Abstract

Background:

Interventions to improve physical and psychological outcomes in recipients with an initial implantable cardioverter (ICD) and their intimate partners are largely unstudied, though likely to have a major impact on adjustment to the ICD and general well-being.

Objective:

To report the primary outcomes of the Patient Plus Partner randomized control trial.

Methods:

In a two-group (N=301) prospective RCT, we compared two social-cognitive-based intervention programs [Patient Plus Partner (P+P) and Patient Only (P only)], implemented following initial ICD implant. The patient intervention, consisting of educational materials, nurse-delivered telephone coaching, videotape demonstrations, and access to a nurse via a 24/7 pager, was implemented in both groups. P+P also incorporated partner participation. The primary patient outcomes were symptoms and anxiety at 3 months. Other outcomes were physical function (SF-36, ICD shocks-patient); psychological adjustment (PHQ-9); relationship impact (DAS, OCBS-partner); self-efficacy and knowledge (SCA-SE, SCA-OE, KSA); and health care utilization (outpatient visits, hospitalizations), at hospital discharge, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-ICD.

Results:

For patients, P+P compared to P Only was more effective in improving symptoms (P=0.02), depression (P=0.006), self-efficacy (P=.02), outcome expectations (P=0.03), and knowledge (P=0.07). For partners, P+P was more effective in improving partner caregiver burden (P=0.002), self-efficacy (P=0.001) and ICD knowledge (P=0.04).

Conclusion:

An intervention that integrated the partner into the patient’s recovery following an ICD improved outcomes for both. Beyond survival benefits of the ICD, intervention programs designed to address both the patient and their partner living successfully with an ICD are needed and promising.

Keywords: Sudden cardiac arrest, ICD, clinical trial, self-efficacy, telephone intervention, partner, anxiety, depression, health care use

INTRODUCTION

Research points to the important reciprocal influences that patients and partners have on one another’s recovery experiences after a cardiac event [1]. However, interventions designed to impact outcomes of both patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and their intimate partners, have not been systematically tested. Given the family stress caused by life-threatening illness and the ever-increasing number of ICDs being implanted worldwide [2], interventions are needed that are timely, both patient and partner-relevant, and integrated in a manner that improves patient recovery. In our past research, we demonstrated that intimate partners of recent ICD recipients reported better physical health than the patient, but their health declined during the first year post-ICD. Intimate partners also reported significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression over the first 12-months, higher than patients themselves. Following ICD implantation, partners consistently reported high caregiving demands and a corresponding lower level of satisfaction with their relationship with the patient [3,4]. Partners also note that important information and support was typically not available to them in outpatient settings.

We previously reported outcomes of a patient-focused self-efficacy intervention following an initial ICD implant after successful resuscitation from sudden cardiac arrest [5,6]. At the conclusion of the intervention, we interviewed patients to determine essential elements of the intervention. Most study participants wanted more telephone contact with the nurse, and would have liked an accompanying videotape to demonstrate important skills; many also desired more psychological support, and requested an intervention to better support their intimate partners. We incorporated these suggestions into our original patient only (P Only) intervention, and created an expanded Patient Plus Partner (P+P) intervention [6]. We then designed and conducted a prospective randomized clinical trial comparing outcomes between the two interventions, one that focused strictly on the ICD recipient (P Only) and one that was expanded to include the partner (P+P). We hypothesized that the expanded (P+P) intervention would result in better physical and psychological outcomes for both patients and partners, compared to the intervention that focused on the patient alone (P Only). Secondarily, we tested for differences in outcomes by ICD indication (e.g., primary vs. secondary prevention).

METHODS

Design

ICD recipients were randomized using a prospective 2-group blocked clinical trial (RCT) design. The strata were Charlson Co-morbidity score (<2 or ≥2) [10] and ICD indication (primary vs. secondary prevention). The RCT compared two intervention groups: 1) P Only, and 2) P+P during the first year post-ICD implant. Study outcomes were: a) physical functioning in the patient with an ICD (patient concerns/symptoms, general health, ICD shocks) and in the partner (partner concerns/symptoms, general health); b) psychological adjustment (anxiety and depression) in both the patient and partner; c) relationship impact for the patient (dyadic adjustment) and partner (dyadic adjustment, caregiver burden); d) self-efficacy for both the patient and partner, and e) health care utilization (outpatient visits, hospitalizations) for both patient and partner.

Sample and Setting

Study participants (N=301) were identified as first-time ICD recipients based on systematic screening at 12 acute care institutions in Washington, Oregon, Georgia, and North Carolina between 2010–2015. Identified patients and their partners were approached for study participation while hospitalized for the initial ICD implant. Written consent from both were required for study eligibility. Study procedures were approved by hospital-based IRBs and the academic IRB providing study oversight. Inclusion criteria were: 1) first ICD implant for primary or secondary prevention of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA); 2) ability to read, speak, and write English; 3) access to telephone for 1 year after ICD implant; and 4) having an intimate partner (spouse, lover, life partner or significant other) involved in a committed relationship with the patient. Exclusion criteria were: 1) clinical co-morbidities that impaired cognitive or physical function; 2) short BLESSED cognitive screening score > 6 [7]; 3) age < 21 years; 4) AUDIT-C score ≥ 4 for alcohol use [8]; and/or 5) ASSIST 2.0 score ≥ 4 for daily non-medical use of illicit substances [9].

Protocol and Interventions

After baseline data were collected, subjects were randomized to one of the two interventions (P Only or P+P). A computerized program generated a balanced randomization taking into account ICD indication, age, gender, and Charlson co-morbidity index [10]. All participants completed a battery of measurements at the same time periods, which included baseline (hospital discharge), and 1, 3, 6, and 12 month follow-ups, after which they received study-related intervention materials. All participants received usual care from their providers as well as interim telephone calls from study staff every 3 months to collect health care utilization information. A description of the study interventions and intervention fidelity is found in the supplementary materials.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes were assessed at baseline (hospital discharge), and at 1 (midway through the intervention, 3 (intervention completion), 6, and 12 months. Outcome measures, summarized in Table S1 (supplemental materials), were obtained for all patients and their respective partners in both intervention groups.

Analysis

Prior to the study, we estimated that a total of 300 patients would be needed to provide 80% power to detect group differences in the primary outcomes of physical functioning (PCA-symptoms) and psychological adjustment (STAI-anxiety) at 3 months, adjusted for an anticipated 15% dropout. All analyses were conducted using an intent-to-treat approach. Initially, we reviewed data for their distributional properties (means, variances, kurtosis) and potential outliers. Using chi square or t-tests, we tested for group equivalence in baseline demographic and outcome measures. Group intervention effects were tested for change in the primary outcomes from baseline to 3, 6 and 12 months using repeated analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA, SPSS 21.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), controlling for baseline outcome values, age, sex, Charlson score, ejection fraction %, and ICD indication (primary vs. secondary) [24]. ANCOVA F statistic indicated if the means between the two groups differed significantly. In conducting secondary comparisons, Bonferroni corrections were made to adjust for potential Type I error by dividing the α value by the number of additional comparisons (α/N) made in each outcome category by timeframe. Statistical significance was defined at α ≤ 0.02, 2-tailed. Intervention effects were also examined by indication for ICD implantation (primary vs. secondary prevention).

RESULTS

Participants

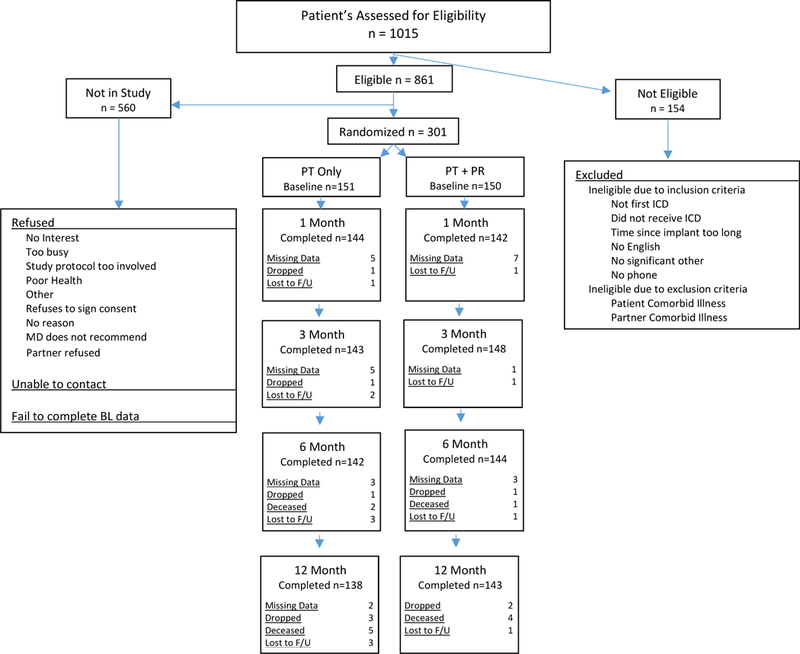

Over the five year study, 1051 patient-partner pairs were approached for study participation, of these 861 were eligible (Figure 1). The patient who received an ICD was the “index case” for study referral. Of the 861 eligible patients, 301 patient-partner pairs met eligibility criteria and were randomized to one of the two study groups: 151 pairs to the P Only, and 150 to the P+P intervention. Of these, 92% of patients in the P Only 95% of patients in the P+P group completed 12-month assessments. The follow-up rate over 12 months for partners was similar to that of patients in both study groups (91% of partners in P Only; 94% of partners in P+P).

Figure 1:

Consort Diagram

Patients

Study patients in both P Only and P+P groups averaged 64.14±11.9 (range 26–93) years, had a Charlson co-morbidity score of 2.29 ± 1.49 and a body mass index (BMI) of 29.57 ± 6.2. The majority were male (73.8%), Caucasian (91.0%), had some college education (50.8%), and were retired from work (43.2%) or disabled (15.6%), and received an ICD for primary prevention of cardiac arrest (58.9%) or secondary prevention of cardiac arrest (40.2%). At baseline enrollment, 37.5% of patients reported a sedentary lifestyle, 20.6% were taking anti-depressant medications, 11.0% were taking anti-anxiety medications, and 13% were current smokers (Table 1 and Table S2 in supplemental materials).

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients and Partners by Study Group

| P Only Group n = 151 | P+P Group n = 150 | Comparison Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | X2 , P-value | |

| PT Gender | X2 = 1.98, p = .16 | ||

| Female | 45 (29.8) | 34 (22.7) | |

| PR Gender | X2 = 2.39, p = .12 | ||

| Female | 106 (70.2) | 117 (78.0) | |

| PT ICD Indication | X2 = 03, p = .87 | ||

| Secondary | 60 (39.7) | 61 (40.7) | |

| PT Race/Ethnicity | X2 = 4.35, p = .36 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.7) | |

| PR Race/Ethnicity | X2 = 7.17, p = .13 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 (4.0) | 3 (2.0) | |

| Annual Income | X2 = 2.98, p = .70 | ||

| Not willing to answer | 3 (2.0) | 4 (2.7) | |

| mean ± sd | mean ± sd | T-test, P-value | |

PT=patient, PR=partner, BMI=body mass index, EF=ejection fraction, X2=Chi square.

Partners

Study partners in both P Only and P+P groups averaged 62.46±12.4 (range 28–91) years, had a Charlson co-morbidity score of 0.72±1.08 and a BMI of 28.9 ± 6.5. The majority were female (74.1%), Caucasian (88%), had some college education (39.9%), and were retired from work (40.5%) or disabled (6%). At baseline enrollment, 31.3% of partners reported a sedentary lifestyle, 25.6% were taking anti-depressant medications, 18.9% were taking anti-anxiety medications, and 12.3% were current smokers. (Table 1, and Table S2 supplemental materials).

By comparison, patients and their partners in P Only and P+P groups did not differ on many baseline factors. However, patients were less likely to be actively employed and their partners more likely to be taking antidepressant medications in the P Only than P+P group; whereas ASSIST recreational drug use was higher among patients and partners in the P+P group.

Intervention Fidelity

Over the 5 year course of the trial, the proportion of intervention elements delivered between treatment groups (98.5 ±1.2% in P Only and 97.5±2.3% in P+P), and the number of phone calls completed (98.5%±1.2 in P Only and 97.5%±2.3 in P+P) were similar. The cumulative time spent on telephone calls was significantly higher for those in the P+P group (mean±SD) (322±92 minutes vs 250±80 minutes, p=0.001), given that engaging both the partner and patient required more time to deliver the intervention. Partners who were randomized to P+P participated in an additional 291±77 cumulative minutes in the PTG intervention; 85% of whom completed all of the planned telephone calls. Most patients (97%) and partners (96%) were favorably impressed by the program and recommended that others participate in a similar one, if offered. Variability in intervention delivery by nurses within the intervention groups did not differ significantly, and the effect of the nurse on patient outcomes was not significant.

Outcomes Physical Function

Patient Physical Function.

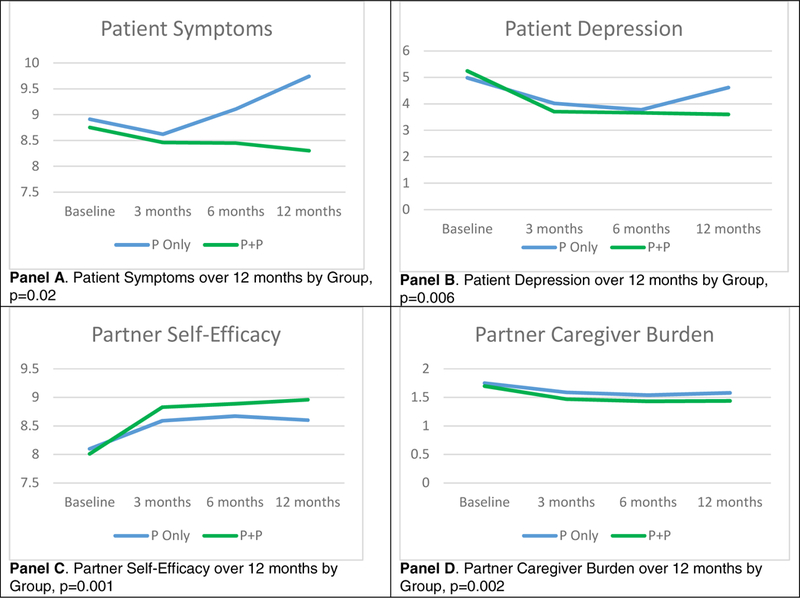

The frequency of self-reported PCA symptoms (primary outcome) fell significantly between the intervention groups (Figure 2A and Table S3, supplemental materials) at 12 months, with patients in P+P reporting fewer symptoms than those in P Only (P = 0.02). Fear of dying and distress reduced in both groups over time. Patients in both intervention groups reported lower levels of physical (PCS) than mental health (MCS) at study enrollment and throughout 12 months, with no statistically significant by group differences noted over 12 months. The number of ICD shocks by intervention group did not differ across time, ranging from 3 to 9% over the course of 12 months. Overall ICD shock rates were low, perhaps related to changes in ICD programming standards that occurred during the course of the study.

Figure 2.

Significant changes by study group for patients (Panel A & B) and partners (Panel C & D) across 12 months post-ICD implant.

Partner Physical Function.

As well, partners in both intervention groups reported lower levels of physical (PCS) vs. mental (MCS) health throughout the study, with no statistically significant by group differences noted. The number of physical symptoms reported by partners was lower than patients, and overall general health of partners was better than patients, from enrollment to final follow-up (Table S4, supplemental materials). The number of self-reported symptoms among partners did not differ significantly between the intervention groups over 12 months. ICD and health-related partner concerns declined in both intervention groups over time.

Psychological Adjustment

Patient anxiety (STAI) declined over time (primary outcome), with no significant differences observed between intervention groups (Table S3). However, for P+P vs. P Only, patient depression and depression severity (Figure 2B), significant reductions (P = 0.006 and 0.01, respectively) were noted at 12 months. Conversely, partner anxiety and depression remained relatively stable across the 12-months, without significant differences between P+P and P Only.

Relationship Impact

Patient Relationship Impact.

No statistically significant differences were observed over time for P+P vs. P Only with respect to overall dyadic adjustment or subscales of dyadic adjustment, including satisfaction, cohesion, consensus, or affectionate expression among study patients (Table S3). Nor were there significant group differences in patient sexual concerns, which were highest at hospital discharge and declined only modestly over time.

Partner Relationship Impact.

Similar to patients, there were no statistically significant intervention group differences among partners in overall or subscale measurement of dyadic adjustment, or sexual concerns (Table S4). Partner sexual concerns were higher than patients during the first 3 months post-ICD, and reduced to levels similar to those of patients at 6 months. For caregiving burden, however, partners in P+P compared to P Only reported significantly lower levels of caregiver burden and time spent in caregiving (Figure 2D). There were also trends toward reduction in caregiving difficulty reported by partners in the P+P compared to P Only at 3, 6, and 12 months, (P = 0.06, 0.07, and 0.06, respectively).

Self-Efficacy

Patient Self-Efficacy.

Self-efficacy was assessed using three indicators: self-efficacy for living with the ICD, outcome expectations after an ICD, and ICD knowledge. For specific aspects of self-efficacy for living with an ICD measured at 12 months, for P+P vs. P Only there were significantly higher levels in ICD function (P = 0.01), managing physical changes caused by the ICD (F=10.86, P = 0.001), relationship management related to the ICD (F=4.66, P = 0.03), and a trend for ICD safety (F=2.90, P= 0.09). For outcome expectations, a trend toward improvement for patients in P+P vs. P Only was observed at 3 months (F=3.34, P = 0.07), which was more pronounced at 6 months (F=5.06, P = 0.03), but declined by 12 months (F=0.36, P = 0.55). Patient ICD knowledge did not significantly differ over time for P+P vs. P Only, but was slightly higher in P+P at most points in time.

Partner Self-Efficacy.

For partner self-efficacy for living with the ICD, the P+P partner group reported significantly higher self-efficacy at all data collection points across 12 months (Figure 2C; Table S4). For outcome expectations, there were no significant group differences across time. Partner ICD knowledge was significantly higher in P+P vs. P Only at all time points over 12 months.

Health Care Utilization

Patient Health Care Utilization.

No statistically significant group differences in the frequency of patient hospitalization were noted over 1 year (Table S3). The patient hospitalization rate in both groups was 7.9% in the first month post-ICD, 20.6% at 1–3 months, 23.3% at 3–6 months, and 36.9% at 6–12 months. The average number of patient hospitalization days did not differ significantly by treatment group over 12 months, with total hospital days in both groups ranging from 2–6 days. Patients were hospitalized during the first year post-ICD for cardiac issues such as chest pain, heart failure exacerbation, cardiac arrhythmias, or ICD related reasons. However, patients in P+P had fewer outpatient visits over the course of the trial than those in P Only (2.54 vs. 3.09, P = 0.03; data not shown), which were most often ICD-related for both groups.

Partner Health Care Utilization.

No statistically significant differences in the frequency of partner hospitalizations were found between treatment groups during the follow-up year (Table S4). The hospitalization rate among partners in both groups was 2.7% during the first month, 3.3% from 1–3 months, 11.3% from 3–6 months, and 19.3% from 6–12 months, primarily for non-cardiac surgical procedures. The average number of hospitalization days in partners did not differ significantly by group over the 12 months, ranging from 2–5 days. No significant group differences were observed in the number of outpatient visits by partners over 12 months. On average, partners in both groups had 1 outpatient visit in each 3-month interval across the 12 months.

ICD Indication: Primary vs. Secondary Prevention

We conducted exploratory analyses to determine the effects of ICD indication (primary vs. secondary prevention) on differential benefit from the interventions (data not shown). There were marked baseline differences in the health of patients receiving an ICD for primary vs. secondary prevention reflected in higher Charlson co-morbidity scores (t = 2.88, P = 0.004), higher BMI (t = 2.17, P = 0.03), and lower ejection fraction (t = 8.64, P = 0.001) in the primary prevention group. Outcomes at 3 months showed that patients receiving an ICD for secondary prevention, had greater reductions in symptoms (PCA, F = 7.70, P = 0.006), better physical health (SF-36 PCS, F = 8.91, P = 0.001), and greater ICD knowledge (F = 5.02, P = 0.02). These changes were sustained at 12 months. Patients who received an ICD for primary prevention experienced more hospitalizations (F = 5.48, P = 0.04) over the first 3 months, but this difference was no longer apparent by 12 months. By comparison, ICD indication did not appear to have a robust or consistent influence on partner responses over the course of the trial.

DISCUSSION

The health impact of an ICD reaches far beyond rhythm management alone, extending to the functional and psychological aspects of daily living for both patients and their intimate partners. The importance of this RCT lies in being the first to establish such benefits from an intervention directed at both the patient and partner. We demonstrated that a P+P intervention is superior to a P Only intervention in reducing patient symptoms and depression, while improving self-confidence and ICD knowledge over time. The P+P intervention also proved to be superior to a P Only approach for the partner in reducing caregiver burden, while concurrently improving self-confidence and knowledge.

The intervention framework was based on Social Cognitive Theory [11], which is well suited for patients undergoing initial ICD implant and their partners. The ICD implant recovery period requires acquisition of new knowledge, behavioral skills and confidence to promote living successfully with an implanted device that is known to impact quality of life. A central component of this framework is self-efficacy, the belief in one’s capacity to engage in new behaviors in new situations. Enhancing self-efficacy as a means to facilitate health behavior change in CV disease has been studied extensively, demonstrating that self-efficacy influences cardiac-related lifestyle changes [25], motivation, and emotional reactions to stressful situations [26]. For patients recovering from acute myocardial infarction (MI) and heart surgery, self-efficacy have been positively associated with adherence to exercise programs [27–30]. Specifically, with coaching from health care providers, self-efficacy for walking and running generalized to activities such as weight lifting and sexual intercourse [31]. Higher self-efficacy in partners has been shown to predict long-term survival in patients with heart failure [32].

The content of the present intervention was tested earlier by our research group in patients undergoing initial ICD implant for secondary prevention [5,6]. The current study included patients who had received an ICD for secondary as well as primary prevention. Comparing study outcomes with our previous work [5,6], we note the following similarities in both studies: 1) patients report significant reductions in symptoms and improved self-efficacy and knowledge over 12 months, and 2) patient outcomes improved the most between hospital discharge and 3 months, and then stabilized over the remainder of the year.

Analyses based on primary vs. secondary indication demonstrated that reasons for receiving an ICD were associated with differential response to the intervention in patients. The patient group receiving an ICD for secondary prevention demonstrated a stronger response to the intervention, whereas there were few differences in partner responses to the intervention based on ICD indication.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study were its randomized design, careful and detailed attention to intervention fidelity, and low drop-out rates in both patient and partner groups. Few intervention programs for patients who get an initial ICD have been developed and tested, and until now none have included the partner. The interventions were delivered in the outpatient setting using telephone delivery, without the need for costly in person clinic visits. The interventions are being further individualized and developed for implementation into routine clinical care.

Though randomized, this trial was not blinded. Study outcomes were analyzed without knowledge of the subject’s group assignment. The study design did not include a true patient control group for comparison against a patient intervention group. However, the trial did include a partner usual care group. Some study outcomes relied on self-report. In anticipation of this limitation, individuals were excluded from study participation if they had cognitive deficits, were in extremely poor physical health after ICD implant, or lacked a intimate partner who was willing to participate. Study results pertain principally this population. Finally, while patients in the P Only group were asked not to share intervention content with their partners, we had little control over partner exposure to the written intervention content. However, partner participation in the telephone portion of the P Only intervention was monitored to ensure that partners did not participate in the weekly calls.

CONCLUSIONS

A telephone delivered self-efficacy based intervention that included both the patient and the intimate partner following implantation of an initial ICD, resulted in significant reductions in patient symptoms and depression, with higher self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and knowledge over the P only intervention. Benefits to the partner included a reduction in caregiver burden and improved self-efficacy and knowledge to care successfully for the patient with an ICD. Post-hospital based intervention programs established for those with an ICD should include both the patient and their intimate partner in education, support, and home care management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

NIH, NHLBI R01HL086580–01A2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinicaltrials.gov:

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Cynthia M. Dougherty, University of Washington School of Nursing.

Elaine A. Thompson, University of Washington School of Nursing.

Peter J. Kudenchuk, University of Washington School of Medicine, Division of Cardiology.

References

- 1.Van Horn E, Fleury J, Moore S. Family interventions during the trajectory of recovery from cardiac event: an integrative literature review. Heart Lung 2002; 31:186–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munir MB, Alqahtani F, Aljohani S, Bhirud A, Modi S, Alkhouli M. Trends and predictors of implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation after sudden cardiac arrest: Insight from the national inpatient sample. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018. January 9. doi: 10.1111/pace.13274. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougherty CM, Fairbanks AM, Eaton LH, Morrison MK, Kim MS, Thompson EA. Comparison of patient and partner quality of life and health outcomes in the first year after an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). J Behav Med 2016, 39:94–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dougherty CM, Thompson EA. Intimate partner physical and mental health after sudden cardiac arrest and receipt of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Res Nursing Health 2009; 32:432–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougherty CM, Thompson EA, Lewis FM. Long term outcomes of a nursing intervention after an ICD. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2005; 28:1157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dougherty CM, Lewis FM, Thompson ET, Baer, JD, Kim W. Short term efficacy of a telephone intervention after ICD implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol, 2004; 27:1594–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly participants. British J Psychia 1986;512:797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C). Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Assist Working Group. The Alcohol, smoking, and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Development, reliability, and feasibility. Addict 2002; 97:1183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psych Rev 1977; 84:191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty CM, Benoliel JQ, Bellin CM. Domains of nursing intervention after sudden cardiac arrest and automatic internal cardioverter defibrillator implantation. Heart Lung 2000; 29:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougherty CM, Pyper GP, Benoliel JQ. Domains for nursing intervention for intimate partners of sudden cardiac arrest survivors. J of Cardiovac Nurs 2004; 19:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougherty CM, Thompson EA, Kudenchuk PJ. Development and Testing of an Intervention to Improve Outcomes for Partners following Receipt of an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) in the Patient. Adv Nurs Sci 2012, 35:359–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins LS. Quality of life in patients of sudden cardiac death entering treatment In Dunbar SB, Ellenbogen KA, Epstein AE. Sudden Cardiac Death: Past, Present, and Future. Armonk: NY: Futura Publishing;1997,289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE. Standards for validating health measures: Definitions and content. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (self-evaluation questionnaire). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Int Med 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinke EE, Gill-Hopple K, Valdez D, Wooster M. Sexual concerns and educational needs after an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Heart Lung 2005: 34:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinke EE. Sexual concerns of patients and partners after an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2003; 22:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spanier GB Assessing dyadic adjustment: New Scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam 1976; 38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakas T, Austin JK, Jessup SL, Williams LS, Oberst MT. Time and difficulty of tasks provided by family caregivers of stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs 2004, 36: 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougherty CM, Thompson EA, Johnston SA. Reliability and validity of the self-efficacy expectations and outcome expectations after ICD implantation scales. Appl Nurs Res 2007; 20:116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kepple G, Wickens TD. Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook (4th Ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/ Prentice Hall, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psych 1982; 37:122–147. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izawa KP, Watanabe S, Omiya K, Hirano Y, Oka K, Osada N, Iijima S. Effect of the self-monitoring approach on exercise maintenance during cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehab 2005; 84:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor CB, Bandura A, Ewart CK, Miller NH, DeBusk RF. Exercise testing to enhance wives confidence in their husbands cardiac capability soon after clinically uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction. Am J Card 1985; 55:635–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R, Fuhrmann B, Kiwus U, Voller H. Long term effects of two psychological interventions on physical exercise self-regulation following coronary rehabilitation. Int J Behav Med 2005; 12:244–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson D & Keller C. Relationships among health beliefs, self-efficacy, and exercise adherence in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart Lung 1992; 21:58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll DL. The importance of self-efficacy expectations in elderly patients recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. Heart Lung 1995; 24:50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Farrell P, Murray J, Hotz SB. Psychologic distress among spouses of patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. Heart Lung 2000; 29: 97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC, Cranford JA, Sonnega JS, Nicklas JM. Beyond the ‘self’ in self-efficacy: Spouse confidence predicts patient survival following heart failure. J Fam Psychol 2004;18:184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.