Abstract

Actinomycosis osteomyelitis of the jaw bones, particularly in the maxilla, is an extremely rare disease. This report presents two cases of maxillary and two cases of mandibular actinomycosis osteomyelitis, with the diagnosis particularly based on histological procedures. The highly diversified pathogenicity of the phenomenon and the absence of solid diagnostic criteria are discussed. Laboratory challenges are emphasized, and a comprehensive overview of the entity including treatment alternatives is given along with a review of the relevant literature.

Keywords: actinomycosis, alveolar bone loss, cervicofacial, osteomyelitis

Introduction

Actinomycosis of the jaws is a relatively uncommon infection that produces abscesses and open draining sinuses. The principle cause of cervicofacial actinomycosis is Actinomyces israelii. However, Actinomyces naeslundii, Actinomyces viscosus, and Actinomyces odontolyticus are occasionally identified. Actinomyces produces chronic, slowly developing infections, particularly when normal mucosal barriers are disrupted by trauma, surgery, or a preceding infection.1 A break in the integrity of the mucous membranes and the presence of devitalized tissue can result in invasion of the deeper body structures and cause illness.2

Actinomyces strains resemble both bacteria and fungi, thus, they were often considered to be transitional between the two groups of microorganisms. However, most of the fundamental characteristics of Actinomyces indicate that they are, in fact, bacteria. They are anaerobic or facultative in contrast to pathogenic fungi, which are uniformly aerobic. In addition, Actinomyces does not contain sterols in its cell walls, and is sensitive to antibacterial chemotherapeutic agents.3

Actinomycosis is generally a polymicrobial infection requiring the presence of companion bacteria, most frequently anaerobic streptococci, fusiform or Gram-negative bacilli, and Haemophilus species. The associated flora form a kind of symbiosis with Actinomyces species and may cause an anaerobic environment which furthers the growth of this species.4 Hence, these associated bacterial species act as copathogens and participate in the production of infection by elaborating a toxin or enzyme or by inhibiting host defenses. Furthermore, these accompanying species enhance the relatively low invasive power of Actinomyces by eliciting early manifestations of the infection and by treatment failure.4, 5, 6

Involvement of bone is rare, but osteomyelitis sporadically occurs, secondary to the primary infection at primary sites. The infection progresses by direct extension into adjacent tissues. Unlike other infections, actinomycosis does not follow the usual anatomical planes but rather burrows through them and becomes a lobular “pseudotumor”.7

The purpose of this report was to present four cases of Actinomyces osteomyelitis and review the possible pathogenesis of the disease along with the outcomes after proper treatment modalities. A review of the literature on clinical sites, diagnostic methods, and treatment procedures is also included.

Case reports

Case 1

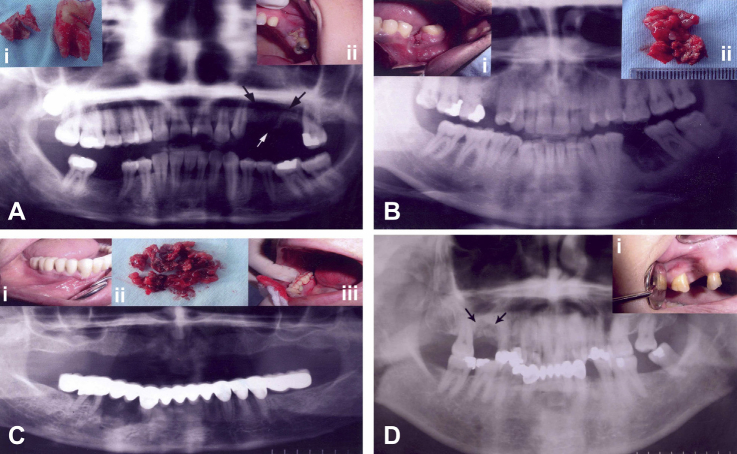

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Oral Surgery Clinic in May 2002. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory. Root-canal treatment had been completed in her left upper first premolar 2 years previously. This was followed by progressively increasing swelling in the oral vestibular region adjacent to the tooth. The swelling also mildly involved the left buccal area. She also described a continuous pain in her tooth. The patient was empirically treated by her dentist with oral administration of ampicillin/sulbactam (50 mg/kg), but after 1 week of gradual and partial recovery, the swelling returned. Because her pain was still present, she asked for her tooth to be extracted and the extraction was performed 2 months prior to her admission to the Department of Oral Surgery Clinic. The patient reported that she had been prescribed oral spiramycine for 20 days after the extraction, but the treatment failed to resolve her pain and swelling. She described a sense of “itching” on her cheek, and an ongoing sensation of pressure and intermittent discomfort around the tooth. She also described pain in the neighboring molar tooth with a gross amalgam restoration (Fig. 1B). Clinical examination revealed an unhealed tooth socket. The color of the adjacent gingiva showed slight erythema resembling desquamative gingivitis (Fig. 1B). Additionally, exposed sequestra were present. On an X-ray examination, the maxillary bone adjacent to the tooth socket showed destruction of the alveolar bone (Fig. 1A). As a result of the clinical and radiological findings, the patient underwent surgical intervention with a preliminary clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis infection.

Figure 1.

(A) Preoperative panoramic radiograph showing an extensive radiolucent lesion in the left maxillary premolar region (arrows). (i) Excised sequester and extracted neighboring molar tooth. (ii) Clinical view showing sequester and erythema of the gingiva in the maxillary premolar region. (B) Preoperative panoramic radiograph with radiolucent and sclerotic areas of the lesion in the left mandibular molar region. (i) Clinical view of an unhealed alveolar socket. (ii) Excisional biopsy material consisting of soft tissue and sequester. (C) Preoperative panoramic view showing radiolucent and radiopaque areas in the right mandibular premolar region below the prosthetic restoration. (i and iii) Preoperative clinical views showing gingival erythema and swelling of the right mandibular premolar region. (ii) Biopsy material. (D) Preoperative panoramic X-ray showing the right maxillary molar area with osteolytic and sclerotic lesion (arrows). (i) Clinical view of unhealed tooth socket and gingival erythema.

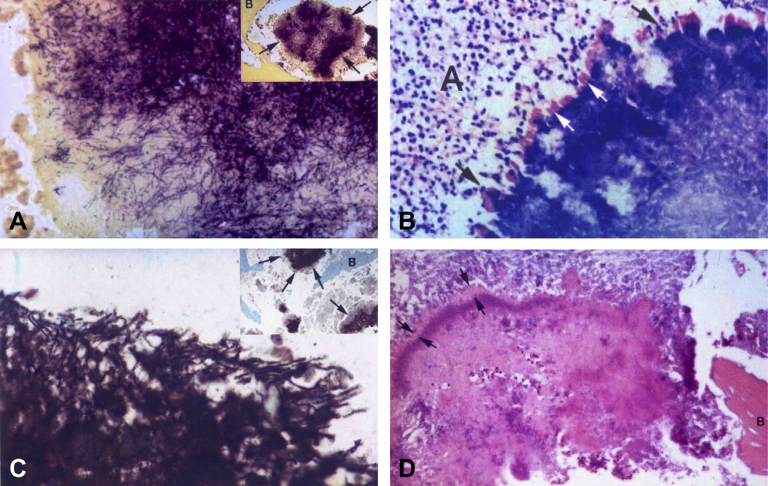

Local infiltration anesthesia was induced, a full mucoperiosteal flap was elevated, and the defect was curetted. The right maxillary first molar adjacent to the area of the lesion was extracted due to the extensiveness of the lesion and complaints of the patient. Curetted tissue from the surgical site was submitted for histopathological and microbiological examination [Fig. 1A(i)]. In hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained sections, fragments of bone and granulation tissue were observed. Hard-tissue specimens included trabeculae of woven bone enclosing marrow tissue and a number of partly resorbed bony sequestra with extensive involvement of microorganisms. For the histological differential diagnosis, sections were also stained with tissue Gram, Giemsa, periodic acid Schiff (PAS), Gomori methenamine silver (GMS), and Ziehl Neelsen stains. The histological appearances were consistent with those of osteomyelitis in association with infection by Actinomyces organisms (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

(A) Photomicrograph of peripherally radiating filaments of the actinomycotic granule (i), (tissue Gram stain, 100×). (ii) Granule is surrounded by trabecular bone. Note the deep-purple Gram-positive filaments (arrows), (tissue Gram stain, 20×). (B) Photomicrograph of deeply stained basophilic actinomycotic granule with prominent peripheral cubs (white arrows) surrounded by polymorphonuclear leucocytes (black arrows) embedded in an abscess (A), (Giemsa stain, 40×). (C) Periphery of actinomycotic granule (i). Note the branching filaments and cocoid elements. (ii) Gomori methamine silver stain of actinomycotic granule (arrows) embedded in an area of suppurative necrosis between bone trabeculae (10×). (D) Photomicrograph of an actinomycotic granule bordered by eosinophilic Splendore–Hoeppli material (between arrows), embedded in fibrino-purulent exudate and surrounded by trabecular bone (B). Note the numerous polymorphonuclear leucocytes within the matrix of the granule (H&E stain, 20×).

Culture of the involved tissue did not demonstrate the presence of Actinomyces. Similarly, no Candida colonies were observed. However, cultures were positive for Gram-positive microorganisms that are common inhabitants of the oral cavity.

Case 2

A 24-year-old otherwise healthy man was referred to the Department of Oral Surgery Faculty Clinic because of an unhealed extraction socket in the region of the lower left first molar that had been extracted 2 years prior to referral. The tooth had been asymptomatic, and the patient could not recall ever experiencing pain. However, on clinical examination, the socket seemed like a freshly extracted one [Fig. 1B(i)]. A panoramic radiograph of the area revealed ill-defined bony changes with osteolytic and osteosclerotic areas (Fig. 1B). There was no soft-tissue involvement.

Actinomycosis was suspected in accordance with clinical and radiological findings; therefore, the patient underwent surgical intervention with a preliminary clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis. Necrotic tissue curetted during the surgical intervention [Fig. 1B(ii)] was submitted for histopathological evaluation, and sections were primarily stained with H&E, and then similar staining procedures were performed with each of the stains used in Case 1. On histopathological examination, trabeculae of necrotic woven bone enclosing Actinomyces granules with bone marrow and a number of partially resorbed bony sequestra, nonspecific inflammatory cell infiltrates, vascular proliferations, and granulation tissue were seen. Within the granulation tissue were granules surrounded by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Fig. 2B). The periphery of the Actinomyces granules showed radiating, basophilic filaments and eosinophilic, club-shaped ends (Fig. 2B and C). However, culture of the tissue was not positive either for Actinomyces or Candida. By contrast, Gram-positive cocci were observed on cultures of the involved tissue.

Case 3

A 67-year-old woman had her lower right first premolar tooth extracted due to severe pain. Extraction of the tooth was performed without complications 5 months prior to referral to the Department of Oral Surgery Faculty Clinic. A fixed prosthetic restoration had been applied to the area, but her pain did not resolve. She had also been empirically treated by her dentist with oral administration of amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium for 2 months. She was referred to our clinic with the complaint of a partially healed extraction socket and gingival swelling accompanied by mild pain [Fig. 1C(i) and C(iii)]. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory. A radiographic examination showed a large periapical osteolytic area and sequestra (Fig. 1C).

A typical clinical picture with a long-lasting infection and gingival swelling strongly suggested actinomycosis; therefore, the patient underwent surgical intervention with a preliminary clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis.

The periapical defect was curetted, and the sequestra were surgically removed [Fig. 1C(ii)]. Curetted tissue from the surgical site was submitted for histopathological and microbiological examinations. The histopathological examination of the curetted tissue revealed that there were reactive bone and chronically inflamed granulation and fibrous tissues. Actinomyces was identified primarily on H&E-stained sections (Fig. 2D). Additionally, tissue sections were stained with Giemsa, PAS, GMS, and Ziehl Neelsen stains, as similarly done with the previous two cases. The attempts to grow Actinomyces from the cultures taken at the time of the operation were not productive. However, cultures were positive for Gram-positive cocci.

Case 4

A 60-year-old woman was referred to our clinic with a complaint of mild pain in her right maxillary molar area. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory. Root-canal treatment had been completed in her right upper first molar 2 years previously. The continuous pain in her tooth had not subsided, therefore, she had asked for the tooth to be extracted 1 year after completion of her endodontic treatment. Meanwhile, the patient had been empirically treated by her dentist with oral administration of various antibiotics, but she could not recall either the type or duration. She still described ongoing pain, particularly on pressure, on her admission to the Department of Oral Surgery Faculty Clinic in January 2003. Her clinical examination revealed an unhealed tooth socket, and the adjacent gingiva showed slight erythema [Fig. 1D(i)]. On X-ray examination, the maxillary bone adjacent to the tooth socket showed destruction of the alveolar bone (Fig. 1D). Based on the clinical and radiological findings, the patient underwent surgical intervention with a preliminary clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis.

Necrotic tissue curetted during the surgical intervention was submitted for histopathological and microbiological examinations. Histological sections were prepared and primarily stained with H&E due to the diagnosis of actinomycosis, and then similar staining procedures were done with each of the stains used in the above-described cases. In the histopathological examination, trabeculae of necrotic woven bone enclosing Actinomyces granules with bone marrow and a number of partially resorbed bony sequestra, and granulation tissue were observed. The periphery of the Actinomyces granules had radiating filaments with club-shaped ends. However, culture of the tissue was negative for Actinomyces. Peptostreptococcus species were present in the culture of curetted tissue.

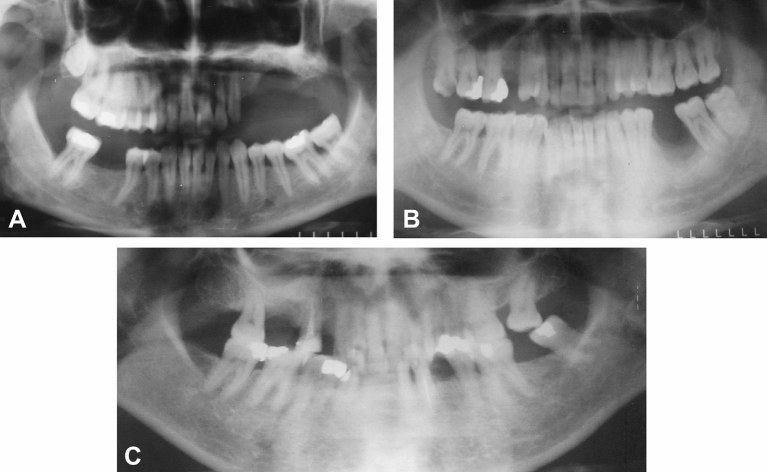

The histopathological characteristics were typical of actinomycosis for all four cases, thus, treatment proceeded accordingly. Treatment with 2 g oral penicillin was initiated and continued for 2 months in all patients. Postoperative healing was uneventful, and no recurrence of the lesions occurred during 1 year follow-up of the presented cases (Fig. 3A–C).

Figure 3.

Postoperative panoramic radiographs showing the healing of bone in the (A) left maxillary premolar, (B) left mandibular molar, and (C) maxillary molar regions of Case 1, Case 2, and Case 4.

Discussion

A systematic search of the MEDLINE database(1952–2011) was performed using the terms “osteomyelitis, jaw”, “actinomycosis, mandibular”, “actinomycosis”, and “osteomyelitis”. Cases among children younger than 18 years old (i.e., pediatric cases) were omitted (Table 1). As can be seen from Table 1, 10 of 30 reports were made during the past 11 years, whereas 20 reports were made during the previous 48-year period.6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 This is believed to be due to modern diagnostic techniques used to identify the involved Actinomyces species. Almost all of the reported cases resolved after proper surgical treatment and antimicrobial therapy.

Table 1.

Reports of actinomycosis osteomyelitis affecting jaws.

| Authors (y) | Location of bone infection | Diagnostic method | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garg et al8 (2011) | Palatina | Surgery + IV antibiotics | |

| Vigliaroli et al9 (2010) | Mandible | PR + CT | Surgery + IV + local antibiotics |

| Finley & Beeson10 (2010) | Mandible | CT + MRI + nuclear scan + hematology | Oral antibiotics |

| Kaplan et al11 (2009) | 60% mandible 40% maxilla |

Histomorphometry | Surgery + IV antibiotics + Hyperbaric oxygen |

| Vazquez et al12 (2009) | Maxilla + mandible | Culture + PR + nuclear scan | Surgery + IV antibiotics |

| Sharkawy13 (2007) | Mandible | Histomorphometry + culture | Surgery + IV antibiotics |

| Hansen et al14 (2007) | Histology + PCR + SEM evaluation | Not performed | |

| Tarner et al15 (2004) | Maxilla | MRI + histology + hematology | Not performed |

| Curi et al16 (2000) | Maxilla + mandible | Histology + microbiology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Liu et al17 (1998) | Maxilla | NA | NA |

| Bartkowski et al18 (1998) | Mandible | Bacteriology + histopathology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Sakellariou19 (1996) | Mandible | Histopathology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Rubin & Krost20 (1995) | Maxilla | NA | NA |

| Watkins et al21 (1991) | Mandible | Bacteriology + histopathology | NA |

| Nuss et al22 (1989) | Mandible | NA | NA |

| Saxby & Lloyd23 (1987) | NA | NA | |

| Gupta et al24 (1986) | Mandible | Bacteriology + smear + sensitivity tests | NA |

| Yenson et al25 (1983) | Mandible + maxilla | NA | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Price et al26 (1982) | Mandible | Bacteriology + histopathology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Walker27 (1981) | Mandible | NA | NA |

| Fergus & Savord28 (1980) | Maxilla | Histopathology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Pinzur29 (1979) | Maxilla + mandible | NA | NA |

| Yakata et al30 (1978) | Mandible | Culture + Gram stain | Systemic antibiotics |

| Oppenheimer et al6 (1978) | Mandible | Bacteriology + histopathology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Ermolov31 (1975) | Mandible | NA | NA |

| Stenhouse32 (1975) | Intraoral | Histopathology | Surgery + systemic antibiotics |

| Stenhouse & MacDonald33 (1974) | Maxilla + mandible | NA | NA |

| Goldstein et al34 (1972) | Maxilla | PAS + Brown–Brenn stain | NA |

| Gold & Doyne35 (1952) | Alveolar process | NA | NA |

CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NA = not available; PAS = Periodic acid–Schiff; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PR = panoramic radiography; SEM = scanning electron microscopy.

A chronic, persistent, purulent, localized infection associated with unhealed tooth sockets characterized all four of the actinomycosis cases presented in this report. A jaw fracture, oral surgery, an infected tooth socket, deep periodontal pockets, and a root canal may serve as points of entry for microorganisms, with the consequent development of actinomycosis. Therefore, the prerequisite for the development of endogenous disease is the transport of pathogens into tissue layers with an anaerobic environment.32, 36 These organisms lack tissue-decomposing enzymes (hyaluronidases), therefore, they require the aid of other accompanying bacterial flora to achieve pathogenicity.37 The presence of accompanying bacteria in all of the presented cases revealed by microbiological culture adheres well to the accepted concept of the combination of Actinomyces with other bacteria, particularly streptococci and staphylococci, having a synergistic effect in the pathogenicity of cervicofacial actinomycosis.38 As a soft-tissue infection progresses, it penetrates by direct extension to adjacent tissues, that is, bone. However, it was not clear in the present cases whether the actinomycosis was the primary infection or a secondary infection to a pre-existent nonspecific local osteomyelitis of the alveolar bones.

Only a few cases of actinomycosis osteomyelitis have been reported in the literature.20, 39 Although the pathomechanism of actinomycosis osteomyelitis is unclear, it is suggested that inflammation begins when the normal composition of the microbial flora is disturbed, and chronic inflammation leads to localized pathological changes in the bone. It is assumed that the mandibular predominance of the disease stems from the relatively poor vascularization of the condensed cortical bone in the mandible with a similar mechanism that predisposes it to osteoradionecrosis.40 Although two of the cases reported here had mandibular involvement, Case 1 and Case 4 were noteworthy in that the actinomycotic osteomyelitis was of maxillary origin, which is extremely rare compared to mandibular actinomycotic osteomyelitis, probably because of the good blood supply of the face, which provides more oxygen and better circulation.34 Hence, the present cases may serve as a reminder to consider actinomycosis as a possible cause of osteomyelitis in the maxilla in persistent infections.

An actinomycotic infection was not confirmed in the cultures of any case reported here. The diagnosis of actinomycosis was based upon morbid anatomical, radiological, and microscopic evidence, particularly H&E-stained preparations rather than bacteriological culture and identification. Major difficulties in bacteriological identification of the present cases may have been due to the possible suppressive effect of prior antimicrobial therapy that was blindly used for persistent infections and/or concomitant aerobic and anaerobic bacterial overgrowth.28, 40 A diagnosis of actinomycosis is best made by culture, but <50% of cases are positive due to numerous problems associated with culturing these organisms.41 The necessity for special handling of specimens in order to obtain positive cultures of anaerobic organisms was highlighted.6 For this reason, a histopathological examination is also highly recommended.34, 40, 42 Herein, the diagnosis depended upon the morphology and staining characteristics of the microorganism. Actinomyces species strongly stain positive for H&E, PAS, and Giemsa. Additionally, GMS staining is also useful for demonstrating the filaments.43

Actinomycosis is difficult to diagnose based on typical clinical features and direct identification, and/or isolation of the infecting organism from a clinical specimen may be laborious, therefore, nucleic acid probes and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods have been developed for rapid and accurate identification. Actinomycosis is generally considered a polymicrobial infection.14 For a diagnosis involving osteomyelitis of the jaws, molecular testing is considered a suitable method. In a study by Hansen et al,44 a PCR was used to detect A. israelii in bone specimens, which were decalcified in trichloroacetic acid, and a remarkable reduction in sensitivity was reported. In a subsequent study by the same group, it was confirmed that a PCR analysis of A. israelii resulted in a higher sensitivity if milder decalcification, such as with ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA), was applied.14 Thus, this molecular diagnostic approach was recommended even for bone biopsies that were primarily used for histology.14

Current PCR research in the bacteriological laboratory focuses on applying this technique to detect pathogens directly in clinical samples. It is clear that this approach has several advantages over culture techniques for slowly growing or noncultivable bacteria. However, comparing PCR to conventional identification procedures, PCR is more expensive and requires experienced research personnel.

After arriving at a sound diagnosis, it is recommended that treatment of actinomycosis infection should be vigorous. After removing the foci of infection, including resection of the sequestrated bone and excision of all granulation tissue until healthy tissue is exposed, prolonged administration of antibiotics, preferably penicillin, is recommended.40, 45 It has been concluded that additional exposure time to antibiotics is necessary because lysis of Actinomyces species occurs at a slow rate compared to most other bacteria.46 As demonstrated in all four of our present cases, the prognosis for satisfactory resolution is excellent, and recurrence after adequate treatment is rare.47

A clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis may be difficult because the condition might not provoke pain at any or in later stages, and the cause is frequently not recognized on presentation.48 However, any unidentified mass, facial swelling, or persistent infection particularly after endodontic therapy or tooth extraction, regardless of its nontraumatic history is suggestive of actinomycosis.45, 49 Diagnosis of this infection should be actively attempted in all instances of persistent oral infections because progressive actinomycosis, particularly in the maxilla, is likely to have relatively serious consequences if it is not diagnosed.34 It is reasonable to assume that early diagnosis can significantly improve outcomes.

References

- 1.Murray R.P., Kobayashi G.S., Pfaller M.A., Rosental K.S. 2nd ed. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1994. Medical Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafer W.G., Hine M.K., Levy B.M. 3rd ed. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1974. A Textbook of Oral Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster G.S. 3rd ed. Decker; Philadelphia, PA: 1990. Oral Microbiology and Infectious Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennhoff D.F. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1198–1217. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandran Nair P.N., Schroeder H.E. Periapical actinomycosis. J Endod. 1984;10:567–570. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(84)80102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oppenheimer S., Miller G.S., Knopf K., Blechman H. Periapical actinomycosis. An unusual case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;46:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson L.J. 4th ed. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2002. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; pp. 428–430. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg R., Schalch P., Pepper J.P., Nguyen Q.A. Osteomyelitis of the hard palate secondary to actinomycosis: a case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90:E11–E12. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vigliaroli E., Broglia S., Iacovazzi L., Maggiore C. Double pathological fracture of mandibula caused by actinomycotic osteomyelitis: a case report. Minerva Stomatol. 2010;59:507–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finley A.M., Beeson M.S. Actinomycosis osteomyelitis of the mandible. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:118.e1–118.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan I., Anavi K., Anavi Y. The clinical spectrum of Actinomyces-associated lesions of the oral mucosa and jawbones: correlations with histomorphometric analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vázquez E., López-Arcas J.M., Navarro I., Pingarrón L., Cebrián J.L. Maxillomandibular osteomyelitis in osteopetrosis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;13:105–108. doi: 10.1007/s10006-009-0151-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharkawy A.A. Cervicofacial actinomycosis and mandibular osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen T., Kunkel M., Springer E. Actinomycosis of the jaws – histopathological study of 45 patients shows significant involvement in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis and infected osteoradionecrosis. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:1009–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarner I.H., Schneidewind A., Linde H.J. Maxillary actinomycosis in an immunocompromised patient with longstanding vasculitis treated with mycophenolate mofetil. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1869–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curi M.M., Dib L.L., Kowalski L.P., Landman G., Mangini C. Opportunistic actinomycosis in osteoradionecrosis of the jaws in patients affected by head and neck cancer: incidence and clinical significance. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:294–299. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C.J., Chang K.M., Ou C.T. Actinomycosis in a patient treated for maxillary osteoradionecrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:251–253. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartkowski S.B., Zapala J., Heczko P., Szuta M. Actinomycotic osteomyelitis of the mandible: review of 15 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1998;26:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(98)80037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakellariou P.L. Periapical actinomycosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1996;12:151–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1996.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin M.M., Krost B.S. Actinomycosis presenting as a midline palatal defect. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:701–703. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watkins K.V., Richmond A.S., Langstein I.M. Nonhealing extraction site due to Actinomyces naeslundii in patient with AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:675–677. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90272-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuss K., Schäffer E., Köstlin R.G. Abscess forming mandibular osteomyelitis following actinomycosis. Tierarztl Prax. 1989;17:15,109–15,111. [Article in German] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxby M.S., Lloyd J.M. Actinomycosis in a patient with juvenile periodontitis. Br Dent J. 1987;163:198–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta D.S., Gupta M.K., Naidu N.G. Mandibular osteomyelitis caused by Actinomyces israelii. Report of a case. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yenson A., deFries H.O., Deeb Z.E. Actinomycotic osteomyelitis of the facial bones and mandible. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;91:173–176. doi: 10.1177/019459988309100211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price J.D., Craig G.T., Martin M.V. Actinomyces viscosus in association with chronic osteomyelitis of the mandible. Br Dent J. 1982;153:331–333. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker S., Middelkamp J.N., Sclaroff A. Mandibular osteomyelitis caused by Actinomyces israelii. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;51:243–244. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fergus H.S., Savord E.G. Actinomycosis involving a periapical cyst in the anterior maxilla. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49:390–393. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinzur G.S. Actinomycosis of the maxillofacial area in jaw fractures. Stomatologiia. 1979;58:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yakata H., Nakajima T., Yamada H., Tokiwa N. Actinomycotic osteomyelitis of the mandible: report of case. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:720–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ermolov V.F. Mandibular fractures complicated by actinomycosis and tuberculosis. Stomatologiia. 1975;54:93–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenhouse D. Intraoral actinomycosis: report of five cases. Oral Surg. 1975;39:547–552. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stenhouse D., MacDonald D.G. Low grade osteomyelitis of the jaws – with actinomycosis. Int J Oral Surg. 1974;3:60–64. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(74)80080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein B.H., Sciubba J.J., Laskin D.M. Actinomycosis of maxilla: review of literature and report of case. J Oral Surg. 1972;30:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gold I., Doyne E.E. Actinomycosis with osteomyelitis of the alveolar process. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1952;5:1056–1063. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(52)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silbermann M., Chiminello F.J., Doku H.C., Maloney P.L. Actinomycosis: report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1975;90:162–165. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1975.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strassburg M., Knolle G. 2nd ed. Quintessence Publishing; Chicago, IL: 1994. Diseases of the Oral Mucosa. A Color Atlas; pp. 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadeghi E.M., Hopper T.L. Actinomycosis involving a mandibular odontoma. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;107:434–437. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nathan M.H., Radman W.P., Barton H.L. Osseous actinomycosis of the head and neck. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1962;87:1048–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagler R.M., Ben-Arieh Y., Laufer D. Case report of regional alveolar bone actinomycosis: a juvenile periodontitis-like lesion. J Periodontol. 2000;71:825–829. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rush J.R., Sulte H.R., Cohen D.M., Makkawy H. Course of infection and case outcome in individuals diagnosed with microbial colonies morphologically consistent with Actinomyces species. J Endod. 2002;28:613–618. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200208000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters E., Lau M. Histopathologic examination to confirm diagnosis of periapical lesions: a review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:598–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandler F.W., Watts J.C. Fungal diseases. In: Damjanov I., Linder J., editors. Anderson's Pathology. 10th ed. Mosby-Year Book; St. Louis, MO: 1989. pp. 951–982. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen T., Kunkel M., Kirkpatrick C.J., Weber A. Actinomyces in infected osteoradionecrosis – underestimated? Hum Pathol. 2006;37:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garant P.R. Light and electron microscopic observations of osteoclastic alveolar bone resorption in rats monoinfected with Actinomyces naeslundii. J Periodontol. 1976;47:717–723. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.12.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnard D., Davies J., Figdor D. Susceptibility of Actinomyces israelii to antibiotics, sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 1996;29:320–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagler R., Peled M., Laufer D. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:652–656. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeansonne B.G. Periapical actinomycosis: a review. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aldred M.J., Talacko A.A. Periapical actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:614–620. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]