Abstract

Human myogenic precursor cells have been isolated and expanded from a number of skeletal muscles, but alternative donor biopsy sites must be sought after in diseases where muscle damage is widespread. Biopsy sites must be relatively accessible, and the biopsied muscle dispensable. Here, we aimed to histologically characterize the cremaster muscle with regard number of satellite cells and regenerative fibres, and to isolate and characterize human cremaster muscle-derived stem/precursor cells in adult male donors with the objective of characterizing this muscle as a novel source of myogenic precursor cells. Cremaster muscle biopsies (or adjacent non-muscle tissue for negative controls; N = 19) were taken from male patients undergoing routine surgery for urogenital pathology. Myosphere cultures were derived and tested for their in vitro and in vivo myogenic differentiation and muscle regeneration capacities. Cremaster-derived myogenic precursor cells were maintained by myosphere culture and efficiently differentiated to myotubes in adhesion culture. Upon transplantation to an immunocompromised mouse model of cardiotoxin-induced acute muscle damage, human cremaster-derived myogenic precursor cells survived to the transplants and contributed to muscle regeneration. These precursors are a good candidate for cell therapy approaches of skeletal muscle. Due to their location and developmental origin, we propose that they might be best suited for regeneration of the rhabdosphincter in patients undergoing stress urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy.

Introduction

In striated muscle, adult myogenic stem cells are known as satellite cells, due to their superficial position on muscle fibres1. The myogenic process is a multifaceted transition between precursor states (quiescence, activation, proliferation and differentiation) that precede fusion of the myoblasts to regenerative muscle fibres2. Besides, satellite cells reside in a complex niche, which includes other precursors such as fibro-adipogenic precursor cells (FAPs) that modulate the regenerative response3, along with signals arising from nerve and capillary terminals and other interstitial cells. For cell-based therapeutic purposes, it would thus be desirable to obtain and characterize the diverse types of human muscle precursor cells from an accessible source.

Most protocols of human satellite cell isolation rely on the purification of cell subpopulations by flow cytometry or magnetic separation of muscle-derived cell suspensions through differential expression of membrane markers4–21. Despite the important recent advances in the purification and characterization of human satellite cells, they are still isolated in small numbers out of muscle biopsies of a limited size (typically of 50–100 mg; there are between 500–1,000 satellite cells per mm3 20), and the stem cells present restricted expansion capacities in vitro22,23. For these reasons, myoblasts (a heterogeneous mixture of semi-purified CD56+ cells24,25) have been mostly used in clinical trials to date, since they expand well in vitro26,27. However, the results of expanded myoblast cell infusion in a plethora of clinical trials targeting muscle regeneration have been disappointing28–32. Some authors argue that the large expansion rates of myoblasts have brought up excessive differentiation in culture and hence low survival, migration and fusogenic capacities when cells are transplanted in vivo33–35. Of note, more experiments must be done with human myoblasts to ensure that this is also the case in humans36.

A still relatively unexplored possibility is the growth of human muscle precursor cells in three-dimensional myosphere cultures37. In mice, myospheres represent a mixture of ITGA7+ Myf5+ MyoD+Pax7+ myogenic (possibly satellite cells) precursor cells and non-myogenic (possibly FAPs) precursors characterized as PDGFRα+Sca−1+38,39. Since both precursor cell populations are required for muscular regeneration, myosphere cultures would have the advantage of providing two precursor cell types instead of one, when compared to alternative satellite cell isolation strategies. Human myosphere cultures present at least a CD31−CD34−CD45−CD56−CD117−CD29+CD73+CD90+CD105+ “mesenchymal” stem cell population, which possibly is non-myogenic40 and could be equivalent to FAPs, and a CD34−CD45−PAX7+CD56+ALDH1+ myogenic precursor cell population that possibly corresponds to satellite cells41.

In this article, we propose human cremaster muscle as a convenient source of muscle-derived stem/precursor cells in male donors. This is a striated muscle not inserted through a tendon, and which also contains a variable number of smooth muscle fibres42. Predominantly, it is composed of type I (slow) fibres, although it also contains some of IIB (very fast) type. The function of this muscle in the adult is to contribute to the thermoregulation and protection of testicles, and we postulate it should be classified as an evolutionary remnant of mammalian Panniculus carnosus muscle43. Thanks to the cremasteric reflex, its electrophysiological properties are well known. The muscle is densely innervated and presents numerous motor endplates, which may be the reason underlying its abundant spontaneous discharges42. In children, no sexual dimorphism was observed in cremaster muscle except for a larger diameter of fibres in males, as it is commonly observed in most muscular groups44. In embryonic development, cremaster muscle derives from the gubernaculum, independent of the internal oblique muscle of the abdomen, and it performs a key function in testicular descent45–47. However, some authors propose that striated cremaster fibres transdifferentiate from smooth muscle instead48, as it may happen in other muscles of the genitourinary tract, such as the rhabdosphincter49.

Since alternative donor biopsy sites must be identified in diseases where muscle affection is widespread, we here aimed to histologically characterize the cremaster muscle with regard number of satellite cells and regenerative fibres, and to isolate and characterize human cremaster muscle-derived stem/precursor cells in adult male donors to evaluate this muscle as a novel source of myogenic precursor cells.

Results

Histological characterization of human cremaster muscle

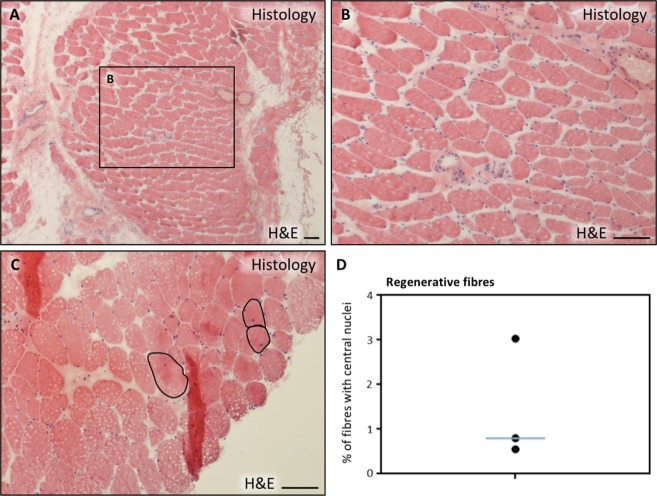

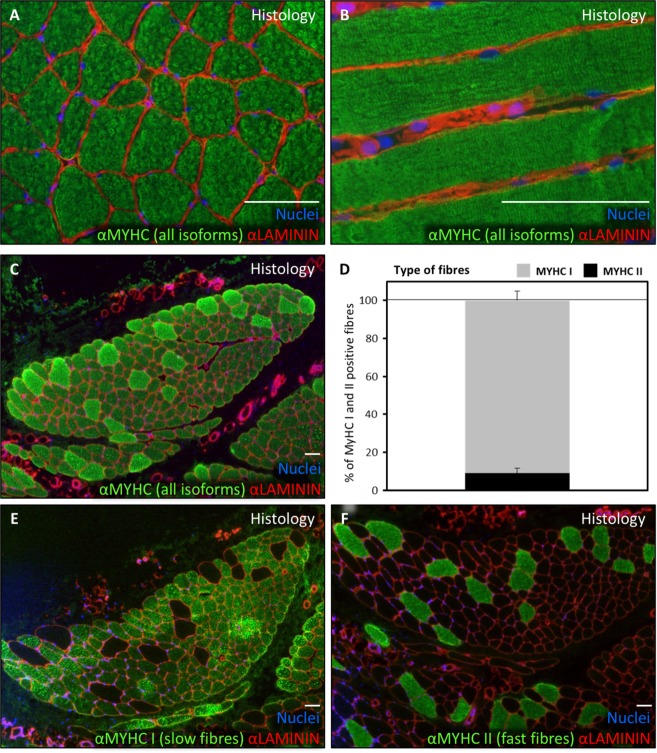

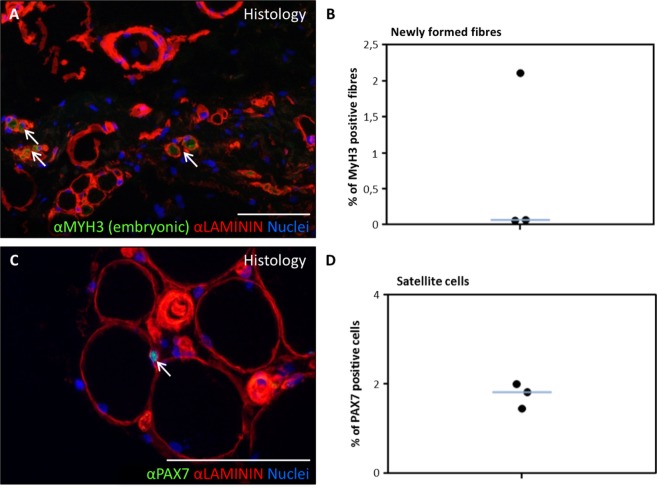

The cremaster muscle is surgically accessible in the context of male patients undergoing routine surgery for urogenital pathology (mainly hydrocele and varicocele). Histological characterization (haematoxylin and eosin stain) of cremaster muscle biopsies of these patients (Table 1) showed the presence of a discrete percentage (0.5–3%) of centrally nucleated, regenerative striated fibres as well as some interspersed smooth muscle fibres (Fig. 1), as expected. By immunofluorescence, striated fibre sarcomeres were clearly delineated by myosin heavy chain (MYHC all fibres) antibody staining, and muscle fibres were surrounded by LAMININ positive basal membrane (Fig. 2A,B). Predominance of type I (slow) fibres and the presence of fewer number of type II (fast) fibres was corroborated by the expression of specific MYHC I and MYHC II isoforms, respectively (Fig. 2C–F). The existence of newly formed fibres was confirmed by expression of the embryonic isoform of MYHC, MYH3 (Fig. 3A,B, arrows). To quantify the number of satellite cells in situ, the number of PAX7+ nuclei that were surrounded by LAMININ+ basal membrane was determined (Fig. 3C,D, arrow). A proportion of 1.8 ± 0.3% satellite cells were calculated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of biopsy donors in this study.

| Donor # | Sex | Age (y) | Department | Pathology | Tissuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 35 | Urology | Spermatic cord cyst | Non-muscle tissue |

| 2 | Male | 26 | Urology | Varicocele | Cremaster |

| 3 | Male | 22 | Urology | Varicocele | Cremaster |

| 4 | Male | 64 | Urology | Hydrocele | Non-muscle tissue |

| 5 | Male | 48 | Urology | Hydrocele | Non-muscle tissue |

| 6 | Male | 50 | Urology | Hydrocele | Cremaster |

| 7 | Male | 31 | Urology | Varicocele | Cremaster |

| 8 | Male | 17 | Urology | Varicocele | Cremaster |

| 9 | Male | 20 | Urology | Hydrocele | Cremaster |

| 10 | Male | 35 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 11 | Male | 51 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 12 | Male | 71 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 13 | Male | 29 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 14 | Male | 50 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 15 | Male | 70 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 16 | Male | 45 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 17 | Male | 86 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 18 | Male | 74 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

| 19 | Male | 41 | General surgery | Inguinal hernia | Cremaster |

aSome biopsies were taken for negative control and included non-muscle tissue adjacent to the Cremaster muscle.

Figure 1.

Histological characterization of human cremaster muscle. (A–C) Histological section of cremaster muscle stained with H&E where detailed fibre morphology can be seen (A,B) and the presence of regenerative fibres with central nuclei is highlighted (C,D) Percentage of centrally nucleated fibres as quantified in three independent biopsies. The blue line represents the median value of the data. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Predominance of slow type fibres in human cremaster muscle. (A,B) Muscle sections were analysed by immunofluorescence to show MYHC expression in the fibres (all isoforms, green) and LAMININ expression surrounding the fibres (red). (C,D) Fibre type predominance study through myosin heavy chain isoform expression analysis by immunofluorescence (C,E,F) and resulting distinct fibre quantification graph showing median and standard deviation obtained from three independent biopsies (D). In A, B, C, E and F panels LAMININ is shown in red and nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

Figure 3.

Satellite cells and regenerative fibres in human cremaster muscle. (A,B) Percentage of MYH3 (embryonic myosin isoform)-expressing fibres detected by immunofluorescence (green), surrounded by LAMININ (red). Arrows in (A) show regenerative fibres and the graph (B) shows regenerative fibres as a percentage of total fibres, as quantified in three independent biopsies. The blue line represents the median value of the data. (C,D) Immunofluorescence detection of PAX7+ satellite cells (green) located in their niche between two LAMININ positive layers (red). The arrow in (C) points to a satellite cell. (D) Percentage of PAX7 positive nuclei as quantified in three independent biopsies. The blue line represents the median value of the data. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

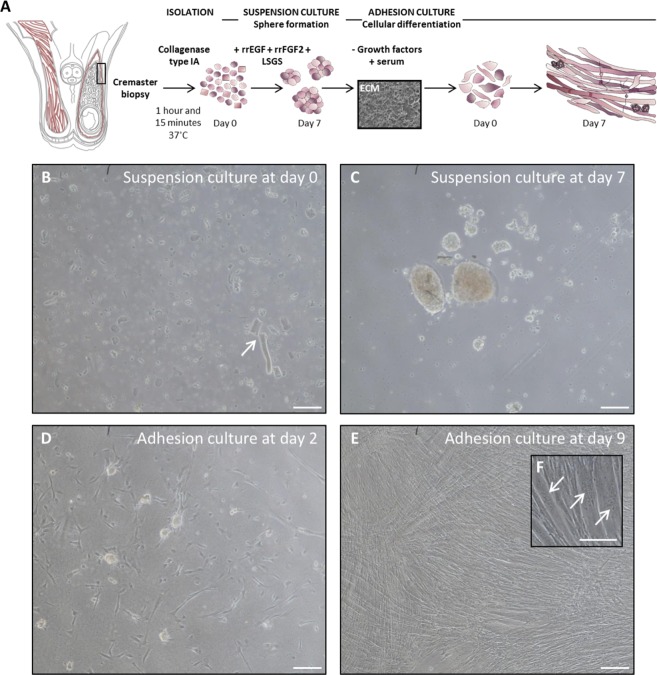

In vitro myotube formation from human cremaster muscle-derived cells

To evaluate in vitro myogenic potential of human cremaster muscle-derived cells, a protocol previously used in mouse cultures50 was adapted to human biopsies (Fig. 4A). At day 0 (d0), suspension cultures presented abundant cellular debris and dead cells as well as unicellular suspensions and muscle tissue remnants (Fig. 4B, arrow). After 7 days of myosphere culture, cells formed spheres of variable size (Fig. 4C). These spheres were then put into differentiation culture51. The cells adhered to the substrate and started forming multinucleated myotubes by d2 (Fig. 4D) and, by d9, myotubes occupied most of the culture surface (Fig. 4E,F, arrows). These results suggested that human cremaster muscle-derived cells adopted a myogenic commitment in vitro in response to appropriate cues.

Figure 4.

In vitro isolation, expansion and differentiation of human cremaster muscle-derived myogenic precursor cells. (A) Schematic representation of the male reproductive system anatomy, showing cremaster muscle (red) and the biopsy sample zone is highlighted by a rectangle. Outline of the myosphere suspension culture and myotube differentiation (adhesion culture) steps. (B,C) Optical microscope images of the suspension culture showing cells and tissue fragments (arrow) at day 0 (B) and spheres at day 7 (C). (D–F) Optical microscope images of the adhesion culture at day 2 (D) and day 9 (E,F), where multinucleated myotubes (arrows) become predominant. Scale bars, 100 μm.

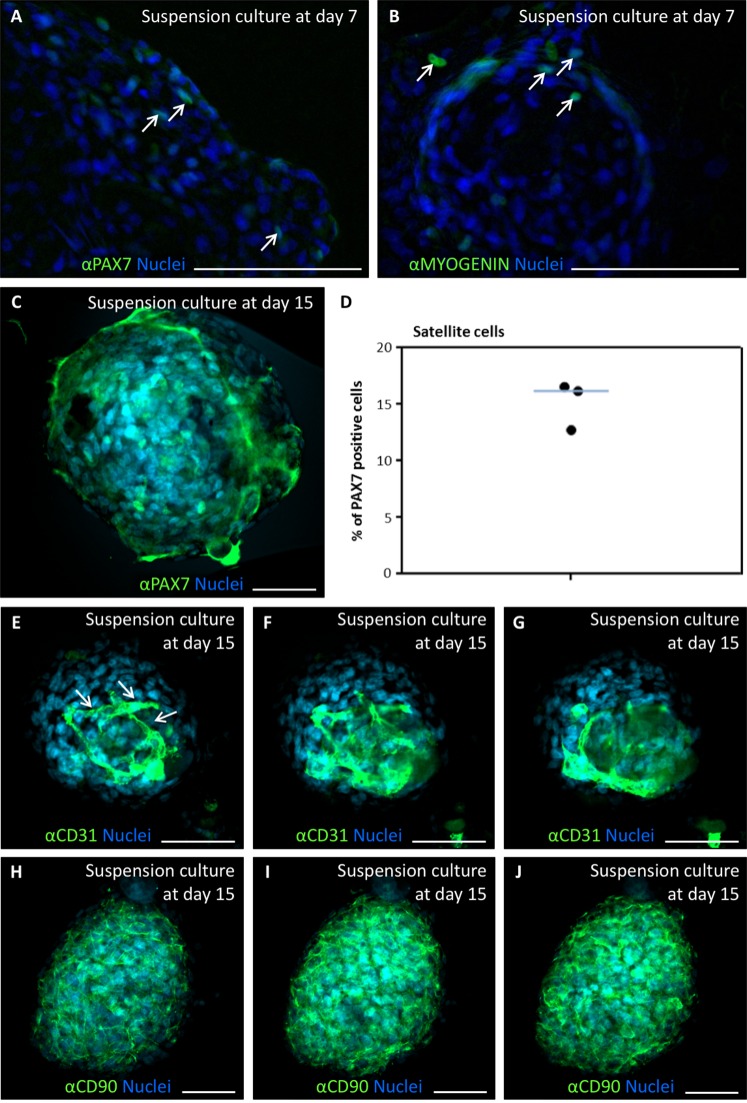

To demonstrate the presence of myogenic cells in these cultures, myogenic markers PAX7 and MYOGENIN were detected by immunofluorescence in d7 myosphere cultures, showing discrete numbers of positive cells in the myospheres (Fig. 5A,B, arrows). Satellite (PAX7+) cells were quantified at day 15 of suspension culture (Fig. 5C). A median proportion of 16.2% PAX7+ cells (Fig. 5D) indicated that the sphere culture differentially enriched satellite cells over other cell types present at day 0, as previously observed in mouse dermosphere cultures50. To determine if endothelial (CD31+) cells and mesenchymal (CD90+) cells were also present in the cremaster-derived myosphere cultures, the presence of cells positive for these markers was analysed by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Both CD31+ and CD90+ cells were easily detected, although quantification was difficult due to overlapping of the signal with numerous nuclei in the confocal sections (Fig. 5E–J). Interestingly, CD31+ cells seemed to form tube-like structures, reminiscent of angiotubes (Fig. 5E–G, arrows).

Figure 5.

Expression of myogenic, endothelial and mesenchymal markers during in vitro expansion of human cremaster muscle-derived myogenic precursor cells. (A–C) Immunofluorescence analysis of myogenic protein expression in d7 (A,B) and d15-cultured myospheres (C). Arrows indicate cells positive for PAX7 (green, A), and MYOGENIN (green, B). Confocal microscope image showing PAX7 positive cells (green, C). (D) Percentage of satellite cells (PAX7 positive cells) as quantified in several spheres from three independent biopsies. The blue line represents the median value of the data. (E–J) Serial confocal microscope images of d15-cultured spheres analysed by immunofluorescence for the detection of endothelial cell marker CD31 (E–G) and mesenchymal cell marker CD90 (H–J). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm (A,B) and 50 μm (C,E–J).

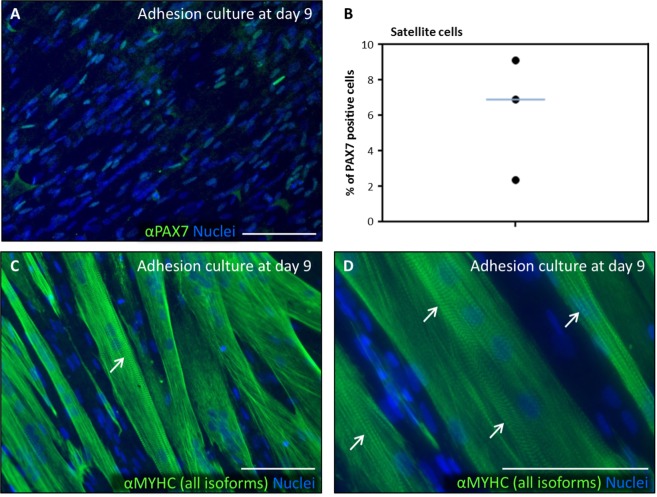

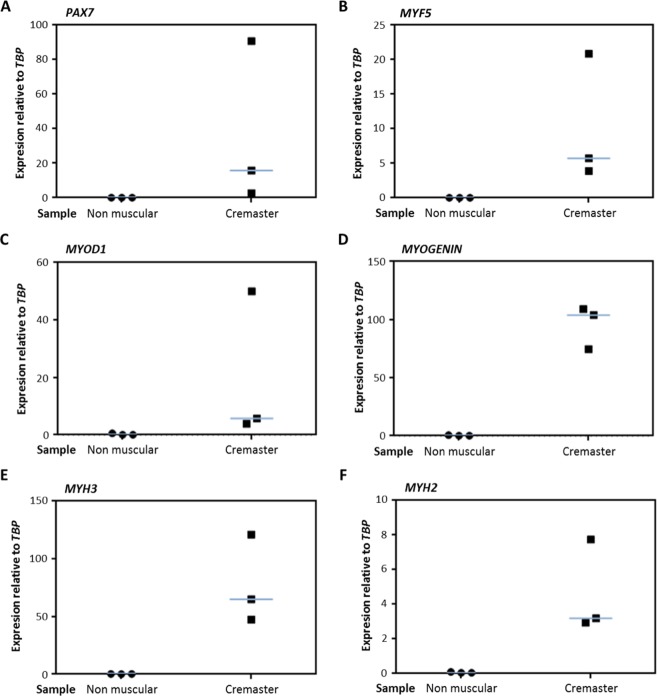

After 9 days in differentiation culture (Fig. 6), single cells expressing PAX7 were still detected (Fig. 6A), with a median proportion of 6.9% PAX7+ cells (Fig. 6B). They were often observed in positions adjacent to MYHC+ multinucleated myotubes, which presented characteristic sarcomeric striations (Fig. 6C,D, arrows). The expression of myogenic genes was confirmed by qRT-PCR after 9 days in differentiation culture (Fig. 7). As negative control, patient biopsies that were taken from non-muscle tissue adjacent to the cremaster were used (Table 1). The cultures that were derived from cremaster muscle, but never those derived from non-muscle tissue, expressed variable but consistent amounts of the myogenic genes PAX7, MYF5, MYOD1, MYOGENIN, MYH3 and MYH2 (Fig. 7A–F). These results confirmed that cells of myogenic commitment were maintained by myosphere culture and were differentiated to myotubes in adhesion culture.

Figure 6.

Expression of myogenic proteins during in vitro differentiation of human cremaster muscle-derived myogenic precursor cells. Immunofluorescence analysis of myogenic protein expression in d9-adhesion culture showed PAX7 positive cells (green, A), and MYHC (all isoforms) positive myotubes (green, C–D). Arrows indicate sarcomeric striations. (C) Percentage of PAX7 positive nuclei as quantified in three independent biopsies. The blue line represents the median value of the data. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

Figure 7.

Expression of myogenic genes during in vitro differentiation of human cremaster muscle-derived myogenic precursor cells by qRT-PCR. At d9-differentiation cultures, the expression of myogenic genes PAX7 (A), MYF5 (B), MYOD1 (C), MYOGENIN (D), MYH3 (E) and MYH2 (F) was quantified by qRT-PCR. The expression values from three independent cremaster muscle biopsies and noncremasteric biopsies are shown relative to endogenous control mRNA TBP. The blue lines represent the median values of the data.

In vivo regenerative potential of human cremaster muscle-derived cells in a mouse model of muscular damage

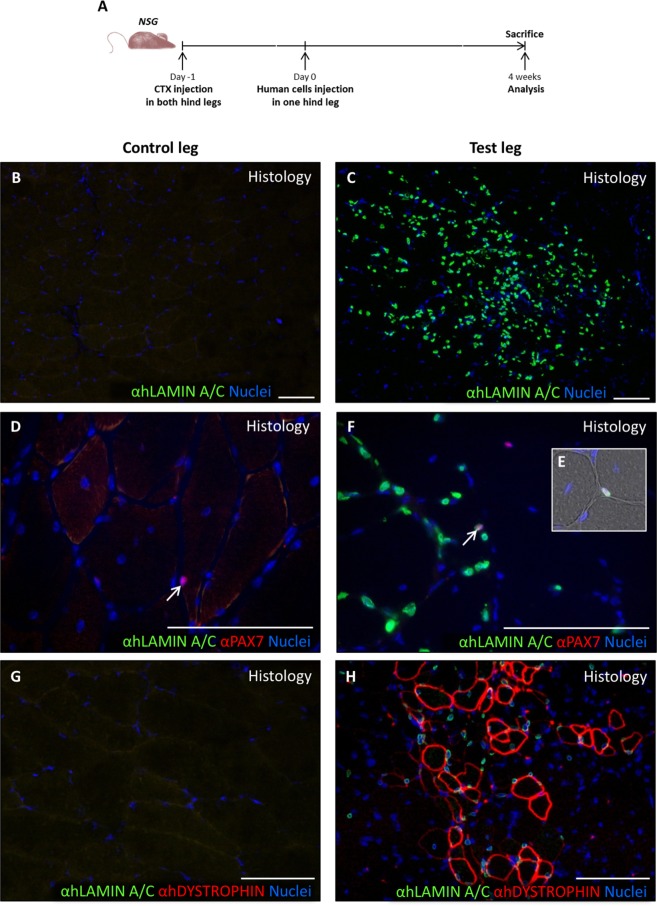

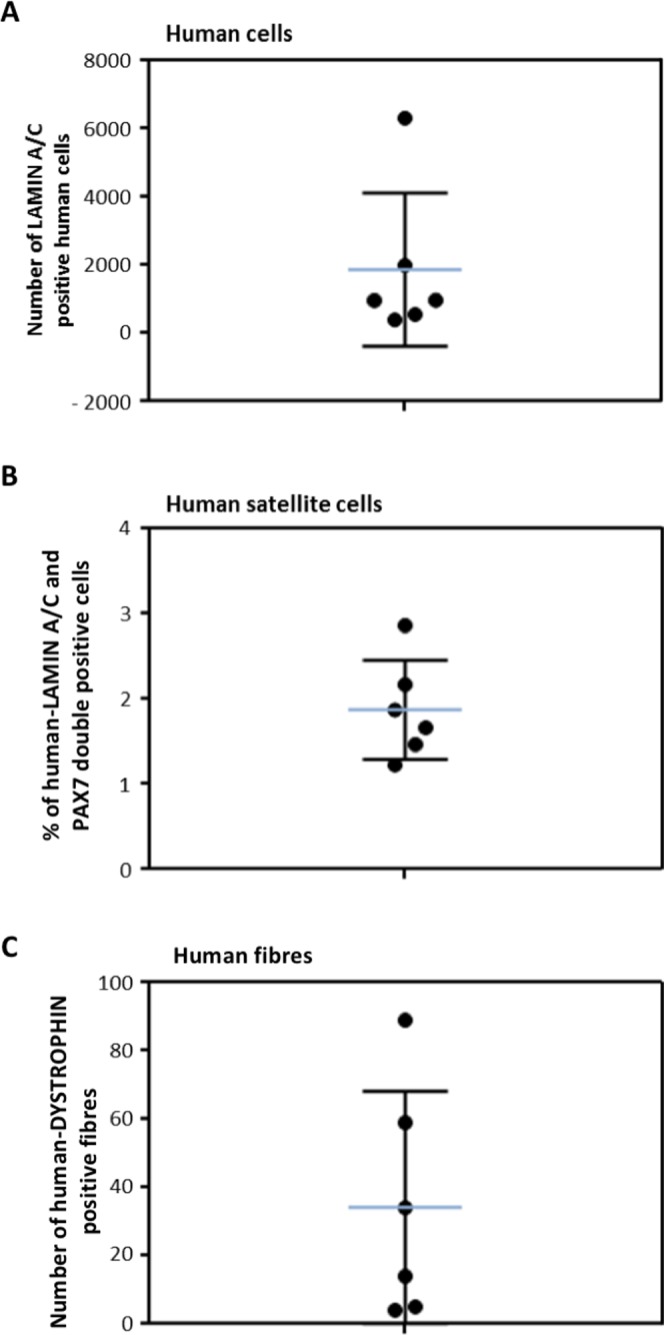

To evaluate the potential use of human cremaster muscle-derived cells in future cell-based therapy trials, we analysed their regenerative potential in a proof-of-concept preclinical assay of muscle regeneration (Fig. 8A)52,53. Four weeks after cell injection, TA muscles were extracted and analysed by immunofluorescence. In the experimental TA muscle group (N = 6), a variable number of human cells was detected by their reactivity for the highly specific anti-human LAMIN A/C antibody, which was absent in the control leg (Fig. 8B,C). Of the LAMIN A/C+ cells, a relatively small percentage co-expressed the satellite cell marker PAX7 (Fig. 8D–F, arrows). The number of muscle fibres of human origin, as determined by the expression of human DYSTROPHIN by immunofluorescence (Fig. 8G,H), correlated quite well to the number of human cells detected per mice. Quantification of these human-specific markers (Fig. 9A,B) showed an average number of 1864 ± 2247 LAMIN A/C+ cells per section, of which 1.8 ± 0.6% were also PAX7+. The number of fibres of human origin (detected as hDYSTROPHIN+) was highly variable, 34.2 ± 34.0 fibres per section (Fig. 9C). These results suggested that human cremaster muscle-derived stem cells survived to the transplants and contributed to muscle regeneration in response to cardiotoxin damage.

Figure 8.

In vivo differentiation of human cremaster muscle-derived myogenic precursor cells. (A) Outline of the experimental design. (B–H) Immunofluorescence of histological sections from the control TA group (B,D,G) and the experimental TA group (C,F,H), respectively. (B,C) Histological analysis of the grafted cell survival through human LAMIN A/C detection by immunofluorescence (green). (D–F) Detection of human LAMIN A/C (green) and PAX7 (red) expressing satellite cells localized in their niche by immunofluorescence (arrows, E). (G,H) Detection of human LAMIN A/C (green) and human DYSTROPHIN (red) positive fibres. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

Figure 9.

In vivo regenerative capacity of human cremaster muscle-derived myogenic precursor cells. (A) Quantification of the human LAMIN A/C positive nuclei detected in each mouse (N = 6). (B) Percentage of satellite cells (PAX7 positive cells) in relation to the total human nuclei detected in each mouse. (C) Quantification of the number of human DYSTROPHIN+ fibres per mouse. Median and standard deviation of the data are represented with blue and black lines, respectively.

Discussion

Cell-based therapeutic approaches for muscle regeneration may be applicable in congenital myopathies54, muscular dystrophies and other neuromuscular diseases55, cardiac dysfunction56, volumetric muscle mass loss, cachexia and sarcopenia57. However, several of these pathologies affect relevant volumes of muscle tissue and this fact compromises the feasibility of cell-based approaches. For this reason, smaller muscle groups such as those affected in oculopharyngeal or in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophies may be approached with greater chances of success35,58. Anal and urinary sphincter deficiencies may also be excellent targets for these therapies59,60 since the muscle volume to be regenerated is small and the defect accessible via minimally invasive surgical approaches. For any of these pathologies it will be instrumental that adequate animal models are developed due to the inherent variability seen in the clinical setting61.

Despite the fact that the Panniculus carnosus muscle is vestigial in humans43, we were interested in testing if those evolutionary remnants still available in human beings would be of use to isolate muscle satellite cells of possible use in cell therapy, as we had previously done in the mouse50. The cremaster muscle was selected because it can be biopsied through a small inguinal incision which is routinely performed in several common urogenital surgeries in males. It is a predominantly slow twitch muscle and thus the number of satellite cells would be expected to be higher, although this seems to be dependent on muscle loading62. In this work, we found a satellite cell proportion in situ that seems to be below what has been established for other muscle groups63. The percentage of centrally nucleated (regenerative) fibres was on a similar range to other muscle groups64,65.

Nevertheless, we have also shown that cremasteric myogenic precursor cells can be maintained and expanded in vitro reaching sizable numbers (about 15% of the myosphere cells), and that the expanded cells retain muscle regenerative capacities in vivo. The main limitations of this initial study are: (i) the low number of samples analysed; (ii) the fact that this muscle can only be found in males, leaving aside half of the adult population; and (iii) that we characterized samples from patients and not from healthy individuals. For instance, higher grade varicoceles might be associated with denervation of cremaster muscle, causing small group atrophy66. These issues will be addressed by future investigations.

To apply cremaster-derived myogenic precursor cells in muscle pathology, a number of obstacles must be overcome: first, it must be studied if this muscle is affected by the relevant pathology at study, and second, an analogous muscle group should be found in adult women. A possible candidate could be the round ligament of the uterus, which is also composed of striated and smooth muscle fibres and that extends from uterus to deep inguinal ring, sometimes inserting itself into adipose tissue and skin of labia majora.

Importantly, the human cremaster muscle-derived myospheres were also shown to present mesenchymal (CD90+) and endothelial (CD31+) cells, and we postulate that, most likely, they will contain Schwann cells as well67. Human bone marrow-derived mesenspheres are CD90+, and contain bone marrow-derived stem cells which preserve an immature phenotype68. Tissue-resident CD31+ endothelial precursor cells have previously been isolated from mouse muscle69. Endothelial cells in co-culture spheres may self-assemble and form reticulated structures, as demonstrated here and previously seen in other systems70,71. The presence of both of these cell types might contribute to an improved vascularization of the affected area, as demonstrated in bone defects72. Finally, if Schwann cells and other peripheral nerve-derived cells were also present in these spheres, they might support reinnervation and regeneration of the degenerated tissue73. We would like to propose that, due to their origin and location, the mix of precursor cells present in the myospheres may be a good candidate to be used in cell therapy approaches of stress urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Ideally, the isolation protocol should be adjusted so that precursor cell extraction and treatment may be done in the course of a single intervention74,75. Similarly, CD56+ myoblasts from pyramidal muscle have been obtained from radical prostatectomy patients76 and myoblasts derived from rectus muscles in patients undergoing open abdominal surgery77. Our approach would provide a more comprehensive pro-regenerative cellular mix.

Conclusions

Human cremaster is a predominantly low twitch muscle with relatively few satellite cells and some regenerative fibres in situ. Cremaster-derived myogenic precursor cells can be isolated and expanded as myospheres, and the expanded cells retain muscle regenerative capacities in vivo. We propose that these precursors are a good candidate for cell therapy approaches of skeletal muscle. Due to their location and developmental origin, they might be best suited for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy.

Methods

Aim, design and setting of the study

This study aimed to characterize in vitro and in vivo human cremaster muscle stem cells isolated from male donor biopsies (N = 19) and propagated in vitro in the form of myospheres.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol to obtain cremaster and non-muscle tissue biopsies from patients after signature of the informed consents followed all relevant legal and ethical regulations, and was approved by the Ethics and the Scientific Committees of the HUVV (CEUMA No. 79-2015-A). Animal experiments were carried out following all relevant legal and ethical regulations, and according to protocols approved by the Biodonostia Animal Care Committee (CEEA16/008).

Human cremaster muscle biopsies

Upon informed consent signature from male patients undergoing inguinal hernia (N = 10), hydrocele (N = 4), varicocele (N = 4), or spermatic cord cyst (N = 1) surgeries at the Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital (HUVV), a 1–3 cm2 cremaster muscle biopsy (or adjacent non-muscle tissue for negative controls) was collected during regular surgery procedure without adding any morbidity to the process. Biopsy samples were managed by the HUVV-IBIMA Biobank. Men with uro-oncologic disease or other diseases that could affect the scrotal area were not included as donors. The characteristics of biopsy donors are described in Table 1.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Deidentified human cremaster biopsies from surgery room (processed within 30 min of the procedure) were embedded in OCT medium (Q-Path, VWR), frozen by immersion in isopentane previously cooled in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until usage. Cryostat sections (7–10 μm) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Panreac), and mounted with Shandon Consul-Mount mounting media (Fisher Scientific) according to standard procedures. For immunohistochemistry, biopsy sections from OCT blocks were dried; and fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde aqueous solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences) 10 min at room temperature (RT) or directly blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at RT; and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody in 1% BSA solution. Slides were rinsed in PBS containing 0.025% Triton X-100 (Amresco) and incubated for at least 1 h with the appropriate secondary antibody in the same solution used for blocking. The slides were rinsed with PBS containing 0.025% Triton X-100. Nuclei were stained with 10 μg/ml Hoechst solution (Santa Cruz, SC-394039) for 2 min and slides were mounted with Fluoro-Gel mounting media (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Cat #17985–10). Sections were imaged with a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope.

Isolation, proliferation, and striated muscle differentiation of muscle precursor cells

Deidentified human cremaster biopsies from surgery room (processed within 30 min of the procedure) were transported immersed on HBSS (ThermoFisher, 14170-088) with 1% Fungizone and 1% Penicillin on ice. Biopsies were mechanically dissociated and digested with a collagenase type IA solution (Sigma-Aldrich, 650 CDU/mg, 2 mg/ml) for 1–2 h at 37 °C under gentle shaking. Collagenase was inactivated with culture media and the resulted digested tissue was filtered through 40-μm Nylon Cell Strainers (Corning). Collagenase was removed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min at RT.

The cellular pellet containing muscle-derived cells was resuspended and cultured in suspension as described50, to promote myosphere expansion in proliferation medium [Neurobasal A (ThermoFisher) with 2% 50X B27 supplement (ThermoFisher), 1% 200 mM L-glutamine [Sigma-Aldrich], and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100×)], supplemented every two days with 2% low serum growth supplement (1×, ThermoFisher), 40 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (R&D Systems), and 80 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2; R&D Systems). Differentiation of myospheres was performed in adherent culture as described51. First, extracellular matrix-coated glass coverslips were prepared by incubating a solution of Cultrex basement membrane extract (2.77 mg/mL; Trevigen), Netrin-4 (0.83 μg/mL), Netrin-G1a (0.83 μg/mL), and low molecular weight hyaluronan (2.5 mg/mL; R&D Systems) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). For muscle induction, primary myospheres were gently disaggregated with a 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and resuspended in proliferation medium without added growth factors plus 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC), before plating onto coated coverslips at a density of 79,000 cells/cm2. Every 2 days, half of the medium was replaced with a fresh medium.

Immunofluorescence of myogenic markers in myospheres

Immunofluorescence was performed in suspended sphere cultures. For suspended spheres, 1 ml of suspended culture was collected and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5′ at RT. The cell pellet was washed with 1X PBS and fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde aqueous solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 10 min at RT in a rotating station. Spheres were washed in PBS, permeabilized for 1 h in 0.3% Triton X-100 (Amresco) in PBS (PBS-T) and 5% normal donkey serum (Santa Cruz, SC-2044) at RT in the rotation station. Spheres were incubated with the appropriate primary antibody diluted in PBS-T overnight at 4 °C, rotating. Next, cells were 1X PBS-washed 3 times (5 min each) and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody diluted in PBS-T for 1 h at RT in darkness and rotating. Prior to mounting in Fluoro-Gel, spheres were incubated with 10 μg/ml Hoechst (Santa Cruz, SC-394039) for 2 min rotating at RT and in darkness and washed with 1X PBS. Images were obtained by using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope coupled to a Nikon Digital Sight camera or a Zeiss LSM800 Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope. Confocal z-stack images were taken with the 25x objective (1.96 μm between slides). Images were processed using ZEN blue software and ImageJ software.

Gene expression in differentiated cultures

Total RNA was extracted from differentiated cultures from cremaster biopsies and non-cremasteric biopsies by miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and converted into complementary DNA with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Each cDNA sample was amplified in triplicates for the real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis which was carried out using Taqman gene expression assays in the 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The cycling conditions were 95 °C/10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C/15 s, 60 °C/1 min in a reaction mixture that contained 1x Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix and 1x Assay Mix in a final volume of 20 μl. The expression of the genes was represented relative to the housekeep gene Tbp expression.

Intramuscular cell transplantation

Animal experiments were carried out following the experimental design of Darabi and colleagues52,53. One day before cell transplantation, 10-week old immunocompromised NSG mice (NOD.Cg-PrKdcsidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, JAX 005557) (N = 6) were anesthetized with isoflurane and Tibialis anterior (TA) muscle damage was induced in both rear limbs through injection of 7.5 μL of 100 μM cardiotoxin (CTX, Latoxan) by using a 26 s gauge Hamilton syringe (bevelled tip). 24 h later, cells were injected (235,000 cells in 15 μl of PBS pH 7.2) into right TA muscles, whereas the left TA muscles received the same volume of PBS (negative controls). Before transplantation, human cremaster-derived precursor cells had been cultured as myospheres for 7 days, dissociated with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, filtered through 70 μm Nylon Cell Strainers (Corning) and resuspended in 1X PBS. Animals were caged by groups with ad libitum access to food and water and they were monitored for 4 weeks until sacrifice. Animals were sacrificed with CO2 and engrafted muscles were removed and processed for histological analysis. Seven-micrometer serial transverse cryosections were cut at intervals of 100 μm throughout the entire muscles.

Antibodies list

Primary antibodies used were anti-CD31 (CD31) (M0823; 1:30; Dako); anti-CD90 (CD90) (ab133350; 1:200; Abcam); anti-hDystrophin (DYSTROPHIN) (NCL-DYS3; 1:20; Leica); anti-hLamin A/C (LAMIN A/C) (ab108595; 1:200; Abcam); anti-Laminin (LAMININ) (L9393; 1:200; Sigma); anti-MYOD (MyoD1) (SC-377460; 1:50; Santa Cruz); anti-myosin heavy chain all fibers (MYHC) (A4-1025-c; 1:200; DSHB); anti-myosin heavy chain embryonic (MYH3) (F1.652; 1:50; DSHB); anti-myosin heavy chain fast fibers (MYHC II) (A4.74; 1:200; DSHB); anti-myosin heavy chain slow fibers (MYHC I) (A4.840; 1:200 M; DSHB); and anti-PAX7 (Pax7) (Pax7-c; 1:50; DSHB). Secondary antibodies used were donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A21202; 1:500; Thermo Fisher), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A21042; 1:500; Thermo Fisher), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 (A31570; 1:500; Thermo Fisher), donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (A21206; 1:500; Thermo Fisher), and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (A31572; 1:500; Thermo Fisher).

Acknowledgements

We thank patients and medical personnel for their generous involvement in the study. We also acknowledge the help of Biodonostia Animal and Experimental Operations Facility. This work was supported by grants from Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (RTC-2015-3750-1) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI13/02172, PI16/01430) to A.I., co-funded by the European Union (ERDF/ESF, ‘Investing in your future’). N.N.-G. received a studentship from the Department of Education, University and Research of the Basque Government (PRE2013-1-1168). A.L.M. was funded by grants from FIS (PI17/01841 and PI14/00436), CIBERNED and the Basque Government (2015/11038, RIS3 2017222021 and BIO16/ER/022). M.F.L.-C. was supported by the Servicio Andaluz de Salud from the Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía, grant PI 0222-2014, co-funded by the European Union (ERDF/ESF). I.M.A was funded by grants from Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (PEJ-2014-P-01215 and FJCI-2016-28121).

Author Contributions

N.N.-G. performed most of the research work. N.N.-G. and M.G. performed in vivo cell transplantation and histological assays. I.M.A., B.H.-I., R.d.L.-D. and M.F.L. collected patient biopsies. V.P.-L. and S.F.-A. cultured myospheres and acquired confocal images. P.M.B. and M.A.F. contributed ideas and support to the project. A.L.M. and M.F.L. co-directed and co-financed the work. A.I. directed and financed the work, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing Interests

The research shown in this manuscript is covered by Spanish patent application no. P201830244, jointly owned by Servicio Andaluz de Salud and Administración General de la Comunidad Autónoma de Euskadi. AI, ALM, NN-G, MG, BH-I, MFL, and IMA are listed as inventors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

María Fernanda Lara, Email: mf.lara@fimabis.org.

Ander Izeta, Email: ander.izeta@biodonostia.org.

References

- 1.Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. The Journal of biophysical and biochemical cytology. 1961;9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chal J, Pourquie O. Making muscle: skeletal myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Development. 2017;144:2104–2122. doi: 10.1242/dev.151035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tucciarone, L. et al. Advanced methods to study the cross talk between fibro-adipogenic progenitors and muscle stem cells. In Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Methods and Protocols (ed. Bernardini, C.) 231–256 (Springer New York, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Alexander MS, et al. CD82 Is a Marker for Prospective Isolation of Human Muscle Satellite Cells and Is Linked to Muscular Dystrophies. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bareja A, et al. Human and mouse skeletal muscle stem cells: convergent and divergent mechanisms of myogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benchaouir R, et al. Restoration of human dystrophin following transplantation of exon-skipping-engineered DMD patient stem cells into dystrophic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:646–657. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castiglioni A, et al. Isolation of Progenitors that Exhibit Myogenic/Osteogenic Bipotency In Vitro by Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting from Human Fetal Muscle. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charville GW, et al. Ex Vivo Expansion and In Vivo Self-Renewal of Human Muscle Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jean E, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity promotes survival of human muscle precursor cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:119–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecourt S, et al. Characterization of distinct mesenchymal-like cell populations from human skeletal muscle in situ and in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2513–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng J, et al. Human skeletal muscle-derived CD133(+) cells form functional satellite cells after intramuscular transplantation in immunodeficient host mice. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1008–1017. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negroni E, et al. In vivo myogenic potential of human CD133+ muscle-derived stem cells: a quantitative study. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1771–1778. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisani DF, et al. Hierarchization of myogenic and adipogenic progenitors within human skeletal muscle. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2182–2194. doi: 10.1002/stem.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pisani DF, et al. Isolation of a highly myogenic CD34-negative subset of human skeletal muscle cells free of adipogenic potential. Stem Cells. 2010;28:753–764. doi: 10.1002/stem.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamaki T, et al. Therapeutic isolation and expansion of human skeletal muscle-derived stem cells for the use of muscle-nerve-blood vessel reconstitution. Front Physiol. 2015;6:165. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torrente Y, et al. Autologous transplantation of muscle-derived CD133+ stem cells in Duchenne muscle patients. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:563–577. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uezumi A, et al. Cell-Surface Protein Profiling Identifies Distinctive Markers of Progenitor Cells in Human Skeletal Muscle. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;7:263–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vauchez K, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity identifies a population of human skeletal muscle cells with high myogenic capacities. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1948–1958. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vella JB, Thompson SD, Bucsek MJ, Song M, Huard J. Murine and human myogenic cells identified by elevated aldehyde dehydrogenase activity: implications for muscle regeneration and repair. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X, et al. Human Satellite Cell Transplantation and Regeneration from Diverse Skeletal Muscles. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng B, et al. Prospective identification of myogenic endothelial cells in human skeletal muscle. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1025–1034. doi: 10.1038/nbt1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brimah K, et al. Human muscle precursor cell regeneration in the mouse host is enhanced by growth factors. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:1109–1124. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper RN, et al. A new immunodeficient mouse model for human myoblast transplantation. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:823–831. doi: 10.1089/104303401750148784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Partridge TA, Grounds M, Sloper JC. Evidence of fusion between host and donor myoblasts in skeletal muscle grafts. Nature. 1978;273:306–308. doi: 10.1038/273306a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stadler G, et al. Establishment of clonal myogenic cell lines from severely affected dystrophic muscles - CDK4 maintains the myogenic population. Skeletal muscle. 2011;1:12. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konigsberg IR. The differentiation of cross-striated myofibrils in short term cell culture. Exp Cell Res. 1960;21:414–420. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(60)90273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott IC, Tomlinson W, Walding A, Isherwood B, Dougall IG. Large-scale isolation of human skeletal muscle satellite cells from post-mortem tissue and development of quantitative assays to evaluate modulators of myogenesis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2013;4:157–169. doi: 10.1007/s13539-012-0097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs D, Morgan JE. Recent progress in satellite cell/myoblast engraftment–relevance for therapy. FEBS J. 2013;280:4281–4293. doi: 10.1111/febs.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cossu G, Sampaolesi M. New therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: challenges, prospects and clinical trials. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mouly V, et al. Myoblast transfer therapy: is there any light at the end of the tunnel? Acta Myol. 2005;24:128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Negroni E, Butler-Browne GS, Mouly V. Myogenic stem cells: regeneration and cell therapy in human skeletal muscle. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2006;54:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tedesco FS, Dellavalle A, Diaz-Manera J, Messina G, Cossu G. Repairing skeletal muscle: regenerative potential of skeletal muscle stem cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:11–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI40373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper RN, et al. Extended amplification in vitro and replicative senescence: key factors implicated in the success of human myoblast transplantation. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1169–1179. doi: 10.1089/104303403322168000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Motohashi N, Asakura A. Muscle satellite cell heterogeneity and self-renewal. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2014;2:1. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2014.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shadrin IY, Khodabukus A, Bursac N. Striated muscle function, regeneration, and repair. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:4175–4202. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2285-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borisov AB. Regeneration of skeletal and cardiac muscle in mammals: do nonprimate models resemble human pathology? Wound Repair Regen. 1999;7:26–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1999.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarig R, Baruchi Z, Fuchs O, Nudel U, Yaffe D. Regeneration and transdifferentiation potential of muscle-derived stem cells propagated as myospheres. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1769–1778. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westerman KA. Myospheres are composed of two cell types: one that is myogenic and a second that is mesenchymal. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westerman KA, Penvose A, Yang Z, Allen PD, Vacanti CA. Adult muscle ‘stem’ cells can be sustained in culture as free-floating myospheres. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1966–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nomura T, et al. Therapeutic potential of stem/progenitor cells in human skeletal muscle for cardiovascular regeneration. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2007;2:293–300. doi: 10.2174/157488807782793808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei Y, et al. Human skeletal muscle-derived stem cells retain stem cell properties after expansion in myosphere culture. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:1016–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayalioglu G, et al. Morphology and innervation of the human cremaster muscle in relation to its function. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:790–796. doi: 10.1002/ar.20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naldaiz-Gastesi N, Bahri OA, Lopez de Munain A, McCullagh KJA, Izeta A. The panniculus carnosus muscle: an evolutionary enigma at the intersection of distinct research fields. J Anat. 2018;233:275–288. doi: 10.1111/joa.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanyel FC, Erdem S, Buyukpamukcu N, Tan E. Cremaster muscle is not sexually dimorphic, but that from boys with undescended testis reflects alterations related to autonomic innervation. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:877–880. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.23959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harnaen EJ, et al. The anatomy of the cremaster muscle during inguinoscrotal testicular descent in the rat. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1982–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lie G, Hutson JM. The role of cremaster muscle in testicular descent in humans and animal models. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:1255–1265. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2983-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders N, Buraundi S, Balic A, Southwell BR, Hutson JM. Cremaster muscle myogenesis in the tip of the rat gubernaculum supports active gubernacular elongation during inguinoscrotal testicular descent. J Urol. 2011;186:1606–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanyel FC, Talim B, Atilla P, Muftuoglu S, Kale G. Myogenesis within the human gubernaculum: histological and immunohistochemical evaluation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:175–179. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borirakchanyavat S, Baskin LS, Kogan BA, Cunha GR. Smooth and striated muscle development in the intrinsic urethral sphincter. J Urol. 1997;158:1119–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64401-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naldaiz-Gastesi N, et al. Identification and Characterization of the Dermal Panniculus Carnosus Muscle Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;7:411–424. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia-Parra P, et al. Murine muscle engineered from dermal precursors: an in vitro model for skeletal muscle generation, degeneration, and fatty infiltration. Tissue engineering. 2014;20:28–41. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2013.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darabi R, et al. Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore DYSTROPHIN and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Darabi R, et al. Functional skeletal muscle regeneration from differentiating embryonic stem cells. Nature medicine. 2008;14:134–143. doi: 10.1038/nm1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jungbluth H, Ochala J, Treves S, Gautel M. Current and future therapeutic approaches to the congenital myopathies. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;64:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Telukuntla KS, Suncion VY, Schulman IH, Hare JM. The advancing field of cell-based therapy: insights and lessons from clinical trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000338. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snijders T, Parise G. Role of muscle stem cells in sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017;20:186–190. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Negroni E, et al. Invited review: Stem cells and muscle diseases: advances in cell therapy strategies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015;41:270–287. doi: 10.1111/nan.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gras S, Tolstrup CK, Lose G. Regenerative medicine provides alternative strategies for the treatment of anal incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:341–350. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams JK, Dean A, Badlani G, Andersson KE. Regenerative Medicine Therapies for Stress Urinary Incontinence. J Urol. 2016;196:1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herrera-Imbroda B, Lara MF, Izeta A, Sievert KD, Hart ML. Stress urinary incontinence animal models as a tool to study cell-based regenerative therapies targeting the urethral sphincter. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;82-83:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kadi F, Charifi N, Henriksson J. The number of satellite cells in slow and fast fibres from human vastus lateralis muscle. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;126:83–87. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmalbruch H, Hellhammer U. The number of satellite cells in normal human muscle. Anat Rec. 1976;185:279–287. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091850303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibbons MC, et al. Histological Evidence of Muscle Degeneration in Advanced Human Rotator Cuff Disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:190–199. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mackey AL, et al. Activation of satellite cells and the regeneration of human skeletal muscle are expedited by ingestion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. FASEB J. 2016;30:2266–2281. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500198R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanji N, Tanji K, Hiruma S, Hashimoto S, Yokoyama M. Histochemical study of human cremaster in varicocele patients. Arch Androl. 2000;45:197–202. doi: 10.1080/01485010050193977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Etxaniz U, et al. Neural-competent cells of adult human dermis belong to the Schwann lineage. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:774–788. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Isern J, et al. Self-renewing human bone marrow mesenspheres promote hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1714–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grenier G, et al. Resident endothelial precursors in muscle, adipose, and dermis contribute to postnatal vasculogenesis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3101–3110. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saleh FA, Whyte M. & Genever, P. G. Effects of endothelial cells on human mesenchymal stem cell activity in a three-dimensional in vitro model. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;22:242–257. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v022a19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sasaki J, et al. Fabrication of Biomimetic Bone Tissue Using Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Three-Dimensional Constructs Incorporating Endothelial Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inglis, S., Kanczler, J. M. & Oreffo, R. O. C. 3D human bone marrow stromal and endothelial cell spheres promote bone healing in an osteogenic niche. FASEB J, fj201801114R, 10.1096/fj.201801114R (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Carr, M. J. et al. Mesenchymal precursor cells in adult nerves contribute to mammalian tissue repair and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell24, 240–256 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Gras S, Klarskov N, Lose G. Intraurethral injection of autologous minced skeletal muscle: a simple surgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2014;192:850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yiou R, et al. Periurethral skeletal myofibre implantation in patients with urinary incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency: a phase I clinical trial. BJU Int. 2013;111:1105–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sumino Y, et al. Long-term cryopreservation of pyramidalis muscle specimens as a source of striated muscle stem cells for treatment of post-prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence. Prostate. 2011;71:1225–1230. doi: 10.1002/pros.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharifiaghdas F, Taheri M, Moghadasali R. Isolation of human adult stem cells from muscle biopsy for future treatment of urinary incontinence. Urol J. 2011;8:54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.