Abstract

Maintaining a competitive edge is increasingly imperative for surgical research teams. To publish as efficiently and effectively as possible, research teams should apply business strategies and theories in everyday practice. Drawing from concrete examples in both the corporate and nonprofit worlds, and by reflecting on the practices of the Michigan Comprehensive Hand Center for Innovation Research (M-CHOIR) this paper identifies important business theories that can be applied to plastic surgery research and their potential applications in practice from developing a realistic vision and strategies, to their effective execution, and, finally, reflective evaluation for continual improvement.

Keywords: Teamwork, clinical research, strategies, team, leadership

In 2003, leaders in medicine and clinical studies gathered at the Institute of Medicine’s Clinical Research Roundtable to address the issue of the shrinking field of clinical research, and to identify challenges facing researchers.1,2 Many of their solutions were focused on improving the dynamic of a clinical research team.1 A successful research team typically consists of numerous members with differing levels of training and expertise, who work together to execute and publish studies in a practical and impactful manner. In a review identifying differences in perceived necessary skills for physician leaders following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the number of papers mentioning team and team-building skills increased 244%.3 As clinical research has evolved, teamwork and collaboration have become essential for answering even simple research questions. Granting teamwork in healthcare research is not new, the increased pressure to “publish or perish” has led to more collaborative efforts and multi-disciplinary teamwork to generate impactful publications.4 Although the mindset of “publish or perish” can pressure researchers, other motivations drive research as well, particularly academic curiosity and desire to improve healthcare from treatment development to applications of those new treatments. Developing a diverse research team consisting of members with compatible skillsets is imperative to the team’s success.

In this article, we reflect upon the experiences of the Michigan Comprehensive Hand Center for Innovation Research (M-CHOIR). M-CHOIR has enjoyed unprecedented success in recent years, publishing 46 papers in 11 different journals and leading two longitudinal multicenter NIH funded R01 studies, in addition to receiving a number of other foundation grants in 2016. M-CHOIR began in 1998 with 2 members, and has grown to a team of over 40. Team members include faculty, fellows, research staff, and students. M-CHOIR is focused on various types of clinical trials, health policy, and outcomes research including epidemiological studies, economic analyses, population-based research, and social science research.

Although some researchers have examined the role of teamwork in healthcare,5–8 to the best of our knowledge, none have yet examined the implementation of business strategies in clinical research. Business strategies can be used to increase productivity and to help a research team remain competitive. Our research group has implemented business strategies to adjust to changes in clinical research. In this paper, our objectives are to (1) summarize our model of an effective research team and (2) present an approach that can be used to derive strategies that foster productivity in a surgical research setting. We have shared our own reflections to help illustrate the effectiveness of various strategies implemented by our research group.

Conceptual Model

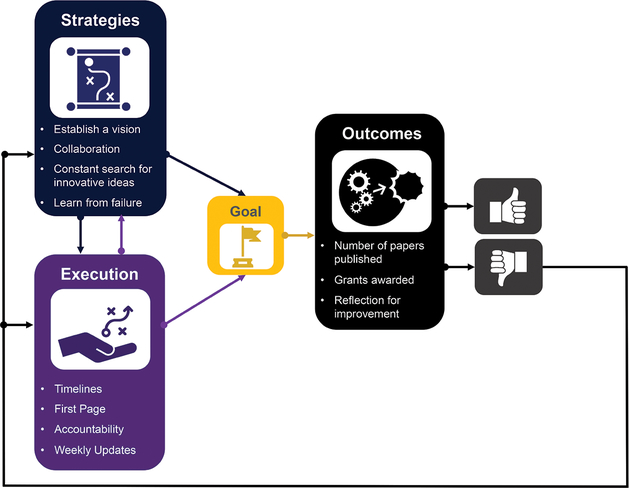

Various models have been proposed to illustrate the structure of an effective team.9–13 The input-process-output (IPO) framework proposed by McGrath remains a commonly accepted model.12 According to this model, a team is shaped by inputs (team composition, individuals in the team and their characteristics), processes (how team members work together and apply their resources to attain the team’s goal), and outputs (how the team performs and meets their goal). We used this framework to develop a model tailored for clinical research (Figure 1). In an effective research team, the PI, in addition to all other members, must (1) define the strategies that are best suited for the team, (2) ensure the leaders are executing the defined strategies, and (3) evaluate the outcomes in accordance to whether or not the strategies helped the team reach its goal. The general framework can be used by various research teams, both clinical and basic science, by adjusting the strategies used and the methods of strategy execution and outcome evaluation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Depicting an Approach to Developing Strategies for an Effective Team

Strategy

Strategy is defined as “a plan of action or policy designed to achieve a major or overall goal.” Within the business world, these goals are meant to maximize sales and profits of a product or service. In the non-profit realm, the goal is to increase the quantity and efficiency of delivering aid, which is achieved through fundraising prior to demonstrating a result that often may not have a measurable outcome. Unlike for-profit businesses, profit and revenue are poor measures for success for nonprofits and performance is a better indicator.14 However, performance is not a universal measurement and can be subjective. Therefore, charitable nonprofits are required to publish annual reports detailing their impact and financial distributions.15 The difference in strategy between for-profit and non-profit corporations can be seen by comparing Google and Doctors Without Borders, both of which are highly successful and respected organizations. Google uses a 3-pronged enterprise strategy, fostering a culture of fast innovation, targeting enterprise developers, and driving towards digital priorities; these goals strive towards their mission of creating popular consumer products that organize the world’s information, making it universally accessible and useful.16,17 Doctors Without Borders works towards their mission of saving lives and alleviating the suffering of people in danger by delivering medical care where it is needed by targeting the public to raise the awareness and funds necessary to deliver on their promise.18–20

A clinical research team’s strategy should draw upon both of these types of efforts. The strategy must be based on targeting institutions for funds as Doctors Without Borders does so that the research team has the resources to conduct studies, but the research must also be tailored to be accessible and useful to its field as Google does with their products. Research outcomes may be defined by the knowledge generated and the quality of the publications produced.21 At M-CHOIR, we implement various strategies to ensure we remain productive and contribute meaningful findings to science. These strategies are focused on constantly developing innovative research projects, establishing a clear vision for our projects, increasing the number of collaborations, and developing a diverse team with individuals of various expertise.

Adjusting to Change

Researchers aim to produce as many impactful findings as possible to generate knowledge. Thus, researchers must attract readers much like marketing attracts consumers to produce quality findings. The ability to target readers is often constrained by grant money much like non-profits are driven by donations. To entice readers, research groups must continuously adjust to the changing dynamic of healthcare. For example, as US healthcare moves progressively toward universal healthcare, new payment initiatives have emerged. One of these is the Bundled Payments initiative implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services.22 M-CHOIR identified this as an under-investigated yet important area of research and chose to focus resources on projects that can influence and direct future healthcare policy. Researching areas of heightened interest also imbues the group with a sense of urgency and motivation as others begin publishing on the same topic.

Vision

A clear vision establishes direction towards achieving a goal, even in times of uncertainty. Goleman cites visionary leadership as one of the emotional intelligence competencies necessary for effective leadership.23 A vision must be identified prior to constructing a strategy. As one article puts it, a vision is not the map, but rather the reason for creating a map.24 Without a vision, end goals become vague, and creating strategies to achieve these goals becomes difficult. Once a vision is in place, a strategy with pragmatic steps can be created (Figure 2). Wilson described a special care nursery where a seven-step strategy was developed to work towards a vision of improved teamwork resulting in happier employees providing better care.25 This strategy worked from an initial stage of determining the staff’s values, to realizing these values in practice and involved conducting workshops, analyzing the results, and reflecting and acting upon the analysis.25 Although this article does not explicitly discuss how to develop a vision for a team in research, the strategy outlined by Wilson may serve as a model.

Figure 2.

Using Strategies to Realize a Vision

Organizational Structure

Organizational structure is intimately tied to organizational strategy. In short, the strategy determines how information and production is coordinated and the organizational structure must accommodate this for the strategy to be successfully executed.26 One study analyzed the evolving structure and strategy of General Motors throughout the 20th century.27 During the great depression, General Motors differentiation strategy was replaced by an assembly line strategy. Assembly lines were introduced as a key component of the organization’s structure to reduce costs.27 Although the assembly line is an often noted example of organizational innovation during the Industrial Revolution, in more recent decades, disorganization and lack of communication in General Motors’ strategy led to structural disorganization and contributed to the subsequent decline of the automobile industry.27

In the context of clinical research, the members and roles of the team must be carefully considered and selected to fill necessary skill gaps. At M-CHOIR, we have a centralized model where the PI is involved on every project. Various positions impart expertise in clinical, academic, and statistical skills, and papers are written by teams as a collaborative effort combining their expertise. Today, M-CHOIR is a team of over 40 members, including faculty, research fellows, clinical residents, statisticians, research coordinators, research assistants, research associates, medical students, undergraduate students, and volunteers. Both the level of expertise and number of team members on a project will vary depending on the type research project. For example, a retrospective database study may only need a faculty member and a research associate, whereas a clinical trial may require faculty, coordinators, statisticians, and assistants.

Collaboration

Collaboration across different sectors and nations has become increasingly common. According to a report published by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), the number of publications with authors from multiple countries increased from 13% to 19% between 2003 and 2013.28 In 2016, M-CHOIR collaborated with Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan. Taiwan’s healthcare system is unique in that it has a government run, single-payer health insurance plan that covers over 97% of the population. Although this opened up exciting new research opportunities by applying a longitudinal population data for health services and outcomes assessment, it also revealed the lack of population statistics expertise within the research team. To fill this necessary skill gap, M-CHOIR recruited a statistician to assist in big data analysis which was needed to accomplish the population studies that the database made possible. Through this partnership and after acquiring a statistician, we were able to publish various papers, such as one analyzing the relationship between hospital and surgical volumes and the success of free flap surgery.29 Additionally, interdepartmental collaboration is sometimes necessary. This may involve consulting a research team in a different department about a database or developing a new project with a team in another department. For example, at M-CHOIR, we collaborated with a team in the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Michigan to perform a systematic review of nerve transfer and nerve repair for adult brachial plexus injury.30

Funding

When developing a business strategy, three key aspects need to be identified: funding, competition, and critical issues.31 For M-CHOIR, similar to other researchers in plastic and reconstructive surgery, funding comes from external organizations such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Plastic Surgery Foundation (PSF), the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand (AFSH) and industry funding.32,33 As is often espoused in healthcare, “No margin, no mission.” Additionally, funding is related to academic productivity. Therattil et al. found that plastic surgeons receiving a PSF grant had higher levels of academic productivity over time, indicated by a higher h-index.34 A large part of our focus is developing grant proposals to support the education of our team members and to conduct a myriad of projects in hopes of making each member a productive contributor to research.

The infrastructure for grant funding differs based on the competitiveness of each grant. At M-CHOIR, trainees commonly apply for funding from the AFSH and PSF, these grants are typically made for investigators beginning research. The fellows and residents are responsible for developing the grant in its entirety, with oversight from a coordinator and PI. Research assistants help with administrative materials. On the other hand, for more competitive funding, various research coordinators, associates, and statisticians work closely with the PI. In addition, collaboration is sometimes necessary to demonstrate the proposal can be successfully completed.

One strategy for developing ideas for projects and grant proposals is through a monthly journal round-up. Each month, research coordinators compile articles from high-profile journals that incorporate innovative concepts. These articles are then discussed and used to generate ideas for grants and new projects. Finally, we regularly assess what skills are missing from our team and hire new members to fill these gaps, or develop them through continuing education by attending conferences and lectures.

To obtain sufficient funding for research, the proposal must be clear and well thought-out. Every grant proposal should present a novel hypothesis or use innovative methodology. Our research group has previously described fundamental principles of writing a successful grant proposal. The steps to writing a successful grant include following directions, starting early, writing clearly and persuasively, making friends with the sponsored research office, thinking like a reviewer, and extensive proofreading.35

Learning through Failure

Failing to develop a successful business strategy can have catastrophic results. To prevent inevitable failure from a poor strategy, teams should foster positive attitudes and encourage improvement. Within M-CHOIR, failed projects are often evaluated as a team to determine where fatal error occurred and to reassess the study’s viability. In one case, this evaluation of failed projects resulted in a publication focused on strategies for solving problem areas in a study.36 Through meetings where the team reflects on a past research project, each member may improve their skill set by learning how to avoid setbacks in the future. Additional improvement efforts can be made through continuing education efforts. Research shows that workshops that encourage participant activity are more likely to improve professional practice and outcome than didactic sessions.37 The M-CHOIR style of team meetings is interactive and outcomes focused, rather than a unidirectional lecture. Moreover, after accumulating an extensive amount of knowledge on a study design, M-CHOIR often shares their insight with others in the scientific community.38–45 These unique pieces can help other teams learn from the experiences of others and create a sense of community among research teams worldwide.

Execution

Execution is the ability to effectively and successfully follow a strategy and can be defined as “a set of behaviors and techniques that companies need to master to have a competitive advantage.” Bossidy and Charan emphasize that execution must be built into an organization’s culture, goals, and strategy, in addition to the necessity for leaders to reflect critically and realistically on their efficiency and productivity.46 Realism and a sense of urgency are vital for efficient execution. When companies and organizations fail, it can be attributed to failed execution and poor strategy.47

Timelines and Realism

A lack of realism can lead to overconfidence and subsequent demoralization when unrealistic goals are not met.46 One of the most important aspects of realism is the ability to understand and improve upon both individual and collective weaknesses.46 Without understanding weaknesses, improvement stagnates.46 One way to overcome this is to embed improvement efforts into strategy. Furthermore, realistic timelines should be constructed and followed to reduce burnout. Realistic timelines are constructed with possible pitfalls in mind, and are adapted as challenges and distractions arise. However, they also imbue a sense of urgency for employees. The ability to adapt timelines becomes particularly important when aspects outside of the organization’s control need to be taken into account. An example of a realistic timeline for a prospective cohort study is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Research Project Timeline

Creating a Plan

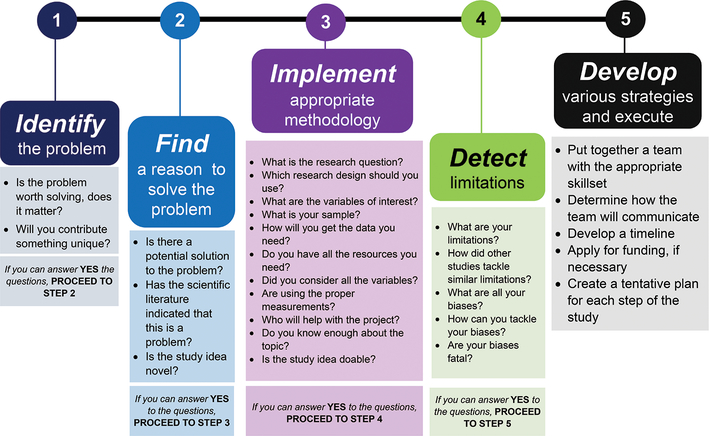

Before undertaking any research project, M-CHOIR creates a “first page” of an NIH grant, regardless of whether additional funding is needed (Figure 4). This “first page” answers the question of why the research is relevant to plastic surgeons, defines two to three aims o, proposes hypotheses, lists the rationale for why the aims are worth studying, defines variables of interest and the dataset, and lists two or three ways the topic will have impact. Figure 5 outlines our process behind determining the factors that go into a first page. This clarifies the goals of the project, highlights problematic areas, and can then be used to create a realistic timeline.

Figure 4.

First Page

Figure 5.

Developing a Study Idea

Accountability

Accountability is essential for keeping employees motivated and creating a sense of urgency. Effective accountability creates responsibility for an outcome rather than a set of tasks.48 In practice, this means that members are held accountable for the quality rather than the quantity of their manuscripts. Additionally, expectations, capability, measurement, and consequences should all be made clear.48 In other words, what should be achieved, what are the resources and skills available, how will “success” and “failure” be measured, and what will happen if the outcome is not achieved should all be defined. Within M-CHOIR, accountability is primarily established through weekly update email chains (Figure 6). Once a week, every member of the team must update all the other members on their progress on urgent, ongoing, and idle tasks through email. This creates open communication, transparency among members, and keeps progress highly visible. The PI then goes through the weekly updates, determining projects that are lagging or deadlines that have failed to have been met, and addresses these concerns individually. The weekly email updates also show each member’s workload and prioritization of their projects. This tempers frustrations from other team members when they feel as if progress has been slow, if they see that other, higher priority projects, such as NIH-funded population studies, are requiring more attention from their collaborators. Additionally, it helps the PI delegate tasks in a fair and effective manner by displaying each member’s workload in a concise manner.

Figure 6.

Structure of a Weekly Update

Execution in Practice

Google and Doctors Without Borders provide their own examples of effective tools for the execution of their respective strategies. To execute their strategy of fostering a culture of innovation, Google has an extra arm, Google Alphabet, that is not associated with the main company that is used for riskier, more innovative projects. Employees of Google Alphabet are encouraged to spend time on pet projects in addition to their regular tasks.49 Additionally, to execute their goal of driving towards digital priorities, Google watches market changes and focuses on consumer demands, leading to the creation of mobile applications for services such as Gmail and Google Drive.16 Doctors Without Borders, in their attempt to reach the public to maximize their impact has successfully leveraged social media. In 2010, they were able to put pressure on the US government to bring aid to Haiti through a tweet.50

Outcomes

Evaluating outcomes is vital for understanding success, discovering weaknesses, and working towards continual improvement (Figure 7). Both successful and failed methods can be evaluated for improvement. In the business world, success can be measured by revenue growth and rankings. Non-profit organizations also have quantifiable measures of success such as total contributions and charity scores. Surgery research teams can quantify success through the proportion and number of papers that are accepted for publication over a set time period and the citations derived from these publications to measure their impact.

Figure 7.

Cycle of Continuous Improvement

M-CHOIR emulates aspects of the Toyota model, particularly the concept of kaizen (改善), or continual improvement, to reflect upon each completed project.51 In cases of rejected manuscripts or failed studies, the study design and process is evaluated for flaws. Once these flaws are identified, they are presented to the entire team so that they are not repeated in future studies. M-CHOIR employs strategies such as conceptual models and root cause analysis to identify flaws in study designs.36 M-CHOIR used these strategies in conjunction to reflect upon a failed study into Dupuytren contractures.36 Root cause analysis was applied to identify three critical problems in the study: a lack of clinical data in the dataset, a lack of an impactful conclusion, and an overly broad research question. Conceptual models were then used to alter the experimental design to lead to a more impactful research question, and various other datasets were investigated for their appropriateness for the study. Through these strategies, a dead-end research project was revised into a study with potential. Additionally, manuscripts that are accepted for publication are rounded up each month and distributed to the team so that successful study designs and methods can be studied.

Conclusion

Successful research teams, similar to prosperous businesses and charitable organizations, define a set of strategies and ensure those strategies are executed in everyday practice. Effective strategies outline goals, can be contextualized within the team’s overall mission, and are realistic. These strategies can then be executed in a timely manner, leading to successful and impactful publications. Consistent evaluation of outcomes leads to continual improvement and increased efficiency, with the ultimate goals of life-long learning.

We recognize that the concepts discussed in this special topics article are tailored to our research group. Notwithstanding, these strategies can be applied to other research teams hoping to remain competitive in research. Additionally, we demonstrate how a team can derive their own strategies using various the concepts of prosperous businesses and charitable organizations. By adopting a similar framework, we hope that other research teams will be able to adopt some of our strategies to remain competitive in an ever-changing field.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The work was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (2 K24-AR053120-06) to Kevin C. Chung. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Murillo H, Reece EA, Snyderman R, Sung NS. Meeting the challenges facing clinical research: solutions proposed by leaders of medical specialty and clinical research societies. Acad Med. February 2006;81(2):107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyngaarden JB. The Clinical Investigator as an Endangered Species. B New York Acad Med. 1981;57(6):415–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sterbenz JM, Chung KC. The Affordable Care Act and Its Effects on Physician Leadership: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Qual Manag Health Care. Oct-Dec 2017;26(4):177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ductor L Does Co‐authorship Lead to Higher Academic Productivity? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 2015;77(3):385–407. [Google Scholar]

- 5.West MA, Borrill C, Dawson J, et al. The link between the management of employees and patient mortality in acute hospitals. Int J Hum Resour Man. December 2002;13(8):1299–1310. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. March 2014;90(1061):149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesth Scand. February 2009;53(2):143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edmondson A Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Admin Sci Quart. June 1999;44(2):350–383. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozlowski SWJ, Ilgen DR. Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychol Sci. December 2006:77–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks MA, Mathieu JE, Zaccaro SJ. A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Acad Manage Rev. July 2001;26(3):356–376. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilgen DR, Hollenbeck JR, Johnson M, Jundt D. Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:517–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denman SB. Social-Psychology - a Brief Introduction - Mcgrath,Je. Sociol Quart. 1965;6(3):298–299. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathieu JE, Gilson LL, Ruddy TM. Empowerment and team effectiveness: An empirical test of an integrated model. J Appl Psychol. January 2006;91(1):97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larkin R Using Outcomes to Measure Nonprofit Success. 2013; https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2013/07/02/using-outcomes-to-measure-nonprofit-success/. Accessed April 18, 2018.

- 15.Annual Filing Requirements for Nonprofits. 2018; https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools-resources/annual-filings. Accessed April 18, 2018.

- 16.Bloomberg J Google’s Three-Pronged Enterprise Strategy. Tech 2014; https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonbloomberg/2014/12/31/googles-three-pronged-enterprise-strategy/. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 17.https://www.google.com/about/our-company/. Accessed Aprill 11, 2018.

- 18.The MSF Association. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/about-us/msf-leadership/msf-association. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 19.Hertig A For Doctors Without Borders, Content Marketing Is a Matter of Life or Death. Brands 2015; https://contently.com/strategist/2015/01/23/for-doctors-without-borders-content-marketing-is-a-matter-of-life-or-death/. Accessed April 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirchoff KR,J Retargeting Revealed. E-Philanthropy 2013; http://www.nonprofitpro.com/article/doctors-without-borders-uses-remarketing-retargeting-extend-reach/all/. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 21.Duryea MH,M; Parfitt A Measuring the impact of research. 2007; http://facdent.hku.hk/docs/ResGlob2007.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 22.Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed August 25, 2017.

- 23.Goleman D Leadership that gets results. Harvard Bus Rev. Mar-Apr 2000;78(2):78-+. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basu E Vision Is Not The Roadmap, It’s The Reason For Having The Map In The First Place. Entrepreneurs 2013; https://www.forbes.com/sites/ericbasu/2013/04/29/vision-is-not-the-roadmap-its-the-reason-for-having-the-map-in-the-first-place/#2cb406907fbf. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 25.Wilson V Developing a vision for teamwork. Practice Development in Health Care. 2005;4(1):40–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miles RE, Snow CC, Books24×7 Inc. Organizational strategy, structure, and process. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press; 2003: http://www.books24×7.com/marc.asp?bookid=7347. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marx TG. y The impacts of business strategy on organizational structure. J Manag Hist. 2016;22(3):249–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witze A Research gets increasingly international. News 2016; https://www.nature.com/news/research-gets-increasingly-international-1.19198. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 29.Mahmoudi E, Lu Y, Chang SC, et al. Associations of Surgeon and Hospital Volumes with Outcome for Free Tissue Transfer by Using the National Taiwan Population Health Care Data from 2001 to 2012. Plast Reconstr Surg. September 2017;140(3):455e–465e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang LJS, Chang KWC, Chung KC. A Systematic Review of Nerve Transfer and Nerve Repair for the Treatment of Adult Upper Brachial Plexus Injury. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(2):417–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton JL, Foxcroft S, Moyo E, et al. Strategic planning in an academic radiation medicine program. Curr Oncol. December 2017;24(6):e518–e523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan QZ, Cohen JB, Baek Y, et al. Identifying Sources of Funding That Contribute to Scholastic Productivity in Academic Plastic Surgeons. Annals of plastic surgery. April 2018;80(4 Suppl 4):S214–s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson KE, Gastman B. Sources of federal funding in plastic and reconstructive surgery research. Plast Reconstr Surg. May 2014;133(5):1289–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Therattil PJ, Sood A, Chung S, Granick MS, Lee ES. Effect of Research Grant Funding on Academic Productivity in Plastic Surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2015;136(4S):162. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KC, Shauver MJ. Fundamental Principles of Writing a Successful Grant Proposal. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2008;33(4):566–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujihara Y, Saito T, Huetteman HE, Sterbenz JM, Chung KC. Learning from an Unsuccessful Study Idea: Reflection and Application of Innovative Techniques to Prevent Future Failures. Plast Reconstr Surg. April 2018;141(4):1056–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. September 1 1999;282(9):867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shauver MJ, Chung KC. A guide to qualitative research in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. September 2010;126(3):1089–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung KC, Burns PB, Kim HM. A Practical Guide to Meta-Analysis. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2006;31(10):1671–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung KC, Song JW, group Ws. A Guide on Organizing a Multicenter Clinical Trial: the WRIST study group. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010;126(2):515–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung KC, Burns PB. A guide to planning and executing a surgical randomized controlled trial. The Journal of hand surgery. March 2008;33(3):407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung KC. Clinical research in hand surgery. The Journal of hand surgery. January 2010;35(1):109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung KC, Kotsis SV. The Ethics of Clinical Research. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2011;36(2):308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns PB, Chung KC. Developing good clinical questions and finding the best evidence to answer those questions. Plast Reconstr Surg. August 2010;126(2):613–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swiatek PR, Chung KC, Mahmoudi E. Surgery and Research: A Practical Approach to Managing the Research Process. Plast Reconstr Surg. January 2016;137(1):361–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bossidy L, Charan R, Burck C. Execution : the discipline of getting things done. 1st ed. New York: Crown Business; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longenecker CO, Simonetti JL, Sharkey TW. Why organizations fail: the view from the front-line. Management Decision. 1999;37(6):503–513. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bregman P The Right Way to Hold People Accountable. Developing Employees 2016; https://hbr.org/2016/01/the-right-way-to-hold-people-accountable. Accessed April 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reeves M Google Couldn’t Survive with One Strategy. Strategy 2015; https://hbr.org/2015/08/google-couldnt-survive-with-one-strategy. Accessed April 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villarino E The power of a tweet: Doctors Without Borders’ success story. Funding Trends | Devex Interview 2011; https://www.devex.com/news/the-power-of-a-tweet-doctors-without-borders-success-story-76230. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- 51.Kaizen - Toyota Production System guide. 2013; http://blog.toyota.co.uk/kaizen-toyota-production-system. Accessed April 11, 2018.