Abstract

Cystic hygroma is a benign congenital malformation of the lymphatic system that occurs in children younger than two years of age. Hygroma commonly presents in head and neck but can be present anywhere. It is rarely seen in adults. We report the case of a 28-year-old woman who presented with a huge painless right-sided cystic neck swelling of 11 months duration, associated with progressive dysphagia and difficulty in breathing when lying supine or on her left side. Clinically, the swelling occupied both right anterior and posterior triangles of her neck with impalpable right carotid pulsations. Computed tomography revealed a cystic mass lesion. The mass was excised totally through right supraclavicular incision, after identification of the great auricular, spinal accessory and phrenic nerves. Paraffin section confirmed the diagnosis of cystic hygroma. After an uneventful postoperative period the patient was discharged and has had no recurrence to date.

Keywords: Adult, Giant cystic hygroma, Lymphangioma, Neck

Introduction

Cystic hygroma is a benign congenital malformation of the lymphatic system that occurs as a result of sequestration or obstruction of the developing lymphatic vessels.1,2 It usually affects children under two years of age, but is quite rare in adults. Clinical presentation depends on the location, size and rate of growth of malformation.3–5 Diagnosis in adults is considered to present a greater challenge than in children, and final diagnosis is usually based on postoperative histology. There are few reports of adult cervicofacial cystic hygroma in the English language literature and the optimum management of these lesions is still a matter of debate.6 We report a case of cystic hygroma in the neck, in a 28-year-old woman, which was totally excised.

Case history

A 28-year-old woman presented with a painless large swelling in right side of her neck, which had started to appear only 11 months before she presented to us. The swelling was small in size and had progressively increased in size to such a degree as to cause dysphagia and difficulty in breathing, especially when she lay on back or on her left side. There was no history of trauma or recent upper respiratory infections and no past history of similar neck mass.

Local examination of the neck revealed a cystic swelling measuring approximately 15 × 16 cm, which occupied both right anterior and post triangles (Fig 1), extending from just below the angle of the mandible into the supraclavicular fossa inferiorly. The horizontal extension was from midline anteriorly to paraspinal line posteriorly and it did not move with deglutition. The mass had a globular surface and ill-defined edges. It was soft to firm in consistency and translucent on transillumination, but was not tender or compressible.

Figure 1.

Cystic hygroma occupied almost the whole right side of the neck.

No palpable lymph nodes were present on either side. There was no audible bruit. The patient had no neurological deficit. Other systemic reviews were unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations were within the average range. Chest x-ray showed a right-sided soft-tissue neck mass affecting the trachea, which had shifted to the left side (Fig 2). Ultrasonography revealed a huge cystic lesion in the right lateral aspect of the neck with septations and turbid content.

Figure 2.

Chest x-ray shows the soft tissue shadow of the cystic hygroma on the right side of the neck with mass effect on the trachea.

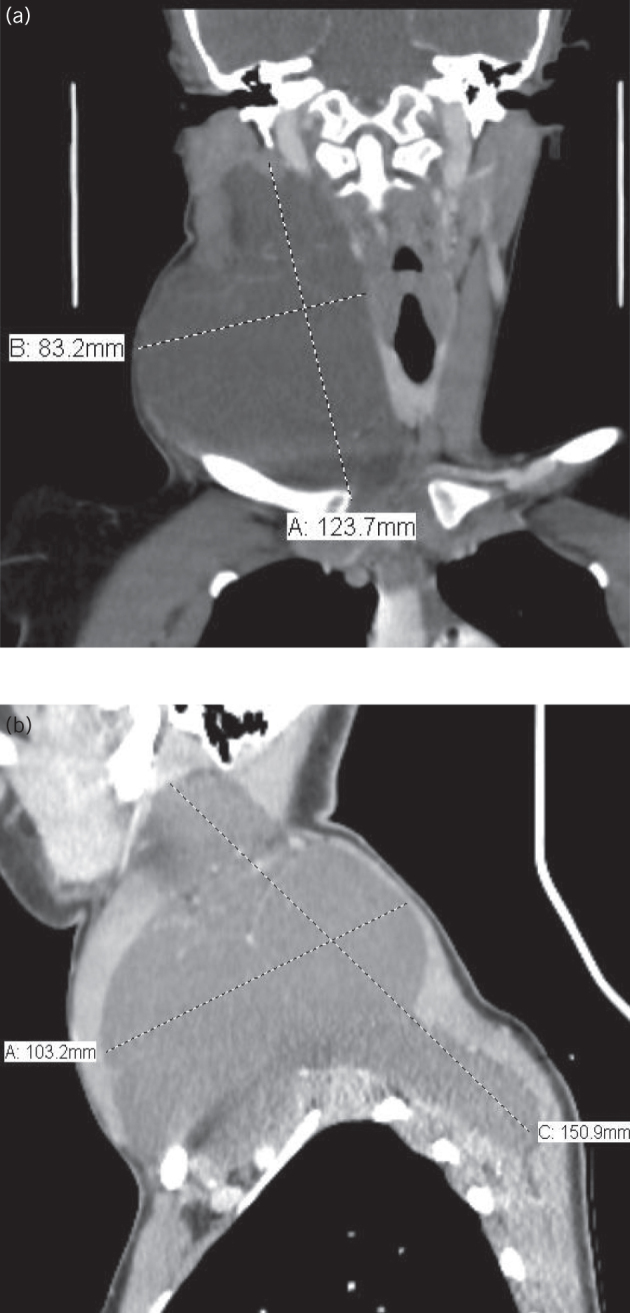

Contrast enhanced computed tomography of the neck and chest showed a 15 × 10 × 8 cm multiloculated cystic lesion of near water density occupying both right anterior and posterior triangles of the neck, which caused a mass effect over right sternocleidomastoid muscle, carotid artery, internal jugular vein, larygopharynx and trachea (Fig 3). There was no evidence of lung lesion causing lymphatic obstruction. The picture was highly suggestive of cystic hygroma. Thus, after informed consent had been taken, we proceeded for total surgical excision (Fig 4).

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the neck shows the approximate dimensions of the cystic hygroma; a) coronal view; b) sagittal view.

Figure 4.

Dissection of the cystic hygroma with the harmonic scalpel.

Under general anaesthesia with the head extended and tilted to left side, a right supraclavicular skin incision was made, including the skin, platysma and investing layer of deep fascia. The sub-platysmal flaps were dissected until the angle of the mandible was reached superiorly, medially to the midline and inferiorly to the clavicle.

After identification of the multicystic swelling, using blunt and finger dissection, the mass was dissected from over the carotid sheath medially and from the submandibular gland superiorly. The cyst extended down into both right supraclavicular and infraclavicular regions, from where it was also dissected from the apex of the lung.

The cyst extended into and down the posterior triangle. It was dissected from the subscapularis and trapezius muscles and resected totally with an intact capsule (Fig 5). During dissection, the right spinal accessory, great auricular and phrenic nerves, and the trunks of the brachial plexus were identified and safeguarded. Haemostasis was achieved and a suction drain inserted. The postoperative course was uneventful. The drain was removed on the third day and patient was discharged home. Histopathology revealed a multicystic lesion lined by a single layer of flattened epithelium consistent with cystic hygroma.

Figure 5.

The totally excised cystic hygroma with intact capsule.

The patient did not report any recurrence on follow-up over more than one year (Fig 6).

Figure 6.

The neck scar, two months following surgical excision.

Discussion

Cystic hygroma, also known as lymphangioma, is a congenital condition of the lymphatic system. It was originally reported by Redenbacher in 1828 and the name cystic hygroma was first used by Wernher in 1834.4 A failure of communication between the lymphatic and the venous pathways leads to the accumulation of lymph.7 However, the aetiology for cystic hygroma arising in adults is controversial and it is thought to be an acquired process like infection, trauma (including surgery) or lymphatic obstruction.8–10

Malignancies have been identified as precipitating factors for acquired cystic hygroma, which is one of the more unusual differential diagnoses of cystic neck lesions in adults.11 Most cystic hygromas present in utero or in infancy and most of the literature on management considers paediatric cases.6 The effect of these lesions depends on their locations and relationship with surrounding structures, although the most common adult presentation is of a painless lump in an otherwise asymptomatic patient.12

Clinical presentation depends on the location, size and rate of growth of the hygroma. Extensive lesions in the floor of mouth, oropharynx or in the neck can lead to pressure manifestations such as dysphagia when compressing the oesophagus or dyspnoea due to tracheal or laryngeal compression.5 The most distressing symptoms in our patient were caused by the pressure effect of the hygroma in the form of dysphagia and postural shortness of breath.

Various diagnostic modalities have been mentioned in the literature. Imaging methods such as ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT) have been used prior to treatment, although imaging preferences vary according to their cost, convenience and resolution.5 Preoperative imaging is important to look for intrathoracic extension, which is present in 10% of cases.13 Although in our patient the diagnosis was made clinically and supported by the ultrasound, we performed CT for better anatomical mapping and planning for the surgical approach.

Several staging and classification systems have been employed for better diagnosis and management.5 Smith et al described lymphatic malformation as microcystic, macrocystic or mixed variant, with macrocystic containing cysts more than 2 cm in diameter.14 A classification based on CT, anatomical location and histology was proposed by McGill and Mulliken in 1993 and is clinically relevant.15 Type I malformations or classic cystic hygroma are macrocystic and develop below the mylohyoid muscle. They involve the anterior and posterior triangles of the neck. Type II malformations are microcystic and invasive and are found in the neck above the level of the mylohyoid. They usually involve the lip, tongue and oral cavity and are difficult to resect. According to the latter classification, our patient is type 1 cystic hygroma. There have been reports of spontaneous regression of fetal cystic hygroma.16 This is, however, an uncommon event in adults. Medical therapy using intralesional sclerosants such as ethanol, quinine, bleomycin and OK-432 (pacibanil) have been tried for the treatment of cystic hygroma but their use is limited by the high recurrence rate, rapid increase in size of the hygroma, with inflammation and alteration of normal tissue planes and lack of tissue sample for definitive histological diagnosis.17 Intravenous cyclophosphamide has been used, with some success, in recurrent lesions following surgery.18

Surgical management is the mainstay of treatment of adult-onset cervical cystic hygroma and is based on the principle of meticulous and complete dissection of the cyst from adjacent tissues to prevent recurrence.2

As placement of skin incision in the neck region should follow the Langer’s lines as any part in the body surfaces, for best osmosis to be achieved we chose a low transverse (supraclavicular) neck incision, although the dome of the mass was in the mid-neck. The advantage of the mid-cervical neck incision or over the mass incision is that it provides good exposure to the upper- and lowermost part of the cyst, without undue tension, retraction or compromise of the flaps; however, it would be cosmetically unsatisfactory to the patient.

We preferred the low transverse supraclavicular incision as this is cosmetically more acceptable than highly located incisions and can be easily hidden under clothing. Its main challenge was in reaching the uppermost part of the cyst without jeopardising the upper flap by excessive traction.

The five intraoperative techniques (asepsis, absence of tension, accurate approximation, avoidance of raw surface and atraumatic tissue handling) are crucial to improve the aesthetic outcome of the surgical wound.19

Preservation of normal neurovascular structures of the neck is essential. Unlike the congenital variety of cystic hygroma, the adult-type lesions are well defined, making complete surgical excision more feasible.2 In our patient, we chose the surgical option as she had pressure manifestations on her aerodigestive ways due to the large size of the hygroma. Surgery was straightforward, with complete preservation of vital neck structures, with no postoperative complications, and no recurrence has been reported to date.

Conclusion

Acquired cystic hygroma in adults is a rare condition with variable presentation. The mainstay of treatment is complete excision. Continued reporting of cystic hygroma in adults will help to elucidate various presentations, diagnostic dilemmas, management options and complications. This case contributes to the body of literature in the diagnosis of neck masses in adults.

References

- 1.Bloom DC, Perkins JA, Manning SC. Management of lymphatic malformations. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; : 500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naidu SI, McCalla MR. Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck in adults: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2004; : 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasapoĝlu F, Yildirim N. Cystic hygroma colli in adults: a report of two cases, one with atypical location. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg 2008; (5): 326–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman BE, Kendall K. A unique case of the rapid onset of a large cystic hygroma in the adult. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg 2001; (3): 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dokania V, Rajguru A, Kaur H et al. Sudden onset, rapidly expansile, cervical cystic hygroma in an adult: a rare case with unusual presentation and extensive review of the literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2017; : 1061958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gow L, Gulati R, Khan A, Mihaimeed F. Adult-onset cystic hygroma: a case report and review of management. Grand Rounds 2011; : 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallick KC, Khatua RK, Routray S, Lenka A. Cystic hygroma in adults: a rare case report. J Evolution Med Dental Sci 2014; (10): 2561–2564. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy TL. Cystic hygroma: lymphangioma: a rare and still unclear entity. Laryngoscope 1989; (10 part 2 Suppl 49,): 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nosan DK, Martin DS, Stith JA. Lymphangioma presenting as a delayed posttraumatic expanding neck mass. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg 1995; (3): 186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleason TJ, Yuh WTC, Harris KG et al. Traumatic cervical cystic lymphangioma in an adult. Ann Otolol Rhinol Laryngol 1993; (7): 564–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balogun OS, Osinowo AA, Afolayan MO, Olajide TO. Surgical management of acquired cervical cystic hygroma in a nigerian adult. J Case Rep 2017; (3): 260–263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schefter RP, Olsen KD, Gaffey TA. Cervical lymphangioma in the adult. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985; : 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morley SE, Ramesar KCRB, Macleod DAD. Cystic hygroma in an adult: a case report. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1999; (1): 57–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith RJ, Burke DK, Sato Y et al. OK-432 therapy for lymphangiomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (11): 1195–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oakes MJ, Sherman BE. Cystic hygroma in a tactical aviator: a case report. Mil Med 2004; (12): 985–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson WJ, Katz VL, Thorp JM. Spontaneous resolution of fetal nuchal cystic hygroma. J Perinatol 1991; : 213215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong PQ, Xhi FX, Li R et al. Long-term results of intratumorous bleomucin-A5 injection for head and neck lymphangioma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodnone 1998; : 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner C, Gross S. Treatment of recurrent suprahyoid cervico-facial lymphangioma with intravenous cyclophosphamide. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1994; (4): 325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Son D, Harijan A. Overview of surgical scar prevention and management. J Korean Med Sci 2014; (6): 751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]