Abstract

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an insulin secretagogue which is elevated after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB). However, its contribution to glucose metabolism after RYGB remains uncertain.

Aims:

We tested the hypothesis that GLP-1 lowers postprandial glucose concentrations and improves β-cell function after RYGB.

Materials and Methods:

To address these questions we used a labelled mixed meal to assess glucose metabolism and islet function in 12 obese subjects with type 2 diabetes studied before and four weeks after RYGB. During the post-RYGB study subjects were randomly assigned to receive an infusion of either saline or Exendin-9,39 a competitive antagonist of GLP-1 at its receptor. Exendin-9,39 was infused at 300pmol/kg/min for six hours. All subjects underwent RYGB for medically-complicated obesity.

Results.

Exendin-9,39 resulted in increased integrated incremental postprandial glucose concentrations (181 ± 154 vs. 582 ± 129 mmol per 6h, p=0.02). In contrast, this was unchanged in the presence of saline (275±88 vs. 315±66 mmol per 6h, p=0.56) after RYGB. Exendin-9,39 also impaired β-cell responsivity to glucose but did not alter Disposition Index (DI).

Conclusions.

These data indicate that the elevated GLP-1 concentrations that occur early after RYGB improve postprandial glucose tolerance by enhancing postprandial insulin secretion.

1.0. Introduction

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) is commonly performed and can result in remission of type 2 diabetes [1]. This seems to be contingent on the duration and severity of the disease prior to the procedure [2] as β-cell function seems to be relatively unchanged by RYGB [3], in some but not all [4], studies. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) has been posited as a hormonal mediator of diabetes remission, since postprandial GLP-1 concentrations markedly increase after RYGB [5] and infusion or injection of GLP-1 enhances insulin secretion and suppresses glucagon release [6]. The possibility that RYGB might improve β-cell function compared to other bariatric interventions [4] would suggest that endogenous GLP-1 is an important contributor to the changes in glucose metabolism that occur in people with type 2 diabetes after RYGB.

Caloric restriction similar to that experienced early after RYGB also improves glucose metabolism in subjects with type 2 diabetes [7] and is associated with decreased hepatocellular fat, increased hepatic insulin sensitivity and decreased fasting endogenous glucose production (EGP) [8, 9]. An improvement in β-cell function [7] occurs notwithstanding postprandial GLP-1 concentrations far lower than those observed after RYGB [10]. Jorgensen et al. utilized Exendin-9,39, a competitive antagonist of GLP-1 at its receptor, to block the effects of endogenous GLP-1 after RYGB [11] concluding that GLP-1 is important to the remission of type 2 diabetes. However, this study contrasts with other studies utilizing Exendin-9,39 in post-RYGB subjects which resulted in modest effects on postprandial glucose and insulin concentrations [12, 13]. More recently, Vetter et al. reported that identical weight loss with and without RYGB had similar effects on glucose metabolism independently of GLP-1 [14]. However, it is possible that early in the post-operative course after RYGB, GLP-1 may have an effect on β-cell function which is difficult to discern from the effects of caloric restriction in the first months after surgery [7].

We undertook the present series of experiments to examine the effects of endogenous GLP-1 secretion on glucose metabolism four weeks after RYGB in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes [12, 15]. Subjects were studied on two occasions. The first study occurred on the day prior to bariatric surgery while the second occurred four weeks after surgery. During the study performed prior to surgery all subjects received a saline infusion. After surgery, subjects were randomized to receive either saline (Saline → Saline) or Exendin-9,39 (Saline → Exendin-9,39). We report that while blockade of the GLP-1 receptor with Exendin-9,39, impairs insulin secretion and decreases β-cell responsivity it did not alter postprandial glucose turnover. We conclude that elevated postprandial GLP-1 concentrations seen after RYGB slightly, but significantly, enhance β-cell responsivity to glucose after surgery.

2.0. Research Design and Methods

2.1. Subjects

After approval from the Mayo Institutional Review Board, twelve subjects with type 2 diabetes (treated with metformin alone or in combination with a sulfonylurea) undergoing RYGB gave written, informed consent to participate in the study. All subjects had no microvascular complications, were at a stable weight and did not engage in regular exercise. They were instructed to follow a weight maintenance diet (~55% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 15% protein) prior to the first study and instructed to stop glucose-lowering medication three weeks prior to study. During this period subjects self-monitored fasting glucose concentrations twice daily and were instructed to contact the study team in the event of hyperglycemia (≥ 11mmol/l) or polyuria and polydipsia. This did not occur in any of the subjects. Body composition was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DPX scanner; Lunar, Madison, WI).

2.2. Experimental Design

Subjects were studied on two occasions four weeks apart. On the first occasion (Pre-RYGB study) subjects were studied on the day prior to RYGB. Saline was infused from 0 to 360 minutes of the study (see below). On the second occasion subjects were studied 4 weeks after RYGB. At that time subjects were randomized to either receive Exendin-9,39 (1200 pmol/kg bolus followed by infusion at 300pmol/kg/min [16]) referred to as the Saline → Exendin-9,39 group, or saline, referred to as the Saline → Saline group. The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov. Identifier: NCT01843855.

On either occasion subjects were admitted to the CRU at 1700 on the evening prior to study. Subsequently, they consumed a standardized low calorie meal (10 Kcal/Kg body weight: 40% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 30% protein) tolerable to patients who have undergone restrictive upper gastrointestinal procedures and then fasted overnight. At 0630 on the following morning (−180 minutes), a forearm vein was cannulated (18g needle) to allow infusions to be performed. An 18g cannula was inserted retrogradely into a vein on the dorsum of the contralateral hand. This was placed in a heated Plexiglas box maintained at 55°C to allow sampling of arterialized venous blood. A primed (12mg/kg) continuous (0.12mg/kg/min) infusion of [6,6-2H2] glucose was initiated. At time 0 (0930), while sitting in a recliner, subjects consumed a meal (220Kcal, 56% carbohydrate, 25% fat, 19% protein) consisting of 1 scrambled egg, 15g of Canadian bacon, 100ml of water and Jell-O containing 35g of glucose labeled with [1-13C] glucose – (4% enrichment). Consumption of the test meal is standardized as previously described [12]. Simultaneously, Exendin-9,39 or saline was infused. An infusion of [6-3H] glucose was also started, and the infusion rate varied to mimic the anticipated appearance of meal [1-13C] glucose. The rate of infusion of [6,6-2H2] glucose was altered to approximate the anticipated fall in EGP thereby minimizing changes in specific activity [17, 18].

2.3. Analytical techniques

Plasma samples were placed on ice, centrifuged at 4°C, separated, and stored at −20°C until assayed. Glucose concentrations were measured using a glucose oxidase method (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma insulin was measured using a chemiluminescence assay (Access Assay; Beckman, Chaska, MN). Plasma glucagon and C-peptide were measured by Radio-Immunoassay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Collection tubes for GLP-1 had 100 μM of DPP-4 inhibitor added. Total GLP-1 concentrations were measured using a C-terminal assay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Plasma [6,6-2H2] glucose and [1-13C] glucose enrichments were measured using gas chromatographic mass spectrometry (Thermoquest, San Jose, CA) to simultaneously monitor the C-1 and C-2 and C-3 to C-6 fragments, as described previously [19]. In addition, [6-3H] glucose specific activity was measured by liquid scintillation counting following deproteinization and passage over anion and cation exchange columns [18].

2.4. Calculations

The systemic rates of meal appearance (Meal Ra), EGP and glucose disappearance (Rd) were calculated using Steele’s model [20]. Meal Ra was calculated by multiplying rate of appearance of [1-13C] glucose (obtained from the infusion rate of [6-3H] glucose and the clamped plasma ratio of [6-3H] glucose and [1-13C] glucose) by the meal enrichment. EGP was calculated from the infusion rate of [6,62H2] glucose and the ratio of [6,62H2] glucose to endogenous glucose concentrations. Rd was calculated by subtracting the change in glucose mass from the overall rate of glucose appearance as previously described [21, 22]. Values from −30 to 0 minutes were averaged and considered as basal. Area above basal (AAB) was calculated using the trapezoidal rule to calculate Area Under the Curve (AUC) and then subtracting basal AUC [23].

Insulin action (Si) was measured using the oral minimal model. β-Cell responsivity was estimated using the oral C-peptide minimal model, incorporating age-associated changes in C-peptide kinetics [24]. The model assumes that insulin secretion comprises static (φs) and dynamic (φd) components with total β-cell responsivity to glucose (Φ) derived from these two components [15]. Disposition indices (DI) were subsequently calculated by multiplying Φ by Si. We also used the Oral GLP-1 model [25], which assumes that GLP-1 stimulates above-basal but not basal insulin secretion [26], to quantify the potentiation of insulin secretion by endogenous GLP-1 after RYGB. The model also assumes that above-basal insulin secretion is linearly modulated by GLP-1 through an index π, which quantifies the increase of above-basal insulin secretion due to a 1 pmol/L increase in circulating GLP-1 concentrations.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as Mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. To quantify between-group differences for the change from baseline over time, we used (symmetric) percent change [27] calculated as 100*Loge (Present value / Baseline value). Between-group differences were tested using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Within- group differences (pre-RYGB vs. post-RYGB) were compared using a paired, two-tailed t-test. Statistical analyses used Primer 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.0. Results

3.1. Volunteer Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1:

Anthropometric characteristics of the participants in each group, before and after RYGB.

| Saline → Exendin-9,39 | Saline → Saline | *P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Exendin- 9,39 |

Baseline | Saline | ||

| Sex (M / F) | 2 / 5 | 1 / 4 | |||

| Age (Years) | 54 ± 2 | 51 ± 6 | 0.34 | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 6.9 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 0.58 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 116 ± 10 | 104 ± 9 | 136 ± 11 | 125 ± 10 | 0.09 |

| **p = 4.6 × 10−5 | **p = 0.005 | ||||

| Lean Body Mass (kg) | 56 ± 5 | 51 ± 4 | 66 ± 7 | 60 ± 5 | 0.22 |

| **p = 1.4 × 10−5 | **p = 0.006 | ||||

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/l) | 8.9 ± 1.1 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 0.09 |

| **p = 0.01 | **p = 0.01 | ||||

| Fasting Insulin (pmol/l) | 75 ± 13 | 37 ± 10 | 94 ± 10 | 58 ± 8 | 0.23 |

| **p = 0.003 | **P = 0.03 | ||||

| Fasting C-peptide (nmol/l) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.05 |

| **p = 0.001 | **p = 0.006 | ||||

| Fasting Glucagon (ng/l) | 73 ± 6 | 60 ± 3 | 65 ± 5 | 65 ± 6 | 0.05 |

| **p = 0.01 | **p = 0.93 | ||||

Represents the value of an unpaired, two-tailed t-test for between-group differences in symmetrical percent change for a given parameter.

Represents the value of a paired, two-tailed t-test for within-group differences for a given parameter.

Of the twelve subjects who completed the study, 7 received Exendin-9,39 during the second study (Saline→Exendin-9,39) and 5 received saline (Saline→Saline). Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Gender, age, HbA1c, BMI and weight did not differ between groups before surgery and subjects lost a comparable amount of weight after surgery

3.2. Total GLP-1 concentrations before and After RYGB (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Total GLP-1 concentrations in the Saline → Exendin-9,39 (left panels) and the Saline → Saline (right panels) group pre-RYGB + Saline (○) and post-RYGB + Exendin-9,39 (●) or post-RYGB + Saline (◆).

Fasting total GLP-1 concentrations were unchanged post-surgery. However, RYGB, increased postprandial peak and integrated total GLP-1 concentrations. As previously observed [12], Exendin-9,39 infusion increased peak concentrations compared to the group receiving saline (112 ± 14 vs. 52 ± 17 pmol/l, p = 0.03).

3.3. Glucose, Insulin, C-peptide and Glucagon before and After RYGB (Figure 2, Table 1)

Figure 2:

Glucose, Insulin, C-peptide and glucagon concentrations in the Saline → Exendin-9,39 (left panels) and the Saline → Saline (right panels) group pre-RYGB + Saline (○) and post-RYGB + Exendin-9,39 (●) or post-RYGB + Saline (◆).

RYGB (Upper Panels) lowered fasting glucose concentrations in both groups (Table 1). The postprandial peak incremental increase in glucose concentrations also did not differ between groups. The symmetrical percent change in peak postprandial glucose concentrations (pre-RYGB vs. post-RYGB) did not differ between groups (p > 0.05). Integrated glucose concentrations calculated as Area Above Basal (AAB) were increased by RYGB in the presence of Exendin-9,39 (181 ± 154 vs. 582 ± 129 mmol per 6h, p = 0.02) but unchanged with saline (275 ± 88 vs. 315 ± 66 mmol per 6h, p = 0.62). However, the symmetrical percent change in AAB glucose (pre-RYGB vs. post-RYGB) did not differ between groups (p = 0.08).

Fasting insulin concentrations (Upper Middle Panels) were significantly lowered by RYGB in both groups (Table 1). Peak insulin concentrations after RYGB were unchanged in the Saline→Exendin-9,39 (281 ± 45 vs. 255 ± 49 pmol/l, p = 0.59) but increased in the Saline→Saline group (213 ± 82 vs. 522 ± 81 pmol/l, p = 0.007). The symmetrical percent change in peak postprandial insulin concentrations (pre-RYGB vs. post-RYGB) also differed between groups (p < 0.05).

Fasting and postprandial C-peptide concentrations (Lower Middle Panels) reflected the changes in insulin concentrations observed in both groups although there was a proportionately greater decrease in fasting C-peptide in the Saline→Exendin-9,39 group (Table 1). The symmetrical percent change in peak postprandial C-peptide concentrations also differed between groups (p = 0.05).

Fasting glucagon concentrations (Lower Panels) decreased from baseline after RYGB in the Saline→Exendin-9,39 but not in the Saline→Saline group (Table 1). On the other hand, the symmetrical percent change in peak (p = 0.85) and incremental (p = 0.88) postprandial glucagon concentrations did not differ between groups.

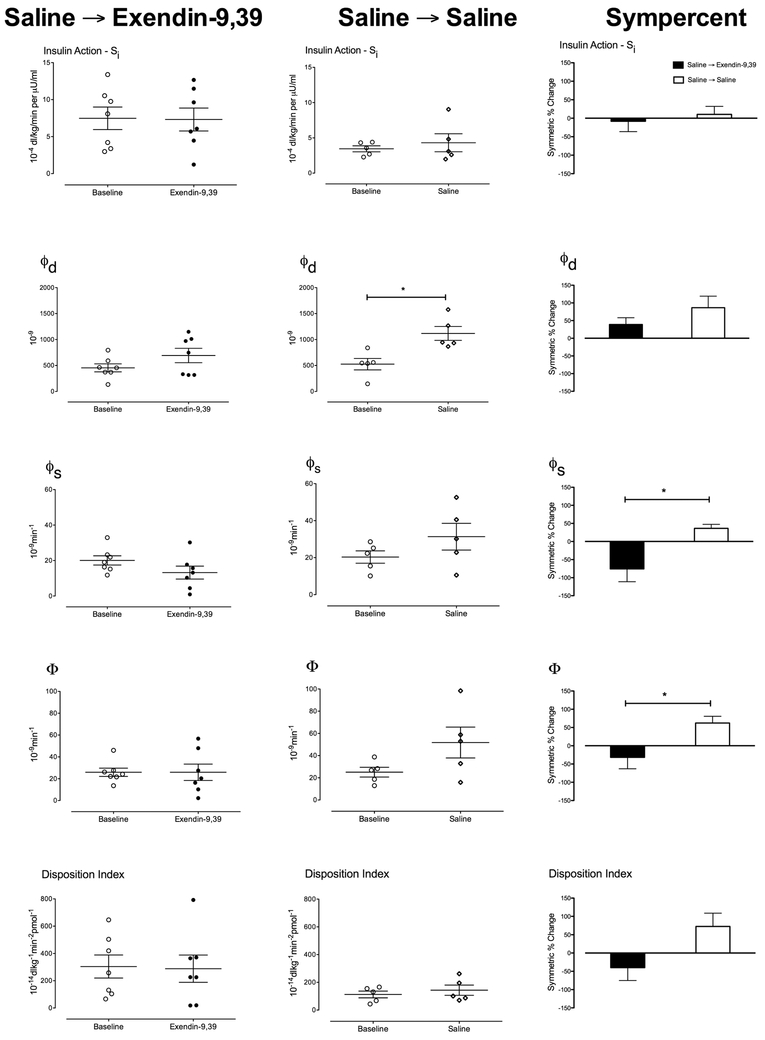

3.4. Insulin action (Si), Dynamic β-cell responsivity (φd, Static β-cell responsivity (φs, Total β-cell responsivity (Φ) and Disposition Index (DI) before and after RYGB (Figure 3, Table 2)

Figure 3:

Insulin action (Si), dynamic (φd). static (φs,) and total (Φ) β-cell responsivity to glucose as well as Disposition Index, in the Saline → Exendin-9,39 group and the Saline → Saline group pre-RYGB + Saline (○) and post-RYGB + Exendin-9,39 (●) or post-RYGB + Saline (◆). The third column shows Symmetrical percent change for each study arm. * denotes p < 0.05.

Table 2:

Indices of insulin secretion and action of the participants in each group, before and after RYGB.

| Saline → Exendin-9,39 | Saline → Saline | *P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Exendin- 9,39 |

Baseline | Saline | ||

| Si (10−4 dl/kg/min per μU/ml) | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ±0.4 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 0.64 |

| **p = 0.93 | **p = 0.46 | ||||

| φdynamic (10−9) | 455 ± 77 | 692 ± 138 | 526 ± 111 | 1118 ± 134 | 0.21 |

| **p = 0.09 | **p = 0.02 | ||||

| φstatic (10−9 min−1) | 20 ± 3 | 13 ± 4 | 20 ± 3 | 31 ± 7 | 0.03 |

| **p = 0.7 | **p = 0.07 | ||||

| Φ (10−9 min−1) | 26 ± 0.04 | 26 ± 8 | 25 ± 4 | 52 ± 14 | 0.04 |

| **p = 1.0 | **p = 0.09 | ||||

| DI (10−14 dl/kg/min per pmol/l) | 304 ± 84 | 288 ± 100 | 132 ± 31 | 402 ± 225 | 0.06 |

| **p = 0.81 | **p = 0.28 | ||||

Represents the value of an unpaired, two-tailed t-test for between-group differences in symmetrical percent change for a given parameter.

Represents the value of a paired, two-tailed t-test for within-group differences for a given parameter.

Insulin action (Upper Panels) was unchanged by RYGB in both groups. The dynamic component of β-cell responsivity (φd-Upper Middle Panels) was significantly increased (p = 0.02) by RYGB in the Saline→Saline group (Table 2). The symmetrical percent change in φd did not differ between groups. On the other hand, while the static component of β-cell responsivity (φs – Middle Panels) was not significantly changed by Exendin-9,39 infusion after RYGB, there was a tendency for this to increase after RYGB in the Saline→Saline group so that the symmetric percent change differed significantly between the two groups (Table 2).

Total β-cell responsivity (Φ – Lower Middle Panels) was unchanged by RYGB in the Saline→Exendin-9,39 and slightly, but not significantly, increased after RYGB in the Saline→Saline group. This was borne out by the symmetric percent change which differed (p=0.04) between groups (Table 2).

However, DI (Lower Panels) which expresses Φ as a function of insulin action was unchanged by RYGB in the Saline→Exendin-9,39. Although there was a tendency for DI to increase in the Saline→Saline group, this difference was not significant. Similarly, the symmetric percent change in DI did not differ between groups (Table 2).

3.5. GLP-1-induced Potentiation of Insulin Secretion (Figure 4)

Figure 4:

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-induced potentiation of post-prandial insulin secretion (π) in the presence of Saline (open bars) and Exendin-9,39 (solid bars). * denotes p < 0.05.

The oral GLP-1 model demonstrated that after RYGB, infusion of Exendin-9,39 inhibited the stimulatory effects of endogenous GLP-1 on insulin secretion as compared to saline (0.7 ± 0.3 vs. 11.0 ± 2.9 % per pmol/l, p = 0.02).

3.6. Endogenous Glucose Production, Meal Appearance and Glucose Disappearance before and after RYGB (Figure 5)

Figure 5:

Endogenous glucose production, rate of systemic meal appearance and glucose disappearance in the Saline → Exendin-9,39 and the Saline → Saline group pre-RYGB + Saline (○) and post-RYGB + Exendin-9,39 (●) or post-RYGB + Saline (◆).

Post-RYGB, fasting EGP decreased (p < 0.05) in both the Saline→Exendin-9,39 (18.4 ± 1.1 vs. 13.9 ± 1.3 μmol/kg/min) and the Saline→Saline (17.8 ± 2.4 vs. 14.1 ± 1.7 μmol/kg/min) groups (Upper Panels). Nadir postprandial suppression of EGP was unchanged (p > 0.05) by RYGB in both groups. The symmetric percent change in fasting and nadir EGP did not differ between groups.

As expected given the alteration in upper gastrointestinal anatomy, peak Meal Ra increased post-RYGB in both groups (Middle Panels). The timing of this peak did not differ in either group. The symmetric percent change in peak Meal Ra did not differ between groups. AAB meal appearance (Meal Ra) was not altered by RYGB in either group.

Post-RYGB, fasting glucose disappearance decreased (p < 0.01) in both the Saline→Exendin-9,39 (20 ± 1.1 vs. 16.2 ± 1.3 μmol/kg/min) and the Saline→Saline (20.0 ± 2.3 vs. 15.4 ± 1.9 μmol/kg/min) groups (Lower Panels). In contrast, peak postprandial glucose disappearance was unchanged (61.4 ± 13.0 vs. 78.1 ± 13.4 μmol/kg/min, p = 0.41) by RYGB in the Saline→Exendin-9,39 group but increased (47.2 ± 11.4 vs. 78.4 ± 11.4 μmol/kg/min, p = 0.05) in the Saline→Saline group. However, the symmetric percent change in fasting and peak glucose disappearance did not differ significantly between groups. No within- or between-group differences in integrated (AAB) rates of glucose disappearance were observed.

4.0. Discussion

4 weeks after RYGB, subjects with type 2 diabetes have lower fasting glucose concentrations, explained by decreased rates of fasting endogenous glucose production. The use of a competitive antagonist for GLP-1 at its cognate receptor, Exendin-9,39, results in a small, but significant increase in postprandial glucose excursion. This is explained by a decrease in both peak and integrated postprandial insulin (and C-peptide) concentrations as well as by net β-cell responsivity to glucose (quantified using Φ). Use of the Oral GLP-1 model [25], confirmed the inhibition of GLP-1-induced potentiation of insulin secretion (quantified using π) when Exendin-9.39 is infused at 300pmol/kg/min in keeping with prior data [12].

RYGB results in a substantial reduction in fasting glucose within 4 weeks of surgery despite minimal weight loss. This is due to a decrease in fasting EGP and is also observed when people with type 2 diabetes subjected to equivalent caloric restriction [7]. Since this occurred in the presence of decreased fasting insulin concentrations, it implies an improvement in hepatic insulin action (at least in the fasting state) or a change in the ability of factors other than insulin to regulate glucose production. On the other hand, net postprandial insulin action (quantified by Si) was not altered by RYGB regardless of whether or not GLP-1 action was inhibited by Exendin-9,39. This implies that, as before [12], the effect of Exendin-9,39 to increase incremental glucose concentrations is primarily explained by decreased insulin secretion.

Impaired GLP-1-induced potentiation of insulin secretion resulted in a decrease in β-cell response to sustained hyperglycemia (φs), consistent with prior reports of the mechanism by which GLP-1 and GLP-1-based therapy alter insulin secretion [12, 18]. This implies that the elevated GLP-1 concentrations observed after RYGB increases static β-cell responsivity (φs) thought to be equivalent to the 2nd phase of insulin secretion [15]. Consistent with prior observations, Exendin-9,39 did not alter dynamic β-cell responsivity (φd) thought to be equivalent to the 1st phase of insulin secretion [15]. This implies that GLP-1 concentrations post-RYGB do not measurably alter the size of the immediately releasable pool of insulin [12]. Since this accumulates during fasting it is also possible that a lack of effect of Exendin-9,39 on φd may be an artefact of the experimental design where GLP-1 receptor blockade is initiated at the start of the meal.

Meal appearance represents the net result of intestinal absorption and splanchnic extraction of the ingested meal [28]. Given that integrated meal appearance did not differ from pre-RYGB values, this implies that postprandial GLP-1 concentrations do not affect these parameters in the post-RYGB setting and that in the presence of permissive insulin concentrations splanchnic extraction of ingested carbohydrate is primarily driven by postprandial glucose concentrations [29].

RYGB is associated with a paradoxical increase in postprandial glucagon concentrations – as observed in this experiment, in both the presence or absence of Exendin-9,39. Inhibition of GLP-1 actions by Exendin-9,39 resulted in a non-significant trend to higher postprandial concentrations, suggesting a weak inhibitory effect of endogenous GLP-1 on glucagon secretion after RYGB as observed previously [11, 12]. The role and contribution of postprandial glucagon concentrations to EGP and overall glucose metabolism in RYGB will require further study.

In the current experiment, RYGB did not alter net postprandial insulin action (quantified by Si), despite effects on fasting EGP. This contrasts with a recent experiment where a small improvement in insulin action, measured with an intravenous glucose tolerance test, twenty-one days after RYGB was noted. However, the effect of RYGB was smaller than that produced by caloric restriction alone [30]. In addition, using the same methodology we used in this experiment, we have reported that insulin action post-RYGB did not differ from that observed in age- and weight-matched controls [12]. Nevertheless, it is possible that our study was underpowered to detect a small effect of RYGB on insulin action in the early postoperative phase.

The dose required to completely inhibit GLP-1 action in humans is unknown. We infused Exendin-9,39 at 300 pmol/kg/min. Based on prior experiments [31-33] and the estimated portal concentrations of GLP-1 [34], this rate should result in near complete inhibition of GLP-1 actions at its cognate receptor [35]. Nevertheless, it is possible that the inhibition of GLP-1 was incomplete in the current experiment and therefore the effect of endogenous GLP-1 on insulin secretion underestimated. Indeed, π calculated using the Oral GLP-1 model ≠ 0. However, we have previously demonstrated that the effect of this infusion rate on glucose concentrations [12] was similar to those observed with much higher infusion rates of Exendin-9,39 [11, 13].

The increase in GLP-1 concentrations after GLP-1 receptor blockade by exendin-9,39 has been observed previously [12]. Conversely, elevated concentrations of intact GLP-1 in the presence of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition decreases total GLP-1 concentrations [17, 36, 37]. These observations imply that the L-cell are responsive to circulating concentrations of active GLP-1 [36] but the mechanism by which this occurs is unclear.

Despite the negative effect of Exendin-9,39 on postprandial insulin secretion and on β-cell responsivity to glucose, the net effect on postprandial glucose metabolism was small. Indeed EGP suppressed to the same nadir regardless of the presence or absence of Exendin-9,39. Similarly, Meal appearance was not significantly affected. The relative lack of effect of a decrease in β-cell function on postprandial glucose concentrations emphasizes the importance of glucose effectiveness in the maintenance of postprandial glucose homeostasis. Since glucose effectiveness is impaired in people with type 2 diabetes; [38] this may perhaps explain why we observed a slightly greater effect of Exendin-9,39 on net glucose concentrations in this experiment compared to our prior observations in non-diabetic subjects [12]. Our study suffers from two limitations. The first is that the blood volume requirements precluded studying all subjects twice in the post-operative period (once with saline infusion and once with Exendin-9,39). The second is the relatively small numbers of subjects studied making the results vulnerable to differences in baseline characteristics and the inherent variability of the individual parameters measured. Nevertheless, our results are compatible with previous findings [12] and are supported by the oral GLP-1 model [25] which confirms the inhibitory action of Exendin-9,39 on GLP-1-induced insulin secretion.

In summary, like caloric restriction, RYGB results in a decrease in fasting glucose concentrations in subjects with type 2 diabetes. This is primarily due to decreased fasting rates of endogenous glucose production. Exendin-9,39, four weeks after surgery, inhibits endogenous GLP-1 action and results in a small, but significant, increase in incremental glucose concentrations due to decreased β-cell responsivity to glucose. Increased postprandial GLP-1 secretion cannot explain all of the metabolic changes observed after RYGB but contributes to postprandial β-cell function after RYGB in people with type 2 diabetes.

Highlights.

GLP-1 receptor blockade 4 weeks after gastric bypass raises postprandial glucose

This is because blockade impairs post-prandial β-cell responsiveness to glucose

The postprandial suppression of glucose production is independent of GLP-1

GLP-1 secretion does not explain all of the metabolic changes observed after RYGB

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The authors acknowledge the support of the Mayo Clinic General Clinical Research Center (DK TR000135). This work was supported by NIH DK78646 and by DK82396 (Dr. Vella).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Vella is the recipient of an investigator-initiated grant from Novo Nordisk. He has consulted for Bayer and vTv Therapeutics. None of the other authors have relevant disclosures.

Clinical Trial: NCT01843855

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Vella is the recipient of an investigator-initiated grant from Novo Nordisk. He has consulted for Bayer and vTv Therapeutics. None of the other authors have relevant disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2004;292:1724–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Still CD, Wood GC, Benotti P, Petrick AT, Gabrielsen J, Strodel WE, et al. Preoperative prediction of type 2 diabetes remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2014;2:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nguyen KT, Billington CJ, Vella A, Wang Q, Ahmed L, Bantle JP, et al. Preserved Insulin Secretory Capacity and Weight Loss Are the Predominant Predictors of Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Randomized to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Diabetes. 2015;64:3104–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kashyap SR, Bhatt DL, Wolski K, Watanabe RM, Abdul-Ghani M, Abood B, et al. Metabolic Effects of Bariatric Surgery in Patients With Moderate Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: Analysis of a randomized control trial comparing surgery with intensive medical treatment. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kellum JM, Kuemmerle JF, O'Dorisio TM, Rayford P, Martin D, Engle K, et al. Gastrointestinal hormone responses to meals before and after gastric bypass and vertical banded gastroplasty. Annals of Surgery. 1990;211:763–70; discussion 70-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kieffer TJ. Gastro-intestinal hormones GIP and GLP-1. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2004;65:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sathananthan M, Shah M, Edens KL, Grothe KB, Piccinini F, Farrugia LP, et al. Six and 12 Weeks of Caloric Restriction Increases beta Cell Function and Lowers Fasting and Postprandial Glucose Concentrations in People with Type 2 Diabetes. J Nutr. 2015;145:2046–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kelley DE, Wing R, Buonocore C, Sturis J, Polonsky K, Fitzsimmons M. Relative effects of calorie restriction and weight loss in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Taylor R. Type 2 diabetes: etiology and reversibility. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1047–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Laferrere B, Teixeira J, McGinty J, Tran H, Egger JR, Colarusso A, et al. Effect of weight loss by gastric bypass surgery versus hypocaloric diet on glucose and incretin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jorgensen NB, Dirksen C, Bojsen-Moller KN, Jacobsen SH, Worm D, Hansen DL, et al. The exaggerated glucagon-like peptide-1 response is important for the improved beta-cell function and glucose tolerance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:3044–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shah M, Law JH, Micheletto F, Sathananthan M, Dalla Man C, Cobelli C, et al. Contribution of endogenous glucagon-like peptide 1 to glucose metabolism after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetes. 2014;63:483–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jimenez A, Casamitjana R, Viaplana-Masclans J, Lacy A, Vidal J. GLP-1 Action and Glucose Tolerance in Subjects With Remission of Type 2 Diabetes After Gastric Bypass Surgery. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2062–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vetter ML, Wadden TA, Teff KL, Khan ZF, Carvajal R, Ritter S, et al. GLP-1 plays a limited role in improved glycemia shortly after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a comparison with intensive lifestyle modification. Diabetes. 2015;64:434–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cobelli C, Dalla Man C, Toffolo G, Basu R, Vella A, Rizza R. The oral minimal model method. Diabetes. 2014;63:1203–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sathananthan M, Farrugia LP, Miles JM, Piccinini F, Dalla Man C, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Direct Effects of Exendin-(9,39) and GLP-1-(9,36)amide on Insulin Action, beta-Cell Function, and Glucose Metabolism in Nondiabetic Subjects. Diabetes. 2013;62:2752–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bock G, Dalla Man C, Micheletto F, Basu R, Giesler PD, Laugen J, et al. The effect of DPP-4 inhibition with sitagliptin on incretin secretion and on fasting and postprandial glucose turnover in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73:189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dalla Man C, Bock G, Giesler PD, Serra DB, Ligueros Saylan M, Foley JE, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition by vildagliptin and the effect on insulin secretion and action in response to meal ingestion in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:14–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Beylot M, Previs SF, David F, Brunengraber H. Determination of the 13C-labeling pattern of glucose by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1993;212:526–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Steele R, Bjerknes C, Rathgeb I, Altszuler N. Glucose uptake and production during the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes. 1968;17:415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rizza RA, Toffolo G, Cobelli C. Accurate Measurement of Postprandial Glucose Turnover: Why Is It Difficult and How Can It Be Done (Relatively) Simply? Diabetes. 2016;65:1133–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vella A, Rizza RA. Application of isotopic techniques using constant specific activity or enrichment to the study of carbohydrate metabolism. Diabetes. 2009;58:2168–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Smushkin G, Sathananthan M, Piccinini F, Dalla Man C, Law JH, Cobelli C, et al. The effect of a bile acid sequestrant on glucose metabolism in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:1094–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Van Cauter E, Mestrez F, Sturis J, Polonsky KS. Estimation of insulin secretion rates from C-peptide levels. Comparison of individual and standard kinetic parameters for C-peptide clearance. Diabetes. 1992;41:368–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dalla Man C, Micheletto F, Sathananthan M, Vella A, Cobelli C. Model-Based Quantification of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-Induced Potentiation of Insulin Secretion in Response to a Mixed Meal Challenge. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dalla Man C, Micheletto F, Sathananthan A, Rizza RA, Vella A, Cobelli C. A model of GLP-1 action on insulin secretion in nondiabetic subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E1115–E21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cole TJ. Sympercents: symmetric percentage differences on the 100 log(e) scale simplify the presentation of log transformed data. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19:3109–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vella A, Shah P, Basu R, Basu A, Camilleri M, Schwenk WF, et al. Effect of enteral vs. parenteral glucose delivery on initial splanchnic glucose uptake in nondiabetic humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cherrington AD, Stevenson RW, Steiner KE, Davis MA, Myers SR, Adkins BA, et al. Insulin, glucagon, and glucose as regulators of hepatic glucose uptake and production in vivo. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1987;3:307–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jackness C, Karmally W, Febres G, Conwell IM, Ahmed L, Bessler M, et al. Very Low Calorie Diet mimics the early beneficial effect of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on insulin Sensitivity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes. 2013;62:3027–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schirra J, Nicolaus M, Roggel R, Katschinski M, Storr M, Woerle HJ, et al. Endogenous glucagon-like peptide 1 controls endocrine pancreatic secretion and antro-pyloro-duodenal motility in humans. Gut. 2006;55:243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schirra J, Nicolaus M, Woerle HJ, Struckmeier C, Katschinski M, Goke B. GLP-1 regulates gastroduodenal motility involving cholinergic pathways. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:609–18, e21-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schirra J, Sturm K, Leicht P, Arnold R, Goke B, Katschinski M. Exendin(9-39)amide is an antagonist of glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1421–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ionut V, Liberty IF, Hucking K, Lottati M, Stefanovski D, Zheng D, et al. Exogenously imposed postprandial-like rises in systemic glucose and GLP-1 do not produce an incretin effect, suggesting an indirect mechanism of GLP-1 action. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2006;291:E779–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Edwards CM, Todd JF, Mahmoudi M, Wang Z, Wang RM, Ghatei MA, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 has a physiological role in the control of postprandial glucose in humans: studies with the antagonist exendin 9-39. Diabetes. 1999;48:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Deacon CF, Wamberg S, Bie P, Hughes TE, Holst JJ. Preservation of active incretin hormones by inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV suppresses meal-induced incretin secretion in dogs. J Endocrinol. 2002;172:355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Herman GA, Bergman A, Stevens C, Kotey P, Yi B, Zhao P, et al. Effect of single oral doses of sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, on incretin and plasma glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Basu A, Caumo A, Bettini F, Gelisio A, Alzaid A, Cobelli C, et al. Impaired basal glucose effectiveness in NIDDM: contribution of defects in glucose disappearance and production, measured using an optimized minimal model independent protocol. Diabetes. 1997;46:421–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]