Antidepressants alter the function of their target membrane proteins. They also alter lipid bilayer properties and thereby affect other membrane proteins. Kapoor et al. use gramicidin A channels to probe how antidepressants affect the lipid bilayer, providing a new mechanism for their off-target effects.

Abstract

The two major classes of antidepressants, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), inhibit neurotransmitter reuptake at synapses. They also have off-target effects on proteins other than neurotransmitter transporters, which may contribute to both desired changes in brain function and the development of side effects. Many proteins modulated by antidepressants are bilayer spanning and coupled to the bilayer through hydrophobic interactions such that the conformational changes underlying their function will perturb the surrounding lipid bilayer, with an energetic cost (ΔGdef) that varies with changes in bilayer properties. Here, we test whether changes in ΔGdef caused by amphiphilic antidepressants partitioning into the bilayer are sufficient to alter membrane protein function. Using gramicidin A (gA) channels to probe whether TCAs and SSRIs alter the bilayer contribution to the free energy difference for the gramicidin monomer⇔dimer equilibrium (representing a well-defined conformational transition), we find that antidepressants alter gA channel activity with varying potency and no stereospecificity but with different effects on bilayer elasticity and intrinsic curvature. Measuring the antidepressant partition coefficients using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or cLogP shows that the bilayer-modifying potency is predicted quite well by the ITC-determined partition coefficients, and channel activity is doubled at an antidepressant/lipid mole ratio of 0.02–0.07. These results suggest a mechanism by which antidepressants could alter the function of diverse membrane proteins by partitioning into cell membranes and thereby altering the bilayer contribution to the energetics of membrane protein conformational changes.

Introduction

The initial discovery of antidepressive effects of three-ring structures that inhibited monoamine transporters (tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs]; Kuhn, 1958; Barsa and Sauders, 1961) catalyzed the search for drugs that selectively inhibit one monoamine transporter over another and led to the development of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (Hillhouse and Porter, 2015). TCAs and SSRIs in particular have been the mainstays of pharmacological intervention for depression- and anxiety-related disorders.

The specific monoamine transporter inhibitors inhibit neurotransmitter uptake with Kis in the nanomolar range (DeVane, 1999; Wang et al., 2013), with additional direct and/or downstream effects (Roth et al., 2004; Belmaker and Agam, 2008; Rantamäki and Yalcin, 2016). It remains unclear, however, how TCAs and SSRIs, or any treatment for depression, achieve their clinical results, reflecting the complex neural circuitry that underlies the disease pathology. Notably, TCAs and SSRIs have low-affinity interactions with a diverse group of membrane proteins (Rammes and Rupprecht, 2007; Bianchi, 2008; see also Table S1), which may provide additional mechanisms for altering neural chemistry and circuitry (Duman et al., 2016). The mechanisms underlying this polypharmacology remain unclear, but integral membrane proteins have two things in common: they are membrane spanning, and their activity can be modulated by changes in lipid bilayer properties (curvature, thickness, and elasticity) that can be induced by the addition of amphiphiles, including many biologically active molecules (e.g., a variety of toxins; Suchyna et al., 2004; Dockendorff et al., 2018), currently used or discontinued drugs (Rusinova et al., 2011, 2015), and phytochemicals (Ingólfsson et al., 2014; see also Lundbæk et al., 2010b, Table 3).

This bilayer-dependent regulation of membrane protein function by amphiphiles arises because (1) the conformational changes that underlie membrane protein function involve their bilayer-spanning domains and (2) membrane-embedded proteins locally organize their surrounding bilayer (Lundbæk et al., 2010b; see also Fig. 1).

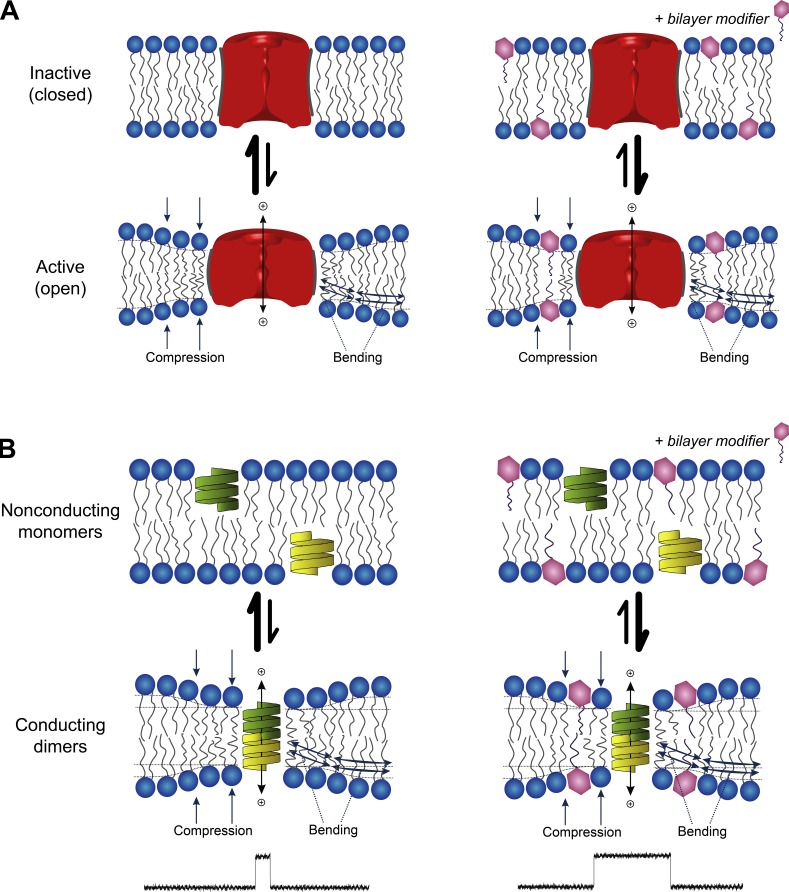

Figure 1.

Membrane proteins are energetically coupled to the lipid bilayer. (A) Schematic depiction of an ion channel that can exist in an inactive (closed) state and an active (open) state. The hydrophobic length of the two conformers differ, with the open state having the shorter hydrophobic length, leading to a hydrophobic mismatch between the protein’s hydrophobic domain and the bilayer hydrophobic core. In response, the bilayer adjusts by compressing and bending the surrounding lipids, which incurs an energetic cost. This bilayer deformation energy, as well as any residual mismatch energy (Mondal et al., 2011), will contribute to the equilibrium between the two conformational states and varies with changes in bilayer material properties, which can be altered by adsorption of small amphiphilic molecules. (B) Schematic depiction of gA channel formation. gA is a pentadecapeptide with β6.3-helical structure that dimerizes to form a transmembrane channel. The association/dissociation of the channel can be observed as changes in the single-channel current. The length of the conducting channel is less than the thickness of the bilayer, causing gramicidin channel activity (lifetime and frequency of appearance) to be dependent on the bilayer deformation energy. Changes in bilayer properties are observed as changes in lifetime and frequency.

This bilayer deformation has an energetic cost (ΔGdef) that depends on the protein–bilayer interface and varies with changes in bilayer material properties, such that the energetics of membrane protein conformational changes (e.g., a closed↔open [C↔O] transition in an ion channel; Fig. 1 A) will include a contribution from the bilayer: The total free energy change associated with the C↔O transition thus will be the sum of contributions intrinsic to the protein, and contributions from the bilayer, :

| (1) |

To determine whether antidepressants (ADs) in fact alter lipid bilayer properties, as sensed by bilayer-spanning channels, we used gramicidin A (gA) channels as probes to assess for drug-induced changes in bilayer properties (Ingolfson et al., 2008; Kapoor et al., 2008; Lundbæk et al., 2010a,b; Rusinova et al., 2011). gA forms conducting channels (Fig. 1 B) when two nonconducting monomers dimerize to form the transmembrane dimer (2 M ↔ D).The length (l) of the dimer (channel) is less than the thickness of the unperturbed bilayer (d0), resulting in hydrophobic mismatch, meaning that channel formation causes a local bilayer deformation with an associated ΔGdef (e.g., Huang, 1986; Nielsen and Andersen, 2000; Lundbæk et al., 2010b). The bilayer responds by imposing a disjoining force (Fdis) on the dimer, such that changes in ΔGdef (in ) are reflected as changes in the kinetics of channel formation (and are observed as altered single-channel lifetimes and appearance rates [the single-channel lifetime and channel appearance rate decrease as the disjoining force increases]). This renders gA channels sensitive to their host membrane environment and useful as probes of changes in bilayer properties (Lundbæk et al., 2010b); decreases in bilayer thickness, increases in bilayer elasticity, and/or a more positive intrinsic curvature will decrease ΔGdef and increase gA channel appearance frequencies (f) and lifetimes (τ).

Despite compelling evidence that ADs interact with membranes (e.g., Fisar, 2005), little is known about their bilayer-modifying effects other than that they tend to increase bilayer fluidity, and changes in fluidity are unlikely to be primary determinants of changes in membrane protein function (Lee, 1991), as they do not cause changes in the equilibrium distribution between conformational states. We therefore examined a library of 21 TCAs and SSRIs (see Table S2 for the structures, pKas, and calculated LogPs [cLogPs]) for their bilayer-modifying effects using the gA channels as probes, which allows us to quantify how the ADs alter the bilayer contribution to the gA monomer↔dimer equilibrium () as a global measure of the changes in bilayer properties. All 21 compounds shifted the gA monomer–dimer equilibrium toward the conducting dimers. Among the ADs examined, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline were the most bilayer-modifying compounds and zimelidine, citalopram, and alaproclate the least.

The rank order of bilayer-modifying potency was not satisfactorily predicted by the compounds’ hydrophobicity, as estimated using the cLogP or calculated LogD at pH 7.0 (cLogD7). The order was predicted quite well by the compounds’ bilayer/electrolyte partition coefficients measured using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Using single-channel electrophysiology, we find that the TCAs amitriptyline and imipramine and the SSRI citalopram altered primarily intrinsic curvature, and the SSRI fluoxetine altered primarily bilayer elasticity. Our results provide a novel mechanism for the ADs’ off-target effects and further show that a compound’s bilayer-modifying potency depends on its mole fraction in the membrane as well as its molecular structure.

Materials and methods

Materials

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), and 1,2-dierucoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DC22:1PC) were from Avanti Polar Lipids. n-decane (99.9% pure) was from ChemSampCo.

For the fluorescence experiments, we used a mixture of gramicidins A, B, and C isoforms purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. For the single-channel experiments, we used the 15-amino-acid analogue [Ala1]gA (AgA(15)) and the chain-shortened enantiomer des-(D-Val-Gly)gA− (gA−(13)), which were synthesized and purified as described previously (Greathouse et al., 1999).

The fluorophore 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (ANTS) disodium salt was from Invitrogen. Extravesicular ANTS was removed using PD-10 desalting columns from GE Healthcare.

Citalopram (+/−), citalopram (S+), and citalopram (R−) were gifts from H. Lundbeck A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark). All other drugs were from Sigma Chemical Co. and were of the highest available purity. All stocks were prepared in DMSO (Burdick and Jackson).

Methods

Gramicidin-based fluorescence assay

The gramicidin-based fluorescence assay has been described previously (Ingólfsson et al., 2010; Ingólfsson and Andersen, 2010). In brief, large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs), loaded with intravesicular ANTS (diameter, 150 ± 50 nm; Ingólfsson and Andersen, 2010) were prepared from DC22:1PC and gramicidin (gD) using freeze-drying, extrusion, and size-exclusion chromatography; the final lipid concentration was 4–5 mM, and the suspension was stored in the dark at 12.5°C for a maximum of 7 d. Before use, the LUV-ANTS stock was diluted to 200–250 µM lipid with NaNO3 buffer (140 mM NaNO3 and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7) and incubated with 260 nM gD for 24 h to allow the gramicidin monomers to cross the vesicle membrane.

The AD (dissolved in DMSO) or DMSO (as control) was added to a LUV-ANTS sample and equilibrated at 25°C in the dark for 10 min before the mixture was loaded onto a stopped-flow spectrofluorometer (SX.20; Applied Photophysics) and mixed with either NaNO3 buffer or TlNO3 buffer (Tl+ [thallous ion] is a gramicidin channel-permeant quencher of ANTS fluorescence). Samples were excited at 352 nm, and the fluorescence signal above 455 nm was recorded in the absence (four successive trials) or presence (nine successive trials) of the quencher. All ADs fluoresce to varying degrees, and the addition of these drugs to LUVs in control experiments without gA or Tl+ increased the fluorescence signal. The instrument has a dead time of <2 ms, and the next 2- to 100-ms segment of each fluorescence quench trace was fitted to a stretched exponential, which is a computationally efficient way to represent a sum of exponentials with a distribution of time constants, reflecting the distribution of LUV radii and number of gD channels in their membranes (e.g., Berberan-Santos et al., 2005):

| (2) |

where F(t) denotes the fluorescence intensity as a function of time, t; τ is a parameter with units of time; and β (0 < β ≤ 1, where β = 1 denotes a homogenous sample) is a measure of the LUV dispersity. The rate of Tl+ influx was determined at 2 ms (Berberan-Santos et al., 2005):

| (3) |

The quench rate for each experiment represents the average influx rate of the trials with Tl+. The quench rate was normalized to the rate in control experiment without drug, and the reported values represent averages from three or more experiments.

ITC

The binding of ADs to lipid vesicles was determined by measuring the heats of partitioning using an Auto-iTC200 isothermal titration calorimeter (Microcal) with 200 µl sample cell volume and 40 µl syringe volume. DC22:1PC LUVs without ANTS or gA were rehydrated in the same NaNO3 buffer as in the fluorescence assay. ADs were diluted from DMSO stock with NaNO3 buffer. The DMSO concentration was kept ≤1% and was matched between the lipid and drug samples to minimize any effects of the heats of dilution.

ADs were added to the sample cell and titrated with the DC22:1PC LUV suspension. The drug and lipid concentrations for each drug–lipid titration were optimized to give a large signal with a wide dynamic range that eventually saturated; control injections of LUVs into a drug-free cell produced minimal heat signals. An initial injection of 0.2 µl was discarded during the analysis to allow for cell–syringe equilibration artifacts. Then, 19 2-µl injections of the lipid suspension were spaced sufficiently apart (≥150 s) to ensure that the signal returned to baseline between injections. The enthalpy change generated by injection i () was determined by integrating the area under the curve of that injection using Origin 7 (OriginLab), as adapted by Microcal, for ITC data analysis.

Solute binding to lipid bilayers can be described as partitioning between two immiscible phases, which can be analyzed using different frameworks (Peitzsch and McLaughlin, 1993; Heerklotz and Blume, 2012; see also online supplemental material). Because ADs are amines (except for alaproclate, lofepramine, and zimelidine) that have pKas >9, they will be positively charged at pH 7. AD binding thus will confer a positive surface charge when they partition into the lipid–electrolyte interface, and their binding to lipid bilayers is conveniently analyzed as adsorption to the bilayer–electrolyte interface (e.g., Ketterer et al., 1971), where the surface solute density in the lipid phase (, in moles/area) is related to the aqueous solute concentration by an adsorption coefficient with units of length (K2):

| (4) |

AD adsorption into the bilayer–electrolyte interface will give rise to a surface charge, which in turn will establish a surface potential (), and the aqueous AD concentration at the interface ([AD]0) will differ from the bulk [AD]W (McLaughlin and Harary, 1976):

| (5) |

where zAD denotes the AD valence, F is Faraday’s constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in degrees kelvin. The effective adsorption coefficient () thus becomes

| (6) |

where

Each injection of an aliquot (volume δV) of a suspension of lipid vesicles (lipid concentration CL) into the system causes a redistribution of AD from the aqueous to the lipid phase with an ensuing heat production, After i injections, the cumulative heat production () becomes Eq. S23 in Supplemental Material):

| (7) |

where denotes the molar enthalpy of partitioning, and are the total amount of AD in the lipid phase after the ith injection and in the system, respectively, is the surface potential, VW is the initial volume of electrolyte in the calorimeter cell, and aL is the lipid molar area. can be estimated using the Gouy–Chapman theory of the diffuse double layer (Aveyard and Haydon, 1973). For univalent electrolytes (Eq. S28):

| (8) |

where ε is the dielectric constant, ε0 is the permittivity of free space, aD is the AD molar area, and CS is the total concentration of univalent salt (the factor 1,000 converts to concentrations in moles/liter to moles/m3). could then be estimated by fitting Eqs. 7 and 8 to the experimental relations (see online supplemental material for details) using the nonlinear least-squares fitting algorithm implemented in Matlab (The MathWorks Inc.).

Single-channel experiments

The single-channel bilayer punch method has been described previously (Ingolfson et al., 2008; Kapoor et al., 2008). In brief, a bilayer composed of DC18:1PC suspended in n-decane was formed across a 1- to 1.5-mm hole in a Teflon partition and doped with gA. (The total AgA(15) concentration in the system was a few pM in the DOPC experiments; the concentration of gA–(13) was ∼10-fold higher.) Punch electrodes, bent 90°, with a 20- to 40-µm opening were used to isolate small membrane patches and record electrical activity.

All experiments were done in 1 M NaCl (plus 10 mM HEPES, pH 7) at 25 ± 1°C at an applied potential of ±200 mV. The current signal was recorded and amplified using a Dagan 3900A patch clamp, filtered at 5 kHz, digitized and sampled at 20 KHz by a PC/AT compatible computer, and filtered at 200–500 Hz. Single-channel events were detected using a transition-based algorithm, and single-channel lifetimes were determined as described previously (Ingolfson et al., 2008; Kapoor et al., 2008). The average lifetimes were determined by fitting the results with single exponential distributions:

| (9) |

where τ denotes the average channel lifetime and N(t) the number of channels with durations longer than t. Eq. 9 was fit to the lifetime distributions using the nonlinear least-squares fitting routine in Origin 6.1 or 8.1 (OriginLab).

Online supplemental material

Table S1 summarizes TCAs' and SSRIs' effects on a number of membrane proteins. Table S2 summarizes physicochemical information about the TCAs and SSRIs tested in this study. Then follows a derivation of the analysis used in the ITC experiments. Fig. S1 shows the analysis of the ITC experiments with sertraline (an antidepressant with high partition coefficients) and paroxetine (an antidepressant with low partition coefficients); Fig. S2 summarizes the antidepressants' effects on the conductance of AgA(15) and gA−(13) channels; Fig. S3 shows the residuals from the straightline fit to the results in Fig. 8 A.

Results

Fluorescence quenching experiments

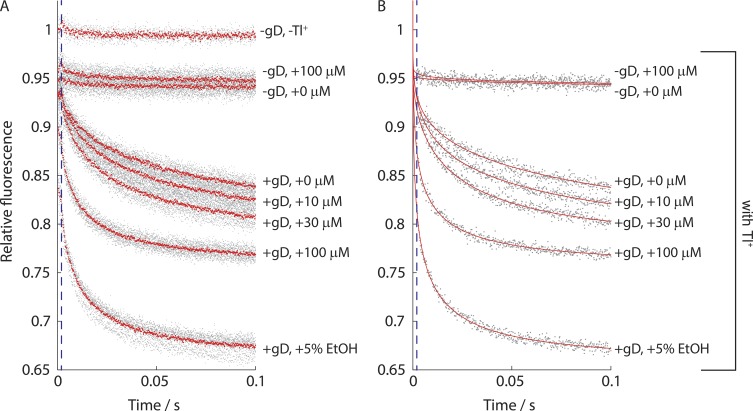

We tested the 21 compounds (Table S2) using the gA-based fluorescence assay. Fig. 2 shows results from an experiment with gA and increasing concentrations of racemic fluoxetine (R−/S+).

Figure 2.

Effect of fluoxetine (R−/S+) on the time course of ANTS fluorescence quenching. The gray dots represent individual experiments, with the data normalized to the maximum fluorescence in the absence of the quencher. (A) The red dots denote the average of the repeats for a given experimental condition. (B) The red line denotes a stretched exponential fit to each experiment. The blue stippled line demarcates 2 ms, where fluorescence quench rate was determined.

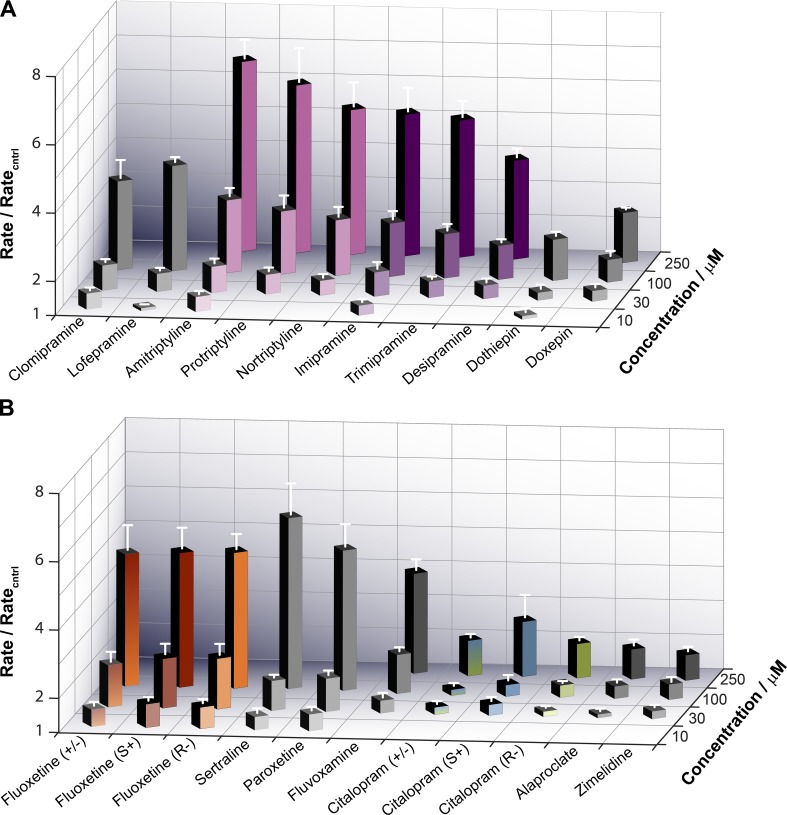

The quench rates were quantified at 2 ms, and the results from measurements with ADs were normalized to the control experiment (no drug, only DMSO) nearest in time. Fig. 3 summarizes results for 10 TCAs (Fig. 3 A) and 11 SSRIs (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

Summary of the antidepressants' effects on ANTS fluorescence quench rates. (A) Results for the TCAs. (B) Results for the SSRIs. Quench rates were quantified at 2 ms and the rates in the presence of the ADs were normalized to the control rate (no drug, only DMSO) determined in experiments nearest in time to the experiment with the AD. Only a subset of drugs, depending on their potency, were tested at the lowest (10 µM) and the highest (250 µM) concentrations.

All the tested ADs increased the fluorescence quench rate, indicating they increased the number of conducting gA channels in the LUV membrane. (As we show later, in Figs. 6 and S2, the ADs slightly decreased the single-channel conductance, so the increases in quench rate reflect increased numbers of channels.) Collectively, the ADs had widely varying potencies, but structurally similar compounds (amitriptyline-protriptyline-nortriptyline and imipramine-trimipramine-desipramine) tended to cluster together. There was no stereospecificity; the R enantiomers of fluoxetine and citalopram had the same effect on the fluorescence quench rate as their S counterparts.

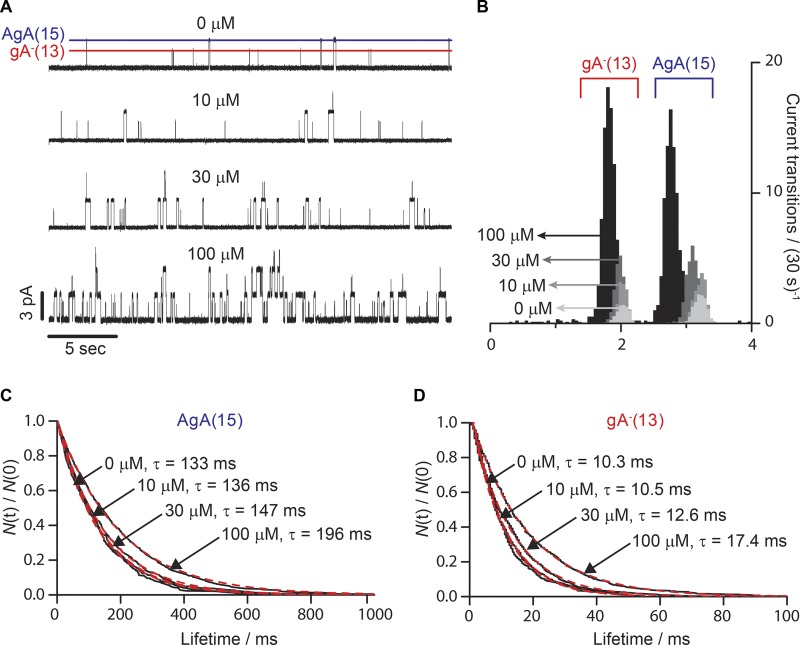

Figure 6.

Effect of amitriptyline on gA activity in the single-channel assay. (A) Single-channel current traces recorded with increasing concentrations of amitriptyline added to both sides of a DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayer doped with gA−(13) and AgA(15). The lines denote the current transition amplitudes for gA−(13) (red) and AgA(15) (blue). (B) Current transition amplitude histograms of gA−(13) and AgA(15). The darker the shading, the greater the amitriptyline concentration. In the absence of the drug, the characteristic current transition peaks were 3.2 ± 0.1 pA and 2.0 ± 0.1 pA for AgA(15) and gA−(13), respectively. 100 µM amitriptyline shifted the two peaks to 2.8 ± 0.1 and 1.8 ± 0.1 pA. (C and D) Normalized single-channel survivor histograms (black, solid lines) of AgA(15) (C) and gA−(13) (D). The histograms were fit with single exponential distributions (Eq. 7; red dotted lines), with lifetimes (τ).

ADs’ bilayer-modifying potencies were quantified by the concentration at which the quench rate was doubled, DAD, which was determined by fitting the straight line

| (10) |

to the results for each compound (Ingólfsson and Andersen, 2010). The results are summarized, and the ADs ranked from the most potent (Fluoxetine) to the least potent (Zimelidine), as estimated from the concentrations needed to double the quench rates (DAD), in Table 1. The SSRIs are on gray background; the TCAs are on white background.

Table 1. AD bilayer-modifying potency.

| Antidepressant | DAD /µM |

|---|---|

| Fluoxetine (S+/R−) | 16 |

| Fluoxetine (S+) | 17 |

| Fluoxetine (R−) | 18 |

| Paroxetine | 30 |

| Sertraline | 32 |

| Clomipramine | 39 |

| Lofepramine | 42 |

| Protriptyline | 52 |

| Amitriptyline | 53 |

| Nortriptyline | 61 |

| Trimipramine | 72 |

| Imipramine | 82 |

| Dothiepin | 83 |

| Fluvoxamine | 84 |

| Desipramine | 97 |

| Doxepin | 160 |

| Alaproclate | 220 |

| Citalopram (S+/R−) | 240 |

| Citalopram (R−) | 240 |

| Citalopram (S+) | 250 |

| Zimelidine | 290 |

The most potent modifiers of gA activity (DAD < 50 µM) were the SSRIs sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine and the two chlorinated TCAs (lofepramine and clomipramine). The least potent modifiers of gA activity (DAD >100 µM) were the SSRIs doxepin, citalopram, alaproclate, and zimelidine. The remaining drugs (the amitriptyline family, the imipramine family, dothiepin, and fluvoxamine) had intermediate potencies.

Though the TCAs tended to be distributed toward the middle and the SSRIs toward the extreme ends of the spectrum of bilayer-modifying potencies, both TCAs and SSRIs had representatives that cover the range of potencies. There was no correlation between drug class and tendency to alter bilayer properties.

Partitioning into the membrane (ITC)

To explore to what extent differences in the drugs’ bilayer-modifying potency reflect their partitioning into bilayers, we estimated their partition coefficients from their predicted octanol/water partition coefficients (cLogP; cf. Seydel, 2002; Mannhold et al., 2009) using the ACD/Percepta consensus algorithm (ACD/Percepta PhysChem Suite, 2012) and measured the adsorption coefficients () for a subset of the drugs using ITC (Seelig et al., 1993; Wenk and Seelig, 1997; Heerklotz and Seelig, 2000; Tan et al., 2002; Moreno et al., 2010). The drug concentrations in the calorimeter cell were matched to the highest tested concentration in the fluorescence assay (100 or 250 µM). The lipid concentration in the injectate varied between 15 and 50 mM.

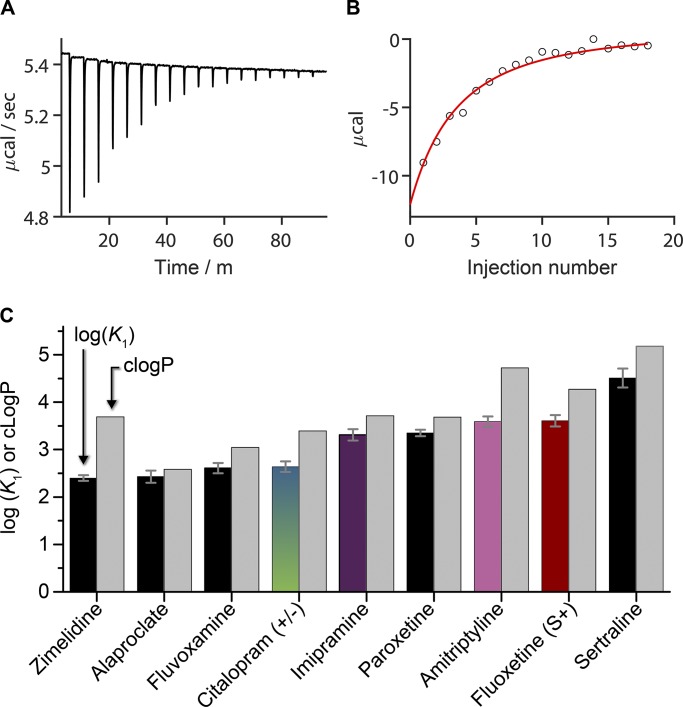

Fig. 4 A shows heats of reaction (partitioning) recorded when a 100-µM fluoxetine (S+) solution was titrated with 2-µl injections of a DC22:1PC LUV suspension (15 mM lipid). Fig. S1 shows results for paroxetine and sertraline, including the estimated changes in surface potential.

Figure 4.

Partition coefficients and molar enthalpies of partitioning determined by ITC as compared with cLogP. (A) Heats of reaction observed when 100 µM fluoxetine (S+) was titrated with 2-µl injections of 15 mM DC22:1PC LUVs (final lipid concentration in the cell was 2.4 mM). (B) The heats of binding from A were integrated to determine the cumulative reaction enthalpy (circles) for each injection. The results were fit by Eqs. 7 and 8 (solid line) to determine K2 (= 6.5 ⋅ 10−4 cm) and (= –2.5 kcal/mole), R2 = 0.97. (C) determined by ITC (left black or colored columns; colored columns denote compounds that were studied also using the electrophysiology assay) and estimated by cLogP (right gray columns; the consensus cLogP from the ACD/Percepta PhysChem Suite (2012). Values represent mean ± SE; n ≥ 3.

As fluoxetine (S+) partitioned into the LUVs at each injection, less of it became available for partitioning in subsequent additions, and the heat of reaction decreased with each injection. The cumulative reaction enthalpy (Fig. 4 B) was obtained by integrating the heats of partitioning for each injection, and the data were fit with a binding isotherm (Eqs. 7 and 8) to determine = 6.5 ⋅ 10−4 cm (R2 = 0.97). The average value (n = 6) was 9.2 ⋅ 10−4 ± 2 ⋅ 10−5 cm. For comparison to the corresponding cLogPs (Fig. 4 C), the s were converted to dimensionless partition coefficients ( where is the bilayer thickness, 4.5 nm; Lewis and Engelman, 1983). The cLogP estimates were consistently higher than the measured values. The difference between cLogP and varied between 0.2 for alaproclate and 1.3 for zimelidine (Table 2).

Table 2. AD surface densities and mole fractions in the bilayer and the actual aqueous concentrations required to double the fluorescence quench rate.

| Estimated usingK1 | Estimated using cLogP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | DAD | LogK1 | cLogP | {AD}L | mAD | [AD]W | {AD}L | mAD | [AD]W |

| μM | moles/cm2 | μM | moles/cm2 | μM | |||||

| Fluoxetine | 17 | 3.61 | 4.27 | 5.5⋅10−12 | 0.023 | 8.7 | 9.0⋅10−12 | 0.037 | 3.5 |

| Paroxetine | 30 | 3.35 | 3.68 | 6.7⋅10−12 | 0.028 | 20 | 9.7⋅10−12 | 0.040 | 15 |

| Sertraline | 31 | 4.51 | 5.18 | 17⋅10−12 | 0.068 | 5.4 | 20⋅10−12 | 0.078 | 1.6 |

| Amitriptyline | 53 | 3.59 | 4.72 | 14⋅10−12 | 0.056 | 32 | 29⋅10−12 | 0.11 | 9.0 |

| Imipramine | 82 | 3.31 | 3.71 | 14⋅10−12 | 0.057 | 61 | 21⋅10−12 | 0.084 | 50 |

| Fluvoxamine | 84 | 2.61 | 3.04 | 5.0⋅10−12 | 0.021 | 76 | 9.9⋅10−12 | 0.041 | 69 |

| Alaproclate | 220 | 2.43 | 2.58 | 8.0⋅10−12 | 0.033 | 210 | 10⋅10−12 | 0.042 | 200 |

| Citalopram | 250 | 2.64 | 3.39 | 12⋅10−12 | 0.050 | 230 | 30⋅10−12 | 0.12 | 200 |

| Zimelidine | 290 | 2.40 | 3.69 | 9.3⋅10−12 | 0.039 | 280 | 24⋅10−12 | 0.092 | 250 |

| Clomipramine | 39 | 5.29 | 25⋅10−12 | 0.096 | 1.7 | ||||

| Lofepramine | 42 | 6.26 | 28⋅10−12 | 0.11 | 0.2 | ||||

| Protriptyline | 52 | 4.70 | 29⋅10−12 | 0.11 | 9.0 | ||||

| Nortriptyline | 61 | 4.76 | 33⋅10−12 | 0.13 | 11 | ||||

| Trimipramine | 72 | 4.98 | 41⋅10−12 | 0.15 | 10 | ||||

| Dothiepin | 83 | 4.65 | 41⋅10−12 | 0.15 | 22 | ||||

| Desipramine | 97 | 4.28 | 37⋅10−12 | 0.14 | 41 | ||||

| Doxepin | 160 | 4.27 | 50⋅10−12 | 0.18 | 85 | ||||

{AD}L, mAD and [AD]W were calculated from Eqs. S29–S31 using either the experimental () or estimated () adsorption coefficients, where cLogP is the consensus value from the ACD/Percepta PhysChem Suite. = 1.5 ml, = 37.3 μmol, = 0.7 nm2, d0 (the DC22:1PC bilayer phosphate to phosphate thickness, 4.5 nm; Lewis and Engelman, 1983), and = 0.3 nm2.

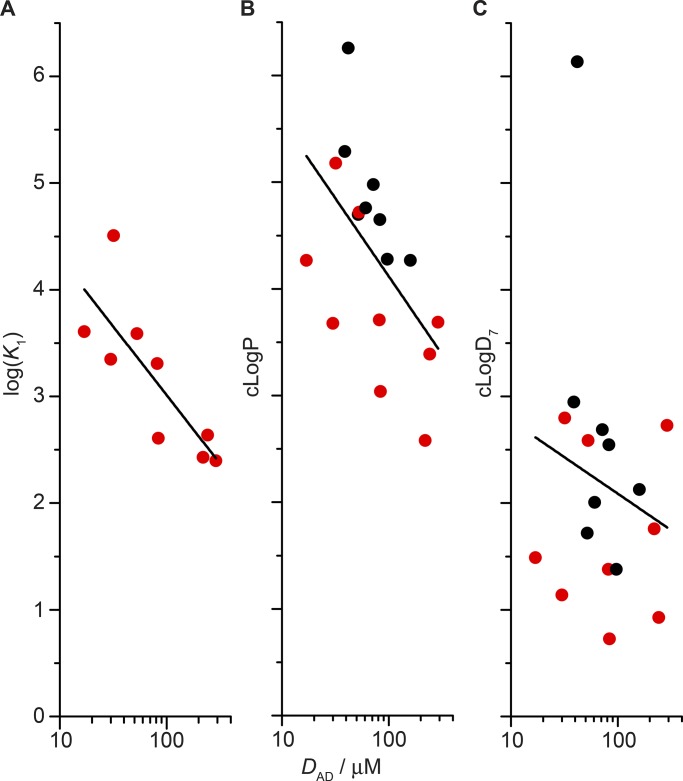

cLogP is thought to provide a good estimate of the bilayer partition coefficient (at least for neutral solutes; Avdeef, 2001; Seydel, 2002). The TCAs and SSRIs, however, are amines that, except for lofepramine (pKa = 6.5), have at least one amine group with a basic pKa (Table S2) and thus are charged at pH 7.0 (Fisar, 2005). To describe the distribution of titratable compounds into octanol (as a proxy for biological membranes; e.g., Wimley and White, 1996), it has been proposed one could use , the calculated octanol/water partition coefficient taking into account the aqueous distribution between charged and neutral species at the given pH (Bhal et al., 2007). The relationship between the ADs’ bilayer-modifying potencies and these different measures of hydrophobicity (partition coefficients) is explored in Fig. 5, where we plot the logarithm of the drug concentration needed to double the fluorescence quench rate (logDAD) versus logK1, cLogP, or cLogD7 (cLogDpH at pH 7.0).

Figure 5.

Comparing the bilayer-modifying potency of ADs with different measures of hydrophobicity (logK1 in A, cLogP in B, and cLogD7 in C). The subset of drugs that were tested using ITC are highlighted in red. (A) The slope of the straight line fit to logK1 versus log(DAD): −1.28 ± 0.35 (R2 = 0.60). (B) The slope of the straight line fit to cLogP versus log(DAD): −1.46 ± 0.58 (R2 = 0.25). Without lofepramine, the slope is −1.24 ± 0.50 (R2 = 0.25). (C) Slope of the straight line fit to cLogD7 versus log(DAD): −0.68 ± 0.92 (R2 = 0.02). Without lofepramine, the slope is −0.016 ± 0.55 (R2 = 0.06). The values for cLogP and cLogD7 are from the ACD/Percepta PhysChem Suite (2012).

There is an approximately linear correlation between logK1 and logDAD, and between cLogP and logDAD (though the scatter in the latter makes cLogP a poor predictor of bilayer-modifying potency) and no correlation between cLogD7 and logDAD, suggesting that a key determinant of an AD’s bilayer-modifying effect is its mole fraction in the membrane. The outlier with cLogP >6 in Fig. 5 B and cLogD7 >6 in Fig. 5 C is the TCA lofepramine. Excluding lofepramine did not change any conclusions.

The results in Fig. 5 (A and B) suggest that the ADs’ bilayer-modifying effects depend on their mole fraction in bilayer, with relatively little dependence on their molecular structure, similar to previous studies with aliphatic alcohols (Ingólfsson and Andersen, 2011; Zhang et al., 2018). That cLogD7 provides such poor predictive ability (Fig. 5 C) suggests that the assumption underlying estimates of cLogDpH (i.e., that the charged form of a titratable amphiphile does not partition into a hydrophobic phase) does not extend to the bilayer–solution interface, where the charged groups may reside in the interface. This is also evident in Fisar (2005) and our ITC results, even if the un-ionized form has a higher partition coefficient than the ionized/protonated form (Froud et al., 1986; Peitzsch and McLaughlin, 1993).

The association between bilayer-modifying potency and partitioning into the bilayer was further explored by calculating the AD surface density {AD}L and the mole fraction (mAD) in the bilayer, along with the actual [AD]W at the nominal DAD in the experiments (Bruno et al., 2007; Ingólfsson et al., 2007; Rusinova et al., 2011; Eqs. S29–S31). The results (at [AD]nom = DAD) are summarized in Table 2.

The ITC-based K1 estimates of mAD at DAD ranged between 0.02 and 0.07, indicating that there is less than one AD in the first shell of lipids around the channel (there are 8–10 lipid molecules in the first shell; Kim et al., 2012; Beaven et al., 2017); the cLogP-based estimates varied widely, ranging from 0.04 to 0.18. For either estimate, the actual aqueous drug concentrations were up to sixfold less than the nominal concentration due to drug redistribution between the aqueous solution and the membrane.

Single-channel experiments

We tested two TCAs, amitriptyline and imipramine, and two enantiomeric pairs of two SSRIs, fluoxetine and citalopram, using gA single-channel electrophysiology (Ingolfson et al., 2008; Kapoor et al., 2008). DOPC/n-decane bilayers were doped with two gA analogues: the 15-amino-acid right-handed AgA(15) and the 13-amino-acid left-handed gA−(13). The opposite handedness prevents heterodimerization, and the homodimeric channels can be distinguished by their characteristic single-channel current transition amplitudes, as shown in the single-channel current traces and current transition amplitude histograms in Fig. 6 (A and B).

Addition of amitriptyline to both sides of the bilayer shifted the equilibrium between gA monomers and conducting dimers toward the conducting dimers in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A). The current transition amplitude histograms (Fig. 6 B) show that amitriptyline produced a concentration-dependent increase in channel appearance rate and a decrease in the current transition amplitude for both the short gA−(13) and the long AgA(15) channels. All the TCAs and SSRIs thus tested decreased the current transition amplitude for both channel types (see also Fig. S2). The single-channel survivor histograms were fit by single-exponential decays (Fig. 6, C and D) and show that amitriptyline increased the gA channel lifetime without introducing new, kinetically distinct channel forms. That amitriptyline causes a distinct shift in single-channel properties of both the left- and right-handed gA channels, with no evidence for multiple channel populations (within each of the two channel types), suggests that amitriptyline does not interact directly with the conducting channels.

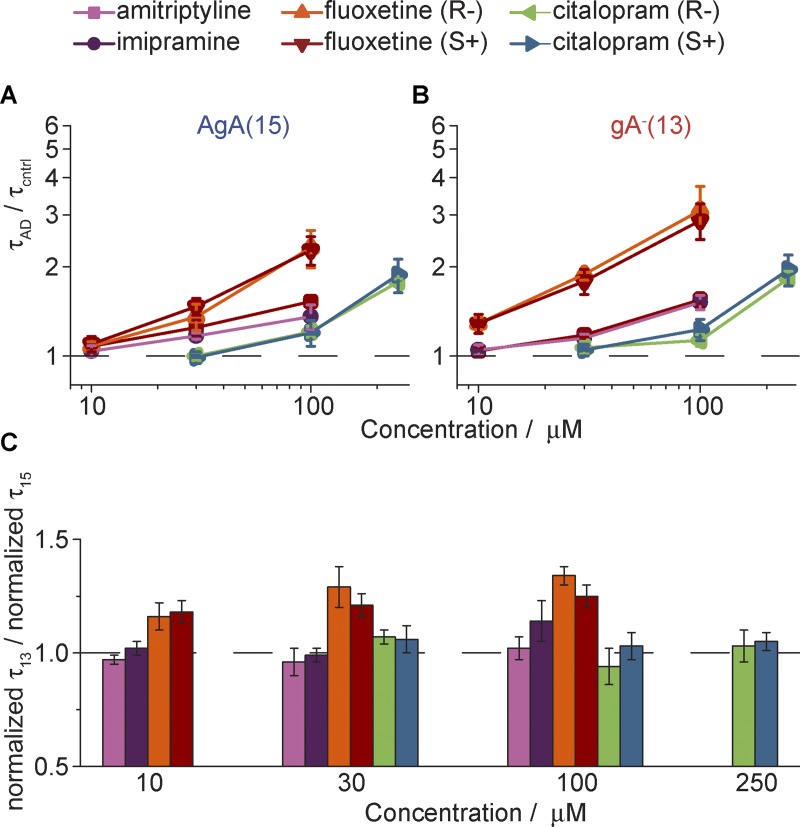

Consistent with the results of the fluorescence experiments, the tested compounds shifted the gA monomer↔dimer equilibrium toward the conducting dimers. The changes in single-channel lifetimes, normalized to the lifetimes in the absence of the drug (in the same experiment), are summarized in Fig. 7 (A and B).

Figure 7.

Summary of effects of ADs on gA channel activity in the single-channel assay. (A and B) Normalized (A) AgA(15) and (B) gA−(13) lifetimes, τAD,15/τcntrl,15 and τAD,13/τcntrl,13, respectively, with increasing concentration of the given AD. The colors represent different ADs: amitriptyline (purple), imipramine (pink), fluoxetine (S+; red), fluoxetine (R−; orange), citalopram (S+; blue), citalopram (R−; green).. (C) The ratio of normalized gA−(13) versus the normalized AgA(15) single-channel lifetimes at different drug concentrations. A ratio >1 (denoted by the dashed line) indicates a greater effect on channels formed by the shorter gA analogue by the given drug at that concentration. Values represent mean ± SE; n = 3–4.

The fluoxetine enantiomers had the greatest effect on gA channel lifetimes for both long AgA(15) (τAD,15/τcntrl,15) and short gA–(13) (τAD,13/τcntrl,13) channels (τAD,15/τcntrl,15 = 2.3 ± 0.3 and 2.3 ± 0.3, and τAD,13/τcntrl,13 = 2.9 ± 0.4 and 3.1 ± 0.6 at 100 µM fluoxetine [S+] and [R−]). Imipramine and amitriptyline had less effect on gA channel lifetimes (τAD,15/τcntrl,15 = 1.4 ± 0.1 and 1.5 ± 0.1, and τAD,13/τcntrl,13 = 1.5 ± 0.1 and 1.6 ± 0.1 at 100 µM imipramine and amitriptyline). The citalopram enantiomers had the least effect (τAD,15/τcntrl,15 = 1.9 ± 0.2 and 1.78 ± 0.04, and τAD,13/τcntrl,13 = 2.0 ± 0.2 and 1.8 ± 0.1 at 250 µM citalopram [S+] and citalopram [R−]). There was no apparent stereospecificity, because the R enantiomers of fluoxetine and citalopram had similar effects on the AgA(15) and gA−(13) channel lifetimes, as did their S counterparts. The order of drug potency and the lack of enantiomer specificity agree with the results from the fluorescence quench assay.

Amitriptyline, imipramine, and the citalopram enantiomers had similar effects on the two gA channel types. That is, the drug-induced changes in τ did not vary with changes in the channel–bilayer hydrophobic mismatch (l – d0). The two fluoxetine enantiomers, however, had greater effects on the shorter gA−(13) channels, with the greater hydrophobic mismatch, than on the longer AgA(15) channels (Fig. 7 C).

The implications of this different dependence on hydrophobic mismatch were explored using the theory of elastic bilayer deformations (Huang, 1986; Nielsen et al., 1998; Nielsen and Andersen, 2000; Rusinova et al., 2011). The deformation induced by the formation of the transmembrane channel, with its associated energetic cost, causes the bilayer to impose a disjoining force (Fdis) on the channel, which is the sum of contributions due to the hydrophobic mismatch and to the intrinsic curvature (Rusinova et al., 2011):

| (11) |

where HB and HX are phenomenological elastic coefficients that are functions of the bilayer material properties and channel radius and c0 the intrinsic curvature. The curvature-dependent contribution to Fdis does not depend on the channel–bilayer hydrophobic mismatch and will therefore be the same for channels of different lengths (e.g., the channels formed by AgA(15) and gA−(13)). The normalized changes in the lifetimes of the short gA−(13) (τAD,13/τcntrl,13) and the long AgA(15) (τAD,15/τcntrl,15) channels therefore can be expressed as (Lundbæk et al., 2010b; Rusinova et al., 2011; Bruno et al., 2013):

| (12) |

where l13 and l15 denote the lengths of the short gA−(13) channel (∼1.9 nm) and the long AgA(15) channel (∼2.2 nm). Using Eq. 12, we deduce that changes in bilayer elasticity will produce relatively greater changes in the lifetimes of the short gA−(13) channels (compared with the AgA(15) channels). When evaluating the drug-induced changes in HB, we find that 100 µM fluoxetine (S+) or (R−) decreases HB by ∼2.3 ± 0.5 kBT/nm2 and ∼3.0 ± 0.3 kBT/nm2 (HB for the unmodified bilayer is ∼22 kBT/nm2; Lundbæk et al., 2010b). 100 µM imipramine decreases HB by only ∼1.3 ± 0.9 kBT/nm2. The remaining three compounds had negligible effects at their highest tested concentrations and would, within the framework provided by the theory of elastic bilayer deformations, be deemed to primarily alter the intrinsic curvature (co).

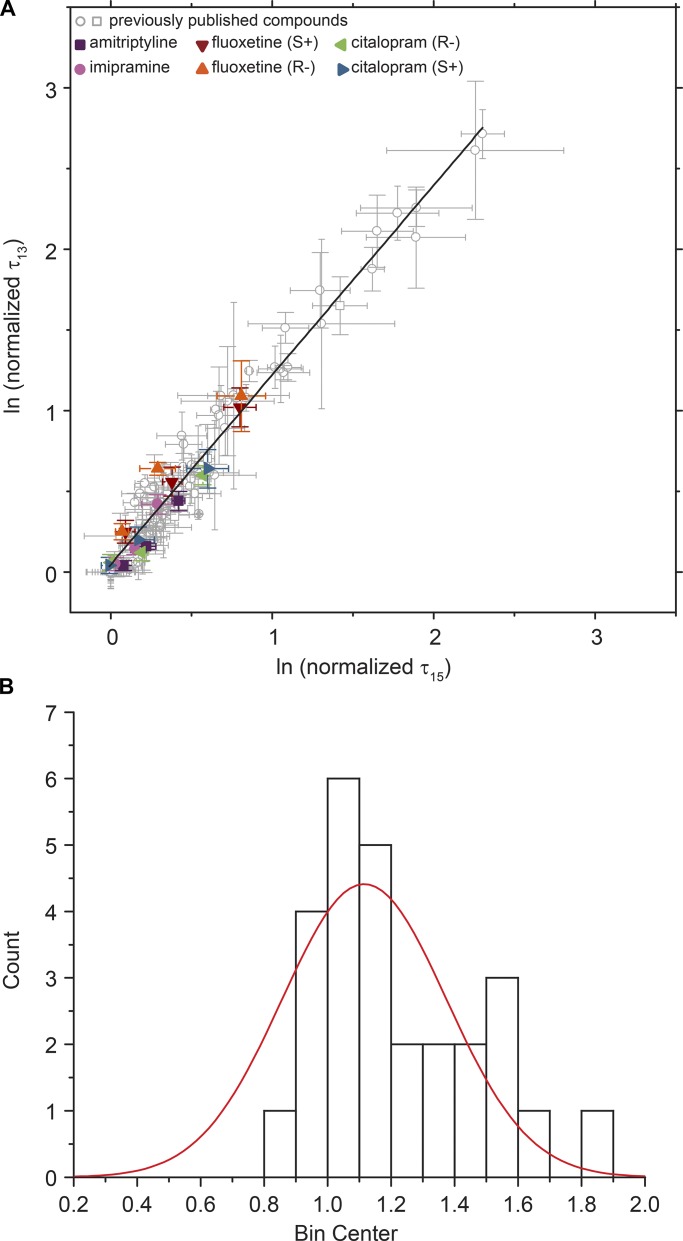

When considered as a group, the differential effects of ADs on the lifetimes of gA−(13) and AgA(15) channels are similar to those of other compounds (Lundbæk et al., 2010a; Rusinova et al., 2011, 2015; see Fig. 8). Fig. 8 A shows results for the ADs (colored symbols) as well as previously published results for other compounds (in gray).

Figure 8.

Comparing changes in gA−(13) lifetimes with AgA(15) lifetimes for a library of compounds. (A) Changes in gA−(13) channel lifetimes versus the corresponding changes in AgA(15) channel lifetimes. Gray dots represent previously published data (Lundbæk et al., 2010a; Rusinova et al., 2011, 2015); colored symbols represent different concentrations of the ADs amitriptyline (purple), imipramine (pink), fluoxetine (S+; red), fluoxetine (R−; orange), citalopram (S+; blue), citalopram (R−; green). Values are mean ± SE of ln(normalized τ); n ≥ 3. DC18:1PC/n-decane. Slope of the straight line fit is 1.17 ± 0.02, with residuals shown in Fig. S3. (B) Histogram of slopes from straight line fits to individual compounds where the maximum lifetime change is at least 150% of the control lifetimes for both gA–(13) and AgA(15) at maximum concentration. The width of the distribution suggests that some compounds alter bilayer properties other than elasticity. If fitted with a Gaussian distribution, the mean is 1.12, with a SD of 0.06.

The distribution of the slopes for the different compounds is shown in Fig. 8 B together with a Gaussian fit. The distribution of slopes suggest that the ADs alter lipid bilayer properties by a combination of thermodynamic softening (e.g., Evans et al., 1995; Zhelev, 1998; Bruno et al., 2013), which does not depend on molecular features (other than the drug’s partial molar area in the bilayer–solution interface), and more specific interactions with the bilayer-forming lipids.

Discussion

The TCA and SSRI families of ADs are promiscuous modifiers of membrane protein function (Table S1). We explored a possible mechanism for this promiscuity: that the amphiphilic ADs partition into lipid bilayers and thereby alter their properties. We find that the TCAs and SSRIs indeed alter lipid bilayer properties, as demonstrated by their effects on gA channel activity. These changes were observed with gA channels of opposite handedness and drugs of opposite chirality, effectively ruling out direct binding. This provides a mechanism for the ADs’ ability to alter the function of many different membrane proteins. Specifically, we show that these compounds reduce the lipid bilayer contribution to the free energy cost of membrane protein conformation transitions. The 21 tested compounds varied widely in their potencies to alter gA channel function, reflecting different partitioning into the bilayer and different intermolecular interactions in the bilayers. The relative potencies correlated with K1 (and cLogP), but not with cLogD7. Channel function increased twofold at a drug mole fraction in the bilayer of 0.02–0.07 (Table 2), corresponding to 0.2–0.7 drug molecules in the first lipid shell around the channels.

We first discuss the basis for how ADs alter lipid bilayer properties and the concentrations at which they do so. We finally consider briefly the implications for drug development.

The molecular basis for AD effects on bilayer properties

Amphiphiles may alter lipid physical properties (thickness, intrinsic curvature, and the associated elastic moduli) by at least three nonexclusive mechanisms. First, when amphiphiles intercalate into the bilayer interface, they will alter the profile of intermolecular forces across the bilayer (Seddon, 1990; Cantor, 1999), which in turn will lead to changes in acyl chain dynamics, elastic moduli, and intrinsic curvature (Helfrich, 1981). Second, the reversible partitioning of amphiphiles into the bilayer will increase the bilayer area, reduce the apparent elastic moduli (Evans et al., 1995; Zhelev, 1998), and most likely also thin the bilayer, because the increase in surface area is likely to occur without much increase in the volume of the hydrophobic core, which in turn will alter the intrinsic curvature (e.g., Israelachvili et al., 1977; Cullis and de Kruijff, 1979; Heerklotz and Blume, 2012). Third, in the case of membrane protein–induced deformations, the local bilayer deformation will lead to a redistribution of the amphiphiles in the vicinity of the protein (e.g., Bruno et al., 2007), which also will lead to an apparent softening (Andersen et al., 1992) or an increase in the thermodynamic elasticity (Evans et al., 1995; Zhelev, 1998).

The first mechanism involves the amphiphile’s detailed molecular structure and position in the bilayer. The second two mechanisms are thermodynamic in origin and therefore less dependent on the molecular structure. Whatever the (dominant) mechanism, however, it is unlikely that an amphiphile will alter only one bilayer property. The dihydrochalcone phloretin, for example, is a promiscuous modifier of membrane protein function that partitions into lipid bilayers to alter the interfacial dipole potential (Andersen et al., 1976), but it also increases the permeability to neutral solutes (Andersen et al., 1976) and the bilayer elasticity (Hwang et al., 2003). The changes in the gramicidin monomer↔dimer equilibrium (the changes in for the transition) reflect the aggregate effects of all the amphiphile-induced changes in bilayer properties (except for changes in fluidity, which do not alter ). It is possible to get insight into the underlying mechanisms, however, using the resolution provided by single-channel experiments (e.g., Fig. 8), which shows that even when amphiphiles are known to alter the intrinsic curvature, the changes in curvature may not be the quantitatively most important contributors to the changes in ; rather, the increase in the thermodynamic elasticity (compare Fig. 8) will in many cases become the dominant term (Lundbæk et al., 2005).

If all AD molecules had the same propensity to alter bilayer properties (per molecule in the membrane), and the differences in DAD only reflected different partitioning, then there should be a straight-line relationship between log(DAD) and logK1 with a slope of −1. The slopes of the fits to the logK1−log(DAD) and clogP−log(DAD) relations are indeed indistinguishable from −1, meaning that the relative bilayer-modifying potency of different ADs depends primarily on their relative partition coefficients into the bilayer. This conclusion is consistent with the results of Ingolfsson and Andersen (2011) and Zhang et al. (2018) on normal and fluorinated alcohols but in contrast with the results on a series of analogues of the snail toxin 6-bromo-2-mercaptotryptamine dimer, which showed no correlation between drug partitioning into the bilayer and their bilayer-modifying potency.

Many structurally unrelated compounds, such as detergents, lipid signaling molecules and metabolites, phytochemicals (Ingólfsson et al., 2007, 2011; Lundbæk et al., 2010b), alcohols (Ingólfsson and Andersen, 2011), and drugs (Rusinova et al., 2011, 2015; this study), produce similar changes in gA channel function. Given that gA channels are small, approximating smooth cylinders, it is unlikely that all of the above compounds have specific binding sites with similar affinities; rather, they exert their effects by altering lipid bilayer properties. Moreover these unrelated compounds have a commonality: they alter the function of both gA channels and integral membrane proteins (Lundbæk et al., 2010b), and the changes in membrane protein function can be related to the changes in gA channel function. This commonality arises despite the differences between the gA monomer↔dimer transition and the conformational changes that underlie the function of integral membrane proteins, indicating that both gA channels and integral membrane proteins respond to similar changes in lipid bilayer properties.

Despite the gA channels’ simplicity, their energetic coupling to their host bilayer is complex, as highlighted by the differential effects of amphiphiles on elasticity versus curvature in single-channel electrophysiology experiments using gA channels of different lengths. In the case of the fluoxetine enantiomers, we observed greater effect on the channel with greater hydrophobic mismatch, meaning they altered bilayer elasticity. In contrast, for amitriptyline, imipramine, and the citalopram enantiomers, we observed similar effects on gA channels irrespective of their length, suggesting that they primarily altered intrinsic curvature.

Following Evans et al. (1995), amphiphiles will be expected to increase bilayer elasticity for thermodynamic reasons. Indeed, most compounds tested to date have a dominant effect on elasticity, as shown by the slope of >1 when comparing normalized lifetimes of short and long channels (Fig. 8 A), though the distribution of slopes (Fig. 8 B) suggests that molecular features also are important. This is also likely to be true for amitriptyline, imipramine, and citalopram, where the dominant changes in bilayer properties appear to be curvature, an effect that is more dependent on the molecular features than on the amphiphilic nature of the compound per se. A compound’s effect on , and thus the bilayer contribution to the free energy of a membrane protein conformational change (Eq. 1), will depend on changes in both curvature and elasticity but with varying apportionment of the two properties. To further understand the molecular basis for these observations, one will need to examine a library of diverse and complex molecules in conjunction with computational and spectroscopic studies on the changes in lipid bilayer head group and acyl chain organization and dynamics.

AD concentrations

Micromolar concentration of TCAs and SSRIs are sufficient to alter the function of a transmembrane protein (the gA channel), at the concentrations where these drugs have promiscuous effects on many different channels. Given the simplicity of our experimental system, a single-component bilayer with a small yet very well-defined channel, one may question to what extent our conclusions extend to more complex systems. In this context it is important to note that there are no qualitative differences between our results in the single-component bilayers, which allow for detailed mechanistic interpretation, and our results in more complex membranes, in the presence of cholesterol (Bruno et al., 2007; Rusinova et al., 2011; Herold et al., 2014), or in membranes formed by so-called raft-forming mixtures (Herold et al., 2017). Moreover, it is possible to relate the amphiphile-induced changes in function of channels formed by integral membrane proteins, whether purified and reconstituted or expressed in cell membranes, to the corresponding changes in gA channel function in single-component bilayers (Lundbæk et al., 2004, 2005, 2010b; Søgaard et al., 2006, 2009; Rusinova et al., 2011; Herold et al., 2014, 2017; Ingólfsson et al., 2014). That is, though the gating mechanisms of channels formed by integral membrane proteins and gA channels are different, they are sensitive to the same changes in bilayer properties. In cases where there is no correlation between the effects in cells and in the gA-based assays (e.g., Herold et al., 2017; Dockendorff et al., 2018), the parsimonious interpretation becomes that the compounds alter membrane protein function by direct interactions or binding to their target.

Electrophysiological and transport studies involving more complex cellular membrane systems, which show that TCAs and SSRIs alter the function of large variety of membrane proteins (Table S1) at concentrations similar to those where the drugs alter gA channel function, thus need to be interpreted with caution. Though one cannot exclude that the changes in membrane protein function involve specific interactions (binding to a target protein), an alternative interpretation would be that at least a portion of the observed effects may reflect “nonspecific” drug–bilayer interactions (changes the contribution to ). Indeed, the parsimonious interpretation of results that demonstrate a promiscuous drug’s effects on multiple, unrelated membrane proteins’ function at similar concentration is that these effects reflect changes in the common feature shared by all membrane proteins: their host lipid bilayer.

Plasma concentrations of ADs are in the 0.1–1 µM range, with ∼90% being protein bound (DeVane, 1999; Gillman, 2007), which are less than the concentrations used in our and many other in vitro experiments. However, as has been demonstrated previously (Karson et al., 1993; Bolo et al., 2000), the concentration of fluvoxamine and fluoxetine in relevant therapeutic compartments, such as the brain, is 10- to 20-fold higher than plasma concentrations (up to 10 µM). Moreover, at clinically relevant concentrations, ΔGdef, and ergo the bilayer contribution to membrane protein function, though small, will be nonzero. Such small ΔGdef may be undetectable by our short-term assay but may nevertheless alter cell and system function when administered chronologically. For example, modifying less than ∼1% of voltage-dependent sodium channels with pyrethroid insecticides is sufficient to induce hyperexcitatory states (Narahashi, 1996).

Implications for AD drug development

The crystal structure of the biogenic amine transporter with a variety of compounds reveals a binding pocket where SSRIs and TCAs exert their inhibitory effects on these proteins (Wang et al., 2013). The drugs’ inhibitory effects (with Kis in the nanomolar range) on these proteins, however, do not provide the sole explanation for their clinical effects. Depression is increasingly modeled as a complex disease that is impacted by the immune system, hypothalamic–pituitary axis, neurotrophins, neurotransmitter changes, and synaptic and neural network plasticity, among other factors, all of which are targets for AD therapies (Tanti and Belzung, 2010; Duman et al., 2016).

In this context, it may be important that ADs are promiscuous drugs, and resolving the molecular basis for drug promiscuity may help guide drug development toward either a “magic bullet” (targeting one specific protein) or a “magic shotgun” (targeting multiple proteins; Roth et al., 2004; Hopkins et al., 2006; Bianchi and Botzolakis, 2010; Peters, 2013; Reddy and Zhang, 2013). Targeting multiple molecular pathways and networks, rather than individual proteins (i.e., exploiting drug promiscuity [or polypharmacology]) has proven advantageous (e.g., Ciceri et al., 2014), though the molecular properties that confer polypharmacological promise also may confer risk of toxicity (Peters, 2013). Polypharmacology can be achieved by different means, but a common feature of amphiphilic drugs is that they partition into the lipid bilayer/solution interface and thereby alter lipid bilayer properties. If the changes in bilayer properties are sufficiently large, then this is likely to cause toxicity; more modest changes may alter system function (Eger et al., 2008). The qualitatively different effects of fluoxetine and imipramine on the one hand and amitriptyline and citalopram on the other suggest that it may be possible to design molecules to target a bilayer property that may be important for a subset of membrane protein families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jens A. Lundbæk for suggesting that we examine the bilayer-modifying potential of ADs because they are such “dirty” drugs. We also thank Denise V. Greathouse, Helgi I. Ingólfsson, Kevin Lum, Radda Rusinova, and R. Lea Sanford for many helpful discussions along the way, as well as an anonymous reviewer for suggesting that we redo the original analysis of the ITC results. We thank Lundbeck A/S for their gift of the citalopram enantiomers and racemate.

This research was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health through grants R01 GM021342 and GM021342-35S1 (O.S. Andersen). R. Kapoor was supported by a Medical Scientist Training Program grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32GM007739 to the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan Kettering Tri-Institutional MD-PhD Program, as well as an Iris L. & Leverett S. Woodworth Medical Scientist Fellowship and a Richard Lounsberry Foundation Fellowship.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: R. Kapoor, O.S. Andersen, and R.E. Koeppe II participated in research design. R. Kapoor conducted experiments. T.A. Peyear and R.E. Koeppe II contributed new reagents or analytic tools. R. Kapoor and T.A. Peyear performed data analysis. R. Kapoor, O.S. Andersen, and R.E. Koeppe II wrote the manuscript.

José D. Faraldo-Gómez served as editor.

Footnotes

This work is part of the special collection entitled "Molecular Physiology of the Cell Membrane: An Integrative Perspective from Experiment and Computation."

References

- ACD/Percepta PhysChem Suite 2012. ACD/Percepta PhysChem Suite. Available at: https://www.acdlabs.com/products/percepta/ (accessed December 19, 2018).

- Andersen O.S., Finkelstein A., Katz I., and Cass A.. 1976. Effect of phloretin on the permeability of thin lipid membranes. J. Gen. Physiol. 67:749–771. 10.1085/jgp.67.6.749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen O.S., Sawyer D.B., and Koeppe R.E. II. 1992. Modulation of channel function by the host bilayer. In Biomembrane Structure and Function: The State of the Art. Gaber B.P., and Easwaran K.R.K., editors. Adenine Press, Schenectady, NY: 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Avdeef A. 2001. Physicochemical profiling (solubility, permeability and charge state). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 1:277–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard R., and Haydon D.A.. 1973. An Introduction to the Principles of Surface Chemistry. Cambridge University Press, London. [Google Scholar]

- Barsa J.A., and Sauders J.C.. 1961. Amitriptyline (Elavil), a new antidepressant. Am. J. Psychiatry. 117:739–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaven A.H., Maer A.M., Sodt A.J., Rui H., Pastor R.W., Andersen O.S., and Im W.. 2017. Gramicidin A Channel Formation Induces Local Lipid Redistribution I: Experiment and Simulation. Biophys. J. 112:1185–1197. 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmaker R.H., and Agam G.. 2008. Major depressive disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:55–68. 10.1056/NEJMra073096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberan-Santos M., Bodunov E., and Valeur B.. 2005. Mathematical functions for the analysis of luminescence decays with underlying distributions 1. Kohlrausch decay function (stretched exponential). Chem. Phys. 315:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bhal S.K., Kassam K., Peirson I.G., and Pearl G.M.. 2007. The Rule of Five revisited: applying log D in place of log P in drug-likeness filters. Mol. Pharm. 4:556–560. 10.1021/mp0700209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M.T. 2008. Non-serotonin anti-depressant actions: direct ion channel modulation by SSRIs and the concept of single agent poly-pharmacy. Med. Hypotheses. 70:951–956. 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M.T., and Botzolakis E.J.. 2010. Targeting ligand-gated ion channels in neurology and psychiatry: is pharmacological promiscuity an obstacle or an opportunity? BMC Pharmacol. 10:3 10.1186/1471-2210-10-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolo N.R., Hodé Y., Nédélec J.F., Lainé E., Wagner G., and Macher J.P.. 2000. Brain pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution in vivo of fluvoxamine and fluoxetine by fluorine magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 23:428–438. 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00116-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno M.J., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2007. Docosahexaenoic acid alters bilayer elastic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:9638–9643. 10.1073/pnas.0701015104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno M.J., Rusinova R., Gleason N.J., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2013. Interactions of drugs and amphiphiles with membranes: modulation of lipid bilayer elastic properties by changes in acyl chain unsaturation and protonation. Faraday Discuss. 161:461–480, discussion :563–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor R.S. 1999. Solute modulation of conformational equilibria in intrinsic membrane proteins: apparent “cooperativity” without binding. Biophys. J. 77:2643–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri P., Müller S., O’Mahony A., Fedorov O., Filippakopoulos P., Hunt J.P., Lasater E.A., Pallares G., Picaud S., Wells C., et al. 2014. Dual kinase-bromodomain inhibitors for rationally designed polypharmacology. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10:305–312. 10.1038/nchembio.1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullis P.R., and de Kruijff B.. 1979. Lipid polymorphism and the functional roles of lipids in biological membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 559:399–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVane C.L. 1999. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 19:443–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockendorff C., Gandhi D.M., Kimball I.H., Eum K.S., Rusinova R., Ingólfsson H.I., Kapoor R., Peyear T., Dodge M.W., Martin S.F., et al. 2018. Synthetic Analogues of the Snail Toxin 6-Bromo-2-mercaptotryptamine Dimer (BrMT) Reveal That Lipid Bilayer Perturbation Does Not Underlie Its Modulation of Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels. Biochemistry. 57:2733–2743. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman R.S., Aghajanian G.K., Sanacora G., and Krystal J.H.. 2016. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat. Med. 22:238–249. 10.1038/nm.4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger E.I. II, Raines D.E., Shafer S.L., Hemmings H.C. Jr., and Sonner J.M.. 2008. Is a new paradigm needed to explain how inhaled anesthetics produce immobility? Anesth. Analg. 107:832–848. 10.1213/ane.0b013e318182aedb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E.G., Rawicz W., and Hofmann A.F.. 1995. Lipid bilayer expansion and mechanical disruption in solutions of water soluble bile acid. In Bile Acids in Gastroenterology Basic and Clinical Advances. Hofmann A.F., Paumgartner G., and Stiehl A., editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fisar Z. 2005. Interactions between tricyclic antidepressants and phospholipid bilayer membranes. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 24:161–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froud R.J., East J.M., Rooney E.K., and Lee A.G.. 1986. Binding of long-chain alkyl derivatives to lipid bilayers and to (Ca2+-Mg2+)-ATPase. Biochemistry. 25:7535–7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman P.K. 2007. Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151:737–748. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse D.V., Koeppe R.E. II, Providence L.L., Shobana S., and Andersen O.S.. 1999. Design and characterization of gramicidin channels. Methods Enzymol. 294:525–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerklotz H., and Blume A.. 2012. Detergent interactions with lipid bilayers and membrane proteins. In Comprehensive Biophysics. Egelman E.H., editor. Elsevier, Oxford: 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Heerklotz H., and Seelig J.. 2000. Titration calorimetry of surfactant-membrane partitioning and membrane solubilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1508:69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich W. 1981. Amphiphilic mesophases made of defects. In Physique des défauts (Physics of defects). Balian R., Kléman M., and Poirier J-P. , editors. North-Holland Publishing Company, New York: 715-755. [Google Scholar]

- Herold K.F., Sanford R.L., Lee W., Schultz M.F., Ingólfsson H.I., Andersen O.S., and Hemmings H.C. Jr. 2014. Volatile anesthetics inhibit sodium channels without altering bulk lipid bilayer properties. J. Gen. Physiol. 144:545–560. 10.1085/jgp.201411172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold K.F., Sanford R.L., Lee W., Andersen O.S., and Hemmings H.C. Jr. 2017. Clinical concentrations of chemically diverse general anesthetics minimally affect lipid bilayer properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114:3109–3114. 10.1073/pnas.1611717114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse T.M., and Porter J.H.. 2015. A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 23:1–21. 10.1037/a0038550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A.L., Mason J.S., and Overington J.P.. 2006. Can we rationally design promiscuous drugs? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16:127–136. 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.W. 1986. Deformation free energy of bilayer membrane and its effect on gramicidin channel lifetime. Biophys. J. 50:1061–1070. 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83550-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.-C., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2003. Genistein can modulate channel function by a phosphorylation-independent mechanism: importance of hydrophobic mismatch and bilayer mechanics. Biochemistry. 42:13646–13658. 10.1021/bi034887y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolfson H., Kapoor R., Collingwood S.A., and Andersen O.S.. 2008. Single molecule methods for monitoring changes in bilayer elastic properties. J. Vis. Exp. (21):1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson H.I., and Andersen O.S.. 2010. Screening for small molecules’ bilayer-modifying potential using a gramicidin-based fluorescence assay. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 8:427–436. 10.1089/adt.2009.0250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson H.I., and Andersen O.S.. 2011. Alcohol’s effects on lipid bilayer properties. Biophys. J. 101:847–855. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson H.I., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2007. Curcumin is a modulator of bilayer material properties. Biochemistry. 46:10384–10391. 10.1021/bi701013n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson H.I., Sanford R.L., Kapoor R., and Andersen O.S.. 2010. Gramicidin-based fluorescence assay; for determining small molecules potential for modifying lipid bilayer properties. J. Vis. Exp. (44):2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson H.I., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2011. Effects of green tea catechins on gramicidin channel function and inferred changes in bilayer properties. FEBS Lett. 585:3101–3105. 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingólfsson H.I., Thakur P., Herold K.F., Hobart E.A., Ramsey N.B., Periole X., de Jong D.H., Zwama M., Yilmaz D., Hall K., et al. 2014. Phytochemicals perturb membranes and promiscuously alter protein function. ACS Chem. Biol. 9:1788–1798. 10.1021/cb500086e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili J.N., Mitchell D.J., and Ninham B.W.. 1977. Theory of self-assembly of lipid bilayers and vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 470:185–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor R., Kim J.H., Ingolfson H., and Andersen O.S.. 2008. Preparation of artificial bilayers for electrophysiology experiments. J. Vis. Exp. (20):1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karson C.N., Newton J.E., Livingston R., Jolly J.B., Cooper T.B., Sprigg J., and Komoroski R.A.. 1993. Human brain fluoxetine concentrations. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 5:322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer B., Neumcke B., and Läuger P.. 1971. Transport mechanism of hydrophobic ions through lipid bilayer membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 5:225–245. 10.1007/BF01870551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T., Lee K.I., Morris P., Pastor R.W., Andersen O.S., and Im W.. 2012. Influence of hydrophobic mismatch on structures and dynamics of gramicidin a and lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 102:1551–1560. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R. 1958. The treatment of depressive states with G 22355 (imipramine hydrochloride). Am. J. Psychiatry. 115:459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.G. 1991. Lipids and their effects on membrane proteins: evidence against a role for fluidity. Prog. Lipid Res. 30:323–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B.A., and Engelman D.M.. 1983. Lipid bilayer thickness varies linearly with acyl chain length in fluid phosphatidylcholine vesicles. J. Mol. Biol. 166:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbæk J.A., Birn P., Hansen A.J., Søgaard R., Nielsen C., Girshman J., Bruno M.J., Tape S.E., Egebjerg J., Greathouse D.V., et al. 2004. Regulation of sodium channel function by bilayer elasticity: the importance of hydrophobic coupling. Effects of Micelle-forming amphiphiles and cholesterol. J. Gen. Physiol. 123:599–621. 10.1085/jgp.200308996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbæk J.A., Birn P., Tape S.E., Toombes G.E.S., Søgaard R., Koeppe R.E. II, Gruner S.M., Hansen A.J., and Andersen O.S.. 2005. Capsaicin regulates voltage-dependent sodium channels by altering lipid bilayer elasticity. Mol. Pharmacol. 68:680–689. 10.1124/mol.105.013573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbæk J.A., Collingwood S.A., Ingólfsson H.I., Kapoor R., and Andersen O.S.. 2010b Lipid bilayer regulation of membrane protein function: gramicidin channels as molecular force probes. J. R. Soc. Interface. 7:373–395. 10.1098/rsif.2009.0443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbæk J.A., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2010a Amphiphile regulation of ion channel function by changes in the bilayer spring constant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:15427–15430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannhold R., Poda G.I., Ostermann C., and Tetko I.V.. 2009. Calculation of molecular lipophilicity: State-of-the-art and comparison of log P methods on more than 96,000 compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 98:861–893. 10.1002/jps.21494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S., and Harary H.. 1976. The hydrophobic adsorption of charged molecules to bilayer membranes: a test of the applicability of the stern equation. Biochemistry. 15:1941–1948. 10.1021/bi00654a023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S., Khelashvili G., Shan J., Andersen O.S., and Weinstein H.. 2011. Quantitative modeling of membrane deformations by multihelical membrane proteins: application to G-protein coupled receptors. Biophys. J. 101:2092–2101. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M.J., Bastos M., and Velazquez-Campoy A.. 2010. Partition of amphiphilic molecules to lipid bilayers by isothermal titration calorimetry. Anal. Biochem. 399:44–47. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. 1996. Neuronal ion channels as the target sites of insecticides. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 79:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C., and Andersen O.S.. 2000. Inclusion-induced bilayer deformations: effects of monolayer equilibrium curvature. Biophys. J. 79:2583–2604. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76498-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C., Goulian M., and Andersen O.S.. 1998. Energetics of inclusion-induced bilayer deformations. Biophys. J. 74:1966–1983. 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77904-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitzsch R.M., and McLaughlin S.. 1993. Binding of acylated peptides and fatty acids to phospholipid vesicles: pertinence to myristoylated proteins. Biochemistry. 32:10436–10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.-U. 2013. Polypharmacology - foe or friend? J. Med. Chem. 56:8955–8971. 10.1021/jm400856t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammes G., and Rupprecht R.. 2007. Modulation of ligand-gated ion channels by antidepressants and antipsychotics. Mol. Neurobiol. 35:160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantamäki T., and Yalcin I.. 2016. Antidepressant drug action--From rapid changes on network function to network rewiring. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 64:285–292. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A.S., and Zhang S.. 2013. Polypharmacology: drug discovery for the future. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 6:41–47. 10.1586/ecp.12.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth B.L., Sheffler D.J., and Kroeze W.K.. 2004. Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3:353–359. 10.1038/nrd1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinova R., Herold K.F., Sanford R.L., Greathouse D.V., Hemmings H.C. Jr., and Andersen O.S.. 2011. Thiazolidinedione insulin sensitizers alter lipid bilayer properties and voltage-dependent sodium channel function: implications for drug discovery. J. Gen. Physiol. 138:249–270. 10.1085/jgp.201010529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinova R., Koeppe R.E. II, and Andersen O.S.. 2015. A general mechanism for drug promiscuity: Studies with amiodarone and other antiarrhythmics. J. Gen. Physiol. 146:463–475. 10.1085/jgp.201511470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon J.M. 1990. Structure of the inverted hexagonal (HII) phase, and non-lamellar phase transitions of lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1031:1–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig J., Nebel S., Ganz P., and Bruns C.. 1993. Electrostatic and nonpolar peptide-membrane interactions. Lipid binding and functional properties of somatostatin analogues of charge z = +1 to z = +3. Biochemistry. 32:9714–9721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydel J.K. 2002. Octanol-water partitioning versus partitioning into membranes. In Drug-Membrane Interactions: Analysis, Drug Distribution, Modeling. Seydel J.K., and Wiese M., editors. Wiley-VCH, Darmstad, Germany: 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard R., Werge T.M., Bertelsen C., Lundbye C., Madsen K.L., Nielsen C.H., and Lundbæk J.A.. 2006. GABA(A) receptor function is regulated by lipid bilayer elasticity. Biochemistry. 45:13118–13129. 10.1021/bi060734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard R., Ebert B., Klaerke D., and Werge T.. 2009. Triton X-100 inhibits agonist-induced currents and suppresses benzodiazepine modulation of GABA(A) receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1788:1073–1080. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchyna T.M., Tape S.E., Koeppe R.E. II, Andersen O.S., Sachs F., and Gottlieb P.A.. 2004. Bilayer-dependent inhibition of mechanosensitive channels by neuroactive peptide enantiomers. Nature. 430:235–240. 10.1038/nature02743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A., Ziegler A., Steinbauer B., and Seelig J.. 2002. Thermodynamics of sodium dodecyl sulfate partitioning into lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 83:1547–1556. 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73924-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanti A., and Belzung C.. 2010. Open questions in current models of antidepressant action. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159:1187–1200. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00585.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Goehring A., Wang K.H., Penmatsa A., Ressler R., and Gouaux E.. 2013. Structural basis for action by diverse antidepressants on biogenic amine transporters. Nature. 503:141–145. 10.1038/nature12648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk M.R., and Seelig J.. 1997. Interaction of octyl-beta-thioglucopyranoside with lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 73:2565–2574. 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78285-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimley W.C., and White S.H.. 1996. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:842–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Peyear T., Patmanidis I., Greathouse D.V., Marrink S.J., Andersen O.S., and Ingólfsson H.I.. 2018. Fluorinated Alcohols’ Effects on Lipid Bilayer Properties. Biophys. J. 115:679–689. 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhelev D.V. 1998. Material property characteristics for lipid bilayers containing lysolipid. Biophys. J. 75:321–330. 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77516-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.