Abstract

Purpose:

Intraoperative molecular imaging (IMI) is an emerging technology used to locate pulmonary adenocarcinomas and identify positive margins during surgery. Background noise and tissue autofluorescence have been major obstacles. The goal of this study is to optimize the image quality of Folate Receptor-alpha (FRα) targeted IMI of pulmonary adenocarcinomas by modifying emission data.

Procedures:

A total of 15 lung cancer patients were enrolled in a pilot study. In the first cohort, FRα upregulation within pulmonary adenocarcinoma tumors was confirmed by analyzing specimens from five pulmonary adenocarcinoma patients with flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Next, in a cohort of five additional patients, autofluorescence of intrathoracic structures and tissues was quantified. Lastly, five patients with tumors at various depths from the pleural surface were enrolled and received the FRα-targeted optical contrast agent, EC17. In this final cohort, resected lung adenocarcinomas were imaged at wide range of fluorescence exposure times (0 to 200 milliseconds), various laser powers and with unique filter configurations. Tumor-to-noise ratio (TNR) for images was generated using region of interest software.

Results:

Lung adenocarcinomas highly express FRα. Significant autofluorescence from native thoracic tissues was found with the highest fluorescent signals at the bronchial stump (547±98, range 423—699), the pulmonary artery (267±64, range 200—374), and cortical bone (266±17, range 243—287). High levels of autofluorescence were appreciated after systemic administration of EC17; however, TNR was improved by altering exposure settings at the time of the imaging. Optimal fluorescent exposure time occurs at of 40 milliseconds (25 frames per second).

Conclusions:

Exposure properties can be manipulated to maximize TNR thus allowing for successful intraoperative detection of lung adenocarcinomas during surgery. Optimization of the conditions for intraoperative molecular imaging sets the stage for future clinical trials utilizing targeted IMI techniques which can aid the surgeon at the time of cancer resection.

Introduction

Nearly 80,000 patients undergo attempted curative pulmonary resection for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) each year [1–2]. In the setting of early stage disease, approximately 15% of patients develop local or regional recurrences [3–5]. Recurrence rates exceed 70% in patients presenting with advanced disease stages [6]. These post-operative cancer recurrences are the direct result of incomplete removal of NSCLC disease burden at the time of resection. In hopes of decreasing recurrence rates, many groups have become interested in intraoperative adjuncts that can assist the thoracic surgeon in better detecting and more completely removing tumor burden [7–8].

Intraoperative molecular imaging (IMI) has been proposed to enhance the ability to accomplish complete resection of pulmonary tumors at the time of resection. IMI broadly refers to advanced imaging approaches that utilize fluorescent contrast agents (targeted or non-targeted) which accumulate in neoplastic lesions and provide visual enhancement with use of an imaging device. Multiple human clinical trials have found IMI to be promising in detecting malignancies of a variety of tumor histologies including glioma and ovarian carcinoma [9–10]. Our group has similarly obtained encouraging preliminary evidence utilizing IMI to localize small NSCLC nodules within the lung parenchyma [11–12]. Although encouraging, high “false-positive” rates remain a limitation in most studies [13].

False-positive fluorescent signal, also known as “noise”, is the result of fluorescent emission from non-cancerous tissues and can be broadly explained by two phenomena. The first is “background”, which describes the scenario of fluorescent signal emitted from non-specific accumulation of the contrast agent in non-cancerous tissue (lung parenchyma, granuloma, edematous tissue, etc). The second source of false-positivity is “autofluorescence”, or the propensity of many human tissues to be naturally fluorescent in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectra due to absorbance and emission from biologic chromophores (eg hemoproteins, collagen, porphyrins, etc) [14–15].

Ideally, in order to maximize IMI, both background and autofluorescence must be minimized. One approach to minimize background is by targeting a contrast agent to a receptor selectively expressed on the malignant tissue of interest. In the case of NSCLC, one potential target is the folate receptor alpha (FRα), which is upregulated in approximately 85% of lung adenocarcinomas. FRα and binds serum folate more avidly than normal pulmonary epithelial cells [16–19]. FRα is otherwise expressed the proximal tubules of the kidneys, activated macrophages, and in the choroid plexus.

Our group has recently begun experiments utilizing a FRα-targeted optical contrast agent for IMI. This is a folate-fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate more commonly known as EC17. Structurally, EC17 consists of a folate molecule bound to a visible wavelength compound (FITC) and has an excitation/emission wavelength of 490nm/521nm, respectively. In Phase I/II investigations, EC17 has been found to be safe and effective in non-thoracic malignancies, such as ovarian cancer and renal cell carcinoma, which also express high levels of FRα [9, 20–21].

The goal of this work is to standardize and optimize procedures for the detection of human pulmonary adenocarcinomas using FRα-targeted IMI. We begin by characterizing the distribution of the FRα on pulmonary adenocarcinomas as compared to benign lung parenchyma. Second, we quantify the amount of autofluorescence encountered in the human chest without a contrast agent present. Lastly, we describe the results of a pilot study aimed to maximize tumor to noise fluorescence.

Methods

Folate-FITC (EC17)

Folate hapten (vitamin B9) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were conjugated through an ethylenediamine spacer to produce EC17 as previously described [22]. EC17 has a molecular weight of 917 kDa. FITC is a derivative of fluorescein functionalized with an isothiocyanate reactive group. FITC is excited in the 465–490 nm wavelength and emits light in the 520–530 nm range which falls within the visible light spectrum. The folate-FITC conjugate forms a negatively charged fluorescent molecule that specifically targets cell-surface FRα and is subsequently internalized into the cytoplasm.

All vials of EC17 were supplied by On Target Laboratories, Inc. (West Lafayette, IN). 0.1 mg/kg EC17 was dissolved in 10 mL of normal saline and injected over 10 minutes via peripheral vein two hours prior to operation.

Study Design

This clinical study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Review Boards; informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients with a biopsy-proven lung adenocarcinoma were eligible for this study. All patients underwent preoperative staging with chest computed tomography (CT) scan and 18-FDG-PET scan, which showed no evidence of extrathoracic metastatic disease. No patients received preoperative chemotherapy or radiation. All patients were instructed to stop folate-containing vitamins one week before surgery. All preoperative tissue biopsies were interpreted at our institution by a pathologist specializing in thoracic disease. Patients scheduled for a video-assisted thoracoscopic or robot-assisted pulmonary resection were excluded due to limitations of our imaging equipment.

In this study, 15 patients with biopsy proven lung adenocarcinoma were scheduled to undergo open lung resection. In the first cohort of 5 patients, tumor and surrounding benign parenchyma was obtained at the time of thoracotomy. Tissues were analyzed for FRα detection (see flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry below for details).

In a subsequent group of patients (n=5), autofluorescence was assess by imaging thoracic structures (bronchus, bone, muscle, benign parenchyma, tumor) in the absence of contrast. In the final cohort, two hours prior to surgery, 5 patients were systemically infused with 0.1mg/kg of a folate-FITC (courtesy, On Target Laboratories, Inc., Lafayette, IN). During thoracotomy, the primary lesion was located using traditional methods. The operating room lights were dimmed, and the intraoperative fluorescent imaging system was sterilely draped and positioned above the chest using a custom designed positioning device (BioMediCon, Moorestown, NJ). The chest cavity, primary cancer and surrounding parenchyma were all imaged and fluorescence was recorded. Lung resection specimens were removed and the imaged again ex vivo on the back table.

Imaging Equipment

The “Fluocam” is a home built digital imaging system based on a dual CCD camera system previously described [23–24] (BioVision Technologies Inc, Exeter, PA). The system uses two QIClick™ digital CCD cameras from QImaging (British Columbia, Canada), one for white brightfield and one for fluorescence overlay. The cameras have a 696 × 520-pixel resolution and have a fluorescence exposure time of 20–200 ms. Each camera runs on 6 W supplied through a firewire interface. The light source was a Spectra X Light Engine (Lumencor, Inc., Beavertown, OR). Cameras were aligned so an overlay of the two images allowed for precise localization of the fluorescent probes within the tissue. The imaging equipment was mounted inside a 16’x7’x24’ stainless steel case with handles that could be made sterile using operating room light handles. The system was controlled by Metamorph® (Molecular Devices LLC). Fluorescence exposure was controlled using the computer software. Output was displayed as (i) pure fluorescence, (ii) pure bright field and (iii) fused images.

Microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed using an Olympus IX51 fluorescent microscope equipped with a fluorescein specific filter set (Chroma® 49012).

Immunohistochemical Staining

Biopsy specimens were harvested and placed in Tissue-Tek OCT and stored at −80°C or in formalin for paraffin sectioning. Frozen tumor sections were prepared as previously described [25]. To detect FRα and FITC, the monoclonal mouse antibody Mab343 (Morphotek Inc., PA) and monoclonal mouse antibody Mab10257 (Abcam ®) were used respectively.

Flow Cytometry

Surgically-resected fresh lung tumors from patients were processed within 30 minutes of removal from the patient. Specimen were prepared into single cell suspension as previously described [26]. Briefly, tumors were trimmed, sliced into small pieces, and enzymatically digested with a cocktail composed of multiple collagenases and elastase (Worthington) for one hour at 37 Co with shaking. After RBC lysis, cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. If the viability of cells was less than 80%, dead cells were eliminated using a “dead cell removal kit” (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Germany). Flow cytometric analysis was performed per standard protocols. Matched isotype antibodies were used as controls. Data was acquired using the FACSCalibur™ or LSRFortessa™ flow cytometers (both from BD Biosciences) and was analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Data Acquisition and Statistics

Region-of-interest software and HeatMap plugin within ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/; public domain free software developed by National Institutes of Health) was used to quantitate tissue fluorescence. Background readings were taken from adjacent normal lung tissue in order to generate a tumor-to-noise ratio (TNR).TNR was calculated using the following equation:

Results are described as mean±standard error of mean unless otherwise noted. Statistical significance was assessed using the student t-test, chi-squared test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Statistics were considered significant at p values ≤ 0.05. All calculations were performed in Stata ® v14.

Results

FRα is present on both lung adenocarcinomas and benign lung parenchyma

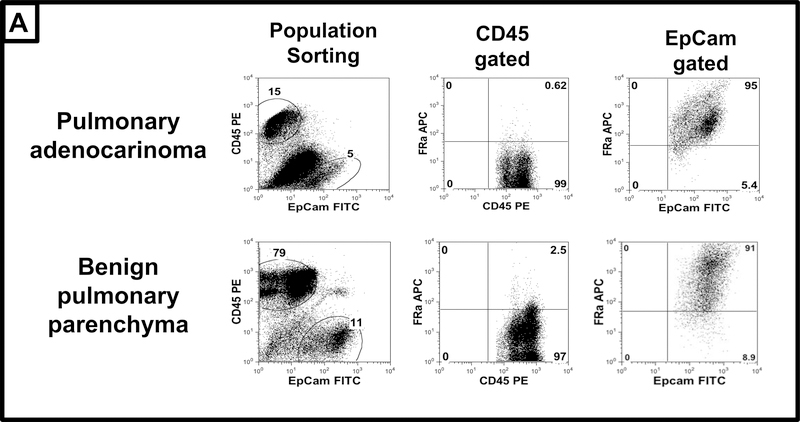

To evaluate of the specificity of EC17 to the FRα in the lung, we, began by investigating expression of the FRα in both biopsy proven pulmonary adenocarcinoma and in associated surrounding benign parenchyma. By flow cytometry, 4 of the 5 adenocarcinoma samples analyzed displayed FRα co-localization to epithelial cells with minimal co-expression of CD45 leukocytes (Figure 1). In this group, FRα was expressed on 75±18% (range 51–99%) of EPCAM tumor cells versus 24±8% of leukocytes. In the remaining tumor sample, FRα was observed on less than 10% on EPCAM+ tumor cells and 17% on parenchyma (data not shown). Upon analysis of the 5 normal lung parenchyma samples, FRα co-localized to EPCAM cells in 100% of samples. FRα was expressed in 84±14% (range 65—95%) of EPCAM+ epithelial cells and 15±6% of leukocytes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: FRα Expression in pulmonary adenocarcinoma and normal lung parenchyma.

Tumor and surrounding benign tissue were obtained from 5 patients undergoing resection of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Samples were stained with surface markers (EPCAM-FITC, CD45-PE, and FRα-APC), then analyzed using flow cytometry. Representative tracings are provided. In tumors (top panels) nearly 85% of epithelial cells express the FRα, in contrast to low levels on leukocytes. In benign lung tissue (lower panels), epithelial cell similarly express high levels of FRα, while low levels of FRα are observed on leukocytes.

This data concurs with prior literature suggesting that approximately 85% of pulmonary adenocarcinomas have high levels of FRα expression (p=0.76). However, because the proportion of epithelial cells expressing FRα are similar within malignant and benign pulmonary tissue (p=0.54), further histologic evaluation was necessary to better understand differences in FRα density.

FRα density is elevated in pulmonary adenocarcinoma

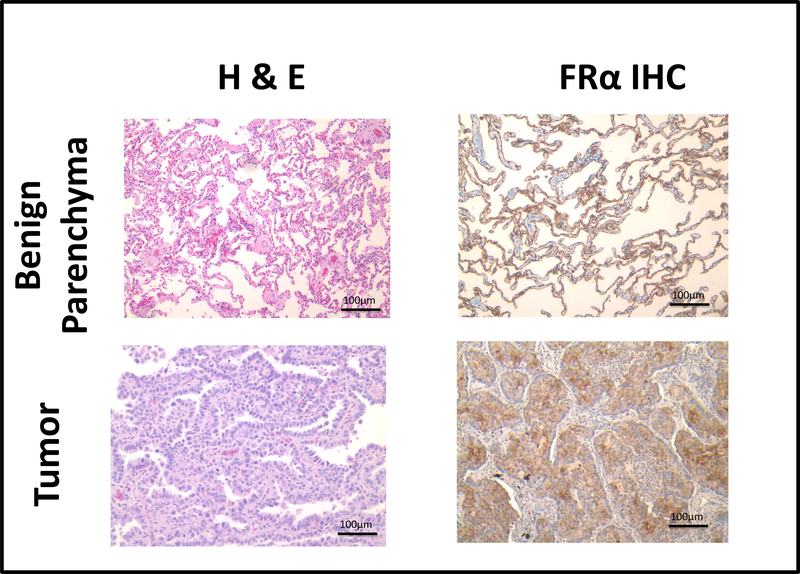

Because the proportion of pulmonary adenocarcinoma and normal lung parenchyma cells expressing FRα are similar, we next sought to determine if there were differences in the FRα density among these tissues. To do this, we performed immunohistochemistry on paraffin fixed tumor samples of lung adenocarcinomas and the normal peritumoral tissue.

We observed avid staining for FRα within 4 of the 5 lung adenocarcinoma samples (Table 1, Figure 2). In contrast, weak homogenous staining was appreciated on pneumocytes from all five normal lung tissue samples (p=0.009) (Table 1, Figure 2). These data suggested that the density of FRα is elevated in pulmonary adenocarcinomas as compared to benign tissue. This differential in FRα density suggests that the FRα-targeted IMI agent, EC17, would concentrate in pulmonary adenocarcinoma as compared to benign parenchyma.

Table 1:

FRα staining of pulmonary adenocarcinomas and benign parenchyma in 5 human subjects

| Malignant Tissue (n=5) | Benign Parenchyma (n=5) | |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated FRα Staining | 4 | 0 |

| Low/Normal FRα Staining | 1 | 5 |

Figure 2: Histologic and Immunohistological Assessment of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma and Benign Lung Parenchyma.

Specimen from 5 patients undergoing resection for pulmonary adenocarcinoma were obtained and prepared for standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and FRα immnohistochemical (IHC) staining. Representative benign parenchyma (top panels) and tumor (bottom panels) sample are depicted. Both benign and malignant pulmonary epithelial cells express the FRα; however, there is a greater density of the FRα in the malignant state.

Benign thoracic tissues autofluorescence in the visible spectrum

After establishing the potential of EC17 to minimize background, we focused on the issue of autofluorescence. As previously noted, the FITC fluorophore of EC17 is a visible wavelength fluorophore that has an excitation and emission wavelength of 490nm and 521nm, respectively. Many human tissues are known to be naturally fluorescent in the visible spectrum (400–700nm) [27]. If not properly controlled for, autofluorescence in this range can reduce the value of IMI techniques utilizing EC17.

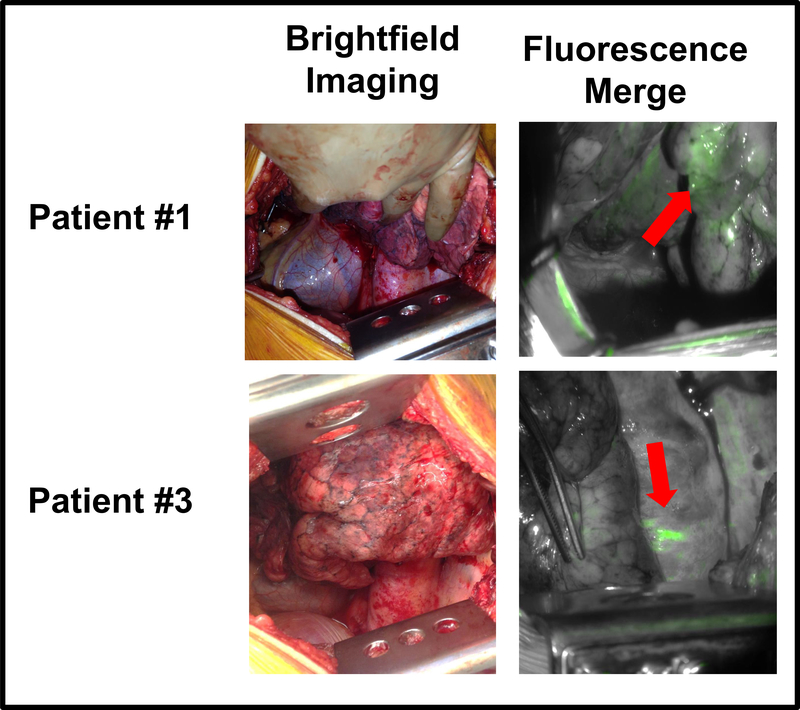

To address this concern, we sought to first characterize background tissue autofluorescence in the human thorax. Five patients undergoing resection for pulmonary adenocarcinoma underwent fluorescent imaging at the time of thoracotomy (no contrast agent was administered). To replicate light source and detection settings required when using EC17, thoracic tissues were excited using a wavelength of 490nm and fluorescent signal was detected using a filter selecting for light of 521nm. In vivo, the chest demonstrated autofluorescence at a wavelength the standard light exposure settings of a typical video camera (20 milliseconds) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Human Thorax is Naturally Autofluorescent.

In 5 patients, brightfield (normal operating room lights) images and fused images were obtained in the absence of a IMI agent. For fused images, tissue was exposed to light of 490nm, and fluorescent signal of 521nm was detected. As can be observed in the representative patient images, fluorescent signal is emitted from multiple areas within the chest.

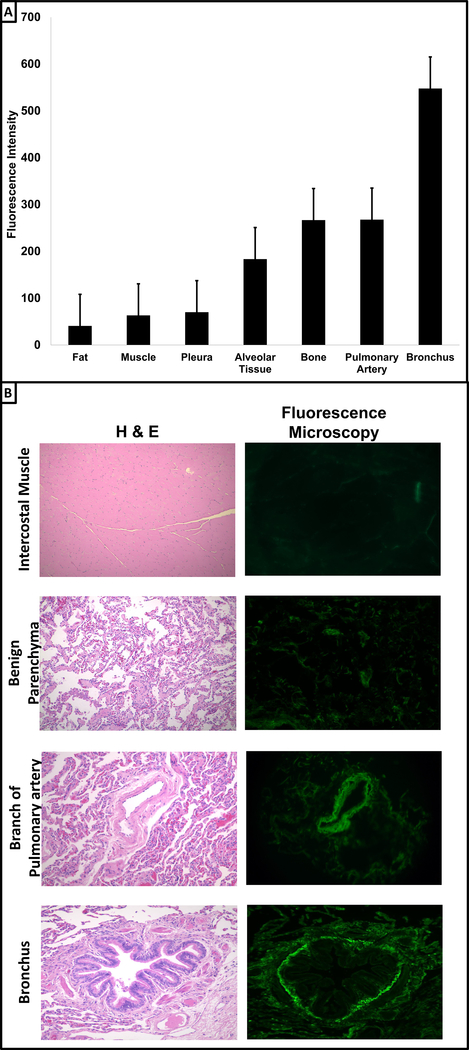

To more precisely identify tissues responsible for observed autofluorescence at 521nm, the previously described specimens were imaged ex vivo. After exposure to light at a wavelength of 490nm, fluorescent signals at 521m were quantified for mediastinal fat, intercostal muscles, visceral pleural surface, pulmonary parenchyma, bone (rib), the lobar pulmonary artery, and the lobar bronchus (Figure 4a). Autofluorescence ranged from 50 to higher levels 550 in this contrast naïve state. The highest fluorescent signals were observed at the bronchial stump (547±98, range 423—699), followed by the pulmonary artery (267±64, range 200—374), and cortical bone (266±17, range 243—287). Moderate levels of autofluorescence were appreciated after imaging lung parenchyma (183±49, range 136—257). The remaining analyzed tissues had relatively low natural fluorescence: muscle (63±6, range 53—70), visceral pleura (70±7, range 60—80) and fat (41±7, range 30—47) (Figure 4a). To confirm ex vivo findings, autofluorescence of various tissues (intercostal muscle, benign parenchyma, pulmonary artery, and bronchus) was assessed using fluorescence microscopy (Figure 4b). As observed ex vivo, after exposure to a light source of 490nm, we appreciated relative low levels of autofluorescence in the muscle and benign pulmonary tissue and elevated levels in both bronchial and arterial samples.

Figure 4: Autofluorescence of Benign Tissues in the Human Thorax.

Panel A: Specimen from 5 patients undergoing resection for pulmonary adenocarcinoma were obtained and imaged ex vivo. For each patient, pericardial fat, intercostal muscle, visceral pleura, benign tissue, rib, pulmonary artery branch and bronchus were exposed to light at a wavelength of 490nm. Autofluorescence at 521nm was recorded. Data is plotted as mean with standard error bars. Panel B: In order to confirm ex vivo results, portions of the intercostal muscle, benign parenchyma, pulmonary artery, and bronchus were obtained and sectioned at 10μM. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (first column). Next, using an Olympus IX51 fluorescent microscope, unstained tissues were exposed to 490nm and detected using fluorescein specific filter set.

Taken together, these data confirmed that the human thorax produces visible wavelength autofluorescence (521nm) when exposed to 490nm light.

Fluorescence image capture properties can be optimized to minimize autofluorescence and enhance IMI with EC17

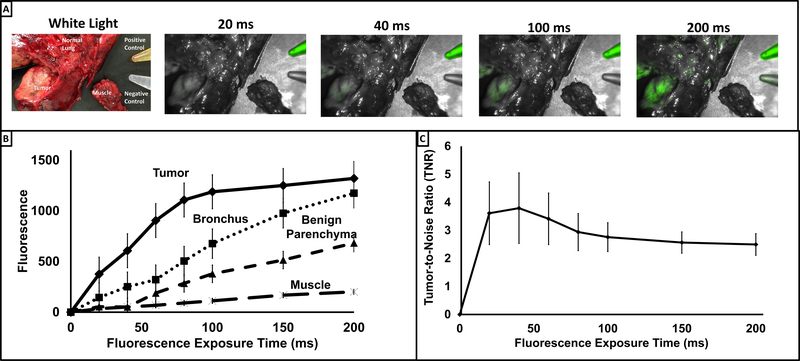

After quantifying thoracic autofluorescence in a tracer-free setting, we next examined the chest after administration of EC17. Briefly, five patients with biopsy proven lung adenocarcinoma were administered a systemic dose of 0.1mg/kg EC17 two hours prior to tumor resection. Resected pulmonary specimen and intercostal muscle (negative control) were imaged ex vivo at various fluorescence exposure times (0 to 200 milliseconds (ms) at 20 ms increments). As seen in Figure 5a, as exposure time increased, EC17-generated tumor fluorescence qualitatively increased. As predicted, autofluorescence of the bronchus, lung parenchyma and muscle also increased with exposure time (Figure 5b).

Figure 5: Fluorescent signal alterations as a function of exposure time.

Panel A: Specimen were obtained from 5 patients who had received 0.1mg/kg two to four hours prior to resection. Specimen were exposed to wavelength of 490nm from 20ms to 200ms. Fluorescence at 521nm was recorded. Pictured is a representative sample. Panel B: Fluorescent signal of tumor, bronchus, benign pulmonary parenchyma, and intercostal muscle were plotted vs exposure time. Plots depict mean fluorescence at 521nm from the 5 patients. Panel C: Tumor-to-Noise Ratio (TNR) was calculated at various exposure times. Values for TNR were generated using the following formula: Tumor fluorescence/[(bronchus fluorescence + benign parenchyma fluorescence + muscle fluorescence)/3].

To determine the exposure time which maximized tumor specific fluorescence relative to noise (background/autofluorescence) of benign tissue, images of each specimen were obtained at variable exposure times and region of interest (ROI) software was used to determine an objective tumor-to-noise ratio (TNR) (Figure 5c).

TNRs across exposure times ranged from 2.49 (200ms) to 3.79 (40ms); with a peak TNR (3.79 ± 2.5) at a fluorescence exposure time of 40ms (Figure 5c). At greater exposure times, the TNR trended downwards but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.453).

Together, these experiments demonstrated that EC17 based IMI can be used intraoperatively to detect lung cancers. Secondly, though high levels autofluorescence are noted in the human thorax, TNR can be improved by modifying the exposure time on imaging capture equipment.

Discussion:

The data described in this report provides the background for additional studies involving folate-targeted intraoperative molecular imaging using EC17. Here we provide preliminary evidence demonstrating that lung adenocarcinomas have an elevated density of the FRα as compared to benign pulmonary parenchyma. After identifying autofluorescence in the human thorax, we demonstrate that this hurdle can be overcome by modifying fluorescent exposure time. In this system, the optimal exposure time was found to be 40ms.

Previous attempts involving IMI have been overall successful, but have been limited by uptake of contrast agent in a non-specific manner thus creating background signal [13, 28]. Coupling a fluorescent fluorophore to a targeted molecule has the potential to increase specificity and limit background. In this particular study, the FRα was targeted. The FRα is an attractive target for intraoperative cancer imaging for the NSCLC patient. In non-malignant states the FRα is not expressed at the luminal surface of polarized epithelial cells, thus it does not have access to serum folate [28–30]. However, FRα is also expressed at high levels (1–3 million receptors/cancer cell) on a number of solid cancers, including NSCLC, which provides an avid binding site for serum folate [16, 18, 31]. As such, FRα provides a selective molecular target on cancers for diagnostic purposes. A similar approach has already been demonstrated for ovarian and breast cancers [20].

In this study, we exploited the variable FRα densities in NSCLC tumors and utilized the fluorescent agent, EC17, which consists of the folate molecule covalently linked to the fluorescein fluorophore. FITC is a well-characterized and safe fluorescent imaging agent. Further, FITC’s high quantum yield and relative photostability make it a reliable, accurate, long-lasting tracer for target labeling [32]. Though FITC has been used primarily for microscopic applications, we demonstrate FITC’s high fluorescence which allows for aggregation adequate signal for identifying tumors using with relative ease. This provides additional data suggesting that macroscopic fluorescence imaging with FITC is a viable option.

As demonstrated both in this study and previous studies, autofluorescence in the human thorax is a potential limitation to fluorescence imaging in the wavelength of FITC. Biological chromophores such as elastins and collagens have broad excitation and emission wavelengths that overlap the wavelengths of fluorescein and make discrimination difficult [33]. Fortunately, the quantum yield of fluorescein and overall aggregation of contrast agent in tumors allowed us to still discriminate benign and malignant tissue. Furthermore, we provide data demonstrating that discrimination can be further enhanced by manipulating fluorescence exposure times. As noted from the results of our pilot study, 40ms appears to be the optimal exposure time and allows for maximum malignant tissue discrimination. Of note, in addition to altering exposure time, we unsuccessfully attempted to account for autofluorescence by altering our excitation light wavelength and intensity, modifying filter-systems (using long pass and notched filter approaches), and minimizing ambient light.

From a safety standpoint, we did observe one patient in our study who developed a mild hypersensitivity reaction which was controlled with a one-time dose of intravenous diphenhydramine. This was a transient episode with no serious or permanent sequela.

Although encouraging, we understand the limitations of this study. As noted, flow cytometry data confirms that the percentage of lung adenocarcinomas displaying FRα positivity is variable. Although a small cohort, we found 80% of pulmonary adenocarcinoma specimen with high FRα, which is in accordance to other published work suggesting that approximately 85% of NSCLC tumors are high expressers for the FRα [28–29]. Although not encountered in this study, we anticipate that tumors located near or on highly naturally autofluorescent tissue such as vascular on bronchial margins would be detect using EC17. Lastly, although not a dramatic barrier, we required patients to discontinue folate containing vitamins before their imaging. Though this is a minor inconvenience it does allude to the potential for high folate diets to hinder this imaging technique.

In the future, we plan to use this work as a proof-of-principle to further the use of IMI using EC17. New near-infrared folate contrast agents are being developed [34], as well as other targeted near-infrared agents [35]. These agents will be less hindered by autofluorescence in the human thorax and also allow excellent depth of tissue penetration. Regardless, optical agents within the NIR spectral range will require a set of optimization criteria similar to what we describe for EC17. With standardization of image acquisition, intraoperative molecular imaging will open a wide array of opportunities that can aide the oncologic surgeon in localizing malignancies in the thorax.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: JDP was supported by a grant by the American Philosophical Society, and an NIH F32 (1F32CA210409), and an Association for Academic Surgery Research Grant. SS was supported by a federal funding including an NIH R01 (CA193556).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: PL is on the Board of Directors for OnTarget Laboratories, manufacturers of EC17.

References:

- 1.2013 United States Procedure Volumes Database (2013). Reuters Thomas, Ed. Reuters T United States. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Inpatient Sample (NIS). (2011). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp., Ed. Quality AfHRa.

- 3.Aliperti LA, Predina JD, Vachani A, Singhal S (2011) Local and systemic recurrence is the Achilles heel of cancer surgery. Annals of surgical oncology 18:603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedor D, Johnson WR, Singhal S (2013) Local recurrence following lung cancer surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Surgical oncology 22:156–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelsey CR, Marks LB, Hollis D, et al. (2009) Local recurrence after surgery for early stage lung cancer: an 11-year experience with 975 patients. Cancer 115:5218–5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimura H, Nichols FC, Yang P, et al. (2007) Survival after recurrent nonsmall-cell lung cancer after complete pulmonary resection. Ann Thorac Surg 83:409–417; discussioin 417–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okusanya OT, Madajewski B, Segal E, et al. (2013) Small Portable Interchangeable Imager of Fluorescence for Fluorescence Guided Surgery and Research. Technology in cancer research & treatment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madajewski B, Judy BF, Mouchli A, et al. (2012) Intraoperative near-infrared imaging of surgical wounds after tumor resections can detect residual disease. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 18:5741–5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dam GM, Themelis G, Crane LM, et al. (2011) Intraoperative tumor-specific fluorescence imaging in ovarian cancer by folate receptor-alpha targeting: first in-human results. Nature medicine 17:1315–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Vorst JR, Schaafsma BE, Hutteman M, et al. (2013) Near-infrared fluorescence-guided resection of colorectal liver metastases. Cancer 119:3411–3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang JX, Keating JJ, Jesus EM, et al. (2015) Optimization of the enhanced permeability and retention effect for near-infrared imaging of solid tumors with indocyanine green. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 5:390–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okusanya OT, DeJesus EM, Jiang JX, et al. (2015) Intraoperative molecular imaging can identify lung adenocarcinomas during pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 150:28–35 e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt D, Okusanya O, Judy R, et al. (2014) Intraoperative near-infrared imaging can distinguish cancer from normal tissue but not inflammation. PLoS One 9:e103342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thiberville L, Moreno-Swirc S, Vercauteren T, Peltier E, Cave C, Bourg Heckly G (2007) In vivo imaging of the bronchial wall microstructure using fibered confocal fluorescence microscopy. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 175:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiberville L, Salaun M, Lachkar S, et al. (2009) Human in vivo fluorescence microimaging of the alveolar ducts and sacs during bronchoscopy. The European respiratory journal 33:974–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low PS, Kularatne SA (2009) Folate-targeted therapeutic and imaging agents for cancer. Current opinion in chemical biology 13:256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker N, Turk MJ, Westrick E, Lewis JD, Low PS, Leamon CP (2005) Folate receptor expression in carcinomas and normal tissues determined by a quantitative radioligand binding assay. Analytical biochemistry 338:284–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Shannessy DJ, Yu G, Smale R, et al. (2012) Folate receptor alpha expression in lung cancer: diagnostic and prognostic significance. Oncotarget 3:414–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantovani LT, Miotti S, Menard S, et al. (1994) Folate binding protein distribution in normal tissues and biological fluids from ovarian carcinoma patients as detected by the monoclonal antibodies MOv18 and MOv19. European journal of cancer 30A:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tummers QR, Hoogstins CE, Gaarenstroom KN, et al. (2016) Intraoperative imaging of folate receptor alpha positive ovarian and breast cancer using the tumor specific agent EC17. Oncotarget. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzzo TJ, Jiang J, Keating J, et al. (2016) Intraoperative Molecular Diagnostic Imaging Can Identify Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Urol 195:748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Jesus E, Keating JJ, Kularatne SA, et al. (2015) Comparison of Folate Receptor Targeted Optical Contrast Agents for Intraoperative Molecular Imaging. Int J Mol Imaging 2015:469047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judy RP, Keating JJ, DeJesus EM, et al. (2015) Quantification of tumor fluorescence during intraoperative optical cancer imaging. Sci Rep 5:16208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okusanya OT, Madajewski B, Segal E, et al. (2015) Small portable interchangeable imager of fluorescence for fluorescence guided surgery and research. Technology in cancer research & treatment 14:213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Judy BF, Aliperti LA, Predina JD, et al. (2012) Vascular endothelial-targeted therapy combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy induces inflammatory intratumoral infiltrates and inhibits tumor relapses after surgery. Neoplasia 14:352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eruslanov E, Daurkin I, Ortiz J, Vieweg J, Kusmartsev S (2010) Pivotal Advance: Tumor-mediated induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and M2-polarized macrophages by altering intracellular PGE(2) catabolism in myeloid cells. J Leukoc Biol 88:839–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Weissleder R, Tung CH (2002) Novel near-infrared cyanine fluorochromes: synthesis, properties, and bioconjugation. Bioconjug Chem 13:605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Low PS, Antony AC (2004) Folate receptor-targeted drugs for cancer and inflammatory diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 56:1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Low PS, Henne WA, Doorneweerd DD (2008) Discovery and development of folic-acid-based receptor targeting for imaging and therapy of cancer and inflammatory diseases. Acc Chem Res 41:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia W, Low PS (2010) Folate-targeted therapies for cancer. J Med Chem 53:6811–6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu Y, Sega E, Leamon CP, Low PS (2004) Folate receptor-targeted immunotherapy of cancer: mechanism and therapeutic potential. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 56:1161–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sjoback R, Nygren J, Kubista M (1995) Absorption and Fluorescence Properties of Fluorescein. Spectrochim Acta A 51:L7–L21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monici M (2005) Cell and tissue autofluorescence research and diagnostic applications. Biotechnology annual review 11:227–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy GT, Okusanya OT, Keating JJ, et al. (2015) The Optical Biopsy: A Novel Technique for Rapid Intraoperative Diagnosis of Primary Pulmonary Adenocarcinomas. Ann Surg 262:602–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Boer E, Warram JM, Tucker MD, et al. (2015) In Vivo Fluorescence Immunohistochemistry: Localization of Fluorescently Labeled Cetuximab in Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Sci Rep 5:10169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]