Abstract

Appropriate intervention needs to support families and consider them as a part of rehabilitation program. Parents who have high self-efficacy are more likely to put their knowledge and skills into action and have positive interactions with their children. In addition, there has been a positive relation between parental involvement and child educational success. The aim of present study was evaluating maternal perception of both self-efficacy and involvement between mothers of children with hearing aid and cochlear implant via Scale of Parental Involvement and Self Efficacy (SPISE) and exploring relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parental involvement and child factors. 100 mothers of children with hearing loss were available. 49 mothers participated in study, filled SPISE, and return it on time. SPISE consisted of three sections (1) demographic information, (2) maternal self-efficacy, (3) parental involvement. All cases had received at least 6 months auditory training and speech therapy. Participants included 30 (61.2%) mothers of children with hearing aid, 19 (38.8%) mothers of children with cochlear implant. ANOVA analysis showed that there is no significant difference between hearing aid (HA) and cochlear implant (CI) groups in term of self-efficacy and parent-involvement except for question 21 (comfortable in participating in individualized program) that score in HA group was significantly higher than CI group. Results of present study has practical implications for early interventionists working with families. Every early intervention program should consider families to reach maximum outcome. Early interventionists can use SPISE to evaluate parental selfefficacy and involvement and work on parents with low score to achieve the best results.

Keywords: Cochlear implant, Hearing aid, Hearing loss

Introduction

There is a high prevalence of hearing loss [1, 2]. Universal hearing screening at birth has led to early diagnosis of hearing loss [3]. It is recommended that children with hearing loss receive their hearing aid before they get six-month-old to prevent sensory deprivation as much as possible [4]. However, some children, especially with the profound hearing loss, do not benefit from hearing aids. These children can be a candidate for cochlear implantation [5, 6].

From the first diagnosis of hearing loss, parents are an integral part of device selection and aural rehabilitation program [7]. Parents are from different educational and cultural backgrounds and they are different in their reaction to their children’s hearing loss [8]. Therefore, parents play an essential role in their child’s early intervention program [9]. Appropriate intervention program needs to support families. The family should learn about hearing loss, child’s needs and be confident to be able helping their child. Parents should take in necessary information to make decisions on behalf of themselves and their children [10, 11].

Early interventionists must focus on family strength individually to make them feel confidence and competence or self-efficacy about their children’s current and future learning and development [12–14]. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to perform a particular task successfully. Self-efficacy means that a person knows about a task and perform it persistently until success is achieved [15]. In contrast, a person who is not self-efficacious may know about a task, but he/she is unable to show persistence due to self-doubt [16, 17]. Parents who have knowledge and self-efficacy can carry out prescribed intervention strategies [18]. Self-efficacy is a dynamic component and depends on specific situations and populations [19].

Parental involvement is a second critical component in the success of young children in the early intervention. Parental involvement is an environmental factor that affects early development [20]. Parents should become active decision makers. Different researchers define parental involvement differently (e.g., parents expectations of child educational success, attendance at early intervention program, how the family is comfortable in working with child) [21]. Regardless of definition, there has been a positive relationship between parental involvement and child educational success [22]. Parental involvement in the early intervention is vital for future language acquisition and educational development and pre-reading skills [23]. Desjardin (2005) defines parental involvement as following through interventions prescribed by interventionists (e.g., audiologists, speech-language pathologists, and teachers). This following included child‘s use of the sensory device and speech-language development. In addition to parents’ characteristics, child factors also influence parental involvement (e.g., late diagnosis of hearing loss) [21].

Hearing aids and cochlear implant differ in many ways. Family’s attitude towards them can be different. Most studies are about parents’ attitude and reaction in accepting sensory devices. Most et al. [24] showed that parents, in general, have a positive attitude towards cochlear implant. Other study showed that the decision to consider cochlear implantation is strongly influenced by the eligibility and by professionals’ recommendations. However, for some parents, the decision goes beyond eligibility and is determined by parental preferences, goals, values, and beliefs. This highlights the importance of careful audiologic evaluation and professionals’ awareness of and sensitivity to parental goals, values, and beliefs in evaluating the child’s candidacy [25]. Parent reactions to hearing aids, once fitted, included concerns about appearance and questions about maintenance and use, but attitudes regarding hearing aids and their perceived benefits improved over time [26]. Desjardin [21] showed that parents of children with cochlear implant have more self-efficacy and self-involvement in the early intervention program than parents of children with hearing aids.

The aim of the present study was evaluating the maternal perception of self-efficacy and involvement between mothers of children with hearing aids and cochlear implant by using Scale of Parental Involvement and Self Efficacy (SPISE).

Materials and methods

Mothers participated in this study who their hearing-impaired children were from 1 to 7 years old (mean age 4.04 years old ± 1.62 years). All subjects were in an early intervention program for children with hearing loss. All cases had been receiving at least 6 months auditory rehabilitation service at the time of the research.

100 mothers of children with hearing loss were available. 49 mothers participated in the study, filled SPISE (developed by Jean Desjardin, Moravian College, Pennsylvania), and return it on time. SPISE consisted of three sections (1) demographic information, (2) maternal self-efficacy, (3) parental involvement. Written consent was received from the parents.

In the maternal self-efficacy section, there were ten questions on a Likert- type scale (not at all (one) to very much (seven)). The parental involvement section had 11 questions on Likert- type scale (not at all (one) to very much (seven)). All questions were checked by the scale developer.

Prior to filling out the forms an audiologist and a speech-language pathologist explained the study aim and the way of replying to questions and also answered their questions to clarify scale items.

Demographic information for mothers was as follows: marital status, age, monolingual or bilingualism, level of education. Demographic information for children included age, gender, the age of hearing loss identification, the age of receiving amplification, the age of commencing early intervention and hearing loss etiology.

Statistical Analysis

Statistic data were analyzed by using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). In addition to descriptive analysis including mean and standard deviations, analytic tests including Spearman correlation and t test was used.

Results

Participants included 30 (61.2%) mothers of children with hearing aids and 19 (38.8%) mothers of children with cochlear implants. None of the children had any additional physical or mental disabilities. The age range of mothers was 23–47 years old (mean age 31.96 years old). Children in this study were from 1 to 7 years old (mean age 4.04 years old ± 1.62 years.), and all subjects were in the same early intervention program.

The academic experience of these mothers was as follows: 12 subjects did not have high school certificate (24.5%), 29 subjects had high school certificate (59.2%), eight subjects had a university education (16.3%). 46 mothers were housewives (93.9%), three mothers were employed (6.1%). 13 subjects (26.5%) were Farsi monolingual speakers and 36 subjects (73.5%) were bilingual speakers. Their second language included Azari, Lori, Kordi, and Northern.

Children hearing loss were diagnosed through universal newborn screening, newborn intensive care unit (NICU) screening, and parental self-referral.

All children had pre-lingual hearing loss Age of hearing loss identification, the age of receiving amplification and auditory rehabilitation (early intervention program) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age of hearing loss identification, age of receiving amplification and auditory rehabilitation

| Age of hearing loss identification | Age of receiving hearing aid | Age of cochlear implantation | Age of receiving auditory training | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 month | 11 (22.4%) | – | – | – |

| 1–3 months | 3 (6.1%) | 2 (4%) | – | – |

| 3–6 months | 11 (22.4%) | 10 (20.4%) | – | 1 (2%) |

| 6 months–1 years | 5 (10.2%) | 12 (24.5%) | 1 (2%) | 12 (24.5%) |

| 1–1.5 years | 5 (10.2%) | 7 (14.3%) | 2 (4.1%) | 9 (18.4%) |

| 1.5–2 years | 4 (8.2%) | 6 (12.2%) | 10 (20.4%) | 10 (20.4%) |

| 2–2.5 years | 2 (4.1%) | 3 (6.1%) | 2 (4.1%) | 6 (12.2%) |

| 2.5–3 years | 3 (6.1%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0 | 5 (10.2%) |

| 3–5 years | 5 (10.2%) | 5 (10.2%) | 4 (8.1%) | 6 (12.2%) |

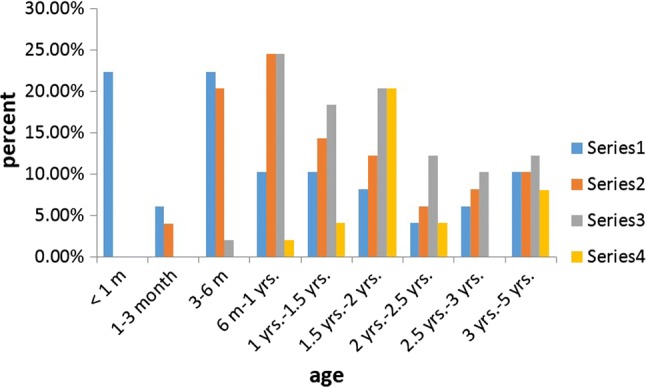

Figure 1 shows a comparison between the age of hearing loss identification (blue columns), receiving hearing aid (orange columns), cochlear implantation (grey columns) and auditory rehabilitation (yellow columns).

Fig. 1.

Age of hearing loss identification (blue columns), receiving hearing aid (orange columns), cochlear implantation (grey columns) and auditory rehabilitation (yellow columns). Blue = age of hearing loss identification, orange = age of receiving hearing aid, grey = age of cochlear implantation, yellow = age of auditory rehabilitation

None of these children received home visits. 46 (93.9%) children wore their hearing device more than 8 h a day. Table 2 shows demographic characteristics of mothers in children with hearing aid and cochlear implant. Independent t test was used for comparison between the hearing aid and cochlear implant users.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of mothers

| Cochlear implant N = 19 | Hearing aid N = 30 |

t test p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 31.89 (6.49) | 32.00 (5.19) | 0.95 |

| Mother’s education level | 1.95 (0.62) | 1.90 (1.66) | 0.80 |

| Number of family members | 3.68 (0.82) | 3.83 (0.79) | 0.52 |

| Monolingual/bilingualism | 1.32 (0.47) | 1.17 (0.46) | 0.28 |

| Age of hearing loss identification | 3.68 (2.70) | 4.37 (3.39) | 0.46 |

| Age of receiving hearing device | 4.42 (2.21) | 5.73 (2.31) | 0.056 |

| Age of starting auditory training | 3.68 (2.02) | 4.33 (1.95) | 0.27 |

Table 3 shows results (mean and standard deviation) of self-efficacy and involvement of mothers of children with hearing aids (HA group) and cochlear implant (CI group). Mean score of each question is shown separately. t test showed that there is no significant difference between CI and HA groups in term of self-efficacy and parent-involvement except for q21 (Comfortable in participating in the individualized program). The score in HA group was significantly higher than CI group for q21. p values are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

summary scores for maternal self-efficacy and involvement

| Hearing aid | Cochlear implant |

T test p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal self-efficacy: child sensory device use | Check and put on device | 5.50 (± 1.65) | 6.16 (± 1.11) | 0.13 |

| Adjust device | 4.03 (± 1.71) | 3.95 (± 1.98) | 0.87 | |

| Check listening skills | 4.67 (± 1.62) | 5.53 (± 1.26) | 0.06 | |

| Affect listening development | 5.57 (± 1.04) | 5.37 (± 1.16) | 0.53 | |

| Affect word development | 4.97 (± 0.96) | 5.37 (± 1.30) | 0.22 | |

| Maternal self-efficacy: child speech and language development | Develop child ‘s sounds | 4.73 (± 1.25) | 4.84 (± 1.38) | 0.20 |

| Conduct speech-language activities in home | 4.60 (± 0.89) | 4.95 (± 1.07) | 0.77 | |

| Positively affect child’s speech development | 5.67 (± 1.02) | 5.63 (± 1.34) | 0.22 | |

| Positively affect child’s language development | 5.27 (± 1.01) | 5.26 (± 1.44) | 0.91 | |

| Positively affect child’s overall early development | 5.03 (± 1.18) | 5.21 (± 1.13) | 0.99 | |

| Maternal involvement: Maternal involvement: child sensory device use | Check device daily | 2.00 (± 1.39) | 1.63 (± 1.25) | 0.60 |

| Put on device daily | 1.90 (± 1.37) | 1.26 (± 0.73) | 0.22 | |

| Check listening skills | 3.20 (± 1.84) | 3.11 (± 2.18) | 0.90 | |

| Use device weekly | 6.63 (± 1.29) | 7.00 (± 0.00) | 0.79 | |

| Use device daily | 6.63 (± 1.29) | 7.00 (± 0.00) | 0.87 | |

| Maternal involvement: child speech and language development | Invited to participate in early therapy | 5.77 (± 1.45) | 4.89 (± 1.66) | 0.22 |

| Comfortable participating in early therapy | No one had home visit | No one had home visit | – | |

| Comfortable following through with activities at | 4.73 (± 1.74) | 4.58 (± 1.86) | 0.06 | |

| Professionals showing listening language activities | 6.00 (± 1.48) | 5.42 (1.38) | 0.12 | |

| Include mothers in individualized program | 5.57 (± 1.43) | 5.10 (± 1.37) | 0.15 | |

| Comfortable in participating in individualized program | 4.37 (± 1.69) | 4.74 (± 1.14) | 0.01 |

Spearman correlation test showed that there is no significant correlation between SPISE score (parental self-efficacy (p value = 0.30) and involvement (p value = 0.50)) and participation in “It Takes Two to Talk Program” from Hanen center. It Takes Two to Talk Program® is a program for parents of children (birth to 5) who have language delays. This program recognizes the importance of involving parents in their child’s early language intervention and the need to help children and families as early as possible in a child’s life. It Takes Two to Talk is led by a Hanen Certified Speech-Language Pathologist who has received specialized training from The Hanen Centre.

Discussion

Family support is an essential part of early intervention for young children, but it seems that it is overlooked. SPISE provide detailed information about the relationship between children’s sensory device and mother’s knowledge and competence and their involvement in child’s early intervention program.

Findings of the present study showed no significant difference between HA and CI groups except for being comfortable in participating in the individualized program. We compare our results with Desjardin 2005. Desjardin showed that parents of CI users had a higher score in self-efficacy than parents of HA users. It was maintained that mothers of cochlear implant users think the intervention program has lower quality but show more self-efficacy ratings. This may be because until recently, early intervention team was not familiar with cochlear implant technology, and they did not have appropriate training and experience to work with children with CIs. Higher self-efficacy in mothers of children with a cochlear implant may be due to HA ineffectiveness as a sensory device for their children, and with CI they feel more cable in performing their responsibilities [21]. In the present study, there was not any significant difference between mothers of children with HA and CI. This result may be due to several factors including hearing aid technology progress, early identification of children who are candidates for CI, increased knowledge of parents about hearing loss, increased knowledge of early interventionists about CI technology. Also, both groups had received the same training, services, and consultation in the present study.

Desjardin 2005 showed that mothers of children with CI reported being more involved in developing their children’ auditory skills. It might be because mothers of children with CI feel that CI is more effective and helpful sensory device [21]. In the present study, mothers of children with CI reported being less comfortable in participating in their child’s intervention program. It might be due to several factors including being unfamiliar with CI and/or individual activities needed in training sessions. Another reason is that families may feel that after cochlear implant they do not need to participate in early intervention program because they have unreasonably high expectations from a cochlear implant. It seems parents of children with cochlear implant need special consultation for developing realistic expectations before implantation.

About the participation in “It Takes Two to Talk” workshop, there is no difference between two groups of mother and it may be due to the family-centered approach of the early intervention program they receive.

Conclusion

Results of the present study have practical implications for early interventionists working with families. Every intervention program should consider families to reach a maximum outcome. Early interventionists can use SPISE to evaluate parental self-efficacy and involvement and work on parents with a low score to achieve the best results.

References

- 1.Darouie A, Tehrani LG, Pourshahbaz A, Rahgozar M. The effect of experience on listeners’ judgment about speech intelligibility of hearing impaired children. JOEC. 2018;4:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (2012) WHO global estimates on prevalence of hearing loss. Retrieved 10 Oct 2012

- 3.Thompson DC, McPhillips H, Davis RL, Lieu TA, Homer CJ, Helfand M. Universal newborn hearing screening: summary of evidence. JAMA. 2001;286(16):2000–2010. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.16.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Council NR. Hearing loss: determining eligibility for social security benefits. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradham T, Jones J. Cochlear implant candidacy in the United States: prevalence in children 12 months to 6 years of age. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(7):1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdollahi FZ, Ahmadi T, Joulaie M, Darouie A. Cochlear implant in children. Glob J Otolaryngol. 2017;8(5):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couto MIV, Carvalho ACM (eds) (2013) Factors that influence the participation of parents in the oral rehabilitation process of children with cochlear implants: a systematic review. In: CoDAS, SciELO Brasil [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Eyalati N, Jafari Z, Ashayeri H, Salehi M, Kamali M. Effects of parental education level and economic status on the needs of families of hearing-impaired children in the aural rehabilitation program. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;25(70):41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahoney G, Wiggers B. The role of parents in early intervention: implications for social work. Child Sch. 2007;29(1):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hearing JCOI, Pediatrics AAO, Association AS-L-H Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):798–817. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushalnagar P, Mathur G, Moreland CJ, Napoli DJ, Osterling W, Padden C, et al. Infants and children with hearing loss need early language access. J Clin Ethics. 2010;21(2):143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruder MB. Early childhood intervention: a promise to children and families for their future. Except Child. 2010;76(3):339–355. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DesJardin JL. Family empowerment: supporting language development in young children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Volta Rev. 2006;106(3):275. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moeller MP, Carr G, Seaver L, Stredler-Brown A, Holzinger D. Best practices in family-centered early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing: an international consensus statement. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2013;18(4):429–445. doi: 10.1093/deafed/ent034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conner M, Norman P. Predicting health behaviour. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Social learning theory of aggression. J Commun. 1978;28(3):12–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandy AM (2004) Examining the impact of parental self-efficacy on the early intervention process for families with a child who is deaf or hard of hearing. Independent Studies and Capstones. Paper 695. Program in Audiology and Communication Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine. https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1684&context=pacs_capstones

- 19.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122. [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Nokali NE, Bachman HJ, Votruba-Drzal E. Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Dev. 2010;81(3):988–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desjardin JL. Maternal perceptions of self-efficacy and involvement in the auditory development of young children with prelingual deafness. J Early Interv. 2005;27(3):193–209. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desforges C, Abouchaar A. The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievement and adjustment: a literature review. Nottingham: DfES Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calderon R. Parental involvement in deaf children’s education programs as a predictor of child’s language, early reading, and social-emotional development. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2000;5(2):140–155. doi: 10.1093/deafed/5.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Most T, Wiesel A, Blitzer T. Identity and attitudes towards cochlear implant among deaf and hard of hearing adolescents. Deaf Educ Int. 2007;9(2):68–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Bain L, Steinberg AG. Parental decision-making in considering cochlear implant technology for a deaf child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(8):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sjoblad S, Harrison M, Roush J, McWilliam R. Parents’ reactions and recommendations after diagnosis and hearing aid fitting. Am J Audiol. 2001;10(1):24–31. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2001/004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]