Abstract

Background:

The United States is facing an epidemic of opioid use and misuse leading to historically high rates of overdose. Community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution has effectively trained lay bystanders to recognize signs of overdose and administer naloxone for reversal. There has been a movement to encourage physicians to prescribe naloxone to all patients at risk of overdose; however, the rate of physician prescribing remains low. This study aims to describe resident knowledge of overdose risk assessment, naloxone prescribing practices, attitudes related to naloxone, and barriers to overdose prevention and naloxone prescription.

Methods:

The HOPE (Hospital-based Overdose Prevention and Education) Initiative is an educational campaign to teach internal medicine residents to assess overdose risk, provide risk reduction counseling, and prescribe naloxone. As part of a needs assessment, internal medicine residents at an academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland, were surveyed in 2015. Data were collected anonymously using Qualtrics.

Results:

Ninety-seven residents participated. Residents were overwhelmingly aware of naloxone (80%) and endorsed a willingness to prescribe (90%). Yet despite a high proportion of residents reporting patients in their panels at increased overdose risk (79%), few had prescribed naloxone (15%). Residents were willing to discuss overdose prevention strategies, although only a minority reported doing so (47%). The most common barriers to naloxone prescribing were related to knowledge gaps in how to prescribe and how to assess risk of overdose and identify candidates for naloxone (52% reporting low confidence in ability to identify patients who are at risk).

Conclusions:

Medicine residents are aware of naloxone and willing to prescribe it to at-risk patients. Due to decreased applied knowledge and limited self-efficacy, few residents have prescribed naloxone in the past. In order to improve rates of physician prescribing, initiatives must help physicians better assess risk of overdose and improve prescribing self-efficacy.

Keywords: Drug overdose, medical education, naloxone

Introduction

An epidemic of prescribed and illegal opioid use has led to substantial increases in morbidity and mortality.1 The growing number of prescription opioid users has increased the overall number of people at risk of overdose in the general population.1 Moreover, many persons with opioid use disorders begin with prescription opioids and eventually transition to heroin.2 Although overdose rates are highest among heroin users, more overdose deaths in the United States involve opioid analgesics than either heroin or cocaine combined due to the high rate of prescription opioid use.3

Opioid users describe high rates of both personal and witnessed overdoses,4,5 and the majority of overdose deaths occur in the company of others.6,7 Naloxone, an opioid antagonist, can rapidly reverse the effects of an overdose.8 Naloxone has been safely used for opioid reversal both in and out of the hospital with low rates of adverse effects.9 In the outpatient setting, naloxone has historically been administered by emergency first responders.10 There is often a 1-to 3-hour period from the onset of overdose-related symptoms to death,11 which provides first responders and bystanders the opportunity to recognize signs of overdose and intervene.10

Community opioid overdose prevention programs incorporate a variety of strategies, including naloxone prescription for opioid users and bystanders, to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with opioid overdose.12 Community distribution of naloxone has been associated with reductions in mortality from overdose.13 Although many community prevention programs successfully target those at the highest risk of unintentional overdose—injection drug users—they often do not reach prescription opioid users who are also at risk.14,15

There are high rates of illicit drug use in the United States, with nearly 1 in 10 Americans reporting use of an illicit drug in the past month.16 The clinical encounter is an opportunity for physicians to engage these patients in a conversation about opioid safety, to deliver overdose prevention education, and to write a naloxone prescription for at-risk individuals. Individuals with substance use disorders have frequent contact with primary care and acute care providers.17 Maryland data show that the majority of individuals who died from an overdose received medical care at least once in the year prior to their overdose.18 The clinical encounter is an opportunity to diagnose a substance use disorder and provide counseling to reduce harms associated with substance use. A national survey of primary care physicians and patients, however, found that physicians rarely identify substance use disorders in clinical settings.19 Many physicians fail to screen for or recognize signs of active substance use, let alone attempt to address overdose prevention.19,20 For many patients, these clinical encounters are missed opportunities to address addiction and mitigate risk.

Nearly 90% of patients with opioid prescriptions receive them from a single provider, which suggests that the primary care provider has a critical role in overdose prevention through both opioid stewardship and overdose education.21–25 Despite the support of various professional societies and local and national leadership,26–29 few physicians have incorporated overdose risk reduction into routine primary care practice.30 Physicians report limited knowledge about overdose prevention and limited exposure to naloxone prescription in the primary care setting.30,31 Discomfort with naloxone prescription may be representative of an overall discomfort in treating patients with substance use disorders.30 In prior surveys, physicians endorsed concerns about naloxone leading to riskier drug-using behaviors, worries about how and whom to educate, and uncertainty about how to identify those most at risk.30–32

Although there has been growing interest in teaching physicians mindful prescribing of opioids,33,34 there have been few interventions designed to teach primary care clinicians or physicians-in-training how to deliver opioid overdose education and prevention. Experiences during residency prove integral in shaping how physicians practice once they are on their own,19 including their comfort levels with a harm reduction paradigm.19,35 Few medical schools discuss overdose prevention and fewer residency programs incorporate it into their training.19,25,35 Incorporating overdose education and naloxone prescription into residency training is a potential method to facilitate physician prescribing in the community. To accomplish that goal, we created the Hospital-based Overdose Prevention and Education (HOPE) Initiative. The HOPE Initiative was created to teach internal medicine residents at an academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland, to assess overdose risk, provide risk reduction counseling, and prescribe naloxone. Our first objective was to evaluate resident knowledge of overdose risk assessment; our second objective was to document current naloxone prescribing practices; and our third objective was to evaluate attitudes related to administration of naloxone by lay bystanders and to elucidate barriers related to opioid overdose prevention and naloxone prescription.

Methods

Baseline education and naloxone access

Formal medical education for internal medicine residents at the target institution is typically provided in daily didactics, such as noon conference. For those house staff able to attend noon conference, approximately 3 noon conferences per year review aspects of substance use disorders (SUDs) and management of acute withdrawal during a hospitalization; however, there is no formal instruction and no policy related to overdose screening, overdose education, risk reduction counseling, or naloxone prescription delivered to internal medicine residents. Residents in our institution’s combined internal medicine and pediatrics (IM-P) program and the internal medicine primary care track receive additional training in SUDs through completion of a 1-month substance use rotation providing exposure to SUD diagnoses and treatment. During this experience, residents do not receive dedicated instruction on overdose prevention; however, they may receive additional informal exposures to naloxone prescription in the community. Despite limited formal medical education, residents may have had informal exposure to the idea of overdose prevention and naloxone use by lay bystanders in media coverage of health department initiatives, as there had been significant media attention to the overdose epidemic in Maryland in the year prior to our initiative and resident survey. The Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene released the Maryland Opioid Overdose Prevention Plan in 2013 and required individual health departments to submit local overdose prevention programs in the same year.36 Many of the plans discussed overdose prevention and incorporating broader naloxone distribution and training of lay bystanders into ongoing public health efforts. Despite these public health efforts, prior to the implementation of the HOPE Initiative, naloxone was not available to be filled for outpatient prescription at our hospital pharmacy, although residents who wished to do so were free to prescribe naloxone for patients to fill at other pharmacies. The HOPE Initiative was an educational campaign developed to fill an identified educational void. A needs assessment was conducted to facilitate design of targeted education and identify perceived barriers to risk reduction counseling and naloxone prescription prior to the launch of the HOPE Initiative.

Sample

As part of the needs assessment, all 132 internal medicine (IM) and 15 internal medicine-pediatric (IM-P) residents at an academic medical center in Baltimore, Maryland, were surveyed in February and March of 2015. The research was deemed exempt by the institutional review board. All survey responses collected from February 27, 2015, through March 4, 2015, were included in this analysis. Postgraduate year (PGY) training begins on July 1 of each academic year (e.g., PGY-1 residents had approximately 8 months of residency training at the time of completing the survey). IM-P residents alternate training in internal medicine and pediatrics approximately every 3 months, thus completing a minimum of 4 months of training in internal medicine.

Survey design

A survey instrument was designed to evaluate resident knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding opioid addiction, overdose education, and barriers to naloxone prescription. We queried both the academic literature and a national listserv of harm reduction programs and were unable to identify a validated survey instrument exploring detailed physician barriers to overdose prevention and naloxone prescription.30,31,37 There is a small, but rich qualitative body of literature exploring potential barriers to prescription that we used to guide our question development,38 as well as the limited body of literature looking at clinician attitudes related to naloxone.30,31,37 Although we established face validity with expert review and cognitive testing, we did not obtain additional measures, such as test-retest reliability because the purpose of the survey was predominantly descriptive. The instrument was shared with an expert in survey design with additional experience in naloxone distribution programs to get feedback on question structure and overall design of the instrument. We completed cognitive interviews with 3 physician participants. Participants were asked to discuss their thought process as they answered specific questions and were probed to determine why they answered questions in certain ways. Based on the results of the interviews, we revised wording and simplified several questions to remove ambiguity. We then piloted the electronic survey instrument with 6 physician participants to identify any issues with the electronic interface and difficulties understanding the questions or answer selections. There were a few technical issues with Qualtrics software that were identified and addressed at this stage, and 3 redundant questions were removed.

The survey instrument included questions on demographics, resident awareness of naloxone as an overdose reversal strategy, and resident exposure to patients with opioid use disorders or at risk of overdose with dichotomous responses (yes or no) (Supplemental material). Participants were asked to rank a series of statements about various beliefs and attitudes related to residency training, naloxone use, and overdose prevention using a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Those residents who denied prescribing naloxone in the past were presented with a list of potential barriers and were asked to rate them on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = not a concern to 4 = major concern. Residents were asked to evaluate statements about naloxone efficacy and legality. They were asked to respond do not know or were provided with a 4-point Likert scale that was coded from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The survey instrument included a total of 17 multipart questions and took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Survey implementation

The survey instrument was created using Qualtrics software.39 Residents were e-mailed links to the electronic survey. Residents received several electronic reminders during the study period about the survey instrument. Data were collected anonymously, and following completion of the electronic survey, participants were awarded a $10 electronic gift card for participation.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using Stata 13.0.40 Descriptive statistical analyses were completed looking at sample distribution, means, and standard deviations for participant characteristics, barriers, knowledge, and attitudes. We analyzed the Likert scale data individually and collapsed categories into dichotomized results (e.g., “strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” were analyzed individually and also collapsed into the category “agree”). Differences in proportions between levels of training were tested using chisquare test and Fisher’s exact test when cell size was small (N < 5). Because of the limited sample size and random distribution of missing data, all available data were included in the analysis of a given question. Missing data were excluded in pairwise fashion. Item-level missingness ranged from 0% to 9.3%.

Results

Respondent characteristics

In total, 132 internal medicine and 15 MP residents were emailed links to the survey; of these, 97 (66.0%) participated. Responses were fairly evenly split amongst first- (n = 32), second- (n = 29), and final- (n = 36) year residents, with slightly more responses amongst third and fourth years. Approximately 42.8% of the resident respondents were female. The majority of the resident respondents were white (n = 69; 61.9%), a minority were Asian (n = 25; 25.8%), followed by black or African American (n = 2; 2.1%), and American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 1; 1.0%). The demographics are representative of the overall resident population.

Substance use disorder (SUD) training in residency and baseline attitudes

Addiction training during residency was viewed as important, with 64% (n = 56) saying they “strongly agreed” and 30% (n = 26) of residents saying that they “somewhat agreed” that trainees should get education on addiction. In particular, 60% (n = 53) of residents “strongly agreed” and 35% (n = 31) “somewhat agreed” that it was important to learn how to counsel patients about drug overdose during residency. Despite their interest, only a small majority (53%) reported receiving sufficient training in addiction in residency (n = 49). In addition, only 52% of residents were confident in their ability to counsel patients about strategies to minimize overdose (n = 48). Residents reported several knowledge deficits, with only 43% (n = 40) reporting that they know how to educate patients on strategies to minimize overdose risk and only 16% (n = 15) reporting they know how to prescribe naloxone. Sixty-three percent agreed that they do not know the indications to prescribe naloxone for outpatient use (n = 57).

Residents reported feeling that it was their responsibility to counsel patients about overdose, with a majority of residents (88%; n = 83) disagreeing with the statement that it is not their responsibility to educate patients. Nearly 95% (n = 84) of residents agreed that it is important to learn to counsel patients about overdose during residency. Almost 82% (n = 78) of survey respondents were aware of naloxone use for patients in the community, and 84% (n= 75) were willing to prescribe naloxone to at-risk patients.

Experience with naloxone and overdose prevention

Residents reported high rates of routine exposure to patients who misuse opioids and those at risk of overdose (Table 1). A large majority of residents reported having patients in their outpatient clinical panels who either misuse prescription opioids (67%) or are at risk of an overdose (79%); however, nearly half of residents (49%) reported low confidence in their ability to accurately determine which patients are at risk of overdose. Although sample size limits power to find statistically significant differences between years, with each additional year of training a greater proportion of residents report having patients in their clinic panel who misuse prescription opioids. A greater proportion of residents in their final year reported discussing overdose risk and prevention strategies compared with first-year residents despite similar percentages who reported seeing patients at risk of overdose. Few residents reported prescribing naloxone to at-risk patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline experience with opioid addiction and naloxone amongst respondents, by level of postgraduate year (PGY) training.

| Experience | PGY-1 (N = 32) n (%) | PGY-2 (N = 29) n (%) | PGY-3 and -4 (N = 36) n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aware of naloxone as OD prevention Yes | 25 (80.7) | 25 (86.2) | 28 (77.8) | 78 (81.2) |

| Patients in clinic panel misusing prescription opioids Yes | 17 (56.7) | 19 (67.9) | 27 (75.0) | 63 (67.0) |

| Patients at risk of OD in clinic panel Yes | 25 (83.3) | 20 (71.4) | 29 (80.6) | 74 (78.7) |

| Ever discussed risk of OD and OD prevention with patients Yes | 9 (30.0) | 15 (53.6) | 20 (55.6) | 44 (46.8) |

| Ever prescribed naloxone to patients Yes | 7 (22.6) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (11.1) | 15 (15.6) |

Note. OD = overdose. Response categories were dichotomous: yes or no. Differences in proportions between levels of training were tested using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test when cell size was small (n < 5). P values for between year differences was >.05.

Despite willingness to both deliver overdose education and prescribe naloxone to their at-risk patients, slightly less than half of residents, 46.8%, reported having ever discussed overdose risk and prevention with their patients. Few residents (15%) had previously prescribed naloxone for use in a community setting.

Knowledge and beliefs regarding efficacy and legality of naloxone prescription

Residents’ knowledge and beliefs regarding naloxone efficacy and legality are presented in Table 2. Residents were confident that overdose education is effective in teaching patients to dial 911 in case of an overdose (52.8% somewhat or strongly agreeing in its efficacy) and that naloxone is an effective tool to reduce opioid-related deaths (86.5% somewhat or strongly agreeing). Residents did not believe that naloxone prescriptions were enabling (86.5% disagreed with this statement), or would promote increased (92.1% disagreed) or riskier (84.3% disagreed) use (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge and beliefs about practical implications of naloxone prescription: Legality and efficacy.

| Knowledge | Do not know n (%) | Strongly disagree n (%) | Somewhat disagree n (%) | Somewhat agree n (%) | Strongly agree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge regarding legality* | |||||

| My patient or bystander could get arrested for being at an OD.b | 25 (28.1) | 39 (43.8) | 17 (19.1) | 8 (9.0) | 0 |

| My patient or bystander could be arrested for giving naloxone to someone who is overdosing.b | 23 (25.8) | 52 (58.4) | 8 (9.0) | 6 (6.7) | 0 |

| Prescribing naloxone for my individual patients is legal.a | 15 (16.9) | 10 (11.2) | 8 (9.0) | 21 (23.6) | 35 (39.3) |

| Prescribing naloxone to my patients to use on others who are overdosing is illegal.c | 29 (32.6) | 25 (28.1) | 16 (18.0) | 13 (14.6) | 6 (6.7) |

| Knowledge and beliefs regarding efficacy | |||||

| OD education is effective in teaching people to dial 911 when someone overdoses.* | 21 (23.6) | 3 (3.4) | 18 (20.2) | 34 (38.2) | 13 (14.6) |

| OD education is effective at getting people to give rescue breaths during at OD.* | 26 (29.2) | 9 (10.1) | 22 (24.7) | 28 (31.5) | 4 (4.5) |

| Naloxone is an effective tool to reduce opioid-related OD deaths.† | — | 6 (6.7) | 6 (6.7) | 42 (47.2) | 35 (39.3) |

| Giving patients naloxone for OD reversal will cause them to use more drugs.† | — | 39 (43.8) | 43 (48.3) | 7 (7.9) | 0 |

| Giving patients naloxone for OD reversal will cause them to use drugs in riskier ways.† | — | 37 (41.6) | 38 (42.7) | 13 (14.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| Giving patients naloxone for OD reversal enables illegal drug use.† | — | 44 (49.4) | 33 (37.1) | 12 (13.5) | 0 |

Note. OD = overdose.

Score range: 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Somewhat disagree; 3 = Somewhat agree; 4 = Strongly agree.

Score range: 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Somewhat disagree; 3 = Somewhat agree; 4 = Strongly agree.

In Maryland, this statement is true.

In Maryland, this statement is false.

At the time of the survey, in Maryland, prescribers were only able to provide third-party prescriptions to parties who completed state-approved training programs and received a certificate. This has recently changed.

Regarding legal issues, 63% of respondents correctly recognized that prescribing naloxone for individual patients was legal; however, they were uncertain (28% reported not knowing) if individuals could be arrested for being at the scene of an overdose, and 26% reported not knowing if giving naloxone to an individual who is overdosing is legal; both of which are legal in Maryland (Table 2).

Barriers to naloxone prescription and overdose education

Among all participants, the majority of residents 57% (n = 54) endorsed limited knowledge on how to educate patients on strategies to minimize overdose risk, on the indications for prescribing naloxone (63%; n = 59), and on logistics of prescribing for outpatient use (84%; n = 79). The deficits in knowledge identified by residents appear to contribute to barriers to naloxone prescription in nonprescribers.

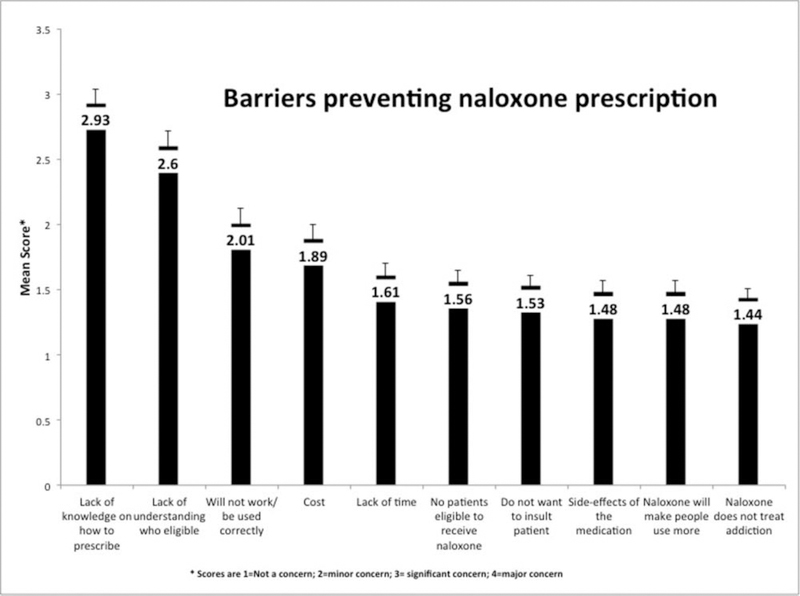

Focusing exclusively on those residents who had not prescribed naloxone (Figure 1), on a Likert scale from 1 = not a concern to 4 = major concern, the most commonly identified barriers were lack of knowledge on how to prescribe, with a mean (SD) of 2.93 (0.11) and inability to determine eligibility with a mean (SD) of 2.60 (0.12). Concerns about improper or ineffectual use or administration were a minor concern; mean (SD) = 2.01 (0.11).

Figure 1.

Barriers to naloxone prescription identified by internal medicine residents.

Discussion

Resident participants in our study endorsed overwhelmingly positive attitudes related to overdose prevention and naloxone prescription. Although prior studies have examined the attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge of practicing physicians, the perspectives of physicians-in-training has not previously been well characterized. Prior research has found low levels of awareness of naloxone as an overdose reversal strategy, even among practicing physicians with frequent exposure to at-risk patients.30

The first objective of the HOPE Initiative was to evaluate internal medicine resident knowledge of overdose prevention and awareness of naloxone as an overdose prevention strategy. In contrast to other reports in the literature (with less than a quarter of surveyed physicians aware of naloxone as overdose prevention strategy),30 the resident participants in the HOPE Initiative reported high levels of familiarity with naloxone. Furthermore, in contrast to a national sample of physicians that found low levels of willingness to prescribe naloxone amongst current practitioners (with 54% of physicians saying they would never consider prescribing naloxone to a patient who injects drugs),30 the vast majority of resident physicians in our study reported that they were willing to prescribe naloxone to their at-risk patients and, in fact, believed it to be their responsibility. The residents believed that it was important to receive education during residency about addiction and also in specific tasks, such as counseling patients to prevent overdose. Previous studies cite negative clinician beliefs related to naloxone (e.g., concerns about naloxone leading to increased or riskier opioid use) as potential drivers for limited uptake of naloxone.31 Encouragingly, the residents in our study correctly identified these concerns as erroneous.

The high proportion of residents in our study aware of naloxone may reflect the recent state and national push encouraging physicians to prescribe naloxone in all clinical settings.26–29 Additionally, Maryland has made a coordinated effort to address overdose at the state and local levels, which has led to increased publicity and targeted community-outreach.36,41 For example, researchers from the institution have been influential in partnering with the Baltimore City Health Department to design and evaluate Staying Alive, a program providing overdose education and naloxone to injection drug users as part of the citywide needle exchange program.42,43 Researchers from the schools of public health and medicine, as well as clinicians affiliated with the institution, have been at the forefront of efforts calling for a coordinated national strategy to address the opioid epidemic, including calling for more routine use of naloxone.44,45 The physicians-in-training at our institution may be more aware of naloxone use because of the environmental context, which suggests that state and local efforts have been effective in increasing awareness and willingness to prescribe naloxone. It is important to note that although these findings may have contributed to greater familiarity among residents with naloxone, it did not lead to greater experience prescribing it. Although Maryland’s context may be unique, the growing national attention on the overdose epidemic and on comprehensive strategies to reduce overdose suggests that we may soon see greater national recognition of naloxone amongst physicians. Our findings may represent a shift in generational awareness as “naloxone as prevention” moves from being regarded as a fringe public health idea to a clinical recommendation with a growing body of evidence; however, our data suggest that interventions targeted solely at increasing physician awareness may not necessarily lead to the desired change in prescribing behaviors.

In a seeming contradiction, the majority of residents in our study described having both patients at risk of overdose and also low confidence in their ability to identify those at risk. It may be that residents have an easier time identifying and discussing with patients some risk factors for increased overdose risk as opposed to others. There is also a lack of consensus in the literature on the patient factors that are necessarily associated with an increased risk of overdose. Resident confusion could be driven by some of this lack of specificity. It is also possible that residents may be underreporting their self-confidence or may have had difficulty understanding the wording of the question. We need further research to determine if residents’ self-evaluation of their assessment skills is valid, and to identify the factors that influence the process of risk assessment by a resident. We need to further evaluate if the deficits are based on residents’ lack of knowledge about risk factors or difficulty in discussing these risk factors with patients, or if the deficits are due to some combination of both. Nationally, physicians have been found to underdiagnose substance use disorders, and so it would not be surprising if residents underestimate both the prevalence of opioid use disorders and overdose risk in their patients.19

The second objective of the study was to document current rates of naloxone prescribing. Despite high rates of familiarity with naloxone for prevention of death from opioid overdose, similarly high endorsement of willingness to prescribe it, and a high number of residents who report eligible patients in their panels, the majority of residents in our study had never previously prescribed naloxone. The self-reported prescribing rates of naloxone were relatively high (15%) compared with previously published studies. Previous studies have revealed not only low prescribing rates of less than 5%,31 but also limited willingness to prescribe naloxone (with only a third of physicians in one cohort willing to prescribe)37 and low levels of familiarity with naloxone as an overdose prevention strategy.30–32 Residents in our study reported caring for a high-acuity patient population, with the majority reporting exposure to patients with opioid use. In this context, even a 15% rate represents low levels of prescribing behavior relative to unmet need.

There are several factors that may be driving the gap between residents’ awareness and endorsement of naloxone as an overdose prevention strategy and their actual prescribing behavior. Although the literature identifies limited knowledge of naloxone and low willingness as barriers to more mainstream use of naloxone prescription in clinical settings,30–32,37,38 these are not barriers for the resident physicians in our study. The gap may be explained by low self-efficacy around naloxone prescribing amongst residents. Resident self-efficacy, that is, confidence in their knowledge and abilities in this area, was low with respect to identifying at-risk patients, as well as navigating the logistics of prescribing naloxone to at-risk patients. Although residents were more likely to discuss overdose risk and prevention strategies with additional years of training, there was no similar relationship seen for naloxone prescribing. This suggests that residents may be receiving informal training during residency that encourages them to offer counseling, but that training about naloxone prescribing is not adequate, contributing to low self-efficacy. The results of our study suggest that in order to improve rates of physician prescribing, educational initiatives for residents should target interventions helping physicians assess overdose risk, provide appropriate and targeted education to patients, and better enable prescription of naloxone.

Although the study provides some important insights into how residents think about naloxone and overdose, there are several limitations. First, the single-institution nature of the study may limit its generalizability, especially in light of the scope of the opioid epidemic within the surrounding community and the hospital’s catchment area. Residents in our study report high levels of familiarity with naloxone as an overdose prevention strategy, which likely reflects their unique exposures to naloxone interventions at both a state and a local level. It is unclear whether the attitudes and beliefs of residents with lower levels of baseline exposure to the opioid epidemic or naloxone would be comparable. Furthermore, although the survey response rate was similar or higher than that reported in similar electronic survey studies, we have no data on the residents who opted not to participate or did not complete the survey. The nonresponders or noncompleters may be less aware of naloxone or may view naloxone less favorably than those who did participate, biasing our results. Another limitation of our study includes the heterogeneity of the resident population with respect to training. Approximately 10% of the total residents surveyed were IM-P residents. In order to preserve anonymity, we did not separate out IM-P and IM resident responses. Although IM-P residents had less exposure to SUDs while on pediatrics, they received additional exposure due to a mandatory SUD rotation, likely neutralizing the impact of decreased pediatric experiences. Additionally, our survey is not a formally validated instrument. Because the survey instrument was used for a descriptive study, we used cognitive testing, expert review, and survey piloting to address face and content validity of the instrument; however, we did not measure internal and external validity or evaluate test-retest reliability. This limits our ability to fully evaluate the accuracy of the survey instrument in measuring respondent behaviors and limits our ability to predict responses overtime. Finally, the cross-sectional study design precludes our ability to make causal inferences about what is driving naloxone prescribing intention or practice.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides novel data about the high rates of resident physician awareness of naloxone for use in the community, as well as willingness to prescribe naloxone to at-risk patients. Our data reveal that limited applied knowledge of and poor self-efficacy related to naloxone prescribing contribute to high rates of unmet need. The HOPE Initiative is an ongoing quality improvement initiative with interventions based on the results of the resident physician survey. As more residents incorporate naloxone prescription into their practice, they will serve as models for other trainees and create a culture where naloxone prescription and overdose education becomes regular and routine. Future research will evaluate whether the HOPE intervention bundle improves applied knowledge, self-efficacy, and prescription writing rates.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hoover Adger and Dr. Susan Sherman provided valuable support on construction of the survey instrument and research design. The Urban Health Internal Medicine-Pediatrics residents provided feedback essential in the design and creation of the HOPE Initiative. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Program. Dr. J. Deanna Wilson was supported through two training awards: the HRSA/MCH/T71MC08054 and T32HD052459-07. Dr. Pamela Matson was supported through NIH K01DA035387. It had no role in the design, conduct, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data. There was no communication about preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The funder solely received a summary of the proposed project at the project’s inception.

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control. Prescription drug overdose. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/. Accessed June 8, 2015.

- [2].Krisberg K Fatal heroin overdoses on increase as use skyrockets: health officials battling opiate epidemic. Nations Health. 2014;44 (4):1–10. http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/44/4/1.1. Accessed February 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Centers for Disease Control. Policy impact: prescription painkiller overdose. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/policyimpact-prescriptionpainkillerod-a.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed July 4, 2015.

- [4].Grau LE, Green TC, Torban M, et al. Psychosocial and contextual correlates of opioid overdose risk among drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. Harm Reduct J. 2009;4:6–17. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Milloy MJ, Fairbairn N, Hayashi K, et al. Overdose experiences among injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. Harm Reduct J. 2010;13:7–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sergeev B, Karpets A, Sarang A, Tikhonov M. Prevalence and circumstances of opiate overdose among injection drug users in the Russian Federation. J Urban Health. 2003;80:212–219. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Strang J1, Manning V, Mayet S, et al. Overdose training and take-home naloxone for opiate users: prospective cohort study of impact on knowledge and attitudes and subsequent management of overdoses. Addiction. 2008;103:1648–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sporer KA. Strategies for preventing heroin overdose. BMJ. 2003;326:442–444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7386.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yealy DM, Paris PM, Kaplan RM, et al. The safety of pre-hospital naloxone administration by paramedics. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:902–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim D, Irwin KS, Khoshnood K. Expanded access to naloxone: options for critical response to the epidemic of opioid overdose mortality. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:402–407. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Boyer EW. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:146–155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wheeler E, Davidson PJ, Jones TS, Irwin KS. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:101–105. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6106a1.htm?s_cidDmm6106a1_w. Accessed July 3, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Walley A, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tobin KE, Sherman SG, Beilenson P, Welsh C, Latkin CA. Evaluation of the Staying Alive programme: training injection drug users to properly administer naloxone and save lives. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hammett TM, Phan S, Gaggin J, et al. Pharmacies as providers of expanded health services for people who inject drugs: a review of laws, policies and barriers in six countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].National Institute on Drug Abuse. Nationwide trends. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends. Updated June 2015. Accessed October 25, 2015.

- [17].Swenson-Britt E, Carrougher G, Martin BW, Brackley M. Project HOPE: changing care delivery for the substance abuse patient. Clin Nurse Spec. 2000;14:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Hospital utilization of deaths in 2013. http://bha.dhmh.maryland.gov/OVERDOSE_PREVENTION/SitePages/Data%20and%20Reports.aspx. Published 2014. Accessed February 17, 2015.

- [19].Survey Research Laboratory at University of Illinois Chicago. Missed Opportunity: National Survey of Primary Care Physicians and Patients on Substance Abuse. http://www.casacolumbia.org/addiction-research/reports/national-survey-primary-care-physicians-patients-substance-abuse. Published 2000. Accessed February 18, 2015.

- [20].Holland C Barriers to identification of Problem Alcohol and Drug Use: Results of Statewide Focus Groups [master’s thesis]. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health; 2007. http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/8828/1/HollandC_etd2007.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bowman S, Eiserman J, Beletsky L, Stancliff S, Bruce RD. Reducing the health consequences of opioid addiction in primary care. Am J Med. 2013;126:565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:85–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300:2613–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].United States Department of Health and Human Services. Addressing Prescription Drug Abuse in the United States. Current Activities and Future Opportunities. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/hhs_prescription_drug_abuse_report_09.2013.pdf. Published September 2013. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- [26].American Medical Association. AMA adopts new policies at annual meeting. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/news/news/2012-06-19-amaadopts-new-policies.page. Published 2012. Accessed February 17, 2015.

- [27].American Public Health Association. Reducing opioid overdose through education and naloxone distribution. http://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/16/13/08/reducing-opioid-overdose-through-education-and-naloxone-distribution. Published 2013. Accessed February 17, 2015.

- [28].American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public Policy Statement on the Use of Naloxone for the Prevention of Drug Overdose Deaths. http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/publicy-policy-statements/1naloxone-rev-8-14.pdf?sfvrsnD0. Published 2014. Accessed February 17, 2015.

- [29].Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. “Dear Treatment Provider.” http://bha.dhmh.maryland.gov/OVERDOSE_PREVENTION/Documents/October2014%20Naloxone%20Expansion%20Letter_Treatment%20Provider.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed February 17, 2015.

- [30].Beletsky L, Ruthazer R, Macalino GE, Rich JD, Tan L, Burris S. Physicians’ knowledge of and willingness to prescribe naloxone to reverse accidental opiate overdose: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2007;84:126–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Matheson C, Pflanz-Sinclair C, Aucott L, et al. Reducing drug related deaths: a pre-implementation assessment of knowledge, barriers and enablers for naloxone distribution through general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Green TC, Bowman SE, Zaller ND, Ray M, Case P, Heimer R. Barriers to medical support for prescription naloxone as overdose antidote for lay responders. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48:558–567. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.787099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kirschner N, Ginsburg J, Sulmasy LS, Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Prescription drug abuse: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:198–200. doi: 10.7326/M13-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim D, Irwin KS, Khoshnood K. Expanded access to naloxone: options for critical response to the epidemic of opioid overdose mortality. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:402–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Isaacson JH, Fleming M, Kraus M, Kahn R, Mundt M. A National survey of training in substance use disorders in residency programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:912–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland Opioid Overdose Prevention Plan. http://bha.dhmh.maryland.gov/OVERDOSE_PREVENTION/Documents/MarylandOpioidOverdosePreventionPlan2013%20(4).pdf. Published January 2013. Accessed October 25, 2015.

- [37].Coffin PO, Fuller C, Vadnai L, Blaney S, Galea S, Vlahov D. Preliminary evidence of health care providers support for naloxone prescription as overdose fatality prevention strategy in New York City. J Urban Health. 2003;80:288–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Van Wert MJ, Gatewood A, Andrada A. Perceived barriers to prescribing naloxone to third parties as an overdose prevention strategy: a qualitative study of academic physician and medical student attitudes. Poster presented at 10th National Harm Reduction Conference; October 23–26, 2014; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Qualtrics. Qualtrics. Version 62232. Provo, UT: Qualtrics; 2015. www.Qualtrics.com. [Google Scholar]

- [40].StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dresser M Hogan unveils plan to fight heroin. Baltimore Sun. February 24, 2015 http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/politics/bs-md-hogan-heroin-20150224-story.html. Accessed October 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tobin KE, Sherman SG, Beilenson P, Welsh C, Latkin CA. Evaluation of the Staying Alive programme: training injection drug users to properly administer naloxone and save lives. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sherman SG, Gann DS, Tobin KE, Latkin CA, Welsh C, Bielenson P. “The life they save may be mine”: diffusion of overdose prevention information from a city sponsored programme. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Schwartz RP, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, et al. Opioid agonist treatments and heroin overdose deaths in Baltimore, Maryland, 1995–2009. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:917–922. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Alexander GC, Frattaroli S, Gielen AC, eds. The Prescription Opioid Epidemic: An Evidence-Based Approach. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2015. http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-drug-safety-and-effectiveness/opioid-epidemic-town-hall-2015/2015-prescription-opioid-epidemic-report.pdf. Published November 2015 Accessed December 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]