Abstract

Ion channels play a key role in our body to regulate homeostasis and conduct electrical signals. With the help of advances in structural biology, as well as the discovery of numerous channel modulators derived from animal toxins, we are moving toward a better understanding of the function and mode of action of ion channels. Their ubiquitous tissue distribution and the physiological relevancies of their opening and closing suggest that cation channels are particularly attractive drug targets, and years of research has revealed a variety of natural toxins that bind to these channels and alter their function. In this review, we provide an introductory overview of the major cation ion channels: potassium channels, sodium channels and calcium channels, describe their venom-derived peptide modulators, and how these peptides provide great research and therapeutic value to both basic and translational medical research.

Keywords: ion channel, venom, toxin peptides, animal toxin, ion channel pharmacology

Introduction

Cone snails whose shells are coveted for their elaborate patterns, yellow dart frogs measuring just a few centimeters long, and transparent bell-shaped jellyfish with delicate tentacles might all seem unlikely candidates, but they are among the deadliest animals in the world. Like the more obvious perilous creatures – venomous snakes, spiders and scorpions – these animals release toxins that dramatically modulate the activity of various targets including ion channels, thereby affecting cellular communication and disrupting normal biochemical and physiological processes in prey or predator.

Animal venom is a complex mixture of various components – inorganic salts, organic molecules like alkaloids, proteins and peptides (King, 2011). While this concoction enables a multi-pronged attack upon the target organism, it has also led to an entire collection of bio-active compounds being available to researchers for probing the structural and functional properties of their molecular targets. Since ion channels play an essential role in neuronal signaling and muscle contractions, it is unsurprising that many venom toxins have evolved to block or modulate the function of ion channels (Dutertre and Lewis, 2010). Not only have venom-derived peptides been used extensively in probing ion channels, the understanding of the mechanism of this interaction has also led to the development of venom-based therapeutics targeting various ion channels. In fact, the recognition of animal venom having medicinal benefits is not a recent phenomenon. Venom from various animals had been used as medicines for centuries, in civilizations all over the world (Bhattacharjee and Bhattacharyya, 2014; Utkin, 2015).

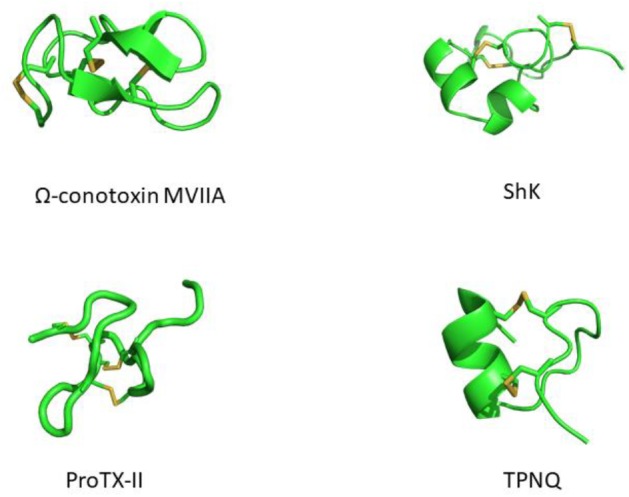

Modern medicine has shown conclusively that venoms contain compounds with therapeutic potential. Many of these have been isolated, analyzed for structure and function, and have served as scaffolds for the development of various drugs. Venom peptides have evolved to be highly stable, being able to withstand degradation by proteolytic enzymes in the foreign environment they are injected into and in the venom itself. This stability is conferred by one or more disulfide bridges (Figure 1). While the peptides mutate into more potent and/or selective variants, the structurally important cysteines tend to be highly conserved. Cystine-stabilized α/β fold, inhibitor cystine knot (ICK, or knottin) and the three-finger toxin motif are all highly prevalent motifs in these peptides (Undheim et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1.

Structures of venom-derived peptide toxins – clockwise from top-left: ω-conotoxin MVIIA (PDB: 1MVI), ShK (PDB: 1ROO), TPNQ (PDB: 1TER), and ProTX-II (PDB: 2N9T). Disulfide linkages are shown in yellow.

This mini-review briefly describes exemplar peptides derived from animal venom, which have been used to probe the structure and function of voltage-activated cation channels, as well as are being developed as potential therapeutics (listed in Table 1). Here, we describe ion channels that are selectively permeable to potassium, calcium, and sodium ions.

Table 1.

Venom-derived peptide modulators of cation channels.

| Channel | Toxin | Species | IC50/Kd | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kir1.1 | Lq2 (α-KTx1.2) | Leiurus quinquestriatus | 410 nM | Lu and MacKinnon, 1997 |

| δ-DTX | Dendroaspis angusticeps | 150 nM | Imredy et al., 1998 | |

| Tertiapin (TPN) | Apis mellifera | 2 nM | Jin and Lu, 1998 | |

| Kir3.1/Kir3.4 | Tertiapin (TPN) | Apis mellifera | 8 nM | Jin and Lu, 1998 |

| Kv1.1 | α-DTx | Dendroaspis angusticeps | 20 nM | Grissmer et al., 1994 |

| DTx K (toxin I) | Dendroaspis polylepis | 50 nM | Robertson and Owen, 1993 | |

| α-KTx 2.2 (margatoxin) | Centruroides margaritatus | 4.2 nM | Bartok et al., 2014 | |

| α-KTx 2.5 (hongotoxin) | Centruroides limbatus | 31 pM | Koschak et al., 1998 | |

| α-KTx 3.13 | Mesobuthus eupeus | 203 pM | Gao et al., 2010 | |

| ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | 16 pM | Kalman et al., 1998 | |

| Kv1.2 | α-DTx | Dendroaspis angusticeps | 17 nM | Grissmer et al., 1994 |

| α-KTx 1.1 (Charybdotoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 9 nM | Takacs et al., 2009 | |

| α-KTx 10.1 (Cobatoxin-1) | Centruroides noxius | 27 nM | Jouirou et al., 2004 | |

| α-KTx 2.1 (Noxiustoxin) | Centruroides noxius | 2 nM | Grissmer et al., 1994 | |

| α-KTx 2.2 (margatoxin) | Centruroides margaritatus | 6 pM | Bartok et al., 2014 | |

| α-KTx 2.5 (hongotoxin) | Centruroides limbatus | 0.17 nM | Koschak et al., 1998 | |

| α-KTx 3.6 (mesomartoxin) | Mesobuthus martensii | 15 nM | Wang et al., 2015 | |

| α-KTx 6.4 | Pandinus imperator | 8 pM | Sarrah et al., 2003 | |

| α-KTx-6.2 (Maurotoxin) | Scorpio maurus palmatus | 0.8 nM | Ryadh et al., 2018 | |

| α-KTx-6.21 (Urotoxin) | Urodacus yaschenkoi | 160 pM | Luna-Ramírez et al., 2014 | |

| ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | 9 nM | Kalman et al., 1998 | |

| BscTx1 | Bunodosoma caissarum | 30 pM | Orts et al., 2013 | |

| Kv1.3 | α-KTx 6.12 (Anuroctoxin) | Anuroctonus phaiodactylus | 0.73 nM | Bagdáany et al., 2005 |

| α-KTx 3.12 (Aam-KTX) | Androctonus amoreuxi | 1.1 nM | Abbas et al., 2008 | |

| α-KTx 2.1 (Noxiustoxin) | Centruroides noxius | 1 nM | Grissmer et al., 1994 | |

| α-KTx 2.2 (margatoxin) | Centruroides margaritatus | 11 pM | Bartok et al., 2014 | |

| α-KTx 2.5 (hongotoxin) | Centruroides limbatus | 86 nM | Koschak et al., 1998 | |

| α-KTx 6.15 (Hemitoxin) | Hemiscorpius lepturus | 2 nM | Najet et al., 2008 | |

| α-KTx 6.3 (Neurotoxin) | Heterometrus spinifer | 12 pM | Lebrun et al., 1997 | |

| α-KTx 3.2 (Agitoxin-2) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 200 pM | Garcia et al., 1994 | |

| α-KTx 12.5 (LmKTx10) | Lychas mucronatus | 28 nM | Liu et al., 2009 | |

| α-KTx 3.11 | Odonthobuthus doriae | 7.2 nM | Abdel-Mottaleb et al., 2008 | |

| α-KTx3.7 | Orthochirus scrobiculosus | 14 pM | Mouhat et al., 2005 | |

| α-KTx 23.1 (Vm24) | Vaejovis mexicanus smithi | 2.9 pM | Varga et al., 2012 | |

| ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | 11 pM | Kalman et al., 1998 | |

| Kv1.6 | α-DTx | Dendroaspis angusticeps | 9 nM | Swanson et al., 1990 |

| α-KTx 1.1 (Charybdotoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 22 nM | Garcia et al., 1994 | |

| α-KTx 3.2 (Agitoxin-2) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 37 pM | Garcia et al., 1994 | |

| ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | 165 pM | Kalman et al., 1998 | |

| BcSTx1/BcSTx2 | Bunodosoma caissarum | 1.3 nM/7.7 nM | Orts et al., 2013 | |

| Kv2.1 | HaTx1 (Hanatoxin) | Grammostola spatulata | 42 nM | Swartz and MacKinnon, 1995 |

| JZTX-III/JZTX-XI | Chilobrachys jingzhao | 710 nM/390 nM | Tao et al., 2013, 2016 | |

| ScTx1 | Stromatopelma calceata | 12.7 nM | Escoubas et al., 2002 | |

| Kv2.2 | ScTx1 | Stromatopelma calceata | 21.4 nM | Escoubas et al., 2002 |

| Kv3.2 | ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | 6 nM | Yan et al., 2005 |

| Kv3.4 | BDS-I/BDS-II | Anemonia sulcata | 47 nM/56 nM | Diochot et al., 1998 |

| Kv4.1 | JZTX-XII | Chilobrachys jingzhao | 363 nM | Yuan et al., 2007 |

| Kv4.2 | PaTx1/PaTx2 | Phrixotrichus auratus | 5 nM/34 nM | Diochot et al., 1999 |

| ScTx1 | Stromatopelma calceata | 1.2 nM | Escoubas et al., 2002 | |

| TsTx-Kβ (Ts8) | Tityus serrulatus | 652 nM | Pucca et al., 2016 | |

| HpTx3 (Heteropodatoxin) | Heteropoda venatoria | 67 nM | Sanguinetti et al., 1997 | |

| JZTX-V | Chilobrachys jingzhao | 604.2 nM | Zeng et al., 2007 | |

| Kv4.3 | PaTx1/PaTx2 | Phrixotrichus auratus | 28 nM/71 nM | Diochot et al., 1999 |

| SNX-482 | Hysterocrates gigas | 3 nM | Kimm and Bean, 2014 | |

| KCa1.1 | α-KTx1.1 (Charybdotoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus | 2.9 nM | Rauer et al., 2000 |

| α-KTx 1.3 (Iberiotoxin) | Mesobuthus tamulus | 1.7 nM | Candia et al., 1992 | |

| α-KTx 1.5 (BmTx1) | Buthus martensi Karsch | 0.6 nM | Romi-Lebrun et al., 1997 | |

| α-KTx 1.6 (BmTx2) | Buthus martensi Karsch | 0.3 nM | Romi-Lebrun et al., 1997 | |

| α-KTx 1.11 (Slotoxin) | Centruroides noxius | 1.5 nM | Garcia-Valdes et al., 2001 | |

| α-KTx 3.1 (Kaliotoxin) | Androctonus mauretanicus | 20 nM | Crest et al., 1992 | |

| α-KTx 3.5 (Kaliotoxin2) | Androctonus australis | 135 nM | Crest et al., 1992 | |

| α-KTx 12.1 (Butantoxin) / TsTX-IV | Tityus serrulatus | 50 nM | Novello et al., 1999 | |

| α-KTx (BmP09) | Buthus martensi Karsch | 27 nM | Yao et al., 2005 | |

| Natrin | Naja naja atra | 34.4 nM | Wang et al., 2005 | |

| KCa2.1 | α-KTx 5.1 (Leiurotoxin I/scyllatoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 325 nM | Castle and Strong, 1986 |

| Tamapin | Mesobuthus tamulus | 32 nM | Pedarzani et al., 2002 | |

| Apamin | Apis mellifera | 8 nM | Hugues et al., 1982 | |

| KCa2.2 | α-KTx 5.1 (Leiurotoxin I/scyllatoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 200 pM | Castle and Strong, 1986 |

| PO5 | Androctonus mauretanicus | 22 nM | Zerrouk et al., 1993 | |

| Tamapin | Mesobuthus tamulus | 24 pM | Pedarzani et al., 2002 | |

| Apamin | Apis mellifera | 30-200 pM | Hugues et al., 1982 | |

| TsK | Tityus serrulatus | 80 nM | Lecomte et al., 1999 | |

| KCa2.3 | α-KTx 5.1 (Leiurotoxin I/scyllatoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 1.1 nM | Castle and Strong, 1986 |

| PO5 | Androctonus mauretanicus | 25 nM | Zerrouk et al., 1993 | |

| Tamapin | Mesobuthus tamulus | 1.7 nM | Pedarzani et al., 2002 | |

| Apamin | Apis mellifera | 10 nM | Hugues et al., 1982 | |

| TsK | Tityus serrulatus | 197 nM | Lecomte et al., 1999 | |

| KCa3.1 | α-KTx 1.1 (Charybdotoxin) | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 5 nM | Ghanshani et al., 2000; Rauer et al., 2000 |

| α-KTx 6.2 (Maurotoxin) | Maurus palmatus | 1 nM | Castle, 2003 | |

| Margatoxin | Centruroides margaritatus | 459 nM | Garcia-Calvo et al., 1993 | |

| α-KTx 3.7 (OSK1) | Orthochirus scrobiculosus | 225 nM | Mouhat et al., 2005 | |

| ShK | Stichodactyla helianthus | 30 nM | Pennington et al., 1995 | |

| BgK | Bunodosoma granulifera | 172 nM | Cotton et al., 1997 | |

| Nav1.1 | MeuNaTxα-12 | Mesobuthus eupeus | 0.91 μM | Zhu et al., 2012 |

| MeuNaTxα-13 | Mesobuthus eupeus | 2.5 μM | Zhu et al., 2012 | |

| ATX-II | Anemonia sulcata | 6 nM | Chahine et al., 1996; Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Cangitoxin-II; CGTX-II | Bunodosoma cangicum | 0.165 μM | Zaharenko et al., 2012 | |

| Bc-III | Bunodosoma caissarum | 300 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| AFT-II | Anthopleura fuscoviridis | 391 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| GVIIJSSG | Conus geographus | 11 nM | Gajewiak et al., 2014 | |

| μ-Conotoxin BuIIIA | Conus bullatus | 0.35 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| Nav1.2 | Huwentoxin IV | Haplopelma schmidti | 150 nM | Minassian et al., 2013 |

| ATX-II | Anemonia sulcata | 41 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Bc-III | Bunodosoma caissarum | 1449 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| AFT-II | Anthopleura fuscoviridis | 1998 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Lqh-2 | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 1.8 nM | Chen et al., 2002 | |

| PnTx1 | Phoneutria nigriventer | 33.7 nM | Silva et al., 2012 | |

| Phrixotoxin 3 (PaurTx3) | Phrixotrichus auratus | 0.6 nM | Bosmans et al., 2006 | |

| ProTx-III | Thrixopelma pruriens | 0.3 μM | Cardoso et al., 2015 | |

| Hainantoxin-IV | Ornithoctonus hainana | 36 nM | Liu et al., 2003 | |

| GrTx1 | Grammostola rosea | 0.23 μM | Redaelli et al., 2010 | |

| GVIIJSSG | Conus geographus | 11 nM | Gajewiak et al., 2014 | |

| μ-conotoxin TIIIA | Conus tulipa | 0.045 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin SIIIA | Conus striatus | 0.05 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin KIIIA | Conus kinoshitai | 0.003 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin MIIIA | Conus magus | 0.45 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin BuIIIA | Conus bullatus | 0.012 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| Nav1.3 | AFT-II | Anthopleura fuscoviridis | 460 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 |

| ATX-II | Anemonia sulcata | 759 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Bc-III | Bunodosoma caissarum | 1458 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| ProTx-III | Thrixopelma pruriens | 0.9 μM | Cardoso et al., 2015 | |

| Hainantoxin-IV | Ornithoctonus hainana | 375 nM | Liu et al., 2003 | |

| GrTx1 | Grammostola rosea spider | 0.77 μM | Redaelli et al., 2010 | |

| GVIIJSSG | Conus geographus | 15 nM | Gajewiak et al., 2014 | |

| μ-conotoxin BuIIIA | Conus bullatus | 0.35 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| Nav1.4 | AFT-II | Anthopleura fuscoviridis | 31 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 |

| ATX-II | Anemonia sulcata | 109 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Bc-III | Bunodosoma caissarum | 821 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| MrVIB (μO-Conotoxin) | Conus marmoreus | 222 nM | Zorn et al., 2006 | |

| MfVIA (μO-Conotoxin) | Conus magnificus | 81 nM | Vetter et al., 2012 | |

| GrTx1 | Grammostola rosea | 1.3 μM | Redaelli et al., 2010 | |

| GVIIJSSG | Conus geographus | 47 nM | Gajewiak et al., 2014 | |

| μ-conotoxin TIIIA | Conus tulipa | 0.005 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin SIIIA | Conus striatus | 0.13 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin MIIIA | Conus magus | 0.33 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| μ-conotoxin BuIIIA | Conus bullatus | 0.012 μM | Wilson et al., 2011 | |

| Nav1.5 | ProTx-II | Thrixopelma pruriens | 79 nM | Middleton et al., 2002 |

| ATX-II | Anemonia sulcata | 49 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| AFT-II | Anthopleura fuscoviridis | 62.5 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Bc-III | Bunodosoma caissarum | 307 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| CGTX-II | Bunodosoma cangicum | 50 nM | Zaharenko et al., 2012 | |

| Nav1.6 | ATX-II | Anemonia sulcata | 180 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 |

| AFT-II | Anthopleura fuscoviridis | 300 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| Bc-III | Bunodosoma caissarum | 900 nM | Oliveira et al., 2004 | |

| ProTx-II | Thrixopelma pruriens | 47 nM | Maertens et al., 2006 | |

| CGTX-II | Bunodosoma cangicum | 50 nM | Zaharenko et al., 2012 | |

| ProTx-III | Thrixopelma pruriens | 0.29 μM | Cardoso et al., 2015 | |

| GrTx1 | Grammostola rosea spider | 0.63 μM | Redaelli et al., 2010 | |

| Nav1.7 | ProTx-I | Thrixopelma pruriens | 51 nM | Middleton et al., 2002 |

| ProTx-II | Thrixopelma pruriens | 300 pM | Schmalhofer et al., 2008 | |

| ProTx-III | Thrixopelma pruriens | 2.1 nM | Cardoso et al., 2015 | |

| Lqh-2 | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 32 nM | Chen et al., 2002 | |

| Lqh-3 | Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus | 13.6 nM | Chen et al., 2002 | |

| GpTx-1 | Grammostola porteri | 10 nM | Murray et al., 2015 | |

| μ-SLPTX-Ssm6a | Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans | 25 nM | Yang et al., 2013 | |

| Hainantoxin-IV | Ornithoctonus hainana | 21 nM | Liu et al., 2003 | |

| μ-TRTx-Pn3a | Pamphobeteus nigricolor | 0.9 nM | Deuis et al., 2017 | |

| GrTx1 | Grammostola rosea | 0.37 μM | Redaelli et al., 2010 | |

| GVIIJSSG | Conus geographus | 41 nM | Gajewiak et al., 2014 | |

| Huwentoxin-IV | Haplopelma schmidti | 26 nM; 0.4 nM | Xiao et al., 2008; Rahnama et al., 2017 | |

| Nav1.8 | ProTx-I | Thrixopelma pruriens | 27 nM | Middleton et al., 2002 |

| MrVIB (μO-Conotoxin) | Conus marmoreus | 102 nM | Ekberg et al., 2006 | |

| MfVIA (μO-Conotoxin) | Conus magnificus | 529 nM | Vetter et al., 2012 | |

| HSTX-I | Haemadipsa sylvestris | 2.44 μM | Wang et al., 2018 | |

| Nav1.9 | HSTX-I | Haemadipsa sylvestris | 3.30 μM | Wang et al., 2018 |

| Cav1.2 | Calciseptine | Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis | 430 nM | de Weille et al., 1991 |

| Cav2.1 | ω-conotoxin CVIB | Conus catus | 7.7 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 |

| ω-conotoxin CVIC | Conus catus | 7.6 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-conotoxin MVIIC | Conus magus | 7 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-agatoxin IVA | Agelenopsis aperta | 0.1 μM | Mintz et al., 1992 | |

| ω-grammotoxin SIA | Grammostola rosea | 50 nM | Lampe et al., 1993; McDonough et al., 1997 | |

| Cav2.2 | ω-agatoxin IIA | Agelenopsis aperta | 10 nM | Bindokas and Adams, 1989; Adams et al., 1990 |

| ω-agatoxin IIIA | Agelenopsis aperta | 1.4 nM | Ertel et al., 1994; Olivera et al., 1994 | |

| ω-agatoxin IIIB | Agelenopsis aperta | 140 nM | Ertel et al., 1994; Yan and Adams, 2000 | |

| ω-agatoxin IIID | Agelenopsis aperta | 35 nM | Ertel et al., 1994 | |

| ω-ctenitoxin-Pn3a/Neurotoxin Tx3–4 | Phoneutria nigriventer | 50 pM | Cordeiro Mdo et al., 1993 | |

| ω-conotoxin CVIA | Conus catus | 0.6 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-conotoxin CVIB | Conus catus | 7.7 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-conotoxin CVIC | Conus catus | 7.6 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-conotoxin CVID | Conus catus | 0.07 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-conotoxin MVIIA | Conus magus | 0.055 nM | Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| ω-conotoxin GVIA | Conus geographus | 0.04 nM | Olivera et al., 1984; Lewis et al., 2000 | |

| Cav2.3 | SNX482 | Hysterocrates gigas | 15–30 nM | Newcomb et al., 1998 |

| Cav3.1 | Kurtoxin | Parabuthus transvaalicus | 15–50 nM | Chuang et al., 1998; Sidach and Mintz, 2002 |

| ProTx1 | Thrixopelma pruriens | 200 nM | Ohkubo et al., 2010 | |

| Cav3.2 | Kurtoxin | Parabuthus transvaalicus | 25–50 nM | Chuang et al., 1998; Sidach and Mintz, 2002 |

Venom Peptides Targeting Potassium Channels

Potassium ion channels are of high therapeutic value due to their broad and active presence in a variety of human tissue. To date, numerous disease conditions in neuronal, cardiac, immune, and endocrine systems have been reported to be directly associated with malfunction of potassium channels. Potassium channels are categorized into four families: two transmembrane (TM) Kir channels, four TM, two pore-domain K2P channels, and six TM Kv and KCa channels (Chuan et al., 2013). Here, we discuss the Kir, Kv and KCa channels. The K2P family of channels contribute to voltage-independent “leak” K+ current, and are structurally different from other classes of K+ channels in that they assemble as ‘dimer of dimers’ (Goldstein et al., 2005). No venom-derived peptide toxins have been reported for K2P channels yet (McQueen, 2017).

Inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channels were first described in 1949 in frog skeletal muscles (Katz, 1949), however, they were not cloned and isolated until 1993 (Ho et al., 1993; Kubo et al., 1993). As the name suggests, Kir channels inwardly rectify outward K+ current, allowing extracellular K+ to readily flow into the cells. The unique molecular mechanism is due to the intracellular binding of Mg2+ and polyamines (Lu, 2004). Kir channels are homo- or hetero- tetrameric structures assembled from four Kir subunits, containing two TM segments separated by a selectivity filter region (Whorton and MacKinnon, 2011; Li et al., 2017). Structural, functional and pathophysiological details of four specific types of Kir channels have been detailed elsewhere (Hibino et al., 2010).

The peptides that show high affinity toward Kir channels (IC50 < 0.5 μM) are scorpion toxin ChTx2 (α-KTx1.2), snake toxin δ-dendrotoxin (δ-DTX), and honey bee toxin Tertiapin (TPN) (Lu and MacKinnon, 1997; Imredy et al., 1998; Jin and Lu, 1998; Doupnik, 2017). Like many other venom toxins, these three molecules are rich in cysteine and positively charged residues. Computational simulation and docking studies have hypothesized binding mechanisms of these toxins (Li et al., 2016). Positively charged residues from toxin come into close contact with negatively charged residues on channel pore region, strengthening electrostatic interactions between the two. Hydrophobic forces between aliphatic residues also count into binding affinity.

TPN and TPNM13Q are considered the most potent inhibitors. TPN binds to Kir1.1 and Kir3.1/3.4 at 2-8 nM (EC50), thus being an ideal tool for investigations of Kir channels’ functional and pharmacological properties (Dobrev et al., 2005; Walsh, 2011). TPN has shown potential therapeutic use in a canine model, treating atrial fibrillation, without causing ventricle arrhythmia (Hashimoto et al., 2006). More recently, TPN, together with sodium channel blockers, has been shown to have synergistic effects in preventing atrial fibrillation and prolonging atrial effective refractory period. The combination formula has been patented for medication manufacturing by Gilead Sciences.

Voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels tightly control membrane permeability of K+ by sensing voltage change, thereby playing a key role in regulating action potential and propagating electrical signals in excitable cells (Yellen, 2002). In non-excitable cells, Kv channels modulate cellular metabolism and facilitate downstream signaling cascade; for example, Kv1.3 in T lymphocytes (Cahalan and Chandy, 2009). 40 Kv channels in 12 subfamilies have been found and many extensively studied (Alexander et al., 2017). Kv channels are homo- or hetero- tetramers, made up of four subunits each consisting of six TM helices. Voltage sensing domain (VSD) (S1–S4) is connected to pore domain (S5–S6) through S4–S5 intracellular loop, driving the pore to open or close (Long et al., 2005).

Research on venom peptide modulators of Kv channels started in 1980s, and to date more than 200 peptides with inhibitory effect on Kv channels have been identified (Carbone et al., 1982; Kuzmenkov et al., 2016). These polypeptides usually bind to Kv channels in two unique mechanisms. The pore blockers sit in the shallow vestibule at extracellular pore region, while the gating modifiers bind to the so-called “paddle motif” of the VSD accessible from the extracellular side.

Scorpion toxin charybdotoxin (ChTx) was one of the earliest venom toxins used as an important research tool to understand Kv channel subunit stoichiometry (MacKinnon, 1991), auxiliary beta subunits (Garcia et al., 1995), as well as its overall architecture (Hidalgo and MacKinnon, 1995).

Sea anemone toxin ShK blocks Kv channels at nanomolar to sub-nanomolar potency (Castañeda et al., 1995; Kalman et al., 1998). ShK and its analogs are blockers of the Kv channel pore. They bind to all four subunits in the channel tetramer by two key interactions within the external vestibule – Lys22 occludes the channel pore like a “cork in a bottle,” and Tyr23, together with Lys22, forms a “functional dyad” required for channel block. Many K+ channel-blocking peptides exhibit similar blocking mechanism, consisting of a dyad of lysine and neighboring aromatic/aliphatic residue (Chang et al., 2018). With the goal of developing a highly selective Kv1.3 inhibitor, nearly 10 years of effort was made to re-engineer the native ShK. In 2006, a stable analog, ShK-186 demonstrated specific binding to Kv1.3 at 69 pM, which is 100-fold selective to other Kv channels (Chi et al., 2012). ShK-186 (Dalazatide), now being developed by Kineta, has passed phase I clinical trials It is the only venom-derived peptide blocking K+ channels that is being developed as a therapeutic (Tarcha et al., 2012, Tarcha et al., 2017).

The hERG channel (or Kv11.1) plays a crucial role in the cardiac action potential by repolarizing IKr current, the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current. While selective Kv11.1-blockers are available (e.g., BeKm-1 from scorpion Mesobuthus eupeus) (Korolkova et al., 2001), it warrants special attention as many drugs/peptides intended for other targets, can exhibit non-selective binding to it, with potentially fatal consequences. Inhibition of hERG by drugs can lead to lengthening of the electrocardiographic QT interval, while hERG channel activators can cause drug-induced short QT syndrome. Both cases can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias. Hence, FDA guidelines recommend that all drugs that are intended for human use be evaluated for anti-hERG activity (Vandenberg et al., 2012).

Calcium (Ca2+)-activated potassium channels (KCa) are broadly divided into three subtypes based on their single channel conductance - big conductance (BKCa), intermediate conductance (IKCa) and small conductance (SKCa). While the BKCa channels are activated by both voltage and increase in cytosolic Ca2+, the IKCa and SKCa channels are activated exclusively by the latter. Like Kir and Kv channels, the KCa channels are tetramers made up of four α subunits. BKCa requires additional regulatory subunits, and is made up of 6/7 TM segments, while SKCa and IKCa contain 6 TM segments, with a calmodulin molecule bound to each subunit, serving as the Ca2+ sensor. One of the first peptide toxins that were found to inhibit K+ channels included apamin (derived from bee venom) and charybdotoxin (ChTX, derived from the scorpion venom) (Hugues et al., 1982; Rauer et al., 2000). Apamin blocks SK channels (KCa2), and served as a primary pharmacological tool to distinguish between KCa2 channels and KCa1.1/KCa3.1. ChTX inhibits both KCa channels (KCa1.1 and KCa3.1) and Kv channels (Kv1.2, Kv1.3, and Kv1.6). Another scorpion toxin iberiotoxin is selective for BK channel (KCa1.1) (Candia et al., 1992).

Venom Peptides Targeting Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels

Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels are present in the membranes of most excitable cells and are responsible for initiation and propagation of action potentials. Studies elucidating details of ion selectivity, hypothesizing the Nav pore diameter and binding mechanism of sodium-channel acting local anesthetics and related drugs, were bolstered by the availability of ion channel toxins, like the alkaloids tetrodotoxin (TTX) and saxitoxin (STX) (Hille, 1971, 1975, 1977; Armstrong et al., 1973). Studies to isolate and purify the Nav channel protein were pioneered by William Catterall and co-workers using, besides TTX and STX, scorpion toxin (ScTx) neuropeptides (Agnew et al., 1978; Beneski and Catterall, 1980; Hartshorne and Catterall, 1981).

Nav channels are divided into nine subtypes (Nav1.1–Nav1.9) based on their sequence, TTX binding and tissue expression. The 250 kDa channel-forming α-subunits are pseudo-tetrameric, wherein a single polypeptide chain folds into four homologous, non-identical domains (DI–IV), each containing six TM segments (S1–S6). The S5–S6 segments from all four domains form the central ion pore, while the S1–S4 segments in each domain form the VSD. A single channel is composed of one pore-forming α subunit, which may be associated with either one or two β subunits. The α subunit is functional on its own, and forms the core of the channel.

The venom of various animals contain toxins that target Nav channels to attack the neuromuscular systems of their adversaries and prey. Toxins that modulate Nav channel function generally do so in two ways – either by blocking the flow of Na+ ions through the pore, or by modifying the gating mechanisms.

One of the best studied pore blockers for Nav channels are the μ-conotoxin peptides from cone snails. Conotoxins are disulfide-rich peptides that are isolated from the venom of cone snails (genus Conus). Venom derived from cone snails is a treasure trove of peptide toxins for different ion channels and other receptor proteins (Olivera et al., 1985, 1990). M-conotoxins demonstrate the best binding with the skeletal muscle isoform of Nav channel, Nav1.4, with variable binding to other isoforms. These variations in targeting selectivity and affinity of each peptide for the different Nav isoforms constitute an important tool for distinguishing between different isoforms (Zhang et al., 2013). On the other hand are toxin peptides that modify Nav channel gating by interacting with the voltage sensors. Various classes of conotoxins interact with the voltage sensors of Nav channels and influence their gating properties. Δ-conotoxins are ubiquitously expressed in a range of cone snail venoms and inhibit fast inactivation of channels. While the μ-conotoxins are pore-blocking peptides, the μO-conotoxins are gating modifiers that target the voltage sensors and inhibit channel opening (Daly et al., 2004; Zorn et al., 2006; Leipold et al., 2007). MO-conotoxins were evaluated for their pain-relieving activity and found to be anti-nociceptive in animal models of pain (Teichert et al., 2012).

Several spider toxins are in pre-clinical development stage as antagonists of Nav1.7, an attractive target for development of non-opiod pain medication. Protoxin-II (ProTX-II), derived from the tarantula Thrixopelma pruriens, inhibits channel activation by shifting to positive potentials the voltage dependence of channel activation. Using ProTX-II as a scaffold, a highly potent and selective Nav1.7 blocking peptide (JNJ63955918) has been developed, the effect of which mirrors features of the Nav1.7-null phenotype (Flinspach et al., 2017). Another venom peptide, huwentoxin IV, is derived from the Chinese bird-eating spider Selenocosmia huwena (Peng et al., 2002). This peptide preferentially inhibits Nav1.7 by binding one of the four VSDs of the channel, making it more selective as compared to the local anesthetics that bind the conserved channel pore (Ragsdale et al., 1996; Xiao et al., 2008, 2011). Various mutational studies led to a triple mutant of huwentoxin IV (E1G, E4G, and Y33W) being developed with a very high potency toward Nav1.7 blocking (Revell et al., 2013).

Nav1.5 is expressed mainly in cardiac muscle, where it mediates fast depolarization phase of the cardiac action potential and is a target for class I anti-arrhythmic agents. Jingzhaotoxin-III (from the Chinese tarantula Chilobrachys jingzhao) selectively inhibits the activation of Nav1.5 in heart cells (IC50 ∼ 350 nM), but not Nav neuronal subtypes (Rong et al., 2011).

Sea anemones are another source of Nav-targeting peptides. Some key toxins are ATX-II (from Anemonia sulcata), AFT-II (from Anthopleura fuscoviridis) and Bc-III (from Bunodosoma caissarum). ATX-II strongly affects Nav1.1 and Nav1.2, while AFT-II affects Nav1.4 and Nav1.5. Given that these two differ in a single amino acid (ATX-II→K36A→AFTII), indicates that the lysine at position 36 is important for the very strong effects of ATX-II on Nav1.1/2 channels (Oliveira et al., 2004; Moran et al., 2009).

Venom Peptides Targeting Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels

Voltage-gated calcium channels (Cav) facilitate cellular calcium influx in response to membrane depolarization. They regulate hormone secretion, neurotransmitter release, propagation of cardiac action potential, muscle contraction and gene expression in different cell types (Catterall, 2011).

Similar to the Nav channels, the α1 subunit of Cav channels is organized in four homologous domains (I–IV), each containing six TM segments (S1–S6). The S1–S4 segments constitute the voltage sensor, while S5–S6 constitute the pore. Auxiliary subunits usually associate with α1, regulating channel expression and function. Cav channels are grouped into various types based on their electrophysiological and pharmacological properties and tissue distribution – L-type (Cav1 subfamily: Cav1.1-Cav1.4); P/Q-, N-, and R-types (Cav2.1, Cav2.2 and Cav2.3, respectively) and T-type (Cav3 subfamily: Cav3.1-Cav3.3). Venom toxins have played a vital role in the discovery of, and in deciphering the structure and function of, many Cav channels. Chief among them are the ω-conotoxins and ω-agatoxins.

Ω-conotoxins are ∼24–30 residues in length and contain three intramolecular disulfide bonds. They target Cav channels via blocking the ion pore. Ω-conotoxin GVIA, from the venom of Conus geographus, was the first of the ω-conotoxins to be isolated and characterized (Kerr and Yoshikami, 1984; Olivera et al., 1985). Studies with GVIA showed inhibition of Ca2+ entry (voltage-activated), and GVIA was a powerful probe to explore the presynaptic terminal, linking Cav (N-type) channels to neurotransmitter release and synaptic transmission (Kerr and Yoshikami, 1984; Olivera et al., 1984). Molecular identity of the N-type and L-type channel subunit composition was determined using GVIA binding (Williams et al., 1992).

Subsequent to GVIA, many other ω-conotoxins were identified. One of the most prominent ones is MVIIA, from the Magician’s cone snail, Conus magus (Olivera et al., 1987), which was tested and developed as a therapeutic agent against pain. Ziconotide (Prialt®) has been clinically approved for the treatment of severe chronic pain associated with cancer and neuropathies, and is currently the only venom peptide drug targeting a voltage-gated ion channel (Cav2.2) that is in clinical use (Miljanich, 2004). A more selective ω-conotoxin, CVID, was isolated from Conus catus (Lewis et al., 2000), and was being developed as leconotide for pain treatment. However, it failed clinical trials due to adverse side-effects (Kolosov et al., 2010).

Spider toxin ω-agatoxin IVA, a gating modifier toxin isolated from Agelenopsis aperta, specifically targets P/Q-type channels (Pringos et al., 2011), and was used to study the channel subunit composition (McEnery et al., 1991; Witcher et al., 1995).

Concluding Remarks

Given that there are many species whose toxic venom are yet to be fully explored, the collection of venom-derived peptides to be discovered is immense. Also, with the advent of technology in drug design, based on currently available toxin peptides, new drugs will be developed into more stable and selective biologics. While venomous species developed toxins to incapacitate prey and predators, and envenomation is a public health hazard for us humans, the toxins have proven to be an excellent source of research and therapeutic tools.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. George K. Chandy and Dr. Jeff Chang for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Funding. SB has received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement no 608765. The authors also acknowledge support from Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 2 (MOE2016-T2-2-032) and Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University Singapore Start-Up Grant to Prof. George K. Chandy.

References

- Abbas N., Belghazi M., Abdel-Mottaleb Y., Tytgat J., Bougis P. E., Martin-Eauclaire M.-F. (2008). A new Kaliotoxin selective towards Kv1.3 and Kv1.2 but not Kv1.1 channels expressed in oocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 376 525–530. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Mottaleb Y., Vandendriessche T., Clynen E., Landuyt B., Jalali A., Vatanpour H., et al. (2008). OdK2, a Kv1.3 channel-selective toxin from the venom of the Iranian scorpion Odonthobuthus doriae. Toxicon 51 1424–1430. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M. E., Bindokas V. P., Hasegawa L., Venema V. J. (1990). Omega-agatoxins: novel calcium channel antagonists of two subtypes from funnel web spider (Agelenopsis aperta) venom. J. Biol. Chem. 265 861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew W. S., Levinson S. R., Brabson J. S., Raftery M. A. (1978). Purification of the tetrodotoxin-binding component associated with the voltage-sensitive sodium channel from Electrophorus electricus electroplax membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75 2606–2610. 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S. P. H., Striessnig J., Kelly E., Marrion N. V., Peters J. A., Faccenda E., et al. (2017). The concise guide to pharmacology 2017/18: voltage-gated ion channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174 S160–S194. 10.1111/bph.13884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C. M., Bezanilla F., Rojas E. (1973). Destruction of sodium conductance inactivation in squid axons perfused with pronase. J. Gen. Physiol. 62 375–391. 10.1085/jgp.62.4.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdáany M., Batista C. V. F., Valdez-Cruz N. A., Somodi S., de la Vega R. C. R., Licea A. F., et al. (2005). Anuroctoxin, a new scorpion toxin of the α-KTx 6 subfamily, is highly selective for Kv1.3 over IKCa1 ion channels of human T lymphocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 67 1034–1044. 10.1124/mol.104.007187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartok A., Toth A., Somodi S., Szanto T. G., Hajdu P., Panyi G., et al. (2014). Margatoxin is a non-selective inhibitor of human Kv1.3 K+ channels. Toxicon 87 6–16. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneski D. A., Catterall W. A. (1980). Covalent labeling of protein components of the sodium channel with a photoactivable derivative of scorpion toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 639–643. 10.1073/pnas.77.1.639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee P., Bhattacharyya D. (2014). Therapeutic use of snake venom components: a voyage from ancient to modern India. Mini. Rev. Org. Chem. 11 45–54. 10.2174/1570193X1101140402101043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bindokas V. P., Adams M. E. (1989). ω-Aga-I: a presynaptic calcium channel antagonist from venom of the funnel web spider, Agelenopsis aperta. J. Neurobiol. 20 171–188. 10.1002/neu.480200402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans F., Rash L., Zhu S., Diochot S., Lazdunski M., Escoubas P. T., et al. (2006). Four novel tarantula toxins as selective modulators of voltage-gated sodium channel subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 69 419–429. 10.1124/mol.105.015941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan M. D., Chandy K. G. (2009). The functional network of ion channels in T lymphocytes. Immunol. Rev. 231 59–87. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00816.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candia S., Garcia M. L., Latorre R. (1992). Mode of action of iberiotoxin, a potent blocker of the large conductance Ca2+)-activated K+ channel. Biophys. J. 63 583–590. 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81630-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E., Wanke E., Prestipino G., Possani L. D., Maelicke A. (1982). Selective blockage of voltage-dependent K+ channels by a novel scorpion toxin. Nature 296 90–91. 10.1038/296090a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso F. C., Dekan Z., Rosengren K. J., Erickson A., Vetter I., Deuis J. R., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of ProTx-III [ -TRTX-Tp1a], a new voltage-gated sodium channel inhibitor from venom of the tarantula Thrixopelma pruriens. Mol. Pharmacol. 88 291–303. 10.1124/mol.115.098178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda O., Sotolongo V., Amor A. M., Stöcklin R., Anderson A. J., Harvey A. L., et al. (1995). Characterization of a potassium channel toxin from the Caribbean sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus. Toxicon 33 603–613. 10.1016/0041-0101(95)00013-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle N. A. (2003). Maurotoxin: a potent inhibitor of intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 63 409–418. 10.1124/mol.63.2.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle N. A., Strong P. N. (1986). Identification of two toxins from scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus) venom which block distinct classes of calcium-activated potassium channel. FEBS Lett. 209 117–121. 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81095-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A. (2011). Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a003947. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahine M., Plante E., Kallen R. G. (1996). Sea anemone toxin (ATX II) modulation of heart and skeletal muscle sodium channel α-subunits expressed in tsA201 cells. J. Membr. Biol. 152 39–48. 10.1007/s002329900083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Bajaj S., Chandy K. (2018). ShK toxin: history, structure and therapeutic applications for autoimmune diseases. WikiJ. Sci. 1:3 10.15347/wjs/2018.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Lu S. Q., Leipold E., Gordon D., Hansel A., Heinemann S. H. (2002). Differential sensitivity of sodium channels from the central and peripheral nervous system to the scorpion toxins Lqh-2 and Lqh-3. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16 767–770. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02142.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi V., Pennington M. W., Norton R. S., Tarcha E. J., Londono L. M., Sims-Fahey B., et al. (2012). Development of a sea anemone toxin as an immunomodulator for therapy of autoimmune diseases. Toxicon 59 529–546. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuan T., Ruixin Z., Lixin Z., Tianyi Q., Zhiwei C., Tingguo K. (2013). Potassium channels: structures, diseases, and modulators. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 83 1–26. 10.1111/cbdd.12237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang R. S., Jaffe H., Cribbs L., Perez-Reyes E., Swartz K. J. (1998). Inhibition of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels by a new scorpion toxin. Nat. Neurosci. 1 668–674. 10.1038/3669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro Mdo N., de Figueiredo S. G., Valentim A., do C., Diniz C. R., von Eickstedt V. R. D., et al. (1993). Purification and amino acid sequences of six Tx3 type neurotoxins from the venom of the Brazilian “armed” spider Phoneutria Nigriventer (keys.). Toxicon 31 35–42. 10.1016/0041-0101(93)90354-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton J., Crest M., Bouet F., Alessandri N., Gola M., Forest E., et al. (1997). A potassium-channel toxin from the sea anemone Bunodosoma granulifera, an inhibitor for Kv1 channels. Revision of the amino acid sequence, disulfide-bridge assignment, chemical synthesis, and biological activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 244 192–202. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crest M., Jacquet G., Gola M., Zerrouk H., Benslimane A., Rochat H., et al. (1992). Kaliotoxin, a novel peptidyl inhibitor of neuronal BK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels characterized from Androctonus mauretanicus venom. J. Biol. Chem. 267 1640–1647. 10.2106/JBJS.F.00758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly N. L., Ekberg J. A., Thomas L., Adams D. J., Lewis R. J., Craik D. J. (2004). Structures of μO-conotoxins from Conus marmoreus: inhibitors of tetrodotoxin (ttx)-sensitive and ttx-resistant sodium channels in mammalian sensory neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 279 25774–25782. 10.1074/jbc.M313002200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weille J. R., Schweitz H., Maes P., Tartar A., Lazdunski M. (1991). Calciseptine, a peptide isolated from black mamba venom, is a specific blocker of the L-type calcium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 2437–2440. 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuis J. R., Dekan Z., Wingerd J. S., Smith J. J., Munasinghe N. R., Bhola R. F., et al. (2017). Pharmacological characterisation of the highly Na v 1.7 selective spider venom peptide Pn3a. Sci. Rep. 7:40883. 10.1038/srep40883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diochot S., Drici M.-D., Moinier D., Fink M., Lazdunski M. (1999). Effects of phrixotoxins on the Kv4 family of potassium channels and implications for the role of I(to1) in cardiac electrogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 126 251–263. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diochot S., Schweitz H., Béress L., Lazdunski M. (1998). Sea anemone peptides with a specific blocking activity against the fast inactivating potassium channel Kv3.4. J. Biol. Chem. 273 6744–6749. 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev D., Friedrich A., Voigt N., Jost N., Wettwer E., Christ T., et al. (2005). The G protein-gated potassium current IK,ACh is constitutively active in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 112 3697–3706. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik C. A. (2017). Venom-derived peptides inhibiting Kir channels: past, present, and future. Neuropharmacology 127 161–172. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutertre S., Lewis R. J. (2010). Use of venom peptides to probe ion channel structure and function. J. Biol. Chem. 285 13315–13320. 10.1074/jbc.R109.076596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg J., Jayamanne A., Vaughan C. W., Aslan S., Thomas L., Mould J., et al. (2006). muO-conotoxin MrVIB selectively blocks Nav1.8 sensory neuron specific sodium channels and chronic pain behavior without motor deficits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 17030–17035. 10.1073/pnas.0601819103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel E. A., Warren V. A., Cohen C. J., Smith M. M., Adams M. E., Griffin P. R. (1994). Type III ω-agatoxins: a family of probes for similar binding sites on L- and N-type calcium channels. Biochemistry 33 5098–5108. 10.1021/bi00183a013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas P., Diochot S., Célérier M.-L., Nakajima T., Lazdunski M. (2002). Novel tarantula toxins for subtypes of voltage-dependent potassium channels in the Kv2 and Kv4 subfamilies. Mol. Pharmacol. 62 48–57. 10.1124/mol.62.1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinspach M., Xu Q., Piekarz A. D., Fellows R., Hagan R., Gibbs A., et al. (2017). Insensitivity to pain induced by a potent selective closed-state Nav1.7 inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 7:39662. 10.1038/srep39662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewiak J., Azam L., Imperial J., Walewska A., Green B. R., Bandyopadhyay P. K., et al. (2014). A disulfide tether stabilizes the block of sodium channels by the conotoxin O -GVIIJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 2758–2763. 10.1073/pnas.1324189111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B., Peigneur S., Tytgat J., Zhu S. (2010). A potent potassium channel blocker from Mesobuthus eupeus scorpion venom. Biochimie 92 1847–1853. 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M. L., Garcia-Calvo M., Hidalgo P., Lee A., MacKinnon R. (1994). Purification and characterization of three inhibitors of voltage-dependent K+ channels from Leiurus quinquestriatus var. hebraeus Venom. Biochemistry 33 6834–6839. 10.1021/bi00188a012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M. L., Knaus H. G., Munujos P., Slaughter R. S., Kaczorowski G. J. (1995). Charybdotoxin and its effects on potassium channels. Am. J. Physiol. 269 C1–C10. 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Calvo M., Leonard R. J., Novick J., Stevens S. P., Schmalhofer W., Kaczorowski G. J., et al. (1993). Purification, characterization, and biosynthesis of margatoxin, a component of Centruroides margaritatus venom that selectively inhibits voltage-dependent potassium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 268 18866–18874. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Valdes J., Zamudio F. Z., Toro L., Possan L. D. (2001). Slotoxin, αKTx1.11, a new scorpion peptide blocker of MaxiK channels that differentiates between α and α+β (β1 or β4) complexes. FEBS Lett. 505 369–373. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02791-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanshani S., Wulff H., Miller M. J., Rohm H., Neben A., Gutman G. A., et al. (2000). Up-regulation of the IKCa1 potassium channel during T-cell activation: molecular mechanism and functional consequences. J. Biol. Chem. 275 37137–37149. 10.1074/jbc.M003941200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S. A., Bayliss D. A., Kim D., Lesage F., Plant L. D., Rajan S. (2005). International union of pharmacology. LV. nomenclature and molecular relationships of two-p potassium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 57 527–540. 10.1124/pr.57.4.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S., Nguyen A. N., Aiyar J., Hanson D. C., Mather R. J., Gutman G. A., et al. (1994). Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol. Pharmacol. 45 1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne R. P., Catterall W. A. (1981). Purification of the saxitoxin receptor of the sodium channel from rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78 4620–4624. 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N., Yamashita T., Tsuruzoe N. (2006). Tertiapin, a selective IKACh blocker, terminates atrial fibrillation with selective atrial effective refractory period prolongation. Pharmacol. Res. 54 136–141. 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H., Inanobe A., Furutani K., Murakami S., Findlay I., Kurachi Y. (2010). Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 90 291–366. 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo P., MacKinnon R. (1995). Revealing the architecture of a K+ channel pore through mutant cycles with a peptide inhibitor. Science 268 307–310. 10.1126/science.7716527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. (1971). The permeability of the sodium channel to organic cations in myelinated nerve. J. Gen. Physiol. 58 599–619. 10.1085/jgp.58.6.599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. (1975). Ionic selectivity, saturation, and block in sodium channels. A four- barrier model. J. Gen. Physiol. 66 535–560. 10.1085/jgp.66.5.535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. (1977). Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug- receptor reaction. J. Gen. Physiol. 69 497–515. 10.1085/jgp.69.4.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K., Nichols C. G., Lederer W. J., Lytton J., Vassilev P. M., Kanazirska M. V., et al. (1993). Cloning and expression of an inwardly rectifying ATP-regulated potassium channel. Nature 362 31–38. 10.1038/362031a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugues M., Romey G., Duval D., Vincent J. P., Lazdunski M. (1982). Apamin as a selective blocker of the calcium-dependent potassium channel in neuroblastoma cells: voltage-clamp and biochemical characterization of the toxin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79 1308–1312. 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imredy J. P., Chen C., MacKinnon R. (1998). A snake toxin inhibitor of inward rectifier potassium channel ROMK1. Biochemistry 37 14867–14874. 10.1021/bi980929k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W., Lu Z. (1998). A novel high-affinity inhibitor for inward-rectifier K+ channels. Biochemistry 37 13291–13299. 10.1021/bi981178p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouirou B., Mosbah A., Visan V., Grissmer S., M’Barek S., Fajloun Z., et al. (2004). Cobatoxin 1 from Centruroides noxius scorpion venom: chemical synthesis, three-dimensional structure in solution, pharmacology and docking on K+ channels. Biochem. J. 377 37–49. 10.1042/BJ20030977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman K., Pennington M. W., Lanigan M. D., Nguyen A., Rauer H., Mahnir V., et al. (1998). Shk-Dap22, a potent Kv1.3-specific immunosuppressive polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 273 32697–32707. 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. (1949). Les constantes electriques de la membrane du muscle. Arch. Sci. Physiol. 3 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr L. M., Yoshikami D. (1984). A venom peptide with a novel presynaptic blocking action. Nature 308 282–284. 10.1038/308282a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimm T., Bean B. P. (2014). Inhibition of A-type potassium current by the peptide toxin SNX-482. J. Neurosci. 34 9182–9189. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0339-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G. F. (2011). Venoms as a platform for human drugs: translating toxins into therapeutics. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 11 1469–1484. 10.1517/14712598.2011.621940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolosov A., Goodchild C. S., Cooke I. (2010). CNSB004 (leconotide) causes antihyperalgesia without side effects when given intravenously: a comparison with ziconotide in a rat model of diabetic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 11 262–273. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolkova Y. V., Kozlov S. A., Lipkin A. V., Pluzhnikov K. A., Hadley J. K., Filippov A. K., et al. (2001). An ERG channel inhibitor from the scorpion Buthus eupeus. J. Biol. Chem. 276 9868–9876. 10.1074/jbc.M005973200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschak A., Bugianesi R. M., Mitterdorfer J., Kaczorowski G. J., Garcia M. L., Knaus H.-G. (1998). Subunit composition of brain voltage-gated potassium channels determined by hongotoxin-1, a novel peptide derived from Centruroides limbatus Venom. J. Biol. Chem. 273 2639–2644. 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y., Baldwin T. J., Nung Jan Y., Jan L. Y. (1993). Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature 362 127–133. 10.1038/362127a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmenkov A. I., Krylov N. A., Chugunov A. O., Grishin E. V., Vassilevski A. A. (2016). Kalium: a database of potassium channel toxins from scorpion venom. Database 2016:baw056. 10.1093/database/baw056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe R. A., Defeo P. A., Davison M. D., Young J., Herman J. L., Spreen R. C., et al. (1993). Isolation and pharmacological characterization of omega-grammotoxin SIA, a novel peptide inhibitor of neuronal voltage-sensitive calcium channel responses. Mol. Pharmacol. 44 451–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun B., Romi-Lebrun R., Martin-Eauclaire M. F., Yasuda A., Ishiguro M., Oyama Y., et al. (1997). A four-disulphide-bridged toxin, with high affinity towards voltage-gated K+ channels, isolated from Heterometrus spinnifer (Scorpionidae) venom. Biochem. J. 328 321–327. 10.1042/bj3280321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte C., Ferrat G., Fajloun Z., Van Rietschoten J., Rochat H., Martin-Eauclaire M. F., et al. (1999). Chemical synthesis and structure-activity relationships of Ts κ, a novel scorpion toxin acting on apamin-sensitive SK channel. J. Pept. Res. 54 369–376. 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipold E., De Bie H., Zorn S., Borges A., Olivera B. M., Terlau H., et al. (2007). μo-Conotoxins inhibit Navchannels by interfering with their voltage sensors in domain-2. Channels 1 253–262. 10.4161/chan.4847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. J., Nielsen K. J., Craik D. J., Loughnan M. L., Adams D. A., Sharpe I. A., et al. (2000). Novel ω-conotoxins from Conus catus discriminate among neuronal calcium channel subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 275 35335–35344. 10.1074/jbc.M002252200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Chen R., Chung S. H. (2016). Molecular dynamics of the honey bee toxin tertiapin binding to Kir3.2. Biophys. Chem. 219 43–48. 10.1016/j.bpc.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Wu J. X., Ding D., Cheng J., Gao N., Chen L. (2017). Structure of a pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Cell 168 101.e10–110.e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Ma Y., Yin S., Zhao R., Fan S., Hu Y., et al. (2009). Molecular cloning and functional identification of a new K+ channel blocker, LmKTx10, from the scorpion Lychas mucronatus. Peptides 30 675–680. 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Dai J., Chen Z., Hu W., Xiao Y., Liang S. (2003). Isolation and characterization of hainantoxin-IV, a novel antagonist of tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels from the Chinese bird spider Selenocosmia hainana. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60 972–978. 10.1007/s00018-003-2354-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S. B., Campbell E. B., Mackinnon R. (2005). Voltage sensor of Kv1.2: structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science 309 903–908. 10.1126/science.1116270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. (2004). Mechanism of rectification in inward-rectifier K+ channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66 103–129. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.150822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., MacKinnon R. (1997). Purification, characterization, and synthesis of an inward-rectifier K+ channel inhibitor from scorpion venom. Biochemistry 36 6936–6940. 10.1021/bi9702849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Ramírez K., Bartok A., Restano-Cassulini R., Quintero-Hernández V., Coronas F. I. V., Christensen J., et al. (2014). Structure, molecular modeling, and function of the novel potassium channel blocker urotoxin isolated from the venom of the Australian Scorpion <em>Urodacus yaschenkoi</em>. Mol. Pharmacol. 86 28–41. 10.1124/mol.113.090183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R. (1991). Determination of the subunit stoichiometry of a voltage-activated potassium channel. Nature 350 232–235. 10.1038/350232a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens C., Cuypers E., Amininasab M., Jalali A., Vatanpour H., Tytgat J. (2006). Potent modulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.7 by OD1, a toxin from the scorpion Odonthobuthus doriae. Mol. Pharmacol. 70 405–414. 10.1124/mol.106.022970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough S. I., Lampe R. A., Keith R. A., Bean B. P. (1997). Voltage-dependent inhibition of N- and P-type calcium channels by the peptide toxin omega-grammotoxin-SIA. Mol. Pharmacol. 52 1095–1104. 10.1124/mol.52.6.1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEnery M. W., Snowman A. M., Sharp A. H., Adams M. E., Snyder S. H. (1991). Purified omega-conotoxin GVIA receptor of rat brain resembles a dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type calcium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 11095–11099. 10.1243/09544062JMES1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen C. (2017). Comprehensive Toxicology, 3rd Edn Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton R. E., Warren V. A., Kraus R. L., Hwang J. C., Liu C. J., Dai G., et al. (2002). Two tarantula peptides inhibit activation of multiple sodium channels. Biochemistry 41 14734–14747. 10.1021/bi026546a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miljanich G. (2004). Ziconotide: neuronal calcium channel blocker for treating severe chronic pain. Curr. Med. Chem. 11 3029–3040. 10.2174/0929867043363884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian N. A., Gibbs A., Shih A. Y., Liu Y., Neff R. A., Sutton S. W., et al. (2013). Analysis of the structural and molecular basis of voltage-sensitive sodium channel inhibition by the spider toxin huwentoxin-IV (μ-TRTX-Hh2a). J. Biol. Chem. 288 22707–22720. 10.1074/jbc.M113.461392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz I. M., Venema V. J., Swiderek K. M., Lee T. D., Bean B. P., Adams M. E. (1992). P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin ω-Aga-IVA. Nature 355 827–829. 10.1038/355827a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran Y., Gordon D., Gurevitz M. (2009). Sea anemone toxins affecting voltage-gated sodium channels – molecular and evolutionary features. Toxicon 54 1089–1101. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouhat S., Visan V., Ananthakrishnan S., Wulff H., Andreotti N., Grissmer S., et al. (2005). K(+) channel types targeted by synthetic OSK1, a toxin from Orthochirus scrobiculosus scorpion venom. Biochem. J. 385 95–104. 10.1042/BJ20041379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. K., Ligutti J., Liu D., Zou A., Poppe L., Li H., et al. (2015). Engineering potent and selective analogues of GpTx-1, a tarantula venom peptide antagonist of the Na(V)1.7 sodium channel. J. Med. Chem. 58 2299–2314. 10.1021/jm501765v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najet S., Delavar S., Imen C., Saoussen M., Hafedh M., Lamia B., et al. (2008). Hemitoxin, the first potassium channel toxin from the venom of the Iranian scorpion Hemiscorpius lepturus. FEBS J. 275 4641–4650. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06607.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb R., Szoke B., Palma A., Wang G., Chen X. H., Hopkins W., et al. (1998). Selective peptide antagonist of the class E calcium channel from the venom of the tarantula Hysterocrates gigas. Biochemistry 37 15353–15362. 10.1021/bi981255g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novello J. C., Arantes E. C., Varanda W. A., Oliveira B., Giglio J. R., Marangoni S. (1999). TsTX-IV, a short chain four-disulfide-bridged neurotoxin from Tityus serrulatus venom which acts on Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Toxicon 37 651–660. 10.1016/S0041-0101(98)00206-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo T., Yamazaki J., Kitamura K. (2010). Tarantula Toxin ProTx-I differentiates between human t-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels Cav3.1 and Cav3.2. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 112 452–458. 10.1254/jphs.09356FP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira J. S., Redaelli E., Zaharenko A. J., Cassulini R. R., Konno K., Pimenta D. C., et al. (2004). Binding specificity of sea anemone toxins to Nav 1.1-1.6 sodium channels. Unexpected contributions from differences in the IV/S3-S4 outer loop. J. Biol. Chem. 279 33323–33335. 10.1074/jbc.M404344200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera B. M., Cruz L. J., de Santos V., LeCheminant G. W., Griffin D., Zeikus R., et al. (1987). Neuronal calcium channel antagonists. Discrimination between calcium channel subtypes using omega-conotoxin from Conus magus venom. Biochemistry 26 2086–2090. 10.1021/bi00382a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera B. M., Gray W. R., Zeikus R., McIntosh J. M., Varga J., Rivier J., et al. (1985). Peptide neurotoxins from fish-hunting cone snails. Science 230 1338–1343. 10.1126/science.4071055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M., Cruz L. J., Gray W. R., Luque F. A. (1984). Purification and sequence of a presynaptic peptide toxin from Conus geographus Venom. Biochemistry 23 5087–5090. 10.1021/bi00317a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera B. M., Miljanich G. P., Ramachandran J., Adams M. E. (1994). Calcium channel diversity and neurotransmitter release: the ω-Conotoxins and ω-Agatoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63 823–867. 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera B. M., Rivier J., Clark C., Ramilo C. A., Corpuz G. P., Abogadie F. C., et al. (1990). Diversity of Conus neuropeptides. Science 249 257–263. 10.1126/science.2165278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orts D. J. B., Peigneur S., Madio B., Cassoli J. S., Montandon G. G., Pimenta A. M. C., et al. (2013). Biochemical and electrophysiological characterization of two sea anemone type 1 potassium toxins from a geographically distant population of Bunodosoma caissarum. Mar. Drugs 11 655–679. 10.3390/md11030655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh J., Scheuer T., Zheng N., Catterall W. A. (2011). The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 475 353–358. 10.1038/nature10238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedarzani P., D’Hoedt D., Doorty K. B., Wadsworth J. D. F., Joseph J. S., Jeyaseelan K., et al. (2002). Tamapin, a venom peptide from the Indian red scorpion (Mesobuthus tamulus) that targets small conductance Ca2+-activated K+channels and after hyperpolarization currents in central neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 277 46101–46109. 10.1074/jbc.M206465200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng K., Shu Q., Liu Z., Liang S. (2002). Function and solution structure of huwentoxin-IV, a potent neuronal tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive sodium channel antagonist from Chinese bird spider Selenocosmia huwena. J. Biol. Chem. 277 47564–47571. 10.1074/jbc.M204063200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington M. W., Byrnes M. E., Zaydenberg I., Khaytin I., De Chastonay J., Krafte D. S., et al. (1995). Chemical synthesis and characterization of ShK toxin: a potent potassium channel inhibitor from a sea anemone. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 46 354–358. 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1995.tb01068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringos E., Vignes M., Martinez J., Rolland V. (2011). Peptide neurotoxins that affect voltage-gated calcium channels: a close-up on ω-agatoxins. Toxins 3 17–42. 10.3390/toxins3010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucca M. B., Cerni F. A., Cordeiro F. A., Peigneur S., Cunha T. M., Tytgat J., et al. (2016). Ts8 scorpion toxin inhibits the Kv4.2 channel and produces nociception in vivo. Toxicon 119 244–252. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale D. S., McPhee J. C., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (1996). Common molecular determinants of local anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, and anticonvulsant block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 9270–9275. 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahnama S., Deuis J. R., Cardoso F. C., Ramanujam V., Lewis R. J., Rash L. D., et al. (2017). The structure, dynamics and selectivity profile of a NaV 1.7 potency-optimised huwentoxin-IV variant. PLoS One 12:e0173551. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer H., Lanigan M. D., Pennington M. W., Aiyar J., Ghanshani S., Cahalan M. D., et al. (2000). Structure-guided transformation of charybdotoxin yields an analog that selectively targets Ca2+-activated over voltage-gated K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 275 1201–1208. 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli E., Cassulini R. R., Silva D. F., Clement H., Schiavon E., Zamudio F. Z., et al. (2010). Target promiscuity and heterogeneous effects of tarantula venom peptides affecting Na+ and K+ ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 285 4130–4142. 10.1074/jbc.M109.054718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell J. D., Lund P. E., Linley J. E., Metcalfe J., Burmeister N., Sridharan S., et al. (2013). Potency optimization of Huwentoxin-IV on hNav1.7: a neurotoxin TTX-S sodium-channel antagonist from the venom of the Chinese bird-eating spider Selenocosmia huwena. Peptides 44 40–46. 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B., Owen D. G. (1993). Pharmacology of a cloned potassium channel from mouse brain (MK-1) expressed in CHO cells: effects of blockers and an “inactivation peptide”. Br. J. Pharmacol. 109 725–735. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13634.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romi-Lebrun R., Lebrun B., Martin-Eauclaire M. F., Ishiguro M., Escoubas P., Wu F. Q., et al. (1997). Purification, characterization, and synthesis of three novel toxins from the Chinese scorpion Buthus martensi, which act on K+ channels. Biochemistry 36 13473–13482. 10.1021/bi971044w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong M., Chen J., Tao H., Wu Y., Jiang P., Lu M., et al. (2011). Molecular basis of the tarantula toxin jingzhaotoxin-III ( -TRTX-Cj1 ) interacting with voltage sensors in sodium channel subtype Nav1.5. FASEB J. 25 3177–3185. 10.1096/fj.10-178848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryadh K., Kamel M., Marcel C., Hervé D., Razika O., Marie-France M., et al. (2018). Chemical synthesis and characterization of maurotoxin, a short scorpion toxin with four disulfide bridges that acts on K+ channels. Eur. J. Biochem. 242 491–498. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0491r.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti M. C., Johnson J. H., Hammerland L. G., Kelbaugh P. R., Volkmann R. A., Saccomano N. A., et al. (1997). Heteropodatoxins: peptides isolated from spider venom that block Kv4.2 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 51 491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrah M., Amor M., Guillaume S., Ziad F., Timoteo O., Hervé R., et al. (2003). Synthesis and characterization of Pi4, a scorpion toxin from Pandinus imperator that acts on K+ channels. Eur. J. Biochem. 270 3583–3592. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalhofer W. A., Calhoun J., Burrows R., Bailey T., Kohler M. G., Weinglass A. B., et al. (2008). ProTx-II, a selective inhibitor of NaV1.7 sodium channels, blocks action potential propagation in nociceptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 74 1476–1484. 10.1124/mol.108.047670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidach S. S., Mintz I. M. (2002). Kurtoxin, a gating modifier of neuronal high- and low-threshold Ca channels. J. Neurosci. 22 2023–2034. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02023.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A. O., Peigneur S., Diniz M. R. V., Tytgat J., Beirão P. S. L. (2012). Inhibitory effect of the recombinant Phoneutria nigriventer Tx1 toxin on voltage-gated sodium channels. Biochimie 94 2756–2763. 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson R., Marshall J., Smith J. S., Williams J. B., Boyle M. B., Folander K., et al. (1990). Cloning and expression of cDNA and genomic clones encoding three delayed rectifier potassium channels in rat brain. Neuron 4 929–939. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90146-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz K. J., MacKinnon R. (1995). An inhibitor of the Kv2.1 potassium channel isolated from the venom of a Chilean tarantula. Neuron 15 941–949. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90184-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs Z., Toups M., Kollewe A., Johnson E., Cuello L. G., Driessens G., et al. (2009). A designer ligand specific for Kv1.3 channels from a scorpion neurotoxin-based library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 22211–22216. 10.1073/pnas.0910123106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H., Chen J. J., Xiao Y. C., Wu Y. Y., Su H. B., Li D., et al. (2013). Analysis of the interaction of tarantula toxin jingzhaotoxin-III (β-TRTX-Cj1α) with the voltage sensor of Kv2.1 uncovers the molecular basis for cross-activities on Kv2.1 and Nav1.5 channels. Biochemistry 52 7439–7448. 10.1021/bi4006418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H., Chen X., Deng M., Xiao Y., Wu Y., Liu Z., et al. (2016). Interaction site for the inhibition of tarantula Jingzhaotoxin-XI on voltage-gated potassium channel Kv2.1. Toxicon 124 8–14. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarcha E. J., Chi V., Muñ;oz-Elías E. J., Bailey D., Londono L. M., Upadhyay S. K., et al. (2012). Durable pharmacological responses from the peptide ShK-186, a specific Kv1.3 channel inhibitor that suppresses T cell mediators of autoimmune disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 342 642–653. 10.1124/jpet.112.191890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichert R. W., Raghuraman S., Memon T., Cox J. L., Foulkes T., Rivier J. E., et al. (2012). Characterization of two neuronal subclasses through constellation pharmacology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 12758–12763. 10.1073/pnas.1209759109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undheim E. A. B., Mobli M., King G. F. (2016). Toxin structures as evolutionary tools: using conserved 3D folds to study the evolution of rapidly evolving peptides. BioEssays 38 539–548. 10.1002/bies.201500165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utkin Y. N. (2015). Animal venom studies: current benefits and future developments. World J. Biol. Chem. 6 28–33. 10.4331/wjbc.v6.i2.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg J. I., Perry M. D., Perrin M. J., Mann S. A., Ke Y., Hill A. P. (2012). hERG K+ channels: structure, function, and clinical significance. Physiol. Rev. 92 1393–1478. 10.1152/physrev.00036.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga Z., Gurrola-Briones G., Papp F., Rodríguez de la Vega R. C., Pedraza-Alva G., Tajhya R. B., et al. (2012). Vm24, a natural immunosuppressive peptide, potently and selectively blocks Kv1.3 Potassium Channels of Human T Cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 82 372–382. 10.1124/mol.112.078006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter I., Dekan Z., Knapp O., Adams D. J., Alewood P. F., Lewis R. J. (2012). Isolation, characterization and total regioselective synthesis of the novel μo-conotoxin MfVIA from Conus magnificus that targets voltage-gated sodium channels. Biochem. Pharmacol. 84 540–548. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K. (2011). Targeting GIRK channels for the development of new therapeutic agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2:64. 10.3389/fphar.2011.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Long C., Liu W., Xu C., Zhang M., Li Q., et al. (2018). Novel sodium channel inhibitor from leeches. Front. Pharmacol. 9:186. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Shen B., Guo M., Lou X., Duan Y., Cheng X. P., et al. (2005). Blocking effect and crystal structure of natrin toxin, a cysteine-rich secretory protein from Naja atra venom that targets the BKCa channel. Biochemistry 44 10145–10152. 10.1021/bi050614m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Umetsu Y., Gao B., Ohki S., Zhu S. (2015). Mesomartoxin, a new Kv1.2-selective scorpion toxin interacting with the channel selectivity filter. Biochem. Pharmacol. 93 232–239. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whorton M. R., MacKinnon R. (2011). Crystal structure of the mammalian GIRK2 K+ channel and gating regulation by G-proteins, PIP(2) and sodium. Cell 147 199–208. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. E., Brust P. F., Feldman D. H., Patthi S., Simerson S., Maroufi A., et al. (1992). Structure and functional expression of an ω-conotoxin-sensitive human N-type calcium channel. Science 257 389–395. 10.1126/science.1321501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. J., Yoshikami D., Azam L., Gajewiak J., Olivera B. M., Bulaj G., et al. (2011). -Conotoxins that differentially block sodium channels NaV1.1 through 1.8 identify those responsible for action potentials in sciatic nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 10302–10307. 10.1073/pnas.1107027108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witcher D. R., De Waard M., Liu H., Pragnell M., Campbell K. P. (1995). Association of native Ca2+ channel β subunits with the α1 subunit interaction domain. J. Biol. Chem. 270 18088–18093. 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Bingham J. P., Zhu W., Moczydlowski E., Liang S., Cummins T. R. (2008). Tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibits neuronal sodium channels by binding to receptor site 4 and trapping the domain II voltage sensor in the closed configuration. J. Biol. Chem. 283 27300–27313. 10.1074/jbc.M708447200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Jackson J. O., Liang S., Cummins T. R. (2011). Common molecular determinants of tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibition of Na+ channel voltage sensors in domains II and IV. J. Biol. Chem. 286 27301–27310. 10.1074/jbc.M111.246876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Adams M. E. (2000). The spider toxin ω-Aga IIIA defines a high affinity site neuronal high voltage-activated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 275 21309–21316. 10.1074/jbc.M000212200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Herrington J., Goldberg E., Dulski P. M., Bugianesi R. M., Slaughter R. S., et al. (2005). <em>Stichodactyla helianthus</em> peptide, a pharmacological tool for studying Kv3.2 channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 67 1513–1521. 10.1124/mol.105.011064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Xiao Y., Kang D., Liu J., Li Y., Undheim E. A. B., et al. (2013). Discovery of a selective NaV1.7 inhibitor from centipede venom with analgesic efficacy exceeding morphine in rodent pain models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 17534–17539. 10.1073/pnas.1306285110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J., Chen X., Li H., Zhou Y., Yao L., Wu G., et al. (2005). BmP09, a “long chain” scorpion peptide blocker of BK channels. J. Biol. Chem. 280 14819–14828. 10.1074/jbc.M412735200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G. (2002). The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives. Nature 419 35–42. 10.1038/nature00978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C., Liao Z., Zeng X., Dai L., Kuang F., Liang S. (2007). Jingzhaotoxin-XII, a gating modifier specific for Kv4.1 channels. Toxicon 50 646–652. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharenko A. J., Schiavon E., Ferreira W. A., Lecchi M., Freitas J. C., De Richardson M., et al. (2012). Characterization of selectivity and pharmacophores of type 1 sea anemone toxins by screening seven Navsodium channel isoforms. Peptides 34 158–167. 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Deng M., Lin Y., Yuan C., Pi J., Liang S. (2007). Isolation and characterization of Jingzhaotoxin-V, a novel neurotoxin from the venom of the spider Chilobrachys jingzhao. Toxicon 49 388–399. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerrouk H., Mansuelle P., Benslimane A., Rochat H., Martin-Eauclaire M. F. (1993). Characterization of a new leiurotoxin I-like scorpion toxin. PO5from Androctonus mauretanicus mauretanicus. FEBS Lett. 320 189–192. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80583-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. M., Wilson M. J., Azam L., Gajewiak J., Rivier J. E., Bulaj G., et al. (2013). Co-expression of NaVβ subunits alters the kinetics of inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels by pore-blocking μ-conotoxins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 168 1597–1610. 10.1111/bph.12051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]