Abstract

Introduction

King’s College Hospital has proudly provided a one-stop neck lump clinic since 2012. These multidisciplinary clinics allow for rapid diagnoses due to in-clinic investigations. In April 2013, ultrasound-guided core needle biopsies were introduced as an alternative/adjunct to fine-needle aspiration cytology and open biopsies for obtaining histological diagnoses. The aim of the study was to assess the impact of core needle biopsies on the diagnosis of neck lumps compared with fine-needle aspiration cytology and open biopsies between April 2015 and May 2016.

Materials and methods

Data were collected prospectively between April 2015 and May 2016 and analysed for numbers of fine-needle aspiration cytology, core needle biopsies and open biopsies performed and diagnoses made.

Results

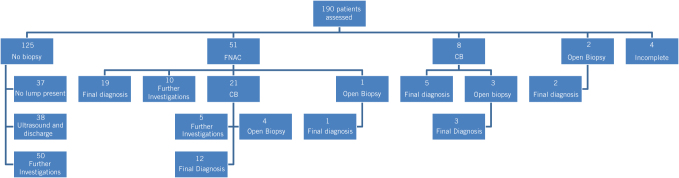

A total of 190 patients were seen on the clinic; 51 had fine-needle aspiration cytology and 19 procedures gave a diagnosis. Of the remainder of these patients, 21 went on to have a core needle biopsy and 12 biopsies gave a diagnosis. An additional eight patients only had a core needle biopsy, of which five biopsies gave a diagnosis. Of the ten patients who had an open biopsy, four had a previous fine-needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy, three only a core needle biopsy, two had neither and one had fine-needle aspiration cytology.

Conclusion

The introduction of core needle biopsies has reduced the number of open biopsies performed. With increasing acceptance of this minimally invasive technique, core needle biopsies appear to be forming the key diagnostic investigation in patients with neck lumps.

Keywords: Core needle biopsy, Fine-needle biopsy, Pathology

Introduction

Neck lumps are common findings that can present in all age groups from a range of causes including congenital, acquired, from cysts, inflammatory, infective or neoplastic disease.1 They vary in size and encompass any neck structures. Head and neck cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the UK, accounting for 3% of all new cases.2 The incidence rate shows that there are 25 new head and neck cancer cases for every 100,000 males in the UK and 11 for every 100,000 females.2 The Improving Outcomes Guidance for head and neck cancer by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has advocated the provision of one-stop diagnostic neck lump clinics for patients with suspected head and neck cancer.3 The perceived benefit of this guidance is to reach early diagnosis with immediate access to treatment in order to improve survival rates.

In response to this, King’s College Hospital, London, has provided suspected head and neck cancer patients with a one-stop neck lump clinic since 2012. It has been resourced by three rotating consultants in oral and maxillofacial surgery, one consultant in haematology, one consultant in cytopathology, two consultants in radiology and a clinical nurse specialist. These multidisciplinary clinics allow for rapid diagnoses due to in-clinic investigations. In April 2013, ultrasound-guided core needle biopsies were introduced as an alternative/adjunct to fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and open biopsies for obtaining histological diagnoses. Although FNAC has long been the most functional investigation to determine the nature of the neck lumps, the use of core needle biopsies is now becoming more common, with several studies highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each.4 Core needle biopsies are commonly used when FNAC is unable to give precise results or when it is preferable to obtain a histological examination of a lesion rather than a simple cytological examination.5

The aim of this audit was to assess the impact of core needle biopsies on the diagnosis of neck lumps compared with FNAC and open biopsies between April 2015 and May 2016. Further outcomes were measured by assessing the impact on time from referral to diagnosis and data was compared with that from previous years.

Materials and methods

Data were collected prospectively on all patients who attended the one-stop neck lump clinic at King’s College Hospital between April 2015 and May 2016. Similar data had been collected by previous researchers in a similar fashion between 2012 and 2015, which were used to compare with the results of this investigation. Held on a weekly basis, these patients would be initially assessed by a surgeon and radiologist. Investigations such as imaging, ultrasound-guided FNAC, core needle biopsies or open biopsies, or a combination of these procedures over multiple visits were carried out if deemed necessary.

Patients presenting with neck lumps without suspected lymphoma underwent an ultrasound-guided FNAC as the first-line investigation, followed by a core needle biopsy with either a 14- or 16-gauge needle if the results of the FNAC were deemed insufficient for diagnosis. If the radiologist suspected lymphoma from the patient’s scans, a core needle biopsy would be used as the first line. Patients were either given diagnoses on the day or were asked to return for follow-up once diagnoses from investigations had been reached, together with a management plan. Occasionally, FNACs and core needle biopsies were considered inadequate if the final report did not have enough viable cells to make a diagnosis and further investigations were undertaken to aid in reaching a diagnosis. The time to diagnosis was calculated in days from the referral date to the date on which the patient was informed of the diagnosis. As this was an audit of clinical practice with established guidelines, ethical approval was not required.

Results

Between April 2015 and May 2016, 190 patients were seen on the one-stop neck lump clinic. The mean age was 45.2 years (range 12–89 years); 47.9% (n = 91) were female compared with 52.1% (n = 99) male. Of these, 71.1% (n = 135) of patients presented with a neck lump. The remaining patients without neck lumps were discharged after initial consultation. The overall mean time to diagnosis was 24 days, slightly longer (mean of 27 days) for patients referred under the two-week wait referral pathway.

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the management of patients assessed in the neck lump clinic. Patients who were still undergoing investigations to reach a definitive diagnosis were listed as ‘incomplete’. Patients undergoing ‘further investigations’ were referred to a specialist for investigations beyond the scope of the neck lump clinic facilities, including imaging and haematological investigations based on the results from the FNAC.

Figure 1.

Management of patients assessed in the neck lump clinic.

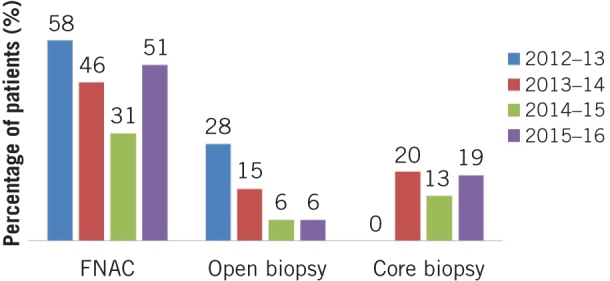

Figure 2 compares the percentage of patients with neck lumps undergoing FNAC, core needle biopsy and open biopsy every year since the formation of the one-stop neck lump clinic in 2012 until 2016. The chart shows that since the introduction of core needle biopsies in 2013, they have played a significant role in diagnosing head and neck lumps. It is worth noting that between 2012 and 2013, 80 patients were seen on the clinic, which has significantly increased to 190 patients in 2015–2016.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with neck lumps undergoing fine-needle aspiration cytology, core needle biopsies and open biopsies between 2012 and 2016.

The mean time to diagnosis was also calculated for patients who underwent FNAC, core needle biopsy and open biopsy. These data were compared with data collected in 2012–2013 and can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mean days to diagnosis for patients who underwent fine-needle aspiration cytology, core needle biopsies and open biopsies in 2012–2013 compared with 2015–2016.

The outpatient attendance rate was calculated, with 61.6% (n = 117) of patients only attending once before being discharged, while the remaining patients were seen for between two and five appointments.

In total, between April 2015 and May 2016, 20 cancers including Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 10), metastastic SSC from outside the head and neck region (n = 6) and leukaemia (n = 1) were diagnosed through various investigations. Four cancers were diagnosed from FNAC alone, nine from FNAC and core needle biopsy, three from core needle biopsy alone, one from open biopsy alone and the remaining three from other means including radiological and haematological investigations.

Discussion

The one-stop neck lump clinic has become increasingly effective over the years, providing rapid diagnoses and reducing clinic times owing to the cytopathologist who can provide immediate diagnostic information. This allows instant reassurance and early discharge of patients with benign conditions not requiring further management. It provides a rapid access service for general practitioners and other healthcare professionals.

Results from a 2012 systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of data on the role of core needle biopsies in diagnosing head and neck lumps mirror those from this study and showed that core needle biopsies provided high rates of diagnoses without major complications and achieved a higher accuracy than that of FNAC in detecting malignancy, confirming that core needle biopsies are an excellent method in the assessment of certain neck lumps.6 This supports the use of core needle biopsies in neck lump clinics as an alternative to FNAC as a first-line investigation.

The head and neck is a restricted anatomical space with many intricate and delicate structures. Any diagnostic intervention should therefore be minimally invasive to prevent any related morbidity. While open biopsies usually always provide sufficient specimens to help make a final pathological diagnosis, they create a surgical wound with compromised aesthetic outcomes and require patients to undergo general anaesthesia. On the other hand, FNAC provides minimal invasiveness, reduced costs and pathological assessment of small lesions that are not amenable to core needle biopsies; however, studies reveal that they are less accurate than core needle biopsies and hence more costly as core needle biopsies are often required.5 This is reflected here as nine lesions had FNAC which gave a failed diagnosis, which were then investigated by core needle biopsies to give a final diagnosis. Therefore, performing a core needle biopsy first may ultimately lead to a reduction in local injury and patient morbidity.

Core needle biopsies are effective in diagnosing head and neck malignancies resulting in a reduction in the number of these cases diagnosed by open biopsies. This has also been reported in neck lump clinics in other hospital units.7 They are a valuable, minimally invasive diagnostic tool that can be carried out in clinic without major complications. This study shows that Hodgkin’s lymphoma was the most common malignancy diagnosed, with cervical lymphadenopathy the usual presentation. By providing a faster diagnosis and reducing the need for open biopsies, core needle biopsies have both a clinical benefit for the patient as well as a financial benefit by reducing hospital admissions and theatre operating time.

No complications were noted in this investigation. The methods used to gain a tissue sample can give rise to complications, such as seeding tumour cells into the interstitial tissue fluid from where they are carried to the lymphatic system or into the veins draining the tissue, from where they enter the vasculature and may travel to lodge into any organ or tissue. Tissue biopsies can also increase the spread of cancer by dragging cells along the surgical incision or needle track.8 A 2016 systematic review reported seven cases of seeding from 610 articles; five were after a FNAC and two after a core needle biopsy. There was a variation between the time after the procedure and when the tumours were found (range 0 days to 3 years).9 The gauges of the core needle biopsy in these studies were between 18 and 22, smaller than those used at King’s College Hospital, hence patients should be closely monitored for potential complications. Further research from health institutions is required to establish the risks of potential seeding of tumour cells from all the three methods in head and neck cancers.

The results show that the efficiency of our service is improving, with it taking fewer days to reach a diagnosis in 2015–2016 for all investigations compared with 2012–2013. Patients are being diagnosed in a timely manner, owing to the high commitment and skills of the multidisciplinary team, with a need to maintain conformity to the Department of Health’s guidelines on waiting times.10 A 2013 review reported a reduction in days to diagnosis from referral date from 25.4 to 16.5 days after the introduction of same-day computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, which are carried out in addition to in-clinic FNAC, if necessary.11 This could be introduced at King’s College Hospital if supported by financial and operational resources.

The establishment of multidisciplinary clinics at King’s College Hospital has been critical to improvements in coordination of care for cancer patients over the past few years. Our clinical nurse specialist ensures patient continuity and coordination between hospital and community. The outcomes of this audit have made it possible to justify the implementation of core needle biopsies in the one-stop neck lump clinic by demonstrating an improvement in patient care and outcomes in the current resource framework. This innovation has allowed clinicians to meet ever-growing service needs while provide an excellent patient-focused service.

Conclusion

The implementation of the NICE guidelines has led to an improvement of cancer services to our patients. Core needle biopsies are effective in diagnosing disorders where a histological specimen is required, resulting in a reduction in the number of cases diagnosed by FNAC and open biopsy. The introduction of core needle biopsies has reduced the number of open biopsies performed from 28% in 2012–13 to 5% in 2015–16 and has led to the reduction in time from date of referral to date of diagnosis. As a result, there is both a clinical benefit for the patient and a financial benefit for the trust. With increasing acceptance of this minimally invasive technique, core needle biopsies appear to be forming the key diagnostic investigation in patients with neck lumps.

References

- 1.Rosenberg TL, Brown JJ, Jefferson GD. Evaluating the adult patient with a neck mass. Med Clin North Am 2010; (5): 1,017–1,029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Research UK Cancer Incidence Statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence?_ga=2.119202892.458733556.1540824704-669377871.1537786525#heading-One (cited October 2018).

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Improving Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancers. Cancer Service Guideline CSG6. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moschetta M, Telegrafo M, Carluccio DA et al. Comparison between fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and core needle biopsy (CNB) in the diagnosis of breast lesions. G Chir 2014; (7–8): 171–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pagni P, Spunticchia F, Barberi S et al. Use of core needle biopsy rather than fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnostic approach of breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol 2014; (2): 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novoa E, Gürtler N, Arnoux A, Kraft M. Role of ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy in the assessment of head and neck lesions: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Head Neck 2012; (10): 1,497–1,503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allin D, David S, Jacob A et al. Use of core biopsy in diagnosing cervical lymphadenopathy: a viable alternative to surgical excisional biopsy of lymph nodes? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2017; (3): 242–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healing Cancer Naturally Biopsy and surgery can spread cancer. http://www.healingcancernaturally.com/biopsies-surgery-spread-cancer.html (cited October 2018).

- 9.Shah KS, Ethunandan M. Tumour seeding after fine-needle aspiration and core biopsy of the neck and neck: a systematic review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016; (3): 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Service Cancer Reform Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randhawa PS, Lee Yi Jie J et al. One-stop triple imaging: the way forward in head and neck cancer management? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013; (Suppl): 1–4. [Google Scholar]