Abstract

The lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) forms nanoscopic clusters in cell plasma membranes; however, the processes determining PIP2 mobility and thus its spatial patterns are not fully understood. Using super-resolution imaging of living cells, we find that PIP2 is tightly colocalized with and modulated by overexpression of the influenza viral protein hemagglutinin (HA). Within and near clusters, HA and PIP2 follow a similar spatial dependence, which can be described by an HA-dependent potential gradient; PIP2 molecules move as if they are attracted to the center of clusters by a radial force of 0.079 ± 0.002 pN in HAb2 cells. The measured clustering and dynamics of PIP2 are inconsistent with the unmodified forms of the raft, tether, and fence models. Rather, we found that the spatial PIP2 distributions and how they change in time are explained via a novel, to our knowledge, dynamic mechanism: a radial gradient of PIP2 binding sites that are themselves mobile. This model may be useful for understanding other biological membrane domains whose distributions display gradients in density while maintaining their mobility.

Introduction

Although the lateral organization of proteins and lipids (clustering) in the cell plasma membrane (PM) is crucial to diverse fundamental cellular processes, there is considerable disagreement on the organizational mechanisms that govern such clustering, e.g., 1) confinement by cytoskeleton-based fences (1), 2) protein-specific partitioning into liquid-ordered lipid rafts (2), or 3) tethering of groups of molecules to the underlying actin cytoskeleton (3), among others. One reason a mechanistic understanding of the organizing principles has remained elusive is that such nanoscale molecular assemblies are highly dynamic, requiring recordings of individual molecules at higher temporal bandwidth than hitherto possible to gain a better understanding of the physicochemical principles that regulate membrane clustering. In addition to physiological processes, the pathophysiological basis of disease states is increasingly focused on clusters. Influenza A virus causes significant morbidity and mortality, especially during flu pandemics and epidemics (4, 5, 6, 7). The lipid envelope of influenza virus is obtained from cellular membranes before viral budding from the cell, and during this process, the viral glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase are inserted into the viral envelope (8). HA localized to the PM of host cells clusters spontaneously (9, 10, 11) and is crucial for fusion, viral budding, and infection (12); high HA density on resultant virions is needed for entry into and fusion with the next host cell (13). Yet even this model system generates conflicting data on the mechanism of lipid clustering with HA—there is not even qualitative agreement as to which lipids cocluster with HA (14, 15, 16, 17, 18).

Because of the reliance of HA on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)-mediated actin comets for transport from the Golgi to the PM (19) and because HA clustering depends on underlying cortical actin (9), we hypothesized that PIP2 is itself the crucial lipid nexus between the PM, the actin cytoskeleton, and HA. HA also has multiple basic residues and palmitoylation sites in its cytoplasmic tail (CT) (20), which are known to play a role in phosphoinositide interactions (21, 22, 23, 24) and membrane association (21, 22). PIP2 has a regulatory role in the three-dimensional landscape of proteins, signaling pathways, and physiological processes in the cell (25, 26, 27, 28), and it binds to and regulates a host of membrane proteins, including gated ion channels (29, 30). Through modulation of adhesions between the cortical actin cytoskeleton and the PM (31), PIP2 can dynamically control function (23, 24). Key to this functional diversity is exquisite control of the spatial patterning of PIP2 at the PM (25). Early findings show PIP2 is sequestered in membrane domains (32), clustered on the nanoscale (33, 34), and confined within fences in phagosomes of macrophages (35) and has the ability to drive clustering of proteins in model membranes (36). However, PIP2 imaging with electron microscopy (37) and some super-resolution single-molecule imaging studies have indicated homogeneous PIP2 distributions in the PM (38). Thus, the mechanisms controlling clustering of lipids and proteins within the PM remain controversial. Key gaps in our understanding of PIP2 organization include the following questions: 1) how is the nanoscale distribution of PIP2 regulated in the PM and 2) does the intracellular HA-PIP2 relationship extend to the PM?

The interactions between actin, myosin, membrane-associated proteins, and lipids have been postulated to explain dynamic nanoscale membrane clustering (39) and have been implicated in influenza infection (9, 40, 41, 42). As previously established, portions of the cortical actin cytoskeleton are colocalized with HA clusters and can mediate the lateral mobility of HA in the PM (9). Because of the known role of PIP2 in control of the actin cytoskeleton (25, 26), we decided to first test the hypothesis that PIP2 clusters with HA in the PM; we found that it does. The major hypotheses on membrane cluster formation are then tested by measuring thousands of individual molecular trajectories of PIP2 on the PM and their dependence on HA. Finally, we present a dynamic gradient model to explain the organization of HA and PIP2 in space and time.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, staining, and immunofluorescence

NIH-3T3 and NIH-3T3-HAb2 (hereafter referred to as HAb2) cells were cultured as described (9). Cells were plated onto randomly assigned #1.5 glass coverslips (Corning, New York, NY) in six-well plates (353046; Falcon (New York, NY)/Corning) seeded at a density of 3–5 × 103/cm2 and grown to ∼80% confluence for imaging. All live-cell experiments were done with a stage-mounted incubator (Tokai Hit, Fujinomiya, Japan) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 20 mM D-glucose.

Labeling with GloPIP (BODIPY TMR-Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; C45M16a; Echelon Biosciences, San Jose, CA) used the Shuttle PIP kit (P-9035; Echelon Biosciences) and followed the manufacturer’s instructions, which are based on methods described elsewhere (43) (see specifically details for use of histones as carriers). Briefly, GloPIP was stored at −20°C and the Histone H1 carrier at 4°C. Before use, all elements were warmed to room temperature. GloPIP and the carrier were then diluted to a final concentration of 100 and 200 nM, respectively, in complete media. For cell labeling, NIH-3T3 cells were removed from the incubator and checked under a light microscope for normal morphology. The cell medium was removed, and 500 μL of (GloPIP + carrier) solution was added to each well. A control was also made containing 500 μL of 200 nM carrier in solution but without GloPIP. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 45 min. Before imaging, the cells were removed from the incubator, the medium containing the GloPIP and carrier was removed, cells were washed with PBS, and 500 μL of PBS + glucose without GloPIP and without carrier was added.

Super-resolution fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy

Samples were imaged according to methods published previously (9, 44, 45). The experimental setup was an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) IX71 inverted microscope with 60 × 1.45 NA total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy objective lens, 2× telescope in the detection path, and an Andor iXon + electron multiplying charge couple device (DU897-DCS-BV; Andor, Belfast, UK). Excitation was performed using a 561 nm laser (Sapphire; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) and activation using 405 nm (FBB-405-050-FSFS-100; RGBlase LLC, Fremont, CA) in either widefield or total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) illumination. Lasers were combined using a dichroic (Z405RDC; Chroma, Rockingham, VT), then steered into a +350 mm convex lens (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) at one focal length from the objective back aperture plane. FPALM images were typically acquired with a frame rate of 30–50 Hz and electron multiplication gain of 200. For Dendra2-and GloPIP single-color data, the detection filters included either a T565LP (Chroma) or a 561RU dichroic (Semrock, Rochester, NY), a 405 nm and two 561 notch filters (NF03-405E-25 and NF561E-25; Semrock), and a 605/70 emission filter (Chroma). The collected data were then analyzed for molecular identification and localization using custom MATLAB software (The MathWorks, Natick, MA), which fitted individual molecules to a two-dimensional Gaussian to be tracked through consecutive frames using a nearest-neighbor algorithm. Samples labeled with GloPIP were imaged at 7 ms/frame for 5000–40,000 frames, illuminated with a 561 nm readout beam at intensities of ∼0.5 kW/cm2. Acquired camera frames were processed according to standard algorithms for identification and localization of individual emitters (9).

Multicolor super-resolution microscopy

Experiments followed previously published methods (9, 45). In addition to the 405 and 561 nm lasers, for Alexa647-labeled samples, a HeNe laser (632.8 nm) was also aligned through the illumination path to be co-linear with the other beams. The filters and dichroics used were as follows: dichroic in the microscope turret, DiO1R 405/488/561/635 (Semrock); notch filters in detection path (2 × 405 nm, 2 × 561 nm, 1 × 633 nm; all Semrock); dichroic in the two-color detection module, FF580-FDi01 (Semrock); emission filter in the red channel, a Brightline 664 LP (Semrock), and in the orange channel, an FF-01 585/40 (Semrock). The same filters were used for Dendra2/PAmKate, except that the red emission filter was a Brightline 630/92 (Semrock) and the 633 nm notch filter was not used. For calibration and spatial alignment of the two emission channels, fluorescent beads (Tetraspeck microspheres, 0.1 μm; Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA)/ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA)) were imaged simultaneously in both emission channels. The images were then cross-correlated automatically using a previously described algorithm (9, 45) to determine the transformation that best aligned the two channels. After background subtraction using the rolling ball method (45, 46), localization of fluorophores was performed as usual with a pixel intensity threshold (typically 12–20 photons) for the merged pair of channels or using separate thresholds for each channel when one label was significantly brighter than the other (as for Alexa647 and Dendra2). Localizations were then screened for goodness of fit, number of photons per localization (within the range 10–3000 photons), point spread function width (1/e2 radius 140–600 nm), localization uncertainty (<80 nm), and error in fitted point spread function width (<150 nm) to exclude failed or poor fits. Localizations passing the tolerances were then drift corrected, and individual species were identified using cutoffs for α, the ratio of intensities of each localized spot in the red channel over the total intensity (red plus orange channels) (45). The cutoffs were determined using the measured α histograms for cells labeled with only one of the two species and imaged on the same day. Typically, Dendra2 was identified as α < 0.61, and PAmKate was identified as α > 0.63. Bleedthrough rates for this combination of probes were also estimated from the α histograms to be ∼3.6% (average for Dendra2 and PAmKate) and <1% for Dendra2 and Alexa647. The overall magnification of the microscope was measured on each measurement day using the image of a calibrated scale. The pixel-value-to-photon conversion factor was determined using previously published methods (46).

Trajectory and cluster analysis

Trajectories were calculated as previously described (9). Briefly, localizations in subsequent frames were connected together into a trajectory if and only if 1) the localization in the nth frame and the localization in the (n + 1)th frame differed in position by no more than 300 nm and 2) no more than one localization was observed within 300 nm of the given localization in either the nth frame or the (n + 1)th frame. These criteria were designed to reduce the probability that a given molecule could be confused with another nearby molecule in a given frame or in two temporally adjacent frames. Because there was a population of molecules outside of cells evident in TIRF imaging, we categorized this population as a background group that had adhered to coverslips without entering cells (“noncell” trajectories). To control for the possibility of molecules adhering to coverslips underneath cells contributing erroneously to data sets from within cells, we empirically characterized the mobility of noncell trajectories evident outside of imaged cell areas (i.e., on coverslips) and then identified trajectories from within imaged cell areas that matched the criteria of noncell trajectories. Trajectories that met all of the following conditions were removed from consideration: trajectory length ≥6 steps with a mean trajectory step length <0.08 μm and restricted to an area <0.175 μm2 (∼0.24 μm radius).

Cluster identification by SLCA

Clusters of HA and PIP2 were identified by single-linkage cluster analysis (SLCA) (9) using the following algorithm: starting with any individual molecule, all neighbors within a radial distance dmax were identified. All of these molecules, plus the initial one, were grouped into a cluster. The search was then repeated to find any additional molecules within dmax of any of those within the given cluster. The process was then repeated until no additional molecules were added to that cluster. The coordinates of molecules within each cluster were then quantified to obtain an area and density (number of molecules per unit area) for that cluster. The cluster area was obtained by convolving a plot of the individual molecular coordinates with a circle of radius dmax and then finding the total area of the contiguous shape. The cluster density was defined as the ratio of the number of localizations within a cluster divided by the area of that cluster.

For trajectory analysis comparing mobility inside of and outside of clusters, the density of localized molecules within the entire masked area of the imaged cell observed was used to calculate , where Φ is the average PIP2 density (number of localizations per unit area) for the given cell within the same 200 ms time window that the trajectory was observed. We used this value for dmax to account for potentially different levels of labeling of different clusters and/or cells.

Cluster identification by density plot

Clusters of HA or PIP2 were identified using the following algorithm: a rectangular grid of 10 × 10 nm pixels large enough to encompass all localizations for each cell was created. For each localization, the pixel value corresponding to the position of that localization was incremented. To account for localization errors, the grid was then convolved with a Gaussian of total area unity and 1/e2 width equal to 30 nm, approximately equivalent to the localization precision, and the HA (or PIP2) counts per pixel were then divided by the average HA (or PIP2) density within the cell to generate a relative density map of Drel, the density relative to the average for the cell. A boolean version of the density map was then created using a threshold for the minimal density Dmin of HA or PIP2 per unit area equal to four times the cell average. Grid pixels with Drel ≥ Dmin were assigned a value 1, and values Drel < Dmin were assigned a value 0. Clusters were then identified from the boolean density map as contiguous areas of value 1. Identified clusters were quantified for area and density using the MATLAB function regionprops. In total, data from 38 cells in five separate biological replicates were combined and analyzed. Clusters of at least 10 HA molecules were then considered for further analysis, and averages of the area and density of these clusters were calculated. Differences between the means of the PIP2 cluster area with low HA relative density (Drel < 0.05) and high HA (Drel > 5) were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test (two-tailed).

Comparison of measured probability density function to predictions of various confinement models

Confinement was measured using the potential models described in Jin et al. (47). First, a histogram H(r) of the number of particles as a function of r, the distance from the cluster center, is calculated. To match the form of Jin et al., the radial particle distribution function d(r) is then calculated using the histogram of the number of particles:

| (1) |

where a = π[(r + Δr)2 − (r − Δr)2]. The normalized particle distribution function (nPDF) is then

| (2) |

The normalized particle distribution function is also defined in terms of a potential V(r):

| (3) |

where

and kB is Boltzmann’s constant, T is the absolute temperature in the live-cell chamber (310 K), V0 is the strength of the potential, and rc is the confinement radius for the hardwall model. To find the appropriate confinement model, the equation is linearized with respect to r such that

| (4) |

where α = 1 for cone potential, α = 0.5 for spring potential, and α = 0.25 for the r4 potential. The appropriate model follows a linear relationship with distance r.

Calculation of turn angle histograms from molecular trajectories

Turn angles were measured as the angle between any two steps such that angles of all steps in all trajectories were calculated with respect to the previous step in the same trajectory. To address circular boundary conditions, polar coordinates of angles were converted to Cartesian coordinates (see (48) for more detail). From these, the mean turn angles per cell were calculated for each of five different diffusion rates and for two different conditions: either inside or outside of clusters (those trajectories that crossed the borders of clusters were not considered for turn angle analyses). Data were compared between inside and outside clusters using a χ2 goodness of fit test. Sets for each speed in each cell were compared by normalizing the data between outside and inside clusters (with n between 168 and 5947 steps in each set).

Generation of PH-dendra2 plasmid

GFP-C1-PLCδ-pleckstrin homology (PH) was gifted from Tobias Meyer of Stanford University (# 21179; Addgene plasmid, Watertown, MA) and was used as template for gene extraction. A YFP vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was utilized to generate a Dendra2 plasmid by replacement of the YFP gene with a Dendra2 gene (kind gift of Vladislav Verkhusha, Albert Einstein College of Medicine) using restriction enzymes NotI and BamHI. The PH-domain gene product was amplified by a 5′ primer containing HindIII site followed by 17 nucleotides of the open reading frame (PHDF, 5′-TTCAAGCTTATGG ACTCGGGCCGGGA-3′) and a 3′ primer complementary to the last 20 nucleotides of the open reading frame with a BamHI site in place of the stop codon (PHDR, 5′-ACAGGATCCACCTGGATGTT GAGCTCCT-3′; underlined letters show mutated stop codon). The PCR product was purified using a silica bead DNA gel extraction kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Both the product and vector were digested with HindIII and BamHI and gel purified using a silica bead DNA gel extraction kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). The product was ligated into the Dendra2 plasmid using T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen) such that Dendra2 was attached to the C-terminus of the PH domain as a fused protein. DH5α cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with PH-Dendra2 ligated plasmid and cultured overnight in Luria Bertani medium (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), followed by plasmid prep using a high-speed plasmid maxi prep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To confirm that the cloned construct fusion protein was in frame and was incorporated in the correct direction, sequencing was performed by The University of Maine DNA Sequencing Facility (The University of Maine, Orono, ME) using 100 ng of plasmid and 10 pmol of PH-domain primers (PHDF and PHDR) along with the reverse primer of the dendra2 gene, (Dendra2_R_628-651, 5′-GTGCTCGTACAGCTTCACCTTGTT-3′). Sequences were analyzed with FinchTV software (Version 1.4.0; Geospiza, Denver, CO).

Imaging of fluorescent protein-tagged PH-domain construct

HAb2 cells (passage 28 for widefield, passage 32 for TIRF) and NIH-3T3 cells (passage 45 for widefield, passage 26 for TIRF) were transfected with PH-Dendra2 and allowed to grow for 36–48 h post-transfection before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were imaged in 1× PBS with Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions. The PH-Dendra2 was activated with 405 nm laser (power at sample of 0.8–40 μW) and excited with 561 nm laser (power at sample of 3.71–7.05 mW).

Sample preparation for two-color FPALM

NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cells were transfected with a construct expressing Dendra2-HA and PAmKate-PH (the PH domain from PLCδ) using the Lipofectamine 3000 transfection kit (ThermoFisher). Afterward, cells were incubated in cell media at 37°C for 36 h before being washed three times with 1× PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were subsequently washed three more times with 1× PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ and stored at 4°C for imaging at a later date.

Simulations of PIP2 dynamics and radial potential

PIP2 molecules were treated as particles diffusing in a two-dimensional area (i.e., the xy plane). Each particle was given a lateral step in both x and y, drawn from a Gaussian distribution with SD σ, where σ2 = 4Dτ, D is the diffusion coefficient, and τ is the time step. A total of 1000 particles were simulated for 5 × 105–106 time steps of τ = 10−6 s each. The particles had a probability per time step of becoming trapped that was linearly proportional to the density of HA and that was spatially dependent according to the measured density of HA (9) (see Results and Discussion) as a function of distance from the cluster center, here taken to be the coordinate origin. Trapped PIP2 molecules were assumed to move with the same diffusion coefficient as the HA trimer, namely D = 0.088 μm2/s (9), whereas free particles were assumed to move with the diffusion coefficient we measured using labeled PIP2: D = 1.13 μm2/s. The trap rate ktrap ranged from 0 to 2.9 × 105 s−1 in proportion to the spatial dependence of HA density (see Results and Discussion). Particles also could escape the trap with a rate of kesc = 1.5 × 104 s−1. Effects of intracellular ion concentrations, such as Mg2+, were ignored. A localization error with Gaussian distribution σ = 20 nm was added to exact molecular positions to yield a simulated measured position, which was then recorded for each time step; from these positions, H(r) was then calculated. The potential V(r) was then calculated from d(r) using Eq. 3 rearranged to

| (5) |

The trap rates were adjusted to yield a bound fraction of PIP2 (fbound) consistent with the average measured diffusion behavior for PIP2 in cells containing HA (fbound = 0.4) and a cluster size consistent with measurements.

Results and Discussion

Because HA is a viral protein, all expression of HA is strictly speaking an overexpression; we use overexpression of HA to consider the effect of a single component of influenza virus on cell function and here, specifically, on the spatial distribution and dynamics of PIP2.

Super-resolution and confocal microscopy of HA and PIP2 in fixed cells

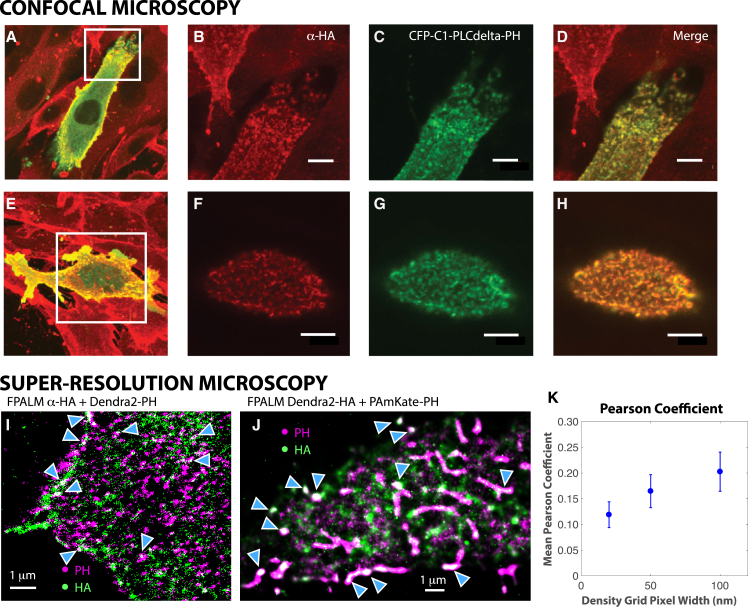

We first investigated whether HA and PIP2 are spatially correlated. Monolayers of NIH-3T3 cells stably overexpressing HA (A/Japan/305/57) from the H2N2 strain of human influenza virus (NIH-3T3-HAb2 cells (13, 49)) were transfected to transiently express a PH domain of phospho lipase C δ fused to CFP (PLCδ-PH-CFP (50)) to label PIP2 localization, then fixed and immunostained with a monoclonal antibody against HA. We then used super-resolution microscopy (fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy; FPALM) (51) to image the basal surfaces of NIH-3T3 cells expressing Dendra2-HA (A/Puerto Rico) and PAmKate-PH(PLCδ) or HAb2 cells expressing Dendra2-PH(PLCδ) labeled with the same primary antibody against HA and an Alexa647-tagged secondary antibody. HA clusters at the PM were tightly spatially correlated with PIP2 at the diffraction-limited length scale and also at the nanoscale for HA overexpressed from two different influenza strains, labeled with antibodies or fluorescent proteins, in two cell types (Fig. 1; Fig. S1). The Pearson coefficient was also significantly above zero for all length scales tested (Fig. 1 K). We observed that not all clusters showed colocalization and that even within a given cluster of HA or PIP2, there could be subregions with colocalization and other regions without colocalization. Although previous reports have implicated PIP2-related processes during influenza infection (19, 52, 53, 54), this is the first report, to our knowledge, of coclustering of PIP2 and HA in uninfected cells.

Figure 1.

Influenza hemagglutinin (HA) coclusters with PIP2 at the PM. Whole HAb2 cells were transfected with PLCδ-PH-CFP (green), a construct encoding the PIP2 binding and labeling the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. Cells were fixed and immunostained with an HA-specific monoclonal primary antibody and a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa Fluor 647. Confocal projections of all axial slices are shown in (A) and (E), and apical membranes of boxed region in (A) and (E) are shown magnified in (B)–(D) and (F)–(H). Scale bars, 10 μm. (I) A two-color super-resolution (FPALM) image of HA and Dendra2-PH in the ventral surface of fixed HAb2 cells labeled using a primary antibody against HA (Japan) followed by an Alexa647-tagged secondary is shown. Intensity is proportional to the number of localizations within each 20 × 20 nm2 pixel. Note the areas of colocalization of HA and Dendra2-PH (blue filled carats) and also some areas that do not have colocalization. (J) A two-color FPALM image (Gaussian spot plotted for each localization) of the ventral surface of fixed NIH-3T3 cells expressing Dendra2-HA (X31) and PAmKate-PH in a TIRF illumination geometry is shown. Note the areas of colocalization (blue filled carats). (K) Quantification of colocalization using bleedthrough-corrected Pearson coefficient from super-resolution microscopy data sets (images of Dendra2-HA + PAmKate-PH similar to the one shown in (J)) as a function of the size of the grid used for binning localizations is shown. Points represent the mean of 20 cells imaged in three separate biological replicates. Error bars represent standard error.

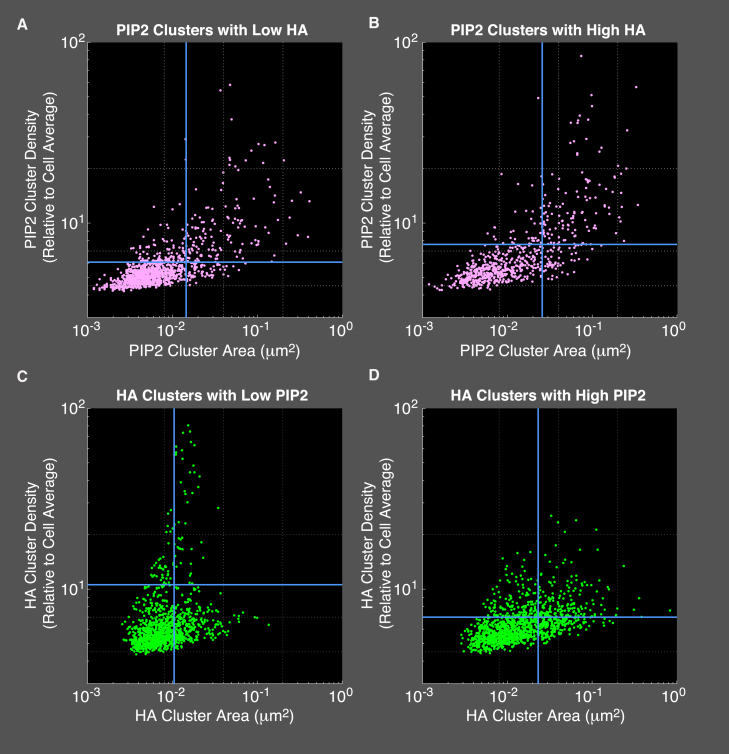

We chose to quantify cluster area and density as a measure of the size and degree of enrichment of molecules within the observed membrane patches. For HA, cluster density modulates the probability of membrane fusion and is therefore important for viral entry (13, 55, 56, 57, 58). Cluster area and density were determined for PIP2 and HA from the localized coordinates of PAmKate-PH(PLCδ) and Dendra2-HA, respectively, in fixed NIH-3T3 cells (Fig. 2; Table 1). The distribution of areas and densities is broad, spanning nearly three and two orders of magnitude in area and density, respectively. However, a region within the parameter space of area and density is enriched: most clusters tend to exist within a zone of area <0.04 μm2 and relative density <10× average, with a slight upward trend in density as a function of area. This trend suggests that the largest PIP2 clusters are also the densest. Furthermore, the results show that PIP2 is clustered even in areas with relatively low HA (Fig. 2 A; HA density less than 0.05 times the cell average). However, comparing the distribution of PIP2 cluster properties in areas with high HA (Fig. 2 B; HA density greater than five times the cell average), the mean PIP2 cluster area (A = 0.0257 ± 0.0060 μm2) and relative density (Drel = 7.6 ± 0.8) both increase significantly (p < 0.0001 using two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test) compared to their values in regions with low HA (A = 0.0145 ± 0.0020 μm2; Drel = 6.08 ± 0.60). Because of the wide range in the distribution of clusters, the SDs in area (σA = 0.0324 μm2 and σA = 0.0414 μm2 for low and high HA, respectively) and density (σD = 3.6 and σD = 6.3 for low and high HA, respectively) are also large. Despite the cluster-to-cluster variability, the area and density of PIP2 are higher on average in regions of high HA density.

Figure 2.

PIP2 cluster properties with and without influenza HA. Super-resolution microscopy was used to image Dendra2-HA and PAmKate-PH(PLCδ) simultaneously within transfected, fixed NIH-3T3 cells. Localized PAmKate-PH molecules (see Fig. 1) were analyzed to identify clusters of PIP2 (see Materials and Methods), and the properties of those clusters were quantified. (A) A scatter plot of PIP2 cluster properties (pink circles; n = 1065 clusters) yields a mean PIP2 cluster area of 0.0145 ± 0.0020 μm2 and a mean PIP2 cluster density of Drel = 6.1 ± 0.6 in regions of low HA (average of HA density within these clusters was less than 0.05 times the cell average density of HA). (B) A scatter plot of PIP2 cluster properties (n = 666 clusters) but in regions containing high HA (average of HA density of at least five times the cell average) yielded a mean PIP2 cluster area of 0.026 ± 0.006 μm2 and a mean cluster density of Drel = 7.6 ± 0.8 times the cell average. (C) A scatter plot of HA cluster properties (green circles; n = 1140 clusters) yields a mean HA cluster area of 0.0105 ± 0.0005 μm2 and a mean HA cluster relative density of Drel = 10.6 ± 5.0 times the average cell density in regions of low PIP2 (average of PIP2 density within these clusters was less than 0.05 times the cell average density of PIP2). (D) A scatter plot of HA cluster properties (green circles; n = 1233 clusters) with high local PIP2 yielded a mean HA cluster area of 0.0231 ± 0.0014 μm2 and a mean HA cluster density Drel = 7.0 ± 0.5. Data shown are the aggregate of 38 cells and five biological replicates. HA and PIP2 clusters were defined as a local relative density Drel ≥ 4 times the cell average and required ≥10 localizations for further analysis. Mean relative density and area are shown for each condition (blue lines). Uncertainties reported are standard error of the mean of the five independent biological replicates. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

PIP2 and HA Cluster Properties Observed by Super-Resolution Microscopy

| Cluster Type (Condition) | Number of Clusters | Relative Cluster Density (Drel) | Mean Cluster Area (μm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIP2 clusters (low HA) | 1065 | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 0.0145 ± 0.0020 |

| PIP2 clusters (high HA) | 666 | 7.6 ± 0.8a | 0.0257 ± 0.0060a |

| HA clusters (low PIP2) | 1140 | 10.6 ± 5.0 | 0.0105 ± 0.0005 |

| HA clusters (high PIP2) | 1233 | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 0.0231 ± 0.0014a |

Significant difference (p < 0.05) comparing low versus high HA (for PIP2 clusters) or comparing low versus high PIP2 (for HA clusters).

Quantification of HA cluster properties is shown in Fig. 2, C and D. First, to test consistency with previously reported work (9), we analyzed the HA data reported here without consideration of local PIP2 levels and with the requirement of at least 200 localizations per cluster (used previously to focus analysis on larger clusters) and obtained a mean cluster area of A = 0.150 ± 0.016 μm2, in excellent agreement with previous work. Next, we compared HA properties as a function of the local level of PIP2 averaged over each HA cluster, and we broadened our quantification to HA clusters of 10 localizations or more (Fig. 2, C and D). Again, the distribution of areas and densities is broad but distinct from the pattern for PIP2, with a pronounced population of highly dense, small clusters in regions with low PIP2 (Fig. 2 C). This population disappears in regions with high PIP2 (Fig. 2 D), and the mean HA area increases from 0.0105 ± 0.0005 to 0.0231 ± 0.0014 μm2. A Mann-Whitney U-test (two-tailed) showed significant difference (p = 0.008) between the mean areas of HA clusters with low versus high PIP2; HA clusters are significantly larger in areas of high PIP2 density. The mean HA densities also appear to change, but because of the high variation in HA density, the differences were not significant (p = 0.06) using the Mann-Whitney U-test test, although they were significant using a one-tailed Wilcoxon test (p = 0.03). In summary, the HA cluster area is observed to increase significantly in membrane regions containing high PIP2 density. Taken together with the observation that PIP2 clusters depend on local HA density, these results suggest an interdependence of PIP2 and HA cluster properties on one another.

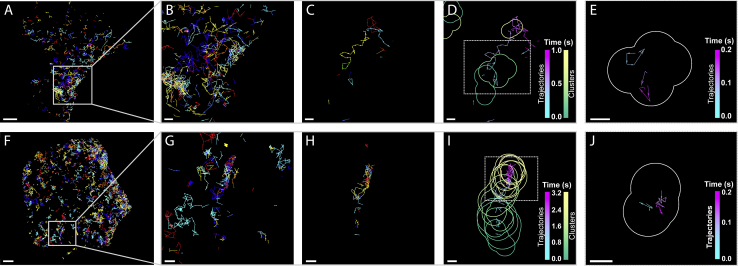

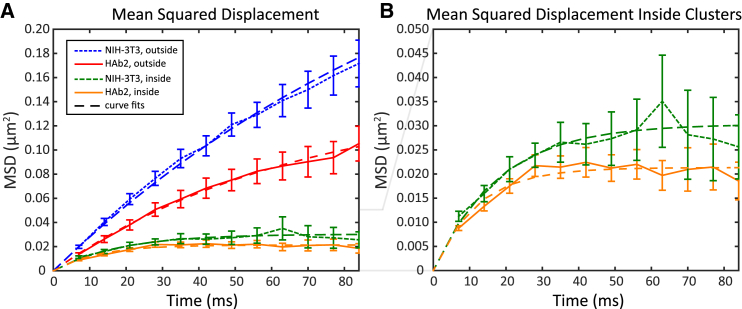

Molecular trajectories of fluorescently labeled PIP2 in living cells

We hypothesized that this striking and consistent HA-PIP2 spatial overlap was due to changes in the dynamics of clustered PIP2 and that once within clusters, PIP2 confinement would increase with HA expression. The fluorescent analog of PIP2 (C16-BODIPY-TMR-PIP2; GloPIP) (21) was used to label living NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cells using the carrier protein histone H1 for delivery across the PM. Live cells were then imaged on their basal surfaces with FPALM at 37°C and 5% CO2 with relatively low laser intensities (561 nm laser at <0.3 kW/cm2) in a TIRF geometry. GloPIP has been shown previously to be bound selectively by appropriate PH domains that are known to bind PIP2 (21). Images were acquired every 7 ms, allowing trajectories of many thousands of individual PIP2 molecules per cell to be determined, with mean localization precisions of 20–30 nm.

The appearance of PIP2 clusters is apparent on the 200 ms timescale (Fig. 3). By rendering the entire data set (10,000 frames) as one image, the movement of groups of PIP2 molecules throughout the cell could be visualized; however, the dynamics of structures was better visualized using subsets of the full data set. Trajectories were plotted with 7 ms time steps (see above), but we hypothesized that the confinement of PIP2 was dependent on their inclusion in clusters, which were not readily identifiable in individual 7 ms frames because of the need to sample a given cluster multiple times to discern its shape. To quantify the clustering of PIP2, a timescale for the dynamics was established using the fastest-moving group of PIP2 molecules from all data sets, which then was used to determine the smallest number of frames needed to comprise a rendered image of the clusters (given the temporal resolution of the movement of the cluster itself; Fig. S2). We checked the validity of this choice of timescale by running SLCA as described previously (9) on a range of time increments (50 ms–5 s). We found that at longer time increments (>500 ms), mobile clusters appeared to become elongated because of the motion of the cluster. On short timescales (50–100 ms), even the most mobile clusters appeared stationary. We therefore chose a time increment of 200 ms, which provided enough data for detection of clusters and provided trajectory overlays while limiting artifactual cluster elongation due to cluster movement.

Figure 3.

Confinement of PIP2 in clusters is increased in HAb2 cells. Single-molecule trajectories, recorded in 7 ms exposure times over a 70 s time period, are plotted with a random color assignment for representative NIH-3T3 (A) and HAb2 (F) cells. The regions in the gray boxes are enlarged (B and G) for each cell. For display, trajectories spanning a 3 s period (429 frames) are shown with random color assignments (C and H). Clusters identified with SLCA (in temporal subsets of 200 ms throughout the 3 s period) are overlaid onto the trajectories, with trajectory and cluster color assignments plotted as a function of time (D and I). A 200 ms time increment isolated from each overlay (E and J) shows cluster outlines in white and trajectories plotted according to time. Scale bars, 1 μm in (A) and (F) and 200 nm for all other panels. Rendered images were increased in brightness to improve visibility. To see this figure in color, go online.

Using this configuration, data sets were then rendered in ∼200 ms subsets (∼28 consecutive frames comprising each render). Data were then segregated (localizations not included in trajectories were used to render the cluster, whereas localizations contained in trajectories were not) to ensure the independence of trajectories and those molecules used for cluster analyses. Trajectories were identified as previously described (9), except that the initial localization in each trajectory was not considered for any of the following analysis and instead was compiled along with all molecules that were not identified as being within trajectories (i.e., those that fluoresced for one frame only) and used in identifying clusters within blocks of ∼200 ms. Highly mobile clusters were observed moving at a rate as high as ∼0.7 μm/s, but on average, clusters typically moved <0.10 μm/s (Fig. S2).

We then identified the timescale on which PIP2 clusters were reorganizing. Clusters were identified using SLCA (9) (see Materials and Methods), and trajectory data were overlaid onto these cluster maps (Fig. 3), yielding ∼350 maps of combined cluster/trajectory data per cell. This allowed the comparison of PIP2 molecules that were moving within clusters versus those that were not associated with clusters. Through comparison of NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cells, we assessed the effects of HA expression on PIP2 mobility (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Confinement of PIP2 is altered in HAb2 cells. (A) The mean-squared displacement (MSD) of all trajectories inside clusters was calculated for each cell type (HAb2: n = 22 cells, NIH-3T3: n = 25 cells; three replicates of each cell type). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. The data were fitted to MSD = MSDp × (1 − e−t/τ), where MSDp represents the plateau value of the curve and τ represents the time constant. MSDp = 0.030 ± 0.002 μm2 (NIH-3T3) and 0.0213 ± 0.0013 μm2 (HAb2), with error equal to the 95% confidence interval. The values approximately correspond to a mean radius of mobility of individual PIP2 molecules as 0.098 ± 0.005 μm for NIH-3T3 cells and 0.082 ± 0.004 μm for HAb2 cells. Diffusion rate inside clusters: (HAb2) 0.61 ± 0.04 μm2/s and (NIH-3T3) 0.61 ± 0.22 μm2/s. Diffusion rate outside clusters: (HAb2) 1.76 ± 0.09 μm2/s and (NIH-3T3) 2.70 ± 0.37 μm2/s. (B) An enlarged view of the MSD for trajectories inside clusters in NIH-3T3 cells (green line) and HAb2 cells (yellow line) is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Within each NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cell, mean-squared displacement (MSD) analysis showed an increased confinement of PIP2 molecules within PIP2 clusters (Fig. 4). When HA was present, PIP2 diffusion was more confined than when HA was not present; there was a smaller average zone of mobility within HAb2 cells (0.082 ± 0.004 μm) than in NIH-3T3 cells (0.098 ± 0.005 μm). A clustered distribution of PIP2 was also observed in super-resolution images of Dendra2-PH transfected into NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cells, and these results also support an increased density of PIP2 in clusters in cells expressing HA (Fig. S3).

Comparison of PIP2 cluster properties with previously published work

Curiously, the previously reported PIP2 cluster sizes in PC12 membrane sheets (diameters average ∼0.073 ± 0.042 μm) (33) and in whole PC12 cells (diameters average ∼0.064 ± 0.027 μm) (34) have larger variance than those in our data and correspond to smaller clusters than our mean size (PIP2 cluster diameter ∼135 ± 9 and 182 ± 21 nm in regions with low and high HA, respectively, calculated from the mean cluster area assuming a circular shape). Although cell-type variability may explain some of these differences, it is also worthwhile to consider the differences in physical basis of each measurement, the differences in effective resolution of the techniques (33, 34), and in the case of localization microscopy, the differences in labeling density (59). Furthermore, we observe that many PIP2 clusters are elongated rather than round (Fig. 1), precluding the specification of a single cluster diameter and leading us to prefer the use of area as a measure of cluster size. In addition, by measuring the mobility of individual molecules, we are able to quantify somewhat shorter length- and timescales than are accessible by imaging entire clusters with stimulated emission depletion (33), revealing additional dynamic information relevant to the cluster properties visualized previously. The mixture of homogeneous and clustered distributions of PIP2 observed in INS-1 cells contained regions of relatively uniform PH distribution and patches of PH-labeled PIP2 with diameters of 383 ± 14 nm (38), which are larger than those observed by others (33, 34) and in this study (Figs. 1, 2, and S3) on NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cells. Furthermore, the results in INS-1 cells (38) were quantified using the Ripley’s K test (60, 61), which integrates particle observations within a given distance from each particular particle, averaging over all particles (11, 62, 63), rather than measuring the number of particles at a given distance (plus or minus a small interval) from each particle, averaging over all particles, as the pair correlation function does. In another study, a relatively unclustered distribution of PIP2 was observed by electron microscopy labeling PIP2 with a tandem PH construct (37). Although the majority of our analysis has been focused on the clusters of PIP2 and their properties, we do observe membrane regions with PIP2 densities that are nonzero but below the average value for the cell (Fig. 2, A and B), which could correspond to levels that would be classified as unclustered by other criteria. Again, differences in cell type and labeling method (single PH versus tandem PH) could be expected to yield different results. However, in our cell types and using both directly labeled PIP2 as well as PH-domain labeling, we generally observe a clustered distribution of PIP2 (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and S3).

The elongated shape of PIP2 clusters in some cases (Fig. 1) is consistent with the (partial) colocalization of PIP2 with HA clusters, which have previously been shown to have elongated shapes (9, 10, 11). Although there are many biological explanations for such an elongated shape (localization to filopodia, microvilli, or other curved membranes), our previous work has shown that HA clusters tend be elongated when colocalized with actin-rich membrane regions (ARMRs) (9). Because of the known association of PIP2 with actin and actin-binding proteins (64), we hypothesize that at least some of the elongation observed here in PIP2 clusters is due to associations with HA and ARMRs.

Successful fixation of PH domain for visualization of PIP2 distribution

Chemical fixation of membrane components is notoriously complex and sometimes only partially effective (65). Therefore, we tested the ability of the Dendra2-PLCδ-PH construct to be fixed in cells. After plating and transfection of HAb2 fibroblasts followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (see Materials and Methods), we imaged the fixed sample using FPALM and carried out trajectory analysis of molecules localized for more than one frame. The averages of the SDs of the x and y coordinates per trajectory with two or more steps (∼140,000 trajectories over 13 cells) were 32.74 ± 0.08 and 33.09 ± 0.08 nm, respectively, which were comparable to the average x and y localization precisions of the fitted molecules. This result suggests that the Dendra2-PLCδ-PH molecules, on average, did not show detectable movement (within the localization uncertainty of our methods) and were adequately fixed by paraformaldehyde under the conditions we used. To test whether the HA-dependent trends in PIP2 clustering were similar using the PH domain to label PIP2 rather than GloPIP, we performed super-resolution microscopy on HAb2 and NIH-3T3 cells expressing Dendra2-PH and quantified the spatial distribution of Dendra2-PH (Fig. S3). Consistent with our results for GloPIP, the distribution of PIP2 densities visualized using Dendra2-PH shows an enhancement in PIP2 density and clustering in cells overexpressing HA in comparison to cells not expressing HA.

Analysis of live-cell dynamics versus confinement models

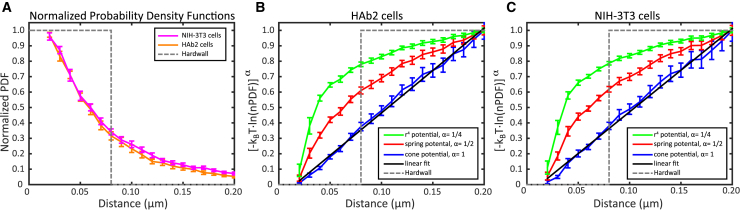

To characterize the nature of PIP2 confinement when in clusters, we fitted live-cell GloPIP trajectory data to various confinement models (Fig. 5). As established in Jin et al. (47), we examined the nPDF (see Materials and Methods), calculated using Eq. 4, for PIP2 localizations as a function of distance from the cluster center. The hardwall potential allows free diffusion within the cluster, whereas the wall confines trajectories and restricts their exit (akin to the actin fence (1)). The spring potential can describe a tether between an anchor and the molecule diffusing within the membrane and also predict a specific functional form for the nPDF (see Materials and Methods). In the cone potential, the attraction can be represented as an inward radial force of uniform magnitude, often attributed to viscoelastic forces (47, 66), whereas in the spring potential, the force of attraction is also radial but increases in magnitude proportional to the radial distance. The r4 model represents a strongly distance-dependent potential in which a radially inward force pulls molecules gently at small distances but much more strongly at large distances.

Figure 5.

PIP2 molecules are confined with motion characteristic of a “cone” potential. (A) The nPDFs were calculated for the PIP2 trajectories in NIH-3T3 (purple curve) and HAb2 (orange curve) cells as a function of r, the distance from the cluster center. The expected nPDF curve for the hardwall model with a cluster radius of 0.08 μm is overlaid (gray dashed line). (B and C) The linearized nPDF using Eq. 4 (see Materials and Methods) for the cone (blue curve), spring (red curve), and r4 (green curve) potentials are shown for the HAb2 (B) and NIH-3T3 (C) cells. The expected distribution for the hardwall potential (gray dashed lines) with a cluster radius of 0.08 μm is shown (B and C). For both HAb2 and NIH-3T3 cells, the transformed cone potential (blue curve) more closely follows a linear relationship (black dashed line) with the distance from the cluster center, r, than either the spring or r4 potentials. For the cone potential, the slope of the linear fit represents the force acting on the PIP2 molecules: 0.079 ± 0.002 pN (HAb2) and 0.071 ± 0.003 pN (NIH-3T3 cells), respectively (errors are SD from the fit). A Mann-Whitney U-test yielded p = 0.046 for the comparison of the forces (HAb2 versus NIH-3T3). Within (A)–(C), error bars are represented by the SD of the mean (n = 20 and 21 HAb2 and NIH-3T3 cells, respectively, combining data from three replicates). To see this figure in color, go online.

In our data sets, PIP2 molecules in both NIH-3T3 and HAb2 cells display confinement that much more closely approximates the cone potential than any of the other potentials (see Fig. 5). Put simply, PIP2 molecules move as if they are attracted to the center of the cluster by a constant force of ∼0.08 pN (Fig. 5 legend). Mobile PIP2 molecules diffusing within a radially symmetrical potential will have a lower probability of moving to regions of higher potential and will concentrate close to the center of the cluster. Accordingly, starting from such a central position, their tendency to take two steps in the same direction (and therefore increase their distance from the center of the cluster) will be less likely than a first step in a given direction followed by a second step in a different (i.e., lateral or inward) direction. Furthermore, as observed previously for HA, motion of molecules within a crowded membrane environment associated with cortical actin leads to reduced mobility and a tendency toward reversals in direction (9). This force could also be explained by previously observed electric fields (∼105 V/m) (67) acting upon partially screened charges within the PIP2 headgroup (21).

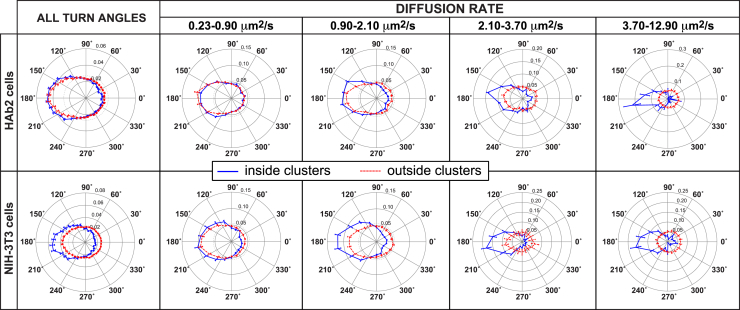

To test this prediction, turn angles (the angle between the direction of a given step and the previous one) from trajectories of PIP2 molecules were assessed and categorized (Fig. 6). Within both cell types, clustered PIP2 molecules, regardless of speed, had turn angle histograms with significant biases toward 180°, showing similarity to HA dynamics reported previously (9). Molecules that took a step in one direction were more likely to take their second step in the opposite direction (Fig. 6; Table S1) rather than continuing in the same direction. Such biases in the turn angle histogram suggest molecular confinement (Fig. S4). Although the forces acting on PIP2 molecules are similar in form when comparing the cell types (Figs. 3, 4, 5, and 6), within HAb2 cells, those fastest molecules (3.7–12.9 μm2/s) were more highly confined (Fig. 6; Table S2), in agreement with the smaller zone of confinement we observed with MSD analysis (Fig. 4).

Figure 6.

PIP2 turn angle dependence on HA expression and PIP2 clustering. Trajectories were categorized according to diffusion coefficient (see figure for key) and normalized, and fractions of turn angles were plotted. The diffusion coefficients are binned according to the distance moved. The smallest bin, D = 0–0.23 μm2/s (equivalent to a 0–40 nm step per frame), was disregarded because these displacements were approaching the limit of the localization precision (∼25 nm). The bins shown include 0.23–0.9 μm2/s (40–80 nm steps); 0.9–2.1 μm2/s (80–120 nm steps); 2.1–3.7 μm2/s (120–160 nm steps), and 3.7–12.9 μm2/s (160–300 nm steps). The final bin represents all trajectories faster than 3.7 μm2/s; steps within trajectories must be less than 300 nm for them to be counted as part of that trajectory (see Materials and Methods). Only those trajectories that were entirely inside or entirely outside clusters were counted (trajectories crossing cluster borders were not used in these analyses). Figures show an average of n = 15 cells combined from three replicates. Error bars are standard error of the mean. To see this figure in color, go online.

Outside of clusters, in NIH-3T3 cells, the two fastest classes of trajectories (2.1–12.9 μm2/s) had turn angles approximating a circular distribution (Fig. 6), consistent with freely diffusing lipids. These fast molecules apparently were not consistently bound to any underlying structure of lower mobility. Membrane-bound PIP2 can bind to a number of molecular species in the PM and in the cytosol. Molecules from slower classes (0.23–2.1 μm2/s) had turn angles significantly different from circular distributions; these lipids may represent PIP2 associated with isolated structures (or individual proteins and lipids) adjacent to or in the PM. This speed-based dichotomy was lost in HAb2 cells because all PIP2 molecules, regardless of mobility (within the range of 0.23–12.9 μm2/s), had significant biases toward 180° (Tables S1 and S2). Thus, HA expression restricted diffusion of all PIP2 populations observed.

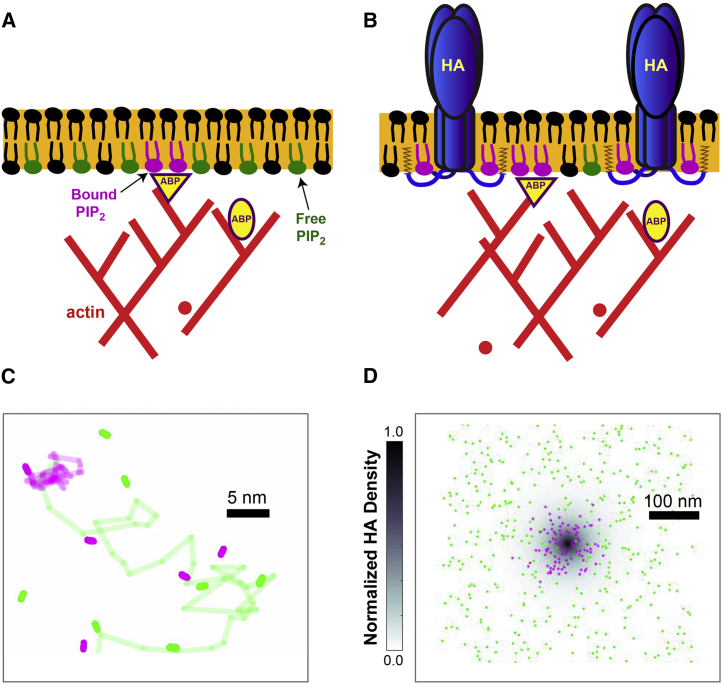

Because of the dependence of PIP2 clustering and dynamics on the presence of HA (and potentially indirectly through ARMRs known to colocalize with HA), we propose that PIP2 may bind transiently to a protein (or complex of proteins) that acts to restrict lateral mobility and that itself has a spatial gradient (Fig. 7). PIP2 molecules would be more likely to reverse steps while confined within a cluster (Fig. S4), and the net movement of PIP2 molecules would be on average toward the highest concentration of binding sites, at the center of the cluster. This pattern of movement is consistent with the observed propensity of PIP2 for turn angles around 180° when clustered (see Fig. 6) and the close agreement of PIP2 movement with the “cone” potential (see Fig. 5).

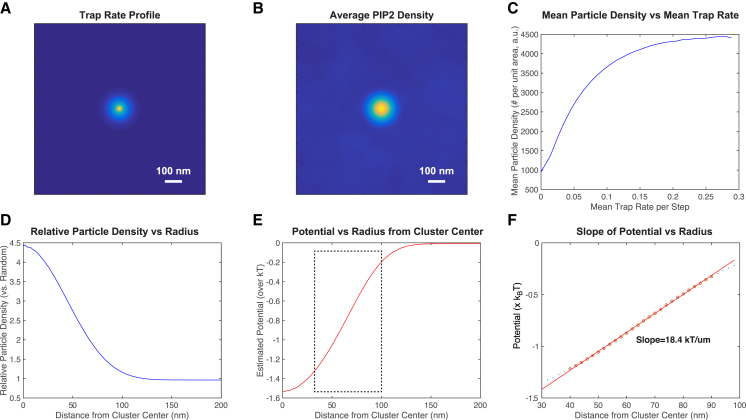

Figure 7.

Simulation of interactions between HA and PIP2. PIP2 molecules were simulated to diffuse in a two-dimensional membrane (periodic boundary conditions) in the presence of HA clusters with the experimentally determined spatial distribution (the radial pair correlation function) measured by FPALM (from Gudheti et al. (9)). (A) HAs were considered to be traps for PIP2 with a rate of trapping a PIP2 per time step proportional to the density of HA. (B) The spatial dependence of trapping led to a gradient in density of PIP2 as a function of radius from the center of the HA cluster and (C) as a function of the local concentration of HA. (D) The gradient in density of PIP2 was analyzed in the form of Eq. 1 to measure an effective potential (E). Note the spatial dependence of the potential is approximately linear for the range of ∼30–100 nm, effectively reproducing the experimentally observed cone potential, except at the shortest length scales (<30 nm), at which experimental localization precision precludes measurement. (F) The fit of simulated potential over the experimentally relevant range of distances yields a slope of 18.4 kBT/μm, consistent with the experimentally measured value of 18.9 ± 1.1 kBT/μm (the error given is the 95% confidence interval of the fitted slope). To see this figure in color, go online.

To test whether the interpretation of PIP2 dynamics is consistent with such a binding gradient model, we performed Monte Carlo simulations of PIP2 diffusion in the presence of mobile binding sites with the same properties and spatial distribution as HA, using experimental data for PIP2 and HA determined here or published previously (9, 68, 69) and neglecting the intracellular concentration of Mg2+ (see also Materials and Methods). Results from these simulations reproduce the measured spatial distribution of PIP2 (Fig. 7) and the form and slope of the effective potential measured for PIP2 (Fig. 7), which is equal to the experimentally determined force (Fig. 5).

Comparison with predictions of gradient model

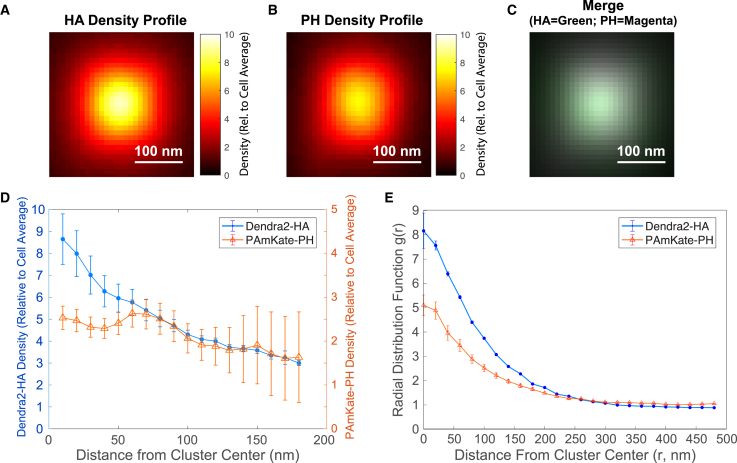

To test whether our observations are consistent with the gradient in PIP2 as a function of HA, we analyzed the super-resolution microscopy data sets for HA and PIP2 (Fig. 1) and averaged the HA and PIP2 density as a function of distance from the center of the cluster (Fig. 8), determined by two methods: 1) the erosion method (Fig. 8 D) determines density starting from the edge of the cluster, progressively eroding 10-nm-thick (potentially noncircular) shells from the edge and calculating the average density within each shell. This method tends to average together data from different clusters at the same distance from the outer edge of the cluster; and 2) the radial method: in contrast, the radial distance method starts at the cluster center and measures density within circular rings as a function of distance, averaging data from different clusters at the same distance measured from the center of the cluster. The density derived from these two methods has a slightly different form (Fig. 8). The erosion-based method will represent (for the smallest values of distance) the average of density in only the largest clusters, namely those that were sufficiently large to contain HA at larger distances (>100 nm) from the edge. The radial-based method will align the centers of both large and small clusters, yielding an average cluster as a function of distance from the cluster center but neglecting the distance from the cluster edge (beyond which the HA density drops below the threshold for a cluster). Thus, the differences in density observed could be explained because of these differences in how clusters are averaged. However, the trend of decreasing density of both HA and PIP2 in parallel as a function of distance from the cluster center is consistent for both methods and consistent with the prediction of the gradient model that HA and PIP2 should parallel each other in radial density (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the distance at which the density of HA and PIP2 drop below 4× and 2× the average density, namely ∼110 nm (erosion) and 120 nm (radial) for PIP2 and ∼120 nm (erosion) and 90 nm (radial) for HA, are similar to the sizes of PIP2 clusters determined from single-molecule mobility measurements of GloPIP (Fig. 3). Thus, predictions of the gradient model are consistent with observations using multiple methods of labeling HA and PIP2 in multiple cell types.

Figure 8.

Measured spatial dependence of PAmKate-PH density parallels the density of HA in the vicinity of HA clusters. Analysis of two-color super-resolution microscopy of Dendra2-HA and PAmKate-PH(PLCδ) was performed on HA clusters identified by areas with a local HA density at least four times the average for the cell. (A–C) Average density profiles of large HA clusters identified (those with at least 20 localizations) are shown. Each cluster (with density measured relative to the average for that cell) was aligned to place its center of mass at the coordinate origin. Then, the pixel-based sum of all clusters was taken, and the result was divided by the number of clusters averaged. Note the close similarity in the spatial dependence of (A) the Dendra2-HA density and (B) the PAmKate-PH density. (C) shows a merge of the profiles shown in (A) and (D), with HA colored green and PH colored magenta. (D) For each HA cluster, the density of HA and PIP2 were determined within annular shells of uniform 10 nm thickness progressing from the outer edge of the cluster and moving inward until the center of the cluster was reached. The density profile was then averaged for all HA clusters imaged (n = 4010 clusters with at least 10 localizations each from a total of 15 cells from two biological replicates). (E) For each HA cluster, the radial distribution function g(r) was calculated for HA and PIP2 localizations as a function of r, the radial distance from the center of mass of the cluster. As in (D), the value of g(r) is normalized to be 1 when equal to the average density for each cell, then averaged over all clusters (n = 1969 clusters of at least 20 localizations each from a total of 15 cells from two biological replicates). Note the similar decaying trend for both HA and PIP2 as a function of distance. Error bars are the standard error of the mean. To see this figure in color, go online.

Comparison of clustering and dynamics with published models of membrane organization

The spatial distribution simulations are inconsistent with the predictions of other potentials based on membrane models discussed within this manuscript (Fig. S5). Here, we discuss those differences in further detail.

Raft model

Although there is already considerable evidence refuting the raft concept for lipid domain formation (9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17, 70, 71, 72), it is worth pointing out that we here show a canonical example of a raft protein (HA), together with a functionally important lipid (PIP2), imaged and quantified by super-resolution microscopy. HA and PIP2 both form PM clusters and are often colocalized (Fig. 1). Although there are many possible predictions for the shape and density profiles of the multiple published definitions of a raft (2, 69, 73, 74), we thought it worthwhile to consider a circular domain with uniform (attractive) potential within, which leads to the prediction of a uniform density within the domain. In addition to the previous observations that HA does not form circular domains (9), our observations for both HA and PIP2 show a decrease in density as a function of distance from the cluster center, which was strikingly inconsistent with the prediction of a domain with uniform density (Fig. S5). The finding that PIP2 is uniformly distributed (38) and the prediction that PIP2 forms PM domains that are too small and transient to be observed on timescales of seconds (75) do not appear to hold for PIP2 in the cell types and at the levels of sampling we have observed.

Fence model

Based on our observations, the concept of a fence that confines diffusion of lipid and protein in the PM (76, 77, 78, 79) is still viable, but its original form would need to be modified to be consistent with our observations for HA and PIP2. For example, considering an actin-based fence (80) in cells expressing HA, the zones serving as the fence in the PM would need to contain mobile HA trimers, which we observe to colocalize with actin (9). These zones could still act to confine lipid diffusion, but they would not strictly act as a wall for lipids because we observe PIP2 is able to occupy zones together with HA while also being confined within clusters (Figs. 1, 3, 4, 5, and 8). Finally, the potential within the fence would need to be spatially variable—unlike a simple open area with constant potential—to yield particle densities that are spatially variable, and the potential would also need to yield a molecular mobility that is spatially variable, as we observe for HA (9) and PIP2 (Figs. 4 and 6). Our observation that HA expression can alter actin organization (Fig. S6) further complicates the picture.

Tether model

Our observations for HA and PIP2 show a potential that varies linearly with distance from the cluster center, not quadratically as would be predicted for a spring-like tether (47). Some more complex combination of tethers with spatially varying spring constants organized around the centers of HA/PIP2 clusters could perhaps be invoked to explain the results, but the details of such a scheme are not currently obvious.

Models of spatially segregated PIP2-modulated PM function

Several recently published models for PIP2 recruitment, synthesis, and modulation of protein activities (81) could help explain the diversity of PIP2 and HA cluster properties and coclustering we observe. For example, pre-existing PIP2 clusters (“platforms”) or unclustered, laterally mobile PIP2s from a “megapool” (81) could be recruited and modulated by effector proteins (in this example, HA clusters) in a time-dependent manner, leading to local modulation of available PIP2 density (21, 27), modulation of signaling pathways, and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (26). In such a case, one would expect that PIP2 clusters interacting with HA would change their area, density, and mobility immediately, whereas others would behave distinctly until encountering an HA cluster or until the changes in the overall state of the cell had a modulatory effect on the PIP2 clustering, potentially through signaling pathways, actin, or actin-binding proteins. Furthermore, a megapool of unclustered PIP2 (81) would be expected to show examples of freely diffusing PIP2 molecules outside of clusters induced by effectors. Time-dependent spatial visualization of phosphoinositide kinases together with PIP2 and effectors could be quite helpful for testing the possibility of “selfish PIP2 synthesis” (81). Distinction between these possibilities could reveal multiple populations of HA and PIP2 (both clustered and unclustered); explain the large variability in cluster properties and the spatial dependence of HA-PIP2 colocalization; and lend support for time-dependent membrane models coupling clustering, confinement, signaling, and cell function. Furthermore, because HA is just one example of a membrane protein that associates with PIP2, any subpopulations discovered could be generalized to describe other (cellular) membrane proteins and functions.

Mechanisms of HA-PIP2 interaction

Using both confocal and super-resolution microscopy, we show here that 1) PIP2 and HA are closely associated at the PM (Figs. 1 and 8) and 2) PIP2 clustering and dynamics are modulated by spatial gradients in potential that depend on HA (Figs. 5 and 7). The question is, how are these spatial gradients maintained? Clearly, the actin cytoskeleton plays a major role in the clustering of HA (9), yet the short (10–11 amino acids) CT of HA (20) does not contain a known actin-binding site or PH domain. However, it does contain at least two highly conserved, positively charged amino acids (20) and three acylation sites per monomer (nine per trimer) (20, 82), which could potentially interact with PIP2. Furthermore, HA is known to colocalize with a variety of actin-binding proteins (9), and HA can nucleate new actin filaments via PIP2 activation of N-WASP to increase transport from the Golgi to the PM (19). Alternatively, a nonspecific interaction between HA, PIP2, and a third membrane component could result in their colocalization and mutual interdependence. Thus, there are many potential mechanisms by which HA could interact with PIP2, either directly or indirectly (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Model of the role of HA in PIP2 clustering and dynamics. Spatial gradients in molecular mobility created by transient interactions (direct or indirect) of PIP2 with HA produce a clustered distribution of PIP2 and HA at the nanoscale. (A) Within the PM (orange), PIP2 molecules diffuse freely (green lipids) or with transient binding (magenta lipids) to membrane-associated actin-binding proteins (yellow triangle), leading to a small fraction of PIP2s diffusing with confinement. (B) HA (blue trimers) targets actin-associated membrane regions (ARMRs; Gudheti et al.(9)) and interacts with PIP2 directly or indirectly, leading to increased confinement of PIP2 diffusion and coclustering of HA and PIP2. (C and D) A top-down view of simulated PIP2 trajectories while moving freely (green) or interacting with HA (magenta) is shown. (C) The spatial gradient in lateral diffusion rates serves to bias individual PIP2 trajectories and (D) leads to a clustered distribution together with HA (dark gray zone, D). On a population level, this effect suffices to drive PIP2 clustering toward HA-rich regions (C and D) while both populations maintain some degree of lateral mobility. A video showing the dynamics of simulated PIP2 molecules can be found at https://drive.google.com/open?id=1FZi03muIGvsqLkuoAPk8HTZ37MSNFAG7.

HA and actin seem to have a two-way relationship. For example, HA expression results in an increase in actin clustering at the PM (Fig. S6), indicating feedback between membrane protein clusters and adjacent actin structures (9); previous work has shown that HA expression and/or influenza infection can modulate actin-associated intracellular signaling pathways (40, 54, 83). How does PIP2 fit in to the HA-actin relationship? In other membrane-actin coupled systems, critical ligand concentrations can drive the clustering of membrane proteins and lipids, in turn enhancing clustering and signaling of actin-nucleating N-WASP, and the local formation of actin structures, which in turn alter clustering and mobility of membrane proteins (84) and lipids. In this model, we incorporate our previous observations of ARMRs adjacent to HA clusters, considering them to provide a relatively stable framework (on timescales of tens of seconds) that interacts with the membrane, mediates HA clustering, and modulates its mobility (9) (Fig. 9). Because of the known interactions between PIP2, actin, and actin-binding proteins (64), the areas of PIP2 clustering, reduced PIP2 mobility, and confinement are very likely a result of ARMRs, at least in part.

Our observations also show that 1) PIP2 clustering is significantly altered in the presence of HA, 2) HA can modulate the mobility of PIP2, 3) the measured spatial profile of HA clusters predicts the behavior of PIP2, and 4) the measured distributions of HA and PIP2 in clusters parallel each other on average. Furthermore, the binding of PIP2 to HA could locally sequester PIP2 as proposed for other membrane proteins with multiple basic amino acids (23). There is a hint of evidence in support of HA sequestration of PIP2 in Fig. 8 D, which shows an increased binding of PAmKate-PH near HA clusters, but that does not continue to increase (on average) at the very center of the HA cluster (Fig. 8 D). The actin-binding protein cofilin can bind PIP2 (64). If the HA sequestration of PIP2 and the cofilin binding of PIP2 are mutually exclusive, then HA sequestration of PIP2 would explain the zones of cofilin exclusion previously observed near HA clusters (9), leading to zones where cofilin is less likely to be bound to the PM and potentially modulating the local actin environment of or near zones of viral assembly or budding. Further experiments are certainly needed to explore and test this hypothesis.

The finding of PIP2 colocalization with HA clusters on cell surfaces indicates that the budding virus, with a membrane enriched in HA at high density, should also contain PIP2. PIP2 may also play a role in viral entry, either in the priming or the fusion steps within the endosome, through control of ARMRs, which can mediate the density of HA clusters. The finding that a variety of Ras, Rab, Arf, and Rho-family membrane-associated proteins with polybasic residues and acylation sites are dependent on phosphoinositides (22) suggests a precedent for the association of HA with PIP2 because the CT of HA typically contains two positive amino acids and at least three acylation sites (20, 82). The recent finding that PIP2 clustering can be induced and modulated by multivalent cations (such as Ca2+ and Mg2+) (85) and the known modulation of intracellular Ca2+ during influenza infection (54) suggest it could be fruitful to investigate the role of Ca2+ signaling in HA and PIP2 coclustering. The myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) protein also shows Ca2+ dependent association with acidic PM lipids such as PIP2 through positively charged amino acids close to the inner leaflet (21). The possibility that membrane-proximal cytosolic Ca2+ (or Mg2+) levels could differ from cell to cell and within a given cell because of modulation of signaling pathways could help explain the wide variety of HA and PIP2 clustering observed while offering a readily visualized indicator of changes in those pathways.

Super-resolution microscopy has revealed that the spatial distribution of PIP2 is colocalized with and modulated by energy potentials coupled to the membrane protein HA. The observed potentials confine the diffusion of individual PIP2 molecules and encourage their clustering. The dynamics of PIP2 in the PM also reflect this HA-dependent confinement, yield similar turn angle histograms as for HA, and show that the measured spatial distribution of HA, which is itself mobile, predicts the clustering pattern of PIP2. These results also illustrate a methodology for quantifying molecular interactions on nanometer length scales and millisecond timescales.

In contrast to other mechanisms of protein-lipid interactions such as ordering of molecules into lipid rafts (2), lipid confinement by protein fences (1), tethering of lipid motion, or buffering by fixed binding sites (24), our findings describe and explain spatial PIP2 distributions and how they change in time via a distinctly dynamic mechanism—a potential gradient due to binding sites that are themselves both mobile and clustered. This model may be useful for understanding other biomembrane clusters whose distributions display gradients in density while maintaining their mobility, a property that is often necessary for biological function.

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during this study (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and S1–S6) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The scripts used for data analysis in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

N.M.C., M.J.M., K.M., M.P., M.B.B., J.W., P.R., and S.T.H. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. M.M. and J.Z. designed experiments. J.L. performed experiments and analyzed data. H.W. performed experiments. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Holowka, Tobias Baumgart, and Pietro De Camilli for useful discussions and reagents; Satyajit Mayor, Timothy Ryan, Julie A. Gosse, C.T. Hess, Andrew Nelson, Greg Innes, Neil Comins, and R. Dean Astumian for useful discussions; and Patricia Byard for technical assistance.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants R15GM116002 and R15GM094713, by an Institutional Development Award from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103423 (M.S.M.), by Maine Technology Institute grants MTAF1106 and 2061, by the University of Maine Office of the Vice President for Research, by the Maine Economic Improvement Fund, and by the Fulbright Program (K.M.). S.T.H. and M.J.M. hold licensed patents in super-resolution microscopy.

Editor: Joseph Falke.

Footnotes

Michael J. Mlodzianoski, Matthew Parent, and Michael B. Butler contributed equally to this work.

Six figures and two tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(19)30052-9.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Kusumi A., Suzuki K.G., Fujiwara T.K. Hierarchical mesoscale domain organization of the plasma membrane. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons K., Sampaio J.L. Membrane organization and lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a004697. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viola A., Gupta N. Tether and trap: regulation of membrane-raft dynamics by actin-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:889–896. doi: 10.1038/nri2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox M.M. Pandemic influenza: overview of vaccines and antiviral drugs. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2005;78:321–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann G., Noda T., Kawaoka Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2009;459:931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedson D.S. Confronting an influenza pandemic with inexpensive generic agents: can it be done? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008;8:571–576. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70070-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampathkumar P., Maki D.G. Avian H5N1 influenza--are we inching closer to a global pandemic? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2005;80:1552–1555. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flint S.J., Enquist L.W., Skalka A.M. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2000. Principles of Virology: Molecular Biology, Pathogenesis, and Control. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudheti M.V., Curthoys N.M., Hess S.T. Actin mediates the nanoscale membrane organization of the clustered membrane protein influenza hemagglutinin. Biophys. J. 2013;104:2182–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess S.T., Gould T.J., Zimmerberg J. Dynamic clustered distribution of hemagglutinin resolved at 40 nm in living cell membranes discriminates between raft theories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17370–17375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708066104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess S.T., Kumar M., Zimmerberg J. Quantitative electron microscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy of the membrane distribution of influenza hemagglutinin. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:965–976. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda M., Leser G.P., Lamb R.A. Influenza virus hemagglutinin concentrates in lipid raft microdomains for efficient viral fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14610–14617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235620100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellens H., Bentz J., White J.M. Fusion of influenza hemagglutinin-expressing fibroblasts with glycophorin-bearing liposomes: role of hemagglutinin surface density. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9697–9707. doi: 10.1021/bi00493a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisz J.F., Klitzing H.A., Kraft M.L. Sphingolipid domains in the plasma membranes of fibroblasts are not enriched with cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:16855–16861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.473207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisz J.F., Lou K., Kraft M.L. Direct chemical evidence for sphingolipid domains in the plasma membranes of fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E613–E622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216585110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraft M.L. Plasma membrane organization and function: moving past lipid rafts. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2013;24:2765–2768. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-03-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraft M.L. Sphingolipid organization in the plasma membrane and the mechanisms that influence it. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;4:154. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson R.L., Frisz J.F., Kraft M.L. Hemagglutinin clusters in the plasma membrane are not enriched with cholesterol and sphingolipids. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1652–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerriero C.J., Weixel K.M., Weisz O.A. Phosphatidylinositol 5-kinase stimulates apical biosynthetic delivery via an Arp2/3-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:15376–15384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veit M., Serebryakova M.V., Kordyukova L.V. Palmitoylation of influenza virus proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013;41:50–55. doi: 10.1042/BST20120210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambhir A., Hangyás-Mihályné G., McLaughlin S. Electrostatic sequestration of PIP2 on phospholipid membranes by basic/aromatic regions of proteins. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2188–2207. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heo W.D., Inoue T., Meyer T. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;314:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin S., Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin S., Wang J., Murray D. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balla T. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:1019–1137. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]