Abstract

Background:

Cancer beliefs and perceptions of cancer risk affect the cancer continuum. Identifying underlying factors associated with these beliefs and perceptions in Texas can help inform and target prevention efforts.

Methods:

We developed a cancer-focused questionnaire and administered it online to a nonprobability sample of the Texas population. Weighted multivariable logistic regression analysis identified key factors associated with perceptions and beliefs about cancer.

Results:

The study population comprised 2034 respondents (median age, 44.4 years) of diverse ethnicity: 45.5% were non-Hispanic white, 10.6% non-Hispanic black, and 35.7% Hispanic. Self-reported depression was significantly associated with cancer risk perceptions and cancer beliefs. Those indicating frequent and infrequent depression versus no depression were more likely to believe that: (i) compared to other people their age, they were more likely to get cancer in their lifetime (OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 1.95–4.39 and OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.17–2.74, respectively); and (ii) when they think about cancer, they automatically think about death (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.56–2.69 and OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.11–1.92, respectively). Frequent depression versus no depression was also associated with agreement that (i) it seems like everything causes cancer (OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.26–2.22) and (ii) there is not much one can do to lower one’s chance of getting cancer (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.09–1.89). Other predictors for perceived cancer risk and/or cancer beliefs were sex, age, ethnicity/race, being born in the US, marital status, income, body mass index, and smoking.

Conclusions:

We identified depression and other predictors associated with cancer risk perceptions and beliefs in Texas.

Impact:

Increased attention to reducing depression may improve cancer risk perceptions and beliefs.

Keywords: Cancer, beliefs, survey, Texas, disparities

Introduction

Texas ranks third in the United States for cancer prevalence and mortality, with 121,463 new cancer cases and 44,713 cancer deaths predicted for 2018 (1,2). In line with the overall US, the five cancers with highest incidence in Texas are breast, prostate, lung, colorectal, and uterine cancers (2). As modifiable and extrinsic risk factors contribute substantially to each of these malignancies, increased effort in primary cancer prevention is warranted to help combat the rising economic burden of cancer in the state (3,4).

Texas has rich racial and ethnic diversity, being comprised of 43.4% non-Hispanic whites (NHWs), 38.6% Hispanics of any race, 11.9% non-Hispanic blacks (NHBs), and 4.4% Asians (5). It is home to the second largest population of African Americans in the US and is projected to be a Hispanic-majority state by 2022; furthermore, half of people 65 years and older are predicted to belong to a racial or ethnic minority group by 2038 (6). These shifting demographics would be expected to alter the population’s cancer risk perceptions and beliefs.

In many health behavior theories, perceptions of one’s disease risk is an important predictor of intentions and behavior to avoid risk (7). An underlying assumption in these theories is that people who believe they are at increased risk (“compared to other people your age, how likely are you to get cancer in your lifetime?”) are more likely to engage in health behaviors that will lessen their risk.

Beliefs about the role of one’s behavior in enhancing cancer risk (“cancer is most often caused by a person’s behavior or lifestyle”) have been associated with knowledge and self-efficacy (8–10). Thus, although health-adverse behaviors/lifestyle choices are known to increase the risk for many cancers, there is insufficient awareness on or belief about the cancer risks associated with many such factors, including obesity, poor diet, and lack of physical activity (11–13). This is unfortunate, as about 42% of cancer cases may be preventable by lifestyle modification (14). Whereas improved educational strategies and dissemination of lifestyle risk information is needed, it is also important to recognize that deliberate avoidance of health information is relatively common in the US (15). Such behavior can serve as a mechanism to maintain hope or denial, resist overexposure to repetitive messaging, and avoid interference with preferred lifestyle choices and activities. Also, unwillingness to know health risks (e.g. “I’d rather not know my chance of getting cancer”) typically occurs in those who lack personal or interpersonal resources to cope with such information (16) Importantly, avoidance of cancer risk information is known to vary by demographics and psychosocial attributes, and avoidance has been associated with lower uptake of colon cancer screening (17).

It is well established that an individual’s beliefs can play a central role in health behavior (18,19), and fatalistic beliefs have been described across the cancer prevention, screening, and survivorship domains. Fatalistic beliefs represent powerlessness to change the future and submission to events that are perceived as inevitable (20). Fatalistic beliefs about cancer prevention include pessimism (“it seems like everything causes cancer”) and helplessness (“there’s not much you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer”“)(9). Individuals who hold such fatalistic beliefs are more likely to have lower levels of engagement in preventive behaviors and have greater preference for avoidance of cancer risk information (9,17,21). Moreover, a cancer diagnosis is frequently linked with belief in inevitable death (“when I think about cancer, I automatically think about death”) and this can create barriers to healthcare-seeking behaviors as individuals with low self-efficacy attempt to delay confronting such threats (22). Of increasing importance to Texas, fatalistic beliefs about cancer are particularly prevalent among both NHBs and Hispanics, and this matter requires careful consideration when optimizing preventive interventions (8,9,23).

Specific knowledge of current cancer risk perceptions and beliefs held by the racially and ethnically diverse Texas population is critical to help inform and target future prevention and control efforts. Thus, we conducted an online survey of more than 2000 Texas residents to uncover factors underlying health beliefs and shed light on current barriers to cancer prevention behavior across the state.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures

A nonprobability sample of adult Texas residents was identified among online research panelists retained by Qualtrics. The company used IP addresses to monitor Texas residency and ensure each respondent completed only one survey. Goals were set for strata by sex (50% male and 50% female), ethnicity/race (34% Hispanic/Latinos, 36% NHWs, 25% NHBs, and 5% Asian/other), annual household income (48% < $50,000, 30% $50,000-$99,999, and 22% ≥ $100,000), and locale (60% urban and 40% rural). Based on state demographics, intentional oversampling of NHBs was performed to increase robustness of data for this subgroup (5). Unless affirming Mexican, Hispanic, or Latino ethnicity, those selecting white as the sole race were assigned to the NHW category and those selecting black/African American either alone or with other races were assigned to the NHB category. Strata for household income was based on current data for the state (24). Urban-rural locale was determined by matching respondents’ ZIP codes to county and county to rural/urban designations using freely available resources (25,26).

The Texas health screening questionnaire was piloted (n = 50) to test for any technical issues and estimate time to completion before full launch on February 5 through March 5, 2018. The questionnaire was administered in English and Mexican Spanish, with translation performed by MasterWord Services Inc (Houston, TX). Assessment of the first 1600 completed questionnaires showed that sampling targets were mostly met for Hispanics, females, lower income categories, and urban residents. To increase ascertainment from rural areas, target strata were loosened to complete required sample size in a timely manner. The final study sample comprised 2050 complete responses. Participants received $10 compensation or its equivalent through the Qualtrics’ online survey platform. The study was approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board (PA16–0724).

Measures

The overall Texas health screening survey drew on national instruments to assess cancer beliefs, risk behaviors, and screening and prevention practices across the state (27–29). The primary outcomes analyzed herein focus on perceived risk of cancer and cancer beliefs, with all six questions previously validated by the Health Information National Trends Survey, HINTS (29).

Outcome measures:

A single measure assessed perceived cancer risk: 1) Compared to other people your age, how likely are you to get cancer in your lifetime? The five possible responses were: very likely, likely, neither likely or unlikely, unlikely, and very unlikely. Five measures assessed cancer beliefs: 1) It seems like everything causes cancer, 2) There’s not much you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer, 3) Cancer is most often caused by a person’s behavior or lifestyle, 4) I’d rather not know my chance of getting cancer, and 5) When I think about cancer, I automatically think about death. The four possible responses were: strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree.

Key predictors:

Outcome measures were correlated with standard demographic and socioeconomic factors including sex, age, ethnicity/race, country of origin, education, marital status, total household size, employment status, annual household income, and home ownership. In addition, we hypothesized that health-adverse behaviors such as smoking and chronic conditions such as depression, diabetes, and obesity may play a role in risk perceptions and beliefs, and these predictors were included in the analysis.

Body mass index:

Respondents’ body mass index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported weight and height and grouped based on WHO classification (30). Individuals were categorized as underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI = 18.5 to < 25.0), overweight (BMI = 25.0 to < 30.0), or obese (class I, BMI = 30.0 to < 35.0; class II, BMI = 35.0 to < 40.0; class III, BMI ≥ 40.0).

Smoking:

Smoking status was determined using two questions. Respondents were first asked, “Have you ever smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Those answering “no” were characterized as never smokers. Those answering “yes” were asked, “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” Those answering “not at all” were classified as former smokers and those answering “every day” or “some days” were classified as current smokers.

Diabetes:

Diabetes was determined by asking all participants regardless of sex, “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had/have: diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Response options included yes, no, and borderline.

Depression:

Self-reported depression was assessed by asking, “How often do you feel depressed?” Response options included daily, weekly, monthly, a few times a year, and never. Depression was classified as frequent if respondents selected daily, weekly, or monthly and infrequent if selecting a few times a year.

Statistical analysis

Following a data quality check to identify outliers (e.g. height, weight), the final dataset included 2034 respondents. The study sample was calibrated against state demographics by ICF International, Inc (Fairfax, Virginia), using the 2015 5-year American Community Survey-Texas. Weights for the dataset were calculated using a three-dimensional raking approach and iterative post-stratification using: sex; three-category age (18–44, 45–59, and ≥ 60 years); and four-category race/ethnicity (NHW, NHB, Hispanic, and other) (31). Descriptive statistics were calculated using R package “survey.” Multivariable survey logistic regression with survey weights was performed using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC (SAS for Windows, version 9.4) to examine factors associated with perceived cancer risk and cancer beliefs. Likert scale responses were collapsed into positive and negative categories. For cancer risk perceptions (five-point response scale), the neutral response “neither likely or unlikely” was excluded from the analysis. The other four responses were grouped into very likely/likely and unlikely/very unlikely (reference group). Response options for the cancer beliefs questions (four-point response scale) were grouped into strongly agree/somewhat agree and somewhat disagree/strongly disagree (reference group). To assess whether strength of association was noteworthy, we calculated Bayesian false-discovery probabilities (BFDP) (32). In the multiple hypothesis-testing context, BFDP allows the false-discovery rate to be controlled. We calculated the BFDP value using a prior probability of 0.05 for an association. The standard recommended threshold of BFDP < 0.8 was used to declare noteworthy associations.

Results

Demographics

Descriptive data and weighted percentages for the 2034 survey respondents are presented in Table 1. The weighted study sample included 50.8% females and 49.2% males. The weighted mean and median age was 44.4 and 44.0 years, respectively. There were 45.5% NHWs (n = 639), 10.6% NHBs (n = 468), and 35.7% Hispanics (n = 764) of any race. The highest proportion (51.3%) were younger adults 18 to 44 years old and the lowest proportion (14.4%) were older adults 65 years or older. Only 8.2% were born outside the US. A total of 35.9% had completed college or gone on to postgraduate studies, and only 5% had received less than a high school education. About half of the study sample was either married or living as married, and 29.2% had never been married. A total of 50.6% were employed, 10.6% unemployed, and 16.0% retired; only 5.2% were students. More than half of respondents were home owners, and the median household size was two persons. The household annual income distribution included 21.5% below $20,000, 33.4% between $20,000 and $49,999, 20.9% between $50,000 and $74,999, and 24.2% at $75,000 or more. Some level of financial difficulty was reported by 28.5%, and 26.3% reported having no health insurance coverage. Only 1.33% completed the survey in Spanish.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

| Measure | No. (N = 2034) |

%, Weighted |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (N= 2034) | ||

| Female | 1348 | 50.8 |

| Male | 686 | 49.2 |

| Ethnicity/race (N= 2034) | ||

| Hispanic | 764 | 35.7 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 639 | 45.5 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 468 | 10.6 |

| Others | 163 | 8.2 |

| Age (N= 2034) | ||

| 18–44 years | 1267 | 51.3 |

| 45–64 years | 569 | 43.3 |

| 65 years or older | 198 | 14.4 |

| Born In USA (N= 2034) | ||

| No | 178 | 8.2 |

| Yes | 1856 | 91.8 |

| Education (N= 2033) | ||

| Less than 8 years | 21 | 0.8 |

| 8 to 11 years | 93 | 4.2 |

| 12 years or completed high school | 471 | 22.6 |

| Post–high school training other than college (vocational or technical) | 134 | 6.5 |

| Some college | 610 | 29.9 |

| College graduate | 508 | 25.5 |

| Postgraduate | 196 | 10.4 |

| Marital status (N= 2033) | ||

| Divorced | 222 | 11.8 |

| Living as married | 158 | 6.9 |

| Married | 834 | 45.4 |

| Separated | 52 | 2.4 |

| Single, never been married | 696 | 29.2 |

| Widowed | 71 | 4.4 |

| Occupation status (N= 2032) | ||

| Disabled | 122 | 6.7 |

| Homemaker | 214 | 8.8 |

| Retired | 237 | 16.0 |

| Student | 136 | 5.2 |

| Employed | 1050 | 50.6 |

| Unemployed | 228 | 10.6 |

| Other | 45 | 2.2 |

| Rent or own (N= 2031) | ||

| Occupied without paying monetary rent | 199 | 9.0 |

| Own | 1002 | 56.7 |

| Rent | 830 | 34.3 |

| Income range (N= 2034) | ||

| $0 to $9,999 | 212 | 8.7 |

| $10,000 to $14,999 | 140 | 6.4 |

| $15,000 to $19,999 | 138 | 6.4 |

| $20,000 to $34,999 | 335 | 15.8 |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 351 | 17.6 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 404 | 20.9 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 215 | 11.0 |

| $100,000 to $199,999 | 203 | 11.3 |

| $200,000 or more | 36 | 1.9 |

| Which one of these comes closest to your own feelings about your household’s income these days? (N= 2031) | ||

| Finding it very difficult on present income | 190 | 8.7 |

| Finding it difficult on present income | 416 | 19.8 |

| Getting by on present income | 831 | 42.2 |

| Living comfortably on present income | 594 | 29.4 |

| Do you have any kind of health care coverage? (N= 2031) |

||

| No | 598 | 26.3 |

| Yes | 1433 | 73.7 |

Health risk factors of the study sample

Weighted percentages for health risk factors are reported in Table 2. The study sample included 19.2% former smokers and 21.9% current smokers. A total of 39% reported experiencing daily, weekly, or monthly episodes of depression (grouped as frequent depression), and 13.2% had a prior diagnosis of diabetes. The majority of respondents (69.9%) were either overweight or obese, including 10.1% with class III obesity.

Table 2.

Study sample: health risk factors

| Measure | No. | %, Weighted |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking status (N= 2032) | ||

| Never smokers | 1286 | 58.9 |

| Former smokers | 315 | 19.2 |

| Current smokers | 431 | 21.9 |

| Depression (N= 2032) | ||

| Daily | 305 | 14.8 |

| Weekly | 301 | 13.9 |

| Monthly | 217 | 10.3 |

| A few times a year | 615 | 30.4 |

| Never | 594 | 30.7 |

| Diabetes (N= 2032) | ||

| No | 1,646 | 79.5 |

| Borderline | 150 | 7.3 |

| Yes | 236 | 13.2 |

| BMI (N= 2002) | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 63 | 3.0 |

| Normal weight (18.5 to < 25) | 568 | 27.2 |

| Overweight (25 to < 30) | 575 | 30.7 |

| Class I obesity (30 to < 35) | 387 | 19.3 |

| Class II obesity (35 to < 40) | 196 | 9.8 |

| Class III obesity (40 or above) | 213 | 10.1 |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Risk perceptions and beliefs about cancer

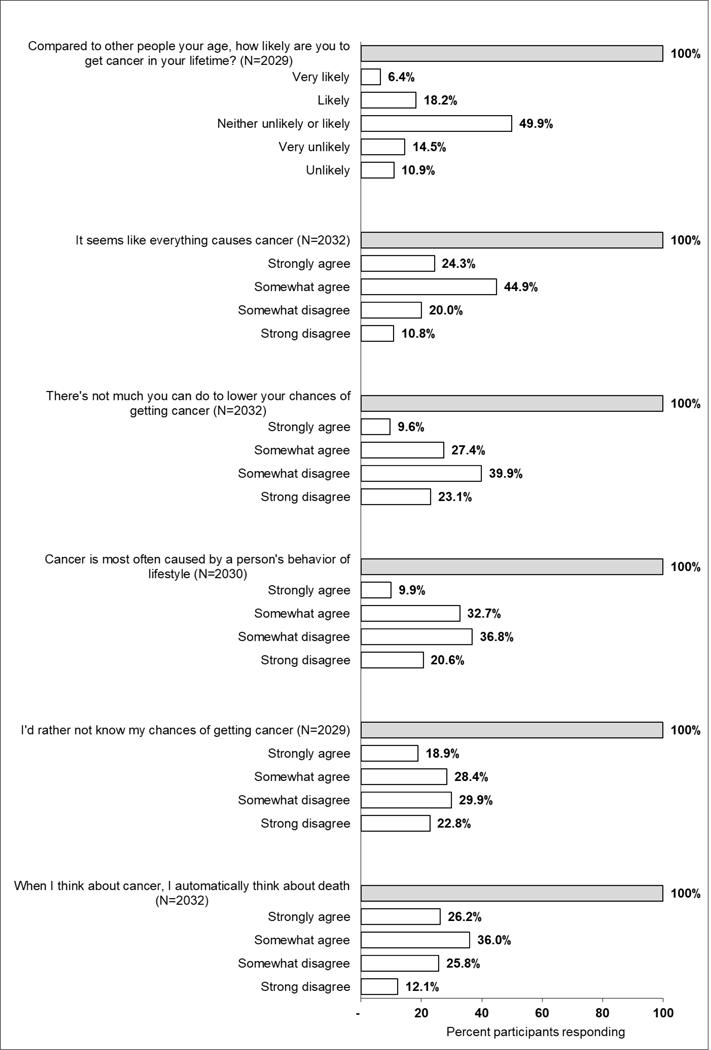

Almost half of respondents (49.9%) perceived their risk of cancer as similar to others of the same age, while the remaining were almost equally split between considering themselves at increased (24.6%) or decreased (25.4%) risk (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perceived risk of and beliefs about cancer. Percentage frequency distribution of participants responding to each of the cancer-related risk and belief questions.

Five questions assessed beliefs about cancer. A high proportion of respondents agreed that “it seems like everything causes cancer” (69.2%), “when I think about cancer, I automatically think about death” (62.2%), and “I’d rather not know my chance of getting cancer” (47.3%). A substantial number also agreed that “there’s not much that you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer” (37%). The majority disagreed with the belief that “cancer is most often caused by a person’s behavior or lifestyle” (57.4%).

Regression analyses

We conducted multivariable weighted survey logistic regression and BFDP analyses to identify noteworthy associations with outcomes of perceived risk of cancer and cancer beliefs. Table 3 presents the predictors tested, including demographics, key behaviors, and health-related factors.

Table 3.

Multivariable regression analyses of cancer beliefs

| Predictors | Compared to other people your age, how likely are you to get cancer in your lifetime? |

HOW MUCH DO YOU AGREE OR DISAGREE WITH THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS:b |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It seems like everything causes cancer |

There’s not much you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer |

Cancer is most often caused by a person’s behavior or lifestyle |

I’d rather not know my chance of getting cancer |

When I think about cancer, I automatically think about death |

||||||||||||||||||||

| ORa | 95% CI | P -Value | BFDP | OR | 95% CI | P -Value | BFDP | OR | 95% CI | P -Value | BFDP | OR | 95% CI | P -Value | BFDP | OR | 95% CI | P -Value | BFDP | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | BFDP | |

| SEX | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male vs female | 0.74 | 0.53–1.03 | 0.071 | 0.939 | 0.80 | 0.63–1.02 | 0.068 | 0.949 | 1.00 | 0.80–1.26 | 0.982 | 0.989 | 1.58 | 1.26–1.97 | <0.001 | 0.033 | 1.13 | 0.91–1.41 | 0.276 | 0.982 | 1.02 | 0.81–1.28 | 0.873 | 0.989 |

| AGE (ref. 18–36 years) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37–64 years | 1.52 | 1.02–2.27 | 0.041 | 0.897 | 1.32 | 0.99–1.77 | 0.063 | 0.937 | 0.74 | 0.57–0.97 | 0.030 | 0.894 | 1.07 | 0.82–1.39 | 0.633 | 0.986 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.04 | 0.095 | 0.956 | 1.15 | 0.88–1.51 | 0.305 | 0.980 |

| 65 years and older | 1.00 | 0.46–2.15 | 0.990 | 0.971 | 0.91 | 0.51–1.62 | 0.747 | 0.975 | 0.66 | 0.37–1.18 | 0.158 | 0.950 | 1.08 | 0.63–1.83 | 0.789 | 0.977 | 0.44 | 0.25–0.77 | 0.004 | 0.611 | 1.10 | 0.64–1.91 | 0.724 | 0.976 |

| Race (ref. NHW) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NHB | 0.53 | 0.34–0.81 | 0.004 | 0.555 | 0.98 | 0.71–1.35 | 0.910 | 0.985 | 1.08 | 0.80–1.46 | 0.634 | 0.985 | 0.80 | 0.59–1.07 | 0.130 | 0.963 | 1.00 | 0.74–1.34 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 1.14 | 0.85–1.52 | 0.400 | 0.981 |

| Hispanic | 0.91 | 0.61–1.35 | 0.630 | 0.981 | 1.24 | 0.93–1.65 | 0.142 | 0.965 | 1.32 | 1.01–1.72 | 0.043 | 0.917 | 0.82 | 0.63–1.07 | 0.143 | 0.967 | 1.07 | 0.83–1.38 | 0.600 | 0.987 | 1.50 | 1.14–1.96 | 0.004 | 0.555 |

| Other race | 0.94 | 0.50–1.77 | 0.846 | 0.974 | 1.31 | 0.85–2.00 | 0.220 | 0.964 | 1.19 | 0.78–1.81 | 0.430 | 0.976 | 1.12 | 0.75–1.68 | 0.580 | 0.980 | 1.09 | 0.73–1.62 | 0.691 | 0.981 | 1.13 | 0.75–1.70 | 0.569 | 0.979 |

| Born in US | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No vs yes | 0.47 | 0.26–0.83 | 0.010 | 0.741 | 0.61 | 0.42–0.88 | 0.009 | 0.721 | 0.97 | 0.66–1.42 | 0.876 | 0.983 | 1.24 | 0.85–1.81 | 0.257 | 0.971 | 0.97 | 0.68–1.40 | 0.877 | 0.983 | 1.15 | 0.77–1.69 | 0.498 | 0.979 |

|

Education (ref. 12 years/completed high school) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 1.00 | 0.48–2.05 | 0.989 | 0.972 | 1.35 | 0.79–2.33 | 0.274 | 0.964 | 1.27 | 0.78–2.06 | 0.342 | 0.970 | 1.03 | 0.62–1.72 | 0.900 | 0.978 | 0.82 | 0.51–1.33 | 0.427 | 0.973 | 0.91 | 0.55–1.52 | 0.726 | 0.977 |

| Post High School/some college | 1.07 | 0.70–1.63 | 0.748 | 0.981 | 1.15 | 0.85–1.57 | 0.364 | 0.980 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.08 | 0.150 | 0.966 | 1.09 | 0.82–1.45 | 0.574 | 0.985 | 0.74 | 0.56–0.98 | 0.036 | 0.906 | 0.91 | 0.68–1.21 | 0.496 | 0.984 |

|

College graduate/postgraduate |

1.08 | 0.68–1.69 | 0.753 | 0.980 | 0.80 | 0.58–1.12 | 0.194 | 0.968 | 0.68 | 0.50–0.93 | 0.016 | 0.824 | 1.34 | 0.98–1.83 | 0.065 | 0.936 | 0.73 | 0.54–0.98 | 0.038 | 0.905 | 0.84 | 0.62–1.15 | 0.277 | 0.976 |

| Marital Status (ref. married/living as married) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Divorced/separated | 0.50 | 0.29–0.86 | 0.012 | 0.775 | 0.92 | 0.63–1.33 | 0.650 | 0.982 | 0.98 | 0.68–1.40 | 0.901 | 0.984 | 0.88 | 0.62–1.25 | 0.468 | 0.980 | 1.00 | 0.71–1.42 | 0.980 | 0.984 | 0.84 | 0.59–1.19 | 0.314 | 0.976 |

| Single/never been married | 1.13 | 0.75–1.69 | 0.566 | 0.979 | 1.00 | 0.75–1.34 | 0.996 | 0.987 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.08 | 0.147 | 0.966 | 1.01 | 0.77–1.33 | 0.930 | 0.987 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.20 | 0.502 | 0.984 | 1.09 | 0.82–1.46 | 0.539 | 0.984 |

| Widowed | 0.46 | 0.18–1.21 | 0.115 | 0.935 | 0.92 | 0.49–1.71 | 0.782 | 0.974 | 0.80 | 0.43–1.50 | 0.491 | 0.970 | 0.65 | 0.36–1.18 | 0.155 | 0.948 | 1.00 | 0.56–1.77 | 0.995 | 0.976 | 1.32 | 0.71–2.43 | 0.380 | 0.967 |

| Total Household | 0.99 | 0.91–1.08 | 0.844 | 0.996 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.05 | 0.603 | 0.996 | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 0.130 | 0.988 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.05 | 0.536 | 0.996 | 1.01 | 0.95–1.06 | 0.790 | 0.997 | 1.08 | 1.01–1.16 | 0.035 | 0.970 |

| Employment Status (ref. Employed) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disabled | 1.29 | 0.59–2.83 | 0.520 | 0.966 | 0.63 | 0.38–1.06 | 0.082 | 0.928 | 0.95 | 0.59–1.53 | 0.825 | 0.979 | 0.75 | 0.46–1.22 | 0.250 | 0.964 | 0.74 | 0.45–1.20 | 0.215 | 0.962 | 0.87 | 0.54–1.41 | 0.576 | 0.976 |

| Homemaker | 1.07 | 0.62–1.86 | 0.801 | 0.976 | 1.25 | 0.84–1.84 | 0.267 | 0.970 | 1.01 | 0.70–1.45 | 0.956 | 0.984 | 0.94 | 0.65–1.36 | 0.751 | 0.983 | 1.19 | 0.84–1.70 | 0.323 | 0.976 | 0.93 | 0.65–1.35 | 0.709 | 0.982 |

| Retired | 1.28 | 0.37–4.44 | 0.697 | 0.961 | 0.55 | 0.25–1.18 | 0.125 | 0.938 | 0.99 | 0.48–2.03 | 0.973 | 0.972 | 1.55 | 0.76–3.16 | 0.226 | 0.954 | 1.34 | 0.71–2.52 | 0.363 | 0.965 | 0.58 | 0.30–1.15 | 0.119 | 0.937 |

| Student | 1.34 | 0.68–2.64 | 0.391 | 0.965 | 0.85 | 0.52–1.38 | 0.502 | 0.975 | 1.01 | 0.61–1.66 | 0.975 | 0.979 | 0.96 | 0.61–1.50 | 0.842 | 0.980 | 1.23 | 0.76–1.97 | 0.400 | 0.972 | 0.80 | 0.50–1.28 | 0.351 | 0.971 |

| Unemployed | 0.85 | 0.43–1.66 | 0.635 | 0.971 | 0.89 | 0.56–1.44 | 0.645 | 0.977 | 0.83 | 0.53–1.29 | 0.398 | 0.974 | 1.34 | 0.84–2.12 | 0.217 | 0.962 | 1.53 | 0.96–2.43 | 0.071 | 0.925 | 1.22 | 0.76–1.95 | 0.416 | 0.973 |

| Other | 0.99 | 0.59–1.65 | 0.959 | 0.978 | 0.77 | 0.52–1.15 | 0.200 | 0.964 | 0.69 | 0.47–1.01 | 0.054 | 0.919 | 0.94 | 0.64–1.37 | 0.730 | 0.982 | 0.81 | 0.56–1.18 | 0.277 | 0.972 | 0.86 | 0.58–1.26 | 0.425 | 0.978 |

| Income (ref. $50,000 - $74,999) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <$20,000 | 0.71 | 0.42–1.22 | 0.220 | 0.959 | 0.61 | 0.42–0.89 | 0.010 | 0.755 | 1.12 | 0.77–1.62 | 0.551 | 0.981 | 0.96 | 0.67–1.37 | 0.808 | 0.984 | 1.29 | 0.91–1.82 | 0.160 | 0.961 | 0.95 | 0.66–1.37 | 0.774 | 0.983 |

| $20,000 - $49,999 | 1.07 | 0.69–1.67 | 0.760 | 0.980 | 0.83 | 0.60–1.15 | 0.267 | 0.974 | 0.97 | 0.71–1.33 | 0.856 | 0.985 | 1.07 | 0.79–1.44 | 0.665 | 0.985 | 1.26 | 0.94–1.69 | 0.122 | 0.960 | 1.09 | 0.80–1.48 | 0.596 | 0.984 |

| $75,000 - $99,999 | 0.82 | 0.46–1.44 | 0.488 | 0.972 | 1.08 | 0.69–1.68 | 0.740 | 0.980 | 1.29 | 0.87–1.91 | 0.198 | 0.965 | 1.01 | 0.69–1.48 | 0.961 | 0.983 | 1.37 | 0.93–2.01 | 0.113 | 0.948 | 1.19 | 0.80–1.78 | 0.397 | 0.976 |

| ≥$100,000 | 0.77 | 0.43–1.36 | 0.359 | 0.968 | 0.82 | 0.54–1.24 | 0.339 | 0.973 | 0.75 | 0.50–1.12 | 0.157 | 0.959 | 0.79 | 0.54–1.17 | 0.236 | 0.968 | 0.91 | 0.62–1.33 | 0.617 | 0.981 | 1.25 | 0.84–1.85 | 0.268 | 0.970 |

| Home Ownership (ref. own) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupied | 1.22 | 0.67–2.23 | 0.519 | 0.971 | 0.76 | 0.50–1.17 | 0.219 | 0.964 | 0.93 | 0.62–1.39 | 0.707 | 0.981 | 0.87 | 0.58–1.32 | 0.517 | 0.978 | 1.03 | 0.69–1.53 | 0.902 | 0.982 | 0.79 | 0.53–1.17 | 0.237 | 0.968 |

| Rent | 1.13 | 0.79–1.63 | 0.505 | 0.980 | 0.80 | 0.61–1.05 | 0.106 | 0.959 | 0.99 | 0.77–1.27 | 0.928 | 0.988 | 1.21 | 0.95–1.56 | 0.127 | 0.968 | 0.91 | 0.71–1.17 | 0.456 | 0.985 | 0.90 | 0.70–1.17 | 0.426 | 0.984 |

| BMI (ref. normal weight) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 0.66 | 0.25–1.80 | 0.419 | 0.959 | 0.78 | 0.41–1.49 | 0.457 | 0.968 | 1.05 | 0.55–2.02 | 0.887 | 0.974 | 1.14 | 0.62–2.08 | 0.675 | 0.974 | 1.08 | 0.58–2.00 | 0.805 | 0.974 | 0.84 | 0.47–1.53 | 0.574 | 0.972 |

| Overweight | 1.14 | 0.75–1.72 | 0.548 | 0.979 | 1.37 | 1.02–1.85 | 0.038 | 0.910 | 1.04 | 0.78–1.39 | 0.793 | 0.986 | 0.90 | 0.68–1.20 | 0.470 | 0.983 | 0.98 | 0.74–1.30 | 0.900 | 0.987 | 1.25 | 0.94–1.67 | 0.128 | 0.963 |

| Class I Obesity | 1.38 | 0.86–2.21 | 0.184 | 0.958 | 1.25 | 0.90–1.75 | 0.187 | 0.968 | 0.98 | 0.71–1.36 | 0.923 | 0.985 | 0.85 | 0.62–1.17 | 0.322 | 0.977 | 0.98 | 0.72–1.34 | 0.900 | 0.986 | 0.86 | 0.63–1.17 | 0.331 | 0.979 |

| Class II Obesity | 1.36 | 0.74–2.49 | 0.318 | 0.964 | 1.20 | 0.79–1.83 | 0.391 | 0.975 | 1.38 | 0.93–2.04 | 0.110 | 0.947 | 1.16 | 0.78–1.73 | 0.454 | 0.978 | 1.19 | 0.81–1.76 | 0.381 | 0.976 | 1.29 | 0.87–1.93 | 0.204 | 0.966 |

| Class III Obesity | 2.29 | 1.28–4.12 | 0.006 | 0.673 | 1.99 | 1.30–3.04 | 0.002 | 0.391 | 1.25 | 0.84–1.85 | 0.268 | 0.970 | 1.19 | 0.81–1.74 | 0.381 | 0.976 | 0.95 | 0.65–1.39 | 0.786 | 0.983 | 1.51 | 1.00–2.29 | 0.049 | 0.912 |

| Smoking Status (ref. never) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current | 2.06 | 1.37–3.12 | 0.001 | 0.248 | 1.59 | 1.16–2.16 | 0.004 | 0.544 | 1.37 | 1.03–1.81 | 0.030 | 0.885 | 1.16 | 0.88–1.53 | 0.305 | 0.979 | 1.67 | 1.26–2.21 | <0.001 | 0.154 | 1.09 | 0.82–1.45 | 0.554 | 0.985 |

| Former | 2.04 | 1.27–3.26 | 0.003 | 0.530 | 1.45 | 1.03–2.03 | 0.033 | 0.884 | 0.95 | 0.69–1.30 | 0.734 | 0.985 | 1.07 | 0.79–1.46 | 0.652 | 0.985 | 1.21 | 0.89–1.63 | 0.225 | 0.972 | 1.38 | 1.01–1.90 | 0.046 | 0.919 |

| Diabetes (ref. no) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borderline | 1.07 | 0.58–1.98 | 0.820 | 0.974 | 0.83 | 0.54–1.28 | 0.396 | 0.974 | 1.03 | 0.69–1.55 | 0.880 | 0.982 | 1.04 | 0.70–1.55 | 0.834 | 0.982 | 0.99 | 0.67–1.46 | 0.963 | 0.983 | 1.48 | 0.94–2.33 | 0.092 | 0.936 |

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.56–1.47 | 0.702 | 0.978 | 1.12 | 0.77–1.62 | 0.555 | 0.981 | 1.33 | 0.94–1.89 | 0.103 | 0.952 | 1.07 | 0.76–1.49 | 0.714 | 0.984 | 1.18 | 0.85–1.66 | 0.324 | 0.977 | 1.11 | 0.79–1.58 | 0.540 | 0.982 |

| Depression (ref. never) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Few times per year | 1.79 | 1.17–2.74 | 0.008 | 0.698 | 1.29 | 0.97–1.71 | 0.086 | 0.946 | 0.95 | 0.72–1.27 | 0.745 | 0.986 | 0.80 | 0.61–1.05 | 0.111 | 0.959 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.06 | 0.119 | 0.963 | 1.46 | 1.11–1.92 | 0.006 | 0.713 |

| Daily/monthly/weekly | 2.92 | 1.95–4.39 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.67 | 1.26–2.22 | <0.001 | 0.180 | 1.44 | 1.09–1.89 | 0.010 | 0.753 | 0.90 | 0.69–1.18 | 0.459 | 0.984 | 1.20 | 0.92–1.57 | 0.171 | 0.972 | 2.05 | 1.56–2.69 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

OR: (very likely + likely) versus (unlikely + very unlikely)

OR: (strongly agree + somewhat agree) versus (somewhat disagree + strongly disagree)

Abbreviations: BFDP, Bayesian false-discovery probabilities; BMI, body mass index.

Factors associated with the question “compared to other people your age, how likely are you to get cancer in your lifetime,” included smoking status, BMI, depression, race, place of birth and marital status. Respondents with perceptions of higher cancer risk included: current and former smokers versus never smokers (OR, 2.06; P = 0.001; BFDP, 0.248 and OR, 2.04; P = 0.003; BFDP = 0.530, respectively); those with class III obesity versus normal weight (OR, 2.29; P = 0.006; BFDP = 0.673); and those with frequent and infrequent depression versus no depression (OR, 2.92; P < 0.001; BFDP < 0.001 and OR, 1.79; P = 0.008; BFDP = 0.698, respectively). Respondents with perceptions of lower cancer risk included: NHB versus NHW race (OR, 0.53; P = 0.004; BFDP = 0.555); those born outside versus within the US (OR, 0.47; P = 0.010; BFDP = 0.741); and divorced/separated versus married/living as married (OR, 0.50; P = 0.012; BFDP = 0.775).

Factors associated with the belief that “it seems like everything causes cancer” included depression, smoking status, BMI, place of birth, and household income. Respondents were more likely to agree with this belief if they had frequent versus no depression (OR, 1.67; P <0.001; BFDP = 0.180); class III obesity versus normal weight (OR, 1.99; P = 0.002; BFDP = 0.391); or were current versus never smokers (OR, 1.59; P = 0.004; BFDP = 0.544). Respondents were less likely to agree with this belief if they were born outside versus within the US (OR, 0.61; P = 0.009; BFDP = 0.721) and if they had an annual household income less than $20,000 versus $50,000-$74,999 (OR, 0.61; P = 0.010; BFDP = 0.755).

The only factor associated with the belief, “there’s not much you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer,” was depression; respondents were more likely to agree if they reported frequent versus no depression (OR, 1.44; P = 0.010; BFDP = 0.753).

The only factor associated with the belief, “cancer is most often caused by a person’s behavior or lifestyle,” was sex; respondents were more likely to agree if they were male versus female (OR, 1.58; P < 0.001; BFDP = 0.033).

Factors associated with the belief, “I’d rather not know my chance of getting cancer,” were smoking and age. Respondents were more likely to agree with this belief if they were current versus never smokers (OR, 1.67; P <0.001; BFDP = 0.154) and more likely to disagree if they were at least 65 years old versus 18–36 years (OR, 0.44; P = 0.004; BFDP = 0.611).

Factors associated with the belief, “when I think about cancer, I automatically think about death,” included ethnicity and depression. Respondents were more likely to agree if they were of Hispanic versus non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.50; P = 0.004; BFDP = 0.555) and if they reported frequent and infrequent depression versus no depression (OR, 2.05; P < 0.001; BFDP < 0.001 and OR, 1.46; P = 0.006; BFDP = 0.713, respectively).

Discussion

This study sought to uncover key factors influencing cancer beliefs and perceptions of cancer risk among Texas residents to provide a deeper understanding of issues pertaining to cancer prevention and control across the state. Our principal findings include not wanting to know personal cancer risk, lack of knowledge about the impact of lifestyle choices on cancer risk, and pessimism about cancer prevention among a high percentage of Texas residents. Notably, self-reported frequent depression emerged as a key factor associated with fatalistic beliefs about cancer as well as perceptions of increased cancer risk.

Excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, 39.7% of men and 37.7% of women will develop an invasive malignancy during their lifetime (33). Despite these statistics, about one quarter of Texas respondents believed they were unlikely/very unlikely to develop cancer compared with others of the same age. These data are consistent with earlier studies that find the general population tends to be optimistic about their personal health and cancer risks (34,35). Lower perceived risk was particularly apparent among NHBs versus NHWs and those born outside the US, of which the majority were Hispanics followed by NHBs and Asians. Such a perception among minority populations has previously been attributed, at least in part, to decreased awareness of family cancer history and its relevance to personal cancer risk, as well as cultural and community-level differences regarding salient information on cancer risk and knowledge and openness about the disease (36). Optimistic health tendencies has been associated with reduced uptake of preventive measures, and this belief may help explain the substantial cancer disparities that persist among NHBs and Hispanics in Texas (2,37,38).

Unrealistic optimism about health outcomes is prevalent among the general population and has also been observed among individuals with increased health burden, including smokers (7,39). This optimism was not apparent among several high-risk groups in our study, including current and former smokers and those with class III obesity or self-reported depression; all these groups expressed increased cancer risk. One possible explanation is that the topic of our survey attracted a greater proportion of high-risk respondents who were more informed about cancer in general. Nonetheless, our data are encouraging in light of published work showing that smokers who are more realistic about their cancer risk have more interest in quitting (39). Also, our data imply that health messaging about obesity is starting to reach those most at risk for development of obesity-related disease in Texas. That obese individuals are becoming more aware of their health risks is supported by HINTs data showing that individuals with a BMI of 30 or greater were more likely to have perceptions of increased cancer risk compared with individuals with normal weight (40).

It is alarming that the majority of our study sample was more likely to disagree that cancer risk is most often caused by a person’s behavior or lifestyle. Yet, this observation aligns with national data showing that, other than tobacco and excessive sun exposure, Americans are less likely to recognize lifestyle and more likely to identify cancer-causing factors that are beyond their control, such as cancer genes and the environment (13). Texas respondents with high or low health burdens were equally uninformed about the impact of behavior and lifestyle on cancer risk. This is unfortunate, as evaluation of large national cohorts has shown a substantial difference in cancer incidence and mortality between individuals following healthy versus unhealthy lifestyles (41). Respondents reporting depression were also less likely to believe that cancer could be prevented with lifestyle modification. This is important because past-year depression is common among smokers, and depression is associated with alcohol use disorders (42,43). Interestingly, receiving cancer-related information primarily through health care professionals has been demonstrated to increase awareness of behavioral risks (44). Unfortunately, Texas has one of the lowest health insurance rates in the nation and a dearth of primary care providers (45). These deficiencies may exacerbate prevention efforts in the state.

Recognizing differences in data collection, we found that the preference to avoid cancer risk information was higher in Texas respondents compared with national data (17). That nearly half of our study sample would rather not know their personal risk of cancer is troubling because such behavior has been associated with lower intent to engage in or complete cancer screening (17,46). However, we found that respondents 65 years and older preferred to know their risk. This finding may reflect increased self-efficacy among older individuals recruited to online surveys. Notably, not wanting know one’s chance of getting cancer was apparent in the particularly vulnerable population of current smokers in Texas. This behavior may be motivated by low self-efficacy to quit or by attempts to limit anxiety and maintain hope (15). Such behavior also allows smokers to override guilt and continue with their preferred lifestyle choice. These actions are consistent with smokers’ placing less value on early detection and being less likely to consider undergoing lung cancer screening by computed tomography (47,48).

Fatalistic beliefs about cancer and its prevention have been associated not only with decreased rates of screening but also with reduced commitment to healthy behaviors (9,49). Our study measured fatalistic beliefs by assessing respondents’ association of death with cancer, belief that everything causes cancer, and agreement that little could be done to lower one’s cancer risk. Automatic association of death with cancer was more common than not in our study sample, matching the high rates previously reported for the US population as a whole (22). This belief was more prevalent among Hispanics in our study, supporting prior studies showing dominance of cancer fatalism among this ethnic group (49). Future analysis could examine whether levels of health insurance in this group is associated with fatalistic beliefs as lack of coverage would be expected to influence ability to seek care.

Pessimism about cancer prevention, as measured by the notion that “it seems like everything causes cancer,” was also prevalent and exceeded 2003 national estimates (9). Class III obesity and current smoking was positively associated with this belief, a finding that is in line with prior evidence linking fatalism to uptake of health-adverse behaviors and lower engagement in cancer prevention strategies (9). That smokers tend to endorse such has previously been correlated with their tendency to endorse self-exempting beliefs (44).

Compared with national 2003 data, our study sample was about 10% more inclined to believe that little could be done to lower one’s chances of getting cancer (9). This finding highlights a need for new strategies to better educate and empower the Texas population on approaches to cancer prevention. That self-reported depression was positively associated with all three fatalistic beliefs about cancer is consistent with the higher rates of depression reported among those believing external factors govern life events (50).

A recurring theme in this study was that respondents who reported frequent depression had higher perceptions of cancer risk and a greater tendency to endorse fatalistic beliefs about cancer. We are not aware of any other study highlighting the importance of depression as a prominent factor across cancer beliefs and perceptions. However, depressive symptoms and increased trait anxiety have been linked to the belief that cancer is incurable, and this belief can lead to delays in seeking treatment (51). Mental illness, including clinical depression, has also been associated with lower rates of screening mammography (52). This may be related in part to decreased self-efficacy. Thus, interventions aimed at reducing depressive symptomatology might have a favorable impact not only on perceptions of cancer risk and engagement in risk-reducing behaviors, but also on uptake of cancer screening. Primary care physicians should be cognizant of these ramifications. In the future, it will be important to evaluate cancer risk perceptions and beliefs among individuals completing validated instruments for depression and among those with a clinical diagnosis.

Limitations

In this study, sampling was among online research panelists; therefore, future validation using independent data collected using other sampling methods is required. Our study population trended toward higher educational attainment compared with Texas as a whole, and this trend may reflect the electronic mode of survey administration. There was also some skewing toward lower income ranges compared with state data, and thus conclusions drawn may be less reliable for those at the higher end of the socioeconomic ladder. The proportion of individuals responding to the Spanish language survey was low, suggesting that Qualtrics panels tend to capture more acculturated Hispanics. However, the weighting strategy used in our analyses ensured valid statistical inference representing Texas by sex, age, ethnicity, and race strata.

The nonprobability sampling design may have enriched our sample for respondents who have special interest in cancer prevention. Also, depression was assessed using single self-reported measure. Thus, individuals were not clinically diagnosed, and it is possible that depression was also selected by respondents with anxiety and stress.

Of note, some of the subgroup associations are borderline significant, and these instances may represent false positives due to small sample size. Moreover, some of the associations found may not be statistically significant if adjusted for multiple comparisons. To control the false-discovery rate, we calculated BFDP to evaluate the noteworthiness of observed associations. Finally, because the survey was a cross-sectional design, it is not possible to infer causality.

In summary, we found that not wanting to know personal cancer risk and low confidence in cancer beliefs was prevalent across Texas. There was also a lack of knowledge regarding the impact of personal lifestyle choices. We identified several key racial and ethnic differences regarding cancer beliefs, and this finding will help target and inform future cancer prevention research in the state. That self-reported perceptions of depression emerged as a recurring theme in fatalistic beliefs about cancer provides the groundwork for more dedicated research in this area.

Acknowledgements

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute through Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) 5P30CA016672, CCSG subproject 5697 (PI: S Shete), and the Assessment, Intervention, and Measurement (AIM) Shared Resource through 5P30CA016672 and the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment; and The Barnhart Family Distinguished Professorship in Targeted Therapy. The authors would like to thank: Elenita Tamez and George Baum from MD Anderson’s Assessment, Intervention, and Measurement (AIM) Shared Resources for their support with the Qualtrics platform; George Baum for conducting preliminary analyses; Henry Gomez from the Department of Epidemiology for help with Spanish translation; Lizzet Aguillon, Joanna Garcia, Loisann Guerra, and Eleazar Montes Jr, from the Department of Epidemiology, for reviewing and piloting of the Spanish language survey; Mehwish Javaid and Diane Benson, from the Office of Health Policy, for input during questionnaire development and prelaunch survey testing; Bryan Tutt, from the Department of Scientific Publications, for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Expected Cancer Cases and Deaths. Texas Department of State Health Services. Available at: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/tcr/data/expected-cases-and-deaths.aspx Accessed on: July 31, 2018.

- 2.State Cancer Profiles. National Cancer Institute, Available at: http://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/index.html Accessed on: July 31, 2018.

- 3.An Economic Assessment of the Cost of Cancer in Texas An Economic Assessment of the Cost of Cancer in Texas Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) and its Programs: 2017 Update Available at: http://www.cprit.state.tx.us/images/uploads/perryman_cprit_impact_2017.pdf Accessed on: July 31, 2018.

- 4.Wu S, Powers S, Zhu W, Hannun YA. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature 2016;529(7584):43–7 doi 10.1038/nature16166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Census Bureau. American Fact Finder. Texas. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml Accessed on: July 3, 2018.

- 6.Cancer in Texas, 2017. Department of State Health Services. Available at: http://www.dshs.texas.gov/Legislative/Reports-2017.aspx Accessed on: July 15, 2018.

- 7.Ferrer R, Klein WM. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr Opin Psychol 2015;5:85–9 doi 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez AS, Rutten LJ, Oh A, Vengoechea BL, Moser RP, Vanderpool RC, et al. Perceptions of cancer controllability and cancer risk knowledge: the moderating role of race, ethnicity, and acculturation. J Cancer Educ 2013;28(2):254–61 doi 10.1007/s13187-013-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niederdeppe J, Levy AG. Fatalistic beliefs about cancer prevention and three prevention behaviors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16(5):998–1003 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan HW, Rutten LJ, Hesse BW, Moser RP, Rothman AJ, McCaul KD. Lay representations of cancer prevention and early detection: associations with prevention behaviors. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7(1):A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colditz GA, Peterson LL. Obesity and Cancer: Evidence, Impact, and Future Directions. Clin Chem 2018;64(1):154–62 doi 10.1373/clinchem.2017.277376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M, Comparative Risk Assessment collaborating g. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet 2005;366(9499):1784–93 doi 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AICR 2015 Cancer Risk Awareness Survey Report. Available at: http://www.aicr.org/assets/docs/pdf/education/aicr-awareness-report-2015.pdf Accessed on: September 17, 2018.

- 14.More than 4 in 10 Cancers and Cancer Deaths Linked to Modifiable Risk Factors. American Cancer Society; Available at: https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/more-than-4-in-10-cancers-and-cancer-deaths-linked-to-modifiable-risk-factors.html Accessed on: December 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbour JB, Rintamaki LS, Ramsey JA, Brashers DE. Avoiding health information. J Health Commun 2012;17(2):212–29 doi 10.1080/10810730.2011.585691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell JL, Crosier BS, Shepperd JA. Does lacking threat-management resources increase information avoidance? A multi-sample, multi-method investigation. Journal of Research in Personality 2014;50:102–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emanuel AS, Kiviniemi MT, Howell JL, Hay JL, Waters EA, Orom H, et al. Avoiding cancer risk information. Soc Sci Med 2015;147:113–20 doi 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:399–418 doi 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev 2015;9(3):323–44 doi 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powe BD, Finnie R. Cancer fatalism: the state of the science. Cancer Nurs 2003;26(6):454–65; quiz 66–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleary SA, Paasche-Orlow MK, Joseph P, Freund KM. The Relationship Between Health Literacy, Cancer Prevention Beliefs, and Cancer Prevention Behaviors. J Cancer Educ 2018. doi 10.1007/s13187-018-1400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moser RP, Arndt J, Han PK, Waters EA, Amsellem M, Hesse BW. Perceptions of cancer as a death sentence: prevalence and consequences. J Health Psychol 2014;19(12):1518–24 doi 10.1177/1359105313494924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell JA, Manning M, Shires D, Chapman RA, Burnett J. Fatalistic Beliefs About Cancer Prevention Among Older African American Men. Res Aging 2015;37(6):606–22 doi 10.1177/0164027514546697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Household Income in Texas. Statistical Atlas. Available at: https://statisticalatlas.com/state/Texas/Household-Income Accessed on: February 13.

- 25.Definitions of County Designations. Texas Health and Human Services; Available at: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/chs/hprc/counties.shtm Accessed on: February 13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Texas ZIP Codes. Available at: https://www.zip-codes.com/state/tx.asp accessed on: February 13.

- 27.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire (BRFSS), 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2016_BRFSS_Questionnaire_FINAL.pdf Accessed on: July 14, 2018.

- 28.National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm Accessed on: July 14, 2018.

- 29.Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Available at: https://hints.cancer.gov/data/survey-instruments.aspx Accessed on: July 14, 2018.

- 30.Body mass index - BMI. World Health Organization; Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi Accessed on: December 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercer A, Lau A, Kennedy C. Pew Research Center. For Weighting Online Opt-In Samples, What Matters Most? Available at: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2018/01/26170902/Weighting-Online-Opt-In-Samples.pdf Accessed on: July 23, 2018 2018.

- 32.Wakefield J A Bayesian measure of the probability of false discovery in genetic epidemiology studies. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81(2):208–27 doi 10.1086/519024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lifetime Risk of Developing or Dying From Cancer. American Cancer Society; Avaialble at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/lifetime-probability-of-developing-or-dying-from-cancer.html Accessed on: December 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontaine KR, Smith S. Optimistic bias in cancer risk perception: a cross-national study. Psychol Rep 1995;77(1):143–6 doi 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke VA, Lovegrove H, Williams A, Machperson M. Unrealistic optimism and the Health Belief Model. J Behav Med 2000;23(4):367–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orom H, Kiviniemi MT, Underwood W 3rd, Ross L, Shavers VL Perceived cancer risk: why is it lower among nonwhites than whites? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19(3):746–54 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Alcaraz KI, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66(4):290–308 doi 10.3322/caac.21340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Islami F, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Ward EM, Jemal A. Disparities in liver cancer occurrence in the United States by race/ethnicity and state. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67(4):273–89 doi 10.3322/caac.21402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dillard AJ, McCaul KD, Klein WM. Unrealistic optimism in smokers: implications for smoking myth endorsement and self-protective motivation. J Health Commun 2006;11 Suppl 1:93–102 doi 10.1080/10810730600637343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverman KR, Ohman-Strickland PA, Christian AH. Perceptions of Cancer Risk: Differences by Weight Status. J Cancer Educ 2017;32(2):357–63 doi 10.1007/s13187-015-0942-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song M, Giovannucci E. Preventable Incidence and Mortality of Carcinoma Associated With Lifestyle Factors Among White Adults in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2016;2(9):1154–61 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinberger AH, Kashan RS, Shpigel DM, Esan H, Taha F, Lee CJ, et al. Depression and cigarette smoking behavior: A critical review of population-based studies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2017;43(4):416–31 doi 10.3109/00952990.2016.1171327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction 2011;106(5):906–14 doi 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peretti-Watel P, Fressard L, Bocquier A, Verger P. Perceptions of cancer risk factors and socioeconomic status. A French study. Prev Med Rep 2016;3:171–6 doi 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowers L, Gann C, Upton R. Small Area Health Insurance Estimates: 2016. Small Area Estimates. Current Population Reports Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sahie.html Accessed on: July 31, 2018 2018.

- 46.Shepperd JA, Howell JL, Logan H. A survey of barriers to screening for oral cancer among rural Black Americans. Psychooncology 2014;23(3):276–82 doi 10.1002/pon.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silvestri GA, Nietert PJ, Zoller J, Carter C, Bradford D. Attitudes towards screening for lung cancer among smokers and their non-smoking counterparts. Thorax 2007;62(2):126–30 doi 10.1136/thx.2005.056036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delmerico J, Hyland A, Celestino P, Reid M, Cummings KM. Patient willingness and barriers to receiving a CT scan for lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer 2014;84(3):307–9 doi 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Espinosa de Los Monteros K, Gallo LC. The relevance of fatalism in the study of Latinas’ cancer screening behavior: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Med 2011;18(4):310–8 doi 10.1007/s12529-010-9119-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benassi VA, Sweeney PD, Dufour CL. Is there a relation between locus of control orientation and depression? J Abnorm Psychol 1988;97(3):357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chojnacka-Szawlowska G, Koscielak R, Karasiewicz K, Majkowicz M, Kozaka J. Delays in seeking cancer diagnosis in relation to beliefs about the curability of cancer in patients with different disease locations. Psychol Health 2013;28(2):154–70 doi 10.1080/08870446.2012.700056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell AJ, Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, Pepereke S, Mugadza V, Stubbs B. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205(6):428–35 doi 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]