Abstract

Background

Older patients (≥65 years old) experience high rates of adverse outcomes after an emergency department (ED) visit. Reliable tools to predict adverse outcomes in this population are lacking. This manuscript comprises a study protocol for the Risk Stratification in the Emergency Department in Acutely Ill Older Patients (RISE UP) study that aims to identify predictors of adverse outcome (including triage- and risk stratification scores) and intends to design a feasible prediction model for older patients that can be used in the ED.

Methods

The RISE UP study is a prospective observational multicentre cohort study in older (≥65 years of age) ED patients treated by internists or gastroenterologists in Zuyderland Medical Centre and Maastricht University Medical Centre+ in the Netherlands.

After obtaining informed consent, patients characteristics, vital signs, functional status and routine laboratory tests will be retrieved. In addition, disease perception questionnaires will be filled out by patients or their caregivers and clinical impression questionnaires by nurses and physicians. Moreover, both arterial and venous blood samples will be taken in order to determine additional biomarkers. The discriminatory value of triage- and risk stratification scores, clinical impression scores and laboratory tests will be evaluated.

Univariable logistic regression will be used to identify predictors of adverse outcomes. With these data we intend to develop a clinical prediction model for 30-day mortality using multivariable logistic regression. This model will be validated in an external cohort.

Our primary endpoint is 30-day all-cause mortality. The secondary (composite) endpoint consist of 30-day mortality, length of hospital stay, admission to intensive- or medium care units, readmission and loss of independent living.

Patients will be followed up for at least 30 days and, if possible, for one year.

Discussion

In this study, we will retrieve a broad range of data concerning adverse outcomes in older patients visiting the ED with medical problems. We intend to develop a clinical tool for identification of older patients at risk of adverse outcomes that is feasible for use in the ED, in order to improve clinical decision making and medical care.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02946398; 9/20/2016).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-019-1078-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Risk stratification, Older patients, Emergency department, Prognosis

Background

Older patients (≥65 years of age) constitute an increasing population in emergency departments (EDs). They experience more adverse outcomes than younger ED patients [1–3] as their ED visits are often highly urgent and followed by hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, readmission, and mortality (up to 10% within 3 months). In older ED patients with internal medicine (medical) problems, mortality is even higher (23.8% in 3 months) [4].

Risk stratification can be used to identify ED patients who are at high risk of adverse outcomes. This may lead to improvement in medical care and outcome by early start of interventions [5]. Several risk stratification scores have been developed for the older ED population, such as the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) [6] or Triage Risk Stratification Tool (TRST) [7]. Unfortunately, these scores do not accurately identify those who experience adverse outcomes (areas under the curve (AUCs) range from 0.59–0.74) [8–10]. Triage systems (e.g. Manchester Triage System (MTS) [11]) are also used in the ED population but they tend to undertriage older patients [12]. Furthermore, risk stratification scores either applicable to the general ED population (e.g. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score [13]) or to patients with specific diseases (e.g. Abbreviated Mortality ED Sepsis (abbMEDS) score [14] for sepsis) are used. However, these are not validated in the older ED population.

It may be possible that older patients at risk of adverse outcomes can be identified by assessing the disease perception of patients (or caregivers) or clinical intuition or impression of physicians and/or nurses. Indeed, both disease perception and clinical impression are shown to be associated with mortality and morbidity [15–20]. Unfortunately, most studies were conducted in other clinical settings than the ED (e.g. admission units and ICUs) [4, 17, 20] and in younger patients [17, 18, 20]. A second method to assess clinical impression is to ask the ‘surprise question’ (SQ): ‘Would I be surprised if this patient died within the next 12 months?’. The SQ has been studied in cancer and renal failure patients but its diagnostic accuracy for one-year mortality varies considerably [21]. The predictive value of the SQ for short-term mortality in older medical ED patients is unknown.

Laboratory tests may also be useful for identification of older patients at risk of adverse outcomes [4, 22]. In addition, non-routine laboratory tests, such as lactate, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP), procalcitonin (PCT) and d-dimer, may be valuable predictors of adverse outcome as well [23–27]. Since these tests are indicators of serious conditions and diseases (e.g. tissue hypoperfusion, myocardial injury, bacterial infection and thromboembolism) and often present in the older ED population, we hypothesize that these tests can be useful as predictors. Until now, most studies regarding the predictive value of these tests were performed retrospectively [24, 28–33] or in selected, mostly younger, patients [30–38].

We hypothesize that in the early stage of an ED visit, when important treatment decisions have to be made, several factors can predict adverse outcomes. The aims of this multicentre, prospective study are to 1) identify early predictors of adverse outcome in older ED patients, and 2) develop a clinical prediction model for 30-day mortality.

Methods/design

Study design and setting

This prospective multicentre observational cohort study will take place at the EDs of Zuyderland Medical Centre (MC) Heerlen and Maastricht University Medical Centre+ (MUMC+), in the Netherlands. Zuyderland MC is a secondary teaching hospital with 635 beds and 30,000 ED visits/year. MUMC+ is a secondary and tertiary teaching hospital with 700 beds and approximately 23,000 ED visits/year.

Study population

All patients ≥65 years of age, assessed and treated by an internist or gastroenterologist at the EDs during the study period, are eligible for study inclusion. We chose medical ED patients because these patients are at high risk of adverse outcomes after an ED visit [4]. We intend to include 450 patients in Zuyderland MC starting from July 2016, and 150 patients in MUMC+ from September 2016.

Inclusion criteria:

Age ≥ 65 years

Treatment by an internist, gastroenterologist (or emergency physician under supervision of an internist/gastroenterologist)

Informed consent

Exclusion criteria:

Earlier participation in this study

No informed consent

Inability to speak Dutch or English

Admission to a ward of another specialty than internal medicine/gastroenterology

In case a patient is unable to provide informed consent, e.g. in case of delirium, dementia or when a patient is too severely ill to answer the questions, a legal representative can provide informed consent. A legal representative can either be a legal guardian or an immediate family member including their spouse, adult children, parents or adult siblings. The determination, whether or not a patient can provide informed consent for them self, will be based on expect opinion by the attending physician or investigator. Objection by an incapacitated patient or his/her representatives will always lead to exclusion from the study and analysis.

Objectives and outcome

Objectives

- Evaluation of the discriminatory value for adverse outcomes of:

- triage and risk stratification scores:

- Triage score: MTS [11]

- clinical impressions of nurses and physicians, SQ and disease perception of patients

- routine and non-routine laboratory results

Development and validation of a prediction model for short-term mortality and test the predictive ability of this model for the other adverse outcomes/endpoints

Outcomes

Primary endpoint:

30-day (both in- and out-hospital) all-cause mortality

Secondary endpoints:

- Secondary composite endpoint:

- 30-day mortality

- Length of hospital stay (LOS) > 7 days

- Intensive or medium care unit (ICU/MCU) admission

- Unplanned readmission within 30 days after discharge

- Loss of independent living (e.g. discharge to a nursing home/hospice or with palliative care in previously community dwelling patients)

1-year all-cause mortality

Study procedures

Inclusion of patients

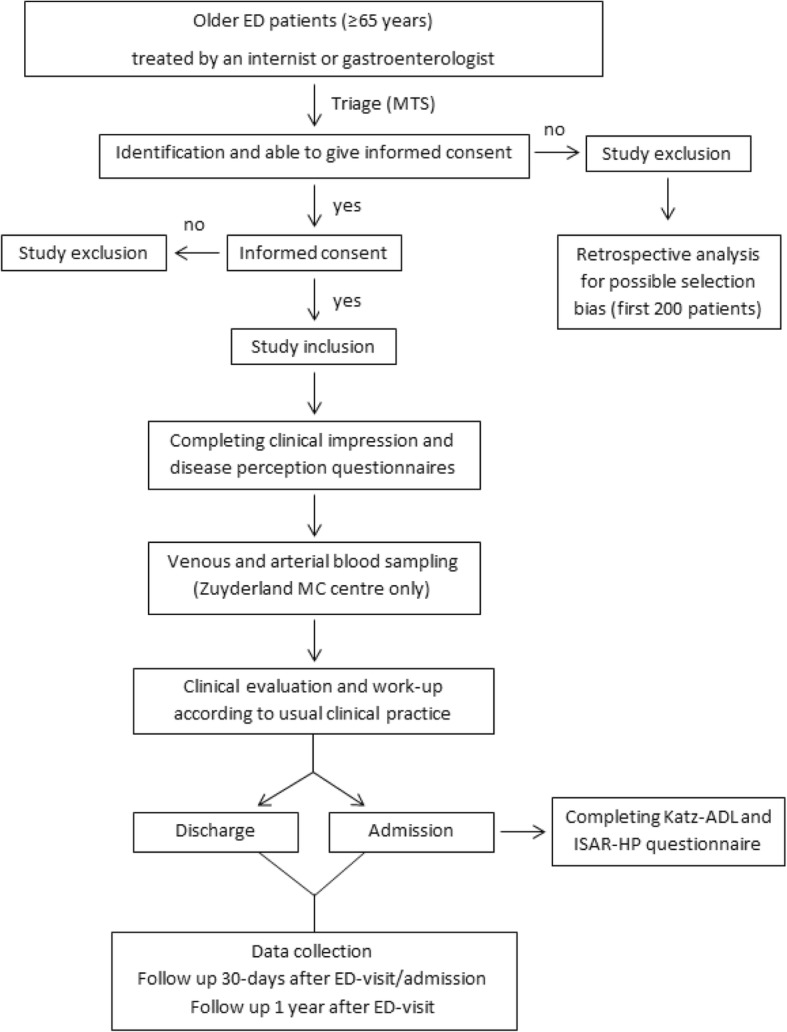

After arrival at the ED, all eligible patients will receive an information brochure and will be asked to participate in the study by the attending physician or investigator. Informed consent must be signed by the patient or his/her legal representative before entering the study. Figure 1 details the study procedure.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study procedure

Questionnaires

The patient/caregiver will receive a questionnaire at the ED that should be filled out as soon as possible. This questionnaire (Additional file 1) contains four questions regarding disease and health perception. The nurse and attending physician both receive a similar questionnaire (Additional files 2 and 3) that has to be filled out before history taking and physical examination and without knowing any diagnostic results. This questionnaire contains six questions regarding the first clinical impression including the SQ. When a patient is admitted to the hospital, a fourth questionnaire (Additional file 4), containing ten questions about the patients’ daily functioning, will be filled out the next day. This questionnaire is used to calculate the ISAR-HP and Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) [43] index score. The results of the questionnaires will only be available for the investigators.

Blood sample collection

In addition to routine blood sampling, two venous blood samples and an arterial blood gas sample will be collected at the ED. Venous blood samples will be stored in a freezer at − 20 degrees Celsius and will be analysed for hs-cTnT, NT-pro-BNP, PCT and d-dimer after 4–12 weeks. Results will be blinded for the physician. Results of the arterial blood gas and lactate level analysis will be presented to the attending physician. Additional venous and arterial blood sample collections will only be performed in Zuyderland MC.

Data collection and follow up

Study parameters will be retrieved from the patient’s medical electronic record and questionnaires. All patients will be followed up for 1 year to obtain long-term outcomes. The following parameters will be collected:

Study parameters collected at the ED:

Demographics (age, sex)

Date and time of ED visit and transport to the ED

Comorbidities: Charlson Comorbidity Index [44], smoking status and presence of cardiovascular disease in family history

Vital signs: heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, Glasgow Coma Scale [45]

First clinical impression (including the SQ) of the physician/nurse and disease perception of the patient/caregiver using questionnaires

Cognitive functioning (dementia, mild cognitive impairment, delirium or normal) based on the diagnosis of a geriatrician and/or on medical records

Number of visits to the hospital in the preceding year

Medication use before the ED visit

Time spent at the ED and the number of physician consultations and radiological examinations during ED stay

Routine laboratory tests: glucose, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphate, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma- glutamyltransferase, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, lactate dehydrogenase, albumin, c-reactive protein, hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocyte count, platelet count, international normalized ratio and activated partial thromboplastin time

Non-routine laboratory tests: arterial blood gas, lactate, hs-cTnT, NT-pro-BNP, PCT and d-dimer

Triage score: MTS

- General risk stratification scores:

- APACHE II score

- ISAR score

- Disease specific stratification scores:

- GBS for upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- abbMEDS score for sepsis

- SOFA score for sepsis

- CURB-65 score for pneumonia

These scores were only calculated when the specific disease for which the score was developed was present.

Diagnosis at the time of discharge from the ED

Study parameters collected in admitted patients only:

- Functional capability:

- Katz ADL index score

- ISAR-HP score

Diagnosis at time of discharge from the hospital

LOS (days)

Living arrangement after discharge: e.g. community dwelling, nursing- or care home etc.

Follow up study parameters collected in all participants:

ICU/MCU admission

All-cause mortality within 30 days of the ED visit

Readmission within 30 days after discharge

Any new relevant medical condition within 1 year after ED visit (e.g. new diagnose of venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease or malignancy)

Possible selection bias

Because physicians must give priority to providing emergency care when the ED is crowded, we expect that not all possible candidates can be included. To investigate possible selection bias, we will retrospectively form a sample of non-included patients and collect the same data, except for the non-routine tests and questionnaires, as in our prospective cohort population. For practical reasons, we intend to include the first 200 non-included candidates in this retrospective sample. Patients who refused to participate in the study will not be included. Baseline characteristics (age and sex) will be analysed for all (non-included) candidates to investigate possible selection bias as well.

Study analysis

Statistical analysis

First, patients characteristics and outcomes will be described. Continuous variables will be reported as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile range and categorical variables as proportions. Valid percentages will be used when values are missing.

Secondly, we will quantify the ability of the risk-stratification scores, clinical impression scores and non-routine laboratory tests to discriminate between the presence and absence of the different endpoints separately using the area under the receiver operator characteristics curve (AUC-ROC). We will determine their diagnostic accuracy using sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV), likelihood ratios and Youden’s index. For the discriminatory value of risk-stratification scores and clinical impression scores, combined data from both centres will be used. For the non-routine laboratory tests, only data from patients recruited in Zuyderland MC will be used.

Third, we will identify possible predictors of adverse outcome using univariable logistic regression analyses. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) will be calculated. Continuous variables will be checked for nonlinearity and collinearity. In case of missing items, we will use stochastic regression imputation to impute these items using predictive mean matching.

Model development

We will develop a clinical prediction model for 30-day mortality using multivariable logistic regression with predictors that are deemed feasible. We consider predictors feasible when a parameter is available in at least 90% of the participants at the ED, reproducible and easily retrieved. Participants that are prospectively included in Zuyderland MC and MUMC+ will form the derivation cohort and their data will be used for model development. For external validation, we will retrospectively collect data of ED patients to form a validation cohort. For the development and validation of our model the Stiell criteria will be applied [46].

After external validation, we will test the predictive ability of the model for the secondary composite endpoint and test whether addition of clinical impression scores and/or non-routine laboratory tests results in a better prediction of adverse outcomes.

All data will be analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) and R version 3.3.3.

Sample size calculation

Since we will be using logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of 30-day mortality, a minimum of 10 events per candidate predictor is suggested [47]. Expected 30-day mortality in older medical ED patients is assumed to be at least 10% based on previous studies in the Netherlands [4, 48]. Therefore, we decided to include 450 patients in Zuyderland MC and 150 patients in MUMC+ to form the derivation cohort. For external validation of our prediction model, we need approximately 100 events, and therefore, the sample size of the validation cohort will be based on the mortality rate of the derivation cohort (estimation: 800 patients).

Trial status

As of 22/12/2018, the study is still ongoing; we are about to finish the inclusion of patients for the validation cohort and are completing 1 year follow up. A total of 603 participants are included in the derivation cohort from July 2016 until the beginning of February 2017 in the two participating centres. In Zuyderland MC, 450 patients, and in MUMC+, 153 patients are included.

Discussion

Early risk stratification at the ED is extremely important to optimise treatment and improve outcomes in acutely ill older patients. To identify older patients with increased risk of adverse outcomes in an early stage, we need accurate predictors.

In the past decades several studies identified risk factors and predictors of adverse outcomes in the older ED population [4, 8, 49]. However, most of these studies were conducted in an unselected population of older patients, leading to conflicting results. For our study we chose medical ED patients because we assume that this group of patients represent a large group of patients who are highly at risk of adverse outcomes. Furthermore, we chose to evaluate more endpoints (including composite endpoints) because some adverse outcomes exclude others (i.e. dying in-hospital will prevent readmission). We are convinced that for quantification of the risk of adverse outcomes in the older population, more than one endpoint is needed for a reliable clinical appraisal. We consider patients older than 65 years to be old and we chose this cut off based on other well-known screening instruments such as the ISAR [6], the ISAR-HP [39] and TRST [7].

Development and validation of our prediction model for 30-day mortality will be according to the Stiell criteria [46]. Since reliable tools to predict short-term mortality are lacking there is need for such a prediction model (criterion 1). Before conduct of this study, internists, gastroenterologists and geriatricians were consulted on the need of a clinical tool, preferred outcomes to be studied and potentially meaningful predictors. The model will be derived according to methodologic standards and is intended to be easily implemented in routine ED care (criterion 2). Most of the predictors we will select will resemble the morbid state rather that the premorbid state because we hypothesize that that the severity of the disease for which the patient visits the ED (morbid state) may be more important than the premorbid state for prediction of short-term mortality. We aim to externally validate our prediction model in a different ED population (criterion 3). Once we have succeeded in developing and externally validating an accurate model, we intend to implement it into clinical practice by offering an online calculator, which may also be incorporated into a electronical file management system (criterion 4).

The main strengths of the RISE UP study are, in our opinion, its prospective multicentre study design in an ED setting and the use of composite endpoints. We aim to identify predictors of adverse outcomes in an early stage of presentation, in the ED setting, when important decisions need to be made. We will not only evaluate the predictive value of the clinical impression of both the patient, nurse and physician, but also that of routine and non-routine laboratory tests. A possible limitation is that we expect that we cannot include all potential candidates, due to crowding of patients at the ED or other logistic problems. Therefore, we will perform an additional analysis to investigate possible selection bias. In addition, this study will include internal medicine and gastroenterology patients only. If this study yields an accurate model, that model will have to be tested in the overall older ED population. Furthermore, we intend to implement the model into clinical practice by use of an online calculator. Possibly, this may also be incorporated into an electronical file management system or a mobile App.

In summary, the RISE UP study is a prospective multicentre cohort study that aims to identify predictors of adverse outcomes in older medical ED patients. The goal of this study is to develop a practical, feasible tool to identify older ED patients with an increased risk of adverse outcomes in an early stage, in order to improve their care in the future.

Additional files

Emergency department questionnaire for the patient or caregiver. Details the questionnaire of the patient/caregiver which should be filled out in the ED. This questionnaire contains questions regarding disease and health perception. (DOCX 50 kb)

Emergency department questionnaire for the nurse. Details the questionnaire of the nurse which should be filled out in the ED before history taking and physical examination and without knowledge of the diagnostic results. This questionnaire contains questions regarding the first clinical impression including the surprise question. (DOCX 60 kb)

Emergency department questionnaire for the physician. Details the questionnaire of the physician which should be filled out in the ED before history taking and physical examination and without knowledge of the diagnostic results. This questionnaire contains questions regarding the first clinical impression including the surprise question. (DOCX 62 kb)

Functional capability assessment questionnaire. Details the questionnaire regarding the patient’s functional capability two weeks before admission. This questionnaire should be filled out during hospital stay and will be used to calculate the Katz Activities of Daily Living and Identification of Seniors at Risk - Hospitalised Patients score. (DOCX 60 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the funding from Zuyderland MC and we would like to thank all of the patients, nurses and physicians who are part of the study.

Funding

Co-investigator NZ was funded by Zuyderland MC. Analysis of non-routine laboratory tests was also funded by Zuyderland MC. The laboratory site of Zuyderland MC was involved in the design of the study regarding the collection and storage of the venous blood samples and performed the analysis of the non-routine laboratory tests. They were not involved in other aspects of the study design, data collection, interpretation of the results or manuscript writing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- abbMEDS

Abbreviated Mortality ED Sepsis

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living

- APACHE II

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II

- AUC

Area under the curve

- AUC-ROC

Area under the receiver operator characteristics curve

- CI

Confidence intervals

- CURB-65

Confusion, Urea, Respiration, Blood pressure, Age > 65

- ED

Emergency Department

- GBS

Glasgow-blatchford bleeding score

- Hs-cTnT

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- ISAR

Identification of seniors at risk

- ISAR-HP

Identification of seniors at risk - hospitalised patients

- LOS

Length of hospital stay

- MC

Medical Centre

- MCU

Medium care unit

- MTS

Manchester triage score

- MUMC+

Maastricht University Medical Centre+

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- NT-pro-BNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- RISE UP

Risk Stratification in the Emergency Department in Acutely Ill Older Patients

- SOFA

Sepsis-related organ failure assessment

- SQ

Surprise question

- TRST

Triage Risk Stratification Tool

Authors’ contributions

PMS, JB, PWL and NZ are responsible for developing the research questions, study design and statistical analysis plan. SMJK made substantial contributions to the statistical analysis plan. NZ is responsible for study management, collection of data and drafted the manuscript. PMS, JB, SMJK and PWL critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is approved by the medical ethics committee of Zuyderland MC, Heerlen, The Netherlands and MUMC+, Maastricht, the Netherlands (reference number NL55867.096.15). Patients or their legal representative have to sign an informed consent form before study entry. This study is in accordance to the 2013 version of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Risks for participating in this study are expected to be very small to negligible and all patients will receive standard care. Objection by an incapacitated patient will lead to exclusion from the study and analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Noortje Zelis, Email: n.zelis@zuyderland.nl.

Jacqueline Buijs, Email: j.buijs@zuyderland.nl.

Peter W. de Leeuw, Email: p.deleeuw@maastrichtuniversity.nl

Sander M. J. van Kuijk, Email: sander.van.kuijk@mumc.nl

Patricia M. Stassen, Email: p.stassen@mumc.nl

References

- 1.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):238–247. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, Gold G. Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvi F, Morichi V, Grilli A, Giorgi R, De Tommaso G, Dessi-Fulgheri P. The elderly in the emergency department: a critical review of problems and solutions. Intern Emerg Med. 2007;2(4):292–301. doi: 10.1007/s11739-007-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buurman BM, van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, Abu-Hanna A, Levi M, de Rooij SE. Prognostication in acutely admitted older patients by nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1883–1889. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0741-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCusker J, Jacobs P, Dendukuri N, Latimer E, Tousignant P, Verdon J. Cost-effectiveness of a brief two-stage emergency department intervention for high-risk elders: results of a quasi-randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(1):45–56. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Trepanier S, Verdon J, Ardman O. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(10):1229–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meldon SW, Mion LC, Palmer RM, Drew BL, Connor JT, Lewicki LJ, Bass DM, Emerman CL. A brief risk-stratification tool to predict repeat emergency department visits and hospitalizations in older patients discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(3):224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter CR, Shelton E, Fowler S, Suffoletto B, Platts-Mills TF, Rothman RE, Hogan TM. Risk factors and screening instruments to predict adverse outcomes for undifferentiated older emergency department patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/acem.12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao JL, Fang J, Lou QQ, Anderson RM. A systematic review of the identification of seniors at risk (ISAR) tool for the prediction of adverse outcome in elderly patients seen in the emergency department. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(4):4778–4786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cousins G, Bennett Z, Dillon G, Smith SM, Galvin R. Adverse outcomes in older adults attending emergency department: systematic review and meta-analysis of the triage risk stratification tool. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013;20(4):230–239. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283606ba6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackway-Jones K, Group MT. Emergency triage. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossmann FF, Zumbrunn T, Ciprian S, Stephan FP, Woy N, Bingisser R, Nickel CH. Undertriage in older emergency department patients--tilting against windmills? PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e106203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vorwerk C, Loryman B, Coats TJ, Stephenson JA, Gray LD, Reddy G, Florence L, Butler N. Prediction of mortality in adult emergency department patients with sepsis. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(4):254–258. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.053298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Fields SD, Braham RL, Douglas RG., Jr Assessing illness severity: does clinical judgment work? J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(6):439–452. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Braham RL, Fields SD, Douglas RG., Jr Morbidity during hospitalization: can we predict it? J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(7):705–712. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brabrand M, Hallas J, Knudsen T. Nurses and physicians in a medical admission unit can accurately predict mortality of acutely admitted patients: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohacek M, Nickel CH, Dietrich M, Bingisser R. Clinical intuition ratings are associated with morbidity and hospitalisation. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(6):710–717. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beglinger B, Rohacek M, Ackermann S, Hertwig R, Karakoumis-Ilsemann J, Boutellier S, Geigy N, Nickel C, Bingisser R. Physician's first clinical impression of emergency department patients with nonspecific complaints is associated with morbidity and mortality. Medicine. 2015;94(7):e374. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinuff T, Adhikari NK, Cook DJ, Schunemann HJ, Griffith LE, Rocker G, Walter SD. Mortality predictions in the intensive care unit: comparing physicians with scoring systems. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):878–885. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201881.58644.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Adhikari NK. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2017;189(13):E484–e493. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Gelder J, Lucke JA, Heim N, de Craen AJ, Lourens SD, Steyerberg EW, de Groot B, Fogteloo AJ, Blauw GJ, Mooijaart SP. Predicting mortality in acutely hospitalized older patients: a retrospective cohort study. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11(4):587–594. doi: 10.1007/s11739-015-1381-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Datta D, Walker C, Gray AJ, Graham C. Arterial lactate levels in an emergency department are associated with mortality: a prospective observational cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(9):673–677. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-203541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Courtney D, Conway R, Kavanagh J, O'Riordan D, Silke B. High-sensitivity troponin as an outcome predictor in acute medical admissions. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90(1064):311–316. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-132325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luchner A, Mockel M, Spanuth E, Mocks J, Peetz D, Baum H, Spes C, Wrede CE, Vollert J, Muller R, et al. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide in the management of patients in the medical emergency department (PROMPT): correlation with disease severity, utilization of hospital resources, and prognosis in a large, prospective, randomized multicentre trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(3):259–267. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hausfater P, Juillien G, Madonna-Py B, Haroche J, Bernard M, Riou B. Serum procalcitonin measurement as diagnostic and prognostic marker in febrile adult patients presenting to the emergency department. Critical Care (London, England) 2007;11(3):R60. doi: 10.1186/cc5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickel CH, Kuster T, Keil C, Messmer AS, Geigy N, Bingisser R. Risk stratification using D-dimers in patients presenting to the emergency department with nonspecific complaints. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen M, Brandt VS, Holler JG, Lassen AT. Lactate level, aetiology and mortality of adult patients in an emergency department: a cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(9):678–684. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Nouland DP, Brouwers MC, Stassen PM. Prognostic value of plasma lactate levels in a retrospective cohort presenting at a university hospital emergency department. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e011450. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filho RR, Rocha LL, Correa TD, Pessoa CM, Colombo G, Assuncao MS. Blood lactate levels cutoff and mortality prediction in Sepsis-time for a reappraisal? A retrospective cohort study. Shock (Augusta, Ga) 2016;46(5):480–485. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchetti M, Benedetti A, Mimoz O, Lardeur JY, Guenezan J, Marjanovic N. Predictors of 30-day mortality in patients admitted to ED for acute heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(3):444–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang XH, Dong Y, Chen YD, Zhou P, Wang JD, Wen FQ. Serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide level is a significant prognostic factor in patients with severe sepsis among Southwest Chinese population. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(4):517–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta C, Dara B, Mehta Y, Tariq AM, Joby GV, Singh MK. Retrospective study on prognostic importance of serum procalcitonin and amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels as compared to acute physiology and chronic health evaluation IV score on intensive care unit admission, in a mixed intensive care unit population. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19(2):256–262. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.179616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, Nathanson LA, Lisbon A, Wolfe RE, Weiss JW. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(5):524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paneesha S, Cheyne E, French K, Bacchu S, Borg A, Rose P. High D-dimer levels at presentation in patients with venous thromboembolism is a marker of adverse clinical outcomes. Br J Haematol. 2006;135(1):85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knowlson L, Bacchu S, Paneesha S, McManus A, Randall K, Rose P. Elevated D-dimers are also a marker of underlying malignancy and increased mortality in the absence of venous thromboembolism. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(9):818–822. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.076349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Groot B, Verdoorn RC, Lameijer J, van der Velden J. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T is an independent predictor of inhospital mortality in emergency department patients with suspected infection: a prospective observational derivation study. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(11):882–888. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuetz P, Birkhahn R, Sherwin R, Jones AE, Singer A, Kline JA, Runyon MS, Self WH, Courtney DM, Nowak RM, et al. Serial Procalcitonin predicts mortality in severe Sepsis patients: results from the multicenter Procalcitonin MOnitoring SEpsis (MOSES) study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):781–789. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoogerduijn JG, Buurman BM, Korevaar JC, Grobbee DE, de Rooij SE, Schuurmans MJ. The prediction of functional decline in older hospitalised patients. Age Ageing. 2012;41(3):381–387. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet (London, England) 2000;356(9238):1318–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on Sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, Boersma WG, Karalus N, Town GI, Lewis SA, Macfarlane JT. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):377–382. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Jama. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet (London, England) 1974;2(7872):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stiell IG, Wells GA. Methodologic standards for the development of clinical decision rules in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(4):437–447. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models : a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magdelijns FJ, Schepers L, Pijpers E, Stehouwer CD, Stassen PM. Unplanned readmissions in younger and older adult patients: the role of healthcare-related adverse events. Eur J Med Res. 2016;21(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40001-016-0230-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Gelder J, Lucke JA, de Groot B, Fogteloo AJ, Anten S, Mesri K, Steyerberg EW, Heringhaus C, Blauw GJ, Mooijaart SP. Predicting adverse health outcomes in older emergency department patients: the APOP study. Neth J Med. 2016;74(8):342–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Emergency department questionnaire for the patient or caregiver. Details the questionnaire of the patient/caregiver which should be filled out in the ED. This questionnaire contains questions regarding disease and health perception. (DOCX 50 kb)

Emergency department questionnaire for the nurse. Details the questionnaire of the nurse which should be filled out in the ED before history taking and physical examination and without knowledge of the diagnostic results. This questionnaire contains questions regarding the first clinical impression including the surprise question. (DOCX 60 kb)

Emergency department questionnaire for the physician. Details the questionnaire of the physician which should be filled out in the ED before history taking and physical examination and without knowledge of the diagnostic results. This questionnaire contains questions regarding the first clinical impression including the surprise question. (DOCX 62 kb)

Functional capability assessment questionnaire. Details the questionnaire regarding the patient’s functional capability two weeks before admission. This questionnaire should be filled out during hospital stay and will be used to calculate the Katz Activities of Daily Living and Identification of Seniors at Risk - Hospitalised Patients score. (DOCX 60 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.