Abstract

SUMMARY – Helicobacter (H.) pylori is the cause of one of the most common chronic bacterial infections in humans. Risk factors for the development of laryngeal cancer are cigarette smoke, alcohol, and human papillomavirus. Several papers report on H. pylori isolated in tooth plaque, saliva, middle ear and sinuses. Many articles describe the presence of H. pylori in laryngeal cancer cases, however, without noting the possible source of infection, i.e. stomach or oral cavity. The aim of this study was to determine which patients and to what extent simultaneously developed H. pylori colonization in the stomach and the larynx. Prospective examinations were performed in 51 patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. The study group included patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma histopathologically confirmed by two independent pathologists. The patients underwent fiber esophagogastroduodenoscopy with tumor tissue biopsy. Laryngeal and gastric biopsies were examined by histologic staining technique for histopathologic detection of H. pylori and with DNA analyses using the standardized fluorescent ABI Helicobacter plus-minus PCR assay. Laryngeal carcinoma patients showed positive H. pylori test results simultaneously in the laryngeal and stomach areas, implying H. pylori transmission from the stomach to the laryngeal area. In addition, H. pylori positive test results along with negative H. pylori results in the stomach region were also recorded, suggesting a possible bacteria migration from the oral cavity. In conclusion, H. pylori was found in the area of laryngeal carcinoma, and its migration appeared likely to occur both upwards (from the stomach to the mouth) and downwards (from the oral cavity to the stomach).

Key words: Helicobacter pylori; Bacterial infections; Laryngeal neoplasms; Smoking; Papillomaviridae; Endoscopy, digestive system; Stomach

Introduction

Helicobacter (H.) pylori is the cause of one of the most common bacterial infections in human population, present all over the world. The incidence of H. pylori infection may hardly be directly established, as the acute infection has few to none characteristic symptoms. This is why the literature merely cites results on the prevalence of H. pylori infection. The worldwide prevalence of H. pylori infection is around 50%, increasing with patient age. In developed countries, infections at an older age (above 50) rise up to 50%. In developing countries, the prevalence in elderly patients may be even up to 90% (1). The most frequent is laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 95% of all laryngeal cancers. It develops between the fifth and seventh decade of life and peaks in the sixties, while the incidence is lower than 1% in the population below 30. Male population suffers from laryngeal cancer 8 to 12 times more frequently than females (2, 3). Laryngeal cancer is the second most common carcinoma of the head and neck, and the eleventh most frequent carcinoma ever (4). Risk factors for the development of laryngeal cancer are cigarette smoke, alcohol, and human papillomavirus (4-6). Several papers report on H. pylori isolated in tooth plaque, saliva, middle ear, and sinuses (7-10). Association between H. pylori infection and carcinoma of the larynx has been described by Zhou et al. (11). Many articles describe the presence of H. pylori in laryngeal cancer cases, however, without mentioning the possible source of infection, i.e. stomach or oral cavity. In our study, we examined gastric mucosa in patients with laryngeal carcinoma, in an attempt to find out which patients and to what extent simultaneously developed H. pylori colonization in the stomach and the larynx.

Patients and Methods

Prospective examinations were performed at the Department of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery and Department of Internal Diseases, Dr Josip Benčević General Hospital from Slavonski Brod. Testing was conducted in the period of two years. The research was approved by Dr Josip Benčević General Hospital Ethics Committee and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek. The research involved 51 patients with laryngeal SCC. Excluded from the study were subjects diagnosed with and treated for H. pylori infection by H2 blockers, antacids or proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics over four weeks (data obtained from history questionnaires). The patients were informed on the methods and purpose of the research, as well as on the fact that the tissue sampling methods might cause discomfort and complications. All patients signed the informed consent form for inclusion in the study. Study group included patients with laryngeal SCC verified histopathologically by two independent pathologists. The patients underwent fiber esophagogastroduodenoscopy using the GIF Q 140 gastroscope, which provided local test results for the larynx and the stomach. During esophagogastroduodenoscopy, biopsies were performed including two stomach antrum samples and two stomach corpus samples. Part of antrum and corpus biopsies were examined by histologic staining technique for histopathologic detection of H. pylori, and the other part were incorporated in paraffin blocks, whereupon the H. pylori gene expression was determined using deparaffinization and DNA isolation by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). During general endotracheal anesthesia, patients with verified laryngeal cancer were surgically treated by removing the entire tumor tissue (by partial or total laryngectomy).

After the operation, a number of tumor tissue biopsies were examined by histologic staining for histopathologic detection of H. pylori, and the others were incorporated in paraffin blocks, whereupon the H. pylori gene expression was determined using deparaffinization and DNA isolation by PCR method. The eluates with potential Helicobacter DNA were analyzed using the standardized fluorescent ABI Helicobacter plus-minus PCR assay. The presence of bacteria would be proven using the highly specific primers that were partially complementary to the H. pylori genome. If any of the patient’s stomach samples proved positive for H. pylori, the patient would be considered H. pylori positive.

Statistics

The McNemar test (χ2-test for dependent samples) was used to examine differences between positive test results obtained by using the two different methods. Statistical analysis was conducted on a PC using the Statistica 6.0 software.

Results

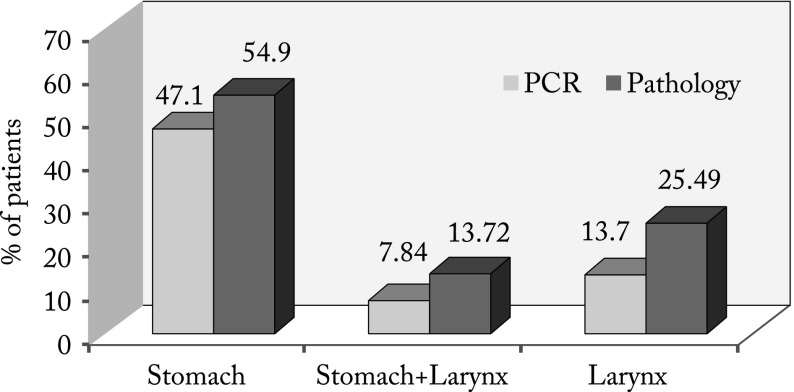

The results of our study showed the patients suffering from laryngeal carcinoma were generally male individuals aged ≥50. Distribution of stomach histopathology results (normal, acute gastritis, chronic gastritis) was equal in patients aged <50 and >50. There was no statistically significant correlation between stomach histopathology test results and age of patients that developed laryngeal tumor (Table 1). The rate of H. pylori stomach and larynx infections, as well as the incidence of laryngeal tumor were higher in patients aged ≥50. There was no statistically significant correlation between bacteriological test results and age of patients that developed laryngeal tumor (Table 2). Patients who developed laryngeal carcinoma most frequently had chronic gastritis (62.7%). The number of positive H. pylori test results did not differ statistically significantly between stomach tissue and larynx tumor tissue according to stomach histopathology results irrespective of the biochemical method used. However, the highest number of positive H. pylori results was recorded by the PCR method in patients with laryngeal tumors that had normal stomach test results (25.0%) (Table 3). Positive H. pylori test results of larynx tissue using the PCR method in patients with laryngeal tumor were found in 7/51 (13.72%) patients, whereas the results obtained by histopathology testing for H. pylori in laryngeal tumors were positive in 13/51 (25.49%) patients. The results of stomach testing by PCR method showed the presence of H. pylori in 24/51 (47.05%) patients, while the histopathology testing showed it in 28/51 (54.90%) patients. The simultaneous presence of positive H. pylori test results in both the stomach and the larynx was verified by the PCR method in 4/51 (7.84%) patients and by histopathology in 7/51 (13.72%) patients (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Table 1. Distribution according to age and stomach histopathology.

| Gastric histopathology finding | Age £50 (years) n (%) |

Age >50 (years) n (%) |

Total n (% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 2 (22.2) | 6 (14.3) | 8 (15.7) |

| Acute gastritis | 2 (22.2) | 9 (21.4) | 11 (21.6) |

| Chronic gastritis | 5 (55.6) | 27 (64.3) | 32 (62.7) |

| Total | 9 (100.0) | 42 (100.0) | 51 (100.0) |

χ2-test: χ2=0.3898, s.s=2, p=0.8229

Table 2. Distribution of Helicobacter pylori positive test results according to patient age.

| Biochemical methods – positive finding | Age £50 (years) N=42 |

Age >50 (years) N=42 |

Statistical significance* |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR – stomach | 5 (55.6%) | 19 (45.2%) | p=0.5736 |

| PCR – larynx | 1 (11.1%) | 6 (14.3%) | p=0.8017 |

| Histopathology – stomach | 6 (66.7%) | 22 (52.4%) | p=0.4344 |

| Histopathology – larynx | 1 (11.1%) | 12 (28.6%) | p=0.2754 |

*χ2-test; PCR = polymerase chain reaction

Table 3. Relation between stomach biochemical and histopathology test results in patients that developed laryngeal cancer.

| Biochemical method – positive test results | Histopathology test result – stomach | Statistical significance* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal N=8 |

Acute gastritis N=11 |

Chronic gastritis N=32 |

||

| PCR – stomach (N=24) | 4 (50.0%) | 6 (54.6%) | 14 (43.8%) | p=0.8123 |

| PCR – larynx (N=7) |

2 (25.0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (9.4%) | p=0.4596 |

| Histopathology – stomach (N=28) | 4 (50.0%) | 6 (54.6%) | 18 (56.2%) | p=0.9504 |

| Histopathology – larynx (N=13) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (18.2%) | 10 (31.2%) | p=0.4541 |

*χ2-test; PCR = polymerase chain reaction

Table 4. Distribution of the presence of Helicobacter pylori according to region (N=51).

| Biochemical method – positive test results | Stomach n (%) |

Stomach + Larynx n (%) |

Larynx n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | 24 (47.10) | 4 (7.84) | 7 (13.7) |

| Histopathology | 28 (54.90) | 7 (13.72) | 13 (25.49) |

PCR = polymerase chain reaction

Fig. 1.

Number of positive test results: stomach, stomach + larynx, and larynx by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and histopathology methods.

Discussion

The above premises could result in a conclusion that the patients that developed laryngeal tumor were predominantly chronic gastritis patients with the H. pylori-infected stomach, and that the infection reservoir was the stomach (given the fact that H. pylori was found in 47.05% and 54.90% of patients using the PCR and histopathology methods, respectively). In all stomach histopathology test results, H. pylori was found in the larynx region, but the infection was most frequently found in patients with normal stomach PCR results (2/8; 25.0%) and in patients with chronic gastritis in which the histopathology testing was performed (10/32; 31.2%).

Given the fact that 67.2% of the laryngeal cancer patients examined were found to have chronic gastritis and that the PCR method was best to detect positive result for H. pylori in such laryngeal cancer patients that had normal stomach test results, our finding might support the theory by Zhannat et al., according to which gastroesophageal reflux with H. pylori infection is protective against development of laryngeal carcinoma (12). As the laryngeal cancer patients predominantly had chronic gastritis, we may well suppose that these patients also had laryngopharyngeal reflux and that the presence of H. pylori infection had led to corporal gastritis with reduced parietal cell activity and reduced acid secretion. The PCR method proved the absence of H. pylori bacteria in the healthy larynx mucous lining (13). It is supposed that H. pylori might colonize the damaged laryngeal mucous lining and that its reservoir is the stomach; however, given the H. pylori presence in laryngeal tumor patients that had negative stomach test results (three and six patients using the PCR and Giemsa methods, respectively), there is also room for a theory that H. pylori may migrate down from the oral cavity to the laryngeal region (10). There is also a theory that H. pylori is transmitted through oro-oral, gastro-oral and feco-oral paths (14, 15).

Our study showed various results depending on the method used (PCR or histopathology), which might be explained by 90% sensitivity and specificity of the histologic process of H. pylori identification. To date, no routine histologic method exists to differentiate H. pylori coccoid forms from other cocci present in the sample (i.e. false-positive test results) (16, 17).

Conclusion

Laryngeal carcinoma patients display positive H. pylori test results simultaneously in the laryngeal and stomach regions. This implies transmission of H. pylori from the stomach to the larynx region. Also, a number of H. pylori positive test results along with negative H. pylori results in the stomach region are reported, which implies a possible bacterial migration from the oral cavity. Accordingly, it may be concluded that H. pylori is indeed found in the laryngeal carcinoma region, and that its migration is likely to occur both upwards (from the stomach to the mouth) and downwards (from the oral cavity to the stomach).

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by Dr Josip Benčević General Hospital from Slavonski Brod, Croatia.

References

- 1.Heatley RV. The Helicobacter pylori Handbook. New Jersey: Blackwell Science; 1996: p. 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes L, Gnepp DR. Disease of the larynx, hypopharynx and oesophagus. In: Barnes L., ed. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1985: p. 193-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudolph E, Dyekhoff G, Becher H. Effects of tumor stage, comorbidity and therapy on survival of laryngeal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:165–79. 10.1007/s00405-010-1395-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu EA, Kim YJ. Laryngeal cancer: diagnosis and preoperative work-up. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41:673–95. 10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudolph E, Dyekhoff G, Becher H. Effects of tumour stage, comorbidity and therapy on survival of laryngeal cancer patients: a systematic review and a meta analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:165–79. 10.1007/s00405-010-1395-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann JL, Cohen S, Evjen AN. Human papillomavirus in early laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1531–7. 10.1002/lary.20509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudhoff H, Rajagopal S, Baguley DM. A critical evaluation of the evidence on a causal relationship between Helicobacter pylori and otitis media with effusion. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:905–11. 10.1017/S0022215107000989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdek A, Cirak MY, Samim E. A possible role of Helicobacter pylori in chronic rhinosinusitis: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:679–82. 10.1097/00005537-200304000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen AM, Engstrand L, Genta RM, Graham DY, El-Zaatavi FA. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:783–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madinier IM, Fosse TM, Monteil RA. Oral carriage of Helicobacter pylori: a review. J Periodontol. 1997;68:2–6. 10.1902/jop.1997.68.1.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J, Zhang D, Yang Y, Zhou L, Tao L. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and carcinoma of the larynx or pharynx. Head Neck. 2016;38:E2291–6. 10.1002/hed.24214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhannat Z. Nurgalieva, Graham DY, Dahlstrom KR, Wei Q, Sturgis EM. A pilot study of Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of laryngopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2005;27:22–7. 10.1002/hed.20108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pajić-Penavić I, Danić D, Maslovara S, Gall-Trošelj K. Absence of Helicobacter pylori in healthy laryngeal mucosa. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:196–9. 10.1017/S0022215111002799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Queralt N, Bartolomé R, Araujo R. Detection of H. pylori DNA in human faeces and water with different levels of faecal pollution in the north-east of Spain. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:889–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02523.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson CL, Owen RJ, Said B, Lai S, Lee JV, Surman-Lee S, et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori by PCR but not culture in water and biofilm samples from drinking water distribution system in England. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:690–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02360.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akbayir N, Basak T, Seven H, Sungun A, Erdem L. Investigation of Helicobacter pylori colonization in laryngeal neoplasia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:170–2. 10.1007/s00405-004-0794-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burduk PK. Association between infection of virulence cagA gene Helicobacter pylori and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:584–91. 10.12659/MSM.889011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]