Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the preliminary feasibility, acceptability, and effects of Meaning-Centered Grief Therapy (MCGT) for parents who lost a child to cancer.

Methods:

Parents who lost a child to cancer and who were between six months and six years post-loss and reporting elevated levels of prolonged grief were enrolled in open trials of MCGT, a manualized, one-on-one cognitive-behavioral-existential intervention that utilized psychoeducation, experiential exercises, and structured discussion to explore themes related to meaning, identity, purpose, and legacy. Parents completed 16 weekly sessions, 60–90 minute in length, either in person or through videoconferencing. Parents were administered measures of prolonged grief disorder symptoms, meaning in life, and other assessments of psychological adjustment pre-intervention (T1), mid-intervention (T2), post-intervention (T3), and at three months post-intervention (T4). Descriptive data from both the in-person and videoconferencing open trial were pooled.

Results:

Eight of 11 (72%) enrolled parents started the MCGT intervention, and 6 of 8 (75%) participants completed all 16 sessions. Participants provided positive feedback about MCGT. Results showed post-intervention longitudinal improvements in prolonged grief (d = 1.70), sense of meaning (d = 2.11), depression (d = 0.84), hopelessness (d = 1.01), continuing bonds with their child (d = 1.26), posttraumatic growth (ds = 0.29 – 1.33), positive affect (d = 0.99), and various health-related quality of life domains (ds = 0.46 – 0.71). Most treatment gains were either maintained or increased at the three-month follow-up assessment.

Significance of Results:

Overall, preliminary data suggest that this 16-session, manualized cognitive-behavioral-existential intervention is feasible, acceptable, and associated with transdiagnostic improvements in psychological functioning among parents who have lost a child to cancer. Future research should examine MCGT with a larger sample in a randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: meaning, prolonged grief, existential, bereaved parents, psychotherapy

Introduction

Bereaved parents are at heightened risk for numerous detrimental mental and physical health outcomes, including psychiatric illness, existential suffering, marital problems, and even death (Li, Laursen, Precht, Olsen, & Mortensen, 2005; Li, Precht, Mortensen, & Olsen, 2003; Oliver, 1999). They may also be at increased risk for debilitating protracted grief reactions, such as prolonged grief disorder (PGD). Symptoms of PGD include challenges to one’s sense of identity and feeling that life is empty or meaningless following the loss of an attachment figure (Lichtenthal, Currier, Neimeyer, & Keesee, 2010; Prigerson et al., 2009a; Rando, 1986). Such symptoms appear particularly prominent among parents who have lost a child, who may struggle with their sense of identity and purpose, the meaning of their child’s life, and making sense of the their untimely loss (Davies, 2004; Lichtenthal & Breitbart, 2015; Lichtenthal et al., 2010; Wheeler, 1993). It is thus not surprising that studies have demonstrated the association between challenges with finding meaning and PGD in grieving parents (Davies, 2004; Lichtenthal & Breitbart, 2015; Lichtenthal et al., 2010; Wheeler, 1993).

These central challenges to parents’ sense of meaning, purpose, and identity suggest the potential utility of a meaning-centered therapeutic approach in reducing PGD symptoms. However, while meaning-centered approaches have long been described in the bereavement literature and have been applied in clinical practice, empirical evaluations of such interventions have been limited, particularly following the death of a child (MacKinnon et al., 2015; Neimeyer, in press). Because of the potential therapeutic value of enhancing meaning in bereaved parents (Neimeyer, 2000, 2001b; Neimeyer, in press; Stroebe & Schut, 2001), we developed a manualized intervention, Meaning-Centered Grief Therapy (MCGT), designed to enhance bereaved individuals’ sense of meaning and reduce PGD symptoms. MCGT is an adaptation of Breitbart et al.’s Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP; Breitbart et al., 2018; Breitbart et al., 2012; Breitbart et al., 2010; Breitbart et al., 2015), a brief intervention originally developed to enhance meaning in advanced cancer patients that incorporates the principles of Viktor Frankl’s (1959/1992) logotherapy.

Given that cancer is the leading cause of death by disease among children (American Cancer Society, 2018) and in view of the crisis in meaning that bereaved parents commonly face (Davies, 2004; Lichtenthal & Breitbart, 2015; Lichtenthal et al., 2010; Wheeler, 1993, 2001), our initial application of MCGT has been with parents who have lost a child to cancer. The preliminary development of MCGT followed Stage I of the Stage Model of Behavioral Therapies, including manual writing, pilot testing, and adherence measure development (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001). We obtained feedback from stakeholders, including bereaved parents and grief therapists, that led to important revisions of the MCGT manual (Lichtenthal, Lacey, Roberts, Sweeney, & Slivjak, 2017). We also sought to ensure that bereaved parents would actually be able and willing to use the intervention we developed, and thus, to address the numerous emotional and logistical barriers to accessing support they face (Lichtenthal, Roberts, Bohn, & Farberov, 2011b), we pilot tested delivering this intervention via videoconferencing.

The present pilot study examined the preliminary feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of MCGT in open trials through which the intervention was delivered in person and via videoconferencing. We expected that MCGT would be feasible and acceptable, as evidenced by high treatment attendance, low attrition, and positive feedback. Furthermore, we hypothesized that MCGT would improve parents’ sense of meaning and PGD symptoms. Secondary outcomes included depression, hopelessness, anxiety, continued bonds, attachment dimensions, positive and negative affect, and health-related quality of life.

Methods

Study Design and Procedures

A brief open trial of MCGT was delivered in person with parents (n = 6) with elevated PGD symptoms to evaluate and refine the treatment through active participant feedback, and to identify ways to improve therapeutic alliance to maximize the impact of delivery via videoconferencing. Another brief open trial (n = 5) was then conducted, delivering MCGT via videoconferencing to iron out any logistical challenges in advance of the pilot RCT.

Biological, adoptive, and step-parents who lost a child under the age of 25 to cancer between 6 months and 6 years ago and who were age 18 or over, English speaking, scored 34 or greater on the PG-13 (Prigerson et al., 2009b), and were able to provide informed consent were eligible. PG-13 scores of 34 or greater were selected based on analyses from our earlier research through which we identified 34 as one standard deviation above the sample mean (Lichtenthal, 2011). The cut-off of 34 was then used to identify struggling bereaved parents for qualitative interviews in a prior mixed methods study aimed at obtaining information to develop MCGT (Lichtenthal, 2011). Participating parents were required to be at least six months post-loss to meet criteria for PGD in order to avoid pathologizing of acute bereavement distress in the immediate wake of the death. The upper limit of six year post-loss was chosen because of research demonstrating that for many parents, grief symptoms remain elevated for at least 6 years after their loss (Lannen, Wolfe, Prigerson, Onelov, & Kreicbergs, 2008). For those receiving MCGT through videoconferencing, participants had to reside in the state of New York where the interventionist was licensed. Exclusion criteria included significant cognitive impairment or psychiatric disturbance as determined by the study team.

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK). Potential participants were identified by clinician referral, with approval from the deceased child’s treating physician and hospital administration. Parents were initially contacted with a sensitively-worded letter describing the study and stating that the research staff would be contacting parents within two weeks to discuss their interest. The mailing also provided parents with a self-addressed opt-out postcard and contact information to notify the research staff if they would not like to be contacted further. The research staff called parents within approximately two weeks of the initial letter mailing to assess interest and eligibility. Interested and eligible parents provided informed consent over the phone. For the first open trial, local participants who could likely attend in-person sessions were specifically targeted. In cases in which parents potentially were interested in participating but could not travel for in-person sessions, we arranged to contact them at the initiation of the second open trial, in which MCGT was delivered through videoconferencing. Aside from this, recruitment strategies did not differ between the two open trials.

All therapy sessions were audio-recorded and/or video-recorded with participant permission; audio-recording was required, and video-recording was optional. As is common in initial field testing of interventions (Rounsaville et al., 2001), all MCGT sessions were delivered by the first author, who has extensive training and supervisory experience in MCP and developed the MCGT manual. Participants in the first open trial received 16 weekly sessions of MCGT, 60- to 90-minutes in length, delivered in person. Sessions were delivered through videoconferencing in the second open trial. Explicit instructions, training, and technical support for videoconferencing were provided, with more in-depth training for parents who had limited computer experience.

Assessments were conducted at pre-intervention (T1), mid-intervention (T2), postintervention (T3), and at a three-month post-intervention follow-up (T4). All participants received a $50 incentive for completing the study activities. Participants in both open trials were asked to invite a support provider (e.g., spouse/partner, friend, adult child) to attend the ninth MCGT session. This session was audio and/or video-recorded and a separate consent was obtained from the support provider.

Intervention Description

Overview of MCGT

MCGT is a 16-session, manualized, one-on-one cognitive-behavioral-experiential-existential intervention that uses psychoeducation, structured discussion, and experiential exercises focusing on themes related to meaning, identity, purpose, and legacy. Sessions take between 60 and 90 minutes. Adapted from MCP for advanced cancer patients (Breitbart & Poppito, 2014), MCGT is principle-driven, highlighting four core concepts throughout treatment, namely, helping parents learn to recognize that they have: 1) the ability to choose their attitude in the face of suffering; 2) the ability to connect to sources of meaning in their lives; 3) the ability to choose how they construct meaning about different life events, including the death; and 4) the ability to remain connected to their child and continue their role as parent (Lichtenthal et al., 2017).

MCGT acknowledges the grief that parents are experiencing. By highlighting the choices that they have in a situation that may feel beyond their control, MCGT helps parents learn how to co-exist with their grief through meaning. Specifically, the intervention assists parents with understanding how sources of meaning in their lives can be used as resources to help give them a reason for engaging in life despite their grief. It also helps parents create a coherent narrative that incorporates the profound significance of their child’s life into their own life story, facilitating preservation of their connection and bond to their child. Within the MCGT framework, cognitive schemas and techniques (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Tatrow & Montgomery, 2006) and grief psychoeducation for parents and their primary supporters are incorporated to enhance meaning-making and reframe maladaptive cognitions, facilitating discussion of how to honor the child’s legacy. At the conclusion of each session, parents are presented with “steps for the week,” involving completion of questions they will discuss in the following session. It is recommended that parents will prepare their responses in writing in advance of the next session, as our research has shown that directed writing can assist with prolonged grief symptoms (Lichtenthal & Cruess, 2010). However, we understand this is not realistic for many parents, and provide ample time for contemplation of the questions in each session.

Theoretical foundation

There are two levels of conceptualization that guide MCGT. First is the focus on addressing challenges to finding meaning, purpose, and identity that many grieving individuals face. As noted above, to address such existential distress, MCGT applies the conceptual model suggested by Frankl (1959/1992) and used in MCP whereby meaning and purpose can be found through connectedness with sources of meaning: those relationships, activities, roles, and experiences that an individual finds most valued and meaningful (Breitbart & Poppito, 2014). These sources of meaning can buoy individuals through times of suffering. Furthermore, connection to meaningful relationships, activities, role, and experiences can provide opportunities to feel more “like themselves,” addressing challenges to their sense of identity. Central to this model is the principle that individuals have the freedom to choose their attitude toward their suffering, and that this attitude (i.e., the way they face the adversity before them) can be a source of meaning in and of itself (Breitbart & Poppito, 2014; 1959/1992). MCGT also incorporates principles of meaning reconstruction (Neimeyer, 2001a; Neimeyer, in press), with its tandem emphasis on helping mourners (a) find meaning in the loss and in their lives in its aftermath, and (b) reconstruct a sustaining bond to the deceased to reaffirm attachment security or address unfinished business. This is largely done through experiential exercises that facilitate emotional processing, integration of the loss, and building of distress tolerance.

Over the course of 16 sessions, MCGT systematically touches on each of these different facets of meaning (e.g., sources of meaning, choosing one’s attitude in the face of suffering, sense-making, benefit-finding, posttraumatic growth, legacy), highlighting specific concepts in each session while also weaving in the core principles described above as indicated. The rationale for this approach of examining multiple meaning-related angles stems from our qualitative research with bereaved parents. This work demonstrated that, although various meaning constructs could be distinguished in parents’ narratives, they also had substantial overlap (Lichtenthal et al., 2017). For example, the process of making sense of the loss (sense-making) and their suffering sometimes involved finding a greater positive significance of their pain (benefit-finding) and child’s life (legacy), directing their own personal mission (purpose) in the world post-loss. Such complexities suggest that enhancement of meaning in parents who experience existential and meaning-making challenges can be achieved through various avenues. We have termed this the Reciprocal Pathway Theory of Meaning-making because of the empirical observation that enhancing one domain of meaning may positively impact another (e.g., a bereaved parent’s sense of purpose may be increased through devoting herself to creating meaning in her child’s life and legacy) (Lichtenthal, Applebaum, & Breitbart, 2011a; Lichtenthal & Breitbart, 2015; Lichtenthal et al., 2017; Lichtenthal, Roberts, & Shuk, 2011c). This suggests there are multiple “clinical entry points” through which a therapist can intervene to enhance meaning (Lichtenthal et al., 2011a; Lichtenthal et al., 2011c). Thus, across the 16 sessions, the therapist is working from different vantage points, ensuring that various facets of meaning are considered and explored to the extent they may be helpful for a given parent. The concept of “choice” is highlighted repeatedly to empower parents and highlight freedom in the face of situations that are beyond their control, such as their profound loss. Any resulting enhancement in meaning can be viewed as an intermediary outcome (a construct to be enhanced in its own right), and a mediator, driving improvement in multiple psychosocial outcomes, including PGD symptoms. These improvements may be bidirectional, with reductions in other outcomes in turn resulting in further enhancements in meaning.

The second level of conceptualization examines more specifically MCGT’s hypothesized mechanisms of change. The theoretical foundation is largely informed by the cognitive-behavioral model, which has demonstrated efficacy in improving prolonged grief, mood, and anxiety (Boelen, 2006; Bryant et al., 2017; Tolin, 2010). Meaning reconstruction results in cognitive shifts, including development of an adaptive, coherent perspective of one’s life story as well as adaptive perspectives about specific situations associated with guilt, regret, and anger (Lichtenthal et al., 2017). MCGT assists with reconstructing unhelpful thoughts that may have their origins in preexisting cognitive schemas (e.g., a belief that being emotional is a sign of weakness, or a belief that one is incompetent). These shifts can result in a reduction in negative affect. Engagement with sources of meaning (e.g., relationships, valued activities, experiences) has overlap with behavioral activation and is thus expected to similarly result in positive experiences, cognitions, and affect (Lejuez, Hopko, & Hopko, 2001). Enhancement of such positive outcomes is in turn expected to improve depressive symptoms (Lejuez et al., 2001) and prolonged grief (Boelen & van den Bout, 2002; Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Bonanno, 2010).

MCGT also draws from attachment theory (Bowlby, 1978), continuing bonds theory, and the cognitive attachment model of prolonged grief (Maccallum & Bryant, 2013). The caregiver role commonly remains active after death (Bowlby, 1978), and so MCGT provides opportunities for parents to continue to engage in acts of nurturance and care for the child. As the parent is gradually transforming the relationship through consideration of new ways of connecting, the continued bond to the child offers presence as an antidote to the sense of absence (Field, Gal-Oz, & Bonanno, 2003). This preserves some structure of self-identity, but as suggested by the cognitive attachment model (Maccallum & Bryant, 2013), MCGT facilitates consideration of unique aspects of the griever’s identity that are not “merged” with the deceased (Maccallum & Bryant, 2013). The intervention supports accessing of autobiographical memory information to develop a coherent life story that includes the deceased as part of the parent’s past, supports ways of connecting in the present, and helps with envisioning a future in which the child is not physically present. In sum, through structured exercises and discussion, MCGT helps parents transform the caregiving role in a manner that preserves the relationship with their deceased child and aspects of their identity new, adaptive, and meaningful ways (Bowlby, 1978; Ronen et al., 2009), while simultaneously supporting development of future goals and an identity that is independent of the deceased child (Maccallum & Bryant, 2013).

Measures

Demographic, medical, and mental health background information was collected at T1. All other outcomes described were assessed at T1, T2, T3, and T4. The primary outcome was PGD symptoms as measured by the widely used, validated 13-item PG-13 (Prigerson et al., 2009a). The PG-13 assesses the frequency of 4 grief-related symptoms in the past month and the severity of 7 current grief-related symptoms using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Additional items evaluate symptom duration and functional impairment. Scores range from 11 to 55, with high scores representing elevated PGD symptoms (Prigerson et al., 2009a).

Sense of meaning was an intermediary outcome, assessed by the Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R), a valid multidimensional measure with 48 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (Reker, 1992). The LAP-R has six subscales, including Purpose, Coherence, Choice/Responsibleness, Death Acceptance, Existential Vacuum, and Goal Seeking. This study focused on the Personal Meaning Index (PMI), which is a composite of the Purpose and Coherence subscales reflecting having life goals, a sense of direction, and an integrated understanding of oneself and the world (Reker, 1992). Scores on the PMI range from 16 to 112, with higher scores reflecting a greater sense of personal meaning in life. The LAP-R has high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.77 to 0.91 (Reker, 1992). Meaning was also measured using a single item from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL) that asks participants to complete the statement, “Over the past two (2) days, my life has been,” using a response scale ranging from 0 (utterly meaningless and without purpose) to 10 (very purposeful and meaningful) (Cohen et al., 1997). Another facet of meaning is posttraumatic growth, which reflects positive byproducts of the loss experience and was assessed with the reliable, validated 21-item Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI). The PTGI has six subscales, each reflecting a different content area of growth that an individual may have experienced as a result of adversity faced: Relating to Others, New Possibilities, Personal Strength, Spiritual Change, and Appreciation of Life. Scores on these subscales as well as a total score reflect higher levels of posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). The degree to which parents experienced a continued connection with their child was measured by the validated, reliable Continuing Bonds Scale (CBS), an 11-item measure (Field et al., 2003). Responses are rated using a Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very true), yielding a total score ranging from 11 to 55.

Several secondary outcomes were evaluated as well. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R), a 20-item reliable self-rated measure (Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, 2002; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). Responses range from 0 (not at all or less than one day) to 4 (nearly every day for 2 weeks), with higher scores reflecting worse symptoms of depression. Hopelessness was assessed by the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), a well-validated 20-item true-false measure of participants’ degree of pessimism and hopelessness, with scores ranging from 0 to 20 (Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974). State and trait anxiety was assessed with the 40-item, validated and reliable State-Trait Anxiety Scale (Spielberger, 1983). Twenty items assess emotional states experienced in the present moment, while the remaining items assess how the respondent generally feels. Responses range from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always), with higher scores reflecting increased anxiety (Spielberger, 1983). Positive and negative affect were evaluated using the widely used, validated 20-item measure Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), asking participants to evaluate their positive affect and negative affect on the day of completion (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Items are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely), with higher scores reflecting higher levels of positive or negative emotion. We evaluated health-related quality of life with the RAND 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), a reliable and valid 36-item instrument that assesses eight domains of health, including physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems, role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, energy/fatigue, and general health perceptions (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). Higher scores on the SF-36 reflect more positive health (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992).

We evaluated therapeutic alliance with the Working Alliance Inventory-Short Form (WAI-SF; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989), a 12-item multidimensional validated scale that was given to participants at T2 and T3. Acceptability was measured at T3 a Post-Intervention Questionnaire that measured the most and least helpful treatment components and assessed satisfaction with treatment length.

Data Analysis

To characterize preliminary feasibility and acceptability, descriptive statistics of postintervention questionnaire ratings, rates of recruitment, reasons for refusal, attrition, and number of sessions were calculated. To characterize preliminary treatment effects, Cohen’s d for change scores was calculated as a measure of effect size, relative to baseline, for pairwise-complete data at each longitudinal timepoint.

Results

Participant characteristics

Background data were available for the 8 of 11 participants who initiated MCGT sessions. Participants were primarily female (75%), white, non-Hispanic (88%) and college educated (76%). The age of participants ranged from 36 to 65 with a mean of 49.4 years (SD = 10.8). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants who received MCGT in-person did not differ statistically from those receiving the videoconference format on baseline or longitudinal measures, including the PG-13, LAP-R PMI, or the CBS (all ps > 0.10). Longitudinal trends were also visually compared and appeared comparable between groups. Data from both open trials were therefore compiled in our presentation and discussion of the study findings.

Table 1.

Participant Background Characteristics

| Characteristic | Group | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 36 – 41 | 4 (50%) |

| 58 – 65 | 4 (50%) | |

| Gender | Female | 6 (75%) |

| Male | 2 (25%) | |

| Race | White, not Hispanic | 7 (88%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (13%) | |

| Education (years) | 12 or less | 2 (25%) |

| 16 | 3 (38%) | |

| More than 16 | 3 (38%) | |

| Employment | Full-Time | 4 (50%) |

| Part-Time | 2 (25%) | |

| Unemployed or Homemaker |

2 (25%) | |

| Religion | Catholic | 7 (88%) |

| Jewish | 1 (13%) | |

| Do you consider yourself a spiritual person? | Somewhat | 4 (50%) |

| Yes, very much | 4 (50%) | |

| Do you consider yourself a religious person? | Somewhat | 7 (88%) |

| Yes, very much | 1 (13%) | |

| Any counseling or treatment for emotional problem in past? | Yes | 6 (75%) |

| No | 2 (25%) | |

| Do you have any other children? | Yes | 6 (75%) |

| No | 2 (25%) |

Note. Descriptive statistics for the 8 participants for whom baseline data were available. Mean age was 49.4 years (SD = 10.8), with a range of 36 – 65 years.

Feasibility, acceptability, and therapeutic alliance

We examined the proportion of patients approached who consented, the proportion approached who declined participation, reasons for refusal, and the proportion approached who were ineligible. In total, 78 parents were approached for the study. Twenty-two (28%) were unreachable, and 21 (27%) were ineligible (3 because non-English speaking, 10 because of geography, 8 because PG-13 scores did not meet the threshold). Twenty (26%) parents declined, with reasons for refusal including it being too painful (n = 4), coping satisfactorily (n = 4), geographical barriers (n = 3), time barriers (n = 3), study not applicable to parent (n = 3), prior negative experience in research (n = 1), and no reason given (n = 2). Thirteen of the 56 (23%) parents reached were eligible and expressed interest, and 2 of 13 (15%) were lost to follow-up before enrolled.

Eleven participants combined enrolled in the open trials. Of the six participants who enrolled in the in-person open trial, four (67%) completed the treatment protocol. One participant dropped out prior to completing the T1 assessment, and one participant dropped following the eighth MCGT session, prior to completing the T2 assessment. Both participants dropped out because of difficulty traveling to the hospital for sessions. Of the five participants in the videoconferencing open trial, two (40%) completed all 16 sessions. Two parents dropped after screening, but prior to T1. One parent did so because of increased demands at work, and the other was provided with a tablet for videoconferencing by our group, but had difficulty with Internet access and expressed it was time to “move on” from the hospital. One participant dropped out after completion of nine MCGT sessions and was lost to follow-up.

Of the eight participants who started sessions, six (75%) completed all 16 sessions. Across both open trials, 11 participants completed screening data, 8 participants provided T1 data, 7 participants provided T2 data, and 6 participants completed T3 data. Acceptability was evaluated with a Post-Intervention Questionnaire. All participants provided positive feedback about how MCGT helped them and found the length of the intervention satisfactory. Feedback about the least helpful aspects of MCGT was also provided. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Post-Intervention Survey Responses

| Item | Response | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| How much has/did this treatment focus(ed) on providing support to you? | Quite a bit | 2 (33%) |

| Very much | 4 (67%) | |

| How much has/did this treatment focus(ed) on talking about your feelings about your loss? | Somewhat | 1 (17%) |

| Quite a bit | 2 (33%) | |

| Very much | 3 (50%) | |

| How much has/did this treatment focus(ed) on finding a sense of meaning and purpose in life? | Quite a bit | 2 (33%) |

| Very much | 4 (67%) | |

| How would you rate the length of this treatment (please check only one)? |

Just right | 6 (100%) |

| What has/did this treatment help(ed) you with the most? | 1. “To greater appreciate the value in my son’s life. To better understand my value in making his life better-both before + during his illness. To better understand my son’s value in affecting my life. To learn ways to keep my son close to me and to enjoy the feeling. To recognize the strength he gave to me in life and to be able to continue to benefit from that strength. To better recognize the things most important to me, how they’ve changed, and how they’ve always been there, a natural continuity that makes sense to go on in the future. To feel better about myself for what I have done, what I am doing now, and for what I can expect in the future.” | |

| 2. “It helped me find more lighthouses in my life to help me get through the rough times.” | ||

| 3. “It showed me [a] different way to look on the problem. Teached me how to talk about it.” | ||

| 4. “Vocalizing the immense personal pain that I hold inside.” | ||

| 5. “Reconnecting with my son, (child’s name) who died. I realized that I was avoiding thinking of him because it was too painful. Also, reconnecting with my surviving son, (other child’s name)... I feel that our relationship is moving in a positive direction. Although I will never have the meaning back that I had when (child’s name) was alive, I realize that I am on my way to working through my grief and developing new meaning. I have a bit more energy than I did at the beginning of the treatment. Many of the sessions were difficult, yet I know that is when I grow the most.” | ||

| 6. “It got me to write the letter to the doctors that I needed to get done to liberate myself to do other things.” | ||

| What has/did this treatment help(ed) you with the least? | 1. “No least. Check that…winning the lottery…no help at all! :)” | |

| 2. “N/A” | ||

| 3. “I still don’t know how to deal with [the] lost.” | ||

| 4. “The emphasis on Viktor Frankl, I personally didn’t need for perspective.” | ||

| 5. [No response] | ||

| 6. [No response] | ||

Note. Six participants provided post-intervention responses. Each number listed next to the two openended question responses corresponds to a single participant (e.g., Participant 1, 2, 3, etc.).

Therapeutic alliance as measured by the WAI was also evaluated at T2 (M = 76.4, SD = 8.3; n = 7) and T3 (M = 78.0, SD = 10.8; n = 6). The WAI Total Scores were comparable (p > 0.78) for the in-person participants (T2 M = 75.75; T3 M = 77.00) and videoconferencing (T2 M = 77.33; T3 M = 80.00).

Preliminary evidence for treatment efficacy

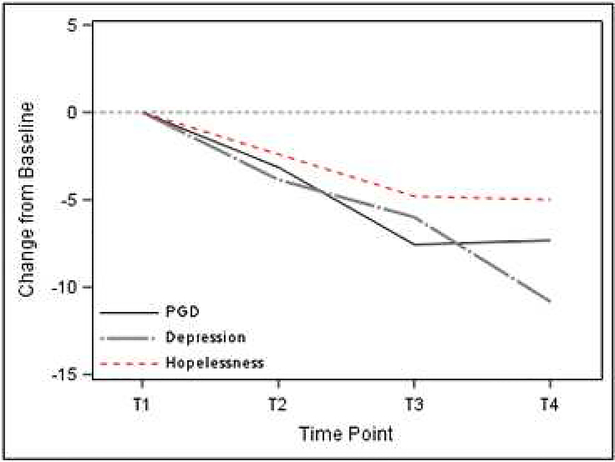

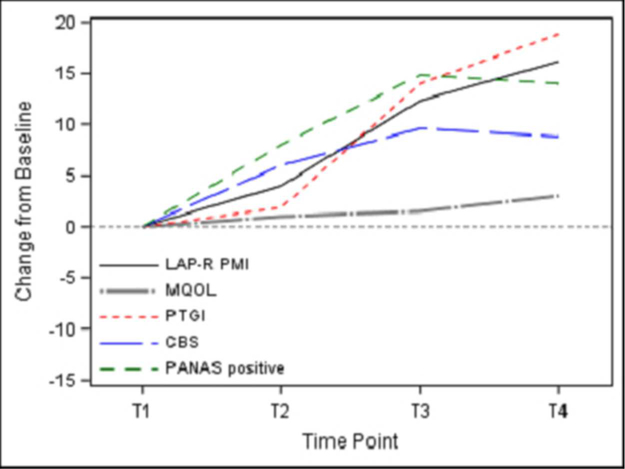

Numerous score improvements were observed from baseline to post-intervention, many of which were maintained through the three-month follow-up assessment. See Table 3 for baseline descriptive statistics and Table 4 for longitudinal change scores and effect size estimates. Large post-treatment (T3) intervention effects (Cohen’s d ≥ 0.80) were observed on the PG-13, LAP-R PMI, MQOL meaning item, CESD-R, BHS, CBS, PTGI total, and PANAS Positive Affect measures. Moderate post-treatment intervention effects (0.50 ≤ d < 0.80) were observed in the MOS Energy/Fatigue, Emotional Well-being, Social Functioning, Pain, and General Health subscales. At the three-month follow-up assessment, effects were generally maintained for the PG13, LAP-R PMI, MQOL meaning item, BHS, and CBS. Effects were even stronger at three months for the CESD-R, PTGI total and subscales, and MOS Social Functioning, and General Health. Efficacy results were inconsistent or conflicting for STAI State and Trait, as well as MOS Physical Functioning and Role Limitations Due to Emotional Problems. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the change over time observed in several outcomes.

Table 3.

Participant Baseline Measures

| Measure | Mean (SD) | Min - Max | Measure | Mean (SD) | Min - Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG-13 | 39.50 (6.1) | 30 – 49 | CESD-R | 24.00 (8.8) | 10 – 40 |

| LAP-R PMI | 49.50 (17.9) | 17 – 79 | BHS | 12.43 (7.0) | 0 – 19 |

| LAP-R Purpose | 23.75 (10.3) | 9 – 44 | STAI Trait | 38.75 (4.9) | 33 – 49 |

| LAP-R Coherence | 25.75 (8.7) | 8 – 35 | STAI State | 42.38 (4.4) | 36 – 48 |

| LAP-R Choice/Responsibleness | 35.38 (6.3) | 26 – 45 | PANAS Positive | 17.00 (7.3) | 4 – 26 |

| LAP-R Death Acceptance | 38.63 (5.2) | 31 – 46 | PANAS Negative | 16.14 (6.8) | 10 – 30 |

| LAP-R Existential Vacuum | 35.20 (6.8) | 24 – 43 | SF-36 Physical Functioning | 92.15 (6.4) | 83.3 – 100 |

| LAP-R Goal Seeking | 31.38 (8.3) | 16 – 45 | SF-36 Role Limitations – Physical | 75.00 (46.3) | 0 – 100 |

| LAP-R Existential Trans. | 56.93 (21.0) | 32 – 89 | SF-36 Role Limitations - Emotional | 33.33 (35.6) | 0 – 100 |

| MQOL Meaning | 4.25 (1.8) | 1 – 7 | SF-36 Energy/ Fatigue | 26.88 (17.3) | 5 – 50 |

| PTGI Total | 57.63 (9.6) | 47 – 77 | SF-36 Emotional Well-being | 40.00 (15.3) | 12 – 64 |

| PTGI Relating to Others | 24.00 (2.6) | 20 – 28 | SF-36 Social Functioning | 56.25 (28.4) | 12.5 – 100 |

| PTGI New Possibilities | 8.63 (4.2) | 5 – 17 | SF-36 Pain | 80.31 (18.4) | 47.5 – 100 |

| PTGI Personal Strength | 11.63 (3.3) | 6 – 17 | SF-36 General Health | 53.75 (30.0) | 15 – 100 |

| PTGI Spiritual Change | 5.25 (3.1) | 2 – 10 | |||

| PTGI Appreciation of Life | 8.13 (2.9) | 3 – 12 | |||

| CBS | 33.00 (8.7) | 17 – 41 |

Note. SD = Standard deviation. PG-13 = Prolonged Grief-13. LAP-R = Life Attitude Profile-Revised. PMI = Personal Meaning Index. MQOL = McGill Quality of Life. PTGI = Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. CBS = Continuing Bonds Scale. CESD-R = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised. BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale. STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Survey. T2 = Mid-intervention. T3 = Post-intervention. T4 = 3 months post-intervention.

Table 4.

Changes in Prolonged Grief Symptoms, Meaning, and Continuing Bonds from Baseline through Follow-up

| T2 | T3 | T4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Measures | Diff (SD) | d | DIff (SD) | d | Diff (SD) | d |

| PG-13 | −3.14 (3.0) | −1.06 | −8.17 (4.8) | −1.70 | −7.33 (5.8) | −1.26 |

| LAP-R PMI | 4.00 (7.5) | 0.53 | 12.33 (5.9) | 2.11 | 16.17 (12.3) | 1.32 |

| LAP-R Purpose | 2.86 (2.7) | 1.07 | 5.17 (3.4) | 1.53 | 9.17 (7.7) | 1.19 |

| LAP-R Coherence | 1.14 (5.1) | 0.22 | 7.17 (3.1) | 2.29 | 7.00 (5.6) | 1.25 |

| LAP-R Choice/Responsibleness | 3.14 (2.9) | 1.08 | 4.33 (1.4) | 3.17 | 4.67 (7.9) | 0.59 |

| LAP-R Death Acceptance | −0.29 (6.0) | −0.05 | −0.50 (4.5) | −0.11 | 0.33 (5.8) | 0.06 |

| LAP-R Existential Vacuum | −3.94 (6.2) | −0.64 | −4.43 (3.8) | −1.17 | −8.43 (2.8) | −2.98 |

| LAP-R Goal Seeking | 1.71 (6.0) | 0.29 | 5.67 (1.2) | 4.68 | 3.57 (6.5) | 0.55 |

| LAP-R Existential Trans. | 9.08 (7.5) | 1.21 | 14.93 (9.7) | 1.54 | 26.02 (16.9) | 1.54 |

| MQOL Meaning Item | 0.57 (1.4) | 0.41 | 2.50 (1.5) | 1.65 | 3.17 (2.3) | 1.37 |

| PTGI Total | 1.86 (12.5) | 0.15 | 14.00 (12.4) | 1.13 | 18.83 (8.8) | 2.15 |

| PTGI Relating to Others | −0.71 (1.4) | −0.52 | 5.33 (4.5) | 1.18 | 4.50 (2.2) | 2.08 |

| PTGI New Possibilities | 1.71 (3.4) | 0.51 | 4.67 (3.5) | 1.33 | 5.50 (2.8) | 1.96 |

| PTGI Personal Strength | 0.29 (4.9) | 0.06 | 2.17 (3.6) | 0.60 | 5.33 (3.8) | 1.39 |

| PTGI Spiritual Change | −0.57 (3.7) | −0.15 | 0.67 (2.3) | 0.29 | 0.67 (1.5) | 0.44 |

| PTGI Appreciation of Life | 1.14 (2.4) | 0.47 | 1.17 (2.3) | 0.50 | 2.83 (2.7) | 1.04 |

| CBS | 6.00 (9.0) | 0.67 | 9.60 (7.6) | 1.26 | 8.80 (10.0) | 0.88 |

| Secondary Measures | Diff (SD) | d | DIff (SD) | d | Diff (SD) | d |

| CESD-R | −3.86 (7.4) | −0.52 | −6.00 (7.2) | −0.84 | −10.83 (7.6) | −1.43 |

| BHS | −2.40 (4.3) | −0.55 | −4.80 (4.8) | −1.01 | −5.00 (7.1) | −0.70 |

| STAI Trait Anxiety | −1.00 (4.5) | −0.22 | 1.00 (5.7) | 0.18 | 3.00 (6.0) | 0.50 |

| STAI State Anxiety | −5.00 (5.2) | −0.97 | 1.00 (5.1) | 0.20 | −1.00 (5.0) | −0.20 |

| PANAS Positive Affect | 8.00 (17.2) | 0.46 | 14.83 (15.0) | 0.99 | 14.00 (14.2) | 0.99 |

| PANAS Negative Affect | 4.83 (7.5) | 0.64 | 3.40 (6.5) | 0.52 | 2.80 (4.4) | 0.63 |

| SF-36 Physical Functioning | 1.83 (9.8) | 0.19 | −1.39 (16.7) | −0.08 | 2.78 (9.3) | 0.30 |

| SF-36 Role Limitations – Physical | 0.00 (14.4) | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.0) | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.0) | 0.00 |

| SF-36 Role Limitations - Emotional | 0.00 (19.2) | 0.00 | −11.11 (17.2) | −0.65 | 22.22 (27.2) | 0.82 |

| SF-36 Energy/ Fatigue | 5.00 (16.8) | 0.30 | 14.17 (19.9) | 0.71 | 21.67 (18.3) | 1.18 |

| SF-36 Emotional Well-being | 3.43 (12.1) | 0.28 | 6.67 (12.6) | 0.53 | 13.33 (10.9) | 1.22 |

| SF-36 Social Functioning | −1.79 (16.8) | −0.11 | 12.50 (19.4) | 0.65 | 18.75 (25.9) | 0.72 |

| SF-36 Pain | 1.79 (11.1) | 0.16 | 7.08 (15.5) | 0.46 | 3.75 (14.3) | 0.26 |

| SF-36 General Health | 5.00 (17.1) | 0.29 | 8.33 (14.7) | 0.57 | 13.33 (19.7) | 0.68 |

Note. Measures of change are based on the subset of participants with both a baseline value and the applicable longitudinal timepoint. Cohen’s d reflects the longitudinal gain, such that a positive value indicates an increase and negative value indicates a decrease; optimal direction of change is dependent on the measure. Diff = Mean difference. PG-13 = Prolonged Grief-13. LAP-R = Life Attitude Profile-Revised. PMI = Personal Meaning Index. MQOL = McGill Quality of Life. PTGI = Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. CBS = Continuing Bonds Scale. CESD-R = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised. BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale. STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Survey. T2 = Mid-intervention. T3 = Postintervention. T4 = 3 months post-intervention.

Figure 1. Changes in prolonged grief, depression, and hopelessness over time.

Note. The figure depicts mean change in each measure, at each timepoint, relative to baseline. Pairwise complete data are used to maximize sample size, thus not all participants included for T2 analysis were available for T3 and T4 analysis. For interpretation of size of effects, see individual measure ranges in Table 1. PGD = Prolonged grief symptoms. T1 = Pre-intervention. T2 = Mid-intervention. T3 = Post-intervention. T4 = 3 months post-intervention.

Figure 2. Changes in meaning, growth, continuing bonds and positive affect over time.

Note. The figure depicts mean change in each measure, at each timepoint, relative to baseline. Pairwise complete data are used to maximize sample size, thus not all participants included for T2 analysis were available for T3 and T4 analysis. For interpretation of size of effects, see individual measure ranges in Table 1. LAP-R PMI = Life Attitude Profile-Revised Personal Meaning Index. MQOL = McGill Quality of Life Meaning Item. T1 = Pre-intervention. T2 = Mid-intervention. T3 = Post-intervention. T4 = 3 months post-intervention.

Discussion

The current study offers preliminary evidence of the feasibility, acceptability, and promise of MCGT in improving psychological adjustment in parents who have lost a child to cancer. Participants provided generally positive feedback about the intervention, while also suggesting ways to strengthen the intervention, such as offering additional coping skills and reducing the emphasis on Frankl’s (1959/1992) work. Several participants offered video-recorded testimonials describing the benefits of MCGT that they were told would be used in recruitment of bereaved parents in future phases of this research program. The feasibility of conducting a larger trial MCGT was suggested by adequate retention rates. Seventy-five percent of parents who started MCGT completed all 16 sessions, a rate comparable to those observed in prior psychotherapy trials (Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Geographical barriers to completing sessions in the in-person trial were expected, and explained why 15% of refusers declined participation and why both parents who dropped out of the in-person open trial discontinued participation.

Our prior research with parents bereaved by cancer found that although 87% of parents with elevated PGD symptoms reported they would like assistance with their coping, only approximately half had actually used mental health services (Lichtenthal et al., 2011b). Because bereaved parents face numerous emotional and logistical barriers to accessing support and underutilize available services (Lichtenthal et al., 2011b), we conducted a proof-of-concept pilot delivering MCGT using videoconferencing. Our results demonstrated that delivery of the intervention via videoconferencing was both feasible and acceptable to participants in our sample. These results contribute to the growing literature supporting the utility and effectiveness of telemental health approaches (Aboujaoude, Salame, & Naim, 2015; Fletcher et al., 2018; Frueh et al., 2007; Germain, Marchand, Bouchard, Guay, & Drouin, 2009; Hilty et al., 2013; Langarizadeh et al., 2017; Ruskin et al., 2004). Telemental health interventions can also facilitate continuity of care with the treating institution in bereavement. For bereaved parents, this may be particularly important because of the common wish to remain connected to their child’s treating institution, which can prevent the secondary loss of the healthcare team (D’Agostino, Berlin-Romalis, Jovcevska, & Barrera, 2008; Lichtenthal et al., 2015).

While we found that videoconferencing was a useful way to deliver this grief intervention, the use of telemental health did not eliminate drop-outs from the study. Two participants dropped out prior to initiating MCGT, and one participant dropped out after completing approximately half of the sessions. Although we tried to be very accommodating in scheduling sessions and to directly address the emotional toll of engaging in the study, additional efforts to increase retention should be made in future investigations. Investigators should remain mindful of the practical and emotional challenges of study participation, remaining highly flexible in scheduling and offering substantial support of the completion of all study activities. It was encouraging to see, though, that therapeutic alliance ratings of the in-person and videoconferencing sessions were similar on average. Symptom improvements were also similar. This suggests that videoconferencing can be an effective way of delivering MCGT and is worthy of further examination.

MCGT was designed to enhance bereaved parents’ sense of meaning and to decrease prolonged grief symptom in parents reporting elevated levels of prolonged grief. In our sample, we observed improvements over time on both of these outcomes. The hypothesized theoretical model assumes that enhancement of meaning helps buoy bereaved parents when they feel adrift and are suffering, enhancing their ability to co-exist with their enduring yearning for their child. MCGT targets maladaptive PGD symptoms, such as identity challenges, bitterness, and a sense of meaninglessness, while promoting acceptance of the loss and reducing disbelief by assisting parents to develop a coherent narrative about the loss and their lives (Lichtenthal et al., 2017). This is consistent with research showing that bereaved parents who are able to accept the loss, maintain a connection to their child and other important relationships, and redefine their sense of identity may be better able to adapt to their loss (Barrera et al., 2009). To address these feelings of absence, MCGT helps parents continue their relationship with their child as a source of meaning, which simultaneously reinforces their sense of identity as their child’s parent (Lichtenthal et al., 2017). In the current study, this was evidenced by increases in scores on the measure of continuing bonds. Participants also reported increases in posttraumatic growth, which has been associated with decreased grief intensity in bereaved parents (Engelkemeyer & Marwit, 2008). Facilitating the process of benefit-finding has previously been shown to result in reductions of prolonged grief, depressive, and posttraumatic growth symptoms (Lichtenthal & Cruess, 2010).

Reductions in depressive symptoms and hopelessness were similarly observed in the current study. Such mood improvements may have been realized through the enhancements in meaning, growth, and positive affect that parents reported at the conclusion of MCGT. These increases may also explain the health-related quality of life benefits we found. Specifically, parents reported improved energy levels, emotional well-being, and social functioning. Improvements in bodily pain and general health were also observed. Increases in mood may have positively influenced perceptions of pain and their physical health. It may also be that decreases in grief intensity led to reductions in the physical manifestations of grief – exhaustion, identification pain, sleep and appetite disturbances – which in turn account for health benefits. We did not observe, however, improvements in physical functioning and health-related functional limitations. MCGT also did not result in consistent improvements is anxiety symptoms. Perhaps reengaging in life brought about new sources of anxiety. We found that negative affect ratings, understood to be orthogonal to positive affect (Watson et al., 1988), increased on average as well. This might reflect decreases in avoidance that are characteristic of PGD, or it might be an artifact of the natural, daily fluctuations of emotion that grieving individuals commonly face (Lichtenthal, in press-a, in press-b). This suggests the value of using multiple, real-time assessments to better understand psychological outcomes in clinical trials (Verhagen, Hasmi, Drukker, van Os, & Delespaul, 2016).

Limitations

As an initial evaluation of MCGT, this smaller-scale study has several methodological limitations. The use of a within-group design without a comparison group limits conclusions about improvements that may be due to the effects of time. Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are regarded as the “gold standard” of intervention research, development of conceptually-sound approaches commonly rely on proof-of-concept pilot trials (Rounsaville et al., 2001). The small, relatively homogeneous sample and use of a single interventionist are also substantial limitations. While this single interventionist design may have improved treatment fidelity, it limits the generalizability of findings. We were also limited by the inherent biases of relying on self-report data and the relatively low enrollment rate, which was due to a combination of, in almost equivalent proportions, difficulty reaching parents, ineligibility, and parents declining.

Future Directions

There has been a long-standing need for interventions to address the intense, often debilitating grief that bereaved parents face. Given bereaved parents’ increased risk for a wide range of poor mental and physical health outcomes (Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2003; Oliver, 1999), the transdiagnostic symptom improvements we observed are encouraging. Future research should compare the efficacy of MCGT in an RCT with a larger, more diverse study sample and multiple study interventionists. The use of blinded assessments would also strengthen the study design. Should MCGT demonstrate efficacy in a larger trial, further investigation of its mechanisms of change and moderators of treatment effects should be conducted.

The long-term goal of this research program is to develop and evaluate MCGT for bereaved individuals to decrease PGD symptoms, increase meaning, and facilitate post-loss adjustment. If MCGT proves efficacious in improving adjustment in parents bereaved by cancer as hypothesized, adaptations for other bereaved populations, such as spouses, adult children, and siblings, can be developed.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the bereaved parents and dedicated staff members who have contributed to this research program. Special thanks to Jacques Barber, PhD, B. Christopher Frueh, PhD, Hayley Pessin, PhD, and Janice Nadeau, PhD. The research referenced has been supported by the National Cancer Institute grants R03CA139944 (Lichtenthal), K07CA172216 (Lichtenthal), P30CA008748 (Thompson), T32CA009461 (Ostroff). This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health (Wiener).

References

- Aboujaoude E, Salame W, & Naim L (2015). Telemental health: A status update. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 223–230. doi: 10.1002/wps.20218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2018). Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, O’Connor K, D’Agostino NM, Spencer L, Nicholas D, Jovcevska V, … Schneiderman G (2009). Early parental adjustment and bereavement after childhood cancer death. Death Stud, 33(6), 497–520. doi: 10.1080/07481180902961153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, & Trexler L (1974). The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol, 42(6), 861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, & Neckelmann D (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res, 52(2), 69–77. doi:S0022399901002963 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA (2006). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Complicated Grief: Theoretical Underpinnings and Case Descriptions. Jan-Feb 2006. Journal of Loss & Trauma,.11(1), pp. [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, & van den Bout J (2002). Positive thinking in bereavement: is it related to depression, anxiety, or grief symptomatology? Psychol Rep, 91(3 Pt 1), 857–863. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.3.857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1978). Attachment theory and its therapeutic implications. Adolesc Psychiatry, 6, 5–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Applebaum AJ, Lichtenthal WG, Li Y, … Fenn N (2018). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: A randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer, 124(15), 3231–3239. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Poppito S, Rosenfeld B, Vickers AJ, Li Y, Abbey J, … Cassileth BR (2012). Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol, 30(12), 1304–1309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, & Poppito SR (2014). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer : a treatment manual. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, Pessin H, Poppito S, Nelson C, … Olden M (2010). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology, 19(1), 21–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Applebaum A, Kulikowski J, & Lichtenthal WG (2015). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy: an effective intervention for improving psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol, 33(7), 749–754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Kenny L, Joscelyne A, Rawson N, Maccallum F, Cahill C, … Nickerson A (2017). Treating Prolonged Grief Disorder: A 2-Year Follow-Up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Psychiatry, 78(9), 1363–1368. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, & Beck AT (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev, 26(1), 17–31. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, & Tong K (1997). Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med, 11(1), 3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino NM, Berlin-Romalis D, Jovcevska V, & Barrera M (2008). Bereaved parents’ perspectives on their needs. Palliative Supportive Care, 6(1), 33–41. 10.1017/S1478951508000060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies R (2004). New understandings of parental grief: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46(5), 506–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03024.xJAN3024 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelkemeyer SM, & Marwit SJ (2008). Posttraumatic growth in bereaved parents. J Trauma Stress, 21(3), 344–346. doi: 10.1002/jts.20338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field NP, Gal-Oz E, & Bonanno GA (2003). Continuing bonds and adjustment at 5 years after the death of a spouse. J Consult Clin Psychol, 71(1), 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher TL, Hogan JB, Keegan F, Davis ML, Wassef M, Day S, & Lindsay JA (2018). Recent Advances in Delivering Mental Health Treatment via Video to Home. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 20(8), 56. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0922-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE (1959/1992). Man’s Search for Meaning (Revised ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Monnier J, Yim E, Grubaugh AL, Hamner MB, & Knapp RG (2007). A randomized trial of telepsychiatry for post-traumatic stress disorder. J Telemed Telecare, 13(3), 142–147. doi: 10.1258/135763307780677604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain V, Marchand A, Bouchard S, Guay S, & Drouin MS (2009). Assessment of the Therapeutic Alliance in Face-to-Face or Videoconference Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2009.0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, & Yellowlees PM (2013). The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health, 19(6), 444–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langarizadeh M, Tabatabaei MS, Tavakol K, Naghipour M, Rostami A, & Moghbeli F (2017). Telemental Health Care, an Effective Alternative to Conventional Mental Care: a Systematic Review. Acta Inform Med, 25(4), 240–246. doi: 10.5455/aim.2017.25.240-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannen PK, Wolfe J, Prigerson HG, Onelov E, & Kreicbergs UC (2008). Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. J Clin Oncol, 26(36), 5870–5876. doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.14.6738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, & Hopko SD (2001). A brief behavioral activation treatment for depression. Treatment manual. Behav Modif, 25(2), 255–286. doi: 10.1177/0145445501252005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Laursen TM, Precht DH, Olsen J, & Mortensen PB (2005). Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(12), 1190–1196. doi:352/12/1190 [pii] 10.1056/NEJMoa033160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Precht DH, Mortensen PB, & Olsen J (2003). Mortality in parents after death of a child in Denmark: a nationwide follow-up study. Lancet, 361(9355), 363–367. doi:S0140–6736(03)12387–2 [pii] 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12387-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal W (2011). Using mixed methods data to adapt Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for bereaved parents and breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 20(Suppl. 2), 15. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG (in press-a). Supporting the bereaved in greatest need: We can do better. Palliat Support Care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG (in press-b). When those who need it most use it least: Facilitating grief support for those at greatest risk. Grief Matters: The Australian Journal of Grief and Bereavement, 21(1), 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Applebaum A, & Breitbart W (2011a). Using mixed methods data to adapt Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for bereaved parents. Paper presented at the International Psycho-Oncology Society 13th World Congress, Antalya, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, & Breitbart W (2015). The central role of meaning in adjustment to the loss of a child to cancer: implications for the development of meaning-centered grief therapy. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care, 9(1), 46–51. doi: 10.1097/spc.0000000000000117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, & Cruess DG (2010). Effects of directed written disclosure on grief and distress symptoms among bereaved individuals. Death Stud, 34(6), 475–499. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2010.483332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA, & Keesee NJ (2010). Sense and significance: a mixed methods examination of meaning making after the loss of one’s child. J Clin Psychol, 66(7), 791–812. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Lacey S, Roberts K, Sweeney C, & Slivjak E (2017). Meaning-Centered Grief Therapy In Breitbart WS (Ed.), Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy in the Cancer Setting (pp. 88–99). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Roberts K, Bohn T, & Farberov T (2011b). Barriers to mental health service use among parents who lost a child to cancer. Paper presented at the American Psychosocial Oncology Society Annual Meeting, Anaheim, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Roberts K, & Shuk E (2011c). Meaning in parents bereaved by cancer: A mixed methods study. Paper presented at the Association of Death Education and Counseling 33rd Annual Conference, Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Sweeney CR, Roberts KE, Corner GW, Donovan LA, Prigerson HG, & Wiener L (2015). Bereavement Follow-Up After the Death of a Child as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 62 Suppl 5, S834–869. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccallum F, & Bryant RA (2013). A Cognitive Attachment Model of prolonged grief: integrating attachments, memory, and identity. Clin Psychol Rev, 33(6), 713–727. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon CJ, Smith NG, Henry M, Milman E, Chochinov HM, Korner A, … Cohen SR (2015). Reconstructing Meaning with Others in Loss: A Feasibility Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Bereavement Group. Death Stud, 39(7), 411–421. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2014.958628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA (2000). Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies, 24(6), 541–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA (2001a). Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss (1st ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA (2001b). Reauthoring life narratives: grief therapy as meaning reconstruction. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci, 38(3–4), 171–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA (in press). Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Stud. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver LE (1999). Effects of a child’s death on the marital relationship: A review. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 39(3), 197–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell TE, & Bonanno GA (2010). Prospective predictors of positive emotions following spousal loss. Psychol Aging, 25(3), 653–660. doi: 10.1037/a0018870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, … Maciejewski PK (2009a). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine, 6(8), e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, … Maciejewski PK (2009b). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med, 6(8), e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA (1986). Parental Loss of a Child. Champaign, IL: Research Press Co. [Google Scholar]

- Reker GT (1992). Manual of the Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R). Trent University, Peterborough, ON: Student Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen R, Packman W, Field NP, Davies B, Kramer R, & Long JK (2009). The relationship between grief adjustment and continuing bonds for parents who have lost a child. Omega (Westport), 60(1), 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin PE, Silver-Aylaian M, Kling MA, Reed SA, Bradham DD, Hebel JR, … Hauser P (2004). Treatment outcomes in depression: comparison of remote treatment through telepsychiatry to in-person treatment. Am J Psychiatry, 161(8), 1471–1476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1471161/8/1471 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Revised). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, & Schut H (2001). Meaning making in the dual process model of coping with bereavement In Neimeyer RA (Ed.), Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss (pp. 55–73). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, & Greenberg RP (2012). Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol, 80(4), 547–559. doi: 10.1037/a0028226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatrow K, & Montgomery GH (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med, 29(1), 17–27. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, & Calhoun LG (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress, 9(3), 455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF (2010). Is cognitive-behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies? A metaanalytic review. Clin Psychol Rev, 30(6), 710–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey TJ, & Kokotovic AM (1989). Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 1, 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen SJ, Hasmi L, Drukker M, van Os J, & Delespaul PA (2016). Use of the experience sampling method in the context of clinical trials. Evid Based Ment Health, 19(3), 86–89. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2016-102418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr., & Sherbourne CD (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care, 30(6), 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol, 54(6), 1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler I (1993). The role of meaning and purpose in life in bereaved parents associated with a self-help group: Compassionate friends. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 28(4), 261271. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler I (2001). Parental bereavement: The crisis of meaning. Death Stud, 25(1), 51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, & Snaith RP (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 67(6), 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]