N-Acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA) is one of the key enzymes involved in the degradation of fatty acid ethanolamides (FAEs), especially for palmitoylethanolamide (PEA).

N-Acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA) is one of the key enzymes involved in the degradation of fatty acid ethanolamides (FAEs), especially for palmitoylethanolamide (PEA).

Abstract

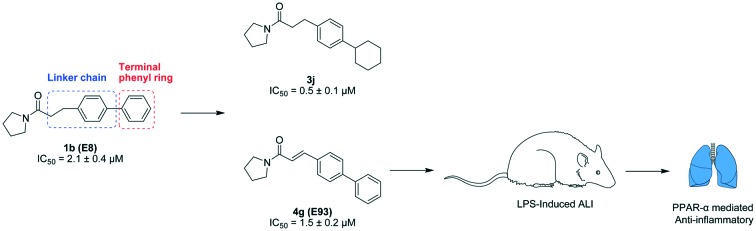

N-Acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA) is one of the key enzymes involved in the degradation of fatty acid ethanolamides (FAEs), especially for palmitoylethanolamide (PEA). Pharmacological blockage of NAAA restores PEA levels, providing therapeutic benefits in the management of inflammation and pain. In the current work, we showed the structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies for pyrrolidine amide derivatives as NAAA inhibitors. A series of aromatic replacements or substituents for the terminal phenyl group of pyrrolidine amides were examined. SAR data showed that small lipophilic 3-phenyl substituents were preferable for optimal potency. The conformationally flexible linkers increased the inhibitory potency of pyrrolidine amide derivatives but reduced their selectivity toward fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH). The conformationally restricted linkers did not enhance the inhibitor potency toward NAAA but improved the selectivity over FAAH. Several low micromolar potent NAAA inhibitors were developed, including 4g bearing a rigid 4-phenylcinnamoyl group. Dialysis and kinetic analysis suggested that 4g inhibited NAAA via a competitive and reversible mechanism. Furthermore, 4g showed high anti-inflammatory activities in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced acute lung injury (ALI) model, and this effect was blocked by pre-treatment with the PPAR-α antagonist MK886. We anticipate that 4g (E93) will enable a new agent to treat inflammation and related diseases.

1. Introduction

N-Acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA) is a cysteine hydrolase that belongs to the choloylglycine hydrolase family.1–3 It is one of the key enzymes in the degradation of fatty acid ethanolamides (FAEs), especially for palmitoylethanolamide (PEA).4 PEA is involved in various physiological processes including regulation of pain and inflammation through the activation of nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPAR-α).5–7 In experimental models of acute lung injury (ALI) and rheumatoid arthritis, PEA metabolism is disturbed and a decrease in PEA levels is found in inflammation tissues.8,9 Pharmacological blockage of NAAA elevates the PEA levels and exerts excellent anti-inflammatory activities in these models.8,9 Similarly, in the models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain, inhibition of NAAA activity increases the levels of PEA and reduces inflammation and hyperalgesia in animals.10–12 Furthermore, undesirable cardiovascular effects and gastrointestinal hemorrhage, commonly seen in experimental animals treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are not observed for NAAA inhibition.13 An NAAA inhibitor, therefore, has been proposed as a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of pain, inflammation and other related diseases.14,15

Despite the therapeutic potential of NAAA inhibition in various diseases, only a few structural classes of NAAA inhibitors have been identified. Recently, two classes of NAAA inhibitors have been disclosed.15 One class is the covalent NAAA inhibitors, which contain reactive chemical warheads, such as β-lactone/β-lactam, isothiocyanate and oxazolidone imide.16–19 These electrophilic chemical groups can covalently react with the cysteine nucleophile of NAAA.19–21 However, inhibitors with such structures show poor biostability, thus limiting their systemic effect. For example, β-lactone-based inhibitors can be quickly hydrolysed to the corresponding β-hydroxy acid in physiological pH buffer or rat plasma.22 Furthermore, some inhibitors with reactive groups tend to be nonselective toward off-target lipid hydrolases, such as fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and acid ceramidase (AC), and may lead to unwanted side effects.23,24 Other types of inhibitors that non-covalently react with NAAA include benzothiazole–piperazine, retroamide derivatives of palmitamine and pyrrolidine amide derivatives.25–27 These non-covalent inhibitors are not only potent and selective for NAAA versus other lipid hydrolases, but many are stable in rat plasma and in vivo.27

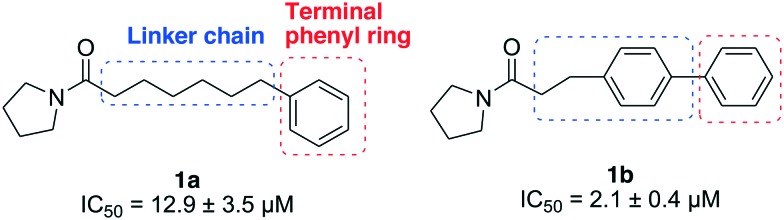

Previously, we described a structure–activity relationship (SAR) study targeting the pyrrolidine group and the palmitoyl chain of palmitoylpyrrolidine, and disclosed two micromolar potent NAAA inhibitors 1a and 1b with an optimized linker length.27 In the present study, we further modified the linker chain and terminal phenyl group of 1a and 1b to obtain more potent and selective NAAA inhibitors (Fig. 1). We explored the sizes, shapes and lipophilic requirements of the terminal phenyl ring and linker chain for potent NAAA inhibition, and also evaluated the selectivity, stability and inhibition mechanism of the best among these novel compounds. Several potent NAAA inhibitors, including 3j, 4a and 4g, were identified. One of the most potent inhibitors, 4g, showed PPAR-α mediated anti-inflammatory activity in the LPS induced ALI model and may enable a new agent for the treatment of inflammation related diseases.

Fig. 1. Structures of NAAA inhibitors 1a and 1b.

2. Chemistry

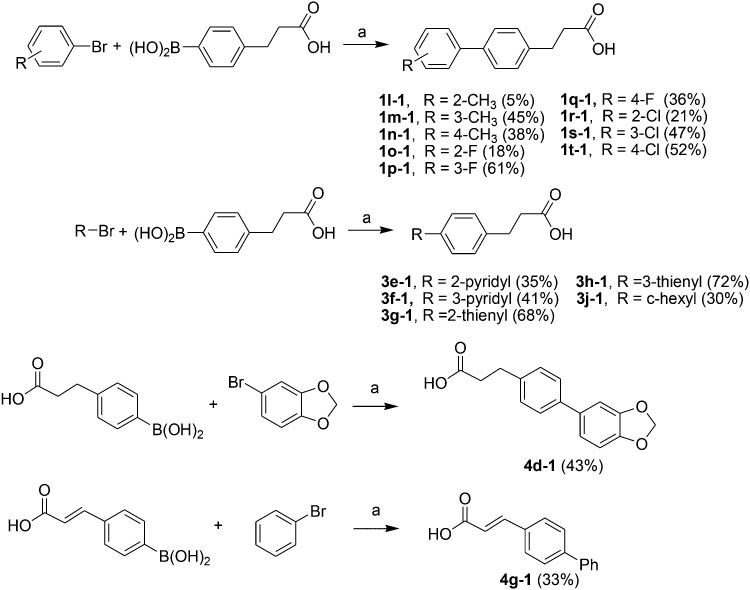

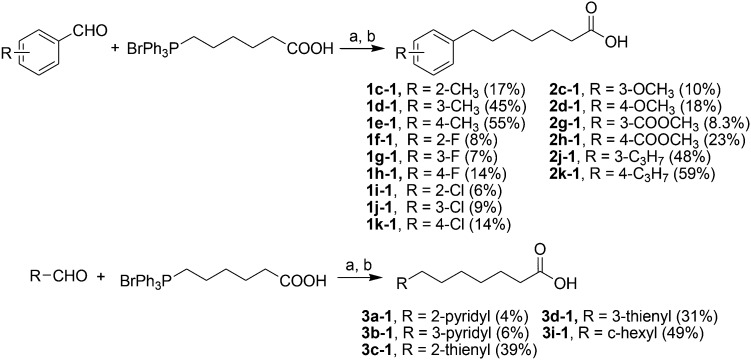

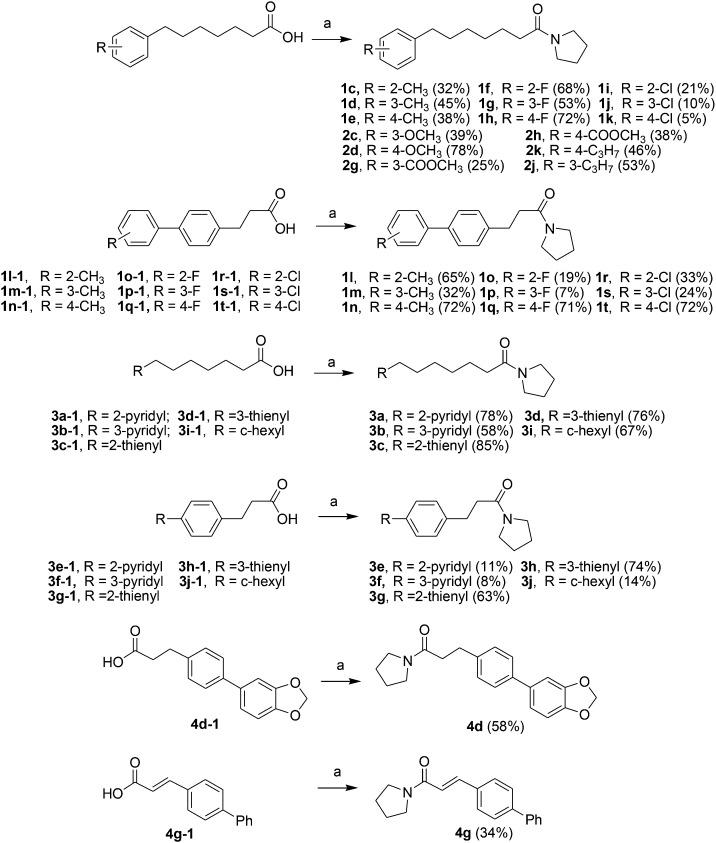

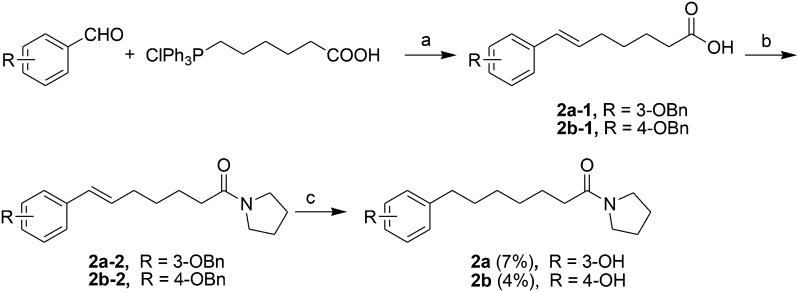

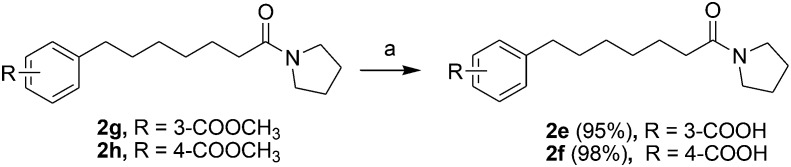

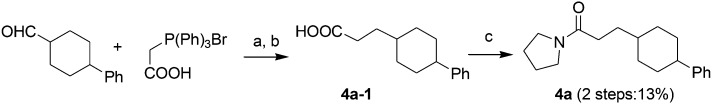

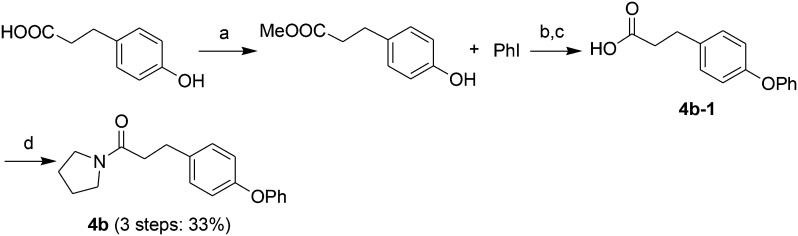

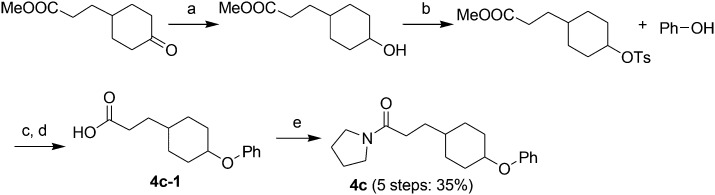

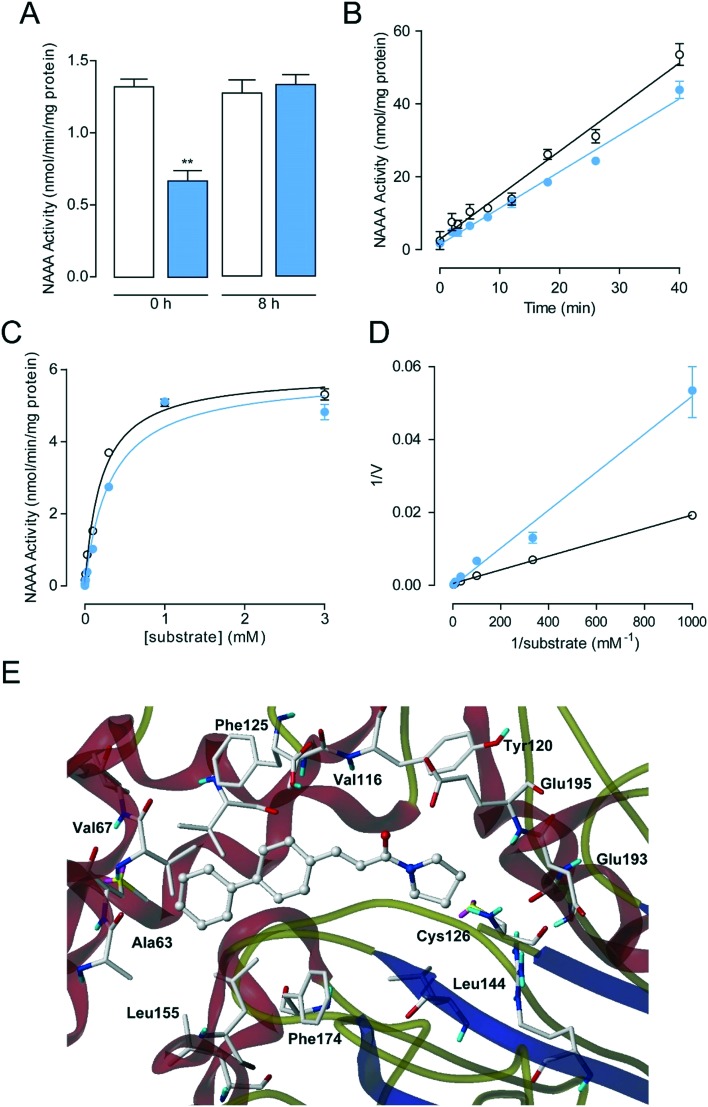

Acids 1l-1–1t-1, 3e-1–3j-1, 4d-1 and 4g-1 were synthesized by Suzuki coupling of 3-(4-boronophenyl) propanoic acid and an aryl halide (Scheme 1).28 The synthesis of commercially unavailable acids 1c-1–1k-1, 2c-1, 2d-1, 2g-1–2j-1, 3a-1–3d-1, and 3i-1 were performed by catalytic hydrogenation of their respective intermediates, prepared by the reaction of phosphonium salt and the corresponding aldehyde in the presence of lithium hexamethyldisilazane (LHMDS) (Scheme 2).19 Pyrrolidine amides 1c–1t, 2c, 2d, 2g–2j, 3a–3j, 4d and 4g were synthesized by the reaction of pyrrolidine with the appropriate acids, in the presence of 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) and triethylamine (Et3N) (Scheme 3).27 Amides 2a and 2b were prepared by catalytic hydrogenation of their respective intermediates, obtained by the reaction of 2a-1 and 2b-1 with pyrrolidine by the EDC method. Acids 2a-1 and 2b-1 were synthesized by the Wittig reaction of phosphonium salt and the corresponding aldehyde (Scheme 4).19 Subsequent treatment of 2g and 2h with lithium hydroxide (LiOH) afforded 2e and 2f (Scheme 5).19 Pyrrolidine amide 4a was prepared by the reaction of the appropriate acid 4a-1 with pyrrolidine.27 Acid 4a-1 was obtained from the corresponding aldehydes via Wittig olefination with phosphonium salt, followed by a one-pot catalytic hydrogenation reaction (Scheme 6).19 The preparation of 4b involved coupling of acid 4b-1 with pyrrolidine. Carboxylic acid 4b-1 was obtained by the reaction of ethyl 4-hydroxyhydrocinnamate with iodobenzene and subsequent hydrolysis of ester (Scheme 7).19 Pyrrolidine amide 4c was prepared by the reaction of the appropriate acid 4c-1 with pyrrolidine. Acid 4c-1 was obtained from the reaction of phenol with O-protected intermediates, obtained by the reduction of methyl 3-(4-oxocyclohexyl)propanoate with NaBH4 followed by reaction with tosyl chloride (TsCl) (Scheme 8).13 Compound 4f was synthesized by the amide coupling reaction of acid 4f-1 and pyrrolidine. Amide 4e was obtained by the one-pot catalytic hydrogenation reaction of 4f (Scheme 9).19

Scheme 1. The synthesis of compounds 1l-1–1t-1, 3e-1–3j-1, 4d-1 and 4g-1. Reagents and conditions: (a) Na2CO3, Pd(PPh3)4, toluene/EtOH/H2O, 80 °C, 2 h.

Scheme 2. The synthesis of compounds 1c-1–1k-1, 2c-1, 2d-1, 2g-1–2j-1, 3a-1–3d-1, and 3i-1. Reagents and conditions: (a) LHMDS, THF, –78–0 °C; (b) H2, Pd/C, room temperature, 2 h.

Scheme 3. The synthesis of compounds 1c–1t, 2c, 2d, 2g–2j, 3a–3j, 4d and 4g. Reagents and conditions: (a) EDCI, pyrrolidine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 4 h.

Scheme 4. The synthesis of compounds 2a and 2b. Reagents and conditions: (a) LHMDS, THF, –78 °C-room temperature; (b) EDCI, pyrrolidine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 2–4 h; (c) H2, Pd/C, room temperature, 2 h.

Scheme 5. The synthesis of compounds 2e and 2f. Reagents and conditions: (a) LiOH, EtOH/H2O, 0 °C-room temperature, 4 h.

Scheme 6. The synthesis of compound 4a. Reagents and conditions: (a) LHMDS, THF, –78 °C-room temperature; (b) H2, Pd/C, room temperature, 2 h; (c) EDCI, pyrrolidine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 4 h.

Scheme 7. The synthesis of compound 4b. Reagents and conditions: (a) SOCl2, CH3OH, room temperature; (b) NaH, DMSO, 120 °C, 24 h; (c) NaOH, EtOH/H2O, room temperature, 2 h, then 3 N HCl; (d) EDCI, pyrrolidine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 4 h.

Scheme 8. The synthesis of compound 4c. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBH4, THF, 0 °C, 4 h; (b) TsCl, room temperature, 2 h; (c) NaH, DMSO, 120 °C, 24 h; (d) NaOH, EtOH/H2O, room temperature, 2 h, then 3 N HCl; (e) EDCI, pyrrolidine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 4 h.

Scheme 9. The synthesis of compounds 4e and 4f. Reagents and conditions: (a) EDCI, pyrrolidine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 2–4 h; (b) H2, Pd/C, room temperature, 2 h.

3. Enzyme assay

The inhibition activity of the new synthesized compounds against rat NAAA (rNAAA) and rat FAAH (rFAAH) was examined, using heptadecenoylethanolamide (C17:1 FAE) and [3H]-AEA as substrates, respectively. HEK293 cells overexpressing rat NAAA (HEK293-rNAAA)29 and rat FAAH (HEK293-rFAAH)30 were kind gifts from Dr. Daniele Piomelli of the University of California, Irvine. The NAAA/FAAH dual inhibitor carmofur (1 μM) was used as the positive control. The residual hydrolysis products of the substrates were determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).12

4. Results and discussion

4.1. SAR study

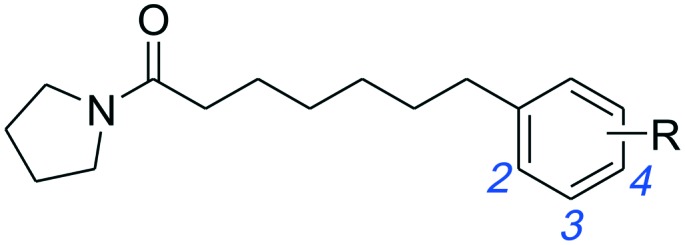

Initially, 2 series of substitutions for the terminal phenyl groups of 1a and 1b were tested (Table 1). Substitution at position 2 for 1a and 1b with -Me (1c, 1l) or -Cl (1i, 1r) significantly reduced the inhibitory potency. The only exceptions to this generalization were the -F derivatives (1f, 1o), which exhibited similar activity to unsubstituted derivatives. These observations are analogous to the SAR results of oxazolidone derivatives which indicated that position 2 of the distal phenyl ring is unsuitable for further modification.19 Compared to unsubstituted 1a, substitution at position 3 or 4 with -F (1g, 1h) or -Me (1d, 1e) afforded comparable potent inhibitors. The 3-Cl substitution (1j) was 3.5-fold more effective while the 4-Cl derivative (1k) resulted in a nearly 2.7-fold decrease in inhibitory potency. However, the conformationally restricted linker chain of 1b derivatives may limit the movements of the distal phenyl group towards the most tolerant site. Substituents -Me (1m, 1n) and -Cl (1s, 1t) were poorly tolerated in position 3 or 4 of 1b; only -F derivatives (1p, 1q) matched the activity of 1b. When combined, these results seem to suggest that the binding pocket for the terminal phenyl ring is tight and, as such, only a small lipophilic group can be tolerated in this position.

Table 1. Inhibitory effects of compounds 1a–1t on rat NAAA activities a .

| R |

|

|

||

| IC50 of NAAA (μM) | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | |||

| -H | 1a | 12.9 ± 3.5 | 1b | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| 2-CH3 | 1c | 68.4 ± 12.5 | 1l | >100 |

| 3-CH3 | 1d | 8.3 ± 2.0 | 1m | 16.5 ± 3.8 |

| 4-CH3 | 1e | 9.6 ± 2.7 | 1n | 33.2 ± 9.1 |

| 2-F | 1f | 13.7 ± 4.4 | 1o | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| 3-F | 1g | 7.3 ± 2.1 | 1p | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| 4-F | 1h | 8.0 ± 2.7 | 1q | 3.4 ± 0.6 |

| 2-Cl | 1i | >100 | 1r | >100 |

| 3-Cl | 1j | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 1s | 25.4 ± 5.3 |

| 4-Cl | 1k | 34.5 ± 7.3 | 1t | 48.6 ± 9.5 |

aData are presented as IC50 ± standard error of the mean. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Next, a series of 3- or 4-substituted 1a derivatives were further examined (Table 2). Unfortunately, most of the substituted derivatives (2a, 2c–2k) were less active than the parent compound 1a. The only exception was the polar substituent 4-OH (2b), which led to a 2-fold increase in the inhibitory potency of 1a. However, the intermediate compounds 2a-2 and 2b-2 exhibited low inhibition towards NAAA, suggesting that bulky substituents were not the preferred shape patterns for NAAA inhibition. Furthermore, although the 4-OMe derivative (2d) was 2-fold less effective than unsubstituted 1a, it was still more potent than other hydrophobic substituents (2j, 2k). These observations are in agreement with the SAR results of oxazolidone imides that incorporation of the hydroxyl-containing substituent in position 4 of the distal phenyl ring can improve the inhibitory potency.19

Table 2. Inhibitory effects of compounds 2a–2j, 2a-2 and 2b-2 on rat NAAA activities a .

| |||||

| R | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | R | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | ||

| 2a | 3-OH | >100 | 2f | 4-COOH | >100 |

| 2b | 4-OH | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 2g | 3-COOCH3 | >100 |

| 2c | 3-OCH3 | >100 | 2h | 4-COOCH3 | >100 |

| 2d | 4-OCH3 | 35.4 ± 7.6 | 2j | 3-C3H7 | >100 |

| 2e | 3-COOH | >100 | 2k | 4-C3H7 | >100 |

| |||||

| R | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | R | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | ||

| 2a-2 | 3-OBn | >100 | 2b-2 | 4-OBn | >100 |

aData are presented as IC50 ± standard error of the mean. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

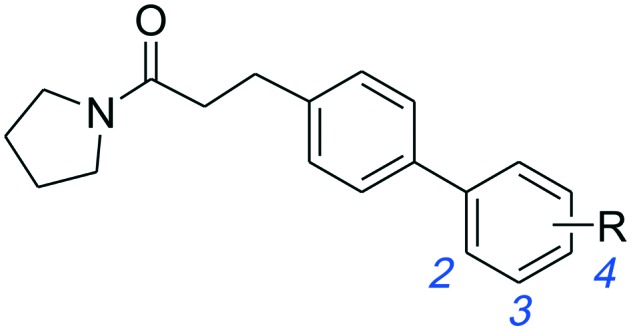

Additionally, we replaced the distal phenyl ring of 1a and 1b with isosteric aromatic groups (Table 3). In general, replacement of the phenyl group by the aromatic moiety did not significantly improve the potency. Incorporation of a more polar pyridine (3a, 3b, 3e, 3f) into the phenyl ring led to dramatic losses in potency. The pyridine derivatives are probably deprotonated under the experimental conditions (pH 4.5) and fail to effectively bind in the hydrophobic pocket of NAAA. Both 3-thiophene (3c, 3d) and 2-thiophene substituents (3h) showed similar potency compared to their corresponding phenyl derivatives, however, replacement of 1b with 2-thiophene (3g) resulted in substantial loss in binding affinity. It has been reported that the sp2 hybridized atoms cannot be well-tolerated at the end of the hydrophobic pocket of NAAA, thus replacement of the distal phenyl group with the aliphatic ring may enhance the NAAA inhibition.19,31 In agreement with previous SAR results, replacement of the distal phenyl group of 1a and 1b with the cyclohexyl ring led to progressive (3i) and substantial (3j, 3k) enhancement in potency.

Table 3. Inhibitory effects of compounds 1a–1l on rat NAAA activities a .

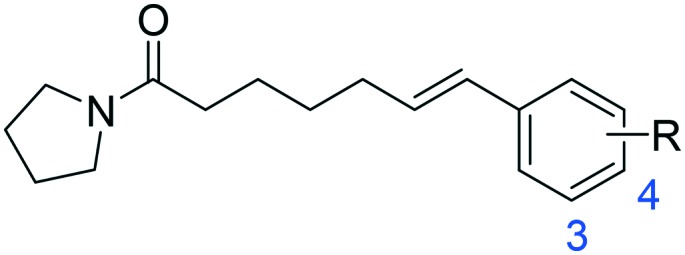

| R |

|

|

||

| IC50 of NAAA (μM) | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | |||

| -Ph | 1a | 12.9 ± 3.5 | 1b | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| 2-Pyridyl | 3a | >100 | 3e | >100 |

| 3-Pyridyl | 3b | >100 | 3f | >100 |

| 2-Thienyl | 3c | 14.1 ± 4.0 | 3g | >100 |

| 3-Thienyl | 3d | 13.2 ± 2.8 | 3h | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| c-Hexyl | 3i | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 3j | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

|

— | — | 3k | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

aData are presented as IC50 ± standard error of the mean. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

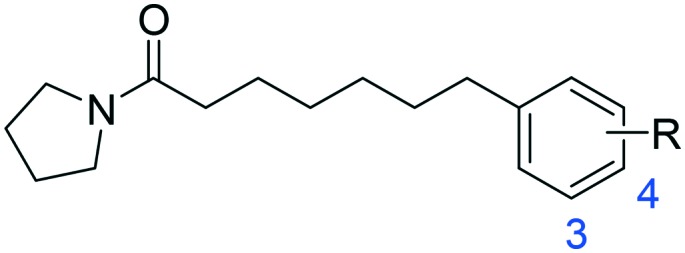

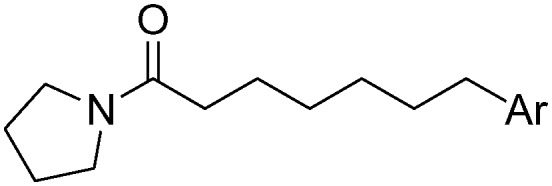

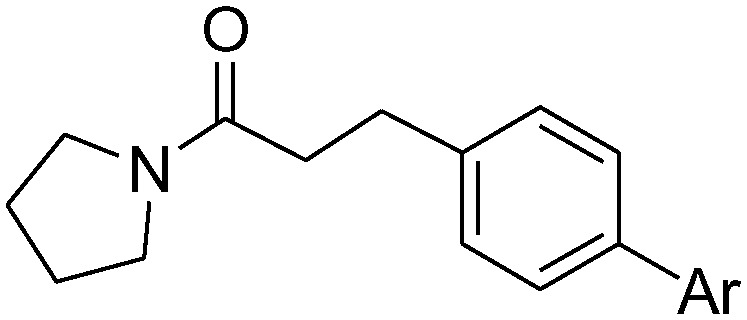

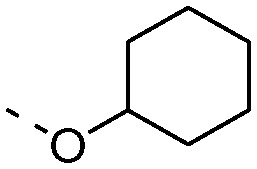

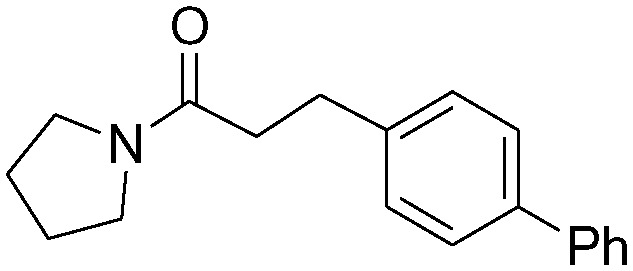

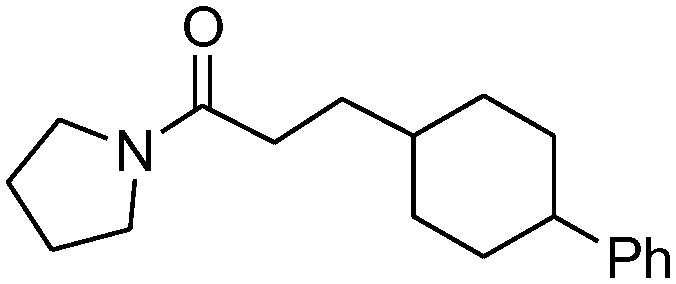

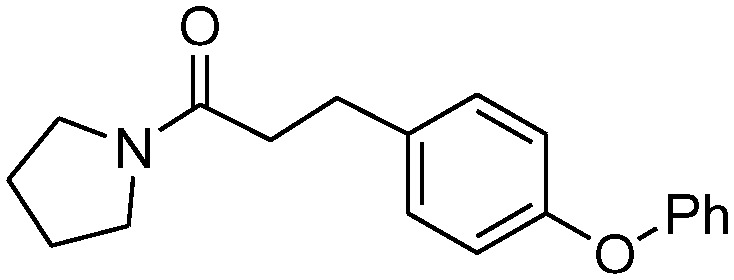

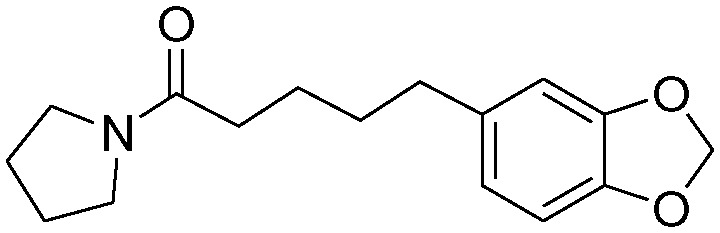

Except for the distal moieties, the linker chain of NAAA inhibitors between the 5-member heterocycle and terminal phenyl also has an important impact on the NAAA binding affinity.13,16,19 Thus, we further studied the conformational influence of the linker (Table 4). As expected, replacement of the conformationally restricted middle phenyl moiety of 1b derivatives with flexible linkers led to a progressive increase in potency. Compound 4a exhibited a 4-fold higher inhibitory activity compared to 1b, 4c was >36-fold more potent than 4b, and 4e and 4f exhibited a >20-fold increase in activity relative to the corresponding 4d. Interestingly, compound 4f is the analogue of piperine, an alkaloid found in black pepper, and shows anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects on many disease models.32 Unexpectedly, 4g bearing an unusual rigid 4-phenylcinnamoyl group showed comparable potency (IC50 = 1.5 ± 0.22 μM) with 1b. The potency of 4g may be due to the straight structures being the preferred shape for NAAA, and the 4-phenylcinnamoyl group matched the required bound conformation of the hydrophobic pocket of NAAA. However, the conformationally flexible linker was not only beneficial for NAAA inhibition but also enhanced the inhibitory potency toward another enzyme. Endocannabinoid hydrolase FAAH is a competitive target for pyrrolidine derivatives.33 The replacement of the middle phenyl moiety of 1b derivatives with the flexible linker chain also increased their inhibition potency towards FAAH (3j and 3kvs.1b, 4avs.1b, 4cvs.4b, 4e–fvs.4d) (Table 4, Table S1†). Additionally, the 4-phenylcinnamoyl group (4g) reduced FAAH inhibition 5-fold compared to 1b. Furthermore, we also tested the selectivity of pyrrolidine amide derivatives towards NAAA against AC. Acid ceramidase is a cysteine amidase that exhibits 33% amino acid identity with NAAA.2 We measured the inhibition activity of the most active compounds 3j, 3k and 4g towards rat-AC. The results showed that 3j, 3k and 4g exhibited excellent selectivity towards NAAA over AC, e.g., the selectivity of 3j against NAAA over AC is >200-fold, and all the three inhibitors reduced less than 10% of rat-AC activity at a concentration of 100 μM (Table S1†).

Table 4. Inhibitory effects of compounds 4a–4g on rat NAAA activities a .

| Structures | IC50 of NAAA (μM) | IC50 of FAAH (μM) | |

| 1b |

|

2.1 ± 0.4 | 91.5 ± 20.4 |

| 4a |

|

0.48 ± 0.11 | 66.0 ± 15.7 |

| 4b |

|

>100 | 120 ± 23 |

| 4c |

|

2.8 ± 0.5 | 45.1 ± 11.6 |

| 4d |

|

>100 | 91 ± 20 |

| 4e |

|

5.5 ± 0.8 | 42.8 ± 8.3 |

| 4f |

|

4.1 ± 1.0 | 61.3 ± 18.7 |

| 4g (E93) |

|

1.5 ± 0.22 | 550 ± 70 |

aData are presented as IC50 ± standard error of the mean. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

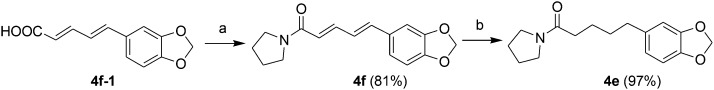

4.2. NAAA inhibition mechanism

To further understand the NAAA inhibition mechanism of these new synthesized pyrrolidine derivatives, the interaction mode of representative 4g with NAAA protein was studied, since 4g exhibits excellent selectivity towards NAAA over AC and FAAH when compared to other inhibitors, such as 3j and 3k. Complete recovery of the NAAA activity was observed by dialysis of the 4g–NAAA interaction complex after 8 hours (Fig. 2A), and rapid dilution also showed that treatment with 4g did not affect the NAAA activity after dilution, suggesting that 4g inhibited NAAA via a reversible mechanism. Furthermore, kinetic analysis revealed that 4g did not induce changes in the maximal catalytic velocity (Vmax) of NAAA (Vmax in nmol per min per mg protein, vehicle: 5.89 ± 0.12; 4g, 5 μM: 5.88 ± 0.23) but affected the Michaelis–Menten constant Km (Km in μM, vehicle: 207 ± 16; 4g, 5 μM: 322 ± 45) (Fig. 2C and D), indicating a competitive inhibition mechanism. When combined, these data suggested that 4g is a reversible and competitive NAAA inhibitor.

Fig. 2. Characterization of 4g as a reversible and competitive NAAA inhibitor. (A) NAAA activity in the presence of vehicle (open columns) or 4g (closed columns) before and 8 h after dialysis. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle, n = 8; (B) rapid dilution assay of NAAA in the presence of vehicle (open circles), 4g (closed circles); (C) Michaelis–Menten analysis of the NAAA reaction in the presence of vehicle (1% DMSO, open circles) and 4g (5 μM, closed circles). (D) The Lineweaver–Burk plot of 4g showed competitive inhibition. (E) A computational model illustrating the docking of 4g at the active site of NAAA.

Recently, Alexei Gorelik et al. have reported the crystal structure of NAAA covalently bound to ARN726 (PDB ID: ; 6DY2), which allows us to study the interaction between NAAA and 4g.21 Docking studies showed that 4g lies in the same binding pocket defined by ARN726. Briefly, the pyrrolidine ring of 4g occupies the enzyme catalytic center of NAAA, preventing the carbonyl group from forming a covalent bond with catalytic residues, e.g., Cys126. The biphenyl scaffold of 4g may be placed into the hydrocarbon tail binding pocket and forms van der Waals interactions with NAAA. The failure of hydrogen bond formation between the NAAA active site and the carbonyl group of 4g, a featured moiety of covalent inhibitors, suggested that 4g may inhibit NAAA via a reversible and competitive inhibition mechanism.

4.3. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity of 4g

We further evaluated the stability of 4g under various chemical and biological conditions (Table 5). Results indicated that 4g has excellent stability with half-lives (t1/2) > 16 h in pH 5.0 (pH for the in vitro rat NAAA inhibitory assay), pH 7.4 (physiological pH) and 80% rat plasma under 37 °C physiological conditions. These data suggested that 4g may be an ideal candidate for further in vivo studies.

Table 5. Degradation of 4g after incubation with buffers at pH 5.0, 7.4 or 80% (v/v) rat plasma.

| Inhibitor |

t

1/2 (h) |

||

| pH 5.0 | pH 8.0 | 80% rat plasma | |

| 4g | >16 h | >16 h | >16 h |

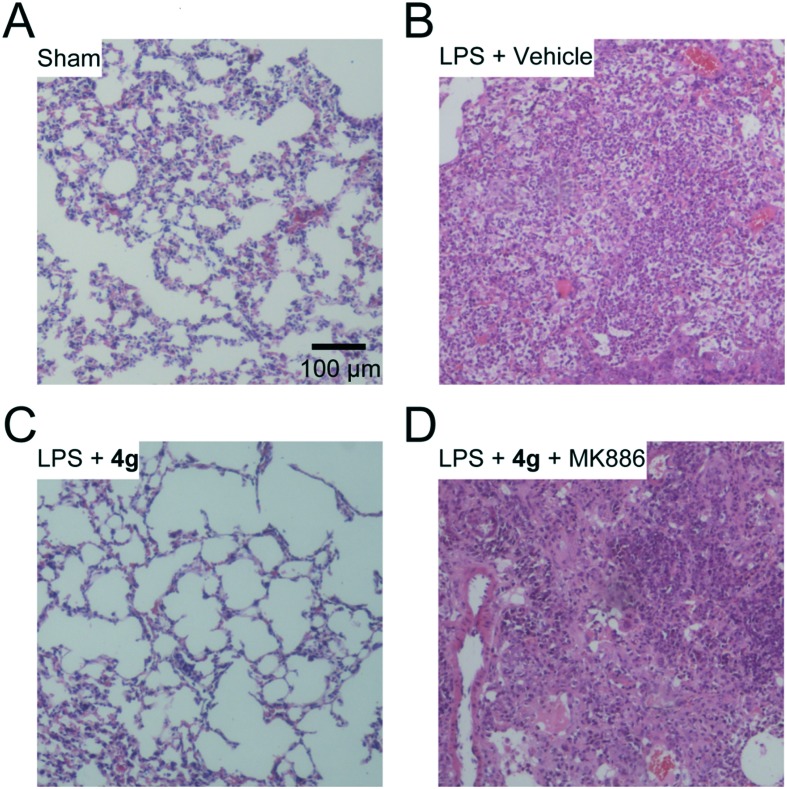

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a complex syndrome that may lead to acute respiratory failure. Gram negative bacteria, especially the lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of these bacteria, are the most common risk factor for ALI. Neutrophil accumulation and severe inflammation are cardinal features of ALI. Consequently, we tested whether treatment of 4g might be beneficial in the LPS-induced ALI model. Five days after LPS intratracheal instillation, pulmonary hemorrhage and edema, thickening of alveolar walls and leukocyte infiltration were found in the lungs of ALI mice (Fig. 3B). Similar to the sham group (Fig. 3A), most leukocytes and edema were cleared in 4g (30 mg kg–1, oral, once daily) treated mice (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the therapeutic effects of 4g were blocked by the PPAR-α antagonist MK886 (2 mg kg–1, i.p., twice daily) (Fig. 3D), suggesting that 4g might alleviate inflammation through a PEA-mediated PPAR-α activation mechanism. These data suggested that 4g promoted clearance of neutrophil infiltration and alveolar repair in the lungs through a PPAR-α activation pathway.

Fig. 3. NAAA inhibitor 4g ameliorated LPS-induced lung injury via a PPAR-α pathway. H&E stained lung sections from sham mice (A) or ALI mice on day 5 with vehicle (B), 4g (C) or MK886 (D) treatment. The images represent at least 75% of whole sections. Original magnification ×10; scale bar, 100 μm.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported the synthesis and evaluation of a series of pyrrolidine amide derivatives, designed as NAAA inhibitors by progressive modification of 1a and 1b. SAR studies suggested that both the substituents or aromatic replacements for the terminal phenyl group can significantly influence the inhibitor activity. The conformationally flexible linkers increased the inhibitory potency of the compounds but reduced their selectivity over FAAH. The conformationally restricted linker may adversely affect their inhibitor potency toward NAAA but enhance the compound selectivity. Several low micromolar NAAA inhibitors (3j, 3k, 4a, and 4g) were developed. Dialysis and kinetic analysis indicated that the representative pyrrolidine amide 4g (E93) inhibited NAAA through a reversible and competitive mechanism, which also showed high anti-inflammatory activities in ALI mice by engaging PPAR-α. The present SAR exploration provides us some promising NAAA inhibitors and an optimized scaffold for the future design of novel NAAA inhibitors, and to explore new therapeutics for inflammation and relative diseases.

Author contributions

YL synthesized the compounds; PZ and LX performed NMR, enzymatic assays and histological analysis; DZ performed the docking study; JR contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; YL and YQ conceived the experiments and designed the experiments. PZ and YL wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81602974 to YL, 81603145 to JR), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2018J05145) and a Fujian Health-Education Research Grant (No. WKJ2016-2-03).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Full experimental details and characterization of the intermediate and final compounds. See DOI: 10.1039/c8md00432c

References

- Tsuboi K., Sun Y. X., Okamoto Y., Araki N., Tonai T., Ueda N. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11082–11092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi K., Takezaki N., Ueda N. Chem. Biodiversity. 2007;4:1914–1925. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N., Tsuboi K., Uyama T. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010;49:299–315. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. X., Tsuboi K., Zhao L. Y., Okamoto Y., Lambert D. M., Ueda N. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1736:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Verme J., Fu J., Astarita G., La Rana G., Russo R., Calignano A., Piomelli D. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:15–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhouayek M., Muccioli G. G. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;19:1632–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoVerme J., Russo R., La Rana G., Fu J., Farthing J., Mattace-Raso G., Meli R., Hohmann A., Calignano A., Piomelli D. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:1051–1061. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhou P., Chen H., Chen Q., Kuang X., Lu C., Ren J., Qiu Y. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;132:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonezzi F. T., Sasso O., Pontis S., Realini N., Romeo E., Ponzano S., Nuzzi A., Fiasella A., Bertozzi F., Piomelli D. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016;356:656–663. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.230516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino S., Ahmad A., Marcolongo G., Esposito E., Allara M., Verde R., Cuzzocrea S., Di Marzo V. Pharmacol. Res. 2015;91:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasso O., Moreno-Sanz G., Martucci C., Realini N., Dionisi M., Mengatto L., Duranti A., Tarozzo G., Tarzia G., Mor M., Bertorelli R., Reggiani A., Piomelli D. Pain. 2013;154:350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Li L., Chen L., Li Y., Chen H., Li Y., Ji G., Lin D., Liu Z., Qiu Y. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13565. doi: 10.1038/srep13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Li Y., Ke H., Li Y., Yang L., Yu H., Huang R., Lu C., Qiu Y. RSC Adv. 2017;7:12455–12463. [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera T., Ponzano S., Piomelli D. Pharmacol. Res. 2014;86:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottemanne P., Muccioli G. G., Alhouayek M. Drug Discovery Today. 2018;23:1520–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzi A., Fiasella A., Ortega J. A., Pagliuca C., Ponzano S., Pizzirani D., Bertozzi S. M., Ottonello G., Tarozzo G., Reggiani A., Bandiera T., Bertozzi F., Piomelli D. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;111:138–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano C., Antonietti F., Duranti A., Tontini A., Rivara S., Lodola A., Vacondio F., Tarzia G., Piomelli D., Mor M. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5770–5781. doi: 10.1021/jm100582w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhouayek M., Bottemanne P., Subramanian K. V., Lambert D. M., Makriyannis A., Cani P. D., Muccioli G. G. FASEB J. 2015;29:650–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-255208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Chen Q., Yang L., Li Y., Zhang Y., Qiu Y., Ren J., Lu C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;139:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armirotti A., Romeo E., Ponzano S., Mengatto L., Dionisi M., Karacsonyi C., Bertozzi F., Garau G., Tarozzo G., Reggiani A., Bandiera T., Tarzia G., Mor M., Piomelli D. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:422–426. doi: 10.1021/ml300056y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelik A., Gebai A., Illes K., Piomelli D., Nagar B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E10032–E10040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811759115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranti A., Tontini A., Antonietti F., Vacondio F., Fioni A., Silva C., Lodola A., Rivara S., Solorzano C., Piomelli D., Tarzia G., Mor M. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:4824–4836. doi: 10.1021/jm300349j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Realini N., Solorzano C., Pagliuca C., Pizzirani D., Armirotti A., Luciani R., Costi M. P., Bandiera T., Piomelli D. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1035. doi: 10.1038/srep01035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y., Ren J., Ke H., Zhang Y., Gao Q., Yang L., Lu C., Li Y. RSC Adv. 2017;7:22699–22705. [Google Scholar]

- Migliore M., Pontis S., Fuentes de Arriba A. L., Realini N., Torrente E., Armirotti A., Romeo E., Di Martino S., Russo D., Pizzirani D., Summa M., Lanfranco M., Ottonello G., Busquet P., Jung K. M., Garcia-Guzman M., Heim R., Scarpelli R., Piomelli D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:11193–11197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vago R., Bettiga A., Salonia A., Ciuffreda P., Ottria R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017;25:1242–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Yang L., Chen L., Zhu C., Huang R., Zheng X., Qiu Y., Fu J. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor M., Lodola A., Rivara S., Vacondio F., Duranti A., Tontini A., Sanchini S., Piersanti G., Clapper J. R., King A. R., Tarzia G., Piomelli D. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:3487–3498. doi: 10.1021/jm701631z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano C., Zhu C., Battista N., Astarita G., Lodola A., Rivara S., Mor M., Russo R., Maccarrone M., Antonietti F., Duranti A., Tontini A., Cuzzocrea S., Tarzia G., Piomelli D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:20966–20971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907417106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J. Z., Parkkari T., Laitinen T., Kaczor A. A., Saario S. M., Savinainen J. R., Navia-Paldanius D., Cipriano M., Leppanen J., Koshevoy I. O., Poso A., Fowler C. J., Laitinen J. T., Nevalainen T. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:8484–8496. doi: 10.1021/jm400923s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponzano S., Berteotti A., Petracca R., Vitale R., Mengatto L., Bandiera T., Cavalli A., Piomelli D., Bertozzi F., Bottegoni G. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:10101–10111. doi: 10.1021/jm501455s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derosa G., Maffioli P., Sahebkar A. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;928:173–184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio L. V., Justinova Z., Goldberg S. R. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;138:84–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.