Abstract

The protein Tau forms abnormal filamentous aggregates described as tangles in the brains of people who have dementia. Structures of two such filaments offer pathways to a deeper understanding of the cause of Alzheimer’s disease. See Article p.185

In the early 20th century, the psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer reported the presence of ‘tangled’ intracellular structures in the autopsied brain of a demented patient. The tangles were later found to consist of abnormal aggregates, known as amyloid fibrils, of the protein Tau1. Tau amyloid fibrils seem to be at the root of dozens of age-related dementias and movement disorders2, most notably Alzheimer’s disease. In a paper online in Nature, Fitzpatrick et al.3 report a crucial step toward understanding Tau amyloid fibrils, describing structures for the two types of Tau amyloid fibril seen in Alzheimer’s disease — paired helical and straight Tau filaments.

Normal Tau stabilizes molecular tracks called microtubules along which cargo is transported within long neuronal projections in the brain. But when Tau is overproduced or shed from microtubules, it stacks up, forming amyloid fibrils of various conformations that spread from cell to cell, killing neurons by an unknown mechanism. Some evidence suggests that the various Tau-related dementias may result from fibrils of different conformations4.

Fitzpatrick et al. extracted Tau amyloid fibrils from the autopsied brain of a 74 year old woman who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease 10 years before death, and visualized the fibrils using a technique called cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM)5. Seventy three of the protein’s 441 amino-acid residues make up the stable core of Tau amyloid fibrils and are clearly visible in the cryoEM maps; the remaining residues at either end of the protein are too poorly ordered to be seen. The C-shaped curve observed in previous low resolution studies6 could now be resolved as stacked copies of the tau protein chain that trace out the letter “C”, make a sharp turn, then return near to the start, hugging the inside of the “C”. One stack forms a protofilament, and two protofilaments wind around each other to form the amyloid fibril (Fig. 1). In the paired helical and straight filaments the two protofilaments contact each other differently — in the former, the two contact symmetrically near the sharp turn, whereas in the latter, the two protofilaments contact asymmetrically nearer to the opposite tip of the “C”

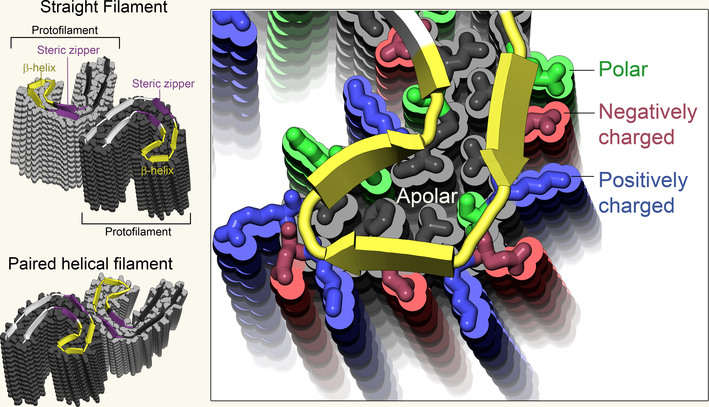

Figure 1 |. Structures of Tau protein filaments.

Fitzpatrick et al.3 extracted and imaged two types of abnormal Tau aggregate — straight filaments and paired helical filaments — from the brain of a patient who had Alzheimer’s disease. In both cases, individual Tau proteins form C shapes (the protein’s main chain is indicated by cartoon ribbons, the side chains are shown in grey), which stack together to form protofilaments. Here, 14 protein layers are shown in each protofilament. Both types of filament are composed of two identical protofilaments, connected at different interfaces. Notable features of the protofilaments include a steric zipper (a common structural motif in aggregated proteins, which repels water) and a β-helix region in which charged residues face outside and apolar residues face inside.

The molecular-level structure reveals some familiar and some unexpected features. The curved stacks of tau chains in the protofilaments run parallel to each other like threads in a sheet. The curved sheet on the outside of the C-shape mate tightly with curved sheet on the inside of the C-shape, excluding water molecules to form a dry interface called a steric zipper7. Exclusion of water lends stability to the filaments thereby impeding their clearance from the cell and is characteristic of all amyloid fibrils studied to date at molecular resolution.

The sharp turn at the tip of the C-shape reveals something unexpected: a structural complexity that rivals that of the evolved globular protein folds. This motif, called a β-helix, requires a precise pattern of polar, apolar, small, and large residues. The complexity of its pattern suggests it could be exploited to develop diagnostic markers to distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from other tauopathies.

Another unexpected feature is the lack of repeated structural motifs. Tau has four imperfect repeats each of an approximately 31 amino-acid sequence, and Fitzpatrick et al. show that two of these, R3 and R4, are included in the core of the fibrils. However, structural similarity between R3 and R4 is limited to a short region spanning only eight amino-acid residues. This disparity is a stark contrast to the common finding in structural biology that similar sequences adopt similar structures and speaks to the challenge of predicting amyloid structure from sequence data alone.

These two Tau filaments are the longest amyloid fibrils visualized at the molecular level to date. That the filaments come directly from a diseased brain confirms that the structure has relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Perhaps most importantly, the techniques used here could be applied to other disease-related amyloid fibrils, for which high-quality structures have proven equally elusive.

Fitzpatrick et al. collected some 2000 images of fibrils at high magnification using cryoEM. The images, which reveal Tau molecules from many angles, were aligned computationally and averaged to reduce noise, permitting 3D reconstruction of the fibril structure. The authors minimized blurring due to small variations in fibril twists by cropping out all but the central, most coherent portion of the aligned images. Developing the software to accomplish these steps has been a major achievement by one of the paper’s senior authors5.

The authors chose cryoEM, rather than x-ray crystallography to analyse Tau amyloid fibrils because it is impossible to coax partially disordered fibrils into crystals. The lack of need of crystalline specimens for cryoEM is its huge advantage. The huge advantage of x-ray crystallography is that crystals hold millions to billions of molecules in the same orientation, providing relatively noise-free information and permitting—in the best cases—resolution of structures at truly atomic scales. An up-and-coming method, microelectron diffraction, shares features of both X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, but so far has not determined amyloid structures as large as tau8,9.

Acknowledgments

In the paper’s acknowledgements, Fitzpatrick et al. state that ‘These findings mark the culmination of a conversation at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology 34 years ago between Aaron Klug and the late Martin Roth about the structural analysis of Alzheimer filaments.’ Indeed, two of the authors started their work on Tau in that research institute in the 1980s. The same institute has sponsored the development of the cryoEM methods for decades, enabling this giant step of a paper, giving us the first molecular level structure of Tau fibrils from the brain of a demented patient. Thus, an implicit lesson emerges from this ground breaking study: long term support is essential for influential science.

References

- 1.Lee VMU, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1121–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goedert M, Eisenberg DS, Crowther RA 2017. Propagation of Tau Aggregates and Neurodegernation. Ann. Rev. Neuroscience, 40, 189–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzpatrick AWP et al. , 2017. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature, 547, 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayers JI, Giasson BI, Borchelt DR. Prion-like Spreading in Tauopathies. Biol Psychiatry. 2017. April 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai X, McMullan G, Scheres SHW, 2016. How cryo-EM is revolutionizing structural biology. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 40, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowther RA. Straight and paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease have a common structural unit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991. March 15;88(6):2288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg DS, Sawaya MR. Structural Studies of Amyloid Proteins at the Molecular Level. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017. January 3. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045104. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi D et al. Three-dimensional electron crystallography of protein microcrystals. 2013. eLife 2, e01345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez JA et al. Structure of the toxic core of a-synuclein from invisible crystals. 2015. Nature 525, 486–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]