Abstract

SUMMARY – Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a brain dysfunction caused by liver failure. Clinically, it can manifests as a wide spectrum of neurological or psychiatric abnormalities. This report presents a case of a 43-year-old male with HE and asymmetric kinetic, postural and resting tremor of upper extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed signal abnormalities in numerous areas. The patient underwent liver transplantation and six months after normalization of liver function, tremor as well as brain MRI abnormalities almost completely regressed. This case report presents the asymmetric and reversible kinetic, postural and resting tremor of upper extremities as part of the spectrum of neurological abnormalities in HE.

Key words: Hepatic encephalopathy, Tremor, Magnetic resonance imaging, Liver transplantation, Case reports

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a brain dysfunction caused by liver failure (1). In most cases, it is associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension or portal-systemic shunts, but brain dysfunction also occurs in acute liver failure. Rarely, HE is caused by the presence of congenital or acquired shunts resulting in portal-systemic bypass without hepatocellular disease (2). The most common causes of cirrhosis are alcoholic liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis, but other causes include drug-related hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cardiac or vascular diseases (right-sided heart failure, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis), metabolic disorders (hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency), or biliary diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis) (3). If the findings of medical examinations do not reveal the cause of liver scarring, this type of liver disease is called cryptogenic cirrhosis.

A common pathogenetic notion is that HE is caused by substances such as ammonia, which in normal circumstances are efficiently metabolized by the liver. These substances reach systemic circulation as a result of portal-systemic shunting or reduced hepatic clearance and produce deleterious effects on brain function (4).

Hepatic encephalopathy can manifest as a wide spectrum of neurological or psychiatric abnormalities ranging from subclinical alterations to coma (1). Neurological abnormalities may include extrapyramidal dysfunction, such as hypomimia, muscle rigidity, bradykinesia and hypokinesia. In patients with HE (pwHE), except for asterixis, which is actually negative myoclonus, parkinsonian-like tremor can also be seen (5, 6).

Although HE is a clinical condition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is useful for the diagnosis because it can show the accumulation of the substances normally metabolized in the liver (7). The most frequent MRI brain findings in pwHE show high signal intensity in the globus pallidus and midbrain on T1-weighted images (T1WI), which is thought to be a reflection of tissue manganese deposition. Other MRI techniques such as T2-weighted images (T2WI) and diffusion weighted imaging can identify abnormalities resulting from disturbances in cell volume homeostasis secondary to brain hyperammonemia.

The main goal in the treatment of pwHE is reduction of ammonia generated in the colon, and therefore the mainstay of therapy is administration of non-absorbable disaccharides and antibiotics, as well as nutrition modulation (1). Liver transplantation (LT) can be considered for patients with end-stage liver disease who have failed standard medical treatment (8). Clinical manifestations of HE, as well as MRI brain abnormalities can be partially or completely reversible with restoration of liver function after LT (7).

The following case report focuses on the pwHE with asymmetric kinetic, postural and resting tremor of upper extremities, not described to date, which along with MRI brain abnormalities regressed after LT.

Case Report

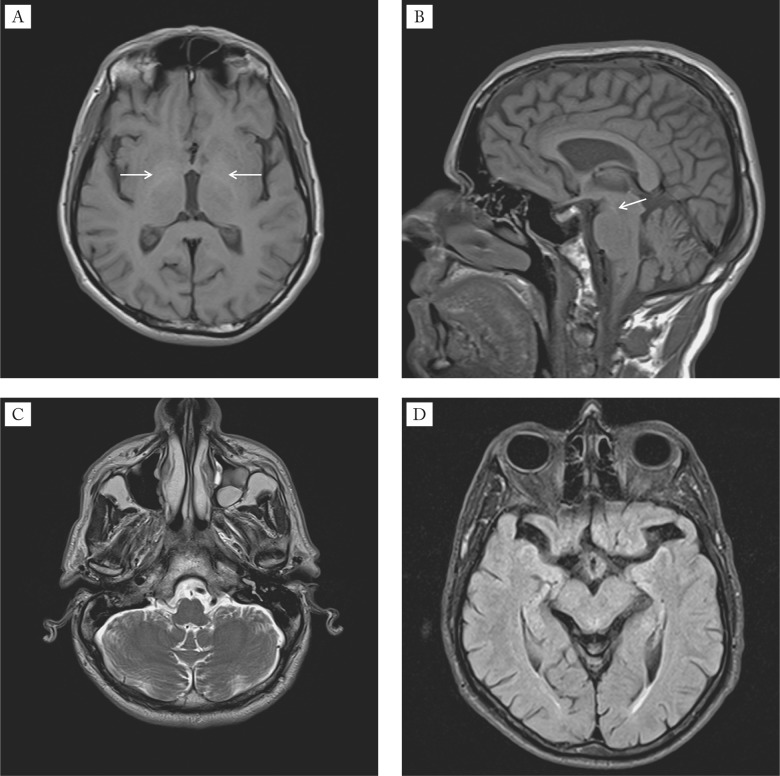

A 43-year-old male with cryptogenic cirrhosis underwent neurological and neuroradiological examinations due to the recent onset of tremor of upper extremities. Cirrhosis was diagnosed 3 years earlier after an episode of lethargy and confusion. Later on, the patient was repeatedly treated for severe HE precipitated with infection, and each time recovered a few days later. On physical examination, he had fetor hepaticus, slight yellow discoloration of the sclera and spider angiomata on the upper chest. The abdomen was soft and painless with no evidence of ascites and hepatomegaly, but with splenomegaly. On neurological examination, he had asymmetric (moderate left, mild right) kinetic, postural and resting tremor of upper extremities, cogwheel rigidity at the wrists, dysarthria, diffusely increased deep tendon reflexes, and bilateral extensor plantar response. His gait was normal with mild impairment in pivoting. Laboratory test results obtained at the time of examination were the following: white blood cell count 1.96x10.e9/L (normal 3.4-9.7x10.e9/L), red blood cell count 3.88x10.e12/L (normal 4.34-5.72x10.e12/L), hematocrit 0.342 L/L (normal 0.415-0.53 L/L), platelet count 36 x10e.9/L (normal 158-424x10e.9/L), international normalized ratio (INR) 1.26 (normal 0.8-1.12), total bilirubin 37.6 µmol/L (normal 3-20 µmol/L), aspartate aminotransferase 77 U/L (normal 11-38 U/L), alanine aminotransferase 48 U/L (normal 12-48 U/L), gamma-glutamyltransferase 59 U/L (normal 1-55 U/L), and ammonia 85.6 µmol/L (normal 18-72 µmol/L). Serum ceruloplasmin, serum copper and urinary copper excretions were within the normal range. The slit-lamp ophthalmologic examination did not reveal Kayser-Fleischer ring. The DaTscan was unremarkable. The electroencephalogram revealed mild, generalized slowing of the background rhythm. Performed on a 1.5 T unit, T1WI MRI demonstrated bilateral hyperintense signal in the globus pallidus and in the substantia nigra, whereas T2WI and fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI showed bilateral hyperintense signal in the dentate nucleus, crus cerebri and red nucleus, as well as in the periventricular white matter, corpus callosum and internal capsule (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Baseline MRI findings of the brain: (A) axial T1WI MRI demonstrates hyperintensity in the globi pallidi (arrows); (B) sagittal T1WI MRI demonstrates hyperintensity in the substantia nigra (arrow); (C) axial T2WI MRI shows hyperintensity in the nuclei dentati (arrows); (D) axial FLAIR MRI shows hyperintensity in the crura cerebri (arrows) and in the red nuclei (black arrowheads).

Regardless of the standard ammonia-lowering therapy used, the patient’s neurological status did not improve. He was put on the waiting list for LT, and nine months later, he underwent successful transplantation. Two months after LT, he noticed improvement of speech and tremor. Neurological examination performed six months after LT demonstrated mild kinetic and postural tremor of the left hand and diffusely increased deep tendon reflexes. The speech was normal, the plantar response was flexor, the cogwheel rigidity was absent, and pivoting was normal. Follow up MRI study on T1WI demonstrated almost complete regression of hyperintense signal in the globi pallidi and in the substantia nigra, as well as complete regression of hyperintense signal in the nuclei dentati, crura cerebri and red nuclei on T2WI and FLAIR (Fig. 2). There was also complete regression of hyperintense signal in the corpus callosum and partial regression in the internal capsules on T2WI and FLAIR.

Fig. 2.

Follow up brain MRI 6 months after liver transplantation: (A) axial T1WI MRI demonstrates almost complete regression of hyperintensity in the globi pallidi (arrows); (B) sagittal T1WI MRI depicts subtotal regression of hyperintensity in the substantia nigra (arrow); (C) axial T2WI MRI demonstrates regression of hyperintensity in the nuclei dentati; (D) axial FLAIR image shows regression of hyperintensity in the crura cerebri and in the red nuclei.

Discussion

Liver transplantation remains the only treatment option for pwHE whose condition has not improved on any other treatment. HE by itself is not considered an indication for LT unless associated with poor liver function. However, cases do occur where HE compromises the patient’s quality of life and cannot be improved despite maximal medical therapy and who may be LT candidates despite otherwise good liver status (1). In this pwHE, LT had a favorable effect on the disabling asymmetric tremor of upper extremities after six months. The good outcome also included improvement of dysarthria, plantar response, cogwheel rigidity and pivoting.

Tremor is defined as an involuntary and rhythmic movement of a body part that is produced by alternating contractions of reciprocally innervated muscles (9). Its etiology is highly diverse. Tremor can be a sign of different neurodegenerative diseases, as well as of inflammatory, endocrine, toxic and metabolic disturbances. In pwHE, parkinsonian-like tremor occasionally can be seen (5, 6), but the asymmetric kinetic, postural and resting tremor of upper extremities has never been documented. Otherwise, focal and asymmetric neurological signs in the course of HE have been poorly documented (10). Contrary to the perception-based belief, asymmetric neurological symptoms are not infrequent in metabolic diseases. Examples of inherited metabolic diseases with asymmetric neurological symptoms include dystonia in Segawa disease, Leigh disease, unilateral tremor in atypical forms of glutaric aciduria type I and Wilson disease (11, 12). The acquired metabolic disorder with frequent asymmetric neurological symptoms is hypoglycemia (13). Therefore, we think that asymmetric neurological symptoms in the course of HE should be paid more attention.

In pwHE, brain MRI abnormalities appear to be reversible in most cases after LT (7). In this pwHE, LT had a favorable effect on MRI abnormalities. Follow up brain MRI six months after LT demonstrated almost complete regression of hyperintense signal in the globi pallidi and in the substantia nigra on T1WI, as well as complete regression of hyperintense signal in the nuclei dentati, crura cerebri and red nuclei on T2WI and FLAIR. There was also complete regression of hyperintense signal in the corpus callosum and partial regression in the internal capsules on T2WI and FLAIR.

Although the exact pathophysiology of tremor is still incompletely understood, the progress has been made in mapping tremors to certain structures or pathways in the nervous system. Deuschl et al. identified peripheral mechanisms, as well as central oscillators involved in tremorogenesis (14). Two sets of central oscillators involved in tremorogenesis are of particular importance (15). One is the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit through the basal ganglia, the physiological task of which is integration of different muscle groups for complex movement programs. This loop also ensures that an ongoing movement program will not be terminated or disturbed by minor or irrelevant external influences. The other circuit involves the inferior olivary nucleus, red nucleus and dentate nucleus. This circuit’s main task is to fine-tune voluntary precision movements. Structural lesions affecting these circuits can cause tremor (16). The brain MRI of this pwHE showed signal abnormalities in numerous tremorogenic and non-tremorogenic structures, such as the basal ganglia, dentate nuclei, red nuclei, periventricular white matter, corpus callosum, internal capsules and crura cerebri.

In conclusion, this case report presents the pwHE with disabling asymmetric kinetic, postural and resting tremor of upper extremities, not described so far, which along with MRI abnormalities regressed after LT and liver function normalization. Asymmetric and reversible tremor of upper extremities should be considered as part of the spectrum of neurological abnormalities in pwHE.

References

- 1.Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic Encephalopathy in Chronic Liver Disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715–35. 10.1002/hep.27210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordoba J, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC, eds. Schiff‘s Diseases of the Liver. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003: p 595-623. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathews RE, Jr, McGuire BM, Estrada CA. Outpatient management of cirrhosis: a narrative review. South Med J. 2006;99:600–6. 10.1097/01.smj.0000220889.36995.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordoba J. Hepatic encephalopathy: from the pathogenesis to the new treatments –Review Article. ISRN Hepatology. 2014, Article ID 236268, 16 pages, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2014/236268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Adams RD, Foley JM. The neurological disorder associated with liver disease. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1953;32:198–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissenborn K, Bokemeyer M, Krause J, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with liver disease. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 3:S93–8. 10.1097/01.aids.0000192076.03443.6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso J, Córdoba J, Rovira A. Brain magnetic resonance in hepatic encephalopathy. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2014;35:136–52. 10.1053/j.sult.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray KF. Carithers Rl Jr. AASLD practice guidelines: evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1407–32. 10.1002/hep.20704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deuschl G, Bain P, Brin M, Ad Hoc Scientific Committee Consensus Statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Mov Disord. 1998;13:2–23. 10.1002/mds.870131303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadranel JF, Lebiez E, Di MV, Bernard B, El KS, Tourbah A, et al. Focal neurological signs in hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: an underestimated entity? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:515–8. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Cazorla A, Wolf IN, Hoffman GF. Neurological disease. In: Hoffman GF, ed. Inherited Metabolic Diseases: A Clinical Approach. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2010: p 127-60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huster D. Wilson disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:531–9. 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshino T, Meguro S, Soeda Y, et al. A case of hypoglycemic hemiparesis and literature review. Ups J Med Sci. 2012;117:347–51. 10.3109/03009734.2011.652748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deuschl G, Raethjen J, Lindemann M, et al. The pathophysiology of tremor. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:716–35. 10.1002/mus.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elble R. The pathophysiology of tremor. In: Watts RL, Koller WC, eds. Movement Disorders: Neurologic Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2004: p 481-92. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puschmann A, Wszolek ZK. Diagnosis and treatment of common forms of tremor. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:65–77. 10.1055/s-0031-1271312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]