Abstract

Manipulating topological spin textures is a key for exploring unprecedented emergent electromagnetic phenomena. Whereas switching control of magnetic skyrmions, e.g., the transitions between a skyrmion-lattice phase and conventional magnetic orders, is intensively studied towards development of future memory device concepts, transitions among spin textures with different topological orders remain largely unexplored. Here we develop a series of chiral magnets MnSi1−xGex, serving as a platform for transitions among skyrmion- and hedgehog-lattice states. By neutron scattering, Lorentz transmission electron microscopy and high-field transport measurements, we observe three different topological spin textures with variation of the lattice constant controlled by Si/Ge substitution: two-dimensional skyrmion lattice in x = 0–0.25 and two distinct three-dimensional hedgehog lattices in x = 0.3–0.6 and x = 0.7–1. The emergence of various topological spin states in the chemical-pressure-controlled materials suggests a new route for direct manipulation of the spin-texture topology by facile mechanical methods.

Manipulating topological spin textures are demanded for future spintronic devices, but knowledge about phase transitions among different spin textures remain limited. Here, Fujishiro and Kanazawa et al. report chemical-pressure-controlled phase transitions between different topological spin textures in chiral magnets MnSi1−xGex.

Introduction

The concept of topology provides a powerful scheme for the classification of electronic and magnetic states, and also for the description of their physical properties1. Topology of a magnetic structure is characterized by the winding number . This quantity counts how many times the direction of the local magnetization, i.e., n(r) = m(r)/|m(r)|, wraps the unit sphere within the unit area S. When a magnetic structure possesses a non-zero integer winding number, it behaves as a topologically stable spin-object, producing emergent phenomena unique to its topological class.

A representative example is the magnetic skyrmion, which is a two-dimensional (2D) nanometric vortex-like structure consisting of many electron spins2–4. In the bulky compounds, skyrmions elongate in cylindrical forms, usually assembling in a hexagonal lattice, i.e., the skyrmion lattice (SkL). In reciprocal space, the hexagonal SkL can be approximately described as a superposition of three helical modulations with the wavevectors (q-vectors) forming a mutual angle of 120° in a plane perpendicular to external magnetic field H, as shown in Fig. 1a. Skyrmion-hosting materials are of great variety, including non-centrosymmetric bulk magnets5 and multilayered thin films6,7. Through the interaction with conduction electrons, skyrmions generate the effective magnetic field confined in each interior, so-called emergent magnetic field as defined by the Berry curvature . Owing to their topology, skyrmions carry the quantized emergent flux in case of the strong spin-charge coupling, which offers attractive spintronic functionalities conserved even in nano-scale devices;8–10 such as topological Hall effects11–13 and emergent electromagnetic inductions1,14–16.

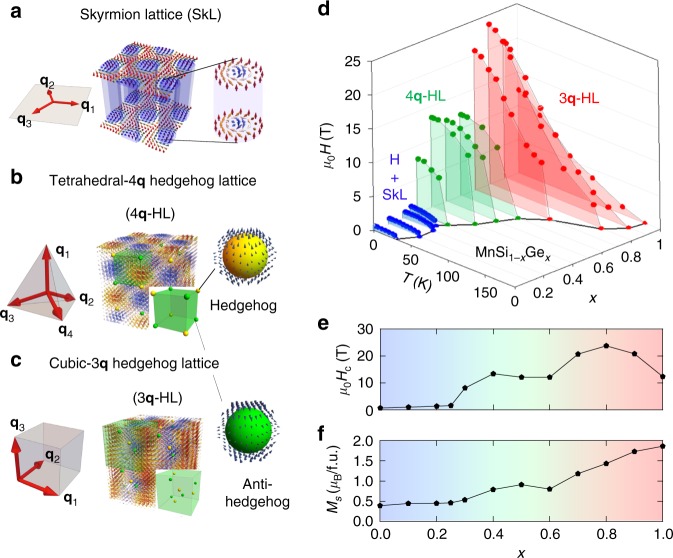

Fig. 1.

Schematics of topological multiple-q spin textures and two-step magnetic transitions in MnSi1−xGex. a Spin configurations of two-dimensional skyrmion lattice (2D SkL), which is a hexagonal array of skyrmion cylinders. It is characterized by three helical modulation vectors perpendicular to external magnetic field H. b Spin configurations of tetrahedral-4q hedgehog lattice (4q-HL), which is described by four q-vectors pointing in the apical directions of a regular tetrahedron. Those q-vectors are fixed along 〈111〉 crystal axes at zero H. Hedgehogs and anti-hedgehogs are at face-centered-cubic positions as illustrated in the bottom right green box representing the magnetic unit cell. c Spin configurations of cubic-3q hedgehog lattice (3q-HL), which is described by three orthogonal q-vectors, which are pinned along 〈100〉 crystal axes at zero H. In a–c the red (blue) arrows drawn in each spin texture represent up (down) magnetic moments. d Variation of phase boundary between ferromagnetic and helimagnetically ordered states as a function of magnetic field H, temperature T, and x in MnSi1−xGex. Red, green, and blue color denote 3q-HL, 4q-HL, and helical(H)/SkL states, respectively. The variation of magnetic transition temperature is indicated by the black line on the bottom plane. (See also Supplementary Fig. 2) e, f Composition x dependence of ferromagnetic transition field Hc (e) and saturation magnetization Ms (f)

Also as a result of the geometric constraint, transitions of topological spin textures are accompanied by dynamics of topological spin defects, as exemplified by the emergence of spin hedgehogs in the course of creation or annihilation of skyrmions17,18. Because transformations between skyrmions and conventional magnetic orders need discrete changes in the winding number, they cannot be realized by smooth change of the directions of local spins. Instead, it is necessary to introduce hedgehog point defects, which are three-dimensional (3D) topological spin structures, behaving as emergent magnetic monopoles or anti-monopoles with non-zero divergence of emergent magnetic field 19. The motions of hedgehogs locally give or remove the topological winding number, causing the topological transition through the elongation, contraction, coalescence, and division of skyrmion strings17,18. In association with such dynamics of topological charges, the topological transition of a spin texture often involves non-trivial emergent phenomena, e.g., the formation of fluctuating topological magnetic order20, the concomitant non-Fermi-liquid like behavior21 and electrical magnetochiral effect22. Spin hedgehogs are also found as a dense lattice form in MnGe, namely the array of hedgehogs and anti-hedgehogs connected by skyrmion strings. This state can be described approximately by three helical modulations with their q-vectors forming the orthogonal sides of a cube23 and is here referred to as cubic-3q hedgehog lattice (HL) (Fig. 1c). The transition from the HL state to the non-topological state, e.g., single-q conical and ferromangnetic state, undergoes the pair annihilation of hedgehogs and anti-hedgehogs24, which entails critical anomalies of resistivity, elastic property, and thermopower as well24,25.

In order to harness the topological properties unique to each spin texture and to explore non-trivial emergent phenomena at their transitions, direct control of topology of spin texture is essential. In this context, switching of the spin textures among plural different topologically nontrivial classes has remained a challenge. We focus on chemical/mechanical pressure as one potential approach to this end, by achieving dramatic modification in magnetic interactions through changing inter-atomic distances.

Here we report on the topological transitions among 2D SkL and 3D HLs in cubic chiral magnets MnSi1−xGex. By changing chemical pressure through substitution between Si and Ge, in other words, by controlling the lattice constant a (Supplementary Fig. 1), we observed that the SkL in MnSi undergoes two-step transitions to the cubic-3q HL in MnGe. In the intermediate composition range, we unveiled a new topological spin texture characterized by four q-vectors pointing in the apical directions of a regular tetrahedron. This state corresponds to the face-centered-cubic array of the hedgehogs and anti-hedgehogs, which we call tetrahedral-4q HL (Fig. 1b). Our neutron scattering experiment and Lorentz transmission electron microscopy (LTEM) observation confirm the conventional SkL for Si-rich composition range (x = 0–0.25), tetrahedral-4q HL for the intermediate range (x = 0.3–0.6), and cubic-3q HL for Ge-rich range (x = 0.7–1). Furthermore, by high-field Hall resistivity measurements, we identified topological Hall effect of Berry-phase origin in each magnetic phase, supporting their topological spin arrangements.

Results

Overview of topological magnetic transitions in MnSi1−xGex

To overview the magnetic transitions in MnSi1−xGex, we first show the magnetic phase diagrams for varying x as summarized in Fig. 1d. (See Supplementary Fig. 2 for magnetic transition temperatures TN for varying x in detail.) The drawn phase boundary line for each x represent the ferromagnetic transition, determined from magnetization measurements. (See Supplementary Fig. 3 for details.) The variation in the phase diagram indicates that MnSi1−xGex can be sorted into three categories, as evident from the distinct value of ferromagnetic-transition magnetic field (Hc) at the lowest temperature; two steep changes in Hc at x ~ 0.3 and x ~ 0.7 (ΔHc ~ 10 T) suggests the magnetic-structure transitions (Fig. 1e). There are also recognized characteristic profiles in x-dependence of other magnetic properties. As for the saturation magnetization (Ms), a plateau-like structure appears around Ms ~ 1 μB/f.u. within the range x = 0.4–0.6 (Fig. 1f). Incidentally, the similar feature was observed in a former study on hydrostatic-pressure dependence of Ms in MnGe26.

SANS and LTEM studies at zero magnetic field

In order to clarify the variation of magnetic period (λ) and direction of wavevectors (q-vectors) in MnSi1−xGex, small- and wide-angle neutron scattering experiments as well as LTEM observations were performed at zero magnetic field. Figure 2a–c show the SANS intensity patterns of x = 0.2, 0.6, and 0.8 after zero field cooling from room temperature. The observed Debye-ring-like patterns indicate the formation of periodically modulated magnetic structures. Their modulation periods are determined from the radius (q) of the each diffracted ring pattern as λ = 2π/q (Fig. 2h).

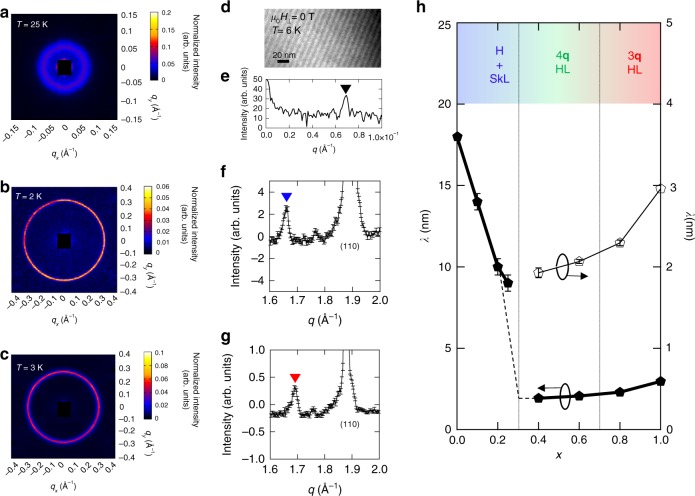

Fig. 2.

Magnetic modulation periods and directions in MnSi1−xGex at zero magnetic field. a–c The small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) intensity patterns of x = 0.2 (T = 25 K) (a), x = 0.6 (T = 2 K) (b), and x = 0.8 (T = 3 K) (c) after zero field cooling. d Lorentz transmission electron microscopy (LTEM) image in (001) crystal plane for x = 0.2 (T = 6 K), where the helical structure with its q-vector running in one of 〈100〉 directions is observed. e Fourier transform profile of the LTEM image shown in d, with the black triangle representing the peak position (|q| ~ 0.069 Å−1). f, g Powder neutron diffraction patterns around the (110) nuclear reflection of x = 0.6 (T = 2 K) (f) and x = 0.8 (T = 3 K) (g). Background signals measured at high temperatures are subtracted. Each satellite peak, which is indicated by blue or red triangle, is assigned to the formation of magnetic structure modulating along 〈111〉 (f) or 〈100〉 directions (g), respectively. The error bars represent statistical error of one standard deviation. h Variation of magnetic modulation period (λ) as a function of composition x at the lowest temperature (solid markers and lines), which are revealed by LTEM observation (x = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.25) and SANS measurement (x ≥ 0.4). The open markers for the right axis show the magnified data of x ≥ 0.4. The dashed lines show the guide to the eyes for the extrapolated variation of magnetic period in 0.2 ≤ x ≤ 0.4. The data of MnSi and MnGe are cited from refs. 3,13, respectively. The error bars for x ≤ 0.25 are defined by the spatial resolution of Lorentz transmission electron microscope, while those for x ≥ 0.4 represent statistical error of one standard deviation of the SANS measurements

The q-vectors, which are fixed along specific crystal-axes due to magnetic anisotropy, were identified by using LTEM for x = 0.2 (Fig. 2d, e) and by wide-angle neutron scattering for x = 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 (Fig. 2f, g). (See also Supplementary Fig. 6 for all the data sets.) In a thin plate sample of x = 0.2, there observed a helical structure with q || 〈100〉 and λ = 9 nm (Fig. 2e). Here we note that the observed q-direction is not necessarily the same in bulk samples as seen in the LTEM study on MnSi, where the helical direction is dependent on the crystalline orientation due to large magnetic anisotropy effects at the surfaces27. Since the q-directions in bulks of MnSi and x = 0.4 (Supplementary Fig. 6b) are both parallel to 〈111〉, we speculate that it is also the same in the x = 0.2 bulk sample, although the direct verification by wide-angle neutron scattering is difficult within the current q-resolution. (See Supplementary Fig. 6a). In powder samples of x = 0.6 and 0.8, we show the wide-angle neutron diffraction profiles around (110) nuclear reflection in Fig. 2f, g. Because magnetic reflections generally appear as satellite peaks at the wavenumber of in a powder neutron diffraction, we can determine the q-direction from the satellite peak position once we identify the magnitude of q by SANS13. Here qn is the reciprocal lattice vector. Each satellite peak observed in x = 0.6 and 0.8 (indicated by blue and red triangles in Fig. 2f, g) can be indexed as and , respectively. Namely, the q-vector directions are along 〈111〉 crystal axes for x = 0.6, and 〈100〉 crystal axes for x = 0.8.

As summarized in Fig. 2h, there are two features in x-dependence of the magnetic modulation q; the two-step magnetic transitions observed as distinct changes in the phase diagram (Fig. 1d). One is the discontinuous variation in λ (=2π/q) at x ~ 0.3 and the other is change in the pinned q-direction at x ~ 0.7. It is therefore clear that three distinct magnetic phases are realized in MnSi1−xGex. In later sections, those respectively turn out to be helicl/SkL (x = 0–0.25), tetrahedral-4q HL (x = 0.3–0.6), and cubic-3q HL (x = 0.7–1).

Formation mechanisms of shortperiod topological spin textures

It is noteworthy that such remarkable variations in the magnetic properties can be driven essentially by such a lattice-constant change without any change in lattice symmetry. Here we discuss the origin of the dramatic magnetic transitions in MnSi1−xGex. One important indication we obtain is that the dominant magnetic interactions for the 3D HL states may differ from those for 2D SkL where the competition between ferromagnetic exchange interaction (EXI) and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI) determines the basic magnetic properties28, such as (a being the lattice constant) and . In the conventional SkL materials, the magnetic ground state is a long-period helical structure (λ typically ranges from 10 to 100 nm) with relatively small (<1 T) since the energy scale is well-separated as . If the same model could be applied, the extremely short (1.94–2.80 nm) and large (12–24 T) observed in MnSi1−xGex (x = 0.4–1) would require much larger DMI even exceeding EXI. The band structure calculations29, however, demonstrate a contradictory behavior of DMI in MnSi1−xGex to this naive expectation: DMI gets rather smaller with increasing x, whereas the calculated values of Ms are in accord with the observed ones (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, the DMI may not be the primary origin of the short-period helical structure in 3D HL. Instead, the magnetic frustration or Ruderman-Kittel-Kasuya-Yosida (RKKY) interaction30–33 causing competing ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic EXIs can be a possible mechanism. Possibly related to such conduction-electron mediated exchange interactions, we found that the strong Hubbard-U implemented in the band structure calculation favors a short-period helical structure (Supplementary Fig. 5). Further theoretical studies are desired to clarify the crucial magnetic interaction, which takes over from DMI in the course of enlarging the lattice constant.

SANS and LTEM studies under magnetic fields

Having confirmed the variation of magnetic properties in MnSi1−xGex, we investigated the magnetic structures under magnetic fields by SANS in x = 0.2, 0.6, and 0.8 (as representative compositions of the three magnetic phases), and by LTEM in the thin plate of x = 0.2. Magnetic field (H) is applied perpendicular to the incident neutron beam for SANS experiment (Fig. 3a), while H is applied parallel to the electron beam for LTEM measurement (Fig. 3b). As for x = 0.2, LTEM directly reveals the formation of a hexagonal SkL in the plane perpendicular to H, which is also confirmed by the six-fold Fourier transform image (Fig. 3c).

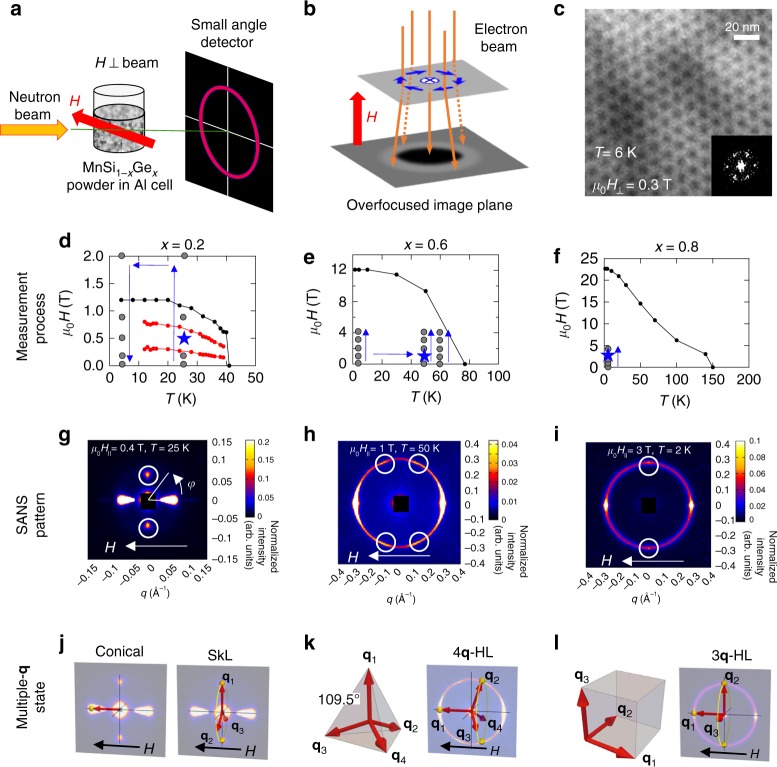

Fig. 3.

Magnetic structures of MnSi1−xGex revealed by small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) and Lorentz transmission electron microscopy (LTEM) under magnetic field. a The SANS setup with magnetic field H perpendicular to the incident neutron beam. b Schematic illustration of LTEM observation with H parallel to the incident electron beam (orange lines), where the blue arrows represent the in-plane magnetic moment configuration of a skyrmion. c The over-focused LTEM image (T = 6 K, μ0H = 0.3 T) in (001) crystal plane and its Fourier transform pattern. d–f The SANS measurement points (gray dots) and sequences (blue arrows) are shown in the magnetic phase diagrams of x = 0.2 (d), x = 0.6 (e), and x = 0.8 (f), where the blue stars represent the data points shown in g–i. The SANS intensity patterns of x = 0.2 (T = 25 K, μ0H = 0.5 T) (g), x = 0.6 (T = 50 K, μ0H = 1 T) (h), and x = 0.8 (T = 2 K, μ0H = 3 T) (i). The small white circles emphasize the characteristic peak intensities for each composition. The candidate multiple-q structures explaining the observed SANS intensity patterns are shown in h–l, where the yellow rings represent the rotation degrees of freedom of q-vectors due to randomly oriented crystal domains in the polycrystalline samples and the yellow dots represent the scattering intensities on the detector plane

In Fig. 3d–f, we display all the measurement points (gray dots) and sequences (blue arrows) of SANS in the magnetic phase diagrams, and the representative SANS patterns obtained at the T–H points (highlighted by blue stars in Fig. 3d–f) are shown in Fig. 3g–i. (See Supplementary Figs 7–9 for the SANS data at other temperatures and magnetic fields). The SANS pattern on the polycrystalline compound (Fig. 3g) exhibits intensity peaks parallel (, ) and perpendicular () to H, which indicates the conical state modulating along H coexists with SkL. Because only a small portion of SkL states in powder grains can meet the diffraction condition as illustrated in Fig. 3j, the much weaker intensity peaks were observed at than those scattered at , by the conical state. Incidentally, we also confirmed that the peaks at only emerge in the SkL phase identified by the magnetization measurements. (See Supplementary Fig. 7 for details).

In x = 0.6 and 0.8, we also detect characteristic SANS patterns under H: In addition to the intensity peaks at , , there appear peaks at for (Fig. 3h) and at for (Fig. 3i). We interpret these SANS patterns in terms of multiple-q structures. As for x = 0.6, Fig. 4 illustrates the possible multiple-q structure explaining the SANS result, i.e., the tetrahedral-4q state. One of the four q-vectors flips along the H-direction, as is the case of many other B20-type magnets28, and generates scattering intensity at (), while the remaining three q-vectors produce intensities at (Fig. 3k). As for x = 0.8, the observed intensity pattern is essentially identical to that of MnGe where the cubic-3q HL is realized23. In this case, one of the three q-vectors flips along the H-direction (), while the other two orthogonal q-vectors generate scattering intensities at , as illustrated in Fig. 3l. Importantly, these 3q and 4q HL states dominates the whole magnetic-order phase below Hc shown in Fig. 1d, whereas the SkL state in the Si-rich region is generated by variation of H from the nearby helical/conical states (see Supplementary Fig. 7) as commonly observed in the SkL-hosting chiral magnets28.

Fig. 4.

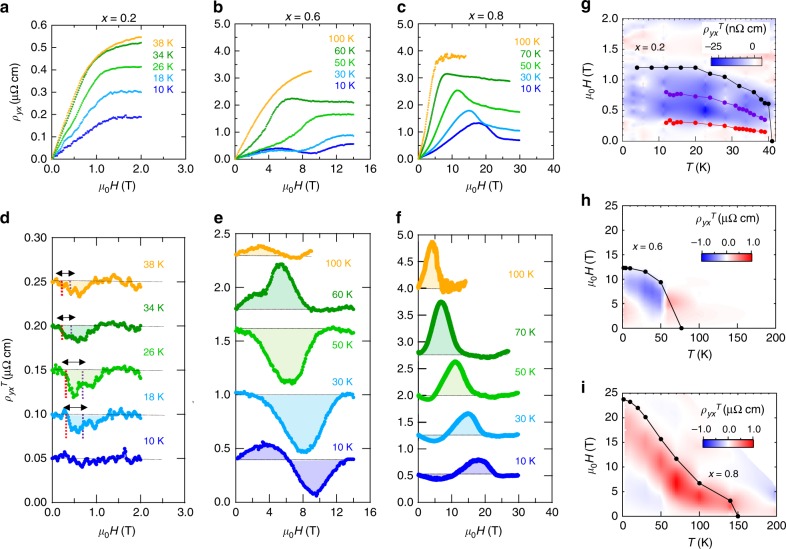

Topological Hall effect in MnSi1−xGex. a–c Hall resistivity measured at various temperatures for x = 0.2 (a), x = 0.6 (b), and x = 0.8 (c). d–f Topological Hall resistivity estimated at various temperatures for x = 0.2 (d), x = 0.6 (e), and x = 0.8 (f). In panel d, the black double-headed arrows represent the H-region of skyrmion phase at each temperature; the red and purple dashed lines represent the lower- and higher-H boundaries, respectively. g–i Color maps of in the magnetic phase diagram for x = 0.2 (g), x = 0.6 (h), and x = 0.8 (i). The black dots and lines represent boundary between ferromagnetic state and helimagnetically ordered state. In panel g, the red and purple lines represent the lower- and higher-H boundaries for the skyrmion phase in x = 0.2. (See Supplementary Fig. 7)

Here we note that we cannot exclude a possibility of multi-domain state of the single-q helical structure on the basis of the SANS results alone. As demonstrated in the following section, however, such a scenario is incompatible with the observed large topological Hall effect, which is the hallmark of the formation of non-coplanar spin textures endowed with scalar spin chirality.

High-magnetic-field measurements of topological Hall effect

Outcomes of these topological spin arrangements show up in the large topological Hall responses arising from their scalar spin chirality or skyrmion number34. The measured Hall resistivity for are summarized in Fig. 4a–c. We estimate the contributions from normal () and anomalous () Hall effects35 by reproducing in the ferromagnetic (field-induced spin collinear) region with use of the fitting curve , where and are the normal and anomalous Hall coefficients, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for and Supplementary Fig. 10 for ). Topological Hall effect (THE) arises as the deviation from the conventional contributions: . In MnSi1−xGex (x = 0.2) hosting the SkL state, overall H-dependence of obeys that of M (Supplementary Fig. 3), that suggests the dominant contribution from the conventional anomalous Hall effect (Fig. 4a). Besides, we identified negative in the intermediate H-region below Hc above 12 K (Fig. 4d). As seen in the color map of in Fig. 4g, reaches its maximum magnitude of near the center of SkL phase; and finite persists even in the conical phase, i.e., in the H-region between SkL and ferromagnetic states, implying that a part of skyrmions remain to subsist perhaps as disordered aggregation4.

In contrast, in MnSi1−xGex (x = 0.6 and 0.8) with HL states clearly indicate the large deviation from the conventional M-proportional profile, as shown in Fig. 4b, c. The estimated shows complex behaviors with sign changes against T and H variations, as well as one-order-of-magnitude larger values than that in x = 0.2 (Fig. 4e, f, h, i.). The observed THE not only corroborate the formation of the topological multiple-q spin textures, but also exhibit different behaviors between tetrahedral-4q HL and cubic-3q HL. To be specific, MnSi1−xGex with cubic-3q HL (x = 0.7–0.9 and MnGe13) share similarity in sign change of : negative in the low-T and low-H region gives way to positive in the high-T and high-H region (Fig. 4f, i and Supplementary Fig. 11). The negative and positive may be attributed to static and fluctuating effects of emergent magnetic field13,24,36. As for x = 0.6 compound with tetrahedral-4q HL, the magnitude of is gigantic as well, while its T- and H-dependences are complicated to interpret (Fig. 4h). We note that such complex -profiles with sign changes are also reported at the transitions between versatile topological spin structures, including 4q-HL, in SrFeO337,38. By analogy with it, the sign change of at low temperatures in x = 0.6 (e.g., T = 10 K in Fig. 4e) may indicate a transition into different multiple-q states or the field-induced modification of the 4q structure, which remains an open question. We also note that there may exist robust or pinned excitations of spin hedgehogs even in the nominally ferromagnetic region25, which may imperil the validity of the present estimation of topological Hall effect. Hence, the magnitude and the sign changes of topological Hall resistivity may be difficult to quantitatively elucidate at the moment, while the presence of non-coplanar spin texture manifests itself by such anomalously large signals of topological Hall resistivity.

Discussion

The present results not only on the SANS and LTEM but also on the topological Hall effects unveil the transitions among distinct topological spin textures, namely 2D SkL and two classes of 3D HLs in cubic chiral magnets MnSi1−xGex. Compared with the case of SrFeO3 where magnetic domains with different helicity and vorticity degrees of freedom should coexist due to the centrosymmetric crystal structure38, a point of uniqueness in MnSi1−xGex is ascribed to the fixed helicity and vorticity over the whole chiral lattice. In addition, the transitions between different topological spin textures can be realized simply by controlling lattice constant; therefore, it would be possible to switch the topology of spin textures by application of small pressure or strain, once a composition x is tuned to the transition points (x ~ 0.3 and 0.7). Given that pressure is a fundamental variable that controls the properties of materials by changing inter-atomic distance or electron transfer interaction39, the impact of pressure on topological spin textures deserves further investigations in a wide range of materials in the light of the exploration of novel spin textures and emergent electrodynamics.

Methods

Sample preparation

Polycrystalline samples of MnSi1−xGex were prepared by the high-pressure synthesis technique. Mn, Si, and Ge were first mixed with stoichiometric ratio and then melted in an arc furnace under an argon atmosphere. Afterwards, it was heated at 1073 K for 1 h under 5.5–6.0 GPa with a cubic-anvil-type high-pressure apparatus. Powder x-ray analyses confirmed B20-type crystal structure (P213).

Magnetic and transport property measurements

Magnetization was measured either by using ACMS option with Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) or by DC option with Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS). Magneto-resistivity and Hall-resistivity up to 14 T were measured by using AC-transport option with PPMS. Magnetic field was applied perpendicular to electrical current. Higher-field measurements of magnetization and Hall resistivity were performed utilizing non-destructive pulse magnets energized by capacitor banks and a flywheel DC generator installed at International MegaGauss Science Laboratory of Institute for Solid State Physics (ISSP), University of Tokyo, Japan, respectively. The high-field magnetization was measured up to 56 T by the conventional induction method, using coaxial pickup coils. The high-field resistivity was measured up to 30T using the long (~1s) field pulse with the AC four-wires method employing a numerical phase detection technique with a sampling rate of 200,000 data points per second and an excitation current of 10 kHz and 200 mAp-p.

Lorentz TEM observations

Lorentz TEM observations for a (001) MnSi0.8Ge0.2 thin plate were performed using a multifunctional transmission electron microscope (JEM2800, JEOL) equipped with double-tilt helium cooling holder (Gatan ULTDT). The thin plate was prepared by an Ar+ milling process after mechanical polishing of the bulk sample.

Neutron scattering

Neutron scattering experiments were performed at small- and wide-angle neutron scattering instrument (TAIKAN) built at BL15 of Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility (MLF) in Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (J-PARC)40. A powder sample of MnSi1−xGex was packed in an aluminum container filled by He gas, and installed in a cryomagnet. The weight of the powder sample was , , , and . Magnetic field was applied perpendicular to the incident neutron beam. The diffracted neutron beam with the wavelength of Å was collected by four detector banks of small-, middle-, and high-angle and backward detector banks, and analysed by using time-of-flight (TOF) method.

Band structure calculations

Electronic structure calculations were performed using the plane-wave basis set with the projector augmented wave (PAW) scheme41 as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)42,43. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional44 and a cutoff energy of 500 eV were used. Experimental crystal structures45,46 were adopted and the lattice constants were changed by fixing the fractional coordinates of the atoms. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions were evaluated using a spin current formalism29,47. To calculate the energy of the spiral spin structures, a generalized Bloch theorem was employed48. The effect of strong correlation was discussed using the DFT + U method49.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Taguchi and A. Kitaori for fruitful discussions. The neutron experiment at the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility of J-PARC was performed under the user program (Proposal No. 2017L0701 and No. 2016C0002). This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grants No. 24224009 and No. 18K13497, and No. 17H02815) and JST CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR16F1 and JPMJCR1874).

Author contributions

Y.F. synthesized polycrystalline samples of MnSi1−xGex and performed magnetization and transport measurement by using PPMS/MPMS. Neutron scattering experiment were performed by Y.F., N.K., and T.N. with the support from K.O., Y.K., K.Ka., and T.A. LTEM observation was done by X.Z.Y. Magnetization and Hall resistivity measurement under high magnetic field was performed by Y.F., N.K., H.M., A.M., K.A., and A.M. under the supervision of M.T. and K.Ki. Band structure calculations were performed by T.K. and R.A.; Y.F. and N.K. wrote the draft with the support from Y.T. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Y.T. conceived and organized the project.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Y. Fujishiro, Email: fujishiro@cmr.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp

N. Kanazawa, Email: kanazawa@ap.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-08985-6.

References

- 1.Mermin ND. The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1979;51:591–648. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.51.591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogdanov N, Yablonskii DA. Thermodynamically stable “vortices” in magnetically ordered crystals: the mixed state of magnets. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 1989;68:101–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mühlbauer S, et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science. 2009;323:915–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1166767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu XZ, et al. Real space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature. 2010;465:901–904. doi: 10.1038/nature09124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanazawa N, Seki S, Tokura Y. Noncentrosymmetric magnets hosting magnetic skyrmions. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1603227. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesendanger R. Nanoscale magnetic skyrmions in metallic films and multilayers: a new twist for spintronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:16044. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fert A, Reyren N, Cros V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:17031. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romming N, et al. Writing and deleting single magnetic skyrmions. Science. 2013;341:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1240573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki J, Mochizuki M, Nagaosa N. Current-induced skyrmion dynamics in constricted geometries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:742–747. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampaio J, et al. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:839–844. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M, et al. Unusual hall effect anomaly in MnSi under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:186601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.186601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neubauer A, et al. Topological hall effect in the a phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:186602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.186602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanazawa N, et al. Large topological hall effect in a short-period helimagnet MnGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;106:156603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.156603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zang JD, Mostovoy M, Han JH, Nagaosa N. Dynamics of skyrmion crystals in metallic thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107:136804. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.136804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everschor K, Garst M, Duine RA, Rosch A. Current-induced rotational torques in the skymion lattice phase of chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:064401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.064401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz T, et al. Emergent electrodynamics of skyrmions in a chiral magnet. Nat. Phys. 2012;8:301–304. doi: 10.1038/nphys2231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milde P, et al. Unwinding of a skyrmion lattice by magnetic monopoles. Science. 2013;340:1076–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1234657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schütte C, Rosch A. Dynamics and energetics of emergent magnetic monopoles in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;90:174432. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.174432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volovik GE. Linear momentum in ferromagnets. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1987;20:L83–L87. doi: 10.1088/0022-3719/20/7/003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfleiderer C, et al. Partial order in the non-Fermi-liquid phase of MnSi. Nature. 2004;427:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature02232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritz R, et al. Formation of a topological non-Fermi liquid in MnSi. Nature. 2013;497:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokouchi T, et al. Electrical magnetochiral effect induced by chiral spin fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:866. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01094-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanazawa N, et al. Possible skyrmion-lattice ground state in B20 chiral-lattice magnet MnGe as seen via small-angle neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;86:134425. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.134425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanazawa N, et al. Critical phenomena of emergent magnetic monopoles in a chiral magnet. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11622. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujishiro Y, et al. Large magneto-thermopower in MnGe with topological spin texture. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:408. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutsch M, et al. Two-step pressure-induced collapse of magnetic order in the MnGe chiral magnet. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:180407(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.180407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu XZ, et al. Variation of skyrmion forms and their stability in MnSi thin plates. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;91:054411. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.91.054411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer, A. & Pfleiderer, C. Generic aspects of skyrmion lattices in chiral magnets. Springer Series in Materials Science. 228, p. 1–28 (Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2016).

- 29.Koretsune T, Kikuchi T, Arita R. First-principles evaluation of the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018;87:041011. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.87.041011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altynbaev E, et al. Hidden quantum phase transition in Mn1−xFexGe evidenced by small-angle neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;94:174403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.174403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayami S, Ozawa R, Motome Y. Effective bilinear-biquadratic model for noncoplanar ordering in itinerant magnets. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:224424. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.224424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okubo T, Chung S, Kawamura H. Multiple-q states and the skyrmion lattice of the triangular-lattice Heisenberg antiferromagnet under magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:017206. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.017206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leonov AO, Mostovoy M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8275. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagaosa N, Tokura Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:899–911. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaosa N, et al. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010;82:1539–1592. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.1539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishizuka H, Nagaosa N. Spin chirality induced skew scattering and anomalous Hall effect in chiral magnets. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaap9962. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aap9962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishiwata S, et al. Versatile helimagnetic phases under magnetic fields in cubic perovskite SrFeO3. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:054427. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.054427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishiwata, S. et al. Emergent topological spin structures in a centrosymmetric cubic perovskite. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.02309 (2018).

- 39.Zhang L, et al. Materials discovery at high pressures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:17005. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takata S, et al. The design and q resolution of the small and wide angle neutron scattering instrument (TAIKAN) in J-PARC. JPS Conf. Proc. 2015;8:03620. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blöchl PE. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:17953–17979. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kresse G, Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1758–1775. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hobbs D, Kresse G, Hafner J. Fully unconstrained noncollinear magnetism within the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 2000;62:11556. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.62.11556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grigoriev SV, et al. Interplay between crystalline chirality and magnetic structure in Mn1−xFexSi. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;81:012408. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.012408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyadkin V, et al. Crystal structure and thermal expansion of Mn1−xFexGe. Acta Cryst. B. 2014;70:676. doi: 10.1107/S2052520614006611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kikuchi T, Koretsune T, Arita R, Tatara G. Dzyaloshinskii-moriya interaction as a consequence of a doppler shift due to spin-orbit-induced intrinsic spin current. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;116:247201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.247201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandratskii LM. Energy band structure calculations for crystals with spiral magnetic structure. Phys. Status Solidi B. 1986;136:167. doi: 10.1002/pssb.2221360119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liechtenstein AI, Anisimov VI, Zaanen J. Density-functional theory and strong interactions: orbital ordering in Mott-Hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B. 1995;52:R5467. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.52.R5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.