Abstract

Background

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) -Richardson’s Syndrome and Corticobasal Syndrome (CBS) are the two classic clinical syndromes associated with underlying four repeat (4R) tau pathology. The PSP Rating Scale is a commonly used assessment in PSP clinical trials; there is an increasing interest in designing combined 4R tauopathy clinical trials involving both CBS and PSP.

Objectives

To determine contributions of each domain of the PSP Rating Scale to overall severity and characterize the probable sequence of clinical progression of PSP as compared to CBS.

Methods

Multicenter clinical trial and natural history study data were analyzed from 545 patients with PSP and 49 with CBS. Proportional odds models were applied to model normalized cross-sectional PSP Rating Scale, estimating the probability that a patient would experience impairment in each domain using the PSP Rating Scale total score as the index of overall disease severity.

Results

The earliest symptom domain to demonstrate impairment in PSP patients was most likely to be Ocular Motor, followed jointly by Gait/Midline and Daily Activities, then Limb Motor and Mentation, and finally Bulbar. For CBS, Limb Motor manifested first and ocular showed less probability of impairment throughout the disease spectrum. An online tool to visualize predicted disease progression was developed to predict relative disability on each subscale per overall disease severity.

Conclusion

The PSP Rating Scale captures disease severity in both PSP and CBS. Modelling how domains change in relation to one other at varying disease severities may facilitate detection of therapeutic effects in future clinical trials.

Keywords: Corticobasal Syndrome, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, PSP Rating Scale, Interactive Visualizations, Predictive Models

Introduction

The classic form of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), also known as Richardson’s syndrome (PSP-RS), is a progressive neurodegenerative disease historically classified as an atypical parkinsonism. The prevalence of PSP in the general population is thought to be approximately 1–7 persons per 100,000 [1,2].

Corticobasal syndrome (CBS) is an atypical parkinsonism syndrome now called corticobasal degeneration (CBD). Like PSP, insoluble deposits in neurons and glia of CBD are composed primarily of 4R tau. Clinically, CBS and PSP frequently overlap, and both disorders share common genetic risk factors such as the H1/H1 haplotype.[3]

Currently, no disease-modifying therapies are available for patients with PSP,[4,5] and no clinical trials have shown efficacious treatment of PSP or CBS. Agents that target tau protein abnormalities are in human clinical trials.[6] Analytical understanding of the spectrum of 4R tauopathy symptom decline can facilitate clinical development of PSP therapies and the design of combined 4R tauopathy trials enrolling both PSP and CBS patients.

The PSP Rating Scale (PSPRS) is a well-validated, multi-domain clinical rating scale used to measure disease severity and progression in PSP. It was a primary outcome measure in a number of large multicenter clinical trials and natural history studies.[7–9] The PSPRS comprises a range of sub-scales that capture key clinical features of PSP, including ocular and limb motor function, gait abnormalities, bulbar impairments, and cognitive and behavioral changes.

In this study, cross-sectional data from three clinical trials and one natural history study are used to model the probability that a given subscale (e.g. gait, ocular) score will be mildly to severely impaired over the range of total PSPRS scores, as a surrogate measure for time and disease progression. For example, if a patient has a total PSPRS score of 42 (moderately impaired) the analysis will show which subscale impairments are most likely to explain this score, and which subscales are most likely to change as (s)he progresses over time. An improved understanding of the PSPRS will facilitate the design and analysis of clinical trials aimed at slowing progression in PSP/CBS.

The results from these analyses are presented as interactive visualizations, to demonstrate the full scope of symptom manifestations over increasing disease severity (measured using a variety of common rating scales), across a broad population of patients with PSP and CBS. This provides a more comprehensive picture of probable disease progression than static graphics or descriptions.

Methods

Data

All analyses were conducted on previously collected clinical trial data from 3 completed studies and 1 ongoing study. The 3 completed interventional studies did not demonstrate efficacy greater than placebo, and the drugs are no longer being developed in these indications. However, these studies provide a large systematic collection of data for this rare disease population. Baseline data for all available patients providing a PSP Rating Scale score were included from four sources:

AL-108–231 (Clinicaltrials.gov, number NCT01110720) - A trial for davunetide in patients with PSP [8]; data for 304 patients were obtained over 52 weeks.

PROSPERA (Clinicaltrials.gov, number NCT01187888) - Evaluating the safety, tolerability, and therapeutic effect of rasagiline on symptom progression in 44 patients with PSP over a year.[9]

TAUROS (Clinicaltrials.gov, number NCT01049399) - Assessing the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tideglusib, as potential treatment for PSP.[7] The 52-week study enrolled 146 PSP patients with mild-to-moderate disease.

4RTNI (Clinicaltrials.gov, numbers NCT01804452 and NCT02966145) – A 12-month natural history study to identify the best methods of analysis for tracking PSP and CBS over time; 73 PSP patients and 49 CBS patients are included.

Studies followed approximately the same inclusion criteria, requiring a probable diagnosis of PSP, similar age ranges, and a requirement for patients to be able to walk independently or with minimal help. TAUROS, AL-108–231, and 4RTNI did not specify an inclusion range on the PSPRS, whereas PROSPERA required patients to have a baseline score of less than 40 as they were targeting a milder subset of diagnoses. 4NRTI also included CBS patients with a probable CBD diagnosis [10].

All patients provided written informed consent prior to study drug administration or any study procedure obtained. All study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

PSP Rating Scale

The PSP Rating Scale (PSPRS) comprises 28 items in 6 categories (range of score 0–100) as reflected below: History (daily activities), Mentation, Bulbar, Ocular Motor, Limb Motor, and Gait/Midline [11]. As the possible range of scores differs for each domain, they were normalized and expressed as a percentage of the total possible score for that domain.

Statistical Methods

Proportional odds models (POMs) for ordered categorical data at baseline were used to model each PSPRS subscore, with the PSPRS subscores as the dependent variables and the total score as the covariate for all PSP patients. This method uses a logistic link function to model cumulative probabilities of each PSPRS subscore. Each model produced probabilities for each subscore level and every possible total score [12,13].

Proportional odds model curves were generated for each subscore, showing the probability of that impairment starting (i.e. increasing beyond 25% of the maximal subscore score). Non-impairment is defined as a subscore less than 25% of the maximal subscore (however, non-impairment on a scale can still be associated with mild signs or examination findings). These curves do not represent a change over time, but rather give a cross-sectional likelihood for the subscore at each level of PSPRS total score, as measured at the baseline visit. Here, the total PSPRS score becomes a surrogate for progressed time on the disease scale to identify the sequence in which abilities decline. Confidence intervals 95% were computed for the proportional odds model via a bootstrapping method with 1000 resampling iterations and are shown in the interactive online tool (Appendix 1).

595 patients with PSP across the four studies combined were analyzed, and compared to the probable disease progression for the 49 patients with CBS.

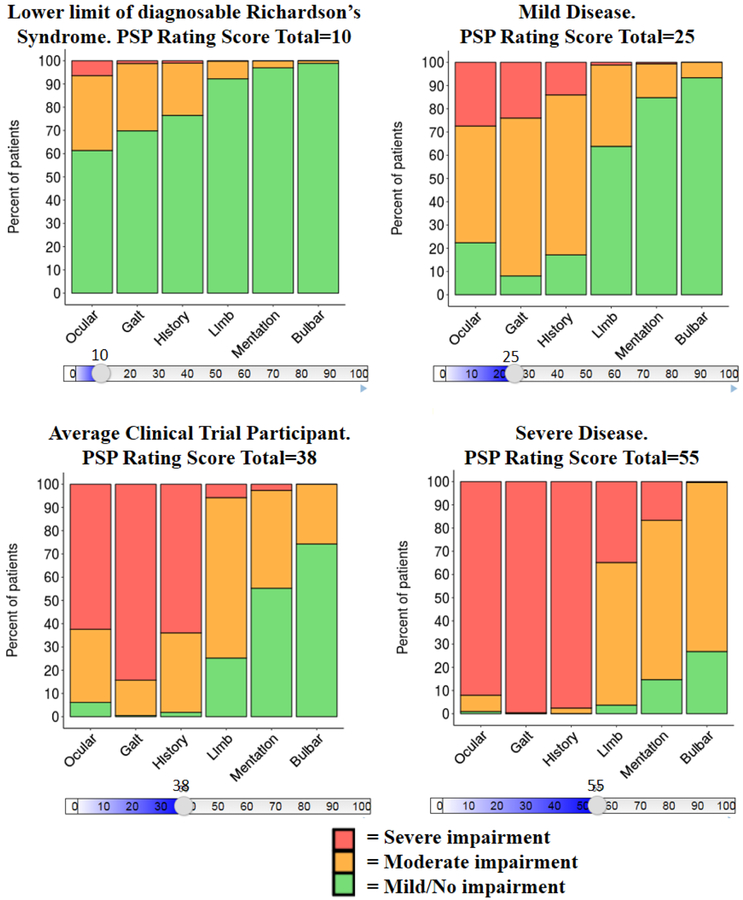

Bar charts were created to demonstrate the probability of no/mild, moderate, and severe impairment for each domain subscale. It should be noted the graphics represent the same cross-sectional modelling but the curves only show when impairment begins (i.e., when the 25% threshold is breeched for each domain), whereas the interactive visualization shows probability of being within 1 of the 3 categories of impairment [0–25%=no/mild (i.e. prior where start of impairment is defined in the POM curve), 25–50%=moderate, 50%+=severe].

A slider can then be used to assess the probable progression over time for any given PSP total score extrapolated for the entire 0 to 100 PSP Total Score range (interactive bar chart, Appendix 1).

The analysis was repeated for each of the subscores on the Clinical Global Impression of Disease Severity (CGIds) and SEADL scales separately.

As a complementary analysis to assess the predictive nature of the cross-sectional POM modelling, the observed longitudinal analysis over 12 months was conducted using placebo PSP Richardson’s Syndrome patient data from AL-108–231/Davunetide (0, 6, 13, 26, 39 and 52 weeks) and 4RTNI (0, 26 and 52 weeks). Change from baseline for each PSPRS domain was calculated at each time point and analysed using a mixed-effects model repeated measures (MMRM). The mixed model included study and baseline as fixed effects and time point as a repeated effect within patient. To allow comparison across subscales the effect size (change over time/modelled SD) was reported. This analysis was not repeated for CBS patients due to small longitudinal sample (n=24 at 52 weeks).

Statistical analyses and baseline data integration were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Further, POM analyses were performed using the VGAM (0.9–0) package within R 3.3.0. [14,15] Interactive and exploratory data visualization was performed using the Shiny package within R 3.3.0 [16].

Results

As shown in Table 1, the age range and gender split were similar across all trials; additionally, participants were predominantly Caucasian. In the 3 studies enrolling mild to moderate PSP patients (AL-108–231, 4RTNI, and TAUROS), mean baseline domain subscores were roughly equivalent (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Baseline Summary Statistics for Each Study

| AL-108–231: Davunetide | 4RTNI: No Drug (PSP) | 4RTNI: No Drug (CBS) | PROSPERA: Rasagaline | TAUROS: Tideglusib | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Total (Drug:Placebo) | 153:151 | 0:73 | 0:49 | 22§:22 | 115:31 |

| Age | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 67.6 ± 6.55 | 70.1 ± 7.56 | 66.4 ± 6.76 | 68.3 ± 5.44 | 68.2 ± 7.00 |

| Median (Range) | 68 (45 – 84) | 70 (55 – 86) | 66 (53 – 82) | 69 (50 – 77) | 68 (51 – 85) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female, N (%) | 142 (47) | 40 (55) | 29 (59) | 23 (52) | 62 (43) |

| Race | |||||

| White, N (%) | 266 (88) | 62 (85) | 40 (82) | 44 (100) | 140 (96) |

| PSP Rating Scale Total Score | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 39.7 ± 11.03 | 38.0 ± 16.44 | †27.7 ± 12.20 | *29.1 ± 6.77 | 38.8 ± 12.08 |

| Median (Range) | 39 (9 – 77) | 37 (10 – 86) | 25 (7 – 63) | 28 (17 – 39) | 39 (9 – 67) |

| MMSE Total Score | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 26.3 ± 3.47 | 24.9 ± 4.90 | 24.1 ± 6.37 | ||

| Median (Range) | 27 (15 – 30) | 26 (1 – 30) | 27 (5 – 30) | ||

| SEADL | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 52.2 ± 21.73 | 60.5 ±25.91 | 59.3 ± 21.11 | †78.4 ± 10.10 | 55.4 ± 21.08 |

| Median (Range) | 50 (10 – 100) | 70 (10 – 90) | 60 (10 – 90) | 80 (40 – 90) | 50 (10 – 100) |

| CGIds | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 0.90 | 4.0 ± 0.92 | 3.8 ±0.73 | 4.2 ± 0.93 | |

| Median (Range) | 4 (2 – 6) | 4 (2 – 6) | 4 (3 – 5) | 4 (2 – 6) | |

| PSP Rating Scale Bulbar | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 1.47 | 2.9 ± 1.70 | †1.3 ± 1.23 | 2.4 ± 0.97 | 2.8 ± 1.57 |

| Median (Range) | 3.0 (0 – 7) | 3.0 (0 – 6) | 1.0 (0 – 4) | 2.0 (0 – 4) | 3.0 (0 – 8) |

| PSP Rating Scale Gait | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.4 ± 3.85 | 10.4 ± 5.35 | †6.7 ± 5.29 | *6.7 ± 1.86 | 10.1 ± 4.22 |

| Median (Range) | 10.0 (0 – 20) | 10.0 (0 – 20) | 6.0 (0 – 19) | 6.5 (4 – 11) | 10.0 (0 – 19) |

| PSP Rating Scale History (Daily Living) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.7 ± 3.38 | 8.4 ± 4.15 | †6.3 ± 3.05 | *6.7 ± 2.32 | 8.1 ± 3.01 |

| Median (Range) | 9.0 (0 – 20) | 8.0 (1 – 20) | 6.0 (1 – 16) | 7.0 (2 – 11) | 8.0 (1 – 16) |

| PSP Rating Scale Limb Motor | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.75 ± 2.31 | 5.1 ± 2.73 | †7.9 ± 3.15 | *3.0 ± 1.41 | 5.1 ± 2.36 |

| Median (Range) | 4.0 (0 – 14) | 5.0 (1 – 14) | 7.0 (2 – 15) | 3.0 (0 – 6) | 5.0 (0 – 12) |

| PSP Rating Scale Mentation | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 2.58 | 3.6 ± 2.45 | 2.9 ± 2.19 | 2.8 ± 1.38 | 3.3 ± 2.62 |

| Median (Range) | 3.0 (0 – 15) | 3.0 (0 – 13) | 2.5 (0 – 11) | 3.0 (0 – 5) | 3.0 (0 – 12) |

| PSP Rating Scale Ocular Motor | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.4 ± 2.93 | 7.5 ± 3.97 | †2.6 ± 2.72 | 7.5 ± 2.06 | 9.4 ± 3.28 |

| Median (Range) | 10.0 (2 – 15) | 8.0 (1 – 16) | 2.5 (0 – 11) | 7.0 (4 – 13) | 10.0 (1 – 15) |

Abbreviations: CBS, corticobasal syndrome; CGIds, Clinical Global Impression of Disease Severity; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; SD, standard deviation; SEADL, Schwaab and England Activities of Daily Living.

Significant differences between PROSPERA and all 3 other PSP studies; *p<0.05, †p<0.001.

Significant differences between CBS and pooled mild-moderate PSP studies; *p<0.05, †p<0.001.

Note: At time of writing, for the 4RTNI study, CGIds and SEADL baseline values are available only for 50 PSP patients (out of 73), and 30 CBS patients (out of 49). § Baseline data for patients on Rasagaline not available to author.

The PROSPERA trial enrolled patients with less severe PSP; the inclusion criteria specified a PSPRS total score below 40. The mean PSPRS score in PROSPERA was lower (29.1) than in other trials (38.0 to 39.7). All PROSPERA subscores, other than Ocular Motor, were less severe than the subscores of PSP patients enrolled in AL-108–231, 4RTNI, or TAUROS

The AL-108–231, 4RTNI, and TAUROS trials have similar baseline scores for CGlds and SEADL.

For CBS patients (enrolled in 4RTNI only), Ocular Motor, Gait, History, and Bulbar domain subscores were significantly lower than for PSP patients enrolled in the mild-to-moderate PSP studies (4RTNI, AL-108–231, and TAUROS). The mean Ocular Motor subscore stands out as being substantially lower in patients with CBS than with PSP: 2.6 for CBS, compared with 7.5–9.4 for mild-to-moderate PSP. By contrast, Limb Motor mean subscores were significantly higher in patients with CBS than mild-to-moderate PSP (7.9 versus 4.7–5.1).

For the average PSP patient (Table 1) entering a clinical trial, they had a >80% chance of pre-existing impairment in the Ocular, Gait, Midline, and History subscores, a 50% chance of pre-existing Limb Motor impairment, and a <30% chance of Mentation and/or Bulbar impairment (Figure 1, bottom left panel). Even in a mild presentation (PSPRS total score=25), a patient has a 78% likelihood of enrolling with an existing greater than mild ocular impairment, this is expected because the PSP enrolment criteria for all the studies required individuals to have at least mild ocular motor impairment.

Figure 1. Proportional Odds Models - Sequence of Decline of PSP Rating Scale Subscores for Mild, Moderate, and Severe Impairment as PSP Rating Scale Total Score Worsens - 4 PSP Studies Combined.

Note: Four snapshots of PSP disease progression using the online graphic; each graphic shows the percent of patients that are contained within each category of domain impairment (e.g. no/mild, moderate, or severe). Abbreviation: PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy. Link to online version:

Post-enrollment, many patients will then likely develop impairment in the Gait/Midline and History (daily living) domains, which continue to decline at a faster rate than their Ocular score. This switch from Ocular being the most prominent domain to Gait/Midline and History being the most prominent domains occurs when the average patient reaches a PSPRS total score of ≥25.

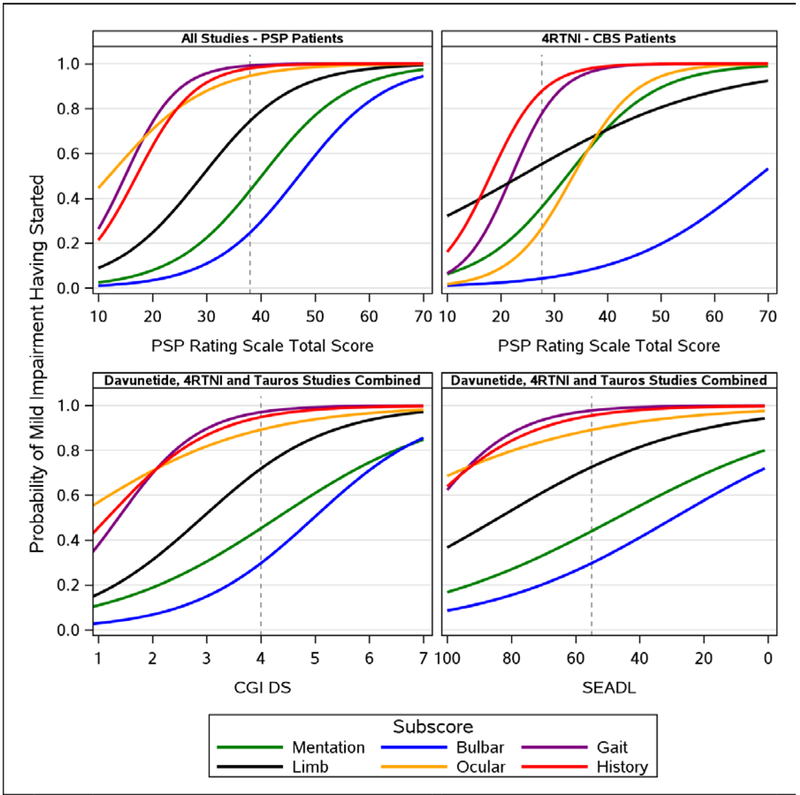

Figure 2 (top left) shows probability of decline of symptoms in a PSP Richardson’s Syndrome population. The subscore on the left is, on average, the earliest to show deterioration at the lower end of PSP total scores observed in the study (10 out of 100). For example, the probability of some impairment in the ocular scale is 0.39, whereas in the bulbar scale there is negligible probability (<0.02) of impairment. By visually inspecting the curves, an order of probable progression of subscores can be determined. It can be observed that as the PSPRS total score worsens (i.e. from 10 points onwards), a patient would expect to see Ocular Motor impairment first, followed by impairment in Gait and History, then Limb Motor skills, Mentation, and finally Bulbar.

Figure 2. Proportional Odds Models – Probability of Start of Mild Impairment for Each PSP Rating Scale Domain Subscore as PSP Rating Scale Total Score Worsens – PSP (all 4 studies) vs CBS (4RTNI) (upper panel), and as CGIds and SEADL Worsen – AL-108–231, 4RTNI, and TAUROS Studies Combined (lower panel).

Abbreviation: CBS, corticobasal syndrome; CGIds, Clinical Global Impression of Disease Severity; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; SEADL, Schwaab and England Activities of Daily Living. Dashed line represents the average score of a patient entering a clinical trial (Table 2); PSPRS=38, SEADL=55, CGIds=4 for PSP patients and 28 for CBS patients.

Note: Link to online version with 95% Cis: https://pspmodel.shinyapps.io/PSP_Progression/

As expected, on average a patient with mild CBS (total score <25) presented with higher limb-motor impairment than a mild PSP patient, and showed little to no ocular impairment (Figure 2, upper panels). Less than 50% of patients with severe CBS suffered bulbar impairment – meaning it was less prevalent on average than in severe PSP patients. The probability of decline within the Gait and History domains was similar among patients with CBS and PSP.

Symptom domains begin to deteriorate in roughly the same order, regardless of whether they are measured by the PSPRS, CGIds, or SEADL (Figure 2, left panels and lower right panel). However, the CGIds and SEADL scale show smaller changes in probability that the History, Gait and Ocular domains will decline as the disease progresses, compared with the PSPRS. Hence it is difficult to distinguish which of these subscales will be most likely to deteriorate first when measured with CGIds or SEADL. The PSPRS shows a more distinct differentiation in the probability of decline of symptoms, and a fuller representation of the spectrum of disease, suggesting that the PSPRS better articulates the range of PSP patients than the more generalized scales.

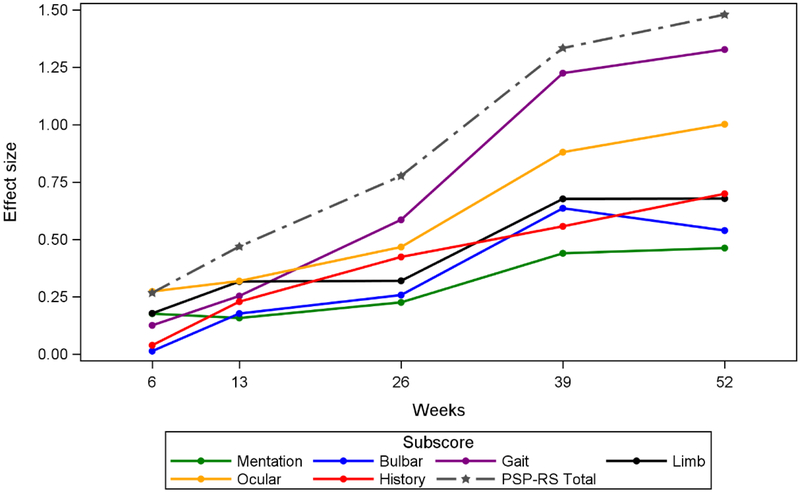

To confirm that the predicted sequence of PSPRS subscale changes is reflected by the actual longitudinal data collected in these studies, we plotted the mean subscale changes over 1 year in PSP across all 4 studies (Figure 3). This MMRM longitudinal analysis showing effect sizes over time for PSP patients supports the cross-sectional POM analysis (Figure 2). In this analysis, Ocular shows the highest signal early on but the strongest acceleration within a short period of time (12 months) is in Gait. The history domain in the 12-month longitudinal model appears to have less importance than observed in the POM where it had the same gradient as gait impairment.

Figure 3. Longitudinal Model of Change from Baseline PSP Rating Scale Subscores and Total Score of Placebo PSP-Richardson’s Syndrome Patients (AL-108–231 and 4RTNI).

Note: Link to online version with 95% Cis: https://pspmodel.shinyapps.io/PSP_Progression/

Discussion

Here we present a novel, interactive, online tool to model disease progression in PSP-Richardson’s Syndrome and CBS. The interactive scale provided in the online appendix demonstrates the linear probability of domain impairment across disease severity in both PSP and CBS indexed by PSPRS. On the interactive scale (Appendix 1), advancing the slider by 11 points on the total rating score [5–7] gives a prediction of how that PSP patient may deteriorate over the following 12 months. Although gender and age are not significant covariates (i.e. male and female deterioration is roughly similar) individuals are still able to enter their own demographic characteristics, and therefore more accurately represent how an individual’s disease may progress as well as enabling a more bespoke experience for the end user. This study also shows that the PSPRS can analytically capture decline in CBS. The pattern of domain impairment observed in the PSPRS is distinct from PSP and consistent, with the expected early limb impairment reflecting the apraxia and dystonia quantified in the current research criteria [17,22].

We used cross-sectional PSP Rating Scale data to model the contribution of symptom domains to overall severity in a broad 4R tauopathy population, encompassing 4 independent, multicentre cohorts of PSP patients and one multicentre CBS cohort. The results demonstrate a consistent order of probable progression of different symptoms, which varies depending on baseline diagnosis (CBS or PSP Richardson’s) and the severity of the patient, but was reproducible between the different studies.

Presenting features of PSP are typically behavioural changes, falls, ocular motor abnormalities, and Parkinsonism. With progression, there is gait impairment, dysarthria, dysphagia, emotional lability, and variable cognitive impairment. Terminally, there may be opthalmoplegia, rigid paralysis, dysphagia, and anarthria.

The PSPRS has been validated [11] in a non-interventional setting and has subsequently been the scale of choice when evaluating PSP patients in clinical trials [7–9,6, 18–20]. Prior studies of progression of disease demonstrate a consistent rate of progression by PPSPRS ranging from 9.9–13.7 points per year [7–9]. Median onset of severe functional impairments in motor, speech, and gait occur between 48 and 71 months after the initial onset of symptoms [21].

The results of this paper provide a quantitative approach to describe the pattern of domain impairment that are consistent with the clinical-pathological features of PSP-Richardson’s, as defined by recent consensus criteria [22]. In mild disease, ocular motor and gait are the predominant domains affected, increasing and including history and limb at moderate stages, and all domains at late stages. The order of disease symptoms contributing to progression for PSP is the same, regardless of whether the SEADL, CGIds, or PSPRS were used as the metric of disease severity providing additional validation of the relevance of the PSPRS in capturing clinically meaningful progression. Since PSPRS is a disease-specific scale, the pattern of domain decline is more precise than the generic scales.

The variability for PSP effect size modelling is minimal, suggesting a good fit and reasonable predictability. However, the confidence intervals (CIs) of the curves overlap for some subscores showing there is variability for an individual patient’s probable path of progression and hence this tool is best used for understanding the behaviour of PSP in large groups such as clinical trial populations. Interestingly, the variability of the probability estimates varies by subscore and by severity of overall disease. The variability of the mean is driven by the size of the population at a given score. Ocular subscale shows wide variability in the very early stages of disease but narrows as disease progresses as most patients have impairments. Gait and History have wider variability than Limb and Mentation for mildly impaired patients, but all show similar variability for severe impairment. Bulbar has low variability for mild impairment but wide variability for severe impairment; this is as expected as very few patients with severe Bulbar impairment were observed in this study. Moreover, this parallels experience from natural history studies of PSP that demonstrate variability of bulbar deficits in PSP [21].

Strength and Potential Limitations of Analyses

Using a combination of both cross-sectional and longitudinal modelling is a strength of this study. The longitudinal modelling shows the observed modelled progression as well as full scale of severity; it does not attempt to relate the total score to the subdomains. The cross-sectional modelling allows a direct assessment of the subdomains from the patient’s total score modelled over the full disease spectrum (i.e. longer than observed 12 months).

Potential limitations are: limited data at extremes of disease spectrums and hence caution in interpreting potential extrapolation is required; cut-offs of none/mild, moderate, severe are somewhat arbitrary and only based on an appropriate posthoc fit to the distribution of the observed data; given enrolment criteria some subtypes are not well represented, for example, the Parkinson predominant subtype, and early changes may be biased by those features that are most predictive of diagnosis and those physically able to participate in a clinical trial; and corticobasal syndrome subset is small compared to PSP data. Furthermore, symptom domains are likely to be clinicopathologically dependent, in this study they are treated independently; for instance, a limb motor deficit would likely affect gait. A future analysis could explore these correlations. A future addition to the online tool would be to add further subtypes of PSP as well as increase the number of CBS patients.

Conclusions

This paper evaluates a large compilation of PSP Rating Scale data from completed or ongoing clinical studies to understand better the contribution of symptom domains across the range of disease severity in PSP, with a smaller data set of CBS for comparison. Modelling and understanding how specific components of disease progress in relation to each other may facilitate detection of therapeutic effects at each stage of PSP and CBS in future clinical trials and may inform clinical trial design with more clinically meaningful outcomes. Moreover, these data support the feasibility of combined 4RT clinical trials, potentially enrolling both CBS and PSP-RS patients. Consistency of probable disease progression between generic scales (SEADL and CGIds) and the disease-specific PSPRS helped validate the findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jeremie Lebrec for his continued analytical support and guidance on this project, Carsten Henneges for his initial work to enable this modelling, and Alex Brittain for his medical writing/editing expertise.

Funding: The AL-108–231, TAUROS and PROSPERA clinical trials were conducted and funded by the respective companies. 4RTNI is funded by the NIH (R01AG038791; U54NS092089); Eli Lilly funded the analyses for this paper.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: KB, CB, MI, and AM were employees of, and stockholders in, Eli Lilly and Company at the time of writing. Eli Lilly contracted with inVentiv Health Clinical for editorial support of this document.

Financial Disclosures KB, CB, MI, and AM are employees of, and stockholders in, Eli Lilly and Company.

DM receives income through UC San Francisco and has no other financial parties to disclose.

ALB receives research support from the NIH (R01AG038791, U54NS092089), the University of California, the Tau Consortium, CBD Solutions, the Bluefield Project to Cure FTD, the Alzheimer’s Association and the following companies: Avid, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, C2N Diagnostics, Cortice Biosciences, Eli Lilly, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Roche and TauRx; has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Asceneuron, Celgene, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Samumed, Toyama and UCB; serves on a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for Neurogenetics Pharmaceuticals; has stock and/or options in Aeton, Alector and Delos.

TDS has not received research grants, has not served as a consultant and has not participated in any Advisory Board during the last year. He has no Intellectual Property Rights, Royalties, Contracts or Grants. He has stock in Pharmamar.

SL has received research grants from the Bavarian State and the Deutsche Stifterverband. He has received honoraria for presentations from UCB and Abbvie. He has not served as a consultant and has not participated in any Advisory Board during the last year. He has no Intellectual Property Rights, Royalties, Contracts stock ownerships.

GH has served on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Alzprotect, Asceneuron, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche, Sellas Life Sciences Group, UCB; has received honoraria for scientific presentations from Abbvie, Roche, Teva, UCB, has received research support from CurePSP, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), German Parkinson’s Disease Foundation (DPG), German PSP Association (PSP Gesellschaft), German Research Foundation (DFG) and the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), International Parkinson’s Fonds (IPF), the Sellas Life Sciences Group; has received institutional support from the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE).

GH was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, HO2402/6–2 & Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology SyNergy).

References

- 1.Coyle-Gilchrist I, Dick K, Patterson K et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology. 2016; May 3; 86(18): 1736–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golbe LI, Davis PH, Schoenberg BS, Duvoisin RC. Prevalence and natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 1988; 38:1031–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kouri N, Ross OA, Dombroski B, et al. Genome-wide association study of corticobasal degeneration identifies risk variants shared with progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat Commun 2015: 16: 7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai RM and Boxer AL. Clinical Trials: past, current and future for atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Semin Neurol 2014; 34: 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamelou M, Höglinger G. A Review of Treatment Options for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. CNS Drugs 2016; 30: 629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolosa E, Litvan I, Höglinger GU, et al. A phase 2 trial of the GSK-3 inhibitor tideglusib in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2014; 29: 470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boxer AL, Lang AE, Grossman M, et al. Davunetide in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 676–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuebling G, Hensler M, Paul S, Zwergal A, Crispin A, Lorenzl S. PROSPERA: a randomized, controlled trial evaluating rasagiline in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol 2016; 263: 1565–7154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boxer AL, Yu J-T, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Lang AE, Höglinger GU. Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: New diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(7):552–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology 2013; 80: 496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golbe L, Ohman-Strickland PA. A clinical rating scale for progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 2007; 130: 1552–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agresti A Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd Edition, Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henneges C, Reed C, Chen YE, Dell’Agnello G, Lebrec J. Describing the Sequence of Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Results from an Observational Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 52: 1065–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yee TW, Wild CJ. Vector Generalized Additive Models. Journal of Royal Statistical Society B 1996; 58: 481–493. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yee TW. Vector Generalized Linear and Additive Models: With an Implementation in R, New York, Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang W, Cheng J, Allaire JJ, Xie Y and McPherson J, “shiny: Web Application Framework for R. R package version 1.0.0.”, 2017

- 17.Litvan I, Campbell G, Mangone CA, et al. Which clinical features differentiate progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) from related disorders?. A clinicopathological study. Brain 1997; 120: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamelou M, Reuss A, Pilatus U, et al. Short-term effects of coenzyme Q10 in progressive supranuclear palsy: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mov Disord 2008; 23: 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apetauerova D, Scala SA, Hamill RW, et al. CoQ10 in progressive supranuclear palsy: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016; 3: e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leclair-Visonneau L, Rouaud T, Debilly B, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of sodium valproate in progressive supranuclear palsy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2016; 146: 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetz CG, Leurgans S, Lang AE, Litvan I. Progression of gait, speech and swallowing deficits in progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology 2003; 60: 917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, Mollenhauer B, Müller U, Nilsson C, Whitwell JL, Arzberger T, Englund E, Gelpi E, Giese A, Irwin DJ, Meissner WG, Pantelyat A, Rajput A, van Swieten JC, Troakes C, Antonini A, Bhatia KP, Bordelon Y, Compta Y, Corvol JC, Colosimo C, Dickson DW, Dodel R, Ferguson L, Grossman M, Kassubek J, Krismer F, Levin J, Lorenzl S, Morris HR, Nestor P, Oertel WH, Poewe W, Rabinovici G, Rowe JB, Schellenberg GD, Seppi K, van Eimeren T, Wenning GK, Boxer AL, Golbe LI, Litvan I; Movement Disorder Society-endorsed PSP Study Group. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord. 2017. June;32(6):853–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.