Abstract

Cutibacterium acnes is an abundant skin commensal with several proposed mutualistic functions. A protein with strong antioxidant activity was recently identified from the C. acnes secretome. This protein, termed RoxP, facilitated aerobic bacterial growth in vitro and ex vivo. As reducing events naturally occurred outside of the bacterial cell, it was further hypothesized that RoxP could also serve to modulate redox status of human skin. The biological function of RoxP was here assessed in vitro and in vivo, through oxidatively stressed cell cultures and through protein quantification from skin affected by oxidative disease (actinic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma), respectively. 16S rDNA amplicon deep sequencing and single locus sequence typing was used to correlate bacterial prevalence to cutaneous RoxP abundances. We show that RoxP positively influence the viability of monocytes and keratinocytes exposed to oxidative stress, and that a congruent concentration decline of RoxP can be observed in skin affected by oxidative disease. Basal cell carcinoma was moreover associated with microbial dysbiosis, characterized by reduced C. acnes prevalence. C. acnes’s secretion of RoxP, an exogenous but naturally occurring antioxidant on human skin, is likely to positively influence the human host. Results furthermore attest to its prospective usability as a biopharmaceutical.

Introduction

The age-old relationship between bacteria and the human body is vital but ambiguous. While most bacteria can be labelled either harmful or beneficial to our health, certain multifaceted species appear to be both1. Transcending our current definitions of “pathogen” and “commensal”, Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes2), is an abundant skin colonizer thriving in the nutritious environment of sebum rich skin3. Albeit causing no symptoms in the majority of carriers, this Gram-positive, facultative anaerobe holds a proposed pro-inflammatory role in acne vulgaris pathogenesis4 and is, due to its biofilm-forming capacity5, frequently isolated from various orthopedic implant-associated infections6–8. Despite being a well-established opportunistic pathogen, there is a link between the autoimmune disorder psoriasis and low C. acnes prevalence9,10 indicating that its presence is also associated with mutualistic interactions11. Consistent with this line of reasoning, we were recently able to characterize a protein, unique to C. acnes, with a suggested role in maintaining skin redox homeostasis12.

An asymmetrical distribution of hair follicles, sweat glands and sebaceous glands in our skin generates an array of distinct niches that nurtures a microbiota of great diversity3, highly comparable to that of our intestinal microbiota13. While dry areas tend to harbor a relatively small bacterial load consisting mainly of Proteobacteria, Flavobacteriales or Bacteroidetes, more moist and sebaceous regions, like that of our face and upper trunk, typically sustain larger quantities of Corynebacteria, Staphylococci and Propionibacteria3,14. As widely recognized for our gut microbiome15, this resident microbiota influences immunological responses which are, although occasionally troublesome, ultimately required to maintain cutaneous health16. For instance, Staphylococci species are capable both of soothing inflamed areas and aggravating protective pro-inflammatory responses through lipoprotein modifications17. S. epidermidis is furthermore able to alter the composition of the surrounding microbiota by production of antimicrobial compounds, and a complex interplay subsequently arises between our skin and the numerous bacterial species it harbors. As we increase our understanding of bacterial virulence, an accumulating amount of evidence links dysbiosis to various human disease states, including metabolic disorders18, atopic conditions19 and cancers20.

Combined with an emerging notion of strain-specific virulence, this challenges the concept of bacterial pathogenesis as we know it. Specific types or isolates of C. acnes can now be linked to disease21–23. The conventional C. acnes clades IA, IB, IC, II and III24–26, can be further subdivided into distinct sequence types based on single locus sequence typing27. These separate evolutionary lineages have repeatedly been shown to differ in their expression of virulence determinants28–30, including the secreted antioxidant RoxP (Radical oxygenase of Propionibacterium acnes)12. Phylotype IA strains are for example better adapted to the oxygen and fatty acid-rich environment of human skin, while phylotype IC and II strains remain closer linked to opportunistic infections of deeper tissues31.

Perhaps to a bigger extent than any other organ, our skin is also subjected to high quantities of reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from ordinary metabolic reactions, cosmetics and a continuous exposure to UV irradiation from the sun. These are notorious carcinogens and have lately generated a mounting public interest in relation to antioxidant-rich food. Under physiological conditions, an endogenous production of reducing agents such as glutathione S-transferase and glutathione reductase32, protects our skin from excessive oxidative stress. Under pathological conditions however, the regeneration of ROS may become too great and consequently contribute to the pathogenesis of for example psoriasis33 or skin cancer34. In analogy to the production of antioxidants in human cells, evolution in this hostile milieu has likely favored the selection for several reducing agents within C. acnes35,36. When the bacterial secretome was first published in 2010, it disclosed a previously unidentified protein expressed in abundance by all C. acnes isolates37. This protein, RoxP, was later shown to exhibit high antioxidant activity12. RoxP proved imperative for efficient bacterial growth in aerobic settings in vitro, as well as for the colonization of human skin ex vivo, ultimately raising the question as to whether it might have a corresponding role in vivo.

Here, we describe phylotype-specific roxP expression patterns and characterize RoxP activity on a molecular level. We investigate its biological function in vitro through human monocyte/keratinocyte cell cultures, and in vivo through quantification of cutaneous RoxP in oxidative skin diseases (actinic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma38). The potential role of C. acnes and RoxP in limiting susceptibility towards oxidative skin disease is discussed.

Methods

Bacterial strains and cultivation

C. acnes isolates, representative of type I, II and III strains, were grown at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions in Wilkins-Chalgren anaerobe broth (WC) until reaching either exponential (1–3 days) or stationary phase (5–7 days). Further information about specific C. acnes strains5 or their respective RoxP homologs12 can be found elsewhere.

qPCR analysis of roxP gene expression

The RNA content of exponential and/or stationary phase C. acnes cultures was extracted using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen) complemented with Bacteria Protect Reagent (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Resulting RNA concentrations were measured using NanoDrop® (Saveen Werner) and samples stored in −20 °C until later use.

The relative abundance of roxP and gapdh transcripts was determined through quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using Power SYBR Green RNA-to-Ct 1-step Master Mix (ThermoFisher) mixed 1:1 (v/v) with 10 ng RNA and 100 nM primers (roxP: 5′-GCATCTAGCCCTCTCACCAT-3′ and 5′-CTGAGAGTCCGGTAGGTGGT-3′; gapdh: 5′-GCATCATGACTACCGTCCAC-3′ and 5′-CGGTGGTCTCCTTAGAGGTC-3′) in nuclease free water. Plates were run with reverse transcription for 30 min at 48 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95 °C alternating with 1 min at 60 °C, on an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad). Results were interpreted via double delta Cq analysis, using the recorded values for C. acnes strain 266 as a reference. The experiment was run in biological and technological duplicates.

Generation of a RoxP expressing yeast vector

A truncated version of roxP (amino acid residues 24–161, omitting the N-terminal signal peptide) from C. acnes strain KPA171202 was amplified (primers: 5′-GGCTGAAGCTGAATTCACACCCATCGATGAGAGCCAAC-3′ plus 5′-GATGATGATGGTCGACTCCTGCTGCGCCGTTGAGGGCGGGATCCACC-3′) to generate a roxP fragment containing a C-terminal GAAG linker, and cloned into the EcoRI and SalI sites of the pPICZαA vector (ThermoFisher Scientific). Sequence verified linearized plasmids were used to transfect SuperMan5 Pichia pastoris (Biogrammatics).

Expression of recombinant RoxP (rRoxP)

A generated SuperMan5 Pichia pastoris strain harboring the formerly described vector, was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C in YPD media supplemented with 50% glycerol. For efficient expression of recombinant protein, thawed freeze cultures were grown in a Buffered Glycerol-complex medium (BM* (70%, v/v), 0.5 M potassium buffer pH 6.0 (10%, v/v), YNB (1.4%, w/v), >99% glycerol (1%, v/v), Biotin (4 × 10−7%, w/v)) for 24 h prior to being re-suspended in Buffered Methanol-complex medium (BM* (70%, v/v), 0.5 M potassium buffer pH 6.0 (10%, v/v), YNB (1.4%, w/v), 99.8% methanol (1.5%, v/v), Biotin (4 × 10−7%, w/v)). Cultures were subsequently maintained in a shaking incubator (30 °C, 180 rpm) for 5 days with the continuous induction of roxP achieved through addition of methanol (1%) every 24 h.

*BM: Yeast extract (1.4%, w/v), Peptone (2.9%, w/v), CAS amino acids (1.4%, w/v).

Purification of rRoxP

Sterile filtered yeast supernatant was loaded onto nickel columns (His Gravitrap™, GE Healthcare) and eluted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using an imidazole buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole). Purified protein was immediately re-buffered in sodium phosphate (20 mM, pH 7.4) by means of dialysis (MWCO: 6–8 kDa, Novagen®), after which the protein concentration was spectrophotometrically determined through NanoDrop® (Saveen Werner) and sample purity via a 15% SDS-PAGE.

Cryogelation

The method used for cryogelation has been previously described by Ertürk et al.39. Briefly, the functional monomer N-Methacryloyl-l-histidine methyl ester (1 mM) and template RoxP (1 mM) were dissolved in deionized water for precomplexation. 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (20 mM) was simultaneously prepared (1:1 v/v). Monomer solutions were then mixed with an equal volume cross-linking agent, N,N’-Methylenebisacrylamide (final concentration 90 mM), and the reaction mixture purged with nitric oxide. Polymerization was subsequently initialized by the addition of ammonium persulfate (4.4 mM) and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylene ethylenediamine (0.125%). The resulting solution was aliquoted into 4 × 5 ml plastic syringes (Ø = 1.3 cm) with closed lower outlets and immediately placed in 14 °C for 24 h. After being thawed, columns were initially washed with H2O and template protein later removed with an imidazole buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). Elution was discontinued when no RoxP could be detected in the flow through (spectrophotometrically determined at 280 nm).

Purification of native RoxP

The ammonium sulphate (80%) protein fraction of stationary phase C. acnes AD24 was passed through a pre-equilibrated cryogel column using a peristaltic pump (1 mL/min) under continuous stirring for 1 h. Bound RoxP was eluted using imidazole buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.4) and the resulting protein concentration and sample purity analyzed through NanoDrop® (Saveen Werner) and a 15% SDS-PAGE, respectively.

ABTS radical cation assays

The reduction of pre-formed ABTS radical cations in the presence of RoxP was analyzed using a spectrophotometric assay previously described by Re et al.40. 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) (Sigma –Aldrich) was initially dissolved in ddH2O to a concentration of 7 nM. Potassium persulfate (MERCK) was subsequently added to a final concentration of 2.45 mM and the resulting solution kept dark and incubated overnight at RT. Formed ABTS radicals were diluted with PBS (pH 7.4) until reaching an absorbance of approximately 0.7 at 734 nm. Antioxidants (1.7 μM) were added (1:9 v/v) and the absorbance spectrum 500 to 900 nm recorded after 30 sec.

Cell culturing

Human keratinocytes (HaCat cells) were grown in SFM medium supplemented with L-glutamine, EGF (epidermal growth factor) and bovine pituitary extract (Gibson, Invitrogen) until 90% confluency in 96-well plates (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark). Human monocytes (THP-1 cells, kindly provided by Dr. Arne Egesten) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with Glutamax-1 (Gibco®), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 10% fetal calf serum (ThermoFisher Scientific). All cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

MTT assay

HaCat cells cultured to 90% confluency, or THP-1 cells (1.2 × 106 cells/well) in a 96-well plate were treated with 2 mM paraquat (Sigma-Aldrich) and/or 5 μM RoxP for 24–48 h. HaCat cells were kept in their culture medium, while monocytes were transferred to a HEPES-HBSS (Hank’s balanced salt solution) buffer at pH 7.4. Viability was measured by the addition of 0.5 mg/ml 3-(4,5-demethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) for 1–5 hours. The cells were washed with PBS followed by the addition of DMSO. The samples incubated for 30 minutes and absorbance at 550 nm was measured using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (BioRad).

Collection of skin swabs

Samples were collected between November 2016 and May 2017 at the Department of Dermatology at Lund University Hospital, Sweden. Patients (n = 54, aged between 50–70) presenting with clinically suspected actinic keratosis or superficial/nodular basal cell carcinoma of the face, neck, upper chest or shoulder regions, were asked for participation (Supplementary table 1). Individuals were swabbed (Venturi Transystem, Copan, Italy) with buffer pre-soaked swabs for 30 sec at lesional regions (4 cm²) and for 30 sec at an anatomically identical healthy site (4 cm²). Swabs were gently shaken in their liquid storage solution, stored at 4 °C o/n, and then prepared for analysis. Exclusion criteria included patients with: applied make up, newly washed face (<1 h), diabetes, cognitive impairment, other active skin disorders, ulcerated tumors, immunosuppression, ongoing/newly ended antibiotic or corticosteroid treatment (systemic or topical, < 4 weeks). The study was approved by the ethical committee in Malmö/Lund (2016/465), and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Analysis of RoxP concentration in skin swab samples using a capacitance biosensor

The abundance of RoxP in samples taken from either healthy volunteers or AK/BCC patients were analyzed on a capacitive biosensor, applying a molecular imprinting technique previously described by Ertürk et al.41. Accounting for any potential background, a calibration curve was initially obtained from RoxP spiked (0.14–0.71 mM) mock skin swabs (Venturi Transystem, Copan, Italy), diluted 1:100 (v/v) in sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). Cells and debris from patient swabs were subsequently removed through centrifugation (15 min, 4000 x g), supernatant diluted 1:100 (v/v) in sodium phosphate buffer, and eventually injected into the capacitive system in triplicates.

Preparation of DNA from skin swabs

Cotton sticks with skin swabs from patients and healthy individuals were stored at 4 °C o/n. Cellular material was collected from the liquid storage buffer through centrifugation (5000 g, 10 min), and DNA extracted using Qiagen DNeasy. Quantity and quality of DNA extractions were evaluated by NanoDrop® (Saveen Werner).

DNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

To determine the skin microbiome, the V1–V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified and amplicons were subjected to deep sequencing using Illumina technology, performed by Eurofins (Germany) and processed using the Mothur software v1.39.1 and the MiSeq SOP with some modifications. Initially, the paired-end reads were combined using the command “make.contig42”. The combined reads were then trimmed off the primer sequence and sequences containing ambiguous bases or containing longer stretched of homopolymers than eight were discharged from further analysis. The reads were afterwards aligned against the Silva reference alignment v128 and the resulting alignment was filtered so that all reads only overlapped the same region. To further reduce the number of sequencing errors, a pre-clustering step implementing a pseudo-single linkage algorithm originally developed by Huse et al.43 with the “diff” variable set to four was performed. Chimeras were removed using the build-in version of the UCHIME algorithm in Mothur44. Lastly, all singletons, duplicates, and triplicates were removed before final analysis to preclude inclusion of sequences from potential contamination or sequence errors that have not been detected in the previous steps. The resulting reads were then classified with the classify.seqs command using the Bayesian method and the taxonomic outline v14.51 from the Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD) (http://www.homd.org/) with a manual inclusion of relevant skin bacteria45. The confidence cut-off was set to 80%. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) coupled with effect size measurement (LEfSe) to detect differentially abundant bacterial taxa (phyla, genera, species) between groups. The alpha values for the factorial Kruskal–Wallis and pairwise Wilcoxon tests were set to 0.05 and the LDA score threshold for discriminative features was set to 3.5. The online version of the LEfSe program was used46.

To determine phylotypes of the C. acnes population in skin swab samples we used the SLST approach established previously29. The SLST amplicons were subjected to MiSeq sequencing, performed by Eurofins (Germany). All high-quality sequence read pairs were assigned to SLST alleles; all currently known SLST alleles are accessible on www.medbac.dk/slst/pacnes.

Results

Expression of roxP is dependent on C. acnes phylotype

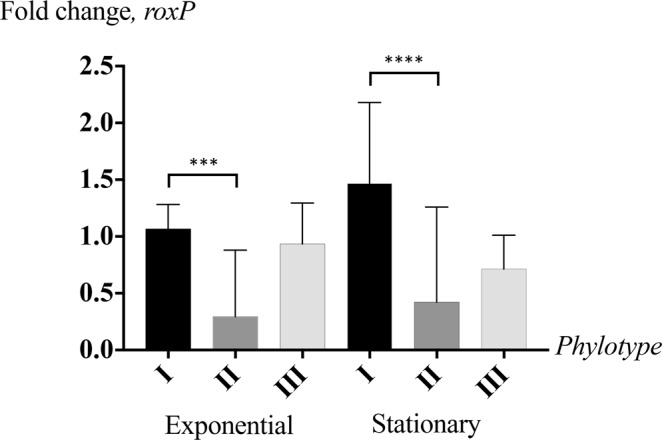

Former studies have demonstrated phylotype-specific expression patterns of several C. acnes host-interacting factors23,47. We therefore sought to determine roxP expression rates through quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) in all major phylotypes. C. acnes isolates identified as phylotype I displayed significantly higher expression levels of roxP compared to most phylotype II strains (Fig. 1). Sequencing of the respective roxP upstream regions revealed a base substitution in type II strains, affecting the - 35 region of the predicted roxP promoter, potentially able to negatively influence transcription rates (Fig. S1). Comparison of 155 sequenced C. acnes genomes revealed that most phylotype I strains shared the same roxP upstream region, associated with high expression, while the roxP upstream region of most phylotype II strains was distinct (Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

C. acnes phylotype I express significantly more roxP than other phylotypes, particularly during stationary phase growth. RNA was extracted from exponential and/or stationary phase C. acnes cultures, representative of type I (n = 6), type II (n = 5) and type III (n = 2) strains. qPCR quantifications of roxP mRNA were run in biological and technological duplicates, normalized against gapdh transcripts and evaluated using double delta Cq analysis. Grouped with their respective phylotypes, statistical significance was subsequently determined through a student’s t-test. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

As RoxP had previously proven beneficial for C. acnes regarding its oxygen tolerance12, we proceeded to investigate aerobic/anaerobic growth capacities of the utilized strain cohort. Whereas an increased roxP expression, exhibited by most phylotype I strains, correlated with an ability to grow equally well in oxic and anoxic environments, low roxP expression resulted in reduced or delayed growth in oxygen-rich settings (Fig. S3).

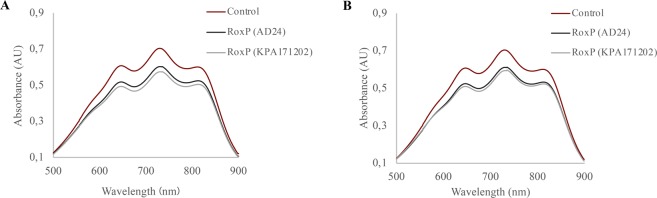

RoxP homologs display comparable antioxidant activities

Marked variations in roxP expression levels between different C. acnes phylotypes compelled us to examine, and compare, the reducing activity of different RoxP homologs (Fig. S4). Although RoxP is highly conserved, with 99–100% amino acid identity in the majority (∼93%) of isolates, a subset of strains (∼7%) classified as C. acnes phylotype II and III express a more distantly related protein, with approximately 83% amino acid identity12. The main variant could here be successfully isolated from (type IB) C. acnes KPA171202 culture media, and the less common homolog from (type II) C. acnes AD24 culture media. The latter was purified using macroporous cryogels imprinted with recombinant RoxP (Fig. S5), after which the protein identity was verified through western blot analysis (data not shown). As demonstrated by a decreased absorbance at 734 nm, the two homologs were able to reduce the cationic ABTS+ substrate with equal efficiency and, in doing so, displayed highly similar antioxidant activities (Fig. 2). Although the variant more commonly expressed by phylotype I strains displayed a continuously higher activity, the difference was only minor and not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

RoxP homologs display comparable activity. Two distinct RoxP variants, natively expressed from KPA171202 and AD24 C. acnes, were incubated with either (A) pre-formed ABTS+ radicals or (B) pre-formed ABTS+ radicals plus NaCl (150 mM). Reduction of substrate was measured as absorbance decrease at 734 nm.

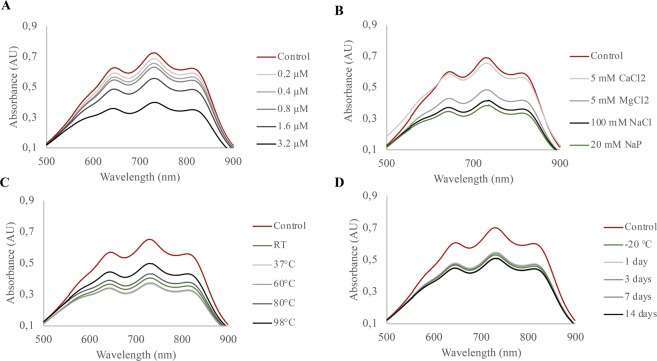

Antioxidant activity of RoxP is maintained in harsh conditions

For facultative anaerobes like C. acnes, human skin presents a hostile milieu, exposing them to fluctuating temperatures, oxygen and relatively high salt concentrations48. In order for RoxP to possess a function in vivo, the protein structure would have to withstand the same diverse conditions. RoxP displayed a concentration-dependent reducing activity (Fig. 3A), had a loss of activity in presence of CaCl2 but withstood physiological concentrations of NaCl (Fig. 3B). The protein was furthermore able to endure temperatures of above 70 °C without any significant loss of activity (Fig. 3C), as well as long-term storage in room temperature (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

RoxP antioxidant activity is highly resilient to adverse conditions. The ability of RoxP to reduce ABTS radical cations, denoted by a decrease in absorbance at 734 nm, was tested in multiple settings. Different concentrations of recombinant RoxP (rRoxP) (0.2–3.2 μM) in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) (A), rRoxP (2.7 μM) incubated with salt solutions (B), pre-heated rRoxP (2.7 μM) incubated for 20 min in temperatures ranging from RT to 98 °C and allowed to cool down to ambient temperature prior to activity measurements (C), or rRoxP (2 μM) stored at RT for up to 2 weeks (D) were added to a solution of pre-formed ABTS+ radicals and the absorbance recorded after 30 sec.

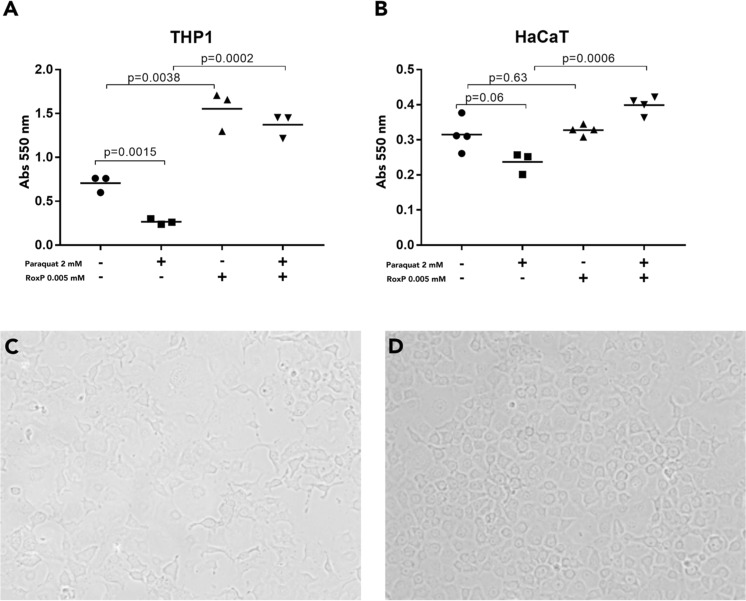

RoxP can protect human cells from oxidative damage in vitro

To investigate the ability of RoxP to reduce free radicals in a biological system, we exposed HaCat and THP-1 cells to a herbicide previously shown to promote ROS generation in human cell cultures (paraquat)49, and studied the ability of RoxP to rescue cells from lethal oxidative stress. Even at a 1:400 ratio (RoxP:oxidizer) being added in a subsequent manner, RoxP completely inhibited the negative oxidative effect of paraquat (Fig. 4). The effect was more prominent in monocytes, while keratinocytes responded less well, both to oxidation and antioxidation (Fig. 4A,B). Notably, RoxP could also increase the overall viability of human cells in the absence of an added oxidizer (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

RoxP can protect human cells from oxidative damage in vitro. Human monocyte (A) or keratinocyte (B) cell lines were exposed to oxidative stress through addition of paraquat, while adding RoxP momentarily afterwards. Cells were incubated for 24 h (keratinocytes) or 48 h (monocytes) before cell viability was analyzed through MTT assays. Representative microscopy visualizations of monocytes after paraquat (C) or paraquat + RoxP (D) are demonstrated. Statistics were calculated using a student’s t-test.

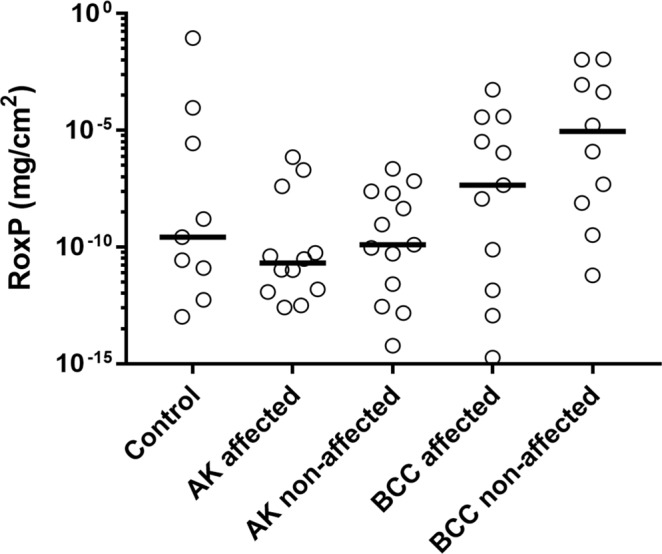

RoxP is less abundant in skin disease associated with oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is considered the single most influential aetiological factor in carcinogenesis of human skin50. Non-melanoma skin cancers, including squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma, display not only increased evidence of oxidative stress, but also of impaired endogenous antioxidant function51. To investigate whether an abated function of RoxP, an exogenous but naturally occurring antioxidant, might also be linked to oxidative skin disease, we studied protein abundances in actinic keratosis (AK) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Skin swabs (n = 54) were obtained from individuals with healthy skin, with the pre-cancerous condition AK and with developed BCC, at both disease-affected and non-affected regions. Samples were subsequently analyzed using a highly sensitive capacitive biosensor, previously shown to detect concentrations of as little as 8.25 ng RoxP/cm2 skin41, and the recorded capacitance changes equilibrated to a pre-established calibration curve (Fig. S6). Results were analyzed on a population (Fig. 5) and individual basis (Fig. S7). In the latter case, patients were excluded if accurate determination of RoxP concentration, in either affected or non-affected regions, were unsuccessful (data not shown). An overall higher RoxP abundance was observed among patients with BCC (Fig. 5). Individuals with AK showed a RoxP concentration decline in diseased areas, while those with BCC displayed similar levels at both affected and non-affected sites (Fig. S7).

Figure 5.

RoxP is less prevalent in skin regions with oxidative disease. Individuals with either healthy skin (control, n = 18), actinic keratosis (AK, n = 18) or basal cell carcinoma (BCC, n = 18) were swabbed at diseased (affected) and healthy (non-affected) regions. Absolute quantity of RoxP was determined by RoxP-MIP capacitive biosensor measurements. All individual data points were included in the analysis.

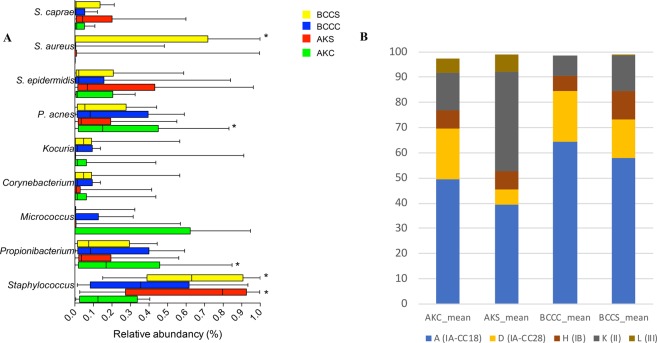

Dysbiosis in oxidative skin disease is characterized by diminished C. acnes prevalence

To determine whether the observed changes to the cutaneous RoxP concentration might also have a basis in a microbial dysbiosis (e.g. C. acnes), we studied bacterial composition in AK and BCC at the genus, species and C. acnes phylotype level. Skin swabs, trailed by 16 S rDNA amplicon deep sequencing, revealed markedly diminished Propionibacterium and elevated Staphylococcus abundances in diseased compared to healthy skin (Figs 6A and S8). A drop in C. acnes prevalence during acute stages of oxidative disease (AK) seemingly proceeded the surge in staphylococcal species, particularly S. aureus, during later stages of disease (BCC) (Fig. 6A). Further characterization of C. acnes populations through single locus sequence typing (SLST) revealed that the prevalence of specific C. acnes types was also shifted in AK- and, to a lesser extent, in BCC-affected skin (Fig. 6B). Strains belonging to C. acnes type II could more commonly be isolated from diseased skin regions, while healthy skin areas displayed a closer-to-average predominance of type I strains.

Figure 6.

Dysbiosis of the skin microbiome in AK and BCC. Box plot of the relative abundances of the five most abundant genera and four most abundant species in the four groups (A). Whiskers shows the 5–95% percentile and median values are shown as vertical lines. Differentially abundant taxa based of LefSe analysis are marked with an*. (B) Determination of relative abundancies of C. acnes phylotypes in AK and BCC. C. acnes type II abundances increase in AK-affected skin sites compared to controls (increase from 15% to 39%), whereas type IA strains decline (from 70% to 45%).

Discussion

Bacteria-derived elements directly advantageous for the human host are well-documented in the context of our gastrointestinal tract, most notably vitamin K synthesis52,53. Yet many of the benevolent factors identified from our cutaneous microbiome act indirectly, through colonization resistance54,55, rather than upon host systems themselves. Here, we study the biological effect of RoxP, a novel antioxidant secreted by the ubiquitous skin colonizer C. acnes. We show that RoxP has a direct positive influence on the viability of monocytes and keratinocytes exposed to oxidative stress in vitro, and that a (congruent) concentration decline of RoxP can be observed in skin affected by oxidative disease (AK) in vivo. We also sought to examine phylotype-specific roxP expression patterns and reducing activities of distinct RoxP homologs. An increased expression, presumably resulting in higher amounts of secreted, active RoxP, was noted among strains classified as C. acnes type I. These results were ultimately related to the earlier quantification of cutaneous RoxP, through analyses of prevalence and distribution of C. acnes (and other species) in AK/BCC-affected skin. Consistent with other findings, diseased skin regions displayed an overall diminished C. acnes population, with a striking decline in phylotype I strains.

Considerably higher roxP expression levels, indicative of enhanced oxygen tolerance, are here displayed by the skin- and acne-associated C. acnes phylotype I strains. No significant difference in reducing activity could be observed between the RoxP variants, and growth curves subsequently confirmed that elevated expression levels indeed did correlate with an overall improved aerobic growth (Fig. S3). This finding may help explain how minor genetic discrepancies between C. acnes phylotypes can impact their respective ecological preferences to such an extent31. Sequencing data namely suggests that a single base substitution in the promotor region of roxP, between C. acnes phylotype I and II (Figs S1 and S2), is influencing transcriptional activity and consequently also bacterial survival on human skin.

Activity assays were repeated under various harsh conditions, simulating in vivo settings. Despite being added at above physiological concentrations, sodium chloride did not significantly alter RoxP activity. The presence of calcium chloride however, almost completely abolished its radical scavenging ability; whether dependent on assay format, denaturing processes or stabilizing interactions, is not yet clear. Retaining more than 60% of its original activity after a 20 min exposure to 98 °C, RoxP furthermore demonstrated a level of thermostability seldomly observed for proteins derived from non-thermophilic organisms. The high stability of RoxP is desirable from both the aspect of using it diagnostically (biomarker) as well as a biologics. Though the exact molecular mechanism of RoxP remains to be characterized in detail, other enzymes involved in redox homeostasis (e.g. peroxidases) are notoriously heat resilient56, suggesting that this resistance pattern is not unique for RoxP but rather a general phenomenon for this class of proteins. Although a satisfying explanation will most likely require the elucidated three-dimensional structure, not available at present, we hypothesize that the proteins relatively minute size (∼14.6 kDa) may confer increased stability.

Further elucidating the prospective symbiotic relationship between C. acnes and its human host, the effect of RoxP was subsequently assessed in eukaryotic systems. Antioxidant addition increased the viability of monocyte/keratinocyte cell lines exposed to oxidative stress in vitro, even beyond that of the non-stressed sample. In doing so, RoxP seemingly rescued them from intrinsic stressors, most likely an immunological/metabolic based ROS production. If later confirmed in vivo, this could rationalize an involvement of C. acnes in the redox status of human skin and explain the observed prevalence decline in skin affected by oxidative disease.

The milder reaction to RoxP supplementation observed for the HaCat cell line, could theoretically be explained by an aberrant NF-κB response57, as the pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling pathway regulates cellular responses to oxidative stress58. If so, this would furthermore indicate that RoxP display evidence of immunomodulatory functions, potentially exploitable in the pharmaceutical industry. Even though the concentration used (5 μM) is greater than those previously detected on skin (8.25 ng RoxP/cm241,), it remains considerably lower than that of other antioxidants used in current skin products59, and is in no way immoderate. Additional studies are however required to determine whether RoxP indeed moderates NF-κB or other signaling pathways.

To further assess the potential influence of RoxP activity on human skin in vivo, swabs were obtained from skin affected by either the pre-cancerous condition AK or the further progressed disease state BCC. Samples were analyzed for individual (diseased vs. healthy skin) dissimilarities. Closely linked to oxidative stress50,60, AK-affected skin regions contained lower RoxP concentrations than healthy, anatomically equivalent, sites. This may indicate a predisposed vulnerability towards physiological/pathological oxidative stress in certain areas, however, the results provide no information about causality. Reduced RoxP concentrations could be either a trigger for, or result of, disease. Samples were also analyzed for population wide (patients vs. healthy individuals) differences. Results were now indicative of an overall decreased and increased RoxP abundance among AK and BCC patients, respectively. As it has been argued that antioxidant activity may aid tumor growth and metastasis61, we hypothesize that RoxP (with other cutaneous antioxidants) impede tumor formation, but facilitate survival of the cancer once formed. The cutaneous microbiota could subsequently be involved in the skin’s pathophysiological events through a ROS-scavenging activity that is both preventative and abetting of cancerous conditions. It should be noted however, that results failed to demonstrate statistical significance, potentially due to big variations in composition of the individual and local microbiota. Previously shown to detect RoxP quantities of less than 9 ng RoxP/cm241, capacitive sensors are furthermore highly sensitive instruments, prone to generate high standard deviations particularly during detection of samples including more abundant proteins (see Fig. S6).

Trends observed following quantification of RoxP in vivo, were ultimately correlated to studies of the local cutaneous microbiota, also in AK/BCC-affected skin. Here, oxidative disease was linked not only to a general decrease in Propionibacterium and C. acnes prevalence, but more specifically also to a decline of C. acnes phylotype I strains that had previously demonstrated superiority in their expression of roxP. Results therefore, once again, suggested that the advantageous effect of RoxP observed in human cell cultures in vitro, carries weight also in vivo. The secretion of RoxP from C. acnes seemingly aid our endogenous antioxidant systems, acting as a second layer of prevention and/or defense against oxidative disease (including psoriasis and skin cancer). This implies a role of RoxP in protection from UV irradiation and skin-aging processes that future studies will investigate.

Conclusion

Our work demonstrates the value of a healthy skin microbiome, in particular C. acnes due to its production of RoxP, in upholding redox homeostasis of human skin, thus protecting against development of several skin pathologies driven by oxidative stress. Succeeding studies will investigate the diagnostic and therapeutic value of this bacterial antioxidant in vivo.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Maria Allhorn is gratefully acknowledged for lending her brilliant support during ABTS+ assays and Magnus Gram plus Malgorzata Berlikowski acknowledged for their tremendous intellectual and technical assistance with qPCR experiments. This work was supported by grants from the Royal Physiographic Society in Lund, the Foundations of Åke Wiberg, Alfred Österlund, Gyllenstierna-Krapperup, Crafoord, Magnus Bergvall, Tornspiran, Clas Groschinsky, Längmanska Kulturfonden, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author Contributions

R.L., H.B. and T.A. conceived and designed the study. K.S.A., H.M. and K.L. collected patient material. K.S.t. and C.B.F.A. generated RoxP producing yeast. G.E.B. and T.A. performed biosensor experiments. T.A. performed biochemistry experiments. A.J. and H.B. performed bioinformatic genelysis. R.L., H.B. and T.A. analyzed the data and drafted the report. All authors read, contributed to, and approved the final interpretation and draft.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-40471-3.

References

- 1.Lood R, Waldetoft KW, Nordenfelt P. Localization-triggered bacterial pathogenesis. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(10):1659–68. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholz CFP, Kilian M. The natural history of cutaneous propionibacteria, and reclassification of selected species within the genus Propionibacterium to the proposed novel genera Acidipropionibacterium gen. nov., Cutibacterium gen. nov. and Pseudopropionibacterium gen. nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2016;66(11):4422–32. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grice EA, et al. Topographical and Temporal Diversity of the Human Skin Microbiome. Science (New York, NY). 2009;324(5931):1190–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agak GW, et al. Propionibacterium acnes Induces an IL-17 Response in Acne Vulgaris that Is Regulated by Vitamin A and Vitamin D. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2014;134(2):366–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmberg A, et al. Biofilm formation by Propionibacterium acnes is a characteristic of invasive isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(8):787–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achermann Y, et al. Characteristics and outcome of 16 periprosthetic shoulder joint infections. Infection. 2013;41(3):613–20. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conen A, et al. Characteristics and treatment outcome of cerebrospinal fluid shunt-associated infections in adults: a retrospective analysis over an 11-year period. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(1):73–82. doi: 10.1086/588298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieger UM, et al. Bacterial biofilms and capsular contracture in patients with breast implants. British Journal of Surgery. 2013;100(6):768–74. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Z, Tseng CH, Strober BE, Pei Z, Blaser MJ. Substantial Alterations of the Cutaneous Bacterial Biota in Psoriatic Lesions. Plos One. 2008;3(7):e2719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drago L, et al. Skin microbiota of first cousins affected by psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Clinical and Molecular. Allergy. 2016;14(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12948-016-0038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cogen AL, Nizet V, Gallo RL. Skin microbiota: a source of disease or defence? The British journal of dermatology. 2008;158(3):442–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allhorn M, Arve S, Bruggemann H, Lood R. A novel enzyme with antioxidant capacity produced by the ubiquitous skin colonizer Propionibacterium acnes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36412. doi: 10.1038/srep36412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu, H.-P. et al. Spatial heterogeneity of gut microbiota reveals multiple bacterial communities with distinct characteristics. 4, 6185 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Grice EA. The skin microbiome: potential for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to cutaneous disease. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2014;33(2):98–103. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakobsson HE, et al. Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by caesarean section. Gut. 2014;63(4):559–66. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YE, Fischbach MA, Belkaid Y. Skin microbiota-host interactions. Nature. 2018;553(7689):427–36. doi: 10.1038/nature25177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen M-T, et al. Lipid moieties on lipoproteins of commensal and non-commensal staphylococci induce differential immune responses. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):2246. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi Y, et al. Association of Intestinal Microbiota with Metabolic Markers and Dietary Habits in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Digestion. 2016;94(2):66–72. doi: 10.1159/000447690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitz-Gibbon S, et al. Propionibacterium acnes strain populations in the human skin microbiome associated with acne. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2013;133(9):2152–60. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kullander J, Forslund O, Dillner J. Staphylococcus aureus and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(2):472–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen RL, Scholz CF, Jensen A, Bruggemann H, Lomholt HB. Propionibacterium Acnes Phylogenetic Type III is Associated with Progressive Macular Hypomelanosis. European journal of microbiology & immunology. 2017;7(1):37–45. doi: 10.1556/1886.2016.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidsson S, et al. Prevalence of Flp Pili-Encoding Plasmids in Cutibacterium acnes Isolates Obtained from Prostatic Tissue. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:2241. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDowell A, Nagy I, Magyari M, Barnard E, Patrick S. The opportunistic pathogen Propionibacterium acnes: insights into typing, human disease, clonal diversification and CAMP factor evolution. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e70897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JL, Cummins CS. Cell Wall Composition and Deoxyribonucleic Acid Similarities Among the Anaerobic Coryneforms, Classical Propionibacteria, and Strains of Arachnia propionica. Journal of Bacteriology. 1972;109(3):1047–66. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.3.1047-1066.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDowell A, et al. Propionibacterium acnes types I and II represent phylogenetically distinct groups. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(1):326–34. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.326-334.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDowell A, Perry AL, Lambert PA, Patrick S. A new phylogenetic group of Propionibacterium acnes. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2008;57(2):218–24. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scholz CFP, Jensen A, Lomholt HB, Brüggemann H, Kilian M. A Novel High-Resolution Single Locus Sequence Typing Scheme for Mixed Populations of Propionibacterium acnes In Vivo. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(8):e104199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lodes MJ, et al. Variable expression of immunoreactive surface proteins of Propionibacterium acnes. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 12):3667–81. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valanne S, et al. CAMP factor homologues in Propionibacterium acnes: a new protein family differentially expressed by types I and II. Microbiology. 2005;151(Pt 5):1369–79. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27788-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagy I, et al. Propionibacterium acnes and lipopolysaccharide induce the expression of antimicrobial peptides and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in human sebocytes. Microbes and Infection. 2006;8(8):2195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lomholt HB, Kilian M. Population Genetic Analysis of Propionibacterium acnes Identifies a Subpopulation and Epidemic Clones Associated with Acne. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu H, et al. Antioxidants and phase 2 enzymes in macrophages: regulation by Nrf2 signaling and protection against oxidative and electrophilic stress. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2008;233(4):463–74. doi: 10.3181/0711-RM-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadam DP, Suryakar AN, Ankush RD, Kadam CY, Deshpande KH. Role of Oxidative Stress in Various Stages of Psoriasis. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2010;25(4):388–92. doi: 10.1007/s12291-010-0043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berman B, Cockerell CJ. Pathobiology of actinic keratosis: Ultraviolet-dependent keratinocyte proliferation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;68(1, Supplement 1):S10–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pulverer G, Ko HL. Fermentative and serological studies on Propionibacterium acnes. Applied microbiology. 1973;25(2):222–9. doi: 10.1128/am.25.2.222-229.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tally FP, Goldin BR, Jacobus NV, Gorbach SL. Superoxide dismutase in anaerobic bacteria of clinical significance. Infection and Immunity. 1977;16(1):20–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.16.1.20-25.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holland C, et al. Proteomic identification of secreted proteins of Propionibacterium acnes. BMC Microbiology. 2010;10:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narendhirakannan RT, Hannah MA. Oxidative stress and skin cancer: an overview. Indian journal of clinical biochemistry: IJCB. 2013;28(2):110–5. doi: 10.1007/s12291-012-0278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erturk G, Bereli N, Tumer MA, Say R, Denizli A. Molecularly imprinted cryogels for human interferon-alpha purification from human gingival fibroblast culture. J Mol Recognit. 2013;26(12):633–42. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Re R, et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(9–10):1231–7. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ertürk, G., Hedström, M., Mattiasson, B., Ruzgas, T. & Lood, R. Highly sensitive detection and quantification of the secreted bacterial benevolence factor RoxP using a capacitive biosensor: A possible early detection system for oxidative skin diseases e0193754 p (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2013;79(17):5112–20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huse SM, Welch DM, Morrison HG, Sogin ML. Ironing out the wrinkles in the rare biosphere through improved OTU clustering. Environmental microbiology. 2010;12(7):1889–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2011;27(16):2194–200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, T. et al. The Human Oral Microbiome Database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database: the journal of biological databases and curation. 2010, baq013 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Segata N, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biology. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nazipi, S., Stodkilde-Jorgensen, K., Scavenius, C. & Bruggemann, H. The Skin Bacterium Propionibacterium acnes Employs Two Variants of Hyaluronate Lyase with Distinct Properties. Microorganisms5(3) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Kopp, C. et al. 23Na magnetic resonance imaging-determined tissue sodium in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients. Hypertension61(3), 635 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Li Z, Zheng J, Zhang X-F. Detrimental Effects of Paraquat on Astrocytes-Regulating Synaptic Functions. Dose-response: a publication of International HormesisSociety. 2018;16(2):1559325818761681-. doi: 10.1177/1559325818761681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen AC, Halliday GM, Damian DL. Non-melanoma skin cancer: carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Pathology. 2013;45(3):331–41. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32835f515c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sander CS, Hamm F, Elsner P, Thiele JJ. Oxidative stress in malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. The British journal of dermatology. 2003;148(5):913–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y-J, et al. Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16(4):7493. doi: 10.3390/ijms16047493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, et al. Antioxidant Properties of Probiotic Bacteria. Nutrients. 2017;9(5):521. doi: 10.3390/nu9050521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis in the human skin microbiome mediates fermentation to inhibit the growth of Propionibacterium acnes: implications of probiotics in acne vulgaris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(1):411–24. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5394-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shu M, et al. Fermentation of Propionibacterium acnes, a commensal bacterium in the human skin microbiome, as skin probiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chenchin EE, Yamamoto HY. Distribution And Heat Inactivation Of Peroxidase Isoenzymes In Sweet Corn. Journal of Food Science. 1973;38(1):40–2. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis DA, Hengeltraub SF, Gao FC, Leivant MA, Spandau DF. Aberrant NF-κB Activity in HaCaT Cells Alters their Response to UVB Signaling. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2006;126(8):1885–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schreck R, Rieber P, Baeuerle PA. Reactive oxygen intermediates as apparently widely used messengers in the activation of the NF-kappa B transcription factor and HIV-1. The EMBO journal. 1991;10(8):2247–58. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inui M, et al. Mechanisms of inhibitory effects of CoQ10 on UVB-induced wrinkle formation in vitro and in vivo. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 2008;32(1–4):237–43. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hofbauer G, et al. Swiss clinical practice guidelines on field cancerization of the skin. Swiss medical weekly. 2014;144:w14026. doi: 10.4414/smw.2014.14026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hawk MA, McCallister C, Schafer ZT. Antioxidant Activity during Tumor Progression: A Necessity for the Survival of Cancer Cells? Cancers. 2016;8(10):92. doi: 10.3390/cancers8100092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.