Abstract

SUMMARY – The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in Slovenia. We aimed to explore the prevalence itself, comparison among demographic groups and potential correlations. Data were collected based on the validated standardized Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (N=605). Most participants had sexual intercourse with one partner (n=523), and the majority of sexual relationships were heterosexual (n=584). University educated subjects had the highest claims of arousal, followed by those with master/doctoral degrees and college educated ones. The lowest level was expressed by subjects with elementary school. The youngest subjects (18-23 years) expressed the highest levels of desire and arousal, followed by the 24-29 age group. The 42-47 age group reported higher levels of lubrication and orgasm. The claim of satisfaction was highest in the 24-29 age group, while the pain was highest in the 42-47 age group. Strong correlation was found between the claims of desire and arousal (r=0.585), arousal and lubrication (r=0.879), lubrication and pain (r=0.856), orgasm and lubrication (r=0.856), satisfaction and orgasm (r=0.782), and pain and arousal (r=0.776) (p<0.001). We identified a 31% prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in Slovenia.

Key words: Orgasm; Slovenia; Coitus; Arousal; Lubrication; Pain; Sexual dysfunctions, psychological; Sexual dysfunctions, physiological

Introduction

In general, sexual dysfunction is defined as dyspareunia (1), as well as the absence of sexual desire, arousal, and stages of orgasm. Several studies have focused on different factors of influence that, according to the authors, could contribute to the incidence of female sexual dysfunction (FSD). The influencing factors might be physiological, psychological, negative experiences in relationships, low levels of happiness and overall well-being, emotional distress, sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorder, orgasmic disorder, sexual pain disorders, beliefs, past and present experiences/relationships, lifestyle, and other mood disorders (2-32). Investigations have also focused on linkages between changes in sexual arousal and menopause. Moreover, typical vaginal symptoms such as dryness discomfort are associated with decreased desire due to progressive chronologic aging (2). FSD traditionally includes sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorders, and sexual pain disorders during and/or after sexual intercourse (15, 16, 32). Authors have indicated that this problem remains uninvestigated (33). A high prevalence of FSD predicts lower/poorer female sexual functioning (34). It differs in various age groups and achieves high prevalence in more mature ages and relationships (35-37).

Most epidemiological studies indicate the prevalence of FSD at 37%-40% (38, 39), e.g., 25%-63% in the American population, or up to 30% in the Asian area (Hong Kong, China, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore) (40). In 1992, the National Health and Social Life Survey estimated the prevalence of FSD at 43% (14). Another study involving men and women (N=27,500) aged from 40 to 80 years indicated that 39% of sexually active women reported sexual activity disorders (40). The common denominator of most studies is a decrease in sexual desire followed by orgasmic dysfunction (41).

In relation to FSD, many researchers have used the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). The FSFI was designed to be an assessment instrument in clinical trials addressing the multidimensional nature of female sexual function (14). However, the measures have been criticized for their biased results for sexually inactive samples (42). Some authors argued that measuring sexual desire with the FSFI might be particularly problematic, contending that there is long-standing dissatisfaction with outdated models of female sexual desire (39). The relevance of the study based on FSFI is focused on acquiring relevant data because in Slovenia, information on the prevalence of FSD does not exist.

Materials and Methods

Ethical permission for the cross-national survey was obtained from the Slovenian Ethics Committee, and investigations were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles. All the participants gave a written informed consent before the study. The cross-national and sectional prevalence study started in July 2015 and was concluded in December 2015. Four clinical institutions in three different geographical locations in Slovenia were involved. We intentionally selected one clinical institution in the eastern, two in the central, and one in the western parts of Slovenia.

We used a validated standardized FSFI questionnaire (14). In every clinical institution, we distributed 250 questionnaires, with the exception of the central part of Slovenia, where we distributed 500 questionnaires (two in each clinical institution). The recruitment process was based on the following inclusion conditions: (a) adulthood (age ≥18 years); (b) physician’s verbal explanation; and (c) personal acceptance and return of the questionnaire understood as consent.

Out of the 1000 questionnaires, 623 were returned. Three hundred and twenty-seven questionnaires were fully and 257 partially completed. On statistical analysis, we included all partially completed questionnaires (with the exception of some missing demographic data and data in relation to endometriosis, all FSFI claims were entirely completed). We did not include female participants with mental (n=11; 1.8%) and sexual (n=7; 1.1%) disorders. The final sample included 605 female participants; the realization of the sample was 60.5%. The Cronbach alpha coefficient showed an appropriate internal consistency for each claim of FSFI questionnaire (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) (14) (Table 1).

Table 1. Internal consistency for claims.

| Claim | Questions | % | (α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desire | 1,2 | 1-5 | 0.856 |

| Arousal | 3, 4, 5, 6 | 0-5 | 0.950 |

| Lubrication | 7, 8, 9,10 | 0-5 | 0.961 |

| Orgasm | 11, 12, 13 | 0-5 | 0.934 |

| Satisfaction | 14, 15, 16 | 0 (or 1)-5 | 0.897 |

| Pain | 17,18,19 | 0 (or 1)-5 | 0.977 |

| All terms | 0.973 |

All participants were asked about their demographic variables including pregnancy and number of children, presence of endometriosis and menopause, number of sexual partners and sexual orientation, and the six major dimensions of female sexual function (desire, subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) in the previous four weeks. For FSFI, we used a validated questionnaire with 19 multiple-choice questions on a 5- or 6-point Likert scale (14). Domain scores were calculated by summing responses to items in each domain, then scaling this total with a multiplier that constrains all domains to the same range. Linguistic validation of the questionnaire was performed based on translation from English to Slovenian language and vice versa. Cultural validation was not required, based on the constant cultural proportion and the lack of cultural diversity in Slovenia.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 17.0 statistical software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk test were applied to evaluate whether values had a gaussian distribution to choose between parametric and nonparametric statistical tests. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk test on six claims of FSFI showed a non-normal distribution. Based on this finding, we used a non-parametric statistical analysis by use of Pearson correlation coefficient and χ2-test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The sample consisted of the following age groups: 30-35 (n=122; 20.2%), 24-29 (n=118; 19.5%), 36-41 (n=90; 14.9%) and 48-53 (n=69; 11.4%). Other groups are shown in Table 2. Based on Pearson coefficient, we found no positive correlations (see Table 8).

Table 2. Age groups (N=605).

| Age (years) | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| 18-23 | 62 | 10.2 |

| 24-29 | 118 | 19.5 |

| 30-35 | 122 | 20.2 |

| 36-41 | 90 | 14.9 |

| 42-47 | 66 | 10.9 |

| 48-53 | 69 | 11.4 |

| 54-59 | 44 | 7.3 |

| 60-65 | 26 | 4.3 |

| ≥66 | 8 | 1.3 |

f = frequency

Table 8. Correlations between independent variables and claims.

| Education | Pregnancy | Menopause | No. of children | Endometriosis | Sexual orientation | Sexual intercourse | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESIRE | Frequency | 0.07 | -0.006 | -0.236** | -0.153** | 0.012 | -0.032 | -0.129** |

| Level | 0.098* | 0.042 | -0.173** | -0.177** | 0.008 | -0.047 | -0.191** | |

| AROUSAL | Frequency | 0.215** | -0.015 | -0.176** | -0.088* | -0.002 | -0.06 | -0.271** |

| Level | 0.167** | -0.038 | -0.148** | -0.065 | 0.015 | -0.016 | -0.328** | |

| Confidence | 0.157** | 0 | -0.154** | -0.093* | 0.005 | -0.028 | -0.340** | |

| Satisfaction | 0.181** | -0.035 | -0.144** | -0.062 | 0.003 | -0.015 | -0.311** | |

| LUBRICATION | Frequency | 0.143** | -0.038 | -0.167** | -0.093* | -0.006 | -0.028 | -0.315** |

| Difficulty | 0.083* | -0.032 | -0.112** | -0.018 | 0.005 | -0.005 | -0.361** | |

| Frequency of maintaining | 0.175** | -0.018 | -0.148** | -0.057 | -0.008 | -0.024 | -0.319** | |

| Difficulty in orgasm | 0.098* | -0.03 | -0.093* | -0.005 | -0.011 | 0.005 | -0.366** | |

| ORGASM | Frequency | 0.196** | -0.006 | -0.097* | 0.032 | 0.041 | -0.022 | -0.232** |

| Difficulty | 0.124** | -0.018 | -0.056 | 0.023 | 0.009 | 0.022 | -0.328** | |

| Satisfaction | 0.113** | -0.012 | -0.049 | 0.02 | 0.029 | -0.044 | -0.326** | |

| SATISFACTION | With amount of closeness | 0.117** | 0.001 | -0.068 | -0.058 | 0.01 | -0.026 | -0.407** |

| With sexual relationship | 0.084* | 0 | -0.068 | -0.032 | 0.019 | -0.014 | -0.380** | |

| With overall sex life | 0.163** | 0.007 | -0.099* | -0.027 | 0.018 | -0.036 | -0.195** | |

| PAIN | With frequency during penetration | 0.093* | -0.061 | -0.089* | 0.009 | -0.017 | -0.004 | -0.394** |

| Frequency following penetration | 0.07 | -0.043 | -0.101* | -0.009 | -0.01 | -0.017 | -0.405** | |

| Intensity during or following penetration | 0.090* | -0.035 | -0.107** | -0.016 | 0.002 | -0.004 | -0.398** |

*p<0.005; **p<0.001

The youngest subjects (age 18-23) expressed the highest levels of desire and arousal, followed by the 24-29 age group. The 42-47 age group reported the highest levels of lubrication and orgasm. The claim of satisfaction and pain was highest in the 24-29 and 42-47 age group, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Estimation of claims according to age groups.

| Age group (years) | Desire | Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasm | Satisfaction | Pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-23 | M | 4.11 | 4.50 | 4.99 | 4.37 | 4.85 | 5.12 |

| SD | 1.07 | 1.29 | 1.43 | 1.66 | 1.44 | 1.61 | |

| 24-29 | M | 3.95 | 4.49 | 5.12 | 4.69 | 5.05 | 5.26 |

| SD | 0.90 | 1.28 | 1.42 | 1.61 | 1.16 | 1.45 | |

| 30-35 | M | 3.68 | 4.07 | 4.69 | 4.43 | 4.58 | 4.67 |

| SD | 1.08 | 1.72 | 2.01 | 1.96 | 1.72 | 2.12 | |

| 36-41 | M | 3.61 | 4.37 | 4.86 | 4.65 | 4.69 | 5.12 |

| SD | 0.98 | 1.61 | 1.76 | 1.80 | 1.51 | 1.82 | |

| 42-47 | M | 3.66 | 4.26 | 5.13 | 4.83 | 4.97 | 5.34 |

| SD | 1.01 | 1.50 | 1.46 | 1.53 | 1.33 | 1.55 | |

| 48-53 | M | 2.99 | 3.66 | 4.46 | 4.17 | 4.50 | 4.97 |

| SD | 1.15 | 1.62 | 1.81 | 1.87 | 1.52 | 1.78 | |

| 54-59 | M | 3.13 | 3.61 | 4.06 | 4.41 | 4.79 | 4.90 |

| SD | 1.20 | 1.61 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.32 | 1.67 | |

| 60-65 | M | 2.79 | 2.79 | 3.29 | 3.43 | 3.55 | 3.88 |

| SD | 1.18 | 1.76 | 2.13 | 2.18 | 1.91 | 2.42 | |

| ≥66 | M | 2.10 | 1.56 | 1.74 | 2.33 | 4.10 | 2.13 |

| SD | 0.99 | 1.68 | 2.34 | 2.61 | 1.68 | 2.55 | |

| Total | M | 3.60 | 4.11 | 4.73 | 4.46 | 4.72 | 4.96 |

| SD | 1.11 | 1.60 | 1.78 | 1.81 | 1.50 | 1.84 | |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

M = mean; SD = standard deviation; p = level of statistical significance

Concerning the level of education, study subjects had completed elementary school (n=30; 0.3%), secondary school (n=275; 45.5%), professional college (n=53; 8.8%), college (n=73; 12.1%), university (n=139; 23%), and master/doctoral degree (n=33; 5.5). Two (0.3%) of the respondents did not state their education level. The claim of arousal and orgasm was best estimated by university educated subjects, followed by those with master/doctoral degree and college. The lowest level was expressed by subjects with elementary school (Table 4).

Table 4. Level of education.

| Education | Arousal | Orgasm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elementary school | M | 3.39 | 3.98 |

| SD | 1.45 | 1.79 | |

| Secondary school | M | 3.90 | 4.24 |

| SD | 1.66 | 1.88 | |

| Professional college | M | 4.03 | 4.39 |

| SD | 1.61 | 1.79 | |

| College | M | 4.27 | 4.58 |

| SD | 1.52 | 1.76 | |

| University | M | 4.52 | 4.84 |

| SD | 1.47 | 1.65 | |

| Master/doctoral degree | M | 4.38 | 4.75 |

| SD | 1.58 | 1.74 | |

| Missing | M | 6.00 | 6.00 |

| SD | |||

| Total | M | 4.11 | 4.46 |

| SD | 1.60 | 1.81 | |

| p | 0.001 | 0.035 |

M = mean; SD = standard deviation; p = level of statistical significance

Most of the study participants were not pregnant (n=491; 81.2%). Others were pregnant in the 1st (n=34; 5.6%), 2nd (n=36; 6%) and 3rd trimester (n=37; 6.1%). Three (0.5%) respondents gave birth less than six weeks after the study (p=0.000; χ2=620.045; M=1.36; SD=0.89). Four (0.7%) respondents did not provide their pregnancy status. Based on the Pearson correlation coefficient, we did not find positive correlations with claims (see Table 8). Most of the participants did not have children (n=225; 37.2%), 147 (24.3%) had one child, 198 (32.7%) had two children, and 35 (5.8%) had three or more children (p=0.000; χ2=140.897; M=2.08; SD=0.96) (Table 5). Based on the Pearson correlation coefficient, we did not find positive correlations with claims (see Table 8).

Table 5. Number of pregnancy and children in the sample.

| Pregnancy | f | % | Children | f | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 491 | 81.2 | None | 225 | 37.2 |

| 1st trimester | 34 | 5.6 | One | 147 | 24.3 |

| 2nd trimester | 36 | 6.0 | Two | 198 | 32.7 |

| 3rd trimester | 37 | 6.1 | Three or more | 35 | 5.8 |

| Delivery (within less than six weeks) | 3 | 0.5 | |||

| Missing | 4 | 0.7 | |||

| Total | 605 | 100 | 605 | 100 |

f = frequency

Menopause was not detected in 503 (83.1%) participants. The sample included eight (1.3%) menopausal women on hormone replacement therapy and 85 (14%) menopausal women without hormone replacement therapy (p=0.000; χ2=1115.613; M=1.16; SD=0.44).

Most of the participants were free from endometriosis (n=576; 95.2%). Fourteen (2.3%) women were diagnosed with endometriosis and had undergone one surgical therapy (n=14; 2.3%), while another four (0.7%) had undergone additional surgical therapies. Four (0.7%) women had not been involved in any surgical procedure. Seven (1.2%) participants did not answer this part of the questionnaire (p=0.000; χ2=2192, 289; M=1.04; SD=0.34). Based on the Pearson correlation coefficient, we did not find positive correlations between menopause, endometriosis, and claims from the questionnaire (see Table 8).

Most of the respondents had sexual intercourse with one partner (n=535; 86.4%). The rest of the respondents were involved in sexual intercourse with two (n=11; 1.8%) and three (n=3; 0.5%) different partners. Twenty-three (3.8%) respondents reported no sexual activity (Table 6). Based on the Pearson coefficient, we did not find positive correlations with these claims (see Table 8).

Table 6. Number of sexual partners (N=619).

| Sexual partners | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| One partner | 535 | 86.4 |

| Two different partners | 11 | 1.8 |

| Three different partners | 3 | 0.5 |

| No sexual intercourse | 23 | 3.8 |

| Missing | 45 | 7.4 |

| Total | 605 | 100 |

p=0.000; χ2=1714.417; M=1.12; SD=0.86

p = level of significance; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; f = frequency

Most of the sexual relationships were heterosexual (n=584; 96.5%). A small proportion were bisexual (n=4; 0.7%) and homosexual (n=2; 0.3%) (Table 7). Based on the Pearson correlation coefficient, we did not find positive correlations with these claims (Table 8).

Table 7. Sexual relationship (N=604).

| Sexual relationship | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | 584 | 96.5 |

| Homosexual | 2 | 0.3 |

| Bisexual | 4 | 0.7 |

| Missing | 15 | 2.7 |

| Total | 605 | 100 |

p=0.000; x2=1714.417; M=0.99; SD=0.25

p = level of significance; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; f = frequency

The respondents used different methods of contraception. It should be noted that the majority (n=304; 50.2%) did not use any of the contraception methods listed in the questionnaire. We should note that 110 (18.2%) respondents were pregnant or had given birth. Some (n=19; 3.1%) used interruption of sexual intercourse as a method of contraception. From the list of contraception methods, the respondents most commonly used condoms (n=112; 18.5%) and contraceptive pills (n=80; 13.2%).

Based on the Pearson correlation coefficient, we detected strong linear associations between desire and arousal (r=0.856), arousal and lubrication (r=0.879), lubrication and arousal (r=0.879), orgasm and arousal (r=0.862), satisfaction and orgasm (r=0.782), and pain and lubrication (r=0.782) (Table 9).

Table 9. Pearson correlation coefficient among claims.

| Desire | Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasm | Satisfaction | Pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire | - | 0.585* | 0.470* | 0.434* | 0.455* | 0.348* |

| Arousal | 0.585* | - | 0.879* | 0.856* | 0.770* | 0.776* |

| Lubrication | 0.470* | 0.879* | - | 0.839* | 0.749* | 0.856* |

| Orgasm | 0.434* | 0.856* | 0.849* | - | 0.782* | 0.757* |

| Satisfaction | 0.455* | 0.779* | 0.749* | 0.782* | - | 0.717* |

| Pain | 0.348* | 0.765* | 0.856* | 0.757* | 0.717* | - |

*Correlation significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

The estimation of FSD was based on the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis (43). The prevalence was estimated based on the model that contains one variable, which represents the total score of points in all domains. If the total number of points is equal to or greater than 26.55, sexual dysfunction is not present in 88.1% of cases. However, if the result is lower, sexual dysfunction is present in at least one of the domains in 77.7% of cases. Accordingly, the risk of sexual dysfunction is present in each subject with a total score of 26.55 or lower.

To calculate the prevalence, we initially divided the sample into two groups: one group including women with a total score of FSFI higher than 26.55 and the other one with a lower score. In each group, we calculated the sum of all female subjects. In the first group, we recorded a higher overall result in 375 (69%) and in the second group in 169 (31%) subjects. The results obtained yielded the prevalence of FSD in Slovenia of 31%.

Discussion

Based on our research, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in Slovenia is 31%. Several exogenous and endogenous factors influence the subjective meaning of sexuality. Among endogenous factors, the organic substratum, i.e. pathology and pathophysiology of tissues, should be mentioned. The psychological factors also play a significant role in the individual perception of the appropriate or inappropriate sexual stimuli. Basson et al. (15) argued that depression interfered with female sexual response, with a negative association among desire, arousal, satisfaction, orgasm, and pain. Future studies should not just involve individual perceptions and (mis)understandings, but as Meils et al. (44) argued, the impact of the couple’s relationship quality in sexual function should be investigated.

With the growth and development of the female body, changes occur in the perception, understanding and needs of sexual stimuli. The youngest females (18-23 and 24-29 age groups) reported higher levels of the physiological and psychological stimuli linked with desire, arousal and satisfaction. At later ages (42-47 age group), changes also occur, focused on lubrication, orgasm, and pain. In addition to age, the level of education represents a strong influential factor. Sexual stimuli are oriented on arousal and orgasm.

In addition to growth, development, chronologic age and education, sexual stimuli are influenced by several other factors, such as acquisition of knowledge, adoption of values, and spiritual growth (45-47).

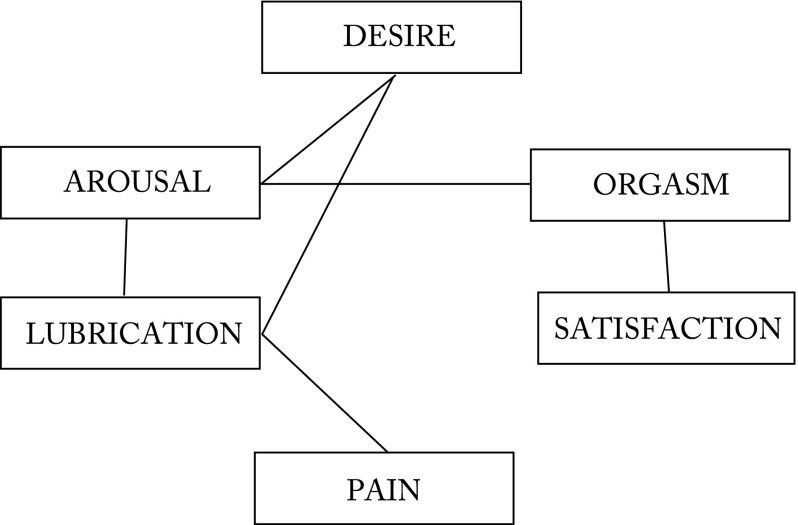

Based on our study, we conclude that arousal is linked to desire, orgasm, and lubrication. Lubrication affects desire and pain, and orgasm plays a vital role in satisfaction (Fig. 1). Theoretically, from the physiological/psychological point of view, we could conclude that the sexual cycle first involves desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and finally satisfaction. It is interesting that the claim of orgasm is not linked to desire and lubrication. Theoretically, orgasm cannot occur without arousal and lubrication, and previously without desire.

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of correlations.

More studies will be required to respond to the issue of whether orgasm can occur during the rape of female victims (48).

Limitations

The current research had some limitations. We should note that sexual dysfunction itself has a diverse etiology, and we could not be entirely objective. Other limitations arose from the methodology: 1) we did not use face-to-face interviews because they could embarrass people when talking about privacy issues, although, according to some authors, data compiled through methods such as online surveys are fraught with bias and misinformation; and 2) the unequal distribution of the questionnaires might affect the demographic correlations made in the study.

Conclusions

This study was one of the first attempts to assess the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among female adults in Slovenia. We took a well-validated, commonly used questionnaire for fast and accurate screening of FSD. The study significantly contributed to the understanding of female sexual function and the influence of age and level of education on the perception, understanding and needs of sexual stimuli, and on the prevalence of FSD in Slovenia.

References

- 1.de Jong PJ, Schultz WW, Peters KL, Buwalda FM. Disgust and contamination sensitivity in vaginismus and dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:244–52. 10.1007/s10508-007-9240-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Channon LD, Ballinger SE. Some aspects of sexuality and vaginal symptoms during menopause and their relation to anxiety and depression. Br J Med Psychol. 1986;59:173–80. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1986.tb02682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR. Sexuality in sexagenarian women. Maturitas. 1991;13:43–50. 10.1016/0378-5122(91)90284-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein MK, Teng NN. Gynecologic factors in sexual dysfunction of the older woman. Clin Geriatr Med. 1991;7:41–61. 10.1016/S0749-0690(18)30564-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virtanen H, Makinen J, Tenho T, Kiilholm P, Pitkanen Y, Hirvonen T. Effects of hysterectomy on urinary and sexual symptoms. Br J Urol. 1993;72:868–72. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1993.tb16288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thranov I, Klee M. Sexuality among gynecologic cancer patients – a cross-sectional study. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:14–9. 10.1006/gyno.1994.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis SR, Burger HG. Clinical review 82: androgens and the post-menopausal woman. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2759–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cawood EH, Bancroft J. Steroid hormones, the menopause, sexuality and well-being of women. Psychol Med. 1996;26:925–36. 10.1017/S0033291700035261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton AH, McGarvey EL, Clavet GJ. The Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ): development, reliability, and validity. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:731–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finger WW, Lund M, Slagle MA. Medications that may contribute to sexual disorders: a guide to assessment and treatment in family practice. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laan E, van Lunsen RH. Hormones and sexuality in postmenopausal women: a psychophysiological study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;18:126–33. 10.3109/01674829709085579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–14. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen R. Sexual dysfunction in the United States. JAMA. 1999;281:537–44. 10.1001/jama.281.6.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. 10.1080/009262300278597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, Derogatis L, Ferguson D, Fourcroy J, et al. Report of the International Consensus Development Conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163:888–93. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67828-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlow BL, Wise LA, Stewart EG. Prevalence and predictors of chronic lower genital tract discomfort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:545–50. 10.1067/mob.2001.116748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiss IM, Umek WH, Dungl A, Sam C, Eiss P, Hanzal E. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in gynecologic and urogynecologic patients according to the international consensus classification. Urology. 2003;62:514–8. 10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00487-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quirk FH, Heiman JR, Rosen RC, Laan E, Smith MD, Boolel M. Development of a sexual function questionnaire for clinical trials of female sexual dysfunction. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:277–89. 10.1089/152460902753668475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 2003;58:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Kohorn EI, Minkin MJ, Kerns RD. Assessing Sexual Function and Dyspareunia with the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with vulvodynia. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:315–24. 10.1080/00926230490463264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed BD, Crawford S, Couper M, Cave C, Haefner HK. Pain at the vulvar vestibule: a web-based survey. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2004;8(1):48–57. 10.1097/00128360-200401000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basson R. Women’s sexual dysfunction: revise and expanded definitions [review]. CMAJ. 2005;172:1327–33. 10.1503/cmaj.1020174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reissing ED, Yitzchak BM, Khalife SMD, Cohen DMD, Amsel RMA. Vaginal spasm, pain and behavior: an empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:5–17. 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000007458.32852.c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidi H, Abdullah N, Puteh SEW, Midin M. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): validation of the Malay version. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1642–54. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Dolezal C. The Female Sexual Function Index: a methodological critique and suggestions for improvement. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33:217–24. 10.1080/00926230701267852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerstenberger EP, Rosen RC, Brewer JV, Meston CM, Brotto LA, Wiegel M, et al. Sexual desire and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a sexual desire cutpoint for clinical interpretation of the FSFI in women with and without hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3096–103. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isidori AM, Pozza C, Esposito K, Giugliano Morano S, Vignozzi L, Corona G, et al. Development and validation of a 6-item version of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) as a diagnostic tool for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1139–46. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, Legocki LJ, Edwards M, Arato N, Haefner HC. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;206(2):170, e1-e9, doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Holla K, Jezek S, Weiss P, Pastor Z, Holly M. The prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction among Czech women. J Sex Health. 2012;24:218–25. 10.1080/19317611.2012.695326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legocki LJ, Aikens JE, Sen A, Haefner HK, Reed BD. Interpretation of the Sexual Functioning Questionnaire in the presence of vulvar pain. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(3):273–9. 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31826ca384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts SC, Cobey KD, Klapilová K, Havlíček J. An evolutionary approach offers a fresh perspective on the relationship between oral contraception and sexual desire. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:1369–75. 10.1007/s10508-013-0126-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts SC, Cobey KD, Klapilová K. Havlíček. Oral contraceptives and sexual desire: replies to Graham and Bancroft (2013) and Puts and Pope (2013) [Letter to the Editor]. Arch Sex Behav. 2014a;43:3–6. 10.1007/s10508-013-0236-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith WJ, Beadle K, Shuster EJ. The impact of a group psychoeducational appointment on women with sexual dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:697.e1–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang SCH, Klein C, Gorzalka BB. Perceived prevalence and definitions of sexual dysfunction as predictors of sexual function and satisfaction. J Sex Res. 2013;50(5):502–12. 10.1080/00224499.2012.661488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeRogatis LR, Allgood A, Rosen RC, Leiblum S, Zipfer L, Guo CY. Development and evaluation of the Women’s Sexual Interest Diagnostic Interview (WSID): a structured interview to diagnose hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in standardized patients. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2827–41. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burri AV, Cherkas LM, Spector TD. The genetics and epidemiology of female sexual dysfunction: a review. J Sex Med. 2009;6:646–57. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kedde H, Donker G, Leusink P, Kruijer H. The incidence of sexual dysfunction in patients attending Dutch general practitioners. Int J Sex Health. 2011;23:227–77. 10.1080/19317611.2011.620686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen RC, Taylor JF, Leiblum SR, Bachmann GA. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women. Results of a survey study of 329 women in an outpatient gynecological clinic. J Sex Marital Ther. 1993;19:171–88. 10.1080/00926239308404902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forbes MK, Baillie AJ, Schniering CA. Critical flaws in the Female Sexual Function Index and the International Index of Erectile Function. J Sex Res. 2014;51(5):485–91. 10.1080/00224499.2013.876607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Moreira ED, Jr, Paik A, Ginell C. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology. 2004;64(5):991–7. 10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simons JS, Carey MP. Sexual and gender identity disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2001; p. 493-538. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yule M, Davison J, Brotto L. The International Index of Erectile Function: a methodological critique and suggestions for improvement. J Sex Marital Ther. 2011;37:255–69. 10.1080/0092623X.2011.582431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31(1):1–20. 10.1080/00926230590475206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meils I, Litta P, Nappi L, Agus M, Benedetto Melis G, Angioni S. Sexual function in women with deep endometriosis: correlation with quality of life, intensity of pain, depression, anxiety, and body image. J Sex Health. 2015;27:175–85. 10.1080/19317611.2014.952394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Čukljek S, Jureša V, Grgas Bile C, Režek B. Changes in nursing students’ attitudes towards nursing during undergraduate study. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56:36–43. 10.20471/acc.2017.56.01.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mašina T, Madžar T, Musil V, Milošević M. Differences in health-promoting lifestyle profile among Croatian medical students to gender and year of study. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56:84–91. 10.20471/acc.2017.56.01.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zavoreo I, Gržinčić T, Preksavec M, Madžar T, Bašić Kes V. Sexual dysfunction and incidence of depression in multiple sclerosis patients. Acta Clin Croat. 2016;55:402–6. 10.20471/acc.2016.55.03.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levin RJ, van Berlo W. Sexual arousal and orgasm in subjects who experience forced or non-consensual sexual stimulation – a review. J Clin Forensic Med. 2004;11:82–8. 10.1016/j.jcfm.2003.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]