing experiments or to computationally design novel sensors.

The possibility of probing the sensing mechanism of carbon nanotube-based sensors with computational models has been demonstrated by Cho and coworkers.269 In this early work, the interactions between CNT and adsorbed gas molecules was investigated using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The carbon nanotube was represented as a carbon nanohoop with one-dimensional periodic boundary conditions along the tube axis. To investigate the adsorption-induced nanotube doping, the electronic and energy states of a tube with and without adsorbed molecules of NO2, NH3, CO, O2, and H2O were compared. Electron donation from the tube to the analyte was observed for NO2 and O2, while electron donation from analyte to the tube was observed for NH3. These findings were in agreement with published experimental results.21,270 Since this study, a large number of studies on adsorption of small gaseous molecules on CNT-systems have been reported. The binding energies determined through different computational methods range widely (e.g. for adsorption of NO2 on (10,0)-SWCNT binding energies from 0.92–18.6 kcal/mol), however the proposed sensing mechanisms are qualitatively consistent with the major sensing mechanism (e.g. adsorption of NO2 induces p-doping on the CNTs).21,38,63,269,271,272 Other sensing mechanisms that have been proposed for NO2 include chemisorption via formation of nitro- and nitrite-groups,61–63 changes in the density of states (DOS) of the CNT,270 electron localization effects,46 or changes in the dipole moment of NO2.273

The wide variety of results for the seemingly simple system of NO2 adsorbed on CNTs reveals the complexity of treating CNTs computationally. Challenges associated with their modelling include: (a) their large and conjugated π-system contains highly strained bonds which are inherently difficult to represent computationally,62 (b) the individual interaction energies between analyte and carbon nanotube are often very small and the resulting physisorbed states cannot be determined with great accuracy by DFT, and (c) the chirality of the CNT has a strong influence on its electronic properties which often complicates comparisons between computational studies or computational and experimental findings.274,275 Consequently, the choice of the computational method276 and length of the investigated CNT model277 can have large influences on the outcome of the theoretical study.

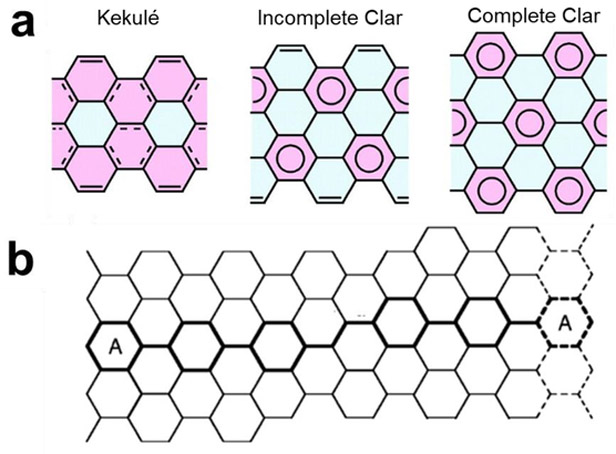

To create computationally tractable systems, studies have used periodic boundary conditions to model the quasi one-dimensional CNTs—a typical ratio of diameter to length is about 1:1000—which limits the selection of approximate exchange-correlation functionals and analysis methods. When truncated CNTs—with end states saturated with hydrogen atoms—are used, one runs into the risk of using a too small CNT size which cannot reflect the delocalized nature of the CNT electronic states accurately.277,278 It has become apparent that not only CNT length but also the shape of the “cut” determines computational outcomes of truncated CNT studies. Specifically, the theoretical description of truncated CNTs can be improved by taking the Clar sextet rule into account. The Clar valence bond theory, as postulated in 1964, describes polyaromatic hydrocarbons with both conventional two-electron π bonds and aromatic sextets (benzene). Clar demonstrated that the valence bond structure with the most aromatic sextets best models the reactivity of polyaromatic hydrocarbons and that structures possessing only aromatic sextets are especially stable (Figure 13).279 In CNTs, it has been shown that structures with the maximum amount of aromatic sextets for a given chirality and number of carbon atoms best describe the reactivity and geometry of CNTs and CNT-reactant studies.280–284 Accordingly, computational investigations employing “straight cut” CNT samples might misrepresent the reactivity of the studied model which might be the source of some inconsistencies in published results on CNT-analyte interactions. For detailed discussions on the Clar sextet rule in CNTs we refer the interested reader to key studies by Matsuo et al.,281 Baldoni et al.,278,283 and Ormsby et al.282,284

Figure 13.

(a) Schematic representations of Kekulé, incomplete Clar, and complete Clar networks. Kekulé structure infers a 1,3,5-cyclohexatriene-type cyclic conjugate system, and the Clar structure represents a benzene structure with equivalent C-C bond lengths. Nucleus-independent chemical shift coding: red, aromatic <−4.5; blue, nonaromatic >−4.5. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 281. Copyright 2003, American Chemical Society. (b) Planar representation of a chiral (6,5) CNT. Dashed lines represent replication of hexagons when the structure is rolled up to give the nanotube. The Clar unit cell is highlighted with thick lines. For (6,5) CNTs the Clar unit cell contains five aromatic sextets and one double bond. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 285. Copyright 2009, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Keeping the stated challenges in mind, we highlight several applications where computational studies have successfully predicted or explained experimental behavior of CNT-based chemical sensors. Intrinsic doping of nanotubes with heteroatoms can be used to increase the sensitivity and selectivity of the CNTs towards electron accepting or donating analytes. Accordingly, n-type dopants like nitrogen,286–289 phosphorous290, or sulfur291 deliver higher binding energies and stronger charge transfer between electron-accepting analytes like NO2 and the CNT. Similarly, p-type dopants like boron,286,288,292–296 and aluminum287,289,290,297,298 show strong binding with electron donating analytes like NH3, formaldehyde, cyanides or hydrogen halides.

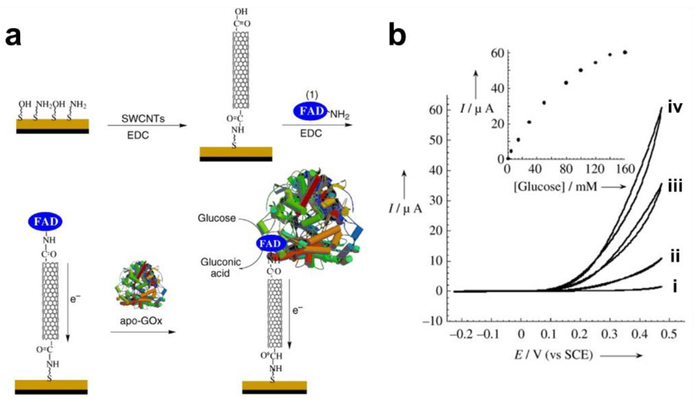

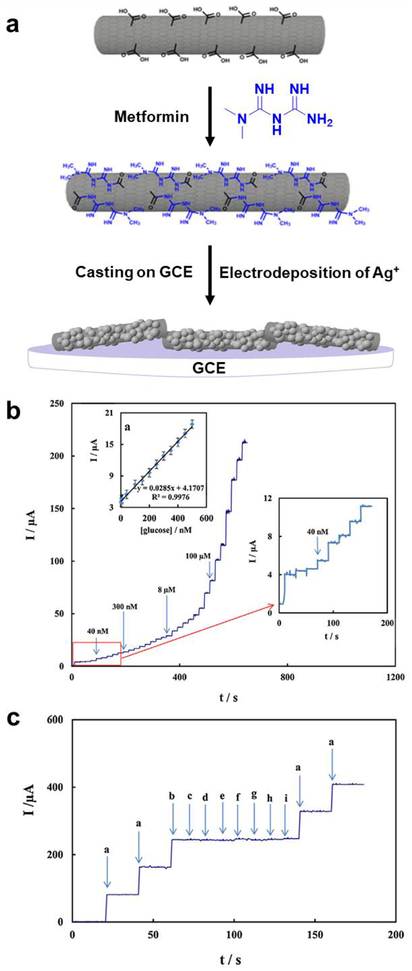

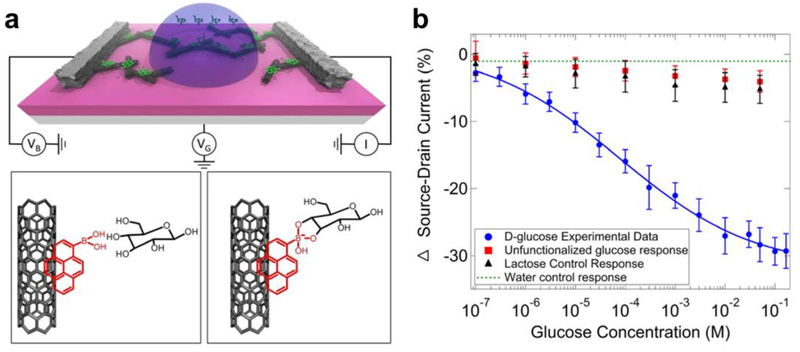

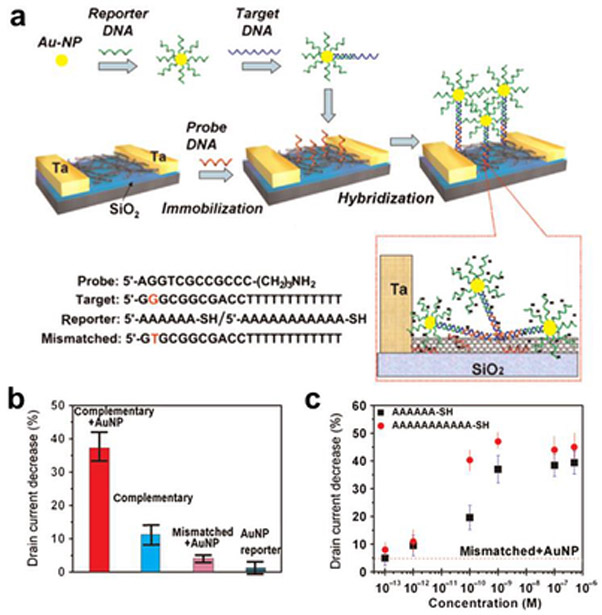

Tubes decorated with a single metal atom or a metal cluster have been studied extensively using computational methods. A number of groups reported computational studies that probe the adsorption mechanism and reactive behavior of gaseous analytes on metal-decorated CNTs298–304 or CNTs decorated with metal nanoparticles (NPs).45,46,137,305–309 Metal-analyte combinations with higher binding energies, stronger charge transfer or stronger perturbations in the density-of-states are believed to lead to stronger signals in sensing studies. Based on these computational findings, well-informed matching between selectors and CNTs are possible.