Abstract

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a highly aggressive malignancy that usually presents at a late stage. Common sites of metastasis include the liver, lung and adjacent lymph nodes. Cervical lymph node involvement has been reported previously but there are no documented cases of submandibular lymph node metastasis in the available literature. We describe a case of pancreatic adenocarcinoma metastasis to the left submandibular lymph node with no confirmed concurrent sites of metastasis.

Keywords: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Submandibular lymph node, Hepatopancreatobiliary surgery, Whipple’s procedure

Case history

A 77-year-old man presented with painless jaundice, dark urine and intense pruritus as well as a 6-week history of profound lethargy. His liver function tests on admission indicated alanine transaminase of 148iu/l (normal range: 2–53iu/l), total bilirubin of 46μmol/l (normal range: 0–21μmol/l) and alkaline phosphatase of 347iu/l (normal range: 30–130iu/l). His serum amylase and CA 19-9 levels were normal.

Cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography [CT] and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) demonstrated intra and extrahepatic biliary duct dilation secondary to an operable 2.5cm rounded soft tissue lesion in the head of the pancreas. As per UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence guidelines,1 the patient underwent fludeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, which confirmed activity in the pancreatic head (Fig 1 red arrow) alongside what was described as an ‘incidental’ FDG avid mass in the left submandibular region (Fig 2) and an avid lesion in the left lobe of the thyroid gland (Fig 1 blue arrow).

Figure 1.

Coronal whole body FDG PET-CT showing the primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma (red arrow) and a lesion in the left lobe of the thyroid gland (blue arrow)

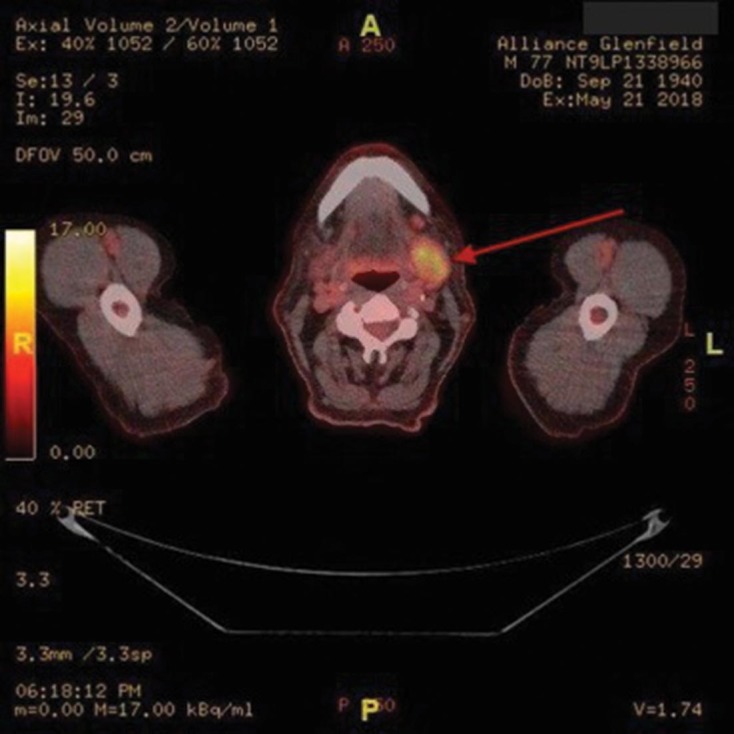

Figure 2.

Axial whole body FDG PET-CT showing a confirmed isolated metastatic site in the left submandibular lymph node (red arrow)

The case was discussed by the head and neck multidisciplinary team (MDT) and the HPB MDT. The thyroid and submandibular gland were not thought to be a priority in the context of the operable pancreatic cancer, and as part of our new fast track protocol, the patient underwent a classical Whipple’s procedure within two weeks of presentation. He made an uneventful recovery and was discharged eight days postoperatively. The final histology report confirmed a T3 N1 R0 mucinous adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas and the patient was referred for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Prior to oncology consultation, the ear, nose and throat surgeons reviewed the patient in clinic, and arranged for ultrasonography guided fine needle aspiration for the level Ib submandibular lymph node. This was reported as suspicious for metastatic disease and cytological analysis was in keeping with a diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma. However, as there was insufficient tissue, the results remained indeterminate. Subsequently, an excisional biopsy was performed. The morphological appearance of the specimen on microscopy was again determined to be that of a metastatic adenocarcinoma. Immunocytochemistry revealed it to be strongly positive for CK7 and CK5/6, with focal CA 19-9 staining. It was negative for TTF-1, IL-12 p40, CK20 and CDX2, and strongly matched the original resected specimen. As a result, a diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma was made.

Discussion

After a thorough review of the literature, we believe this is the first description of isolated submandibular lymph node metastasis from a pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The most commonly documented regions of metastasis are the liver, peritoneum, lung, bones and adrenal glands2 but there have also been several other reports of extra-abdominal, extrathoracic lymph node metastasis. Soman et al reported three patients with left supraclavicular lymph node metastasis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3 Furthermore, similar cases of lymphatic metastatic spread to the cervical region have been documented.

However, the anatomical drainage of intra-abdominal malignancy makes our case all the more perplexing as submandibular spread is highly unlikely. The anatomical mechanism of lymphatic spread of pancreatic cancer includes eventual drainage into the cisterna chyli, which drains into the thoracic duct, which in turn drains into the junction between the left subclavian and left internal jugular veins. The close proximity of the left supraclavicular lymph node to this junction explains the tendency of intra-abdominal malignancies to metastasise to this region.4 Involvement of the left submandibular lymph node, on the other hand, suggests that there is potential retrograde spread of malignant cells up the jugular trunk to the level I lymph node. This makes our case even more peculiar, especially in the context of no confirmed concurrent intra or extra-abdominal metastasis.

As an imaging modality in the staging of (pancreatic) cancer, FDG PET-CT has been shown to be the most effective means of detecting metastasis and it is superior to CT alone.5 For this reason, FDG PET-CT should be considered for cases of distant and unusual metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Had the metastasis been discovered preoperatively, the patient would have been spared an unnecessary operation. This is particularly important as pancreatoduodenectomy is associated with significant morbidity in 40–60% of patients; although our patient had a smooth postoperative course, quality of life following pancreatoduodenectomy can be considerably impaired with increased fatigue and digestive symptoms as well as reduced social functioning.6 Although these symptoms improve by six months, one could argue that in someone with a shortened life expectancy due to metastatic pancreatic cancer, this is a significant period of time.

Conclusions

This is the first documented case of isolated submandibular node metastasis secondary to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. It was detected by FDG PET-CT and subsequently confirmed by excisional biopsy. The sensitivity of FDG PET-CT has been shown to be high and so unusual areas of avidity should prompt preoperative histological confirmation.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Pancreatic cancer overview. https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/pancreatic-cancer (cited January 2019).

- 2.Yachida S, Lacobuzio-Donahue C. The pathology and genetics of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009; : 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soman AD, Collins JM, DePetris G et al. Isolated supraclavicular lymph node metastasis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a report of three cases and review of the literature. JOP 2010; : 604–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.López F, Rodrigo JP, Silver CE et al. Cervical lymph node metastases from remote primary tumor sites. Head Neck 2016; (Suppl 1): E2374–E2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha P, Bijan B. PET/CT for pancreatic malignancy: potential and pitfalls. J Nucl Med Technol 2015; : 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arvaniti M, Danias N, Theodosopoulou E et al. Quality of life variables assessment, before and after pancreatoduodenectomy (PD): prospective study. Global J Health Sci 2015; : 203–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]